عنتاب

غازيعنتپ

Gaziantep | |

|---|---|

| الإحداثيات: 37°03′57″N 37°22′41″E / 37.06583°N 37.37806°E | |

| البلد | |

| المنطقة | شرق الأناضول |

| المحافظة | غازيعنتپ |

| الحكومة | |

| • العمدة | فاطمة شاهين (العدالة والتنمية) |

| المساحة | |

| • Metropolitan municipality | 7٫642 كم² (2٫951 ميل²) |

| التعداد (تقدير 31/12/2024)[1] | |

| • Metropolitan municipality | 1٬376٬352 |

| • الكثافة | 212/km2 (550/sq mi) |

| • العمرانية | 1٬393٬289 |

| صفة المواطن | Aintaban[2] |

| GDP | |

| • Metropolitan municipality | TRY 148.558 billion US$ 16.545 billion (2021) |

| • Per capita | TRY 70,228 US$ 7,819 (2021) |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+2 (توقيت شرق أوروپا) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+3 (توقيت شرق أوروپا الصيفي) |

| الرمز البريدي | 27x xx |

| مفتاح الهاتف | 342 & 343 |

| لوحة المركبات | 27 |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www.gaziantep.gov.tr |

عنتاب أو غازيعنتپ Gaziantep، هي عاصمة محافظة غازيعنتپ في جنوب تركيا حالياً يبلغ عدد سكانها 853,513 نسمة تعتبر سادس أكبر مدينة في تركيا. كانت المدينة تعرف لدى العرب والسلاجقة والعثمانيين باسم عنتاب لكن البرلمان التركي أضاف كلمة غازي لاسم المدينة يوم 8 فبراير/شباط 1921 فأصبحت غازي عنتاب. هي من الأقاليم السورية الشمالية التي ضمت إلى تركيا بموجب معاهدة سيفر عام 1920 بين تركيا من جهة وبريطانيا وفرنسا من جهة أخرى.

تعتبر من المدن الصناعية الهامة في تركيا خاصة وفي المنطقة عامة، تشتهر بالكباب العنتبلي وبالفستق العنتبلي، كما تشتهر بصناعة حلوى البقلاوة. معظم سكان المدينة من العرب.

The city is thought to be located on the site of ancient Antiochia ad Taurum and is near ancient Zeugma. Sometime after the Byzantine-ruled city came under the Seljuk Empire, the region was administered by Armenian warlords. In 1098, it became part of the County of Edessa, a Crusader state, though it continued to be administered by Armenians, such as Kogh Vasil.

Aintab rose to prominence in the 14th century as the fortress became a settlement, hotly contested by the Mamluk Sultanate, Dulkadirids, and the Ilkhanate. It was besieged by Timur in 1400 and the Aq Qoyunlu in 1420. The Dulkadirid-controlled city fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1516 sometime before the Battle of Marj Dabiq.

As of the 2024 census, the Gaziantep province (metropolitan municipality) was home to 2,193,363 inhabitants, of whom around 1.8 million lived in the urban area. It is the fifth-most populous city in Turkey. Gaziantep is a diverse city inhabited mostly by ethnic Turks and a significant minority of Kurds and Syrian refugees. It was historically populated by Turkomans, Armenians, Jews, and a plethora of other ethnic groups.

In February 2023, the city was significantly damaged by the 2023 Turkey–Syria earthquake. Although three of the four most significant quakes of the earthquake occurred within the Gaziantep Province, the overall destruction to the city was reportedly less intense than that of Kahramanmaraş, Hatay, Malatya, and Adıyaman provinces, making it the fifth most affected province at 944 buildings collapsed.[4] The destruction was reportedly much higher in the rural districts of Nurdağı and Islahiye, although a number of historic sites within the city such as mosques and Gaziantep Castle also suffered significant damages. Due to its size, location and relative intactness, the city served as a regional hub for international organizations and NGOs for earthquake relief and reconstruction after the earthquake.

التسمية

Due to the city's contact with various ethnic groups and cultures throughout its history, the name of the city has many variants and alternatives, such as:

- Hantab, Hamtab, or Hatab as known by the Crusaders,[5][6]

- Antab and its variants in vulgar Turkish and Armenian since 17th century the latest,[7][8]

- Aīntāb (عين تاب) in Ottoman Turkish,

- Gazi Ayıntap in official Turkish after February 1921, when the Turkish parliament honored the city as غازى عینتاب Ghazi Aīntāb to commemorate its resistance to the French Siege of Aintab during the Franco-Turkish War,

- Gaziantep in official Turkish after 1928,[9]

- 'Aīntāb (عينتاب) in Arabic,

- Êntab or Dîlok in Kurdish,[10]

- Aïntab or Verdun Turc in French.[11]

The several theories for the origin of the current name include:[citation needed]

- Aïn, an Arabic and Aramaic word meaning "spring", and tab as a word of praise.

- Antep could be a corruption of the Arabic 'aīn ṭayyib meaning "good spring".[12] However, the Arabic name for the city is spelled with t (ت), not ṭ (ط).

- Ayin dab or Ayin debo in Aramaic, meaning "spring of the wolf"

التاريخ

العصر الهليني

Gaziantep is the probable site of the Hellenistic city of Antiochia ad Taurum[14] ("Antiochia in the Taurus Mountains").

الفتح الإسلامي

During its early history, Aintab was largely a fortress overshadowed by the city of Dülük, some 12 km to the north. Aintab came to prominence after an earthquake in the 14th century devastated Dülük.[2] Following the Muslim conquest of the Levant, the region passed to the Umayyads in 661 AD and the Abbasids in 750. It was ravaged several times during the Arab–Byzantine wars. After the disintegration of the Abbasid dynasty, the city was ruled successively by the Tulunids, the Ikhshidids, and the Hamdanids.[citation needed] In 962, it was recaptured by the Byzantines, upon the expansion led by Nikephoros II Phokas.[15]

After Afshin Bey captured the fortress in 1067, Aintab fell to Seljuk rule[16] and was administered by Seljuk emirs of Damascus. One of these emirs, Tutush I appointed Armenian noble Thoros of Edessa as the governor of the region.[17]

It was captured by the Crusaders and united to the Maras Seigneurship in the County of Edessa in 1098. The region continued to be ruled by independent or vassalized Armenian lords, such as Kogh Vasil.[18] It reverted to the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm in 1150, was controlled by the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia between 1155–1157 and 1204–1206 and captured by the Zengids in 1172 and the Ayyubids in 1181. It was retaken by the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm in 1218.[citation needed]

With the turn of the 13th-century, Dülük became one of Aintab's dependencies according to geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi. In the next century, Aintab was the capital of its district and a town with fine markets much frequented by merchants and travellers, while Dülük was in ruins, according to Abulfeda.[19] Still, Aintab continued to be hotly contested throughout these centuries.[2] It was besieged by the Mongols in 1270.[2]

It repeatedly changed hands between the Ilkhanate and the Mamluk Sultanate or the Dulkadirids, a Turkoman vassal state of the Mamluks. Gaziantep was near the southern frontier of the Dulkadir emirate, and on several occasions it slipped out of their control.[2] The Ilkhans ruled over it between 1260 and 1261, 1271–1272, 1280–1281 and 1299–1317. The Mamluks controlled the city between 1261 and 1271, 1272–1280, 1281–1299, 1317–1341, 1353–1378, 1381–1389. It was unsuccessfully besieged by the Dulkadir leader Sevli Beg in 1390. Although the Mamluks and their Dulkadirid vassals could control the city from 1395 until the Ottoman conquest in 1516, the city was besieged by Timur in 1400, and then in 1420 by the leader Qara Qoyunlu of Kara Yusuf.[2]

These attacks all caused destruction and suffering among the local population. But at the same time, the city was "acquiring a reputation as a cultured urban center". Badr al-Din al-Ayni, an Aintab native who became a successful diplomat, judge, and historian under the Mamluks, wrote at the end of the 1300s that the city was called "little Bukhara" because so many scholars came to study there. Ayni also left a firsthand account of the suffering caused during Sevli Beg's siege in 1390.[2]

Another rough patch for Aintab's people came in the late 1460s, when the Dulkadir prince Şehsuvar rebelled against the Mamluks.[2] Mamluk forces captured Aintab in May 1468, driving out Şehsuvar's forces; a report by the governor of Aleppo indicates that resistance had been fierce. Just a month later, Şehsuvar recaptured Aintab after four "engagements" with Mamluk forces. After Şehsuvar's final defeat and public execution by the Mamluks in 1473, Gaziantep enjoyed a period of relative peace and stability under his brother and successor Alaüddevle. Alaüddevle appears to have considered Gaziantep an important possession and commissioned several constructions in the city, including a reservoir and a large mosque in the middle of town. The city's fortress was also renovated, completed in 1481. These repairs were likely ordered by the Mamluk sultan Qaitbay during his tour of northern Syria in 1477; his name is inscribed above the entrance portal, perhaps symbolically marking his territory.[2]

The end of the Dulkadir principality came around 1515. Alaüddevle refused to fight alongside the Ottomans at the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514. The Ottomans used this as a pretext to overthrow him, and in June 1515 he was executed.[2] As Alaüddevle had been a Mamluk vassal, the Mamluks considered this an affront, and the Mamluk sultan Qansuh al-Ghawri mobilized an army and marched north towards Aleppo.[2]

The conflict over the region meant that in Gaziantep, anxieties about the fate of the city and its surroundings must have been high. Later court records from the early 1540s provide documentary evidence of "dislocation and loss of population" as people fled; this may have been more pronounced in rural areas than in the city itself.[2]

العصر العثماني

The Ottoman Empire captured Gaziantep just before the Battle of Marj Dabiq in 1516, under the reign of Sultan Selim I. In the Ottoman period, Aintab was a sanjak centred initially in the Dulkadir Eyalet (1516–1818), and later in the Aleppo vilayet (1908–1918).[citation needed] It was also a kaza in the Aleppo vilayet (1818–1908). The city established itself as a centre for commerce due to its location straddling trade routes.[citation needed]

Although it was controlled by the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia only between 1155–1157 and 1204–1206, for most of the last two millennia, Gaziantep hosted a large Armenian community.[citation needed] Armenians played a significant role in the city's history, culture, welfare, and prosperity. These communities no longer exist in the city due to the Hamidian massacres in 1895 and the Armenian genocide in 1915.[citation needed]

Gaziantep served a significant trade route within the Ottoman Empire. Armenians were active in manufacturing, agriculture production and, most notably, trade, and became the wealthiest ethnic group in the city,[20] until their wealth was confiscated during the Armenian genocide.[21]

معركة مرج دابق

At the beginning of his campaign against the Mamluks in 1516, the Ottoman sultan Selim I brought his army to Gaziantep en route to Syria. The city's Mamluk governor, Yunus Beg, submitted to Selim without a fight and gave him the keys to the castle on 20 August.[2] The next day, 21 August, Selim set up camp outside the city "with great majesty and pomp" and held meetings with local military commanders to discuss strategy for the upcoming battle.[2] The fateful Battle of Marj Dabiq took place just days later, on 24 August. Gaziantep, although not an active battle site, thus played a strategic role in the Ottoman conquest of the Mamluk sultanate.[2]

The Ottoman victory at Marj Dabiq had profound consequences for Gaziantep, although its inhabitants had no way of knowing at the time. For the first time in almost 1,000 years, Gaziantep was located in the middle of an empire rather than a contested border region. It lost its strategic importance, but also its vulnerability to attack. For four centuries, until the French occupation in 1921, Gaziantep was relatively peaceful.[2]

Economic recovery

In the short term, though, Gaziantep was still reeling from the instability before (and after) the Ottoman conquest.[2] During that period, Gaziantep had suffered from "depredation", as well as fear caused by political uncertainty.[2] Besides political conflict, the city's economic slump at this time can also be partly attributed to a general decline in commerce in the eastern Mediterranean region that caused a general economic downturn in the region in the early 1500s.[2]

Only around the 1530s, when the Ottoman authorities turned their attention to the territories recently conquered from Dulkadir, do cadastral records indicate renewed prosperity in Gaziantep.[2] An important event was Süleyman the Magnificent's successful Mesopotamian campaign against Safavid Iran in 1534-36, which took Baghdad and increased the security of trade routes in Gaziantep's region.[2] As with the earlier economic downturn, the renewed prosperity in Gaziantep in the 1530s was part of a broader regional pattern of economic growth during this period.[2]

As a disclaimer – some of this apparent economic growth may be an artifact of using tax documents as a source. Tax assessors may have simply been doing more accurate counts in later surveys, or the government might have been applying more strict scrutiny as their control increased.[2] Part of this was deliberate – the Ottomans had a policy of lowering taxes in recently conquered territories, both to placate locals and to provide an economic stimulus to help war-torn areas recover.[2] Later, as their control solidified, the authorities would raise taxes again. According to Leslie Peirce, this seems to have been the case in Gaziantep – tax rates in 1536 were significantly lower than the rates in 1520, which she assumes were the pre-Ottoman rates. The rates went up again in the 1543 survey, which she interprets as the Ottomans raising taxes again in the meantime.[2]

Administrative changes

The Dulkadir emirate did not simply go away immediately after the Ottoman victory at Marj Dabiq. It stuck around as an Ottoman vassal until 1522, when the last Dulkadir ruler "resisted discipline by the Ottoman administration". The Ottomans had him executed and officially dismantled the Dulkadir principality, annexing its territories to the empire to form the beglerbeglik of Dulkadir.[2]

Despite being part of the former Dulkadir territories, though, the sanjak of Gaziantep was initially put under the beglerbeglik of Aleppo instead of Dulkadir. This indicates how, just as in the Mamluk period, Gaziantep was then seen more as part of northern Syria than as part of Anatolia. The area was "culturally mixed", and many locals were bilingual in Turkish and Arabic (as well as other languages). Gaziantep's cultural and economic ties were mostly with Aleppo, which was a major international center of trade.[2]

At some point in the 1530s, Gaziantep was moved into the beglerbeglik of Dulkadir, whose capital was Maraş. Even though it was now administratively part of Dulkadir, Gaziantep remained commercially more connected to Aleppo.[2]

17th through 19th centuries

The 17th-century Turkish traveller Evliya Çelebi noted it had 3,900 shops and two bedestens.

In 1818, Gaziantep was moved back into the Aleppo province.[2]

By the end of the 19th century, Aintab had a population of about 45,000, two-thirds of whom were Muslim—largely Turkish, but also partially Arab. A large community of Christians lived in the Armenian community. In the 19th century, considerable American Protestant Christian missionary activity occurred in Aintab.[22][23] In particular, Central Turkey College was founded in 1874 by the American Mission Board and largely served the Armenian community. The Armenians were systemically slaughtered during the Hamidian massacres in 1895 and later the Armenian genocide in 1915.[24][25] Consequently, the Central Turkey College was transferred to Aleppo in 1916.

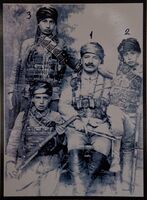

Republic of Turkey

After the First World War and Armistice of Mudros, Gaziantep was occupied by the United Kingdom on 17 December 1918, and it was transferred to France on 5 November 1919.[26] The French Armenian Legion was also involved in occupation. In April 1920 irregular Turkish troops known as Kuva-yi Milliye besieged the city,[27] but the 10-month-long battle resulted in French victory.[28] Around 6,000 Turkish civilians were killed in the process.[29]

The French made the last attempt to revive the Armenian community in the city during the Siege of Aintab, where the Armenians who fled the genocide were promised their homes back in their native lands. However, on 25 December 1921, the Treaty of Ankara was signed, and as a result, the French evacuated the city.

According to Ümit Kurt, born in modern-day Gaziantep and an academic at Harvard's Center for Middle East Studies, "The famous battle of Aintab against the French … seems to have been as much the organised struggle of a group of genocide profiteers seeking to hold onto their loot as it was a fight against an occupying force. The resistance … sought to make it impossible for the Armenian repatriates to remain in their native towns, terrorising them [again] to make them flee. In short, not only did the local … landowners, industrialists, and civil-military bureaucratic elites lead to the resistance movement, but they also financed it to cleanse Aintab of Armenians."[30] The same Turkish families who made their wealth through the expropriation of Armenians in 1915 and 1921/1922 continued to dominate the city's politics through the one-party period of the Republic of Turkey.[31]

In 2013, Turkey, a member state of NATO, requested deployment of MIM-104 Patriot missiles to Gaziantep to be able to respond faster in a case of military operation against Turkish soil in the Syrian Civil War, which was accepted.[32]

On 6 February 2023, the city and nearby areas were devastated by catastrophic earthquakes. Around 900 buildings collapsed[33] and 10,777 other buildings were heavily damaged in the city, which have been slated for demolition.[34] Historic buildings including the Gaziantep Castle, the Şirvani Mosque and the Liberation Mosque were also heavily damaged.

Geography

The city is located on the Aintab plateau.

Climate

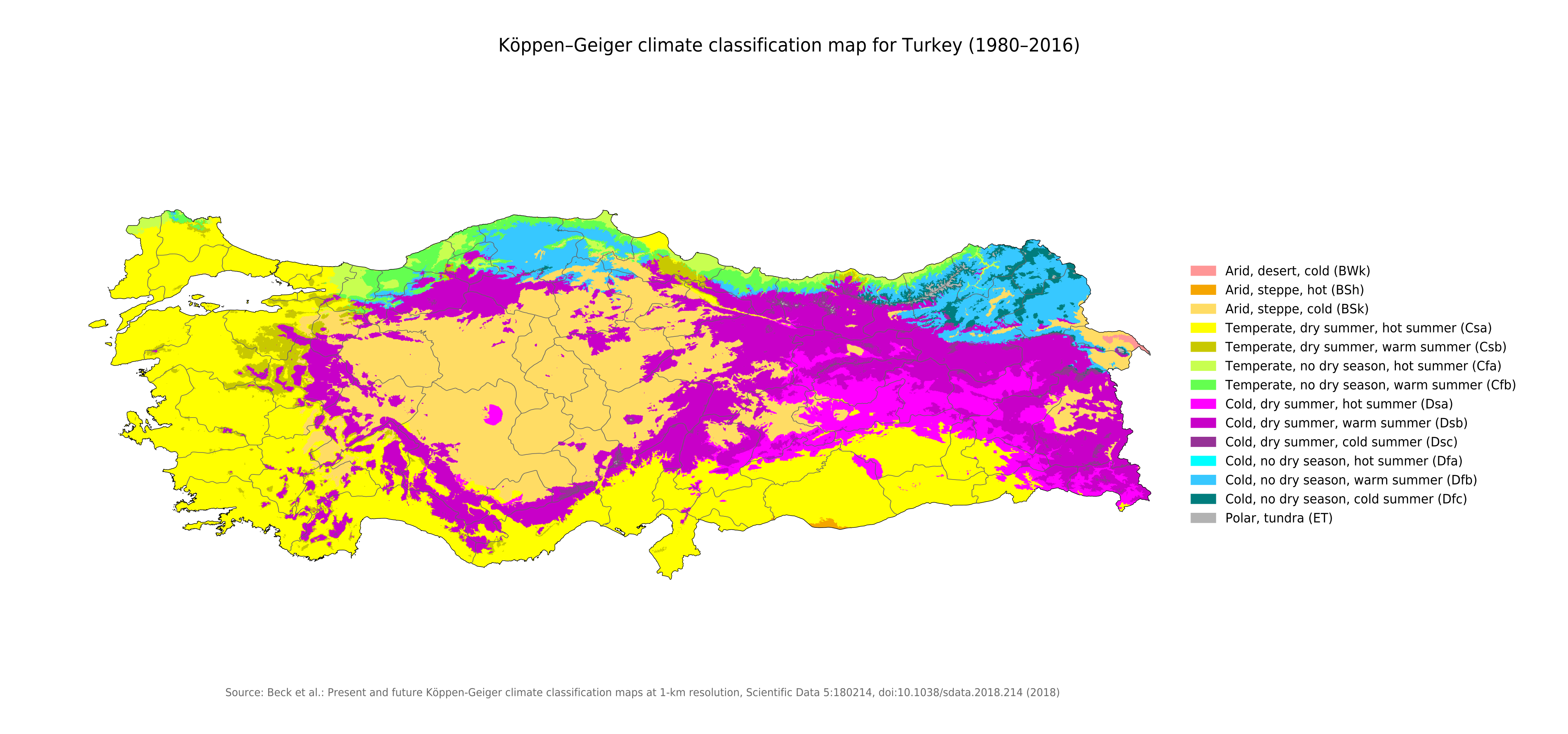

Gaziantep has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa, Trewartha: Cs), with very hot, dry summers and cool, wet and often snowy winters.

According to 1966 data, on average, Gaziantep experiences 4.6 snowy days per winter with 10 days of snow cover, along with 2.5 days of hail.[36]

Highest recorded temperature: 44.0 °C (111.2 °F) on 29 July 2000 and 14 August 2023

Lowest recorded temperature: −17.5 °C (0.5 °F) on 15 January 1950[37]

| بيانات المناخ لـ Gaziantep (1991–2020, extremes 1940–2023) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| القصوى القياسية °س (°ف) | 19.0 (66.2) |

24.3 (75.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

34.0 (93.2) |

37.8 (100.0) |

40.2 (104.4) |

44.0 (111.2) |

44.0 (111.2) |

40.8 (105.4) |

36.4 (97.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

25.2 (77.4) |

44.0 (111.2) |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °س (°ف) | 8.4 (47.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

15.0 (59.0) |

20.3 (68.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

31.9 (89.4) |

36.0 (96.8) |

36.2 (97.2) |

31.8 (89.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

10.4 (50.7) |

22.3 (72.1) |

| المتوسط اليومي °س (°ف) | 3.9 (39.0) |

5.1 (41.2) |

9.3 (48.7) |

14.0 (57.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

24.8 (76.6) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.7 (83.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

17.7 (63.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

5.6 (42.1) |

16.0 (60.8) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °س (°ف) | 0.4 (32.7) |

0.9 (33.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

8.3 (46.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

18.1 (64.6) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

11.7 (53.1) |

5.4 (41.7) |

1.9 (35.4) |

10.5 (50.9) |

| الصغرى القياسية °س (°ف) | −17.5 (0.5) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

−11 (12) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

0.4 (32.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.8 (51.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−15 (5) |

−17.5 (0.5) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار mm (inches) | 98.1 (3.86) |

89.6 (3.53) |

68.9 (2.71) |

56.1 (2.21) |

32.9 (1.30) |

9.2 (0.36) |

10.6 (0.42) |

8.5 (0.33) |

13.1 (0.52) |

42.6 (1.68) |

67.5 (2.66) |

104.5 (4.11) |

601.6 (23.69) |

| Average precipitation days | 12.3 | 11.5 | 11.3 | 10.1 | 7.5 | 2.27 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 1.9 | 6.2 | 8.1 | 11.7 | 84.1 |

| متوسط الرطوبة النسبية (%) | 74.2 | 70.8 | 64.7 | 61.3 | 56.0 | 47.5 | 43.9 | 46.9 | 49.4 | 57.2 | 67.2 | 73.7 | 59.3 |

| Mean monthly ساعات سطوع الشمس | 107.1 | 119.7 | 161.4 | 189.8 | 220.9 | 261.2 | 275.9 | 268.2 | 232.2 | 197.1 | 149.2 | 96.3 | 2٬149٫5 |

| المتوسط اليومي ساعات سطوع الشمس | 3.6 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 6.4 | 7.1 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 7.8 | 6.4 | 5.1 | 3.4 | 6.3 |

| Source 1: Turkish State Meteorological Service[38][37] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (humidity, sun 1991-2020),[39] Meteomanz[40] | |||||||||||||

السياسة

The current mayor of Gaziantep is Fatma Şahin,[41] who had previously served as the minister of family and social policies in the third cabinet of Erdoğan. The city has historically supported conservative parties such as Democrat Party, Justice party and AKP, although support for opposition parties has been growing in recent years. Most significantly on the 31 March mayoral elections, the district governor candidates of the main opposition party CHP have won in the metropolitan district of Şehitkâmil, alongside two rural districts, tying with AKP on the number of districts won in the province at 3.[42]

العمد

| عمد عنتاب | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| العمدة | سنوات الخدمة | ||

| فاطمة شاهين | 2014–الآن | ||

| د. عاصم گوزلباي | 2004–2014 | ||

| جلال دوغان | 1989–2004 | ||

| عمر عرپجيأوغلو | 1984–1989 | ||

الاقتصاد

Gaziantep is famous for its regional specialities: copperware and "Yemeni" sandals, specific to the region, are two examples. The city is an economic centre for Southeastern and Eastern Turkey. The number of large industrial businesses established in Gaziantep comprise four percent of Turkish industry in general, while small industries comprise six percent. Also, Gaziantep has the largest organised industrial area in Turkey and holds first position in exports and imports.[43] The city is the centre of the green olive oil-based Nizip Soap industry.

Traditionally, commerce in Gaziantep was centre in covered markets known as 'Bedesten' or 'Hans', the best known of which are the Zincirli Bedesten, Hüseyin Pasha Bedesten and Kemikli Bedesten.

Gaziantep also has a developing tourist industry. Development around the base of the castle upgrades the beauty and accessibility to the castle and to the surrounding copper workshops. New restaurants and tourist-friendly businesses are moving into the area. In comparison with some other regions of Turkey, tourists are still a novelty in Gaziantep and the locals make them very welcome.[citation needed] Many students studying the English language are willing to be guides for tourists.

Gaziantep is one of the leading producers of machined carpets in the world. It exported approximately US$700 million of machine-made carpets in 2006. There are over 100 carpet facilities in the Gaziantep Organized Industrial Zone.[citation needed]

With its extensive olive groves, vineyards, and pistachio orchards, Gaziantep is one of the important agricultural and industrial centres of Turkey.[citation needed]

Gaziantep is the centre of pistachio cultivation in Turkey, producing 60،000 metric ton (59،000 long ton; 66،000 short ton) in 2007, and lends its name to the Turkish word for pistachio, Antep fıstığı, meaning "Antep nut".

Gaziantep is the main centre for pistachio processing in Turkey, with some 80% of the country's pistachio processing (such as shelling, packaging, exporting, and storage) being done in the city.[44] "Antep fıstığı" is a protected geographical indication in Turkey; it was registered under this status in 2000.[44]

In 2009, the largest enclosed shopping centre in the city and region, Sanko Park, opened, and began drawing a significant number of shoppers from Syria.[45]

Ties between Turkey and Syria have severely deteriorated since the beginning of the Syrian civil war in 2011.

Demographics

Gaziantep is mostly inhabited by Turks.[46] It is also inhabited by a significant minority of Kurds,[46] about 450 thousand people,[47] and roughly 470 thousand Syrian refugees.[46]

History

In early 14th century, Arab geographer Dimashki noted that the people of Aintab were Turkomans.[19] Aintab continued to be Turkish or Turkoman majority through 18th,[48] 19th,[49][50][51][52] and 20th centuries.[53][54][11][5] Armenians inhabited Aintab from at least 10th century until the Armenian genocide.[55] Having abandoned Armenian in favour of Turkish as early as the 16th century,[56] the Armenians of Aintab predominantly spoke Turkish,[57][48][58][59][52] while the usage of Armenian increased after 1850.[56] The city also housed a smaller Jewish minority predominantly of Sephardic origin.[60] The Jewish population quickly decreased in mid-20th century, reaching zero people by 1980s.[61] Unlike most Southeastern Anatolian cities, the city of Gaziantep did not have a significant Kurdish minority until the 20th century, when it saw an increase in its Kurdish population through economically motivated migration from Turkish Kurdistan.[62] Up until the late 2010s, the Kurdish population increased to one fourth of the city and the province with 400,000 - 450,000 Kurds.[47] In the late Ottoman era, the city included a number of Europeans and Americans.[63] Aintab also had a sizable Uzbek minority dating back to the Ottoman rule.[64][65]

| Languages | Speakers | % |

|---|---|---|

| Turkish | 38,281 | 95.7 |

| Arabic | 873 | 2.2 |

| Kurdish | 491 | 1.2 |

| Other | 359 | 0.9 |

| Total | 40,004 | 100 |

Culture

Cuisine

Gaziantep is largely regarded as the city with the richest cuisine in Turkey.[68] It was the first city in Turkey to be designated as a City of Gastronomy by UNESCO in 2015.[69][70] In 2013, Gaziantep baklava became the first Turkish product with a European protected designation of origin and geographical indication.[71]

The cuisine of Aintab was attested to be "rich" by many travellers throughout the centuries. 19th-century British traveller noted:[72]

"The padishah himself would do well to visit Aintab, just to taste the rich food to be found there."

Types of kofta (تركية: köfte; Gaziantep dialect: küfte[73]) include içli küfte (حرفياً 'stuffed kofta'), sini küfte, yoğurtlu küfte, yağlı küfte (حرفياً 'greasy kofta'), tahinli küfte, pendir ekmekli küfte (حرفياً 'kofta with bread and cheese'), and more.[74] Some koftas do not include any meat such as yapma[75] and malhıtalı küfte (حرفياً 'lentil kofta').[76]

Pilafs in the Aintab cuisine often accompany the main dish and are not the main course alone. Traditionally, bulgur is used for the pilafs. The bulgur pilafs can include orzo (Şehriyeli bulgur pilavı; Şʿāreli burgul pilov) or ground beef (Kıymalı aş or Meyhane pilavı, حرفياً 'tavern pilaf').[74]

There are several types of exclusively-Armenian soups in Aintab cuisine. These include vardapet soup and omız zopalı.[74]

Vegetable dishes of Aintab often include meat but can be vegetarian as well. These include dorgama (doğrama), moussaka, bezelye, bakla, kuru fasulye, mutanya, türlü,[74] and kabaklama.[77] Dolma is a very common dish, different variants of which are cooked. One is kış dolması (حرفياً 'winter dolma'), for which dried vegetables, such as squash, eggplants, and peppers are used.

Common sweets include bastık and sucuk.

Local Turkish dialect

The local Turkish dialect of Gaziantep is classified as a part of the Western Turkish dialects based on phonetic and grammatical similarities.[78][79] The dialect carries influences mainly from Armenian and Arabic.[80] The local Turkish dialect of Gaziantep is an integral part of the native identity of the city[81] and is being preserved through often humorous plays by theatrical troupes, such as Çeled Uşaglar (حرفياً naughty children).[82]

Museums

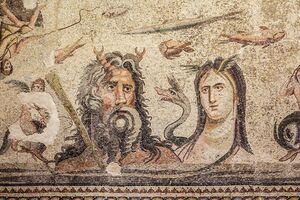

The Gaziantep Museum of Archaeology has collections of ceramic pieces from the Neolithic Age; various objects, figures and seals from the Chalcolithic and Bronze Ages; stone and bronze objects, jewellery, ceramics, coins, glass objects, mosaics and statues from the Hittite, Urartu, Greek Persian, Roman, Commagene, and Byzantine periods.

The Zeugma Mosaic Museum houses mosaics from Zeugma and other mosaics, a total of 1،700 متر مربع (18،000 sq ft).[83][citation needed] It opened to the public on 9 September 2011.[84]

The Hasan Süzer Ethnography Museum, a restored late-Ottoman stone building, has the old life style decoration and collections of various weapons, documents, instruments used in the defence of the city as well as the photographs of local resistance heroes. It was originally built in 1906 as the home of Garouj Karamanoukian.

Some of the other historical remains are the Zeugma (also called Belkıs in Turkish), and Kargamış ruins by the town of Nizip and slightly more to the north, Rumkale.

Yesemek Quarry and Sculpture Workshop is an open-air museum located in the village known by the same name, 30 km (19 mi) south of the town of Islahiye. It is the largest open-air sculpture workshop in the Near East and the ruins in the area date back to the Hittites.

The Gaziantep Defence Museum: before you enter the Panorama Museum located within the Gaziantep Castle, you encounter the statues of three local heroes Molla Mehmet Karayılan, Şehit Mehmet Kâmil and Şahin Bey at the entrance. As you enter the museum, you hear the echoes: "I am from Antep. I am a hawk (Şahin)." The Gaziantep War Museum, in a historic Antep house (also known as the Nakıpoğlu House) is dedicated to the memory of the 6,317 who died defending the city, becoming symbols of Turkey's national unity and resolve for maintaining independence. The story of how the Battle of Antep is narrated with audio devices and chronological panels.

Gaziantep Mevlevi Lodge Foundation Museum

The Antep Mevlevi Lodge in 1638 as a Mevlevi monastery. The dervish lodge is part of the mosque's külliye (Islamic-Ottoman social complex centred around a mosque). It is entered via a courtyard which opens off the courtyard of the mosque. In 2007, the building was opened as the Gaziantep Mevlevi Culture and Foundation Works Museums.

Emine Göğüş Cuisine Museum Gaziantep is known for its cuisine and food culture. A historical stone house built in 1904 has been restored and turned into the Emine Göğüş Cuisine Museum. The museum opened as part of the celebrations for the 87th anniversary of Gaziantep's liberation from French occupation.

Historical sites

Places of worship

Liberation Mosque, the former Armenian Cathedral of the Holy Mother of God (Surp Asdvadzadzin), was converted into a mosque after the liberation of the city from the occupying French forces following the Franco-Turkish War (1918–1921). The French forces which occupied the city between 1918 and 1921 included the French Armenian Legion.

Boyacı Mosque, a historic mosque in the Şahinbey district, was built by Kadı Kemalettin in 1211 and completed in 1357. It has one of the world's oldest wooden minbars which is elaborately adorned with Koranic verses, stars and geometric patterns. Its minaret is considered one of the symbols of the city.

Şirvani Mosque (Şirvani Mehmet Efendi Mosque), also called İki Şerefeli Cami, is one of the oldest mosques of Gaziantep, located in the Seferpaşa district. It was built by Şirvani Mehmet Efendi.

Ömeriye Mosque, a mosque in the Düğmeci district. Tradition states that it was first built during the period of the Islamic Caliphate under the second Caliph, Omar (hence its name), which would make it the oldest known mosque in Gaziantep. The modern mosque was restored at the site in 1850. It is known for its black and red marble mihrab.

Şeyh Fethullah Mosque, a historic mosque built in 1563 and located in Kepenek. It has adjoining Turkish baths and a medrese.

Nuri Mehmet Pasha Mosque, a mosque in Çukur built in 1786 by nobleman Nuri Mehmet Pasha. Between 1958 and 1968, it was changed into museum but was reinstated as a mosque after an extensive restoration.

Ahmet Çelebi Mosque, a mosque in Ulucanlar that was built by Hacı Osman, in 1672. It is noted for its elaborate wooden interior.

Tahtani Mosque, a wooden mosque located in Şahinbey, that was built in 1557. The mosque has a unique red marble mihrab.

Alaüddevle Mosque (Ali Dola Mosque), built by Dulkadir bey Alaüddevle Bozkurt. Its construction started in 1479 and was completed in 1515. It has been restored recently with the addition of a new entrance.

Ali Nacar Mosque, a mosque in Yaprak, Şehitkamil, is one of the biggest mosques in Gaziantep, originally built by Ali Nacar. It was enlarged in 1816.

Eyüpoğlu Mosque, a mosque built by the local Islamic saint Eyüboğlu Ahmet during the 14th century. There has been a major restoration, so much so that the present structure hardly resembles the original building.

Kendirli Church, a church that was built in 1860 by means of the assistance of French missionaries and Napoleon III. It is a Catholic Armenian church. It has a rectangular plan and was built through white cut stones on a foundation of black cut stone within a large garden.

Bazaars

Zincirli Bedesten is the Ottoman-era covered bazaar of Gaziantep and was built in 1781 by Hüseyin Pasha of Darende. From records, it is known that there was formerly an epigraph on the south gate written by Kusuri; however, this inscription is not in place today. This bazaar was used as a wholesale market hall for meat, fruit and vegetables.

Bakırcılar çarşısi is the coppersmith bazaar of Gaziantep. This trade has existed in the region for over 500 years. The bazaar is part of the official culture route designed to help visitors discover the traditions and culture of the city.

Inns

Anatolia Inn The exact date of the inn's (caravanserai) construction is unknown, but it is estimated to have been built in the early 19th century. It is a two-storey building with two courtyards. It is said to have been built by Muhsinzade Hadji Mehmet Bey in 1892. The inn was repaired in 1985 and parts of the top floor were rebuilt.

Kürkçü Inn Classic Ottoman Inn in Boyacı built in 1890.

Old Wheat Inn The original building was constructed by Mustafa Ağa in 1640 to provide an income for the dervish lodge, but was completely destroyed in a fire. The exact construction date of the present building is unknown; however the architectural style suggests the 19th century.

Şire Inn The building is built on a rectangular plan and contains many motifs of classical Ottoman inn architecture. It was built with evenly cut stones and the pitched roof is covered by tiles.

Tobacco Inn This inn has no epigraph showing the dates of construction or renovation, but according to historical data, the estimated date of construction is the late 17th century. Ownership was passed to Hüseyin Ağa, son of Nur Ali Ağa, in the early 19th century.

Yüzükçü Inn The construction date of this inn is unknown. The epigraph on the main gate of the inn is dated 1800, but the building apparently had been built earlier and was repaired at this date. The first owners of the inn were Asiye, the daughter of Battal Bey and Emine Hatun, the daughter of Hadji Osman Bey.

Other

Zeugma is an ancient city which was established at the shallowest passable part of the river Euphrates, within the boundaries of the present-day Belkıs village in Gaziantep Province. Due to the strategic character of the region in terms of military and commerce since antiquity (Zeugma was the headquarters of an important Roman legion, the Legio IV Scythica, near the border with Parthia) the city has maintained its importance for centuries, also during the Byzantine period.

Gaziantep Castle, also known as Gala (حرفياً 'the castle'), located in the centre of the city displays the historic past and architectural style of the city. Although the history of castle is not fully known, as a result of the excavations conducted there, Bronze Age settlement layers are thought to exist under the section existing on the surface of the soil.

Pişirici Kastel, a "kastel" (fountain) which used to be a part of a bigger group of buildings, is thought to have been built in 1282. "Kastels" are water fountains built below ground, and they are structures peculiar to Gaziantep. They are places for ablution, prayer, washing and relaxation.

Old houses of Gaziantep, the traditional houses that are located in the old city: Eyüboğlu, Türktepe, Tepebaşı, Bostancı, Kozluca, Şehreküstü and Kale. They are made of locally found keymik rock and have an inner courtyard called the hayat, which is the focal point of the house.

Tahmis Coffee House, a coffee house that was built by Mustafa Ağa Bin Yusuf, a Turkmen[85] ağa and flag officer, in 1635–1638, in order to provide an income for the dervish lodge. The building suffered two big fires in 1901 and 1903.

المتاحف

- متحف غازيعنتپ الأثري

- متحف فسيفساء زيوگما، يضم قطع فسيفساء من زيوگما وأماكن أخرى، بإجمالي 1700 م².[citation needed] أفتتح للعامة في 9 سبتمبر 2011.

- متحف غازيعنتپ الأثري

- متحف مؤسسة نزل مولوي.

- متحف أمين گوگوش للطبخ.

أماكن تاريخية

- قلعة غازيعنتپ

- مسجد بوياشي

- مسجد شيرواني

- مسجد عميري

- مسجد الشيخ فتح الله

- مسجد نوري محمد پاشا

- مسجد أحمد شلبي

- مسجد تهتالي

- مسجد عبد ألوضولي

- مسجد علي نصر

- مسجد إيوپوگلو

- كنيسة كنديرلي

- قلعة پيشيرچي

- البيوت القديمة في غازيعنتپ

- مقهى تهميس

حديقة حيوان غازيعنتپ

التعليم

الثقافة العامة

الرياضة

| النادي | الرياضة | التأسيس | الرابطة | الملعب |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaziantepspor | كرة قدم | 1969 | Spor Toto Super League (Turkish Premier Division) | Gaziantep Kamil Ocak Stadium |

| Gaziantep Büyükşehir Belediyespor | كرة قدم | 1998 | Bank Asya 1. Lig (TFF First League) | Gaziantep Kamil Ocak Stadium |

| Gazikentspor | كرة قدم سيدات | 2006 | Women's First League | Gazikent Stadium |

| Gaziantep Büyükşehir Belediyespor (Played with sponsporship of Royal Halı since 2012) | كرة سلة | 2007 | Turkish Basketball League | Kamil Ocak Sports Hall |

| Gaziantep Polis Gücü SK Men's Hockey | هوكي | 2003 | Turkish Hockey Super League |

معرض الصور

Statue of dervishes inside a mevlevihane museum in Gaziantep

Statue of dervishes inside a mevlevihane museum in Gaziantep

Head of King Antiochus I of Commagene at the Gaziantep Museum of Archaeology

العلاقات الدولية

مدن شقيقة

غازيعنتپ على توأمة مع:

مشاهير المدينة

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ "Turkey (Registered Population): Provinces, Major Cities & Towns - Statistics & Maps on City Population". Citypopulation.de. 2011-12-31. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف ق ك ل م ن هـ و ي أأ Peirce, Leslie (2003). Morality Tales: Law and Gender in the Ottoman Court of Aintab. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520228924. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ "Statistics by Theme > National Accounts > Regional Accounts". www.turkstat.gov.tr. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ^ http://www.gaziantep.gov.tr/cumhurbaskanimiz-sn-erdogan-deprem-anindan-itibaren-devlet-olarak-tum-kurumlarimizla-sahadayiz-23-merkezicerik

- ^ أ ب Sarafean, Georg Avedis (1957). A Briefer History of Aintab A Concise History of the Cultural, Religious, Educational, Political, Industrial and Commercial Life of the Armenians of Aintab. Boston: Union of the Armenians of Aintab. p. 11. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

The population of Aintab in 1914, before the Armenian deportations started, was about 80,000;. The Armenians constituted a minority-30,000. These were divided as follows: Armenian protestants—4000; Catholics—400; and the rest, i.e., the bulk of Armenians belonging to the Armenian national apostolic church. Apostolic is a designation, chiefly because the Armenian church was founded by the apostles Thaddeus and Bartholemew. There were 2000 Kurds and a few hundred Cherkesse immigrants from the Caucasus regions, and the remainder of the 80,000; population consisted of Turks, who formed a majority group in the city.

- ^ ibn al-Qalanisi, H.A.R. Gibb, editor and translator, The Damascus chronicle of the Crusades, London 1932, p. 367.

- ^ Golius, Jacobus (1669). Muhammedis fil. Ketiri Ferganensis, qui vulgo Alfraganus dicitur, Elementa astronomica, Arabicè & Latinè. Cum notis ad res exoticas sive Orientales, quae in iis occurrunt. Opera Jacobi Golii. Amsterdam. p. 273. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ Saint-Martin, M. J. (1818). Mémoires historiques et géographiques sur l'Arménie: suivis du texte arménien de l'histoire des princes Orpélians, par Etienne Orpélian ... et de celui des géographies attribuées à Moyse de Khoren et au docteur Vartan, avec plusieurs autres pièces relatives à l'histoire d'Arménie: le tout accompagné d'une traduction française et de notes, Volume 1. Paris: Imprimerie Royale. p. 197. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ "Gaziantep Valilik". Gaziantep.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 2012-10-22. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ^ Chyet, Michael L. (2020-01-07). FERHENGA BIRÛSKÎ Kurmanji - English Dictionary Volume One: A - L (in الإنجليزية). Transnational Press London. ISBN 978-1-912997-04-6. Archived from the original on 2023-02-06. Retrieved 2021-02-13.

- ^ أ ب Abadie, Maurice (1959). Türk Verdünü, Gaziantep: Antep'in dört muhasarası. Gaziantep Kültür Derneği. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Diana Darke (1 May 2014). Eastern Turkey. Bradt Travel Guides. pp. 214–. ISBN 978-1-84162-490-7.

- ^ British Museum Collection

- ^ Anna Teresa Serventi (1957). "Una statuetta hiittita". Rivista Degli Studi Orientali (in الإيطالية). 32: 241–246. JSTOR 41922836.

Aintab, Gazi Antep in Turkish, about 80 km north-northeast from Aleppo and about 40 km from the Syrian-Turkish border, is commonly held to be the site of Antiochia ad Taurum

- ^ Brett, Michael (2001). The Rise of the Fatimids: The World of the Mediterranean and the Middle East in the Fourth Century of the Hijra, Tenth Century Ce. Brill. p. 225. ISBN 9004117415. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Güllü, Ramazan Erhan (2010). Antep Ermenileri sosyal kültürel ve siyasi hayat. IQ Kültür Sanat Yayıncılık. p. 43.

- ^ Theotokis, Georgios (2021). Bohemond of Taranto: Crusader and Conqueror. Pen and Sword. p. 101. ISBN 9781526744319. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Hovanissian, Richard G.; Payaslian, Simon, eds. (2008). Armenian Cilicia. Mazda Publishers. p. 33.

- ^ أ ب Le Strange, Guy (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Translated from the Works of the Medieval Arab Geographers. Houghton, Mifflin and Company. p. 387. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

Dimashki writes in the early part of the fourteenth century, 'lies north-east of Halab. It is a place with a strong castle. The people are Turkomans. There is a small river here, and gardens.' (Dim., 205.)

- ^ Ümit Kurt (13 April 2021). The Armenians of Aintab The Economics of Genocide in an Ottoman Province. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674259898. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "The Armenians of Aintab — Ümit Kurt". Archived from the original on 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- ^ American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, The Missionary Herald, January 1900, passim Archived 2023-02-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alice Shepard Riggs, Shepard of Aintab: Medical Missionary amongst Armenians, Turks, Kurds, and Arabs in Aintab, ISBN 1903656052

- ^ Ümit Kurt. The Armenians of Aintab: The Economics of Genocide in an Ottoman Province (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021).

- ^ Kévorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide a Complete History. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. pp. 605–610. ISBN 9780857719300.

- ^ Altınöz, İsmail (1999). Dulkadir Eyaleti'nin Kuruluşunda Antep Şehri (XVI. Yüzyıl). Gaziantep: Cumhuriyetin 75. Yılına Armağan. p. 146.

- ^ Şimşir, Bilâl, İngiliz Belgelerinde Atatürk, 1919-1938, Volume 3, Istanbul: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, p. 168.

- ^ Documents on British foreign policy, 1919-1939, London: H. M. Stationery Office, 1970, vol. 15, p. 155.

- ^ Bir 'mecbur adam'ın romanı, Radikal, 08.01.2010 (in تركية)

- ^ Ümit Kurt, Destruction of Aintab Armenians and Emergence of the New Wealthy Class: Plunder of Armenian Wealth in Aintab (1890s-1920s), Ph.D. Dissertation, Clark University, Worcester, MA, Strassler Center of Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 19 April 2016, quoted in Robert Fisk, "A beautiful mosque and the dark period of the Armenian genocide", The Independent, 15 October 2016

- ^ Kurt, Ümit (2019). "From Aintab to Gaziantep: The Reconstitution of an Elite on the Ottoman Periphery". The End of the Ottomans: The Genocide of 1915 and the Politics of Turkish Nationalism (in الإنجليزية). Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 318–319. ISBN 978-1-78831-241-7. "Official Turkish historiography claims that the Turkish–French war in Aintab was a heroic struggle for national independence, which earned the city glory and its grand title, ghazi (conqueror). Gaziantep's 'heroic epic' was in fact a struggle whose incentive was to wipe out the Armenian presence in the city for good. Its main motive was to ensure that the Armenians of Aintab would never be able to return to the city. Whether forcibly removed or through various administrative measures, the outcome of all of these 'struggles' rendered it impossible for Armenian repatriates to remain in their native cities, towns or villages. Hoping to make these people flee their homeland again, the brave national warriors continued to terrorise them. When the Armenians left Aintab for good in 1921–2, their leftover houses, fields, estates and other properties were sold at bargain prices."

- ^ "Patriotlar devrede". Milliyet (in التركية). 30 August 2013. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ "Bakan Kurum, Gaziantep'de 900 Bina Yıkıldı" (in التركية). Anadoludabugun.com. 2023-02-08.

- ^ "Bakanlık duyurdu: Şehir şehir hasar tespit durumları" (in التركية). Diken.com.tr. 2023-02-14.

- ^ "Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution". Nature Scientific Data. DOI:10.1038/sdata.2018.214.

- ^ Kalelioğlu, Ejder (1966). "Gaziantep Platosu ve Çevresinin İklimi" [Gaziantep Plateau and the Climate of Its Vicinity] (PDF). Ankara University Language and History-Geography Department Journal of Research (1): 297–320. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ أ ب "İllerimize Ait Genel İstatistik Verileri" (in Turkish). Meteoroloji Genel Müdürlüğü. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Resmi İstatistikler: İllerimize Ait Mevism Normalleri (1991–2020)" (in التركية). Turkish State Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020: Gaziantep" (CSV). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ "Gaziantep - Weather data by month". meteomanz. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ "Gaziantep Seçim Sonuçları - 31 Mart Gaziantep Yerel Seçim Sonuçları". secim.haberler.com (in التركية). Archived from the original on 2020-06-04. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ^ https://secim.hurriyet.com.tr/31-mart-2024-yerel-secimleri/gaziantep-ili-yerel-secim-sonuclari/

- ^ "Statistics" (in التركية). Gaziantep Chamber of Industry. Archived from the original on 2009-01-31.

- ^ أ ب Ayaydın, Eşber (10 June 2022). "Gaziantep ve Şanlıurfa arasında ismi paylaşılamayan lezzet: Fıstık". Anadolu Agency. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ Syrians' New Ardor for a Turkey Looking Eastward Archived 2017-05-12 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, July 24, 2010

- ^ أ ب ت Yoon, John (7 February 2023). "Gaziantep, a city millenniums old, has long been a hub for trade and cultures". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

Gaziantep's population is a mixture of communities, including the ethnic Turks who make up the majority, Professor Casana said. Since the Syrian civil war began in 2011, Gaziantep has become home to about 470,000 Syrian refugees, according to the United Nations. But even before the war, busloads of Syrians were crossing the border almost daily to shop in Gaziantep as Turkey pushed stronger economic ties with Syria. Syrians, who now make up more than 20 percent of the population, have transformed Gaziantep, investing and bringing business skills and cheap labor. Many of the city's textile factories were built by Syrian migrants. Turkish and Syrian companies share buildings and workers. Hundreds of cafes, restaurants and pastry shops there cater to Syrians. There is also a large Kurdish community, mostly concentrated in certain towns and neighborhoods, Professor Casana said. Kurds have been involved in a long-running conflict with the Turkish government. The Islamic State, which has fought Kurds in Syria, has also targeted the Kurds in Gaziantep, including the 2014 bombing of a Kurdish wedding, an attack that killed more than 50 people.

- ^ أ ب Kahvecioğlu, Ayşe (28 August 2016). "5 yıl sonrası için uyarılar". Milliyet. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ أ ب Büsching, Anton Friedrich (1787). A. F. Büschings grosse Erdbeschreibung: Asia. - Abth. 1. Brno. p. 447. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

Alle Christen, die gegen Norden von Haleb wohnen, sind Armenier. Fast in allen Dörfern und Flecken zwischen Haleb und Aintab wird türkisch, aber kein arabisch gesprochen. In der Gegend von Aintab halten sich die turkomanischen Stämme(...)

- ^ Aucher-Eloy, Remi (1843). Relations de voyages en Orient de 1830 à 1838 ... revues et annotées par M. le comte Jaubert, Volume 1. Paris: Libraire Encyclopédique de Roret. p. 87. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

Aintab peut avoir 15,000 haibtants: Turcs, Arméniens, schismatiques et quelques Grecs.

- ^ Konversations Lexikon. Leipzig: Bibliographisches Institut. 1885. p. 242.

Aïntab, Stadt im nördlichen Syrien, 104 km nördlich von Aleppo, am Flusse Sadschur, mit Baumwoll Seide und Lederindustrie, reichem Obstbau und etwa 20,000 meist turkmen. Einwohnern (darunter ca. 5000 Armenier und 1200 Brotestanten). A. ist Hauptstation der nordamerikanisch-evangelischen Mission.

- ^ Reclus, Elisée (1895). The Earth And Its Inhabitants. Asia Vol. IV. South-western Asia. New York: D. Appleton and Company. p. 232. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

Aintab, which is chiefly inhabited by Turkomans,

- ^ أ ب Farley, James Lewis (1862). The Resources of Turkey Considered with Especial Reference to the Profitable Investment of Capital in the Ottoman Empire. London: Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts. pp. 243–244. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

The population amounts to 27,000 souls; of whom 18,000 are Turks, 8,500 Armenians, and 500 Jews. Turkish is the language universally used; the Armenians having completely forgotten ther mother tongue, though in the books which they make use of they employ the Armenian characters, from their superior simplicity to the Arabic. The inhabitants of the country are chiefly Turks, who claim their property in the land as far as back as the time of the old Seljoukian dynasty. (...) Turks residing at Aintab, who form the wealthy portion of its Mussulman population(...)

- ^

Hogarth, David George (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 1 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 441.

Hogarth, David George (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 1 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 441. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Le Coq de Kerland, Robert (1907). Un chemin de fer en Asie Mineure. Paris: Librairie Nouvelle de Droit et de Jurisprudence. p. 71.

Après avoir suivi la route des caravanes vers Sam, la ligne atteint la ville de Aintab habitée surtout par les Turcomans.

- ^ Çay, Mustafa Murat (13 March 2019). "AN ASSESSMENT OF A. GESAR'S BOOK: 'AINTAB'S STRUGGLE FOR EXISTENCE AND THE ATTITUDE AND BEHAVIOR OF ANTEP ARMENIANS DURING THE INVASIONS' -THE ANATOMY OF A PARADOX". International Journal of Eurasia Social Sciences. 10 (35): 282–312. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ أ ب Vaux, Bert (2000). "Notes on the Armenian Dialect of Ayntab". Annual of Armenian Linguistics (20): 55–82. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Pococke, Richard (1745). A DESCRIPTION OF THE EAST, AND Some Other COUNTRIES.: OBSERVATIONS on PALAESTINE or the HOLY LAND, SYRIA, MESOPOTAMIA, CYPRUS, and CANDIA, Volume 2. London: W. Bowyer. p. 155. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ de La Harpe, Jean François (1801). Abrege de l'histoire generale des voyages. Paris: chez Moutardier. p. 362. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Malte-Brun, Conrad (1822). Universal Geography, Or, a Description of All the Parts of the World, on a New Plan: Asia (2 ed.). Edinburgh: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. p. 134. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ Besalel, Yusuf. "Gaziantep ve Van Yahudileri". Şalom Gazetesi (in التركية). Archived from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ أ ب Altaras, Nesi (31 May 2019). "Gaziantep Yahudileri ve Sinagogu Hatırlanmalı". Avlaremoz. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Coşkun, Bezen Balamir; Yıldız Nielsen, Selin (30 September 2018). Encounters in the Turkey-Syria Borderland. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 9781527516922. Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ Aksoy, Metin; Taşkin, Faruk (Summer 2015). "Antep Amerikan Hastanesi ve Bölge Halkı Üzerindeki Etkisi (1880-1920)" [AINTAB AMERICAN HOSPITAL AND ITS EFFECT ON THE REGION PEOPLE (1880-1920)]. Turkish Studies - International Periodical for the Languages, Literature and History of Turkish or Turkic (in التركية). 10 (9): 23–42. doi:10.7827/TurkishStudies.8598.

- ^ Sevinç, Necdet (1997). Gaziantep'te Türk boyları. p. 135.

Gaziantep yöresinde Özbekler'in varlığını biliyoruz. Hatta yakın zamanlara kadar, bugünkü Ticaret Sarayı'nın yerinde Özbekler'i himâye etmek amacıyla kurulduğu anlaşılan bir Nakşibendî Tekkesi vardı.

- ^ Çağlar, Nafi (21 September 2019). Kızık Boyu. Vol. 2. Yalın Yayıncılık. p. 21.

Şehir içinde de çok miktarda Özbek vardır.

- ^ "Five great synagogues in Turkey – Jewish Cultural Heritage". eSefarad. 6 February 2018. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ Umumî Nüfus Tahriri. İstatistik Umum Müdürlüğü. 1927. pp. 237–238. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ "Lezzet Haritası". Anadolu Agency. Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ "Gaziantep cuisine added to UNESCO list". Hürriyet Daily News (in الإنجليزية). 13 December 2015. Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ "Gaziantep". en.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 27 January 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ "Publication of an application pursuant to Article 50(2)(a) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs". European Commission. 2009-10-07. Archived from the original on 2013-12-20. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- ^ Barkley, Henry C. (1891). A Ride through Asia Minor and Armenia. London: William Clowes and Sons Limited. p. 185.

All the villages ahead of us were full of good things, and the padishah himself would do well to visit Aintab, just to taste the rich food to be found there.

- ^ "Sözlük". Gaziantep Ağzı. Şehitkamil Municipality. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Taşçıyan, Sonya. "Antep-Yemekler". Houshamadyan. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ "Yapma Kızartması (Gaziantep)". Nefis Yemek Tarifleri (in التركية). 7 April 2017. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ "Gaziantep Usulü Malhıtalı Köfte". nefis yemek tarifleri. 22 November 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "Antep Usulü Kabaklama". nefis yemek tarifleri. 22 June 2016. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ Karahan, Leylâ (1996). Anadolu ağızlarının sınıflandırılması. Türk Dil Kurumu. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Karahan, Leylâ (Winter 2013). "GRAMATİKAL ÖLÇÜTLERLE BELİRLENEN TÜRKİYE TÜRKÇESİ AĞIZ GRUPLARINDA LEKSİK VERİLERİN ANLAMLILIĞI ÜZERİNE BİR ARAŞTIRMA". Diyalektolog (7): 1–9. Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Kurt, Ümit (2021). The Armenians of Aintab: The Economics of Genocide in an Ottoman Province. Harvard University Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780674259898. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ "Antep Ağzını Unutturmayacağız". Gaziantep Haberler (in التركية). Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Boncuk, Mehmet. "Dünyanın en meşhur yerel tiyatrosu". Sabah (in التركية). Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ "Zeugma Mosaic Museum: Strolling Along A Neighbourhood of Ancient Treasures". 11 June 2013. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ "the Zeugma Mosaic Museum, Turkey". 2015-03-14. Archived from the original on 2017-12-23. Retrieved 2017-12-22.

- ^ Güler, Mustafa (2016). "ANTEP (AYINTAB) MEVLEVÎHÂNESİ'NİN MİMARİ OLARAK İNCELENMESİ VE DEĞERLENDİRİLMESİ". İstem. 27 (14): 43–77. Archived from the original on 2021-07-27. Retrieved 2021-07-27.

- ^ "Cities Twinned with Duisburg". Duisburg. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ^ "List of Twin Towns in the Ruhr District" (PDF). © 2009 Twins2010.com. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher=

وصلات خارجية

- (إنگليزية) Discover Gaziantep

- (إنگليزية) Gaziantep Photos

- (إنگليزية) Over 1500 pictures of the city, monuments, museums - without advertising

- (إنگليزية) About Coffee house culture in Gaziantep

- (لغة تركية) Gaziantep City Guide

- (لغة تركية) Gaziantep University

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 الإيطالية-language sources (it)

- Articles with تركية-language sources (tr)

- CS1 التركية-language sources (tr)

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using infobox settlement with unknown parameters

- Articles containing explicitly cited عربية-language text

- Articles containing فارسية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2015

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2023

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2025

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2021

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2012

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- مقاطعات محافظة غازيعنتپ

- غازيعنتپ

- مدن تركيا

- مواقع يونانية قديمة في تركيا

- مواقع رومانية في تركيا

- محافظة غازيعنتپ

- الأقاليم السورية الشمالية

- مناطق عربية تخضع لنفوذ أجنبي

- أماكن مأهولة تأسست في الألفية 4 ق.م.