فرا أنجليكو

| فرا أنجليكو Fra Angelico | |

|---|---|

Posthumous portrait of Fra Angelico by لوكا سنيورلي، تفصيلة من جصية أعمال المسيح الدجال (ح.1501) في كاتدرائية اورڤييتو، إيطاليا. | |

| اسم الميلاد | Guido di Pietro |

| وُلِد | ح. 1395 Rupecanina, Mugello region, جمهورية فلورنسا |

| توفي | 18 فبراير 1455 (عن عمر 59) روما, الدويلات الپاپوية |

| الجنسية | فلورنسي |

| المجال | رسم, جصيات |

| الحركة | النهضة الإيطالية المبكرة |

| Works | Annunciation of Cortona, Fiesole Altarpiece, San Marco Altarpiece, Deposition of Christ، المصلى النيكولي |

| الراعون | كوزيمو ده مديتشي، الپاپا يوجين الرابع، الپاپا نيكولاس الخامس |

| Blessed John of Fiesole, O.P. | |

|---|---|

مكرّم في | الكنيسة الكاثوليكية (نظام الدومنيكان) |

| Beatified | 3 أكتوبر 1982, مدينة الڤاتيكان by الپاپا يوحنا پولس الثاني |

| عيده | 18 فبراير |

| يرعى | الفنانون |

فرا أنجليكو Fra Angelico (وُلِد گويدو دي پييترو Guido di Pietro؛ ح. 1395[1] – 18 فبراير 1455) كان رساماً من النهضة الإيطالية المبكرة وصفه ڤاساري في كتابه حيوات الفنانين بامتلاكه "موهبة نادرة وكاملة".[2]

السيرة

ظل فرا أنجيلكو وسط هذه الأساليب الجديدة المثيرة يسير في هدوء على طريقته هو طريقة العصور الوسطى. وكان مولده في قرية تسكانية وسمي جيدو دي بيترو، ثم وفد إلى فلورنس وهو شاب، ودرس فن التصوير، وأكبر الظن أنه درسه مع لورندسو وموناكو. وسرعان ما نضجت موهبته الفنية، وهيئت له جميع السبل التي تمكنه من أن يشغل مكاناً طيباً مريحاً في العالم، ولكن حب السلام وأمله في النجاة حملاه على أن يلتحق بطائفة الرهبان الدمنيك (1407). وظل فرا جوڤاني (الأخ جوفني)- وهو الاسم الذي اطلق عليه في هذه الفترة-يتدرب على نظام الرهبنة زمناً طويلاً في عدة مدن مختلفة، استقر بعدها في دير سان دمنيكو SanDominico ببلدة فيسولي Fiesole(1418)، حيث شرع وسط عادته التي حباه احتجاجه وخمول ذكره يزين المخطوطات ويرسم صور الكنائس وجماعات الإخوان الدينية. وحدث في عام 1436 أن نقل رهبان سان دمنيكو إلى دير سان ماركو الجديد الذي شاده ميكلتسو بأمر كوزيمو ومن ماله. ورسم جوڤاني في التسع السنين التالية نحو خمسين صورة بالجص على جدران كنيسة الدير-تشمل بيت القسيسين، ومكان نومهم، ومطعمهم، وموضع راحتهم، وطرقات الدير المقنطرة المسقوفة، وصوامع الرهبان. وكان في خلال هذه المدة يقوم بالشعائر الدينية في تواضع وخشوع حملا زملاءه الرهبان على أن يسموه »الأخ الملاك« فرا أنجيلكو Fra Angelico. وقد بلغ من حلمه أن أحداً من الناس لم يره غاضباً قط، وان أحداً لم يفلح قط في أن يغضبه. وكان في وسع تومس أكمبس Thomas à Kempis أن يجد الصورة التي رسمها لتمثيل محاكاة المسيح قد تحققت إلى أكمل حد فيه إذا استثنينا من ذلك التعميم زلة واحدة لا يستطيع الإنسان معها أن يحاجز نفسه عن الابتسام: ذلك أن الراهب الملاك الدمنيكي لم يستطع أن يقاوم نزعة من نزعاته فوضع في صورة من صور يوم الحساب عدداً قليلا من الرهبان الفرنسيس في الجحيم(48).

وكان التصوير عند الأخ جوڤاني عملا دينياً كما كان متعة وانطلاقاً لحماسة الجمال. وكان مزاجه وهو يصور نفسه مزاجه وهو يصلي، ولم يبدأ قط تصويره دون أن يصلي قبل بدئه. وإذا كان قد تحرر من منافسات الحياة القاسية، فقد كان ينظر إلى هذه الحياة كأنها ترنيمة من الحب الإلهي والتوبة الإلهية. وكانت الصور التي يرسمها دينية على الدوام-حياة مريم والمسيح، والمنعمين في الجنة، وحياة القديسين ورؤساء طائفته. وكان غرضه هو أن يبث التقي أكثر مما يخلق الجمال، وجربا على هذه القاعدة رسم في البيت الذي يعقد فيه الرهبان اجتماعاتهم الصورة التي يظن أنها يجب أن تكون في ذهنهم على الدوام-صورة صلب المسيح، وهي تعبير قوي أظهر فيها أنجيلكو دراسته للأجسام العارية كما أظهر فيها في الوقت عينه الصفة العامة الشاملة للمسيحية. وقد صور فيها عند أسفل الصليب مع القديس دمنيك مؤسسي طوائف الرهبنة المنافسة لطائفته وهم - أوغسطين، وبندكت، وفرانسس، وجون جولبرتو John Gualberto مؤسس طائفة ڤالمبروزان Vallombosans، واكبرت مؤسس طائفة رهبان الكرمل. كذلك قص أنجيلكو، في الكوة التي فوق مدخل حجرة الاستقبال التي يطلب إلى الرهبان أن يقدموا فيها واجب الضيافة لكل عابر سبيل، قص في هذه الكوة قصة الحاج الذي تبين أنه هو المسيح نفسه، وكان يهدف بتصويره إلى أن كل حاج يجب أن يعامل على أنه قد يكون هو المسيح. وقد جمعت الآن في حجرة الاستقبال هذه بعض الموضوعات التي صورها أنجيلكو لمختلف الكنائس والحرف الطائفية: منها عذراء عمال الكتان وفيها جعل للملائكة المرنمين أجسام النساء اللدنة، ووجوه الأطفال الطاهرة الصريح، ولا تقل صورة النزول عن الصليب جمالا ورقة عن أية واحدة من ألف الصورة التي تمثل هذا المنظر في فن النهضة. أما صورة يوم الحساب فهي مسرفة بعض الإسراف في تناسب أجزائها، كما أنها مزدحمة بالخيالات المرعبة المنفرة كأنما العفو من صفات البشر والكره من صفات الله.

أما أروع صور أنجيلكو فتقوم في أعلى الدرج المؤدية إلى خلوات الرهبان، تلك هي صورة البشارة- وهي تصور ملكاً في منتهى الظرف والرشاقة يظهر الإجلال والتعظيم لمن ستكون أم المسيح، وتصور مريم تنحني، وتمسك كلتا يديها بالأخرى مظهرة بذلك خشوعها وعدم تصديقها. وقد وجد الراهب المحب من الوقت ما استطاع به أن يصور في الصوامع الخمسين بمساعدة تلاميذه الرهبان صوراً على الجص تذكر الرائي بمنظر ملهم من مظاهر الإنجيل كالتجلي، واجتماع الرسل حول العشاء الرباني، ومريم المجدلية تمسح قدمي المسيح. وصور أنجليكو في الصومعة المزدوجة التي ترهب فيها كوزيمو صورة لصلب المسيح، وأخرى لعبادة الملوك، تظهر فيها الثياب الشرقية الفخمة التي يحتمل أن الفنان قد شاهدها في مجلس مدينة فلورنس. ورسم في صومعته هو صورة تتويج العذراء، وكان موضوعها هو الموضوع المحبب له الذي صوره المرة بعد المرة، ويحتوي معرض أفيزي Uffizi على واحدة منقولة عنها، كما يحتوي مجمع فلورنس العلمي على واحدة أخرى، ومتحف اللوفر على ثالثة، وأحسنها كلها هي التي رسمها أنجيلكو لقاعة النوم في دير سان ماركو، لأن صورة المسيح ومريم في هذه الصورة من أبدع الصور في تاريخ الفن كله.

وذاعت شهرة هذه الصور الدالة على التقي والخشوع وتوالت بسببها على جوڤاني مئات الطلبات، وكان كلما جاء طلب منها رد على صاحبه بقوله إن عليه أولاً أن يحصل على موافقة رئيس الدير، فإذا حصل على هذه الموافقة أجابه إلى ما طلب على الدوام، ولما طلب إليه نقولاس الخامس أن يحضر إلى روما غادر صومعته في فلورنس وذهب ليزين معبد البابا بمناظر من حياة القديسين استيفن ولورنس، ولا تزال هذه الصور من أجمل ما تقع عليه العين في الفاتيكان، وبلغ من إعجاب نقولاس بالفنان أن عرض عليه منصب كبير أساقفة فلورنس، ولكن أنجيلكو اعتذر وأوصى بأن يعين في هذا المنصب رئيسه المحبوب، وقبل نقولاس هذا العرض، وبقى الراهب أنطونيو من القديسين حتى بعد أن لبس ثياب كبير الأساقفة.

وليس من بين المصورين جميعاً-إذا استثنينا إل گريكو El Greco (الإغريقي)- من ابتكر له طرازاً في التصوير خاصاً به كما ابتكر الأخ أنجيلكو، وفي وسع كل إنسان حتى المبتدئ أن يتبين هذا الطراز فلا يخطئ فيه. وهو يمتاز ببساطة الخط والشكل وهي البساطة التي ترجع إلى عهد جيتو، وقلة في مجموع الأوان ولكنها قلة أثيرية سماوية- تشمل الألوان الذهبي والزنجفري، والقرمزي، والأزرق، والأخضر-وهي تكشف عن روح نيرة، وإيمان هانئ، وصور رسمت في بساطة متناهية، تكاد تغفل علم التشريح، ووجوه جميلة، ظريفة، ولكنها شاحبة يبعدها عن الحياة، متشابهة تشابهاً يبعث الملل في الرهبان، والملائكة، والقديسين، كأنها في الفكرة التي قامت عليها أزهار في جنات النعيم، وكلها قد سمت بها روح بلغت المثل الأعلى في الحنان والخشوع، ونقاء المزاج والتفكير الذي يعيد إلى الذاكرة أجمل لحظات العصور الوسطى، ولا تستطيع النهضة أن ترجها. لقد كانت هذه آخر صرخة تبعثها العصور الوسطى في الفن. وظل الأخ جوڤاني يعمل سنة في روما، ثم عمل بعض الوقت في أورفيتو Orvreto، ثم كان مدة ثلاث سنين رئيساً لدير الدمنيك في فيسولي، ودعا مرة أخرى إلى رومة، حيث توفى في سن الثامنة والستين. وربما كان قلم لورندسوفلا الفصيح هو الذي كتب قبريته:

لست أريد أن يكون ما أمدح به أنني كنت أبليس آخر، بل أريد أن يكون سبب مديحي أنني خرجت عن جميع مكاسبي إلى المؤمنين بك أيها المسيح، لأن بعض الأعمال يتوجه بها إلى الأرض وبعضها إلى السماء. لقد كنت، أنا وجيوفني، من أبناء فلورنس المدينة التسكانية.

الڤاتيكان والعودة إلى توسكانيا، 1445–1455

In 1445 Pope Eugene IV summoned him to Rome to paint the frescoes of the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament at St Peter's, later demolished by Pope Paul III. Vasari suggests this might have been when Fra Angelico was offered the Archbishopric of Florence by Pope Nicholas V, to turn it down, recommending instead another friar. The story seems possible, and even likely. However, the detail does not tally. In 1445 the pope was Eugene IV. Nicholas was not to be elected until 6 March 1447. The archbishop in question during 1446–1459 was the Dominican Antoninus of Florence (Antonio Pierozzi), canonised by Pope Adrian VI in 1523. In 1447 Fra Angelico was in Orvieto with his pupil, Benozzo Gozzoli, executing works for the Cathedral. Among his other pupils were Zanobi Strozzi.[3]

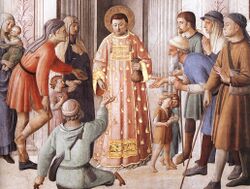

From 1447 to 1449 Fra Angelico was back at the Vatican, designing the frescoes for the Niccoline Chapel for Nicholas V. The scenes from the lives of the two martyred deacons of the Early Christian Church, St. Stephen and St. Lawrence may have been executed wholly or in part by assistants. The small chapel, with its brightly frescoed walls and gold leaf decorations gives the impression of a jewel box. From 1449 until 1452, Fra Angelico was back at his old convent of Fiesole, where he was the Prior.[2][4]

الوفاة والتطويب

In 1455, Fra Angelico died while staying at a Dominican convent in Rome, perhaps on an order to work on Pope Nicholas' chapel. He was buried in the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva.[2][4][5]

When singing my praise, don't liken my talents to those of Apelles.

Say, rather, that, in the name of Christ, I gave all I had to the poor.

The deeds that count on Earth are not the ones that count in Heaven.

I, Giovanni, am the flower of Tuscany.

— Translation of epitaph[2]

Apelles (see main article) was a highly renowned painter of Ancient Greece, whose output, now completely lost, is thought to have centred chronologically around 330 BCE.

On display near the main altar is a marble tombstone, an exceptional honour for an artist at that time. Two epitaphs were written, probably by Lorenzo Valla. The first reads: "In this place is enshrined the glory, the mirror, and the ornament of painters, John the Florentine. A religious and a true servant of God, he was a brother of the holy Order of Saint Dominic. His disciples mourn the death of such a great master, for who will find another brush like his? His homeland and his order mourn the death of a distinguished painter, who had no equal in his art." Inside a Renaissance style niche is the painter's relief in Dominican habit. A second epitaph reads: "Here lies the venerable painter Brother John of the Order of Preachers. May I be praised not because I looked like another Apelles, but because I have offered to you, O Christ, all my wealth. For some, their works survive on earth; for others in heaven. The city of Florence gave birth to me, John."

The English writer and critic William Michael Rossetti wrote of the friar:

From various accounts of Fra Angelico's life, it is possible to gain some sense of why he was deserving of canonization. He led the devout and ascetic life of a Dominican friar, and never rose above that rank; he followed the dictates of the order in caring for the poor; he was always good-humored. All of his many paintings were of divine subjects, and it seems that he never altered or retouched them, perhaps from a religious conviction that, because his paintings were divinely inspired, they should retain their original form. He was wont to say that he who illustrates the acts of Christ should be with Christ. It is averred that he never handled a brush without fervent prayer and he wept when he painted a Crucifixion. The Last Judgment and the Annunciation were two of the subjects he most frequently treated.[6][4]

Pope John Paul II beatified Fra Angelico on 3 October 1982, and in 1984 declared him patron of Catholic artists.[7]

Angelico was reported to say "He who does Christ's work must stay with Christ always". This motto earned him the epithet "Blessed Angelico", because of the perfect integrity of his life and the almost divine beauty of the images he painted, to a superlative extent those of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

التقييم

خلفية

Fra Angelico was working at a time when the style of painting was in a state of flux. This transformation had begun a century earlier with the works of Giotto and several of his contemporaries, notably Giusto de' Menabuoi. Both had created their major works in Padua, though Giotto had been trained in Florence by the great Gothic artist, Cimabue. He had painted a fresco cycle of St Francis in the Bardi Chapel in the Basilica di Santa Croce. Giotto had many enthusiastic followers, imitating his style in fresco. Some of them, notably the Lorenzetti, achieved great success.[8]

الرعاية

If not a monastic establishment, the patron was most usually, as part of a church's endowment, a family with wealth. To maximally advertise this (wealth) favoured subjects where religious devotion would be most focused, an altarpiece for instance. The wealthier the benefactor, the more the style would seem a throwback, compared with a freer and more nuanced style then in vogue. Underpinning this was that a commissioned painting said something about its sponsor: the more gold leaf, the more prestige accrued. Other precious materials in the paint-box were lapis lazuli and vermilion. Paints from these colours lent themselves poorly to a tonal treatment. The azure blue made of powdered lapis lazuli had to be applied flat. As with gold leaf, it was left to the depth and brilliance of colour to announce the patron's importance. This, however, constrained the overall style to that of an earlier generation. Thus, the impression left by altarpieces was more conservative than that achieved by frescoes. These, in contrast, were frequently of almost life-sized figures. To gain effect, they could capitalise on an up-to-date stage-set quality rather than having to fall back upon a lavish, but dated, display.[9]

معاصروه

Fra Angelico was the contemporary of Gentile da Fabriano. Gentile's altarpiece of the Adoration of the Magi, 1423, in the Uffizi is regarded as one of the greatest works of the style known as International Gothic. At the time it was painted, another young artist, known as Masaccio, was working on the frescoes for the Brancacci Chapel at the church of the Carmine. Masaccio had fully grasped the implications of the art of Giotto. Few painters in Florence saw his sturdy, lifelike and emotional figures and were not affected by them. His work partner was an older painter, Masolino, of the same generation as Fra Angelico. Masaccio died at 27, leaving the work unfinished.[8]

مذبح الكنيسة

The works of Fra Angelico reveal elements that are both conservatively Gothic and progressively Renaissance. In the altarpiece of the Coronation of the Virgin, painted for the Florentine church of Santa Maria Novella, are all the elements that a very expensive altarpiece of the 14th century was expected to provide; a precisely tooled gold ground, much azure, and much vermilion. The workmanship of the gilded haloes and gold-edged robes is exquisite and all very Gothic. What makes this a Renaissance painting, as against Gentile da Fabriano's masterpiece, is the solidity, three-dimensionality and naturalism of the figures and the realistic way in which their garments hang or drape around them. Even though it is clouds these figures stand upon, and not the earth, they do so with weight.[8]

الجصيات

The series of frescoes that Fra Angelico painted for the Dominican friars at San Marcos realise the advancements made by Masaccio and carry them further. Away from the constraints of wealthy clients and the limitations of panel painting, Fra Angelico was able to express his deep reverence for his God and his knowledge and love of humanity. The meditational frescoes in the cells of the convent have a quieting quality about them. They are humble works in simple colours. There is more mauvish pink than there is red, and the brilliant and expensive blue is almost totally lacking. In its place is dull green and the black and white of Dominican robes. There is nothing lavish, nothing to distract from the spiritual experiences of the humble people who are depicted within the frescoes. Each one has the effect of bringing an incident of the life of Christ into the presence of the viewer. They are like windows into a parallel world. These frescoes remain a powerful witness to the piety of the man who created them.[8] Vasari relates that Cosimo de' Medici seeing these works, inspired Fra Angelico to create a large Crucifixion scene with many saints for the Chapter House. As with the other frescoes, the wealthy patronage did not influence the Friar's artistic expression with displays of wealth.[2]

Masaccio ventured into perspective with his creation of a realistically painted niche at Santa Maria Novella. Subsequently, Fra Angelico demonstrated an understanding of linear perspective particularly in his Annunciation paintings set inside the sort of arcades that Michelozzo and Brunelleschi created at San' Marco's and the square in front of it.[8]

حيوات القديسين

When Fra Angelico and his assistants went to the Vatican to decorate the chapel of Pope Nicholas, the artist was again confronted with the need to please the very wealthiest of clients. In consequence, walking into the small chapel is like stepping into a jewel box. The walls are decked with the brilliance of colour and gold that one sees in the most lavish creations of the Gothic painter Simone Martini at the Lower Church of St Francis of Assisi, a hundred years earlier. Yet Fra Angelico has succeeded in creating designs which continue to reveal his own preoccupation with humanity, with humility and with piety. The figures, in their lavish gilded robes, have the sweetness and gentleness for which his works are famous. According to Vasari:

In their bearing and expression, the saints painted by Fra Angelico come nearer to the truth than the figures done by any other artist.[2]

It is probable that much of the actual painting was done by his assistants to his design. Both Benozzo Gozzoli and Gentile da Fabriano were highly accomplished painters. Benozzo took his art further towards the fully developed Renaissance style with his expressive and lifelike portraits in his masterpiece depicting the Journey of the Magi, painted in the Medici's private chapel at their palazzo.[11]

الذكرى الفنية

Through Fra Angelico's pupil Benozzo Gozzoli's careful portraiture and technical expertise in the art of fresco we see a link to Domenico Ghirlandaio, who in turn painted extensive schemes for the wealthy patrons of Florence, and through Ghirlandaio to his pupil Michelangelo and the High Renaissance.

Apart from the lineal connection, superficially there may seem little to link the humble priest with his sweetly pretty Madonnas and timeless Crucifixions to the dynamic expressions of Michelangelo's larger-than-life creations. But both these artists received their most important commissions from the wealthiest and most powerful of all patrons, the Vatican.

When Michelangelo took up the Sistine Chapel commission, he was working within a space that had already been extensively decorated by other artists. Around the walls the Life of Christ and Life of Moses were depicted by a range of artists including his teacher Ghirlandaio, Raphael's teacher Perugino and Botticelli. They were works of large scale and exactly the sort of lavish treatment to be expected in a Vatican commission, vying with each other in the complexity of design, number of figures, elaboration of detail and skilful use of gold leaf. Above these works stood a row of painted Popes in brilliant brocades and gold tiaras. None of these splendours have any place in the work which Michelangelo created. Michelangelo, when asked by Pope Julius II to ornament the robes of the Apostles in the usual way, responded that they were very poor men.[8]

Within the cells of San'Marco, Fra Angelico had demonstrated that painterly skill and the artist's personal interpretation were sufficient to create memorable works of art, without the expensive trappings of blue and gold. In the use of the unadorned fresco technique, the clear bright pastel colours, the careful arrangement of a few significant figures and the skillful use of expression, motion and gesture, Michelangelo showed himself to be the artistic descendant of Fra Angelico. Frederick Hartt describes Fra Angelico as "prophetic of the mysticism" of painters such as Rembrandt, El Greco and Zurbarán.[8]

انظر أيضاً

- قائمة الرسامين

- قائمة الرسامين الإيطاليين

- قائمة الإيطاليين المشاهير

- تصوير النهضة المبكر

- Poor Man's Bible

- Fray Angelico Chavez Franciscan Friar, historian and artist who was named after Fra Angelico due to his interest in painting.

- الرسم الغربي

- Frangelico – Italian liqueur named after Fra Angelico

الهامش

- ديورانت, ول; ديورانت, أرييل. قصة الحضارة. ترجمة بقيادة زكي نجيب محمود.

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists. Penguin Classics, 1965.

- ^ "Strozzi, Zanobi". The National Gallery, London. Archived from the original on 2007-10-14. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ أ ب ت Rossetti, William Michael (as attributed) (18 March 2016). "Fra Angelico". orderofpreachersindependent.org. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ The tomb has been given greater visibility since the beatification.

- ^ Rossetti 1911, p. 7.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةblessed - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHartt - ^ Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy,(1974) Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-881329-5

- ^ Zuffi, Stefano; Hyams, Jay; Seppi, Giorgio; Pauli, Tatjana; Scardoni, Sergio (2003). The Renaissance: 1401-1610: the splendor of European art. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 978-0-7607-4200-6. OCLC 53441832.

- ^ Paolo Morachiello, Fra Angelico: The San Marco Frescoes. Thames and Hudson, 1990. ISBN 0-500-23729-8

المراجع

- تحوي هذه المقالة معلومات مترجمة من الطبعة الحادية عشرة لدائرة المعارف البريطانية لسنة 1911 وهي الآن من ضمن الملكية العامةarticle "Angelico, Fra"كتبها William Michael Rossetti.

- Rossetti, William Michael. Angelico, Fra. 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Hood, William. Fra Angelico at San Marco. Yale University Press, 1993.

- Morachiello, Paolo. Fra Angelico: The San Marco Frescoes. Thames and Hudson, 1990. ISBN 0-500-23729-8

- Frederick Hartt, A History of Italian Renaissance Art, Thames & Hudson, 1970. ISBN 0-500-23136-2

- Giorgio Vasari. Lives of the Artists. first published 1568. Penguin Classics, 1965.

- Donald Attwater. The Penguin Dictionary of Saints. Penguin Reference Books, 1965.

- Luciano Berti. Florence, the city and its Art. Bercocci, 1979.

- Werner Cohn. Il Beato Angelico e Battista di Biagio Sanguigni. Revista d’Arte, V, (1955): 207–221.

- Stefano Orlandi. Beato Angelico; Monographia Storica della Vita e delle Opere con Un’Appendice di Nuovi Documenti Inediti. Florence: Leo S. Olschki Editore, 1964.

للاستزادة

- Didi-Huberman, Georges. Fra Angelico: Dissemblance and Figuration. University of Chicago Press, 1995. ISBN 0-226-14813-0 Discussion of how Fra Angelico challenged Renaissance naturalism and developed a technique to portray "unfigurable" theological ideas.

- Gilbert, Creighton, How Fra Angelico and Signorelli Saw the End of the World, Penn State Press, 2002 ISBN 0-271-02140-3

- Spike, John T. Angelico, New York, 1997.

- Supino, J. B., Fra Angelico, Alinari Brothers, Florence, undated, from Project Gutenberg

وصلات خارجية

- Fra Angelico – Painter of the Early Renaissance

- Fra Angelico in the "History of Art"

- Fra Angelico of Fiesole

- Fra Angelico Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, (October 26, 2005–January 29, 2006).

- "Soul Eyes" Review of the Fra Angelico show at the Met, by Arthur C. Danto in The Nation, (January 19, 2006).

- Fra Angelico, Catherine Mary Phillimore, (Sampson Low, Marston & Co., 1892)

- مقالات مأخوذة من الطبعة الحادية عشرة لدائرة المعارف البريطانية

- مواليد 1395

- وفيات 1455

- 15th-century Roman Catholic priests

- Italian Roman Catholic priests

- أشخاص من مقاطعة فلورنسا

- رسامو الكواتروتشنتو

- كاثوليك إيطاليون

- رسامون توسكانيون

- رسامو النهضة الإيطاليون

- Italian beatified people

- Roman Catholic Church painters

- Dominican beatified people

- Members of the Dominican Order

- 14th-century venerated Christians

- 15th-century venerated Christians

- Burials at Santa Maria sopra Minerva