المتشككة

| جزء من سلسلة مقالات عن |

| الپيرّونية |

|---|

|

|

|

الپيرّونية Pyrrhonism، أو الشك الپيرّوني Pyrrhonian skepticism، كانت مدرسة في مذهب الشك أسسها أنسيدموس Aenesidemus في القرن الأول ق.م. ودوَّنها سكستوس إمپريكوس في أواخر القرن الثاني أو أوائل القرن الثالث الميلادي. وقد أخذت اسمها من پيرّون Pyrrho، الفيلسوف الذي عاش من ح. 360 إلى ح. 270 ق.م.، بالرغم من أن العلاقة بين فلسفة المدرسة والشخصية التاريخية يكتنفها عدم الوضوح. وقد حدثت نهضة للمصطلح في القرن 17 عند مولد النظرة العلمية للعالَم.

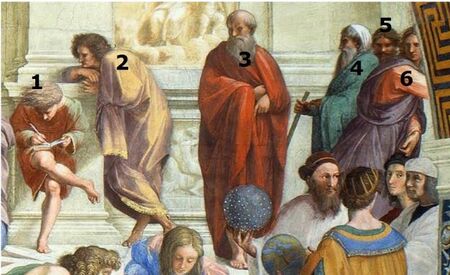

لقد احتفظت أثينة في هذه الثقافة الهلنستية- وكانت هي أم الكثير، وسيدة الجزء الأكبر، منها- احتفظت فيها بمكان الزعامة في ميدانين: التمثيل والفلسفة. ولم يكن العالم منهمكاً في الحروب والثورات، والعلوم الجديدة والأديان الجديدة، وحب المال والجري وراء المال، لم يكن منهمكاً في هذا كله إلى حد لا يستطيع معه أن يجد بعض الوقت ينفقه في المشاكل التي لا يجد لها جواباً، ولكنها لا تنفك تواجَه فلا يستطيع منه فراراً، مسائل الخطأ والصواب، والمادة، والعقل، والحرية والضرورة، والنبل والخسة، والحياة والموت. وقدم الشبان من جميع مدن البحر الأبيض المتوسط، وكثير ما كانوا يلاقون أشد الصعاب وهم قادمون، ليدرسوا في الأبهاء والحدائق التي خلفها أفلاطون وأرسطو آثاراً لهما خالدة من بعدهما.

وواصل ثاوفراسطوس اللسبوسي المجد النشط في اللوقيين تقاليد الطريقة الأختبارية. لقد كان المشاءون علماء وباحثين أكثر منهم فلاسفة، وهبوا حياتهم للبحث المتخصص في علوم الحيوان والنبات، والسير، وتاريخ العلوم، والفلسفة، والأدب، والقانون. وارتاد ثاوفراسطوس في أثناء زعامته العلمية التي دامت أربعاً وثلاثين سنة (322- 288) ميادين علمية كثيرة، ونشر بحوثه في أربعمائة مجلد تكاد تعالج كل موضوع من الحب إلى الحرب. وقد شدد النكير على النساء في رسالته "في الزواج"، فردت علمية لينتيوم محظية أبيقور برسالة غزيرة المادة، شديدة الوقع عليهِ، فندت فيها أراءه(1). ومع هذا فإن ثنيوس يعزو إلى ثاوفراسطوس ذلك القول الدال على رقعة العاطفة:

"إن التواضع هو الذي يجعل الجمال جميلاً(2)"

ويصفه ديوجين ليرتس بأنه "من أحب الناس للخير ومن أكثرهم ظرفاً". وقد بلغ من فصاحته أن نسي الناس اسمه الأول فلم يذكروه إلا بالاسم الذي أطلقه عليه أرسطو والذي يعني أنه يتكلم كما تتكلم الآلهة؛ وقد بلغ من حب الناس إياه أن ألفين من الطلاب كانوا يهرعون إلى سماع محاضراته، وكان مناندر من أخلص أتباعه(3). وقد عني الناس من بعده أشد العناية بالاحتفاظ بكتابه في "الأخلاق"، ولم يكن احتفاظهم به لأنه أوجد طرازاً جديداً في الأدب، بل لأنه سخر أشد السخرية من الأخطاء التي يعزوها الناس جميعاً لغيرهم من الناس. فهنا الرجل الثرثار الذي يبدأ بمدح زوجته، ثم يروي الرؤيا التي نراها في الليلة السابقة، ويعدد أصناف الأطعمة التي تناولها في العشاء صنفاً صنفاً؛ ثم يختم حديثه بقولهِ "إننا لم نعد كما كنا" من قبل الأيام الخالية. وهنا الرجل الغبي الذي "إذا ذهب ليشاهد مسرحية، تركه الناس في آخر التمثيل مستغرقاً في النوم في الدار الخاوية... فهو يثقل معدته بالعشاء الدسم، فيضطر إلى السهر ليلاً، ويعود إلى منزله وهو بين النوم واليقظة، فلا يعرف بابه، ويعضه كلب جاره(4)".

ومن الحوادث القليلة في حياة ثاوفراسطوس أن الدولة أصدرت مرسوماً (307) يحتم موافقة الجمعية على من يُختارون لرياسة المدارس الفلسفية. وحوالي هذا الوقت نفسه، وجه أگنونيدز Agnonides إلى ثاوفراسطوس التهمة القديمة، تهمة المروق من الدين؛ فما كان من ثاوفراسطوس إلا أن غادر أثينة في هدوء، ولكن الطلاب الذين غادروها بعده بلغوا من الكثرة حداً جعل التجار يجأرون بالشكوى من كساد بضاعتهم الذي يوشك أن يحل بهم الخراب. فلم تمضِ سنة على صدور المرسوم حتى اضطرت الدولة إلى إلغائه، وعاد ثاوفراسطوس ظافراً ليرأس اللوقيين ويظل رئيساً لها إلى قرب وفاته في سن الخامسة والثمانين. ويقال إن "أثينة بأجمعها" شيعت جنازته. ولم تبقَ مدرسة المشائين طويلاً بعد وفاته؛ ذلك أن العلم خرج من أثينة بعد أن افتقرت إلى الإسكندرية الغنية الرخية، وانحطت اللوقيون التي كانت قد وهبت نفسها للبحث العلمي فلم يعد يسمع الناس عنها إلا القليل.

وفي هذه الأثناء كان اسپيوسپوس Speusippus قد خلف أفلاطون أكسانوقراطيس اسبيوسبوس Xenocrates Speusippus في المجمع العلمي. وظل أكسانوقراطيس يحكم المجمع ربع قرن من الزمان (339- 314)، ورفع من شأن الفلسفة بحياته النبيلة البسيطة. وقد انهمك في الدرس والتعليم، فلم يكن يترك المجمع إلا مرة واحدة في العام ليشهد المآسي الديونيشية، ويقول ليرتيوس إنه كان إذا ظهر "أفسح الطريق له غوغاء المدينة المشاكسون المشاغبون(5)". وكان يأبى أن يتقاضى أجراً ما على عملهِ. وبلغ من فقره أن كاد يُزج به في السجن لعجزه عن أداء الضرائب، ولكن أمتريوس الفالرومي أدى عنه ما كان متأخراً عليه وأطلق سراحه. وقال فليب المقدوني إن أكسانوقراطيس كان أطهر يداً من جميع الشعراء الأثينيين الذين أرسلوا إليه. وقد تضايقت فريني Phryne من اشتهاره بالفضيلة، فادعت أن بعض الناس يطاردونها، ولجأت إلى بيته، ولما رأت أن ليس فيهِ إلا سرير واحد سألته هل يقبل أن تنام معه فيه. وأجابها إلى ما طلبت مدفوعاً إلى ذلك، على ما يقال لنا، بعوامل إنسانية محضة؛ ولكنه بلغ من بروده وعدم استجابته لتوسلاتها وفتنتها، أن فرت من فراشهِ وضيافتهِ، وشكته إلى أصدقائهِ قائلة إنها وجدت تمثالاً لا رجلاً(6). ذلك أن أكسانوقراطيس لم يكن يريد أن يعشق غير الفلسفة.

ولما مات أوشكت النزعة الميتافيزيقية في التفكير اليوناني أن يُقضى عليها في الأيكة التي كانت مزارها ومتعبدها. ذلك أن خلفاء أفلاطون كانوا من علماء الرياضة والأخلاق، وقلما كانوا ينفقون شيئاً من وقتهم في دراسة المسائل المجردة التي كانت من قبل تتردد بين جوانب المجمع العلمي، واستعادت تحديات زينون الإليائي التشككية، ونزعة هرقيطس الموضوعية، وتشكك گورگياس پروتاگوراس المنظم، ولا أدرية سقراط، وأرستپوس وإقليدس المجاري، استعادت هذه كلها ما كان لها من سيطرة على الفلسفة اليونانية، وكان ذلك خاتمة عصر العقل. لقد فكروا في كل فرض من الفروض العلمية، وبحث ثم نسي وأهمل؛ واحتفظ الكون بأسرارهِ، ومل الناس البحث الذي عجزت عنه أنبه العقول نفسها. وكان أرسطو قد اتفق مع أفلاطون في نقطة واحدة- وهي أن في الإمكان الوصول إلى الحقيقة النهائية(7). وعبر بيرون Pyrrho وهي تشكك عصره بقولهِ إن هذه النقطة هي التي أخطأ فيها الفيلسوفان أكثر مما أخطأا في أية نقطة أخرى.

وولد پيرون في إليس Elis حوالي عام 360 وسار مع جيش الإسكندر الزاحف على الهند، وتلقى العلم على "من فيها من" السوفسطائيين العراة Gmnosophists، ولعله أخذ عنهم بعض آرائهم عن التشكك الذي صار اسمه مرادفاً له في ما بعد. ولما عاد إلى إليس عاش فقيراً يعلم الناس الفلسفة. وقد منعه الحياء من تأليف الكتب، ولكن تلميذه تيمون الفليوسي Timon of Phlius نشر آراء بيرون في أنحاء العالم في سلسلة من رسائل الهجاء (Silloli). وكانت هذه الآراء تقوم على قواعد رئيسية أولها: أن الحقيقة لا يمكن الوصول إليها، وأن الرجل العاقل يرجئ حكمه، ويبحث عن الطمأنينة لا عن الحقيقة؛ وأنه لما كانت كل النظريات خاطئة في أغلب الظن فإن من الخير للإنسان أن يقبل أساطير زمانه ومكانه وما جرى به العرف فيهما. وثانيتهما أن ليس في مقدور الحواس والعقل أن تمدنا بعلم أكيد: فالحواس تشوه الشيء الخارجي حين تحسه، وليس العقل إلا خادم الشهوات المخالط المخادع. وكل قياس منطقي يصادر على المحمول لأن قضيته الكبرى تفترض صحة النتيجة. "وكل علة لها علة تقابلها وتناقضها(8)"؛ والتجربة الواحدة قد تكون سارة حسب الظروف المحيطة بها ومزاج صاحبها؛ والشيء الواحد قد يبدو صغيراً أو كبيراً، قبيحاً أو جميلاً؛ والعمل الواحد قد يُعد فضيلة أو رذيلة حسب المكان والزمان الذين نعيش فيهما؛ والآلهة نفسها قد تكون وقد لا تكون حسب اعتقاد أمم الخلائق المختلفة؛ وكل شيء هو رأي، ولا شيء قط حقيقي كل الحق- فمن الحمق إذن أن ينحاز الإنسان في المنازعات إلى هذا الجانب أو ذاك، أو أن يبحث له عن مكان آخر يعيش فيهِ أو طريقة أخرى يعيش بها، أو أن يحسد المستقبل أو الماضي؛ فالرغبات كلها خداع باطل. وحتى الحياة نفسها خير غير مؤكد، والموت نفسه ليس شراً مؤكداً، والواجب على الإنسان أن لا يتحيز ضد هذا الشيء وذاك. وثالثة هذه القواعد أن أفضل الأشياء جميعاً للإنسان أن يقبل الحياة كما هي في هدوء واطمئنان، فلا يحاول إصلاح العالم، بل يرضى به وهو صابر عليه، ولا ينهمك في العمل على تقدمه، بل يقنع بالسلام. وحاول بيرون مخلصاً أن يسير في حياته على هدى هذه الفلسفة النصف الهندية، فخضع لعادات إليس وعبادتها، ولم يبذل جهداً ما في تجنب الأخطار أو إطالة حياته(9)، ومات في سن التسعين. وأحبه مواطنوه ورضوا عنه وكرموه بأن أعفوا زملائه الفلاسفة من الضرائب.

الفلسفة

The goal of Pyrrhonism is ataraxia,[1] an untroubled and tranquil condition of soul that results from a suspension of judgement, a mental rest owing to which we neither deny nor affirm anything.

Pyrrhonists dispute that the dogmatists – which includes all of Pyrrhonism's rival philosophies – claim to have found truth regarding non-evident matters, and that these opinions about non-evident matters (i.e., dogma) are what prevent one from attaining eudaimonia. For any of these dogmas, a Pyrrhonist makes arguments for and against such that the matter cannot be concluded, thus suspending judgement, and thereby inducing ataraxia.

Pyrrhonists can be subdivided into those who are ephectic (engaged in suspension of judgment), aporetic (engaged in refutation)[2] or zetetic (engaged in seeking).[3] An ephectic merely suspends judgment on a matter, "balancing perceptions and thoughts against one another."[4] It is a less aggressive form of skepticism, in that sometimes "suspension of judgment evidently just happens to the sceptic".[5] An aporetic skeptic, in contrast, works more actively towards their goal, engaging in the refutation of arguments in favor of various possible beliefs in order to reach aporia, an impasse, or state of perplexity,[6] which leads to suspension of judgement.[5] Finally, the zetetic claims to be continually searching for the truth but to have thus far been unable to find it, and thus continues to suspend belief while also searching for reason to cease the suspension of belief.

الأنماط

Although Pyrrhonism's objective is ataraxia, it is best known for its epistemological arguments. The core practice is through setting argument against argument. To aid in this, the Pyrrhonist philosophers Aenesidemus and Agrippa developed sets of stock arguments known as "modes" or "tropes."

The ten modes of Aenesidemus

Aenesidemus is considered the creator of the ten tropes of Aenesidemus (also known as the ten modes of Aenesidemus)—although whether he invented the tropes or just systematized them from prior Pyrrhonist works is unknown. The tropes represent reasons for suspension of judgment. These are as follows:[7]

- Different animals manifest different modes of perception;

- Similar differences are seen among individual men;

- For the same man, information perceived with the senses is self-contradictory

- Furthermore, it varies from time to time with physical changes

- In addition, this data differs according to local relations

- Objects are known only indirectly through the medium of air, moisture, etc.

- These objects are in a condition of perpetual change in colour, temperature, size and motion

- All perceptions are relative and interact one upon another

- Our impressions become less critical through repetition and custom

- All men are brought up with different beliefs, under different laws and social conditions

According to Sextus, superordinate to these ten modes stand three other modes: that based on the subject who judges (modes 1, 2, 3 & 4), that based on the object judged (modes 7 & 10), that based on both subject who judges and object judged (modes 5, 6, 8 & 9), and superordinate to these three modes is the mode of relation.[8]

الأنماط الخمسة لأگريپا

These "tropes" or "modes" are given by Sextus Empiricus in his Outlines of Pyrrhonism. According to Sextus, they are attributed only "to the more recent skeptics" and it is by Diogenes Laërtius that we attribute them to Agrippa.[9] The five tropes of Agrippa are:

- Dissent – The uncertainty demonstrated by the differences of opinions among philosophers and people in general.

- Infinite regress – All proof rests on matters themselves in need of proof, and so on to infinity.

- Relation – All things are changed as their relations become changed, or, as we look upon them from different points of view.

- Assumption – The truth asserted is based on an unsupported assumption.

- Circularity – The truth asserted involves a circularity of proofs.

According to the mode deriving from dispute, we find that undecidable dissension about the matter proposed has come about both in ordinary life and among philosophers. Because of this we are not able to choose or to rule out anything, and we end up with suspension of judgement. In the mode deriving from infinite regress, we say that what is brought forward as a source of conviction for the matter proposed itself needs another such source, which itself needs another, and so ad infinitum, so that we have no point from which to begin to establish anything, and suspension of judgement follows. In the mode deriving from relativity, as we said above, the existing object appears to be such-and-such relative to the subject judging and to the things observed together with it, but we suspend judgement on what it is like in its nature. We have the mode from hypothesis when the Dogmatists, being thrown back ad infinitum, begin from something which they do not establish but claim to assume simply and without proof in virtue of a concession. The reciprocal mode occurs when what ought to be confirmatory of the object under investigation needs to be made convincing by the object under investigation; then, being unable to take either in order to establish the other, we suspend judgement about both.[10]

With reference to these five tropes, that the first and third are a short summary of the earlier Ten Modes of Aenesidemus.[9] The three additional ones show a progress in the Pyrrhonist system, building upon the objections derived from the fallibility of sense and opinion to more abstract and metaphysical grounds. According to Victor Brochard "the five tropes can be regarded as the most radical and most precise formulation of skepticism that has ever been given. In a sense, they are still irresistible today."[11]

سمات الفعل

Pyrrhonist decision making is made according to what the Pyrrhonists describe as the criteria of action holding to the appearances, without beliefs in accord with the ordinary regimen of life based on:

- the guidance of nature, by which we are naturally capable of sensation and thought

- the compulsion of the passions by which hunger drives us to food and thirst makes us drink

- the handing down of customs and laws by which we accept that piety in the conduct of life is good and impiety bad

- instruction in techne[12]

مقولات متشككة

The Pyrrhonists devised several sayings (Greek ΦΩΝΩΝ[مطلوب توضيح]) to help practitioners bring their minds to suspend judgment.[13] Among these are:

- Not more, nothing more (a saying attributed to Democritus[14])

- Non-assertion (aphasia)

- Perhaps, it is possible, maybe

- I withhold assent

- I determine nothing (Montaigne created a variant of this as his own personal motto, "Que sais-je?" – "what do I know?")

- Everything is indeterminate

- Everything is non-apprehensible

- I do not apprehend

- To every argument an equal argument is opposed

التأثير

في الفلسفة اليونانية القديمة

وكان من سخريات الأيام أن أتباع أفلاطون هم الذين وجهوا هذه الحملة على الميتافيزيقا. ذلك أن أركسلوس الذي أصبح في عام 269 ق.م. رئيس "المجمع العلمي الأوسط" حول رفض أفلاطون للمعلومات المستمدة من الحواس إلى تشكك كامل يضارع في ذلك تشكك ديون، ولعلهم فعلوا ذلك بتأثير بيرون نفسه. ومن أقوال أركسلاوس في هذا المعنى: "لا شيء مؤكد، حتى ذلك القول نفسه(11)". ولما قيل له إن هذه العقيدة تجعل الحياة مستحيلة قال إن الحياة قد عرفت من زمن بعيد كيف تدبر أمرها بالاحتمالات. وقام على رأس "المجمع العلمي الجديد" بعد قرن من الزمان رجل كان أكثر تشككاً من أركسيلاوس، وأوصل عقيدة التشكك العام إلى العدمية الذهنية والأخلاقية، ونعني بذلك الرجل قرنيادس القوريني Carneades of Cyrene. فقد جاء هذا الأبلار اليوناني إلى أثينة حوالي عام 193، ونغص الحياة على كريسپوس Chrysippus وغيره من معلميه، بحججه الدقيقة المؤلمة ضد كل عقيدة يعلمونها. وإذ كانوا يبغون أن يجعلوه عالماً منطقياً، فقد اعتاد أن يقول لهم موجهاً قوله إلى پروتاگوراس: "إذا كان منطقي صحيحاً فبها ونعمت، وإذا كان خطأ فأعيدوا إلي ما أديته من الأجر لتعليمي(12)". ولما أنشأ لنفسهِ حانوتاً كان يحاضر في صباح يوم ما فيحبذ رأياً من الآراء، وفي اليوم التالي يحبذ نقيضه، ويبرهن على صحة كليهما بحيث يقضي عليهما جميعاً، بينما كان تلاميذه، وكاتب سيرته نفسه، يحاولون عبثاً أن يعرفوا آراءه الحقيقية. وأخذ على عاتقهِ أن يفند واقعية الرواقيين المادية ببحثهِ التحليلي الأفلاطوني- الكانتي في الحواس والعقل.

وهاجم كل النتائج المنطقية ووصفها بأنها لا يستطاع الدفاع عنها عقلياً، وأمر طلابه أن يقنعوا بالاحتمالات ويرضوا بعادات زمانهم. ولما أرسلته أثينة ضمن بعثة سياسية إلى رومة (155) أدهش مجلس الشيوخ بأن خطب في يوم من الأيام مدافعاً عن العدالة، ثم خطب في اليوم التالي مستهزئاً بها وواصفاً إياها بأنها حلم غير عملي وقال: إذا شاءت رومة أن تتبع طريق العدالة فعليها أن تعيد إلى أمم البحر المتوسط كل ما أخذته منها بفضل تفوقها عليها في القوة(13). وفي اليوم الثالث اضطر كاتو أن يعيد البعثة إلى بلدها لأنها خطر على الأخلاق العامة. وربما كان پولبيوس- وكان وقتئذ رهينة عند سبيو- قد سمع هاتين الخطبتين أو سمع عنهما، لأنه يندد تنديد الرجل العملي بأولئك الفلاسفة.

"الذين دربوا أنفسهم في مناقشات المجمع العلمي على الإفراط في الاستعداد للخطابة. ذلك أن بعضهم يلجئون إلى أشد الأشياء تناقضاً فيما يبذلون من جهد ليحيروا عقول سامعيهم، وأنهم برعوا في اختراع ما يبررون به هذه المتناقضات، حتى أنك تراهم يتناقشون وهم حيارى لا يدرون هل يستطيع من في أثينة أن يشموا رائحة البيض الذي يغلي في إفسوس أو لا يستطيعون أن يشموها، ويظنون طوال الوقت الذي يناقشون فيه مسألة في المجمع العلمي أنهم يكونون نائمين في بيوتهم يؤلفون خطبهم في أحلامهم... وقد سوءوا سمعة الفلسفة جميعاً بهذا الحب المفرط للمتناقضات... وغرسوا في عقول شبابنا هذا الحب الشديد، فكان من أثرهِ أن أولئك الشبان لا يفكرون أقل تفكير في المسائل الأخلاقية والسياسية التي تفيد طلاب الفلسفة بحق، بل تراهم يقضون وقتهم في محاولات عديمة الجدوى لاختراع السخافات والأباطيل التي لا نفع فيها".

التشابه بين الپيرونية والفلسفة الهندية

A number of similarities have been noted between the Pyrrhonist works of Sextus Empiricius and that of Nagarjuna, the Madhyamaka Buddhist philosopher from the 2nd or 3rd century CE.[15] Buddhist philosopher Jan Westerhoff says "many of Nāgārjuna's arguments concerning causation bear strong similarities to classical sceptical arguments as presented in the third book of Sextus Empiricus's Outlines of Pyrrhonism,"[16] and Thomas McEvilley suspects that Nagarjuna may have been influenced by Greek Pyrrhonist texts imported into India.[17] McEvilley argues for mutual iteration in the Buddhist logico-epistemological traditions between Pyrrhonism and Madhyamika:

An extraordinary similarity, that has long been noticed, between Pyrrhonism and Mādhyamaka is the formula known in connection with Buddhism as the fourfold negation (Catuṣkoṭi) and which in Pyrrhonic form might be called the fourfold indeterminacy.[18]

McEvilley also notes a correspondence between the Pyrrhonist and Madhyamaka views about truth, comparing Sextus' account[19] of two criteria regarding truth, one which judges between reality and unreality, and another which we use as a guide in everyday life. By the first criteria, nothing is either true or false, but by the second, information from the senses may be considered either true or false for practical purposes. As Edward Conze[20][التحقق مطلوب] has noted, this is similar to the Madhyamika Two Truths doctrine, a distinction between "Absolute truth" (paramārthasatya), "the knowledge of the real as it is without any distortion,"[21] and "Truth so-called" (saṃvṛti satya), "truth as conventionally believed in common parlance.[21][22]

Other similarities between Pyrrhonism and Buddhism include a version of the tetralemma among the Pyrrhonist maxims, and more significantly, the idea of suspension of judgement and how that can lead to peace and liberation; ataraxia in Pyrrhonism and nirvāṇa in Buddhism.[23][24]

Some scholars have also looked farther back, to determine if any earlier Indian philosophy have had an influence on Pyrrho. Diogenes Laërtius' biography of Pyrrho reports that Pyrrho traveled with Alexander the Great's army to India and incorporated what he learned from the Gymnosophists and the Magi that he met in his travels into his philosophical system.[25] Pyrrho would have spent about 18 months in Taxila as part of Alexander the Great's court during Alexander's conquest of the east.[26] Christopher I. Beckwith[27] draws comparisons between the Buddhist three marks of existence and the concepts outlined in the "Aristocles Passage".[28]

However, other scholars, such as Stephen Batchelor[29] and Charles Goodman[30] question Beckwith's conclusions about the degree of Buddhist influence on Pyrrho. Conversely, while critical of Beckwith's ideas, Kuzminsky sees credibility in the hypothesis that Pyrrho was influenced by Buddhism, even if it cannot be safely ascertained with our current information.[31]

Ajñana, which upheld radical skepticism, may have been a more powerful influence on Pyrrho than Buddhism. The Buddhists referred to Ajñana's adherents as Amarāvikkhepikas or "eel-wrigglers", due to their refusal to commit to a single doctrine.[32] Scholars including Barua, Jayatilleke, and Flintoff, contend that Pyrrho was influenced by, or at the very least agreed with, Indian skepticism rather than Buddhism or Jainism, based on the fact that he valued ataraxia, which can be translated as "freedom from worry".[33][34][35] Jayatilleke, in particular, contends that Pyrrho may have been influenced by the first three schools of Ajñana, since they too valued freedom from worry.[36]

العصر الحديث

The recovery and publication of the works of Sextus Empiricus, particularly a widely influential translation by Henri Estienne published in 1562,[37] ignited a revival of interest in Pyrrhonism.[37] Philosophers of the time used his works to source their arguments on how to deal with the religious issues of their day. Major philosophers such as Michel de Montaigne, Marin Mersenne, and Pierre Gassendi later drew on the model of Pyrrhonism outlined in Sextus Empiricus' works for their own arguments. This resurgence of Pyrrhonism has sometimes been called the beginning of modern philosophy.[37] Montaigne adopted the image of a balance scale for his motto,[38] which became a modern symbol of Pyrrhonism.[39][40] It has also been suggested that Pyrrhonism provided the skeptical underpinnings that René Descartes drew from in developing his influential method of Cartesian doubt and the associated turn of early modern philosophy towards epistemology.[37] In the 18th century, David Hume was also considerably influenced by Pyrrhonism, using "Pyrrhonism" as a synonym for "skepticism."[41][مطلوب مصدر أفضل].

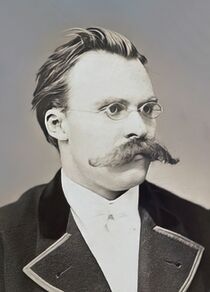

Friedrich Nietzsche, however, criticized the "ephectics" of the Pyrrhonists as a flaw of early philosophers, whom he characterized as "shy little blunderer[s] and milquetoast[s] with crooked legs" prone to overindulging "his doubting drive, his negating drive, his wait-and-see ('ephectic') drive, his analytical drive, his exploring, searching, venturing drive, his comparing, balancing drive, his will to neutrality and objectivity, his will to every sine ira et studio: have we already grasped that for the longest time they all went against the first demands of morality and conscience?"[42]

الزمن المعاصر

The term "neo-Pyrrhonism" is used to refer to modern Pyrrhonists such as Benson Mates and Robert Fogelin.[43][44]

انظر أيضاً

- Apophasis

- Apophatic theology

- Cognitive closure (philosophy)

- Cratylism

- De Docta Ignorantia

- Defeatism

- Quietism

- Buddhism and the Roman world

- Greco-Buddhism

- Ancient Greece–Ancient India relations

- E-Prime

- Aenesidemus

- Agrippa the Skeptic

- Apophasis

- Apophatic theology

- أركسيلاوس

- Quietism

- Epoche

- Sextus Empiricus

- تيمون

- Benson Mates

- نسيم طالب

- Trivialism

- The Hedgehog and the Fox

- List of unsolved problems in philosophy

الهامش

- ^ Warren, James (2002). Epicurus and Democritean ethics: An archaeology of ataraxia. Cambridge University Press. p. I. ISBN 0521813697.

- ^ Pulleyn, William (1830). The Etymological Compendium, Or, Portfolio of Origins and Inventions. T. Tegg. pp. 353.

- ^ Bett, Richard Arnot Home (Jan 28, 2010). The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Scepticism. Cambridge University Press. p. 212.

- ^ Bett, Richard Arnot Home (2010-01-28). The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Scepticism. Cambridge University Press. p. 213.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:0 - ^ McInerny, Ralph (1969). A History of Western Philosophy, Volume 2. Aeterna Press. pp. Chp III. Skeptics and the New Academy, A. Pyrrho of Elis section, para 3–4.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 1 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 257–258.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Sextus Empiricus, Outlines of Pyrrhonism, Trans. R.G. Bury, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1933, pp. 25–27

- ^ أ ب Diogenes Laërtius, ix.

- ^ Sextus Empiricus, Pyrrhōneioi hypotypōseis i., from Annas, J., Outlines of Scepticism Cambridge University Press. (2000).

- ^ Brochard, V., The Greek Skeptics.

- ^ Sextus Empiricus, Outlines of Pyrrhonism Book I Chapter 11 Section 23

- ^ Sextus Empiricus Outlines of Pyrrhonism Book I Chapter 18

- ^ Sextus Empiricus Outlines of Pyrrhonism Book II Chapter 30

- ^ Conze, Edward. Buddhist Philosophy and Its European Parallels. Philosophy East and West 13, p.9-23, no.1, January 1963. University press of Hawaii.

- ^ Jan Westerhoff Nagarjuna's Madhyamaka: A Philosophical Introduction ISBN 0195384962 2009 p93

- ^ Thomas McEvilley, The Shape of Ancient Thought 2002 pp499-505

- ^ McEvilley, Thomas (2002). The Shape of Ancient Thought. Allworth Communications. ISBN 1-58115-203-5., p.495

- ^ Sextus Empiricus, Outlines of Pyrrhonism, II.14–18; Anthologia Palatina (Palatine Anthology), VII. 29–35, and elsewhere

- ^ Conze 1959, pp. 140–141

- ^ أ ب Conze (1959: p. 244)

- ^ McEvilley, Thomas (2002). The Shape of Ancient Thought. Allworth Communications. ISBN 1-58115-203-5., p. 474

- ^ Sextus Empricus, Outlines of Pyrrhonism Book 1, Section 19

- ^ Hanner, Oren (2020). Buddhism and Scepticism: Historical, Philosophical and Comparative Perspectives. Projekt Verlag. pp. 126–129. ISBN 978-3-89733-518-9.

- ^ قالب:Cite LotEP

- ^ Adrian Kuzminski, Pyrrhonism: How the Ancient Greeks Reinvented Buddhism 2008

- ^ Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia (PDF). Princeton University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9781400866328.

- ^ Bett, Richard; Zalta, Edward (Winter 2014). "Pyrrho". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ Stephen Batchelor "Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's encounter with early Buddhism in central Asia", Contemporary Buddhism, 2016, pp 195-215

- ^ Charles Goodman, "Neither Scythian nor Greek: A Response to Beckwith's Greek Buddha and Kuzminski's "Early Buddhism Reconsidered"", Philosophy East and West, University of Hawai'i Press Volume 68, Number 3, July 2018 pp. 984-1006

- ^ Kuzminski, Adrian (2021). Pyrrhonian Buddhism: A Philosophical Reconstruction. Routledge. ISBN 9781000350074.

- ^ Jayatilleke, K.N. Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge. George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London, p. 122.

- ^ Barua 1921, p. 299.

- ^ Jayatilleke 1963, pp. 129-130.

- ^ Flintoff 1980.

- ^ Jayatilleke 1963, pp. 130.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Popkin, Richard Henry (2003). The History of Scepticism : from Savonarola to Bayle (Revised ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198026716. OCLC 65192690.

- ^ Sarah Bakewell, How to Live: Or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer 2011 p 127 ISBN 1590514831

- ^ Kraye, Jill; Saarinen, Risto (2006-03-30). Moral Philosophy on the Threshold of Modernity (in الإنجليزية). Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-3001-7.

- ^ Sextus (Empiricus.) (1985-01-01). Selections from the Major Writings on Scepticism, Man, & God (in الإنجليزية). Hackett Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87220-006-7.

- ^ Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, page 7, section 23.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche; Maudemarie Clark; Alan J. Swensen (1998). On the Genealogy of Morality. Hackett Publishing. p. 79.

- ^ Michael Williams, "Fogelin's Neo-Pyrrhonism", International Journal of Philosophical Studies Volume 7, Issue 2, 1999, p141

- ^ Smith, Plínio Junqueira; Bueno, Otávio (7 May 2016). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Skepticism in Latin America. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

وصلات خارجية

- Ancient Skepticism entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy by Leo Groarke

- Ancient Greek Skepticism entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy by Harold Thorsrud

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Wikipedia articles incorporating text from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from April 2025

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج تمحيص الحقائق from February 2024

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تمحيص حقائق

- كل المقالات بدون مراجع موثوقة

- كل المقالات بدون مراجع موثوقة from January 2023

- نظريات معرفية

- فلسفة هلينية

- حركات فلسفية

- شكوكية

- Pyrrhonism

- Philosophical skepticism

- تأسيسات القرن الأول ق.م.