نوڤاليس Novalis

نوڤاليس Novalis | |

|---|---|

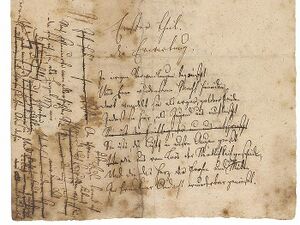

Novalis (1799), portrait by Franz Gareis | |

| وُلِد | 2 مايو 1772 Wiederstedt, Electorate of Saxony, Holy Roman Empire |

| توفي | 25 مارس 1801 (aged 28) Weissenfels, Electorate of Saxony |

| الوظيفة | كاتب نثر، شاعر، صوفي، فيلسوف، مهندس مدني |

| العرق | ألماني |

| الجامعة الأم | University of Jena Leipzig University University of Wittenberg Mining Academy of Freiberg |

| الفترة | 1791–1801 |

| الصنف الأدبي |

|

| الموضوع |

|

| الحركة الأدبية | رومانسية ينا[1] |

| التوقيع |  |

نوڤاليس Novalis هو البارون جورج فريدريش فرايهر فون هاردنبرگ Friedrich Leopold von Hardenberg (2 مايو 1772 - 25 مارس 1801)، وقد صاغ اسمه المستعار من الاسم القديم دي نوڤالي de Novali الذي كانت تستخدمه عائلته الأرستقراطية. ولد في بلدة أوبرڤيدرشتت Oberwiederstedt؛ وتُوفِّي في مدينة ڤايسنفلز Weissenfels التابعتين لإمارة سكسونيا Sachsen الألمانية، وهو شاعر وروائي وكاتب مقالات من أبرز وجوه الحركة الرومانسية Romantik الألمانية. نشأ في عائلة بروتستانتية تقية، وبدأ - بعد إنهاء التعليم المدرسي- بدراسة الفلسفة في جامعة يينا Jena عام 1790، ثم انتقل بين عامي 1791-1793 إلى مدينتي لايبزيغ وڤيتنبِرگ Wittenberg حيث درس الحقوق. وعلى أثر وفاة حبيبته وخطيبته صوفي فون كون Sophie von Kühn ذات الخمسة عشر ربيعاً بالسل في مطلع عام 1797 مرَّ نوڤاليس بتجربة عاطفية وفكرية عميقة أثرت في إبداعه الأدبي على نحو جلي، فانتقل إلى ڤايسنفلز، وصار يتردد على أجواء الرومانسيين الأوائل في يينا، من مثل ڤيلهلم ڤاكنرودر W.Wackenroder ولودڤيگ تيك Tieck والأخوين شليگل Schlegel والفيلسوف يوهان جوتليب فيخته J.G.Fichte. وبين عامي 1797- 1798 درس نوڤاليس علم المناجم في أكاديمية فرايبرگ Freiberg، وعُيِّن مشرفاً على موظفي ملاّحة ڤايسنفلز وعمالها.

السيرة

يُعدّ نوڤاليس من أهم أدباء الرومانسية الألمانية المبكرة التي تحمست بدايةً للثورة الفرنسية (1789)، ومجَّدت شعاراتها المعلنة (حرية، مساواة، أخوة)، ولكن منذ عام 1798/1799 بدأت تظهر آثار خيبة الأمل وانكسار الأحلام تجاه النتائج التاريخية للثورة التي رسخت أركان المجتمع البرجوازي على حساب شعاراتها ومبادئ معركتها الاجتماعية - الاقتصادية - الثقافية. وبما أن مثال الإنسانية المبدِعة المحرِّرة لم يعد قابلاً للتحقيق في حيز الواقع، فلابد من رفعه إلى حيز الشعر، لكون الشعر المجال الوحيد لفعالية غير مُستلَبة في رأي الرومنسيين الأوائل. وهذا الميل نحو التكثيف الروحاني مع تأسيس مفاهيم الشعر الرومنسية قد تجليا في مجموعتي الشذرات: الأولى «غبار الطلع» Blütenstaub ت(1798) والثانية «إيمان وحب» Glauben und Liebe ت(1798) اللتين تضمنتا آراءه الفلسفية الجمالية والاجتماعية السياسية من منظور مثالي ذي مرجعيات مختلفة، كما تبدى فيهما توقه إلى «عصر ذهبي» يحل فيه انسجام تام بين البشر، وتنتفي المشكلات في ظل كنيسة شاملة لا مذاهب فيها ولا طوائف، مثلما كان الوضع في العصر الوسيط. إن إبداع نوڤاليس الشعري الذي يمتزج فيه إشراقه الصوفي الأُخروي ببهجته الدنيوية كان متزامناً مع انهماكه في أداء واجبه الوظيفي بإخلاص وتفانٍ ومع استغراقه في دراسات العلوم الطبيعية واللاهوت، وكان تعبيراً خالصاً عن المفاهيم الفنية والفكرية الرومنسية المبكرة، عن «مثالية سحرية» magischer Idealismus تجسد عالماً منسجماً متكاملاً على نحو طوباوي يعلو على الواقع الحقيقي، ويتعارض من ثم مع مفاهيم الواقعية الاجتماعية gesellschaftlicher Realismus التي طورتها الكلاسيكية الألمانية بريادة گوته وشيلر وغيرهما. وفي هذا السياق يندرج ديوانه المهم «تراتيل إلى الليل» Hymnen an die Nacht (نُظم عام 1797 ونُشر عام 1800 في مجلة «أتِِنيوم» Athenäum) الذي نظم قصائده الست بإحساس عميق ولغة إيقاعية سامية صدوراً عن يأسه من موت حبيبته المبكر. ففي قصائد هذا الديوان - النثرية والشعرية معاً- يضع نوڤاليس الموت والمرض و«ملكوت الليل الأبدي العجيب» في مواجهة الحياة والوجود الدنيوي ويرفعهم إلى مستوى دين للموت Todesreligion. وفي عام 1799 نظم الشاعر مجموعة «أغان دينية» Geistliche Lieder تجلى في لغتها الشعبية البسيطة والحميمية الجميلة مدى ابتعاد الشاعر عن التفكير الفلسفي وتحوله المندفع نحو العقيدة الكاثوليكية، (نشر الديوان عام 1802 في «أتنيو»). وفي نهاية عام 1799 خطب نوڤاليس يولي فون كاربنتير Julie von Charpentier التي لم يستطع أيضاً أن يتزوجها بسبب موته المبكر.

ڤايسنفلز: السنوات الأخيرة

لكن سنوات حياته الأخيرة كانت غزيرة الإنتاج الأدبي، فقد كتب نوڤاليس في أثنائها رواية «المتدربون في زايس» Die Lehrlinge zu Sais (نشرت ضمن المؤلفات الكاملة عام 1802) التي عرض فيها آراءه في علاقة الإنسان بالطبيعة، وكيف يمكن للإنسان المحب العارف أن يكتشف ذاته من خلال جهوده لاكتشافها والكشف عن جوهرها. والرواية في جزأيها مزيج من الحوارات العلمية والتأملات والحكايات الخرافية الجميلة ذات الهدف التعليمي «أمثولات». كما كتب في هذه المرحلة روايته الشهيرة «هاينريش فون أوفتردينگن» Heinrich von Ofterdingen (نشرت ضمن المؤلفات الكاملة عام 1802) التي قصد بها معارضة رواية گوته التربوية «سنوات تعلُّم ڤيلهلم مايستر» Die Lehrjahre des Wilhelm Meisters. وقد صاغ نوڤاليس روايته بلغة شاعرية إيقاعية في أجواء حكاية خرافية حول المغني الجوال (مينزِنگر) Minnesänger الأسطوري هاينريش من العصر الوسيط ومراحل تعلمه بحثاً عن «الزهرة الزرقاء» Die blaue Blume التي صارت رمزاً للحركة الرومنسية مؤكداً فيها معارضة الواقع النثري الجاف المقيت بعالم الشعر الذي منحه المؤلف قوى سحرية تساعد الإنسان على انعتاق روحه وتحرير ذاته. وقد بقيت الروايتان غير مكتملتين. وكان آخر أعماله مقالة «المسيحية أو أوربا» Christenheit oder Europa التي لم تنشر قبل 1826، وهي رثاء لانقسام المسيحية الأوربية بسبب حركة الإصلاح اللوثرية وعصر التنوير Aufklärung، واستحضارٌ لعصر ديني جديد يعيش الناس فيه بنعيم وسلام، ولكن في مستقبل قادم طوباوي الملامح، وهذا على نقيض تمجيده في أعماله السابقة لصورته عن العصر الوسيط الذهبي.[2]

الذكرى

كشاعر رومانسي

When he died, Novalis had only published Pollen, Faith and Love, Blumen, and Hymns to the Night. Most of Novalis's writings, including his novels and philosophical works, were neither completed nor published in his lifetime. This problem continues to obscure a full appreciation of his work.[4] His unfinished novels Heinrich von Ofterdingen and The Novices at Sais and numerous other poems and fragments were published posthumously by Ludwig Tieck and Friedrich Schlegel. However, their publication of Novalis's more philosophical fragments was disorganized and incomplete. A systematic and more comprehensive collection of Novalis's fragments from his notebooks was not available until the twentieth century.[5]

During the nineteenth century, Novalis was primarily seen as a passionate love-struck poet who mourned the death of his beloved and yearned for the hereafter.[6] He was known as the poet of the blue flower, a symbol of romantic yearning from Novalis's unfinished Novel Heinrich von Ofterdingen that became an key emblem for German Romanticism.[7] His fellow Jena Romantics, such as Friedrich Schlegel, Tieck, and Schleiermacher, also describe him as a poet who dreamt of a spiritual world beyond this one.[8] Novalis's diagnosis of tuberculosis, which was known as the white plague, contributed to his romantic reputation.[7] Because Sophie von Kühn was also thought to have died from tuberculosis, Novalis became the poet of the blue flower who was reunited with his beloved through the death of the white plague.[9]

The image of Novalis as romantic poet became enormously popular. When Novalis's biography by his long-time friend August Cölestin Just was published in 1815, Just was criticized for misrepresenting Novalis's poetic nature because he had written that Novalis was also a hard-working mine inspector and magistrate.[10] Even the literary critic Thomas Carlyle, whose essay on Novalis played a major role in introducing him to the English-speaking world and took Novalis's philosophical relationship to Fichte and Kant seriously,[11] emphasized Novalis as a mystic poet in the style of Dante.[12] The author and theologian George MacDonald, who translated Novalis's Hymns to the Night in 1897 into English,[13] also understood him as a mystic poet.[14]

كمفكر فلسفي

In the twentieth century, Novalis's writings were more thoroughly and systematically collected than previously. The availability of these works provide further evidence that his interests went beyond poetry and novels and has led to a reassessment of Novalis's literary and intellectual goals.[15] He was deeply read in science, law, philosophy, politics and political economy and left an abundance of notes on these topics. His early work displays his ease and familiarity with these diverse fields. His later works also include topics from his professional duties. In his notebooks, Novalis also reflected on the scientific, aesthetic, and philosophical significance of his interests. In his Notes for a Romantic Encyclopaedia, he worked out connections between the different fields he studied as he sought to integrate them into a unified worldview.[16]

Novalis's philosophical writings are often grounded in nature. His works explore how personal freedom and creativity emerge in the affective understanding of the world and others. He suggests that this can only be accomplished if people are not estranged from the earth.[17] In Pollen, Novalis writes "We are on a mission: Our calling is the cultivation of the earth",[18] arguing that human beings come to know themselves through experiencing and enlivening nature.[17] Novalis's personal commitment to understanding one's self and the world through nature can be seen in Novalis's unfinished novel, Heinrich von Ofterdingen, in which he uses his knowledge of natural science derived from his work overseeing salt mining to understand the human condition.[19] Novalis's commitment to cultivating nature has even been considered as a potential source of insight for a deeper understanding of the environmental crisis.[20]

Magical idealism

Novalis's personal worldview—informed by his education, philosophy, professional knowledge, and pietistic background—has become known as magical idealism, a name derived from Novalis's reference in his 1798 notebooks to a type of literary prophet, the magischer Idealist (magical idealist).[22] In this worldview, philosophy and poetry are united.[23] Magical idealism is Novalis's synthesis of the German idealism of Fichte and Schelling with the creative imagination.[24] The goal of the creative imagination is to break down the barriers between language and world, as well as the subject and object.[22] The magic is the enlivening of nature as it responds to our will.[23]

Another element of Novalis's magical idealism is his concept of love. In Novalis's view, love is a sense of relationship and sympathy between all beings in the world,[24] which is considered both the basis of magic and its goal.[23] From one perspective, Novalis's emphasis on the term magic represents a challenge to what he perceived as the disenchantment that came with modern rationalistic thinking.[25] From another perspective, however, Novalis's use of magic and love in his writing is a performative act that enacts a key aspect of his philosophical and literary goals. These words are meant to startle readers into attentiveness, making them aware of his use of the arts, particularly poetry with its metaphor and symbolism, to explore and unify various understandings of nature in his all-embracing investigations.[26]

Magical idealism also addresses the idea of health.[24] Novalis derived his theory of health from the Scottish physician John Brown's system of medicine, which sees illness as a mismatch between sensory stimulation and internal state.[27] Novalis extends this idea by suggesting that illness arises from a disharmony between the self and the world of nature.[24] This understanding of health is immanent: the "magic" is not otherworldly, it is based on the body and mind's relationship to the environment.[28] According to Novalis, health is maintained when we use our bodies as means to sensitively perceive the world rather than to control the world: the ideal is where the individual and the world interplay harmoniously.[29] It has been argued that there is an anxiety in Novalis's sense of magical idealism that denies actual touch, which leads inevitably to death, and replaces it with an idea of "distant touch".[30]

آراء دينية

Novalis's religious perspective remains a subject of debate. Novalis's early rearing in a Pietist household affected him through this life.[32] The impact of his religious background on his writings are particularly clear in his two major poetic works. Hymns to the Night contains many Christian symbols and themes.[33] And, Novalis's Spiritual Songs, which were posthumously published in 1802 were incorporated into Lutheran hymnals; Novalis called the poems "Christian Songs", and they were intended to be published in the Athenaeum under the title Specimens From a New Devotional Hymn Book.[33] One of his final works, which was posthumously named Die Christenheit oder Europa (Christianity or Europe) when it was first published in full in 1826, has generated a great deal of controversy regarding Novalis's religious views.[34] This essay, which Novalis himself had simply entitled Europa, called for European unity in Novalis's time by poetically referencing a mythical Medieval golden age when Europe was unified under the Catholic Church.[35]

One view of Novalis's work is that it maintains a traditional Christian outlook. Novalis's brother Karl writes that during his final illness, Novalis would read the works of the theologians Nicolaus Zinzendorf and Johann Kaspar Lavater, as well as the Bible.[36] On the other hand, during the decades following Novalis's death, German intellectuals, such as the author Karl Hillebrand and the literary critic Hermann Theodor Hettner thought that Novalis was essentially a Catholic in his thinking.[8] In the twentieth century, this view of Novalis has sometimes led to negative assessments of his work. Hymns to the Night has been described as an attempt by Novalis to use religion to avoid the challenges of modernity,[37] and Christianity or Europe has been described variously as desperate prayer, a reactionary manifesto or a theocratic dream.[34]

Another view of Novalis's work is that it reflects a Christian mysticism.[33] After Novalis died, the Jena Romantics wrote of him as a seer who would bring forth a new gospel:[8] one who lived his life as one aiming toward the spiritual while looking at death as a means of overcoming human limitation[38] in a revolutionary movement toward God.[39] In this more romantic view, Novalis was a visionary who saw contemporary Christianity as a stage to an even higher expression of religion[40] where earthly love rises to a heavenly love[41] as death itself is defeated by that love.[42] At the end of the nineteenth century, the playwright and poet Maurice Maeterlinck also described Novalis as a mystic. However, Maeterlinck acknowledged the impact of Novalis's intellectual interests on his religious views, describing Novalis as a "scientific mystic" and comparing him to the physicist and philosopher Blaise Pascal.[43]

More recently, Novalis's religious outlook has been analysed from the point of view of his philosophical and aesthetic commitments.[44] In this view, Novalis's religious thought was based on his attempts to reconcile Fichte's idealism, in which the sense of self arises in the distinction of subject and object, with Baruch Spinoza's naturalistic philosophy, in which all being is one substance. Novalis sought a single principle through which the division between ego and nature becomes mere appearance.[44] As Novalis's philosophical thinking on religion developed, it became influenced by the Platonism of Hemsterhuis, as well as the Neoplatonism of Plotinus. Accordingly, Novalis aimed to synthesize naturalism and theism into a "religion of the visible cosmos".[45] Novalis believed that individuals could obtain mystic insight, but religion can remain rational: God could be a Neoplatonic object of intellectual intuition and rational perception, the logos that structures the universe.[44] In Novalis's view, this vision of the logos is not merely intellectual, but moral too, as Novalis states "god is virtue itself".[17] This vision includes Novalis's idea of love, in which self and nature united in a mutually supportive existence.[46] This understanding of Novalis's religious project is illustrated by a quote from one of his notes in his Fichte-Studien (Fichte Studies): "Spinoza ascended as far as nature- Fichte to the 'I', or the person, I ascend to the thesis of God".[45]

According to this Neoplatonic reading of Novalis, his religious language can be understood using the "magic wand of analogy",[47] a phrase Novalis used in Europe and Christianity to clarify how he meant to use history in that essay.[48] This use of analogy was partly inspired by Schiller, who argued that analogy allows facts to be connected into a harmonious whole,[24] and by his relationship with Friedrich Schlegel, who sought to explore the revelations of religion through the union of philosophy and poetry.[49] The "magic wand of analogy" allowed Novalis to use metaphor, analogy and symbolism to bring together the arts, science, and philosophy in his search for truth.[26] This view of Novalis's writing suggests that his literary language must be read carefully. His metaphors and images- even in works like Hymns to the Night- are not only mystical utterances,[50] they also express philosophical arguments.[51] Read in this perspective, a work like Novalis's Christianity or Europe is not a call to return to a lost golden age. Rather, it is an argument in poetic language, phrased in the mode of a myth,[35] for a cosmopolitan vision of a unity[34] that brings together past and future, ideal and real, to engage the listener in an unfinished historical process.[52]

الكتابات

الشعر

Novalis is best known as a German Romantic poet.[23] His two sets of poems, Hymns to the Night and Spiritual Songs, are considered his major lyrical achievements.[5] Hymns to the Night were begun in 1797 after the death of Sophie von Kühn. About eight months after they were completed, a revised edition of the poems was published in the Athenaeum. The Spiritual Songs, which were written in 1799, were posthumously published in 1802. Novalis called the poems Christian Songs, and they were intended to be entitled Specimens From a New Devotional Hymn Book. After his death many of the poems were incorporated into Lutheran hymn-books.[33] Novalis also wrote a number of other occasional poems, which can be found in his collected works.[5] Translations of poems into English include:

- Hymns to the Night

- "Hymns to the Night". Hymns and Thoughts on Religion by Novalis. Translated by W. Hastie. Edinburgh, Scotland: T. & T. Clark. 1888. قالب:Free access

- "Hymns to the Night". Novalis: His Life, Thoughts and Works. Translated by Hope, M. J. Chicago: McClurg. 1891. قالب:Free access

- "Hymns to the Night". Rampolli. Translated by MacDonald, George. 2005 [1897] – via Project Gutenberg. قالب:Free access

- Hymns to the Night. Translated by Higgins, Dick. Kingston, NY: McPherson & Company. 1988. This modern translation includes the German text (with variants) en face.

- أغاني روحانية

- "Spiritual Songs". Hymns and Thoughts on Religion by Novalis. Translated by Hastie, W. Edinburg, Scotland: T. & T. Clark. 1888. قالب:Free access

- "Spiritual Hymns". The Disciples at Saïs and Other Fragments. Translated by F. V. M. T; U. C. B. London: Methuen. 1903. قالب:Free access

- "Spiritual Songs". Rampolli. Translated by MacDonald, George. Chicago: T. & T. Clark. 2005 [1897] – via Project Gutenberg. قالب:Free access

- Hymns to the Night/Spiritual Songs. Translated by MacDonald, George. with foreword by Prokofieff, Sergei O. London: Temple Lodge Publishing. 2001. ISBN 9780904693416.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

روايات غير مكتملة

Novalis wrote two unfinished novel fragments, Heinrich von Ofterdingen and Die Lehrlinge zu Sais (The Novices at Sais), both of which were published posthumously by Tieck and Schlegel in 1802. The novels both aim to describe a universal world harmony with the help of poetry. The Novices at Sais contains the fairy tale "Hyacinth and Rose Petal". Heinrich von Ofterdingen is the work in which Novalis introduced the image of the blue flower. Heinrich von Ofterdingen was conceived as a response to Goethe's Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship, a work that Novalis had read with enthusiasm but judged as being highly unpoetical.[43] He disliked Goethe making the economical victorious over the poetic in the narrative, so Novalis focused on making Heinrich von Ofterdingen triumphantly poetic.[53] Both of Novalis's novels also reflect human experience through metaphors related to his studies in natural history from Freiburg.[54] Translations of Novels into English include:

- Heinrich von Ofterdingen

- Henry von Ofterdingen: A Romance. Cambridge, England: John Owens. 1842. قالب:Free access (Translated by Frederick S. Stallknecht and Edward C. Sprague.) [55]

- "Heinrich von Ofterdingen". Novalis: His Life, Thoughts and Works. Translated by Hope, M. J. Chicago: McClurg. 1891. قالب:Free access

- Henry von Ofterdingen. Translated by Hilty, Palmer. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press. 1990.

- The Novices at Sais

- "The Disciples at Saïs". The Disciples at Saïs and Other Fragments. Translated by F. V. M. T; U. C. B. London: Methuen. 1903. قالب:Free access

- The Novices of Sais. Translated by Manheim, Ralph. Brooklyn, NY: Archipelago Books. 2005. This translation was originally published in 1949 and includes illustrations by Paul Klee.

شظايا

Together with Friedrich Schlegel, Novalis developed the fragment as a literary artform in German. For Schlegel, the fragment served as a literary vehicle that mediated apparent oppositions. Its model was the fragment from classical sculpture, whose part evoked the whole, or whose finitude evoked infinite possibility, via the imagination.[56] The use of the fragment allowed Novalis to easily express himself on any issue of intellectual life he wanted to address,[57] and it served as a means of expressing Schlegel's ideal of a universal "progressive universal poesy", that fused "poetry and prose into an art that expressed the totality of both art and nature".[58] This genre particularly suited Novalis as it allowed him to express himself in a way that kept both philosophy and poetry in a continuous relationship.[26] His first major use of the fragment as a literary form, Pollen, was published in the Athenaeum in 1798.[57] English translations include:

- Pollen

Writings of Novalis, Volume 2 on Wikisource This and subsequent wikisource references are translations from Minor, Jakob (1907). Novalis Schriften, Volume 2 [Writings of Novalis, Volume 2] (in الألمانية). Jena, Germany: Eugene Diederichs. pp. 110–139. This version of Pollen is the one published in the Athenaeum in 1798, which was edited by Schlegel.[59] and includes four of Schlegel's fragments in fine print.

Writings of Novalis, Volume 2 on Wikisource This and subsequent wikisource references are translations from Minor, Jakob (1907). Novalis Schriften, Volume 2 [Writings of Novalis, Volume 2] (in الألمانية). Jena, Germany: Eugene Diederichs. pp. 110–139. This version of Pollen is the one published in the Athenaeum in 1798, which was edited by Schlegel.[59] and includes four of Schlegel's fragments in fine print.

- Gelley, Alexander (1991). "Miscellaneous Remarks (Original Version of Pollen)". New Literary History. 22 (2): 383–406. doi:10.2307/469045. JSTOR 469045. قالب:Limited access قالب:Registration required This version is translated from Novalis's unpublished original manuscript.

- "Pollen". Novalis: Philosophical Writings. Translated by Stoljar, Margaret Mahoney. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. 1997. This version is also translated from Novalis's unpublished original manuscript.

الكتابات السياسية

| هذا المقال جزء من سلسلة عن |

| التيار المحافظ في ألمانيا |

|---|

|

During his lifetime, Novalis wrote two works on political themes, Faith and Love or the King and the Queen and his speech Europa, which was posthumously named Christianity or Europe. In addition to their political focus, both works share a common theme of poetically arguing for the importance of "faith and love" to achieve human and communal unification.[34] Because these works poetically address political concerns, their meaning continues to be the subject of disagreement. Their interpretations have ranged from being seen as reactionary manifestos celebrating hierarchies to utopian dreams of human solidarity.[60]

Faith and Love or the King and the Queen was published in Yearbooks of the Prussian Monarchy in 1798 just after King Wilhelm Frederick III and his popular wife Queen Louise ascended to the throne of Prussia.[57] In this work, Novalis addresses the king and queen, emphasizing their importance as role models for creating an enduring state of interconnectedness both on the individual and collective level.[61] Though a substantial portion of the essay was published, Frederick Wilhelm III censored the publication of additional installments as he felt it held the monarchy to impossibly high standards. The work is also notable in that Novalis extensively used the literary fragment to make his points.[34]

Europa was written and originally delivered to a private group of friends in 1799. It was intended for the Athenaeum; after it was presented, Schlegel decided not to publish it. It was not published in full until 1826.[34] It is a poetical, cultural-historical speech with a focus on a political utopia with regard to the Middle Ages. In this text Novalis tries to develop a new Europe which is based on a new poetical Christendom which shall lead to unity and freedom. He got the inspiration for this text from a book written by Schleiermacher, Über die Religion (On Religion). The work was a response to the French Revolution and its implications for the French enlightenment, which Novalis saw as catastrophic. It anticipated the growing German and Romantic critiques of the then-current enlightenment ideologies in the search for a new European spirituality and unity.[33] Below are some available English translations, as well as two excerpts that illustrate how Europa has variously been interpreted.

- Faith and Love or the King and the Queen

Writings of Novalis, Volume 2 on Wikisource This version follows the published version in that it treats the first six fragments as part of a prelude, so it is numbered differently than later versions. Page links in wikisource document can be used to compare the English translation to German original.

Writings of Novalis, Volume 2 on Wikisource This version follows the published version in that it treats the first six fragments as part of a prelude, so it is numbered differently than later versions. Page links in wikisource document can be used to compare the English translation to German original.

- "Faith and Love or the King and the Queen". Novalis: Philosophical Writings. Translated by Stoljar, Margaret Mahoney. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. 1997.

- "Novalis, Faith and Love". The Early Political Writings of the German Romantics. Translated by Beiser, Frederick C. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. 1996.

- Europa (posthumously named Christianity or Europe)

- "Novalis, "Christendom or Europe" [Die Christenheit oder Europa] (1799)" (PDF). German History in Documents and Images (GHDI). Translated by Passage, Charles E. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2020. قالب:Free access

- "The Future of Christendom [excerpt from Europa]". Hymns and Thoughts on Religion by Novalis. Translated by Hastie, W. Edinburg, Scotland: T. & T. Clark. 1888. قالب:Free access

- Seth, Catriona; von Kulessa, Rotrand (eds.). "Spiritual Advent [excerpt from Europa]". The Idea of Europe: Enlightenment Perspectives. Translated by Seth, Catriona. Cambridge, England: Open Book Press, 2017. JSTOR j.ctt1sq5v84.50.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link)

Collected and miscellaneous works in English

Additional works that have been translated into English are listed below. Most of the works reflect Novalis's more philosophical and scientific sides, most of which were not systematically collected, published, and translated until the 20th century. Their publication has called for a reassessment of Novalis and his role as a thinker as well as an artist.[59]

- Philosophical and political works

- "Monologue". Earlham College. Translated by Güven, Fervit. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. قالب:Free access In Monologue, Novalis discuss the limits and nature of language.[62]

Writings of Novalis, Volume 2 on Wikisource This translation of Jacob Minor's version of Novalis's collected works includes Pollen, Faith and Love or the King and Queen, and Monologue. It also includes Klarisse, Novalis's brief description Sophie von Kühn.

Writings of Novalis, Volume 2 on Wikisource This translation of Jacob Minor's version of Novalis's collected works includes Pollen, Faith and Love or the King and Queen, and Monologue. It also includes Klarisse, Novalis's brief description Sophie von Kühn.

- Bernstein, Jay, ed. (2003). Classic and Romantic German Aesthetics. Translated by Crick, Joyce P. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. This collection contains a selection of Novalis's fragments, as well as his work Dialogues. This volume also has collections of fragments by Friedrich Schlegel and Hölderlin.

- Stoljar, Margaret Mahoney, ed. (1997). Novalis: Philosophical Writings. Translated by Stoljar, Margaret Mahoney. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. This volume contains several of Novalis' works, including Pollen or Miscellaneous Observations, one of the few complete works published in his lifetime (though it was altered for publication by Friedrich Schlegel); Logological Fragments I and II; Monologue, a long fragment on language; Faith and Love or The King and Queen, a collection of political fragments also published during his lifetime; On Goethe; extracts from Das allgemeine Broullion or General Draft; and his essay Christendom or Europe.

- Beiser, Frederick C., ed. (1996). The Early Political Writings of the German Romantics. Translated by Beiser, Frederick C. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. This volume includes Pollen, Faith and Love or the King and Queen, Political Aphorisms, Christianity or Europe: A Fragment. It also has works by Friedrich Schlegel and Schleiermacher.

- Notebooks

- Kellner, Jane, ed. (2003). Fichte Studies. Translated by Kellner, Jane. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. This book is in the same series as the Classic and Romantic German Aesthetics. Contains Novalis's notes as he read and responded to Fichte's The Science of Knowledge.

- Wood, David W., ed. (2007). Novalis: Notes for a Romantic Encyclopaedia (Das Allgemeine Brouillon). Translated by Wood, David W. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.(The first 50 of the 1151 entries are available online قالب:Free access.) This is an English translation of Novalis's unfinished project for a "universal science". It contains his thoughts on philosophy, the arts, religion, literature and poetry, and his theory of "Magical Idealism". The Appendix contains substantial extracts from Novalis' Freiberg Natural Scientific Studies 1798/1799.

- Journals

- Donehower, Bruce., ed. (2007). The Birth of Novalis: Friedrich von Hardenberg's Journal of 1797, with Selected Letters and Documents. Translated by Donehower, Bruce. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. This book includes Novalis's letters and journals around the time of Sophie's illness, as well as early biographies on Novalis.

أعمال مجمعة (بالألمانية)

Novalis's works were originally issued in two volumes by his friends Ludwig Tieck and Friedrich Schlegel (2 vols. 1802; a third volume was added in 1846). Editions of Novalis's collected works have since been compiled by C. Meisner and Bruno Wille (1898), by Ernst Heilborn (3 vols., 1901), and by J. Minor (4 vols., 1907). Heinrich von Ofterdingen was published separately by J. Schmidt in 1876.[63] The most current version of Novalis's collected works, a German-language, six-volume edition of Novalis works Historische-Kritische Ausgabe - Novalis Schriften (HKA), is edited by Richard Samuel, Hans-Joachim Mähl & Gerhard Schulz. It is published by Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart, 1960–2006.

- Novalis's Collected Works (Available online.)

- Novalis Schriften (Novalis's Writings) (edited by Ludwig Tieck and Friedrich Schlegel; in German with Fraktur font), Berlin, Germany: G. Reimer, 1837 (fifth edition). This is the collection that originally established Novalis's reputation.

- Novalis Schriften (edited by Jakob Minor; in German with Fraktur font) Jena, Germany: Eugene Diederiche, 1907. This a more comprehensive and better organized collection than Tieck and Schlegel's.

Novalis's Correspondence was edited by J. M. Raich in 1880. See R. Haym Die romantische Schule (Berlin, 1870); A. Schubart, Novalis' Leben, Dichten und Denken (1887); C. Busse, Novalis' Lyrik (1898); J. Bing, Friedrich von Hardenberg (Hamburg, 1899), E. Heilborn, Friedrich von Hardenberg (Berlin, 1901).[63]

الأثر

The political philosopher Karl Marx's metaphorical argument that religion was the opium of the people was prefigured by Novalis's statement in Pollen where he describes "philistines" with the following analogy, "Their so-called religion works just like an opiate: stimulating, sedating, stilling pain through innervation".[64]

Hungarian philosopher György Lukács derived his concept of philosophy as transcendental homelessness from Novalis. In his 1914–15 essay Theory of the Novel quotes Novalis at the top of the essay, "Philosophy is really homesickness—the desire to be everywhere at home."[65] The essay unfolds closely related to this notion of Novalis—that modern philosophy "mourns the absence of a pre-subjective, pre-reflexive anchoring of reason"[66] and is searching to be grounded but cannot achieve this aim due to philosophy's modern discursive nature. Later, however, Lukács repudiated Romanticism, writing that Novalis's "cult of the immediate and the unconscious necessarily leads to a cult of night and death, of sickness and decay."[67]

The musical composer Richard Wagner's libretto for the opera Tristan und Isolde contains strong allusions to Novalis's symbolic language,[68] especially the dichotomy between the Night and the Day that animates his Hymns to the Night.[69]

The literary critic Walter Pater includes Novalis's quote, "Philosophiren ist dephlegmatisiren, vivificiren" ("to philosophize is to throw off apathy, to become revived")[70] in his conclusion to Studies in the History of the Renaissance.

The esotericist and philosopher Rudolf Steiner spoke in various lectures (now published) about Novalis and his influence on anthroposophy.[71]

The literary critic, philosopher and photographer's Franz Roh term magischer Realismus that he coined in his 1925 book Nach-Expressionismus, Magischer Realismus: Probleme der neuesten europäischen Malerei (Post-expressionism, Magic Realism: Problems in Recent European Painting) may have been inspired by Novalis's term magischer Realist.[27]

André Breton and the Surrealists were greatly influenced by Novalis.[72] Breton cited Novalis extensively in his study of art history, L'Art Magique, as well.

The 20th-century philosopher Martin Heidegger uses a Novalis fragment, "Philosophy is really homesickness, an urge to be at home everywhere" in the opening pages of The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics.[73]

The UK Charity "Novalis Trust" which provides care and education for individuals with additional needs.[74]

The author Hermann Hesse's writing was influenced by Novalis's poetry,[75] and Hesse's last full-length novel Glasperlenspiel (The Glass Bead Game) contains a passage that appears to restate one of the fragments in Novalis's Pollen.[76]

The artist and activist Joseph Beuys's aphorism "Everyone is an artist" was inspired by Novalis,[77] who wrote "Every person should be an artist" in Faith and Love or the King and the Queen.

The author Jorge Luis Borges refers often to Novalis in his work.[22]

The krautrock band Novalis took their name from Novalis and used his poems for lyrics on their albums.

Novalis records, which are produced by AVC Audio Visual Communications AG, Switzerland, was named in tribute to Novalis's writings.

The avant-garde filmmaker Stan Brakhage made the short film First Hymn to the Night – Novalis in 1994. The film, which visually incorporates the text of Novalis's poem, was issued on Blu-ray and DVD in an anthology of Brakhage's films by Criterion Collection.

The artist and animator Chris Powell created the award-winning animated film Novalis. The title character is a robot named after Novalis.

Novalis has also influenced film theory by way of Jacques Rancière, who employs various elements of German Idealism and Romanticism in his philosophical work on critical philosophy and the regimes of art.[78]

The composer, guitarist, and electronic music artist Erik Wøllo titled one of his songs "Novalis".

Penelope Fitzgerald based her historical novel The Blue Flower on Novalis's love affair with Sophie and her influence on his art.

الهوامش

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRedfield2012 - ^ نبيـل الحفـار. "نوڤاليس (1772 ـ 1801)". الموسوعة العربية.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةLittlejohns2003 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةWood2002 - ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMason1961 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHaase1979 - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRobles2020 - ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHaussmann1912 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBarroso2019 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةDonehower2007 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHarrold1930 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةCarlyle1829 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMacDonald1897 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةPartridge2014 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةZiolkowski1996 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةKneller2008 - ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةNassar2013 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةGelley1991b - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةErlin2014 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBecker&Manstetten2004 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةGHDI2003 - ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةWarnes2006 - ^ أ ب ت ث خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةWood2007 - ^ أ ب ت ث ج خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةCahen-Maurel2019 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةJosephson-Storm2017 - ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةKneller2010 - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةWarnes2009 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةNeubauer1971 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBeiser2003 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةKrell1998 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMiller1974 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةJust1805 - ^ أ ب ت ث ج خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHiebel1954 - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةKleingeld2008 - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةLittlejohns2007 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةvonHardenberg1802 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMonroe1983 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةWernaer1910 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةWessell1975 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةWilloughby1934 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةToy1918 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRehder1948 - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMaeterlinck1912 - ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBeiser2002 - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةCrowe2008 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةO'Meara2014 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةDieckmann1955 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةNovalis1799 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةWeltman1936 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةFreeman2000 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةGwee2011 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةSmith2011 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHahn2004 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMahoney1992 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةCrocker1873 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةTanehisa2009 - ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةStoljar1997 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةSchlegel1798 - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةGelley1991a - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRosellini2000 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMataladeMazza2009 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةSchaber1974 - ^ أ ب Chisholm 1911.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةO'Brien1995 - ^ Novalis, 1772-1801. (2007). Notes for a romantic encyclopaedia : Das Allgemeine Brouillon. Wood, David W., 1968-. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-4294-7128-2. OCLC 137659435.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Gjesdal, Kristin (2014), Zalta, Edward N., ed., Georg Friedrich Philipp von Hardenberg [Novalis] (Fall 2014 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2014/entries/novalis/, retrieved on 2020-09-15

- ^ Lukacs, György (1947). "Romanticism (Die Romantik als Wendung in der deutschen Literatur)". Fortschritt und Reaktion in der deutschen Literatur. Translated by P., Anton. Berlin: Aufbau-Verlag.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةScott1998 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHutcheon&Hutcheon1999 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةLaman2004 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةSteiner1908 - ^ Wallace Fowlie, "Surrealism in 1960: A Backward Glance", Poetry, Vol. 95, No. 6 (Mar., 1960), p. 371.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHeidegger1929 - ^ Achieving more together Novalis-Trust.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMileck1983 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةZiolkowski1961 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةAdamopoulos2015 - ^ Kitchen, Will. (2023) Film, Negation and Freedom: Capitalism and Romantic Critique. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 47-76

وصلات خارجية

- Novalis by Kristin Gjesdal (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- Hymnen an die Nacht – German original in parallel with George MacDonald's translation.

- Novalis: Hymns to The Night – a translation of the work by George MacDonald

- Novalis Online – including a few (computer-generated) hybrid-English translations, and essays on and by Novalis.

- Oberwiederstedt Manor, birthplace of Novalis and home to the International Novalis Society and the Novalis Foundation (in German)

- Aquarium: Friedrich von Hardenberg im Internet – a highly useful multi-lingual web-site for information on Novalis. It provides updates and news in English, German, French, Spanish and Italian, on the latest Novalis translations and reviews, along with general discussions, odd trivia and scholarly articles.

- A detailed review article on Novalis's importance to German culture, philosophy and science by Jeremy Adler – from The Times Literary Supplement, April 16, 2008.

- Es Färbte Sich die Wiese Grün (in English translation) by Leon W. Malinofsky

"Novalis". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Novalis". New International Encyclopedia. 1905. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

مؤلفات ثانوية

- Behler, Ernst. German Romantic Literary Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Beiser, Frederick. German Idealism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Berman, Antoine. L'épreuve de l'étranger. Culture et traduction dans l'Allemagne romantique: Herder, Goethe, Schlegel, Novalis, Humboldt, Schleiermacher, Hölderlin., Paris, Gallimard, Essais, 1984. ISBN 978-2-07-070076-9

- The Cambridge Companion to German Idealism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Fitzgerald, Penelope. The Blue Flower. Mariner Books, 1997. A novelization of Novalis' early life.

- Haywood, Bruce. Novalis, the veil of imagery; a study of the poetic works of Friedrich von Hardenberg, 1772-1801 's-Gravenhage, Mouton, 1959; Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1959.

- Krell, David Farrell. Contagion. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998.

- Kuzniar, Alice. Delayed Endings. Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1987

- Lacoue-Labarthe, Phillipe and Jean-Luc Nancy. The Literary Absolute. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1988.

- Molnár, Geza von. Novalis' "Fichte Studies"

- O’Brien, William Arctander. Novalis: Signs of Revolution. Durham: Duke University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-8223-1519-X

- Pfefferkorn, Kristin. Novalis: A Romantic's Theory of Language and Poetry. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

- Valin, Gerard. Novalis et Henri Bosco, deux poetes mystiques, Thèse de doctorat de lettres, Paris Nanterre, 1972

- CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- صفحات تستخدم جدول كاتب بمتغيرات غير معروفة

- CS1 maint: others

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- CS1 maint: location

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- مواليد 1772

- وفيات 1801

- أشخاص من ارنشتاين، ولاية ساكسونيا أنهالت.

- لوثريون ألمان

- شعراء ألمان

- ملكيون ألمان

- رومانسية

- فلاسفة

- خريجو جامعة لايبزيگ

- أشخاص من ناخبية ساكسونيا

- عائلة هاردنبرگ

- ألمان في القرن 18

- ألمان في القرن 19