إستر (ملكة)

| إستر، شخصية توراتية | |

|---|---|

| ملكة توراتية على بلاد فارس | |

الملكة إستر (1879) بريشة إدوين لونگ | |

| سبقه | وشتي |

| وُلِد | هداسة الامبراطورية الأخمينية |

| الزوج | أخشورش |

| الأب | أبيحيل (الأصلي)، مردخاي (بالتبني) |

| الديانة | اليهودية |

إستر[أ] توصف في سفر أستير بأنها ملكة يهودية زوجة الملك الفارسي أخشورش (الذي يُتعارف أنه خشايارشا الأول، حكمت 486–465 ق.م.).[1] في السرد التوراتي، أراد أخشورش زوجة جديدة بعد أن أصبحت ملكته، وشتي، تعصى أوامره، فاختار إستر لجمالها. وزير الملك، هامان، أساء له ابن عم إستر وحارسها، مردخاي، فيحصل على إذن من الملك بقتل جميع اليهود. إستر تُحبط الخطة، وتحصل على إذن من الملك بقتل كل أعدائهم، ويفعلون ذلك.

قصة إستر هي الأساس التقليدي لعيد پوريم، الذي يُحتفل به في التاريخ الممنوح في القصة الذي كان يُفترض فيه أن يسري أمر هامان، وهو نفس اليوم الذي قتل فيه اليهود أعداءهم بعد إحباط خطة هامان.

أصل الاسم

إستر قد تكون مشتقة من اسم الإلهة عشتار. يقدم سفر دانيال قصص عن اليهود في المنفى الذين يحملون أسماء متعلقة بالآلهة البابلية، ويُفهم أن "مردخاي" هو خادم لآلهة البابلية "مردوخ". قد يكون التفسير العبري لاسم "إستر" مختلف عن الأصول السامية للاسم "النجم/نجم الصباح/المساء"،[2] الأمر الذي يعتمد على نُطق حرف /th/ بالأوغاريتية Athtiratu[3] وبالعربية عشتار.[4] ومن ثم ينبغي أن يكون الاشتقاق ثانوياً لحرف العين حتى يتم الخلط بينه وبين الألف (يمثلهما حروف العلة في الأكادية)، والحرف الثاني الساكن a / s / (كما في الكلمة الآرامي asthr وتعني "النجم الساطع") بدلاً من a / sh / كما في العبرية والأكثر شيوعًا في الأكادية.

يربط الترجوم[5] الاسم بالكلمة الفارسية، setareh وتعني "النجمة" (باللغة الفارسية: ستاره)، موضحاً أن إستر سميت بهذا الاسم لكونها جميلة مثل نجمة الصباح. في التلمود (Tractate Yoma 29a)، تقارن إستر "بنجمة الصباح"، وهي موضوعاً رئيسياً لسفر المزامير 22، حيث يبدأ بأغنية نجمة الصباح.

يخن أ. س. يهودا أن اسم إستر مشتق من الكلمة الميدية astra وتعني |نبات الآس.[6][7] يتماشى هذا مع نظيرتها العبرية المدونة في الكتاب المقدس، Hadassah، والتي تعني أيضاً "نبات الآس".

في التوراة

في السرد التوراتي، فقد كان الملك أخشورش سكراناً في عيد وأمر ملكته، وشتي، أن تمـْثـُل أمامه وأمام ضيوفه عارية من كل ملابسها إلا تاجها،[8] لتعرض جمالها. فحين رفضت المثول، تخلص منها وبحث عن زوجة ملكة جديدة عبر ما يشبه مسابقة ملكة جمال. فإختار إستر، الابنة اليتيمة لـ "أبيحيل" من سبط بنيامين وكانت تعيش في كنف ابن عمها مردخاي، وكانا من مجتمع السبي اليهودي في فارس.

لاحقاً، رفض مردخاي أن ينحني لهامان من يأگوگ، الذي كان قد عـُيـِّن قبل قليل كبيراً لمستشاري أخشورش. وكان هامان قد حصل على موافقة الملك لطلبه قتل كل اليهود في فارس. فحين علمت إستر بذلك، طلب مردخاي منها أن تكشف للملك أنها يهودية وأن تطلب من إلغاء أمره. ترددت إستر، قائلةً أنها قد تـُقتـَل لو ذهبت للملك بدون استدعاء إذا ما اتضح أن الملك لا يريد رؤيتها؛ إلا أن مردخاي ألح عليها. فذهبت إلى الملك، الذي رحب بها وقال أنه سيعطيها أي شيء تطلبه. فبدلاً من أن تطلب مباشرةً ما تريد، فقد دعت الملك وهامان إلى مأدبة في اليوم التالي. وأثناء المأدبة، سأل الملك إستر، مرة أخرى، إذا ما كان هناك شيء تريد. وهذه المرة، طلبت من الملك أن ينقذ حياتها وحياة كل اليهود. فسأل الملك عمن يهددهم، فقالت إنه هامان. فألقى هامان بنفسه على قدميها؛ فظن الملك أن هامان يهجم عليها، فيأمر بقتله، ويمنح كل أملاك هامان لإستر. فأخبرت إستر الملك عن دور مردخاي في حياتها، فيعيِّنه الملك كبيراً لمستشاريه. ثم تطلب إستر من الملك أن يلغي أمره السابق بقتل اليهود، فيسمح لإستر ومردخاي أن يلغياه كيفما شاءا. فأرسلا أمراً بإسم الملك أن اليهود بإمكانهم التجمع والدفاع عن أنفسهم، وأن بإمكانهم قتل أي شخص يهددهم، هم أو عائلاتهم، وأن يسلبوه أملاكه. وفي الثالث عشر من آذار، نفس اليوم الذي كان هامان قد حدد لقتل اليهود، قام اليهود بقتل 500 شخص من أعدائهم، إلا أنهم لم ينهبوا، وفي اليوم التالي قتلوا نحو 75,000 شخصاً، أيضاً بدون نهب، ثم أقاموا عيداً.[9]

In the third year of the reign of King Ahasuerus of Persia the king banishes his queen, Vashti, and seeks a new queen. Beautiful maidens gather together at the harem in the citadel of Susa under the authority of the eunuch Hegai.[10]

Esther, a cousin of Mordecai, was a member of the Jewish community in the Exilic Period who claimed as an ancestor Kish, a Benjamite who had been taken from Jerusalem into captivity. She was the orphaned daughter of Mordecai's uncle, Abihail, from the tribe of Gad. Upon the king's orders, Esther is taken to the palace where Hegai prepares her to meet the king. Even as she advances to the highest position of the harem, perfumed with gold and myrrh and allocated certain foods and servants, she is under strict instructions from Mordecai, who meets with her each day, to conceal her Jewish origins. The king falls in love with her and makes her his Queen.[10]

Following Esther's coronation, Mordecai learns of an assassination plot by Bigthan and Teresh to kill King Ahasuerus. Mordecai tells Esther, who tells the king in the name of Mordecai, and he is saved. This act of great service to the king is recorded in the Annals of the Kingdom.

After Mordecai saves the king's life, Haman the Agagite is made Ahasuerus' highest adviser, and orders that everyone bow down to him. When Mordecai (who had stationed himself in the street to advise Esther) refuses to bow to him, Haman pays King Ahasuerus 10,000 silver talents for the right to exterminate all of the Jews in Ahasuerus' kingdom. Haman casts lots, Purim, using supernatural means, and sees that the thirteenth day of the Month of Adar is a fortunate day for the genocide. Using the seal of the king, in the name of the king, Haman sends an order to the provinces of the kingdom to allow the extermination of the Jews on the thirteenth of Adar. When Mordecai learns of this, he tells Esther to reveal to the king that she is Jewish and ask that he repeal the order. Esther hesitates, saying that she could be put to death if she goes to the king without being summoned; nevertheless, Mordecai urges her to try. Esther asks that the entire Jewish community fast and pray for three days before she goes to see the king; Mordecai agrees.

On the third day, Esther goes to the courtyard in front of the king's palace, and she is welcomed by the king, who stretches out his scepter for her to touch, and offers her anything she wants "up to half of the kingdom". Esther invites the king and Haman to a banquet she has prepared for the next day. She tells the king she will reveal her request at the banquet. During the banquet, the king repeats his offer again, whereupon Esther invites both the king and Haman to a banquet she is making on the following day as well.

Seeing that he is in favor with the king and queen, Haman takes counsel from his wife and friends to build a gallows upon which to hang Mordecai; as he is in their good favors, he believes he will be granted his wish to hang Mordecai the very next day. After building the gallows, Haman goes to the palace in the middle of the night to wait for the earliest moment he can see the king.

That evening, the king, unable to sleep, asks that the Annals of the Kingdom be read to him so that he will become drowsy. The book miraculously opens to the page telling of Mordecai's great service, and the king asks if he had already received a reward. When his attendants answer in the negative, Ahasuerus is suddenly distracted and demands to know who is standing in the palace courtyard in the middle of the night. The attendants answer that it is Haman. Ahasuerus invites Haman into his room. Haman, instead of requesting that Mordecai be hanged, is ordered to take Mordecai through the streets of the capital on the Royal Horse wearing the royal robes. Haman is also instructed to yell, "This is what shall be done to the man whom the king wishes to honor!"

After spending the entire day honoring Mordecai, Haman rushes to Esther's second banquet, where Ahasuerus is already waiting. Ahasuerus repeats his offer to Esther of anything "up to half of the kingdom". Esther tells Ahasuerus that while she appreciates the offer, she must put before him a more basic issue: she explains that there is a person plotting to kill her and her entire people, and that this person's intentions are to harm the king and the kingdom. When Ahasuerus asks who this person is, Esther points to Haman and names him. Upon hearing this, an enraged Ahasuerus goes out to the garden to calm down and consider the situation.

While Ahasuerus is in the garden, Haman throws himself at Esther's feet asking for mercy. Upon returning from the garden, the king is further enraged. As it was the custom to eat on reclining couches, it appears to the king as if Haman is attacking Esther. He orders Haman to be removed from his sight. While Haman is being led out, Harvona, a civil servant, tells the king that Haman had built a gallows for Mordecai, "who had saved the king's life". In response, the king says "Hang him (Haman) on it".

After Haman is put to death, Ahasuerus gives Haman's estate to Esther. Esther tells the king about Mordecai being her relative, and the king makes Mordecai his adviser. When Esther asks the king to revoke the order exterminating the Jews, the king is initially hesitant, saying that an order issued by the king cannot be repealed. Ahasuerus allows Esther and Mordecai to write another order, with the seal of the king and in the name of the king, to allow the Jewish people to defend themselves and fight with their oppressors on the thirteenth day of Adar.

On the thirteenth day of Adar, the same day that Haman had set for them to be killed, the Jews defend themselves in all parts of the kingdom and rest on the fourteenth day of Adar. The fourteenth day of Adar is celebrated with the giving of charity, exchanging foodstuffs, and feasting. In Susa, the Jews of the capital were given another day to kill their oppressors; they rested and celebrated on the fifteenth day of Adar, again giving charity, exchanging foodstuffs, and feasting as well.[11]

The Jews established an annual feast, the feast of Purim, in memory of their deliverance. Haman having set the date of the thirteenth of Adar to commence his campaign against the Jews, this determined the date of the festival of Purim.[12]

پوريم

أسس اليهود عيداً سنوياً، عيد پوريم، احتفالاً بذكرى خلاصهم. حدد هامان تاريخ 13 أذار لبدء حملته ضد اليهود. التاريخ الذي تحدد على أساسه عيد پوريم.[12]

تفسيرات

يزعم ديان تيدبال بأنه في حين أن تعتبر وشتي "أيقونة أنثوية" ، فإن إستر تعتبر أيقونة ما بعد الأنثوية.[13]

ويشير أبراهام كيوپر إلى بعض "الجوانب الغير مرغوب فيها" في شخصيتها: أنها لم تكن يجب أن توافق على أن تحل محل وشتي، وأنها امتنعت عن إنقاذ بلدها حتى تعرضت حياتها للخطر، وأنها تنفذ الانتقام المتعطش للدماء.[14]

تبدأ الحكاية مع إستر باعتبارها جميلة ومطيعة، ولكنها في الوقت نفسه شخصية سلبية نسبياً. خلال القصة، تتطور إستر إلى شخص يلعب دوراً حاسماً في مستقبلها ومستقبل شعبها.[15] وفقاً لسيدني وايت كروفورد، "إن موقع إستر في بلاط ذكوري يعكس وضع اليهود في العالم الغير يهودي، في ظل الخطر الكامن تحت السطح الذي يبدو هادئاً".[16] ترتبط إستر دانيال حيث يمثل كلاهما "نوعية" اليهود الذين يعيشون في الشتات، ويأملون في أن يعيشوا حياة ناجحة في بيئة غريبة.

إستر كنموذج للفصاحة

تبعاً لسوزان زايسك، ففي الحقيقة لم تستخدم إستر سوى الخطابة لإقناع الملك بإنقاذ شعبها، فإن قصة إستير هي "خطاب المنفى والتمكين الذي شكل، منذ آلاف السنين، خطاب الشعوب المهمشة مثل اليهود والنساء، والأميركيان الأفارقة"، لإقناع أولئك الذين لديهم السلطة عليهم.[17]

الثقافة الفارسية

نظراً للصلة التاريخية العظيمة بين التاريخ الفارسي واليهودي، يُطلق على اليهود الفارسيين المعاصرون اسم "أطفال إستر". يقع المبنى المبجل باعتباره قبر إستر ومردخاي في همدان، إيران،[18] على الرغم من أن قرية كفر برعم في شمال إسرائيل تدعي أيضاً بأنها تضم قبر الملكة إستر.[19]

تصويرات لإستر

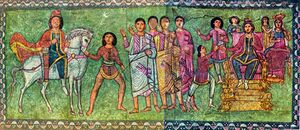

هناك عدة لوحات تصور إستر، منها لوحة لميليه. تعتبر لوحة إستر أمام أخشورش، من اللوحات التي تمثل أهم أجزاء القصة.

تقديسها في المسيحية

تاريخياً، كان وضع إستر كسفر كنسي من أسفار الكتاب المقدس محل خلاف. على سبيل المثال، في القرون الأولى المسيحية، لا يظهر سفر إستر في قوائم الأسفار التي رواها مليتو، وأثاناسيوس، وسيريل، وگريگوريوس النزينزي، وغيرها. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، لا توجد نسخ من سفر إستر ضمن مخطوطات البحر الميت بالقرب من قمران. ومع ذلك، بحلول القرن الرابع الميلادي، قبلت غالبية الكنائس الغربية سفر إستر كجزء من كتبهم المقدسة.[20]

يتم إحياء ذكرى إستر أيضاً as a matriarch في تقويم القديسين سينود الكنيسة اللثورية-ميزوري في 24 مايو. ومعترف بها أيضاً كقديسة في الكنائس الأرثوذكسية الشرقية والكنيسة الأرثوذوكسية القبطية. "تحتوي الطبعة السبعينية لإستر على ستة أجزاء (مجموعها 107 آية) غير موجودة في الكتاب المقدس العبري. على الرغم من أن هذه التفسيرات قد كُتبت في الأصل باللغة العبرية، إلا أنها لم تبق إلا في النصوص اليونانية. لأن إصدار الكتاب المقدس العبري لقصة إستر لا يحتوي على صلوات ولا حتى إشارة واحدة إلى الرب، يبدو أن الكتبة اليونانيون شعروا أنهم مضطرون لإعطاء الحكاية توجهاً دينياً أكثر وضوحاً، في إشارة إلى "الله" أو "الرب" خمسين مرة.[21] أضيفت هذه الإضافات إلى استير في أپوكريفا في القرن الثاني أو الأول قبل الميلاد تقريباً.[22][23]

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

الهامش

- ^ Littman, Robert J. (January 1975). "The Religious Policy of Xerxes and the Book of Esther". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 65 (3): 145–155. doi:10.2307/1454354. JSTOR 1454354.

- ^ Huehnergard, John (2008-04-10). "Appendix 1: Afro-Asiatic". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 225–46. ISBN 978-1-13946934-0.

- ^ Rahmouni, Aïcha; Ford, J.N. (2008). "Section 1, The Near and Middle East". Divine Epithets in the Ugaritic Alphabetic Texts. Brill. p. 86. ISBN 978-900415769-9.

- ^ Offord, Joseph (April 1915). "The Deity of the Crescent Venus in Ancient Western Asia". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland: 198. JSTOR 25189307.

- ^ Targum to Esther 2:7

- ^ Abusch, T. (1999). "Ishtar". In Karel van der Toom, Bob Becking, Pieter W. van der Horst, eds. Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. 2nd extensively rev. ed. Brill. p. 455.

- ^ Barton, John; Muddiman, John (2001-09-06). "Esther". The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19875500-5.

- ^ Rachel Held Evans (2012-09-24). "Esther Actually: Vashti, the Other Queen". rachelheldevans.com.

- ^ Hirsch, Emil G.; Prince, John Dyneley; Schechter, Solomon (1936). "Esther". Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Co.

- ^ أ ب Solle 2006, p. 107.

- ^ Hirsch, Prince & Schechter 1936.

- ^ أ ب Crawford, Sidnie White. "Esther: Bible", Jewish Women's Archive. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "Crawford" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ Tidball, Dianne (2001). Esther, a True First Lady: A Post-Feminist Icon in a Secular World. Christian Focus Publications. ISBN 978-1-85792671-2.

- ^ Kuyper, Abraham (2010-10-05). Women of the Old Testament. Zondervan. pp. 175–76. ISBN 978-0-31086487-5.

- ^ Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann and Perkins, Pheme. The New Oxford Annotated Bible, Oxford University Press, 2007 ISBN 978-0-19528880-3

- ^ Crawford, Sidnie White. "Esther", Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible, James D. G. Dunn, John William Rogerson, eds., Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2003 ISBN 978-0-80283711-0

- ^ Zaeske, Susan (2003). "Unveiling Esther as a Pragmatic Radical Rhetoric". Philosophy and Rhetoric. 33 (3): 194.

- ^ Vahidmanesh, Parvaneh (5 May 2010). "Sad Fate of Iran's Jews". Payvand.

- ^ Schaalje, Jacqueline (June 2001). "Ancient synagogues in Bar'am and Capernaum". Jewish Magazine.

- ^ McDonald, Lee Martin (2006-11-01). The Biblical Canon: Its Origin, Transmission, and Authority. Baker Academic. pp. 56, 109, 128, 131. ISBN 978-0-80104710-7.

- ^ Harris, Stephen; Platzner, Robert, The Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible, p. 375.

- ^ Vanderkam, James; Flint, Peter, The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls, p. 182.

- ^ Esther, EC Marsh, http://www.ecmarsh.com/lxx/Esther/.

المصادر

- Zaeske, Susan. "Unveiling Esther as a Pragmatic Radical Rhetoric", Philosophy and Rhetoric, vol. 33, issue 3.

للاستزادة

- Beal, Timothy K. (1997-12-11). The Book of Hiding: Gender, Ethnicity, Annihilation, and Esther (1st ed.). London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41516780-2. Postmodern theoretical apparatus, e.g., Jacques Derrida, Emmanuel Levinas.

- Fox, Michael V. (2010-04-01). Character and Ideology in the Book of Esther: Second Edition with a New Postscript on a Decade of Esther Scholarship (2nd ed.). Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock. ISBN 978-1-60899495-3.

- Sasson, Jack M. (1990). "Esther". In Alter, Robert; Kermode, Frank (eds.). The Literary Guide to the Bible. Harvard University Press. pp. 335–41. ISBN 978-0-67487531-9.

- Kahr, Madlyn Millner (1968). The Book of Esther in Seventeenth-century Dutch Art. New York University.

- Webberley, Helen (Feb 2008). "Rembrandt and The Purim Story". The Jewish Magazine.

- White, Sidnie Ann (1989-01-01). "Esther: A Feminine Model for Jewish Diaspora". In Day, Peggy Lynne (ed.). Gender and Difference in Ancient Israel. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-45141576-6.

- Grossman, Jonathan (2011). Esther: The Outer Narrative and the Hidden Reading. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506221-1.

وصلات خارجية

- Articles containing عبرية-language text

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing Imperial Aramaic (700-300 BCE)-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- أنبياء التوراة

- إستر

- Women in the Hebrew Bible

- Jewish royalty

- Order of the Eastern Star

- أشخاص مشاهير في التقويم الديني اللوثري

- Christian female saints from the Old Testament

- Persian queens consort

- إيرانيو القرن الخامس ق.م.

- يهود فارسيون