گاليسيا (شرق أوروپا) Galicia (Eastern Europe)

گاليسيا

Galicia | |

|---|---|

منطقة تاريخية | |

View of the historical center of Lviv | |

Galicia (dark green) juxtaposed with modern-day Poland and Ukraine (light green) | |

| البلد | |

| أكبر المدن | كراكوف لڤيڤ |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 78٬497 كم² (30٬308 ميل²) |

| صفة المواطن | Galician |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| UTC+1 (CET) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

گاليسيا/جاليسيا (أوكرانية: Галичина (Halychyna)، پولندية: Galicja، ألمانية: Galizien؛ روسية: Галиция (Galitsiya)؛ باليديشية: גאליציע (Galitsie), تشيكية: Halič؛ إنگليزية: Galicia) هي منطقة تقع في المنحدر الشمالي لجبال كارباثيان في جنوب شرقي بولندا، وفي الجزء الغربي من أوكرانيا. تمتد هذه المنطقة من وادي نهر فيستولا، في بولندا إلى وادي نهر دنستر في أوكرانيا، وتغطى مساحة تقدر بـ 82,900 كم². تشمل المدن الرئيسية في منطقة جاليسيا كراكاو في بولندا، ولفوف في أوكرانيا.

يوجد في جاليسيا رواسب غنية من النفط، والغاز الطبيعي. أما المعادن الأخرى الموجودة بها فتشمل الفحم الحجري والحديد والرصاص والملح والكبريت والزنك. يربي المزارعون المواشي ويزرعون المحاصيل كالشعير والبطاطس والشوفان وبنجر السكر والجاودار والقمح. كما أن غابات جاليسيا تُعدُّ مصدرًا لإنتاج خشب الصناعة الخام.

The name of the region derives from the medieval city of Halych,[1][2][3] and was first mentioned in Hungarian historical chronicles in the year 1206 as Galiciæ.[4][5] The eastern part of the region was controlled by the medieval Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia before it was annexed by the Kingdom of Poland in 1352 and became part of the Ruthenian Voivodeship. During the partitions of Poland, it was incorporated into a crown land of the Austrian Empire – the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria.

The nucleus of historic Galicia lies within the modern regions of western Ukraine: the Lviv, Ternopil, and Ivano-Frankivsk oblasts near Halych.[6] In the 18th century, territories that later became part of the modern Polish regions of the Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, and Silesian Voivodeship were added to Galicia after the collapse of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Eastern Galicia became contested ground between Poland and Ruthenia in medieval times and was fought over by Austria-Hungary and Russia during World War I and also Poland and Ukraine in the 20th century. In the 10th century, several cities were founded there, such as Volodymyr and Jaroslaw, whose names mark their connections with the Grand Princes of Kiev. There is considerable overlap between Galicia and Podolia (to the east) as well as between Galicia and south-west Ruthenia, especially in a cross-border region (centred on Carpathian Ruthenia) inhabited by various nationalities and religious groups.

أصول وتنويعات الاسم

The name of the region in the local languages is:

- أوكرانية: Галичина؛ تـُرَوْمَن: Halychyna;

- پولندية: Galicja

- روسين: Галичина, romanized: Halyčyna؛

- روسية: Галиция, romanized: Galitsiya؛

- التشيكية و سلوڤاكية: Halič؛

- ألمانية: Galizien؛

- مجرية: Galícia/Gácsország/Halics؛

- رومانية: Galiția/Halicia؛

- باليديشية: גאַליציע.

Some historians[أ] speculated that the name had to do with a group of people of Thracian origin (i.e. Getae)[7] who during the Iron Age moved into the area after the Roman conquest of Dacia in 106 CE and may have formed the Lypytsia culture with the Venedi people who moved into the region at the end of La Tène period.[7] The Lypytsia culture supposedly replaced the existing Thracian Hallstatt (see Thraco-Cimmerian) and Vysotske cultures.[7] A connection with Celtic peoples supposedly explains the relation of the name "Galicia" to many similar place names found across Europe and Asia Minor, such as ancient Gallia or Gaul (modern France, Belgium, and northern Italy), Galatia (in Asia Minor), the Iberian Peninsula's Galicia, and Romanian Galați.[7][المصدر لا يؤكد ذلك] Some other scholars[من؟] assert that the name Halych has Slavic origins – from halytsa, meaning "a naked (unwooded) hill", or from halka which means "jackdaw".[8] (The jackdaw featured as a charge in the city's coat of arms[9] and later also in the coat of arms of Galicia-Lodomeria.[10] The name, however, predates the coat of arms, which may represent canting or simply folk etymology). Although Ruthenians drove out the Hungarians from Halych-Volhynia by 1221, Hungarian kings continued to add Galicia et Lodomeria to their official titles.

In 1349, in the course of the Galicia–Volhynia Wars, King Casimir III the Great of Poland conquered the major part of Galicia and put an end to the independence of this territory. Upon the conquest Casimir adopted the following title:

Casimir by the grace of God king of Poland and Rus (Ruthenia), lord and heir of the land of Kraków, Sandomierz, Sieradz, Łęczyca, Kuyavia, Pomerania (Pomerelia). لاتينية: Kazimirus, Dei gratia rex Polonie et Rusie, nec non-Cracovie, Sandomirie, Siradie, Lancicie, Cuiavie, et Pomeranieque Terrarum et Ducatuum Dominus et Heres.

Under the Jagiellonian dynasty (Kings of Poland from 1386 to 1572), the Kingdom of Poland revived and reconstituted its territories. In place of historic Galicia there appeared the Ruthenian Voivodeship.

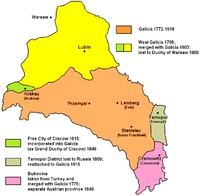

In 1526, after the death of Louis II of Hungary, the Habsburgs inherited the Hungarian claims to the titles of the Kingship of Galicia and Lodomeria, together with the Hungarian crown. In 1772 the Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa, Archduchess of Austria and Queen of Hungary, used those historical claims to justify her participation in the First Partition of Poland. In fact, the territories acquired by Austria did not correspond exactly to those of former Halych-Volhynia – the Russian Empire took control of Volhynia to the north-east, including the city of Volodymyr-Volynskyi (Włodzimierz Wołyński) – after which Lodomeria was named. On the other hand, much of Lesser Poland – Nowy Sącz and Przemyśl (1772–1918), Zamość (1772–1809), Lublin (1795–1809), and Kraków (1846–1918) – became part of Austrian Galicia. Moreover, despite the fact that Austria's claim derived from the historical Hungarian crown, "Galicia and Lodomeria" were not officially assigned to Hungary, and after the Ausgleich of 1867, the territory found itself in Cisleithania, or the Austrian-administered part of Austria-Hungary.

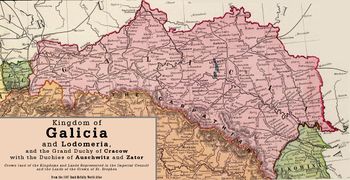

The full official name of the new Austrian territory was the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria with the Duchies of Auschwitz and Zator. After the incorporation of the Free City of Kraków in 1846, it was extended to Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, and the Grand Duchy of Kraków with the Duchies of Auschwitz and Zator (ألمانية: Königreich Galizien und Lodomerien mit dem Großherzogtum Krakau und den Herzogtümern Auschwitz und Zator).

Each of those entities was formally separate; they were listed as such in the Austrian emperor's titles, each had its distinct coat-of-arms and flag. For administrative purposes, however, they formed a single province. The duchies of Auschwitz (Oświęcim) and Zator were small historical principalities west of Kraków, on the border with Prussian Silesia. Lodomeria, under the name Volhynia, remained under the rule of the Russian Empire – see Volhynian Governorate.

تاريخ

روذينيا الحمراء

كانت جاليسيا مملكة مستقلة خلال العصور الوسطى. وأصبحت جزءاً من بولندا خلال القرن الرابع عشر الميلادي واحتلتها النمسا في أواخر القرن الثامن عشر. وحصلت عام 1867م على حكم ذاتي محدود تحت الحكم النمساوي. ازدهرت المنطقة بمركزها الثقافي والتعليمي للغة البولندية. ثم أصبحت مصدراً لحركة الاستقلال البولندية. أصبحت جاليسيا جزءاً من الدولة البولندية المستقلة التي تم تأسيسها بعد الحرب العالمية الأولى (1914- 1918م). وفي نهاية الحرب العالمية الثانية، عام 1945م، ضمت جاليسيا الشرقية إلى أوكرانيا السوفييتية بمقتضى اتفاقية بين الاتحاد السوفييتي (سابقًا) وبولندا. وفي عام 1991، نالت أوكرانيا استقلالها وظلت جاليسيا الغربية جزءاً من بولندا.

أمراء گاليسيا

- Géza II of Hungary (1150-1162)

- Roman the Great, prince of Halych-Volhynia (1199–1205) united Galicia and Volhynia into mighty principality

- Daniel of Halych, prince of Halych-Volhynia (1211—1212, 1229—1235, 1238—1253), king of Halych-Volhynia (1253-1264)

- Leo I of Halych, prince of Halych-Volhynia (1293-1301), moved the capital from Halych to Lviv (Leopolis, Lemberg, Lwów, Lvov, Liov).

- Andrew of Halych and Leo II of Halych, the last Ruthenian princes of Halych-Volhynia (died 1323)

- Boleslaw Iurii II of Halych, Mazovian-Ruthenian prince of Halych-Volhynia (1323-1340) ruled with Maria, Andrew's and Leo's II sister.

- Lubart, Lithuanian prince of Halych (1343-1349) and prince of Volhynia (1366-1370)

- Władysław Opolczyk, Silesian prince, Hungarian count palatine, governor of Halych (1372-1378) [11]

بعد وفاة جورج الثاني من هاليخ، تم ضم گاليسيا إلى مملكة پولندا، بين 1340 و 1366، أأثناء حكم كاسيمير الثالث من پولندا.

ملوك گاليسيا

- Andrew II of Hungary the first king of Galicia and Lodomeria, lat. Rex Galiciae at Lodomerie (1206-1235)

- Coloman of Hungary, King of Lodomeria (1215-1219 and 1220-1221) and his wife Salomea of Poland, Reges Galiciae et Lodomeriae

- Protectorate by White Horde of Khans (1253-1338)

- Daniel of Halych, the first Ruthenian king of Halych-Volhynia (1253-1264), crowned by a papal legat, archbishop Opizo in Dorohychyn in 1253

- George I of Halych, king of Halych-Volhynia (1301–1308)

- Polish kings 1349-1772

- Maria Theresa of Austria Holy Roman Empress 1772-1780

- Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor 1780-1790

- Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor 1790-1792

- Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor 1792-1835

- Ferdinand I of Austria 1835-1848

- Franz Joseph I of Austria 1848-1916

- Charles I of Austria 1916-1918

من تقسيم پولندا حتى مؤتمر ڤيينا

من 1815 حتى 1860

الاستقلال الذاتي الگاليسي

الشعب

In 1773, Galicia had about 2.6 million inhabitants in 280 cities and market towns and approximately 5,500 villages. There were nearly 19,000 noble families, with 95,000 members (about 3% of the population). The serfs accounted for 1.86 million, more than 70% of the population. A small number were full-time farmers, but by far the overwhelming number (84%) had only smallholdings or no possessions.[citation needed]

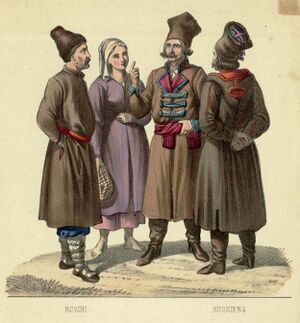

Galicia had arguably the most ethnically diverse population of all the countries in the Austrian monarchy, consisting mainly of Poles and "Ruthenians";[12] the peoples known later as Ukrainians and Rusyns, as well as ethnic Jews, Germans, Armenians, Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians, Roma and others. In Galicia as a whole, the population in 1910 was estimated to be 45.4% Polish, 42.9% Ruthenian, 10.9% Jewish, and 0.8% German.[13] This population was not evenly distributed. The Poles lived mainly in the west, with the Ruthenians predominant in the eastern region ("Ruthenia"). At the turn of the twentieth century, Poles constituted 88% of the whole population of Western Galicia and Jews 7.5%. The respective data for Eastern Galicia show the following numbers: Ruthenians 64.5%, Poles 22.0%, Jews 12%.[14][15] Of the 44 administrative divisions of Austrian eastern Galicia, Lviv (پولندية: Lwów, ألمانية: Lemberg) was the only one in which Poles made up a majority of the population.[16] Anthropologist Marianna Dushar has argued that this diversity led to a development of a distinctive food culture in the region.[17]

The Polish language was the most spoken language in Galicia as a whole, although the eastern part of the region was predominantly Ruthenian-speaking. According to the 1910 census, 58.6% of Galicia spoke Polish as its mother tongue, compared to 40.2% who spoke a Ruthenian language.[18] The number of Polish-speakers may have been inflated because Jews were not given the option of listing Yiddish as their language.[19] Eastern Galicia was the most diverse part of the region, and one of the most diverse areas in Europe at the time.

The Galician Jews immigrated in the Middle Ages from Germany. German-speaking people were more commonly referred to by the region of Germany where they originated (such as Saxony or Swabia). For those who spoke different native languages, e.g. Poles and Ruthenians, identification was less problematic, and the widespread multilingualism blurred ethnic divisions.

Religiously, Galicia is predominantly Catholic, and Catholicism is practiced in two rites. Poles are Roman Catholic, while Ukrainians belong to the Greek Catholic Church. Other Christians belong to one of the Ukrainian Orthodox Churches. Until the Holocaust, Judaism was widespread, and Galicia was the center of Hasidism.

المدن والبلدات الكبرى

View of the historic البلدة القديمة في لڤيڤ |

منظر البلدة القديمة في سانوك |

انظر أيضاً

- Halych-Volhynia

- List of rulers of Halych and Volhynia

- List of Galician rulers

- List of Ukrainian rulers

- Lesser Poland

- Bukovina

- Subdivisions of Galicia

- Galician Soviet Socialist Republic

- Personalities from Galicia (modern period)

- Ruthenians

- Galician Jews

- Counts of Galicia and Poland

المراجع

- ^ "European Kingdoms – Eastern Europe – Galicia". The History Files. Kessler Associates. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ^ Zakharii, Roman. "History of Galicia". Toronto Ukrainian Genealogy Group. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ "Historical Glossary: Galicia (Halychyna)". Ukrainians in the United Kingdom. 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ "Rex+Galiciae+et+Lodomeriae"&pg=PA165 Die Oesterreichisch-ungarische Monarchie in Wort und Bild, Volume 19 (in الألمانية). Austria: K.k. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei. 1898. p. 165. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

Um welchen Preis er dies that, wird nicht überliefert, aber seit dieser Zeit, das ist seit dem Jahre 1206 findet sich in seinen Urkunden der Titel: 'Rex Galiciae et Lodomeriae'

- ^ Martin Dimnik (12 June 2003). The Dynasty of Chernigov, 1146–1246. Cambridge University Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-1-139-43684-7. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew (2006). Ukraine's Orange Revolution. Andrew Wilson (historian): Yale University Press. p. 34. ISBN 0-300-11290-4.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Galicia and Lodomeria at the Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- ^ Max Vasmer points to Russian galitsa, an adjectival form meaning "jackdaw" – see Galich in Russisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch (1950–1958).

- ^ Halych coat of arms: 14th century

- ^ Coat of arms of Galicia-Lodomeria

- ^ "Władysław Opolczyk – Wikipedia, wolna encyklopedia" (in (Polish)). Pl.wikipedia.org. 2009-07-15. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Magocsi, Paul R. (2002). The Roots of Ukrainian Nationalism: Galicia as Ukraine's Piedmont. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 57.

- ^ Paul Robert Magocsi. (1996). A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University ofToronto Press. Pg. 424.

- ^ Piotr Eberhardt. Ethnic groups and population changes in twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe: history, data, analysis. M.E. Sharpe, 2003. pp.92–93. ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5

- ^ Timothy Snyder. (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 123

- ^ Timothy Snyder. (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 134

- ^ Plakhta, Dmytro (22 August 2018). ""Food is a little universal anchor and a way of identification"".

- ^ Anstalt G. Freytag & Berndt (1911). Geographischer Atlas zur Vaterlandskunde an der österreichischen Mittelschulen. Vienna: K. u. k. Hof-Kartographische. "Census December 31st 1910"

- ^ Timothy Snyder. (2003).The Reconstruction of Nations. New Haven: Yale University Press, pg. 134

- الهامش

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Galicia: A Historical Survey and Bibliographic Guide (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1983). Concentrates on the historical, or Eastern Galicia.

- Andrei S. Markovits and Frank E. Sysyn, eds., Nationbuilding and the Politics of Nationalism: Essays on Austrian Galicia (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1982). Contains an important article by Piotr Wandycz on the Poles, and an equally important article by Ivan L. Rudnytsky on the Ukrainians.

- Christopher Hann and Paul Robert Magocsi, eds., Galicia: A Multicultured Land (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005). A collection of articles by John Paul Himka, Yaroslav Hrytsak, Stanislaw Stepien, and others.

- A.J.P. Taylor, The Habsburg Monarchy 1809–1918, 1941, discusses Habsburg policy toward ethnic minorities.

- (Polish) Grzegorz Hryciuk, Liczba i skład etniczny ludności tzw. Galicji Wschodniej w latach 1931-1959, [Number and Ethnic Composition of the People of so-called Eastern Galicia 1931-1959] Lublin 1996

- Alison Fleig Frank, Oil Empire: Visions of Prosperity in Austrian Galicia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005). A new monograph on the history of the Galician oil industry in both the Austrian and European contexts.

- Dohrn, Verena, journey to Galicia, publishing house S. Fischer, 1991, ISBN 3-10-015310-3

وصلات خارجية

- Galizien

- Gesher Galicia ("Bridge to Galicia")

- Halychyna! Galicia! Gacsorszag! Galizien! Galicja!

- Jewish Encyclopedia

- Galician Research

- Coat of arms of Galicia

- Flag of Galicia

- Galicia in UkrStor.com (the web library of historical documents & publicism about Malorussia/Ukraine)

- Volhynia-Galicia (Polish)

- Ukraine: Nation, Culture (about Galician region)

- [1] Spezialkarte von des Koenigreichs Galizien und Lodomerien westlichen Kreisen. Nro. 35. Wien, Josef von Reilly. 1791

- [2] Das Koenigreichs Galizien und Lodomerien mittlere Kreise. Nro. 36. Wien, Josef von Reilly. 1791

- [3] Galizien nach den neuesten Beobabachtungen. Wien, Tranquillo Mollo, 1817

- [4] Charte von Ost und West Galizien nach den neuesten astronomischen Ortsbestimmungen entworfen, und revidirt auf der Sternwarte Seeberg bey Gotha gezeichnet von G. R. Schmidburg. - Weimar im Verlage des Geograph. Instituts - Berichtigt nach dem Wiener Frieden vom 14t October. 1809. Weimar, Geographisches Institut 1809

قالب:Galicia and Lodomeria timeline

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages using infobox settlement with no coordinates

- Articles containing أوكرانية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing پولندية-language text

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- Articles containing يديشية-language text

- Articles containing تشيكية-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Articles containing روسين-language text

- Articles containing سلوڤاكية-language text

- Articles containing مجرية-language text

- Articles containing رومانية-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة from February 2013

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2014

- Lang and lang-xx template errors

- گاليسيا (شرق اوروپا)

- مناطق تاريخية بولندية

- Ruthenia

- مناطق تاريخية أوكرانية

- جاليات يهودية تاريخية

- مناطق اوروپا

- Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia

- Historical regions in Poland

- Historical regions in Ukraine

- Historical regions in the Kingdom of Hungary

- Carpathians

- Lesser Poland

- Place name etymologies

- Rusyn communities