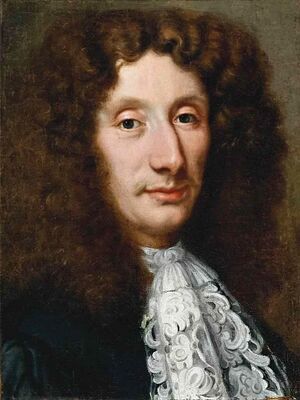

فرانشسكو ردي

فرانشسكو ردي | |

|---|---|

Francesco Redi | |

| |

| وُلِدَ | فبراير 18, 1626 أرتسو، إيطاليا |

| توفي | مارس 1, 1697 (aged 71) پيزا، إيطاليا |

| القومية | توسكانيا |

| المدرسة الأم | جامعة پيزا |

| عـُرِف بـ | علم الأحياء التجريبي علم الطفيليات تجارب تحدت التولد اللحظي spontaneous generation |

| السيرة العلمية | |

| المجالات | الطب، علم الحشرات |

| الهيئات | فلورنسا |

فرانشسكو ردي Francesco Redi (عاش 18 فبراير 1626 - 1 مارس 1697) كان طبيب وعالم طبيعيات وشاعر إيطالي. بيَّن أن وجود دود الجيف maggots في اللحم المتعفن لا ينتج من التولد اللحظي spontaneous generation، بل من بويضات وضعها على اللحم الذباب. اهتمام ردي كان سببه كتاب لوليام هارڤي اقترح فيه أن الحشرات والديدان والضفادع تأتي من بذور أو بويضات أصغر من أن تُرى. وفي 1668، كانت طريقة ردي التجريبية التقليدية هي أحد أول الأمثلة للتجارب الحيوية تحت ضوابط مناسبة. وقد كرر نفس التجربة بطرق مختلفة، مغيراً في كل مرة متغير واحد، ومجرياً الاختبارات المناسبة. فقد أعد ردي ثمان قوارير بأنواع مختلفة من اللحم؛ أربعاً تـُركوا في العراء وأربعاً أحكم عزلهم. فتعفن اللحم في كل القواريرـ إلا أن الدود ظهر فقط في القوارير المفتوحة التي أمكن للذباب الدخول إليها بحرية. (ولاستبعاد احتمال أن دورة حياة دود الجيف قد تأثرت في القوارير المقفلة، فقد واصل الاختبار بسلسلتين من القوارير، متيحاً الهواء، ولكن بدون ذباب، لأن يدخل قوارير الاختبار المقطاة بنوع خاص من المرشحات الدقيقة.)

Having a doctoral degree in both medicine and philosophy from the University of Pisa at the age of 21, he worked in various cities of Italy. A rationalist of his time, he was a critic of verifiable myths, such as spontaneous generation.[1] His most famous experiments are described in his magnum opus Esperienze intorno alla generazione degl'insetti (Experiments on the Generation of Insects), published in 1668. He disproved that vipers drink wine and could break glasses and that their venom was poisonous when ingested. He correctly observed that snake venoms were produced from the fangs, not the gallbladder, as was believed. He was also the first to recognize and correctly describe details of about 180 parasites, including Fasciola hepatica and Ascaris lumbricoides. He also distinguished earthworms from helminths (like tapeworms, flukes, and roundworms). He possibly originated the use of the control, the basis of experimental design in modern biology. A collection of his poems first published in 1685 Bacco in Toscana (Bacchus in Tuscany) is considered among the finest works of 17th-century Italian poetry, and for which the Grand Duke Cosimo III gave him a medal of honour.

أُطلِق اسمه على فوهة على سطح المريخ تكريماً له.

السيرة

The son of Gregorio Redi and Cecilia de Ghinci, Francesco Redi was born in Arezzo on 18 February 1626. His father was a renowned physician at Florence. After schooling with the Jesuits, Francesco Redi attended the University of Pisa from where he obtained his doctoral degrees in medicine and philosophy in 1647, at the age of 21.[2] He constantly moved, to Rome, Naples, Bologna, Padua, and Venice, and finally settled in Florence in 1648. Here he was registered at the Collegio Medico where he served at the Medici Court as both the head physician and superintendent of the ducal apothecary to Ferdinando II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany and his successor, Cosimo III. It is here that most of his academic works were achieved, which earned him membership in Accademia dei Lincei. He was also a member of the Accademia del Cimento (Academy of Experiment) from 1657 to 1667.[3]

He died in his sleep on 1 March 1697 in Pisa and his remains were returned to Arezzo for interment.[4][5]

A collection of his letters is held at the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland.[6]

السيرة العلمية

علم السميات التجريبي

In 1664 Redi wrote his first monumental work Osservazioni intorno alle vipere (Observations on Vipers) to his friend Lorenzo Magalotti, secretary of the Accademia del Cimento. In this he began to break the prevailing scientific myths (which he called "unmasking of the untruths") such as vipers drink wine and shatter glasses, their venom is poisonous if swallowed, the head of the dead viper is an antidote, the viper's venom is produced from the gallbladder, and so on. He explained rather how snake venom is unrelated to the snake’s bite, an idea contrary to popular belief.[7] He performed a series of experiments on the effects of snakebites and demonstrated that venom was poisonous only when it enters the bloodstream via a bite, and that the fang contains venom in the form of yellow fluid.[3][8] He even showed that by applying a tight ligature before the wound, the passage of venom into the heart could be prevented. This work marked the beginning of experimental toxinology/toxicology.[9][10]

علم الحشرات والتولد اللحظي

Redi is best known for his series of experiments, published in 1668 as Esperienze intorno alla generazione degl'insetti (Experiments on the Generation of Insects), which is regarded as his masterpiece and a milestone in the history of modern science. The book is one of the first steps in refuting "spontaneous generation"—a theory also known as Aristotelian abiogenesis. At the time, the prevailing wisdom was that maggots arose spontaneously from rotting meat.[11]

Redi took six jars and divided them into two groups of three: In one experiment, in the first jar of each group, he put an unknown object; in the second, a dead fish; in the last, a raw chunk of veal. Redi covered the tops of the first group of jars with fine gauze so that only air could get into them. He left the other group open. After several days, he saw maggots appear on the objects in the open jars, on which flies had been able to land, but not in the gauze-covered jars. In the second experiment, meat was kept in three jars. One of the jars was uncovered, and two of the jars were covered, one with cork and the other one with gauze. Flies could only enter the uncovered jar, and in this, maggots appeared. In the jar that was covered with gauze, maggots appeared on the gauze but did not survive.[12][13]

Redi continued his experiments by capturing the maggots and waiting for them to metamorphose, which they did, becoming flies. Also, when dead flies or maggots were put in sealed jars with dead animals or veal, no maggots appeared, but when the same thing was done with living flies, maggots did. His interpretations were always based on biblical passages, such as his famous adage: omne vivum ex vivo ("All life comes from life").[2][14]

علم الطفيليات

Redi was the first to describe ectoparasites in his Esperienze intorno alla generazione degl'insetti. His notable illustrations in the book are those relevant to ticks, including deer ticks and tiger ticks; it also contains the first depiction of the larva of Cephenemyiinae, the nasal flies of deer, as well as the sheep liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica). His next treatise in 1684 titled Osservazioni intorno agli animali viventi che si trovano negli animali viventi (Observations on Living Animals, that are in Living Animals) recorded the descriptions and the illustrations of more than 100 parasites. In it, he also differentiates the earthworm (generally regarded as a helminth) and Ascaris lumbricoides, the human roundworm. An important innovation from the book is his experiments in chemotherapy in which he employed the "control"', the basis of experimental design in modern biological research.[15][2][16] He described some 180 species of parasites. Perhaps, his most significant observation was that parasites produce eggs and develop from them, which contradicted the prevailing opinion that they are produced spontaneously.[17]

السيرة الأدبية

As a poet, Redi is best known for the dithyramb Bacco in Toscana (Bacchus in Tuscany), which first appeared in 1685. His bacchanalian poem in praise of Tuscan wines is still read in Italy today.[3] He was admitted to two literary societies: the Academy of Arcadia and the Accademia della Crusca.[4] He was an active member of Crusca and supported the preparation of the Tuscan dictionary.[18] He taught the Tuscan language as a lettore pubblico di lingua toscana in Florence in 1666. He also composed many other literary works, including his Letters, and Arianna Inferma.[3]

أشياء سميت على اسمه

- Redi, a crater on Mars was named in his honor.[19]

- The larval stage of parasitic fluke called "redia" is named after Redi by another Italian zoologist, Filippo de Filippi, in 1837.[2]

- The Redi Award, the most prestigious award in toxinology, is given in his honour by the International Society on Toxinology. The award is made at each World Congress of IST (generally held every three years) since 1967.[8][20]

- A scientific journal Redia, an Italian journal of zoology, is named in his honour, which was first published in 1903.[21]

- A European viper subspecies, Vipera aspis francisciredi Laurenti, 1768, is named after him.[22]

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ "Francesco Redi". brunelleschi.imss.fi.it (in الإنجليزية). 27 فبراير 2008. Retrieved 10 ديسمبر 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت ث خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةami - ^ أ ب ت ث Hawgood BJ (2003). "Francesco Redi (1626-1697): Tuscan philosopher, physician and poet". Journal of Medical Biography. 11 (1): 28–34. doi:10.1177/096777200301100108. PMID 12522497. S2CID 23575162.

- ^ أ ب Francesco Redi of Arezzo (1909) [1668]. Mab Bigelow (translation and notes) (ed.). Experiments on the Generation of Insects. Chicago: Open Court. ISBN 9780527744007. Retrieved 2 مارس 2010.

- ^ Francesco Redi of Arezzo (1825) [1685]. Leigh Hunt (translation and notes) (ed.). Bacchus in Tuscany. London: Printed by J. C. Kelly for John and H. L. Hunt. Retrieved 2 مارس 2010.

- ^ "Francesco Redi Letters 1683-1693". National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Francesco Redi (1988). Knoefel PK (ed.). Francesco Redi on Vipers. Leiden, the Netherlands: E.J. Brill. pp. 11–17. ISBN 9004089489. Archived from the original on 30 أبريل 2016. Retrieved 18 أبريل 2013.

- ^ أ ب Habermehl GG (1994). "Francesco Redi¬—life and work". Toxicon. 32 (4): 411–417. Bibcode:1994Txcn...32..411H. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(94)90292-5. PMID 8052995.

- ^ Buettner KA (2007). Francesco Redi (The Embryo Project Encyclopedia ). ISSN 1940-5030. Archived from the original on 19 يونيو 2010. Retrieved 18 أبريل 2013.

- ^ Hayes AN, Gilbert SG (2009). "Historical milestones and discoveries that shaped the toxicology sciences". Molecular, Clinical and Environmental Toxicology. Experientia Supplementum. Vol. 99. pp. 1–35. doi:10.1007/978-3-7643-8336-7_1. ISBN 978-3-7643-8335-0. PMID 19157056.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةlev - ^ Redi F. "Esperienze intorno alla generazione degl'insetti fatte da Francesco Redi". Archived from the original on 3 سبتمبر 2012.

- ^ Barnett B (30 سبتمبر 2011). "Francesco Redi and Spontaneous Generation". Archived from the original on 23 مايو 2013. Retrieved 18 أبريل 2013.

- ^ Gottdenker P (1979). "Francesco Redi and the fly experiments". Bull Hist Med. 53 (4): 575–592. PMID 397843.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةlei - ^ Ioli A, Petithory JC, Théodoridès J (1997). "Francesco Redi and the birth of experimental parasitology". Hist Sci Med. 31 (1): 61–66. PMID 11625103.

- ^ Bush AO, Fernández JC, Esch GW, Seed JR (2001). Parasitism: The Diversity and Ecology of Animal Parasites. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 0521664470.

- ^ قالب:CE1913

- ^ SpaceRef (14 أغسطس 2004). "NASA Mars Odyssey THEMIS Image: Promethei Terra". Archived from the original on 30 يونيو 2013. Retrieved 18 أبريل 2013.

- ^ International Society on Toxinology. "IST Redi Awards". Archived from the original on 4 أكتوبر 2013. Retrieved 18 أبريل 2013.

- ^ REDIA – Journal of Zoology. "History". Archived from the original on 4 أكتوبر 2013. Retrieved 18 أبريل 2013.

- ^ Vipera aspis francisciredi (TSN {{{ID}}}). Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

المراجع

- Altieri Biagi, Maria Luisa (1968). Lingua e cultura di Francesco Redi, medico. Florence: L. S. Olschki. ISBN IT\ICCU\SBL\0070073.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help)

وصلات خارجية

- Francesco Redi entry in the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Experiments on the Generation of Insects, translation of the 5th edition (1688)

- Bacco in Toscana (English translation: Bacchus in Tuscany)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Use dmy dates from December 2024

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- CS1 errors: ISBN

- Pages using authority control with unknown parameters

- Persondata templates without short description parameter

- مواليد 1626

- وفيات 1697

- أشخاص من أرتسو

- إيطاليو القرن 17

- علم حشرات إيطاليون

- شعراء إيطاليون

- خريجو جامعة پيزا

- علماء القرن 17

- وضعيون

- أعضاء أكاديمية الأركاديين