پرنامبوكو

State of Pernambuco | |

|---|---|

| النشيد: Hino de Pernambuco | |

Location of State of Pernambuco in Brazil | |

| الإحداثيات: 8°20′S 37°48′W / 8.333°S 37.800°W | |

| Country | |

| العاصمة وأكبر مدينة | رصيفي |

| الحكومة | |

| • حاكم | Paulo Câmara (PSB) |

| • نائب الحاكم | Luciana Santos (PCdoB) |

| • Senators | Fernando Bezerra Coelho (MDB) Humberto Costa (PT) Jarbas Vasconcelos (MDB) |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 98٬311٫616 كم² (37٬958٫327 ميل²) |

| ترتيب المساحة | 19th |

| التعداد (2012)[1] | |

| • الإجمالي | 8٬931٬028 |

| • الترتيب | 7th |

| • الكثافة | 91/km2 (240/sq mi) |

| • ترتيب الكثافة | 6th |

| صفة المواطن | Pernambucano/Pernambucana |

| GDP | |

| • Year | 2007 estimate |

| • Total | R$ 32,255,687,000 (10th) |

| • Per capita | R$ 4,337 (21st) |

| HDI | |

| • Year | 2017 |

| • Category | 0.727[2] – high (18th) |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC−03:00 (BRT) |

| Postal Code | 50000-000 to 56990-000 |

| ISO 3166 code | BR-PE |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | pe.gov.br |

پرنامبوكو Pernambuco واحدة من الولايات السبع والعشرين البرازيلية تقع في النصف الشرقي من الاقليم الشمالي الشرقي. With an estimated population of 9.6 million people as of 2020, it is the seventh-most populous state of Brazil, the sixth-most densely populated and the 19th-largest in area among federative units of the country. ويحدها بارايبا وسيارا من الشمال الغربي والمحيط الأطلسي من الشرق الاگواس وباهيا من الجنوب و بياوي من الغرب. وتضم جزيرة فرناندو دي نورونيا، وعاصمتها مدينة رصيفي، التي هي أحد أهم المراكز التجارية في البلد. Based on 2019 estimates, the Recife Metropolitan Region is seventh-most populous in the country, and the second-largest in northeastern Brazil.[3] In 2015, the state had 4.6% of the national population and produced 2.8% of the national gross domestic product (GDP).[4]

The contemporary state inherits its name from the Captaincy of Pernambuco, established in 1534. The region was originally inhabited by Tupi-Guarani-speaking peoples. European colonization began in the 16th century, under mostly Portuguese rule interrupted by a brief period of Dutch rule, followed by Brazilian independence in 1822. Large numbers of slaves were brought from Africa during the colonial era to cultivate sugarcane, and a significant portion of the state's population has some amount of African ancestry.

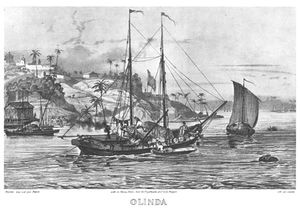

The state has rich cultural traditions thanks to its varied history and peoples. Brazilian Carnivals in Recife and the historic colonial capital of Olinda are renowned: the Galo da Madrugada parade in Recife has held world records for its size.

Historically a center of sugarcane cultivation due to the favorable climate, the state has a modern economy dominated by the services sector today, though large amounts of sugarcane are still grown. The coming of democracy in 1985 has brought the state progress and challenges in turn: while economic and health indicators have improved, inequality remains high.

الجغرافيا

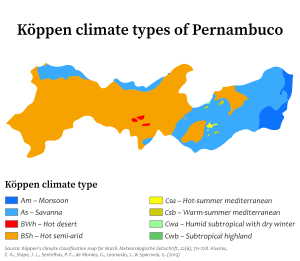

المناطق

The coastal area is fertile, and was formerly covered by the humid Pernambuco coastal forests, the northern extension of the Atlantic Forests (Mata Atlântica) of eastern Brazil. It is now occupied by extensive sugar cane plantations. It has a hot, humid climate, relieved to some extent by the south-east trade winds.[5]

The middle zone, called the agreste region, has a drier climate and lighter vegetation,[5] including the semi-deciduous Pernambuco interior forests, where many trees lose their leaves in the dry season.

الهيدرولوجيا

The rivers of the state include a number of small plateau streams flowing southward to the São Francisco River, and several large streams in the eastern part flowing eastward to the Atlantic. The former are the Moxotó, Ema, Pajeú, Terra Nova, Brigida, Boa Vista and Pontai, and are dry channels the greater part of the year.[5]

The largest of the coastal rivers are the Goiana River, which is formed by the confluence of the Tracunhaem and Capibaribe-mirim, and drains a rich agricultural region in the north-east part of the state; the Capibaribe, which has its source in the Serra de Jacarara and flows eastward to the Atlantic at Recife with a course of nearly 300 ميل (480 km); the Ipojuca, which rises in the Serra de Aldeia Velha and reaches the coast south of Recife; the Serinhaen; and the Uná. A large tributary of the Uná, the Rio Jacuhipe, forms part of the boundary line with Alagoas.[5]

التاريخ

قبل التاريخ

Prior to discovery and colonization by Portugal, Pernambuco was inhabited by numerous tribes of Tupi-Guarani speaking indigenous peoples. The Tupi peoples were a largely hunter-gatherer culture living in long houses who cultivated some indigenous crops, most notably manioc (Manihot esculenta), but lacked any metallic tools. Many elements of the Tupi culture were a shock to Europeans: among these, they bathed frequently, they eschewed wealth accumulation, practiced nudity, and warred frequently, primarily to capture enemies for communal, ritual cannibalism.[6]

الفتح الهولندي

In 1630, Pernambuco, as well as many Portuguese possessions in Brazil, was occupied by the Dutch until 1654.[5] The occupation was strongly resisted and the Dutch conquest was only partially successful, it was finally repelled by the Spaniards. In the interim, thousands of the enslaved Africans had fled to Palmares, and soon the mocambos there had grown into two significant states. The Dutch Republic, which allowed sugar production to remain in Portuguese hands, regarded suppression of Palmares as important, but was unsuccessful in this. Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen, count of Nassau, was appointed as ruler of the Nieuw Holland (Dutch colonization enterprise in Brazil).

In the 17th century, the Netherlands was experiencing a surge of freedom and progress, and wanted to expand their colonies in the American continent. An expression of this new economy was the Dutch West India Company, (modeled after the Dutch East India company which had influence throughout the world and controlled much of the trade between East and West). A Board of nineteen members appointed Prince Johan Maurits, Count of Nassau, Governor of Pernambuco. It was an auspicious choice for Northeast, because he was a lover of the arts with a deep interest in the New World. In 1637 he opened his government guidelines quite different from those of the Portuguese colonists, declaring "Freedom of Religion and Trade". His entourage contained traders, artists, planners, German and Dutch citizens. He was accompanied by six painters, including Frans Post and Albert Eckhout. Nassau also created an environment of Dutch religious tolerance, new to Portuguese America and irritating to his Calvinist associates. Nassau made efforts to reduce the sugar production monoculture by encouraging the cultivation of other crops, particularly foodstuffs.[7]

الهجرة اليهودية

Under Dutch rule, Jewish culture developed in Recife. Many Jews, having fled the Inquisition in Iberia, sought refuge in the Netherlands. The Jewish community established themselves in Dutch Brazil and would later migrate elsewhere in the Americas. There are records that in 1636 a synagogue was being built in the city. A Jewish scholar from Amsterdam, Isaac Aboab da Fonseca, arrived in Recife in 1642, becoming the first rabbi on Brazilian soil and on the continent. In 1643, three years after the Portuguese regained the crown in the metropolis, Father António Vieira – frowned upon, persecuted by the Inquisition and admirer of Aboab – recommended the King of Portugal occupy the capital of the New Christian and Jewish immigrants to help the depressed Portuguese finances[8]

عودة البرتغال

The Portuguese reconquered Recife in 1654 and Olinda regained its status of political center. However, Recife remained the commercial /port city. Nowadays, it is credited that many inhabitants of Pernambuco's agreste region have some Dutch ancestry.[9] If the Dutch were gone, however, the threat of the now unified quilombo of Palmares remained. In spite of a treaty negotiated in 1678 with its ruler Ganga Zumba, a war between the two remained. Zumbi who became ruler following the peace treaty and later repudiated it, fought the Portuguese government until 1694 when soldiers brought from the south eventually defeated him.

Three centuries of the sugar cycle

Throughout the remainder of the 17th century on to the 20th century much of life in Pernambuco was dominated by the patterns established by monoculture, latifundia, and slavery (until 1888). Sugar and cotton were grown on large plantations and rural society was largely divided into landowning elites and the impoverished poor. In addition, Pernambuco, except for a narrow coastland, is subject to periodic droughts. The boom and bust economy throughout this period is often exemplified as the "sugar cycle" when the international market for sugar is good, the economy booms, when the market is bad, it is hard times for all and particularly for the impoverished. Sugar has always been the principal example of the boom or bust cycle, but there has, from time to time been a similar cycle in cotton. Cotton was profitable during the U.S. War of Independence, the War of 1812, and the U.S. Civil War. Each time the bust in Pernambuco came when U.S. growers resumed their exports.[10]

17th-century class conflict

A sugar mill engenho requires a large investment both to build and to operate. Much of the time the money is borrowed. Although there were other sources, one source that was a particular irritant to mill owners were the merchants of Recife. In 1710 this irritant resulted in the Mascate War. This conflict set the mascates from Recife against the establishment planters of Olinda It was led by the Senhores de Engenho (owners of the sugar mills). It is an example of the continuing tensions between the senhores de engenho (the landed elites) in colonial Brazil and the merchants of Recife. The "War" (there was considerable shooting but little loss of life) has elements of class struggle. Olinda had, before the Dutch, always been the municipal seat. Recife, once merely a port facility for Olinda, had formerly consisted of a few modest dwellings, warehouses, and businesses catering to ships and seamen, but under the Dutch had been developed into a thriving center of commerce populated by wealthy, more recently arrived merchants to whom most of the landed aristocracy of Pernambuco were heavily indebted. After several excesses the king issued a new set of instructions to the governor. In 1715 the crown dispatched a new governor and the residents of Pernambuco finally felt the troubles were ended, though many families of the colony's elites were ruined.[11]

18th century: mining eclipses sugar

The discovery of gold in Minas Gerais late in the Seventeenth Century and the discovery of diamond displaced agriculture. In fact, for all the disruption caused by "gold fever" throughout the mining boom the value of sugar exports always exceeded the value of any other export.[12] Nevertheless, among many other disruptions, gold shifted the focus South. Pernambuco, Bahia, and the entire Northeast were eclipsed by the South of Brazil and that shift in focus has never been reversed.[13]

19th century: a province, then a state

Pernambuco's response to the nationhood of Brazil seems to have been rebellion. Pernambuco was the site of some of the most important rebellions and insurrections in Brazilian history, especially in the 19th century. See Also Rebellions and revolutions in Brazil, Pernambucan Revolt, Cabanada, April Revolt (Pernambuco) At one point Pernambuco led much of the Northeast region in a very short-lived independent Confederation of the Equator.

The end of slavery and the beginning of the republic

In 1888, under the influence of increasingly urban society, and with the advocacy of intellectuals such as Pernambucan politician Joaquim Nabuco, slavery was abolished.[14] However, freedom for the slaves did little or nothing to improve life for the underclass. Economic downturns were used to cut wages, children were paid almost nothing, and violence ruled.[15] In those days before antibiotics there were major epidemics, fourteen between 1849 and 1920.[16]

20th century

The twentieth century did bring better communication and transportation which would slowly allow development. But for the poor employed in the sugar industry, as late as the 1960s infant mortality in this labor segment was nearly half of live births.[17] Politically, the century was dominated by two periods of dictatorship, ruled by Getúlio Vargas for most of the period from 1930 to 1954.[18] and the military dictatorship from 1964 to 1985[19]

Post-dictatorship progress

Since the end of military rule, there is still an underemployed and under-fed underclass. However, quality of life has improved along with industrial development. Pernambuco has also become a major tourist destination. Statistics from the turn of the millennium show a sharp and continuing improvement. According to estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study, the infant mortality rate declined 6.2 percent annually between 1990 and 2015: from 90.4 infant deaths per 1000 live births in 1990, to 13.4 deaths/1000 live births in 2015.[20] The homicide rate in Recife, still higher than the average for Brazil, declined by about 6% per annum during the period from 2000 to 2012.[21]

Income inequality remains a problem; in 2000, the state had a Gini coefficient of 0.59,[22] with wealth and resources being concentrated at the top.

الديمغرافيا

Population

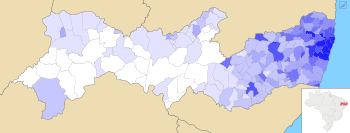

According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), at the last census in 2010 there were 8,745,000 people residing in the state. In 2020, an estimated 9,616,621 people lived in the state.[23] The population is concentrated along the coast in the Recife Metropolitan Region.

Urbanization: 77% (2006); Population growth: 1.2% (1991–2000); Houses: 2,348,000 (2006).[24]

Religion

Religion in Pernambuco (2010)[25][26]

The majority of the state's inhabitants are Catholic; while more than 86% of the state is Christian.

In 2010, 5,834,601 inhabitants identified as Roman Catholic (65.95%), 1,788,973 as Evangelical (20.34%): of these, 1,102,485 were Pentecostal (12.53%), and 376,880 were Evangelical Protestant (4.28%) and 309,608 other Evangelical (3.52%). 123,798 inhabitants identified as spiritists (1.41%), 43,726 as Jehovah's Witnesses (0.50%), 26,526 as Brazilian Apostolic Catholics (0.30%) and 6,678 as Eastern Orthodox(0.08%).

914,954 had no religion (10.40%): of these, 10,284 identified as atheists (0.12%) and 5,638 as agnostics (0.06%). 80,591 followed all other religions not listed above (0.90%), and 9,805 did not know or did not declare (0.12%).[25][26]

The former Latin Catholic Territorial Prelature of Pernambuco became the Metropolitan Archdiocese of Olinda & Recife, with these suffragan dioceses in its ecclesiastical province (all in Pernambuco) : Diocese of Afogados da Ingazeira, Diocese of Caruaru, Diocese of Floresta, Diocese of Garanhuns, Diocese of Nazaré, Diocese of Palmares, Diocese of Pesqueira, Diocese of Petrolina and Diocese of Salgueiro.

Racial/Ethnic composition

The results of the National Household Sample Survey (PNAD) conducted in 2008 led to the following estimates of race or skin color: 4,799,000 Brown (Multiracial) people (54.87%), 3,307,000 White people (37.81%), 561,000 Black people (6.42%), 41,000 Indigenous people (0.47%) and 31,000 Asian people (0.36%).[27]

Due to the legacy of slavery and the sugarcane plantations, it has been observed that those of mixed African and Portuguese ancestry are more common on the coast, while Mamelucos (those of mixed Amerindian and Portuguese ancestry) are more common in the interior Sertão region.[28]

According to a genetic study from 2013, Pernambucans have 56.8% European, 27.9% African and 15.3% Amerindian ancestries.[29]

Largest cities

الاقتصاد

المواشي

According with IBGE 2007, Pernambuco has the 2nd largest livestock portfolio in the Northeast region and the 8th of البرازيل.

| الحيوان أو المنتج | عدد الرؤوس | الترتيب على الشمال الشرقي & % |

الترتيب على البرازيل & % |

|---|---|---|---|

| الماعز | 1595069 | 2nd - 18.48% | 2nd - 16.88% |

| الخراف | 1256270 | 4th - 13.53% | 5th - 7.74% |

| الماشية | 2219892 | 4th - 7.74% | 16th - 1.11% |

| ألبان البقر | 662078000 liters | 2nd - 19.86% | 9th - 2.54% |

| الخنازير | 495957 | 5th - 7.35% | 14th - 1.38% |

| الدواجن | 31916818 | 1st - 24.24% | 7th - 2.83% |

| بيض الدجاج | 142518000 dozens | 1st - 30.56% | 6th - 4.81% |

| سمان | 605371 | 1st - 43.24% | 4th - 7.98% |

| بيض السمان | 9390000 dozens | 1st - 51.43% | 4th - 7.17% |

| الخيول | 125976 | 5th - 8.81% | 15th -2.25% |

| حمير | 100944 | 5th - 9.50% | 5th - 8.68% |

| بغال | 54812 | 4th - 7.97% | 7th - 4.08% |

| جاموس | 19239 | 2nd - 16.04% | 11th - 1.70% |

| أرانب | 2383 | 2nd - 6.45% | 9th - 0.82% |

| العسل | 1177000 kg | 4th - 10.15% | 9th - 3.39% |

الزراعة

|

|

S - موسمي; P - زراعة دائمة; + - آلاف الوحدات

إثانول

البنية التحتية

الموانئ

المدن الرئيسية

| الترتيب | المدينة | التعداد (2009) | GDP (R$x1000)(2007)[34]. | GDP PC (R$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | رصيفي | 1,561,659 | 20,718,107 | 13,510 |

| 2 | Jaboatão dos Guararapes | 687,688 | 5,578,363 | 8,384 |

| 3 | Olinda | 397,268 | 2,179,183 | 5,567 |

| 4 | Paulista | 319,373 | 1,367,111 | 4,449 |

| 5 | Caruaru | 298,501 | 1,993,295 | 6,895 |

| 6 | Petrolina | 281,851 | 1,932,517 | 7,202 |

| 7 | Cabo de Santo Agostinho | 171,583 | 2,813,188 | 17,244 |

| 8 | Camaragibe | 143,210 | 492,113 | 3,608 |

| 9 | Garanhuns | 131,313 | 742,593 | 5,941 |

| 10 | Vitória de Santo Antão | 126,399 | 745,504 | 6,149 |

| 11 | Igarassu | 100,191 | 734,430 | 7,834 |

| 12 | São Lourenço da Mata | 99,945 | 310,748 | 3,261 |

| 13 | Abreu e Lima | 96,266 | 567,474 | 6,154 |

| 14 | Santa Cruz do capibaribe | 80,330 | 332,112 | 4,507 |

| 15 | Serra Talhada | 80,294 | 434,704 | 5,705 |

| 16 | Araripina | 79,877 | 255,578 | 3,368 |

| 17 | Ipojuca | 75,512 | 5,354,635 | 76,418 |

| 18 | Gravatá | 75,229 | 306,637 | 4,284 |

| 19 | Goiana | 74,424 | 457,986 | 6,379 |

| 20 | Belo Jardim | 74,028 | 504,735 | 7,113 |

| 21 | Carpina | 68,070 | 351,448 | 5,375 |

| 22 | Arcoverde | 68,000 | 290,529 | 4,479 |

| 23 | Ouricuri | 66,978 | 200,880 | 3,186 |

| 24 | Pesqueira | 64,454 | 236,259 | 3,852 |

| 25 | Escada | 62,604 | 233,562 | 3,902 |

| RMR | Recife metropolitan area | 3,768,902 | 40,872,963 | 10,845 |

| State | PERNAMBUCO | 8,810,256 | 62,255,687 | 7,337 |

الهامش

- ^ "IBGE".

- ^ "Radar IDHM: evolução do IDHM e de seus índices componentes no período de 2012 a 2017" (PDF) (in Portuguese). PNUD Brasil. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Estimativas 2019 população Regiões Metropolitanas". agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br (in البرتغالية البرازيلية). Retrieved 2021-04-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Spilimbergo, Antonio; Srinivasan, Krishna (2019-03-14). Chapter 12 The Subnational Fiscal Crisis (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). International Monetary Fund. ISBN 978-1-4843-3974-9.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةEB1911 - ^ Hemming, John, Red Gold: The Conquest of the Brazilian Indians. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978, p. 9

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Dutch in Brazil 1624-1654, Archon Books, 1973

- ^ "Raulmendesilva.pro.br". Raulmendesilva.pro.br. Archived from the original on 1 مارس 2012. Retrieved 6 أبريل 2012.

- ^ Prefeitura Municipal de Monteiro. I Encontro Regional das Rendas Renascença.[dead link]

- ^ Peter Eisenberg, The Sugar Industry in Pernambuco: Modernization Without Change, 1840-1910, University of California Press, ch 1.

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Golden Age of Brazil: 1695-1750, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1962. Ch. V

- ^ Stuart B Schwartz, Sugar Plantations in the Formation of Brazilian Society: Bahia, 1550-1835 p. 160

- ^ C. R. Boxer, The Golden Age of Brazil: 1695-1750, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1962

- ^ E. Bradford Burns, A History of Brazil, 2 ed. Columbia University Press, New York, pp. 271-276

- ^ Robert Levine, Pernambuco in the Brazilian Federation, 1889-1937, p. 165.

- ^ Robert Levine, Pernambuco in the Brazilian Federation, 1889-1937, pp. 16&17

- ^ Kit Sims Taylor, Sugar and Underdevelopment of Northeastern Brazil 1500-1970, University Presses of Florida, p. 5

- ^ Richard Graham, "A century of Brazilian History since 1865: Issues and Problems, A. Knopf, New York, p. 137

- ^ E. Bradford Burns, A History of Brazil, 3 ed. Columbia University Press, New York, p. 444

- ^ Szwarcwald, C.L., Almeida, W.d., Teixeira, R.A. et al. "Inequalities in infant mortality in Brazil at subnational levels in Brazil, 1990 to 2015." Popul Health Metrics 18, 4 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-020-00208-1

- ^ D. Pereira, C.Mota, and M. Andresen, "The Homicide Drop in Recife, Brazil: A Study of Crime Concentrations and Spatial Patterns", Homicide Studies 2017, Vol. 21(1) 21&27.

- ^ Funari, Pedro Paulo Pereira (2017), Bértola, Luis; Williamson, Jeffrey, eds. (in en), Inequality, Institutions, and Long-Term Development: A Perspective from Brazilian Regions, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 113–142, doi:, ISBN 978-3-319-44621-9, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44621-9_6, retrieved on 2021-04-11

- ^ "Population Estimates | IBGE". www.ibge.gov.br. Retrieved 2021-04-11.

- ^ Source: PNAD.

- ^ أ ب «Censo 2010». IBGE

- ^ أ ب «Análise dos Resultados/IBGE Censo Demográfico 2010: Características gerais da população, religião e pessoas com deficiência» (PDF)

- ^ Tabela 262: População residente, por cor ou raça, situação e sexo (PDF) (in البرتغالية). IBGE, Pernambuco, Brazil. 2008. ISBN 978-85-240-3919-5. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ^ "Notas nordestinas – Terra – Antonio Riserio". Terramagazine.terra.com.br. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Saloum De Neves Manta, Fernanda; Pereira, Rui; Vianna, Romulo; Rodolfo Beuttenmüller De Araújo, Alfredo; Leite Góes Gitaí, Daniel; Aparecida Da Silva, Dayse; De Vargas Wolfgramm, Eldamária; Da Mota Pontes, Isabel; Ivan Aguiar, José; Ozório Moraes, Milton; Fagundes De Carvalho, Elizeu; Gusmão, Leonor (2013). "Revisiting the Genetic Ancestry of Brazilians Using Autosomal AIM-Indels". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e75145. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...875145S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075145. PMC 3779230. PMID 24073242.

- ^ "Estimativas da população residente nos municípios brasileiros com data de referência em 1º de julho de 2011" [Estimates of the Resident Population of Brazilian Municipalities as of July 1, 2011] (in البرتغالية). Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. 30 August 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^ http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/economia/ppm/2007/ppm2007.pdf Brazil livestock statistics 2007

- ^ http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/economia/pam/2002/pam2002.pdf Brazil Agriculture statistics 2002

- ^ IBGE, [http://www.ibge.gov.br/

- ^ GDP City by City 2007 IBGE

وصلات خارجية

- (البرتغالية) Official website

- (إنگليزية) Brazilian Tourism Portal

- (البرتغالية) Tourism Official Website

- (إنگليزية) Cities of Pernambuco

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 maint: url-status

- CS1 البرتغالية البرازيلية-language sources (pt-br)

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Articles with dead external links from April 2023

- CS1 البرتغالية-language sources (pt)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using infobox settlement with unknown parameters

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from January 2010

- پرنامبوكو

- البرازيل الهولندية

- ولايات البرازيل

- الاقليم الشمالي الشرقي، البرازيل