فرانز يوزف الأول من النمسا

| Franz Joseph I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

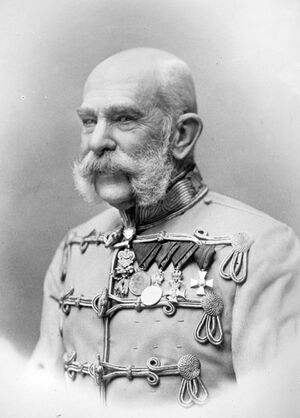

Franz Joseph in 1903 | |||||

| Emperor of Austria King of Hungary (more…) | |||||

| العهد | 2 December 1848 – 21 November 1916 | ||||

| Coronation | 8 June 1867 Matthias Church (as King of Hungary) | ||||

| سبقه | Ferdinand I & V | ||||

| تبعه | Charles I, III & IV | ||||

| King of Lombardy-Venetia | |||||

| العهد | 2 December 1848 – 12 October 1866 | ||||

| سبقه | Ferdinand I | ||||

| تبعه | Annexation to Italy | ||||

| Head of the Präsidialmacht Austria | |||||

| In office 1 May 1850 – 24 August 1866 | |||||

| سبقه | Ferdinand I | ||||

| خلـَفه | Wilhelm I (as Head of the North German Confederation) | ||||

| وُلِد | 18 أغسطس 1830 Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna, Austrian Empire | ||||

| توفي | 21 نوفمبر 1916 (aged 86) Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna, Austria-Hungary | ||||

| الدفن | |||||

| الزوج | |||||

| الأنجال | |||||

| |||||

| البيت | Habsburg-Lorraine | ||||

| الأب | Archduke Franz Karl of Austria | ||||

| الأم | Princess Sophie of Bavaria | ||||

| الديانة | Catholic Church | ||||

| التوقيع | |||||

فرانز يوزف الأول من النمسا Franz Joseph I of Austria (و.1830 –ت. 1916م). الحاكم المعمّر للمملكة المزدوجة النمسا والمجر في أوائل الحرب العالمية الأولى. حكم فرانسيس جوزيف إمبراطور النمسا لمدة 68 عامًا، وكانت شعبيته وقوته العسكرية السبب في تماسك عناصر المملكة المزدوجة المتباينة. وحينما اغتيل وريثه وابن أخيه الأرشيدوق فرانسيس فرديناند عام 1914م، أعلن الحرب على صربيا وهذا ما أدى إلى قيام الحرب العالمية الأولى.

أصبح فرانسيس جوزيف إمبراطورًا للنمسا عام 1848م، وهو عام ثورات وطنية. وكان عضوًا في العائلة الحاكمة القديمة في هابسبورگ. وخلال حكمه الطويل ازدهرت النمسا بالرغم من معاناتها من عدة هزائم حربية. وفي الحرب ضد سردينيا، وفرنسا عام 1859م، فقدت النمسا مقاطعة لومباردي. مملكة. وهزمت بروسيا سردينيا وثلاث مقاطعات ألمانية أصغر منها في حرب الأسابيع السبعة.

وتبنى فرانسيس جوزيف سياسات داخلية أكثر ليبرالية مانحًا المجريين حقوقًا متساوية، وحصل جوزيف على لقب إضافي وهو ملك المجر عام 1867م.

قتل رودلف الابن الوحيد لفرانسيس جوزيف نفسه عام 1889م، وقتل ثائر إيطالي إليزابيث زوجة فرانسيس جوزيف. وتولى ابن أخيه تشارلز الأول الحكم بعده إمبراطوراً.

النشأة

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ثورات 1848

During the Revolutions of 1848, the Austrian Chancellor Prince Klemens von Metternich resigned (March–April 1848). The young archduke, who (it was widely expected) would soon succeed his uncle on the throne, was appointed Governor of Bohemia on 6 April 1848, but never took up the post. Sent instead to the front in Italy, he joined Field Marshal Radetzky on campaign on 29 April, receiving his baptism of fire on 5 May at Santa Lucia.

By all accounts, he handled his first military experience calmly and with dignity. Around the same time, the imperial family was fleeing revolutionary Vienna for the calmer setting of Innsbruck, in Tyrol. Called back from Italy, the archduke joined the rest of his family at Innsbruck by mid-June. It was here that Franz Joseph first met his cousin and eventual future bride, Elisabeth, then a girl of 10, but apparently the meeting made little impression.[1]

Following Austria's victory over the Italians at Custoza in late July 1848, the court felt it safe to return to Vienna, and Franz Joseph travelled with them. But within a few weeks, Vienna again appeared unsafe, and in September, the court left once more, this time for Olmütz in Moravia. By now, Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz, an influential military commander in Bohemia, was determined to see the young archduke soon put on the throne. It was thought that a new ruler would not be bound by the oaths to respect constitutional government to which Ferdinand had been forced to agree, and that it was necessary to find a young, energetic emperor to replace the kindly but mentally unfit Ferdinand.[2]

By the abdication of his uncle Ferdinand and the renunciation of his father (the mild-mannered Franz Karl), Franz Joseph succeeded as Emperor of Austria at Olmütz on 2 December 1848. At this time, he first became known by his second as well as his first Christian name. The name "Franz Joseph" was chosen to bring back memories of the new Emperor's great-granduncle, Emperor Joseph II (Holy Roman Emperor from 1765 to 1790), remembered as a modernising reformer.[3]

Under the guidance of the new prime minister, Prince Felix of Schwarzenberg, the new emperor at first pursued a cautious course, granting a constitution in March 1849. At the same time, a military campaign was necessary against the Hungarians, who had rebelled against Habsburg central authority in the name of their ancient constitution. Franz Joseph was also almost immediately faced with a renewal of the fighting in Italy, with King Charles Albert of Sardinia taking advantage of setbacks in Hungary to resume the war in March 1849.

However, the military tide began to turn swiftly in favor of Franz Joseph and the Austrian whitecoats. Almost immediately, Charles Albert was decisively beaten by Radetzky at Novara and forced to sue for peace, as well as to renounce his throne.

الثورة في المجر

Unlike other Habsburg ruled areas, the Kingdom of Hungary had an old historic constitution,[4] which limited the power of the crown and had greatly increased the authority of the parliament since the 13th century. The Hungarian reform laws (April laws) were based on the 12 points that established the fundaments of modern civil and political rights, economic and societal reforms in the Kingdom of Hungary.[5] The crucial turning point of the Hungarian events were the April laws which was ratified by his uncle King Ferdinand, however the new young Austrian monarch Francis Joseph arbitrarily "revoked" the laws without any legal competence. The monarchs had no right to revoke Hungarian parliamentary laws which were already signed. This unconstitutional act irreversibly escalated the conflict between the Hungarian parliament and Francis Joseph. The Austrian Stadion Constitution was accepted by the Imperial Diet of Austria, where Hungary had no representation, and which traditionally had no legislative power in the territory of Kingdom of Hungary; despite this, it also tried to abolish the Diet of Hungary (which existed as the supreme legislative power in Hungary since the late 12th century.)[6]

The new Austrian constitution also went against the historical constitution of Hungary, and even tried to nullify it.[7] Even the territorial integrity of the country was in danger: On 7 March 1849, an imperial proclamation was issued in the name of the Emperor Francis Joseph, according to the new proclamation, the territory of Kingdom of Hungary would be carved up and administered by five military districts, while the Principality of Transylvania would be reestablished.[8] These events represented a clear and obvious existential threat for the Hungarian state. The new constrained Stadion Constitution of Austria, the revocation of the April laws and the Austrian military campaign against Kingdom of Hungary resulted in the fall of the pacifist Batthyány government (which sought agreement with the court) and led to the sudden emergence of Lajos Kossuth's followers in the Hungarian parliament, who demanded the full independence of Hungary. The Austrian military intervention in the Kingdom of Hungary resulted in strong anti-Habsburg sentiment among Hungarians, thus the events in Hungary grew into a war for total independence from the Habsburg dynasty.

المشاكل الدستورية والشرعية في المجر

On 7 December 1848, the Diet of Hungary formally refused to acknowledge the title of the new king, "as without the knowledge and consent of the diet no one could sit on the Hungarian throne", and called the nation to arms.[8] While in most Western European countries (like France and the United Kingdom) the monarch's reign began immediately upon the death of their predecessor, in Hungary the coronation was indispensable; if it were not properly executed, the kingdom remained "orphaned".

Even during the long personal union between the Kingdom of Hungary and other Habsburg ruled areas, the Habsburg monarchs had to be crowned as King of Hungary in order to promulgate laws there or exercise royal prerogatives in the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary.[9][10][11] From a legal point of view, according to the coronation oath, a crowned Hungarian king could not relinquish the Hungarian throne during his life; if the king was alive and unable to do his duty as ruler, a governor (or regent, as they would be called in English) had to assume the royal duties. Constitutionally, Franz Joseph's uncle Ferdinand was still the legal king of Hungary. If there was no possibility to inherit the throne automatically due to the death of the predecessor king (since King Ferdinand was still alive), but the monarch wanted to relinquish his throne and appoint another king before his death, technically only one legal solution remained: the parliament had the power to dethrone the king and elect a new king. Due to the legal and military tensions, the Hungarian parliament did not grant Franz Joseph that favour. This event gave to the revolt an excuse of legality. Actually, from this time until the collapse of the revolution, Lajos Kossuth (as elected regent-president) became the de facto and de jure ruler of Hungary.[8]

الصعوبات العسكرية في المجر

While the revolutions in the Austrian territories had been suppressed by 1849 in Hungary, the situation was more severe and Austrian defeat seemed imminent. Sensing a need to secure his right to rule, Franz Joseph sought help from Russia, requesting the intervention of Tsar Nicholas I, in order "to prevent the Hungarian insurrection developing into a European calamity".[12] For the Russian military support, Franz Joseph kissed the hand of the tsar in Warsaw on 21 May 1849.[13] Tsar Nicholas supported Franz Joseph in the name of the Holy Alliance,[14] and sent a 200,000 strong army with 80,000 auxiliary forces. Finally, the joint army of Russian and Austrian forces defeated the Hungarian forces. After the restoration of Habsburg power, Hungary was placed under brutal martial law.[15]

With order now restored throughout his empire, Franz Joseph felt free to renege on the constitutional concessions he had made, especially as the Austrian parliament meeting at Kremsier had behaved—in the young Emperor's eyes—abominably. The 1849 constitution was suspended, and a policy of absolutist centralism was established, guided by the Minister of the Interior, Alexander Bach.[16]

محاولة الاغتيال في 1853

On 18 February 1853, Franz Joseph survived an assassination attempt by Hungarian nationalist János Libényi.[17] The emperor was taking a stroll with one of his officers, Count Maximilian Karl Lamoral O'Donnell, on a city bastion, when Libényi approached him. He immediately struck the emperor from behind with a knife straight at the neck. Franz Joseph almost always wore a uniform, which had a high collar that almost completely enclosed the neck. The collars of uniforms at that time were made from very sturdy material, precisely to counter this kind of attack. Even though the Emperor was wounded and bleeding, the collar saved his life. Count O'Donnell struck Libényi down with his sabre.[17]

O'Donnell, hitherto a Count only by virtue of his Irish nobility,[18] was made a Count of the Habsburg monarchy (Reichsgraf). Another witness who happened to be nearby, the butcher Joseph Ettenreich, swiftly overpowered Libényi. For his deed he was later elevated to the nobility by the emperor and became Joseph von Ettenreich. Libényi was subsequently put on trial and condemned to death for attempted regicide. He was executed on the Simmeringer Heide.[19]

After this unsuccessful attack, the emperor's brother Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian called upon Europe's royal families for donations to construct a new church on the site of the attack. The church was to be a votive offering for the survival of the emperor. It is located on Ringstraße in the district of Alsergrund close to the University of Vienna, and is known as the Votivkirche.[17] The survival of Franz Joseph was also commemorated in Prague by erecting a new statue of St. Francis of Assisi, the patron saint of the emperor, on Charles Bridge. It was donated by Count Franz Anton von Kolowrat-Liebsteinsky, the first minister-president of the Austrian Empire.[20]

Consolidation of domestic policy

Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867

The 1850s witnessed several failures of Austrian external policy: the Crimean War, the dissolution of its alliance with Russia, and defeat in the Second Italian War of Independence. The setbacks continued in the 1860s with defeat in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, which resulted in the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867.[21]

المسألة البوهيمية

السياسة الخارجية

المسألة الألمانية

عصبة الأباطرة الثلاثة

Titles, styles, honours and arms

| Styles of Franz Joseph I of Austria and Hungary | |

|---|---|

| |

| أسلوب الإشارة | His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty |

| أسلوب المخاطبة | Your Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty |

| Monarchical styles of Franz Joseph I of Austria | |

|---|---|

| |

| أسلوب الإشارة | His Imperial and Royal Majesty |

| أسلوب المخاطبة | Your Imperial and Royal Majesty |

| Monarchical styles of Ferenc József I of Hungary | |

|---|---|

| |

| أسلوب الإشارة | His Apostolic Majesty |

| أسلوب المخاطبة | Your Apostolic Majesty |

Name

Franz Joseph's names in the languages of his empire included:

Titles and styles

- 18 August 1830 – 2 December 1848: His Imperial and Royal Highness Archduke and Prince Francis Joseph of Austria, Prince of Hungary, Bohemia and Croatia[22]

- 2 December 1848 – 21 November 1916: His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty The Emperor of Austria, Apostolic King of Hungary

| Silver 20 kreuzer coin of Franz Joseph, struck 1868 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Obverse: (Latin) FRANC[ISCVS] JOS[EPHVS] I D[EI] G[RATIA] AVSTRIAE IMPERATOR, or in English, "Francis Joseph I, by the Grace of God Emperor of Austria" The Vienna mint continues to restrike gold corona and ducat coins which depict the emperor. | Reverse: (Latin) HVNGAR[IAE] BOHEM[IAE] GAL[ICIAE] LOD[OMERIAE] ILL[YRIAE] REX A[RCHIDVX] A[VSTRIAE] 1868, or in English, continuing from the obverse, "King of Hungary, of Bohemia, of Galicia, of Lodomeria, of Illyria, Archduke of Austria 1868." |

العدد

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Duchess Elisabeth in Bavaria (24 Dec 1837 - 10 Sep 1898; married on 24 April 1854 in St. Augustine's Church, Vienna) | |||

| Sophie Friederike Dorothea Maria Josepha | 5 March 1855 | 29 May 1857 | died in childhood |

| Gisela Louise Marie | 15 July 1856 | 27 July 1932 | married, 1873 her second cousin, Prince Leopold of Bavaria; had issue |

| Rudolf Francis Charles Joseph | 21 August 1858 | 30 January 1889 | died in the Mayerling Incident married, 1881, Princess Stephanie of Belgium; had issue |

| Marie Valerie Mathilde Amalie | 22 April 1868 | 6 September 1924 | married, 1890 her second cousin, Archduke Franz Salvator, Prince of Tuscany; had issue |

معرض الصور

Franz Joseph and his great-great-nephew Archduke Otto Emperor Franz Joseph being greeted, circa 1910

السلف

الأنواط والأوسمة

| Monarchical styles of Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary | |

|---|---|

| |

| أسلوب الإشارة | His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty |

| أسلوب المخاطبة | Your Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty |

| أسلوب بديل | My Lord |

انظر أيضا

ملاحظات

- ^ Murad 1968, p. 33.

- ^ Murad 1968, p. 8.

- ^ Murad 1968, p. 6.

- ^ Robert Young (1995). Secession of Quebec and the Future of Canada. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-7735-6547-0.

the Hungarian constitution was restored.

- ^ Ferenc Szakály (1980). Hungary and Eastern Europe: Research Report Volume 182 of Studia historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. Akadémiai Kiadó. p. 178. ISBN 978-963-05-2595-4.

- ^ Július Bartl (2002). Slovak History: Chronology & Lexicon, G – Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-86516-444-4.

- ^ Hungarian statesmen of destiny, 1860–1960, Volume 58 of Atlantic studies on society in change, Volume 262 of East European monographs. Social Sciences Monograph. 1989. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-88033-159-3.

- ^ أ ب ت This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Phillips, Walter Alison (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 13 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 917–918.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Yonge, Charlotte (1867). "The Crown of St. Stephen". A Book of Golden Deeds Of all Times and all Lands. London, Glasgow and Bombay: Blackie and Son. Retrieved 21 أغسطس 2008.

- ^ Nemes, Paul (10 يناير 2000). "Central Europe Review – Hungary: The Holy Crown". Archived from the original on 17 مايو 2019. Retrieved 26 سبتمبر 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ An account of this service, written by Count Miklos Banffy, a witness, may be read at The Last Habsburg Coronation: Budapest, 1916. From Theodore's Royalty and Monarchy Website.

- ^ Rothenburg, G. The Army of Francis Joseph. West Lafayette, Purdue University Press, 1976. p. 35.

- ^ Paul Lendvai (2021). The Hungarians A Thousand Years of Victory in Defeat. Princeton University Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-691-20027-9.

- ^ Eric Roman: Austria-Hungary & the Successor States: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present p. 67, Publisher: Infobase Publishing, 2003 ISBN 978-0-8160-7469-3

- ^ The Making of the West: Volume C, Lynn Hunt, pp. 683–684

- ^ Murad 1968, p. 41.

- ^ أ ب ت Murad 1968, p. 42.

- ^ As a descendant of the Irish noble dynasty O'Donnell of Tyrconnell: O'Domhnaill Abu – O'Donnell Clan Newsletter no. 7, Spring 1987. ISSN 0790-7389

- ^ Decker, Wolfgang. "Kleingartenanlage Simmeringer Haide". www.simmeringerhaide.at. Retrieved 4 أكتوبر 2018.

- ^ "Statuary of St. Francis Seraph". Královská cesta. Archived from the original on 27 فبراير 2021. Retrieved 17 أغسطس 2019.

- ^ Murad 1968, p. 169.

- ^ Kaiser Joseph II. harmonische Wahlkapitulation mit allen den vorhergehenden Wahlkapitulationen der vorigen Kaiser und Könige. Since 1780 official title used for princes ("zu Ungarn, Böhmen, Dalmatien, Kroatien, Slawonien, Königlicher Erbprinz")

المصادر

قراءات إضافية

- Beller, Steven. Francis Joseph. Profiles in power. London: Longman, 1996.

- Bled, Jean-Paul. Franz Joseph. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

- Cunliffe-Owen, Marguerite. Keystone of Empire: Francis Joseph of Austria. New York: Harper, 1903.

- Gerö, András. Emperor Francis Joseph: King of the Hungarians. Boulder, Colo.: Social Science Monographs, 2001.

- Palmer, Alan. Twilight of the Habsburgs: The Life and Times of Emperor Francis Joseph. New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995.

- Redlich, Joseph. Emperor Francis Joseph Of Austria. New York: Macmillan, 1929.

- Van der Kiste, John. Emperor Francis Joseph: Life, Death and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Stroud, England: Sutton, 2005.

فرانز يوزف الأول من النمسا وُلِد: 18 أغسطس 1830 توفي: 21 نوفمبر 1916

| ||

| ألقاب ملكية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه Charles I |

امبراطور النمسا 1848-1916 |

تبعه Ferdinand I |

| سبقه Charles IV |

ملك المجر 1867-1916 |

تبعه Ferdinand I |

| سبقه William I of Prussia as President of the North German Confederation |

President of the German Confederation 1849-1866 |

تبعه Ferdinand I |

وصلات خارجية

- Biography at WorldWar1.com

- Details at Regiments.org

- Genealogy

- Mayerling tragedy

- Miklós Horthy reflects on Franz Josef

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Wikipedia articles incorporating text from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Use dmy dates from April 2023

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- Articles with hAudio microformats

- Articles containing بوسنية-language text

- Articles containing كرواتية-language text

- Articles containing تشيكية-language text

- Articles containing مجرية-language text

- Articles containing إيطالية-language text

- Articles containing پولندية-language text

- Articles containing رومانية-language text

- Articles containing صربية-language text

- Articles containing سلوڤاكية-language text

- Articles containing Slovene-language text

- Articles containing أوكرانية-language text

- مواليد 1830

- وفيات 1916

- أباطرة النمسا

- 19th-century monarchs in Europe

- Austrian Field Marshals

- أمراء بوهيميون

- Grand Masters of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary

- Grand Masters of the Order of the Golden Fleece

- بيت هابسبورگ-لورين

- ملوك المجر

- حكام ترانسلڤانيا

- ملوك كرواتيا

- فرسان الوبر الذهبي

- Knights of the Order of the Norwegian Lion

- Military Order of Maria Theresa recipients

- أشخاص من ڤيينا

- أشخاص من العصر الإدواردي

- أشخاص في ثورات 1848

- أشخاص من العصر الڤكتوري

- Recipients of the Military Order of Max Joseph

- حائزو مرتبة النسر الأسود

- حائزو مرتبة النسر الأحمر

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (military class)

- ملوك كاثوليك

- Recipients of the Order of Prince Danilo I

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Prince Danilo I of Montenegro

- Degraded Extra Knights Companion of the Garter

- Annulled Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order

- Annulled Recipients of the Royal Victorian Chain

- Knights Grand Cross of the Military William Order