زوهار

- للقرى في جنوب إسرائيل، انظر زوهار، إسرائيل و تسوخار. الاسم العلم "زوهار" هو اسم شائع بين الإسرائيليين.

| زوهار | |

|---|---|

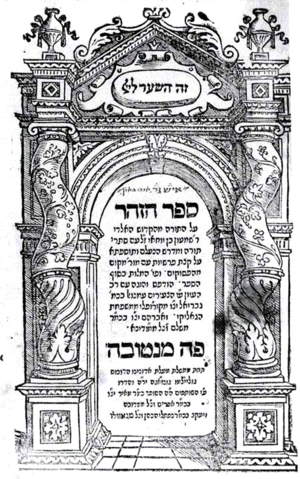

صفحة العنوان لأول نسخة مطبوعة من الزوهار، مانتوا، 1558، محفوظة في مكتبة الكونگرس | |

| معلومات | |

| الديانة | اليهودية |

| المؤلف | Moses de León |

| اللغة | الآرامية، Medieval Hebrew |

| الفترة | High medieval |

| النص الكامل | |

| جزء من سلسلة مقالات عن |

| القبالة |

|---|

|

زوهار (بالعبرية: זֹהַר, lit Splendor or Radiance؛ إنگليزية: Zohar) كلمة عبرية تعني «الإشراق » أو «الضياء». وكتاب الزوهار أهم كتب التراث القبَّالي، وهو تعليق صوفي مكتوب بالآرامية على المعنى الباطني للعهد القديم، ويعود تاريخه الافتراضي، حسب بعض الروايات، إلى ما قبل الإسلام والمسيحية، وهو ما يحقق الاستقلال الفكري (الوهمي) لليهود، وكتابته بلغة غريبة، تحقق العزلة لأعضاء الجماعات اليهودية الوظيفية. ويُنسَب الكتاب أيضاً إلى أحد معلمي المشناه (تنائيم) الحاخام شمعون بن يوحاي (القرن الثاني)، وإلى زملائه، ولكن يُقال إن موسى دي ليون (مكتشف الكتاب في القرن الثالث عشر) هو مؤلفه الحقيقي أو مؤلف أهم أجزائه، وأنه كتبه بين عامي 1280 و1285، مع بدايات أزمة يهود إسبانيا. والزوهار، في أسلوبه، يشبه المواعظ اليهودية الإسبانية في ذلك الوقت. وبعد مرور مائة عام على ظهوره، أصبح الزوهار بالنسبة إلى المتصوفة في منزلة التلمود بالنسبة إلى الحاخاميين. وقد شاع الزوهار بعد ذلك بين اليهود، حتى احتل مكانة أعلى من مكانة التلمود، وخصوصاً بعد ظهور الحركة الحسيدية.

ويتضمن الزوهار ثلاثة أقسام هي: الزوهار الأساسي، وكتاب الزوهار نفسه، ثم كتاب الزوهار الجديد. ومعظم الزوهار يأخذ شكل تعليق أو شرح على نصوص من الكتاب المقدَّس، وخصوصاً أسفار موسى الخمسة، ونشيد الأنشاد، وراعوث، والمراثي. وهو عدة كتب غير مترابطة تفتقر إلى التناسق وإلى تحديد العقائد. ويضم الزوهار مجموعة من الأفكار المتناقضة والمتوازية عن الإله وقوى الشر والكون. وفيه صور مجازية ومواقف جنسية صارخة تجعله شبيهاً بالكتب الإباحية وهو ما ساهم في انتشاره وشعبيته. والمنهج الذي يستخدمه ليس مجازياً تماماً، ولكنه ليس حرفياً أيضاً، فهو يفترض أن ثمة معنى خصباً لابد من كشفه، ويفرض المفسر المعنى الذي يريده على النص من خلال قراءة غنوصية تعتمد على رموز الحروف العبرية، ومقابلها العددي. وتُستخدَم أربعة طرق للشرح والتعليق تُسمَّى «بارديس»، بمعنى «فردوس» وصولاً إلى المعنى الخفي، وهي:

1 ـ بيشات: التفسير الحرفي.

2 ـ ريميز: التأويل الرمزي.

3 ـ ديروش: الدرس الشرحي المكثَّف.

4 ـ السود: السر الصوفي.

والزوهار مكتوب بأسلوب آرامي مُصطَنع، يمزج أسلوب التلمود البابلي بترجوم أونكلوس، ولكن وراء الغلالة الآرامية المصطنعة يمكن اكتشاف عبرية العصور الوسطى. وهو كتاب طويل جداً، يتألف من ثمانمائة وخمسين ألف كلمة في لغته الأصلية.

والموضوعات الأساسية التي يعالجها الزوهار هي: طبيعة الإله وكيف يكشف عن نفسه لمخلوقاته، وأسرار الأسماء الإلهية، وروح الإنسان وطبيعتها ومصيرها، والخير والشر، وأهمية التوراة، والماشيَّح والخلاص. ولما كانت كل هذه الموضوعات مترابطة بل متداخلة تماماً في نطاق الإطار الحلولي، فإن كتاب الزوهار حين يتحدث عن الإله، فإنه يتحدث في الوقت نفسه عن التاريخ والطبيعة والإنسان، وإن كان جوهر فكر الزوهار هو تَوقُّع عودة الماشيَّح، الأمر الذي يخلع قدراً كبيراً من النسبية على ما يحيط بأعضاء الجماعات اليهودية من حقائق تاريخية واجتماعية.

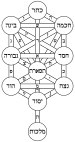

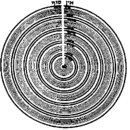

ويتحدث الزوهار عن التجليات النورانية العشرة (سفيروت) التي يجتازها الإله للكشف عن نفسه. كما يشير الكتاب إلى هذه التجليات باعتبارها أوعية أو تيجاناً أو كلمات تشكل البنية الداخلية للألوهية. وتُعَدُّ هذه الصورة (رؤية الإله لا باعتباره وحدة متكاملة وإنما على هيئة أجزاء متحدة داخل بناء واحد) من أكثر أفكار الزوهار جسارة، كما كان لها أعمق الأثر في التراث القبَّالي.

التأليف

وجهة النظر الأولى

وقد ظهرت أولى طبعات الزوهار خلال الفترة من 1558 إلى 1560 في مانتوا وكريمونا في إيطاليا. وظهرت طبعة كاملة له في القدس (1945-1958) تقع في اثنين وعشرين مجلداً، وتحتوي على النص الآرامي يقابله النص العبري. وقد ظهرت ترجمات لاتينية لبعض أجزاء كتاب الزوهار (ابتداءً من القرن السابع عشر). كما تُرجم إلى الفرنسية في ستة أجزاء (1906-1911)، وإلى الإنجليزية في خمسة أجزاء (1931-1934). ومن أشهر طبعاته طبعة ڤلنا التي يبلغ عدد صحفاتها ألفاً وسبعمائة صفحة.

وجهة النظر الدينية المعاصرة

المحتوى

Printings, editions, and indexing

Tikunei haZohar was first printed in Mantua in 1557. The main body of the Zohar was printed in Cremona in 1558 (a one-volume edition), in Mantua in 1558-1560 (a three-volume edition), and in Salonika in 1597 (a two-volume edition). Each of these editions included somewhat different texts.[1] When they were printed there were many partial manuscripts in circulation that were not available to the first printers. These were later printed as Zohar Chadash (lit. "New Radiance"), but Zohar Chadash actually contains parts that pertain to the Zohar, as well as Tikunim (plural of Tikun, "Repair", see also Tikkun olam) that are akin to Tikunei haZohar, as described below. The term Zohar, in usage, may refer to just the first Zohar collection, with or without the applicable sections of Zohar Chadash, or to the entire Zohar and Tikunim.

Citations referring to the Zohar conventionally follow the volume and page numbers of the Mantua edition, while citations referring to Tikkunei haZohar follow the edition of Ortakoy (Constantinople) 1719 whose text and pagination became the basis for most subsequent editions. Volumes II and III begin their numbering anew, so citation can be made by parashah and page number (e.g. Zohar: Nasso 127a), or by volume and page number (e.g. Zohar III:127a).[citation needed]

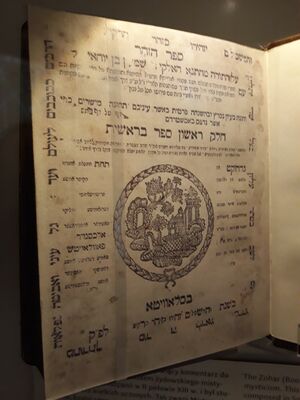

The New Zohar (זוהר חדש)

After the book of the Zohar had been printed (in Mantua and in Cremona, in the Jewish years 5318–5320 or 1558–1560? CE), many more manuscripts were found that included paragraphs pertaining to the Zohar which had not been included in printed editions. The manuscripts pertained also to all parts of the Zohar; some were similar to Zohar on the Torah, some were similar to the inner parts of the Zohar (Midrash haNe'elam, Sitrei Otiyot and more), and some pertained to Tikunei haZohar. Some thirty years after the first edition of the Zohar was printed, the manuscripts were gathered and arranged according to the parashiyot of the Torah and the megillot (apparently the arrangement was done by the Kabbalist, Avraham haLevi of Tsfat), and were printed first in Salonika in Jewish year 5357 (1587? CE), and then in Kraków (5363), and afterwards in various editions.[2]

Structure

According to Scholem, the Zohar can be divided into 21 types of content, of which the first 18 (a.–s.) are the work of the original author (probably de Leon) and the final 3 (t.–v.) are the work of a later imitator.

a. Untitled Torah commentary

A "bulky part" which is "wholly composed of discursive commentaries on various passages from the Torah".[3]

b. Book of Concealment (ספרא דצניעותא)

A short part of only six pages, containing a commentary to the first six chapters of Genesis. It is "highly oracular and obscure," citing no authorities and explaining nothing.

c. Greater Assembly (אדרא רבא)

This part contains an explanation of the oracular hints in the previous section. Ben Yochai's friends gather together to discuss secrets of Kabbalah. After the opening of the discussion by ben Yochai, the sages rise, one after the other, and lecture on the secret of Divinity, while ben Yochai adds to and responds to their words. The sages become steadily more ecstatic until three of them die. Scholem calls this part "architecturally perfect."

d. Lesser Assembly (אדרא זוטא)

Ben Yochai dies and a speech is quoted in which he explains the previous section.

e. Assembly of the Tabernacle (אדרא דמשכנא)

This part has the same structure as c. but discusses instead the mysticism of prayer.

f. Palaces (היכלות)

Seven palaces of light are described, which are perceived by the devout in death. This description appears again in another passage, heavily embellished.

g. Secretum Secretorum (רזא דרזין)

An anonymous discourse on physiognomy and a discourse on chiromancy by ben Yochai.

h. Old Man (סבא)

An elaborate narrative about a speech by an old Kabbalist.

i. Child (ינוקא)

A story of a prodigy and his Kabbalistic speech.

k. Head of the Academy (רב מתיבתא)

A Pardes narrative in which a head of the celestial academy reveals secrets about the destinies of the soul.

l. Secrets of Torah (סתרי תורה)

Allegorical and mystical interpretations of Torah passages.

m. Mishnas (מתניתין)

Imitations of the Mishnaic style, designed to introduce longer commentaries in the style of the Talmud.

n. Zohar to the Song of Songs

Kabbalistic commentary to the Song of Songs.

o. Standard of Measure (קו המידה)

Profound interpretation of Deut. 6:4.

p. Secrets of Letters (סתרי אותיות)

A monologue by ben Yochai on the letters in the names of God and their use in creation.

q. Commentary to the Merkabah

r. Mystical Midrash (מדרש הנעלם)

A Kabbalistic commentary on the Torah, citing a wide variety of Talmudic sages. According to Ramaz, it is fit to be called Midrash haNe'elam because "its topic is mostly the neshamah (an upper level of soul), the source of which is in Beri'ah, which is the place of the upper Gan Eden; and it is written in the Pardes that drash is in Beri'ah... and the revealed midrash is the secret of externality, and Midrash haNe'elam is the secret of internality, which is the neshamah. And this derush is founded on the neshamah; its name befits it—Midrash haNe'elam.[4]

The language of Midrash haNe'elam is sometimes Hebrew, sometimes Aramaic, and sometimes both mixed. Unlike the body of the Zohar, its drashot are short and not long. Also, the topics it discusses—the work of Creation, the nature of the soul, the days of Mashiach, and Olam Haba—are not of the type found in the Zohar, which are the nature of God, the emanation of worlds, the "forces" of evil, and more.

s. Mystic Midrash on Ruth

A commentary on the Book of Ruth in the same style.

t. Faithful Shepherd (רעיא מהימנא)

By far the largest "book" included in the Zohar, this is a Kabbalistic commentary on Moses' teachings revealed to ben Yochai and his friends.[2] Moshe Cordovero said, "Know that this book, which is called Ra'aya Meheimna, which ben Yochai made with the tzadikim who are in Gan Eden, was a repair of the Shekhinah, and an aid and support for it in the exile, for there is no aid or support for the Shekhinah besides the secrets of the Torah... And everything that he says here of the secrets and the concepts—it is all with the intention of unifying the Shekhinah and aiding it during the exile.[5]

u. Rectifications of the Zohar (תקוני זוהר)

Tikunei haZohar, which was printed as a separate book, includes seventy commentaries called Tikunim (lit. Repairs) and an additional eleven Tikunim. In some editions, Tikunim are printed that were already printed in the Zohar Chadash, which in their content and style also pertain to Tikunei haZohar.[2]

Each of the seventy Tikunim of Tikunei haZohar begins by explaining the word Bereishit (בראשית), and continues by explaining other verses, mainly in parashat Bereishit, and also from the rest of Tanakh. And all this is in the way of Sod, in commentaries that reveal the hidden and mystical aspects of the Torah.

Tikunei haZohar and Ra'aya Meheimna are similar in style, language, and concepts, and are different from the rest of the Zohar. For example, the idea of the Four Worlds is found in Tikunei haZohar and Ra'aya Meheimna but not elsewhere, as is true of the very use of the term "Kabbalah". In terminology, what is called Kabbalah in Tikunei haZohar and Ra'aya Meheimna is simply called razin (clues or hints) in the rest of the Zohar.[6] In Tikunei haZohar there are many references to chibura kadma'ah (meaning "the earlier book"). This refers to the main body of the Zohar.[6]

v. Further Additions

These include later Tikkunim and other texts in the same style.

التأثير

اليهودية

On the one hand, the Zohar was lauded by many rabbis because it opposed religious formalism, stimulated one's imagination and emotions, and for many people helped reinvigorate the experience of prayer.[7] In many places prayer had become a mere external religious exercise, while prayer was supposed to be a means of transcending earthly affairs and placing oneself in union with God.[7]

According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, "On the other hand, the Zohar was censured by many rabbis because it propagated many superstitious beliefs, and produced a host of mystical dreamers, whose overexcited imaginations peopled the world with spirits, demons, and all kinds of good and bad influences."[7] Many classical rabbis, especially Maimonides, viewed all such beliefs as a violation of Jewish principles of faith. Its mystic mode of explaining some commandments was applied by its commentators to all religious observances, and produced a strong tendency to substitute mystic Judaism in the place of traditional Rabbinic Judaism.[7] For example, Shabbat, the Jewish Sabbath, began to be looked upon as the embodiment of God in temporal life, and every ceremony performed on that day was considered to have an influence upon the superior world.[7]

Elements of the Zohar crept into the liturgy of the 16th and 17th centuries, and the religious poets not only used the allegorism and symbolism of the Zohar in their compositions, but even adopted its style, e.g. the use of erotic terminology to illustrate the relations between man and God.[7] Thus, in the language of some Jewish poets, the beloved one's curls indicate the mysteries of the Deity; sensuous pleasures, and especially intoxication, typify the highest degree of divine love as ecstatic contemplation; while the wine-room represents merely the state through which the human qualities merge or are exalted into those of God.[7]

The Zohar is also credited with popularizing de Leon's PaRDeS codification of biblical exegesis.[citation needed]

الصوفية المسيحية

According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, "The enthusiasm felt for the Zohar was shared by many Christian scholars, such as Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, Johann Reuchlin, Aegidius of Viterbo, etc., all of whom believed that the book contained proofs of the truth of Christianity.[8] They were led to this belief by the analogies existing between some of the teachings of the Zohar and certain Christian dogmas, such as the fall and redemption of man, and the dogma of the Trinity, which seems to be expressed in the Zohar in the following terms:

The Ancient of Days has three heads. He reveals himself in three archetypes, all three forming but one. He is thus symbolized by the number Three. They are revealed in one another. [These are:] first, secret, hidden 'Wisdom'; above that the Holy Ancient One; and above Him the Unknowable One. None knows what He contains; He is above all conception. He is therefore called for man 'Non-Existing' [Ayin][8] (Zohar, iii. 288b).

According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, "This and other similar doctrines found in the Zohar are now known to be much older than Christianity, but the Christian scholars who were led by the similarity of these teachings to certain Christian dogmas deemed it their duty to propagate the Zohar."[8]

تعليقات

- The first known commentary on the book of Zohar, Ketem Paz, was written by Simeon Lavi of Libya.

- Another important and influential commentary on Zohar, 22-volume Or Yakar, was written by Moshe Cordovero of the Tzfat (i.e. Safed) kabbalistic school in the 16th century.

- The Vilna Gaon authored a commentary on the Zohar.

- Tzvi Hirsch of Zidichov wrote a commentary on the Zohar entitled Ateres Tzvi.

- A major commentary on the Zohar is the Sulam written by Yehuda Ashlag.

- A full translation of the Zohar into Hebrew was made by the late Daniel Frish of Jerusalem under the title Masok MiDvash.

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

المصادر

- ^ Doktór, Jan; Bendowska, Magda (2012). "Sefer haZohar – the Battle for Editio Princeps". Jewish History Quarterly. 2 (242): 141–161. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت Much of the information on contents and sections of the Zohar is found in the book Ohr haZohar(אור הזוהר) by Rabbi Yehuda Shalom Gross, in Hebrew, published by Mifal Zohar Hoilumi, Ramat Beth Shemesh, Israel, Heb. year 5761 (2001 CE); also available at http://israel613.com/HA-ZOHAR/OR_HAZOHAR_2.htm Archived 2012-04-10 at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 1, 2012; explicit permission is given in both the printed and electronic book "to whoever desires to print paragraphs from this book, or the entire book, in any language, in any country, in order to increase Torah and fear of Heaven in the world and to awaken hearts our brothers the children of Yisrael in complete teshuvah".

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:0 - ^ the Ramaz, brought in Mikdash Melekh laZohar, parashat Vayeira, Zalkova edition, p. 100

- ^ Ohr haChamah laZohar, part 2, p. 115b, in the name of the Ramak

- ^ أ ب According to Rabbi Yaakov Siegel, in an email dated February 29, 2012, to ~~Nissimnanach

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةjewcyclo - ^ أ ب ت Jacobs, Joseph; Broydé, Isaac. "Zohar". Jewish Encyclopedia. Funk & Wagnalls Company.

وصلات خارجية

Zohar texts

ספר הזהר, Sefer haZohar, Zohar text in original Aramaic

ספר הזהר, Sefer haZohar, Zohar text in original Aramaic Translation:Zohar at English Wikisource

Translation:Zohar at English Wikisource- Zohar Pages in English, at ha-zohar.net, including the Introduction translated in English, and The Importance of Study of the Zohar, and more

- Complete Zohar, Tikkunim, and Zohar Chadash in Aramaic with Hebrew translation, in 10 volumes of PDF, divided for yearly or 3-year learning

- A four-pages-per-sheet PDF arrangement of the above, allowing for printing on 3 reams of Letter paper duplex Archived 2021-01-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Zohar and Related Booklets in various formats in PDF files, at ha-zohar.net

- Sefer haZohar, Mantua edition (1558), at the National Library of Israel, DjVu file

- Sefer haZohar, Cremona edition (1559), at the National Library of Israel, DjVu file

- Zohar text files (TXT HTML) among grimoar.cz Hebrew Kabbalistic texts collection

- The Zohar in English: Bereshith to Lekh Lekha

- The Zohar in English: some mystical sections

- The Kabbalah Center translation of the Zohar

- Original Zohar with Sulam Commentary

- Daily Zohar study of Tikunei Zohar in English

- Tikkunei Zohar in English, Partial (Intro and Tikkun 1-17) at ha-zohar.info; permanent link

- Copy of the Zohar

Links about the Zohar

- The Aramaic Language of the Zohar

- 7 brief video lectures about The Zohar from Kabbalah Education & Research Institute

- Zohar and Later Mysticism, a short essay by Israel Abrahams

- Notes on the Zohar in English: An Extensive Bibliography

- The Zohar Code: The Temple Calendar of King Solomon[dead link]

- The Zohar on the website of the National Library of Israel

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing عبرية-language text

- Articles that link to foreign-language Wikisources

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2015

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2024

- Portal templates with default image

- Articles with dead external links from February 2023

- 1280s books

- Apocalyptic literature

- Hebrew-language names

- Jewish texts in Aramaic

- Kabbalah texts

- Visionary literature

- نصوص القبالة