كوتريگور

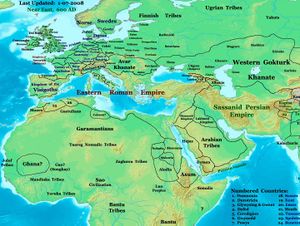

كوتريگور Kutrigurs كانوا بدو خيالة الذين ازدهروا في سهوب پنطس-القزوين في القرن السادس الميلادي. إلى الشرق منهم تواجد الأوتيگور المشابهون. وقد حاربوا الامبراطورية البيزنطية والأوتيگور. وقرب نهاية القرن السادس كان الآڤار قد استوعبوهم بضغط من الترك.

أصل الاسم

The name Kutrigur, also recorded as Kwrtrgr, Κουτρίγουροι, Κουτούργουροι, Κοτρίγουροι, Κοτρίγοροι, Κουτρίγοροι, Κοτράγηροι, Κουτράγουροι, Κοτριαγήροι,[1] has been suggested as a metathecized form of Turkic *Toqur-Oğur, thus the *Quturoğur mean "Nine Oğur (tribes)".[2] David Marshall Lang derived it from Turkic kötrügür (conspicuous, eminent, renowned).[3] There has been little scholarly support for theories linking the names of Kutrigurs and Utigurs to peoples such as the Guti/Quti and/or Udi/Uti, of Ancient Southwest Asia and the Caucasus respectively, which has been posited by Osman Karatay,[4] or Duč'i (some read Kuchi) Bulgars by Josef Markwart.[5]

التاريخ

Grousset thought that the Kutrigurs were remnants of the Huns,[6] Procopius recounts:

in the old days many Huns,[nb 1] called then Cimmerians, inhabited the lands I mentioned already. They all had a single king. Once one of their kings had two sons: one called Utigur and another called Kutrigur. After their father's death they shared the power and gave their names to the subjected peoples, so that even nowadays some of them are called Utigurs and the others - Kutrigurs.[9][10]

They occupied the Tanaitic-Maeotic (Don-Azov) steppe zone, the Kutrigurs in the Western part and the Utrigurs towards the East.[11] This story was also confirmed by the words of the Utigur ruler Sandilch:

It is neither fair nor decent to exterminate our tribesmen (the Kutrigurs), who not only speak a language, identical to ours, who are our neighbours and have the same dressing and manners of life, but who are also our relatives, even though subjected to other lords".[9]

Agathias Scholasticus, Greek poet and the principal historian of part of the reign of the Roman emperor Justinian I. recalls the origin of their name as follows:

"In ancient times the Huns inhabited the region east of lake Maeotis to the north of the river Don, as did the rest of the barbarian peoples established in Asia on the near side of Mount Imaeus. All these peoples were referred to by the general name of Scythians or Huns, whereas individual tribes had their own particular names, rooted in ancestral tradition, such as Cotrigurs, Utigurs, Ultizurs, Bourougounds and so on and so forth."[12]

The Syriac translation of Pseudo-Zacharias Rhetor's Ecclesiastical History (ح. 555) in Western Eurasia records thirteen tribes, the wngwr (Onogur), wgr (Oğur), sbr (Sabir), bwrgr (Burğar, i.e. Bulgars), kwrtrgr (Kutriğurs), br (probably Abar, i.e. Avars), ksr (Kasr; Akatziri?), srwrgwr (Saragurs), dyrmr (*[I]di[r]mar? < Ιτιμαροι),[13] b'grsyq (Bagrasik, i.e. Barsils), kwls (Khalyzians?), bdl (Abdali?), and ftlyt (Hephthalite). They are described in typical phrases used for nomads in the ethnographic literature of the period, as people who "live in tents, earn their living on the meat of livestock and fish, of wild animals and by their weapons (plunder)".[9][14]

War with the Byzantines

...all of them are called in general Scythians and Huns in particular according to their nation. Thus, some are Koutrigours or Outigours and yet others are Oultizurs and Bourougounds... the Oultizurs and Bourougounds were known up to the time of the Emperor Leo (457–474) and the Romans of that time and appeared to have been strong. We, however, in this day, neither know them, nor, I think, will we. Perhaps, they have perished or perhaps they have moved off to very far place.[15]

In 551, a 12,000-strong Kutrigur army led by many commanders, including Chinialon, came from the "western side of the Maeotic Lake" to assist the Gepids who were at the war with the Lombards.[16] Later, with the Gepids, they plundered the Byzantine lands.[16] Emperor Justinian I (527–565) through diplomatic persuasion and bribery tricked the Kutrigurs and Utigurs into mutual warfare.[17][10] Utigurs led by Sandilch attacked the Kutrigurs, who suffered great losses.[10]

Kutrigurs made a peace treaty with the Byzantine Empire, and 2,000 Kutrigurs on horseback, with wives and children, led by Sinnion, entered imperial service and were settled in Thrace.[10][16] The friendly treatment of those Kutrigurs was viewed negatively by Sandilch.[10]

In the winter of 558, the remaining large Kutrigur army led by Zabergan crossed the frozen Danube and divided into three sections; one raided south as far as Thermopylae; while two others the Thracian Chersonesus; and the periphery of Constantinople.[18] In March 559 Zabergan attacked Constantinople; one part of his forces consisted of 7,000 horsemen.[19] The transit of such distances in a short period of time shows that they were mounted warriors,[18] and compared to the Chinialon's army, Zabergan's raiders were already encamped near the banks of the Danube.[18]

A threat to the stability of the Byzantine Empire according to Procopius, Agathias and Menander, the Kutrigurs and Utigurs decimated one another.[10] Some Kutrigur remnants were swept away by the Avars to Pannonia. By 569 the Κοτζαγηροί (Kotzagiroi, possibly Kutrigurs), Ταρνιάχ (Tarniach) and Ζαβενδὲρ (Zabender) fled to the Avars from the Türks.[10] Avar Khagan Bayan I in 568 ordered 10,000 so-called Kutrigur Huns to cross the Sava river.[20] The Utigurs remained in the Pontic steppe and fell under the rule of the Türks.[21][6]

Between 630 and 635, Khan Kubrat managed to unite the Onogur Bulgars with the tribes of the Kutrigurs and Utigurs under a single rule, creating a powerful confederation which was referred to by the medieval authors in Western Europe as Old Great Bulgaria,[22] or Patria Onoguria. According to some scholars, it is more correctly called the Onogundur-Bulgar Empire.[23]

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

الهامش

- ^ Golden 2011, p. 139.

- ^ Golden 2011, p. 71, 139.

- ^ Lang 1976, p. 34.

- ^ Karatay 2003, p. 26.

- ^ Vasil 1918.

- ^ أ ب Grousset 1970, p. 79.

- ^ Beckwith 2009, p. 99.

- ^ Dickens 2004, p. 19.

- ^ أ ب ت Dimitrov 1987.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Golden 2011, p. 140.

- ^ Golden 1992, p. 99.

- ^ Agathias. Agathias: The Histories. Translated by Frendo, Joseph D.

- ^ Peter B. Golden (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic People. O. Harrassowitz. p. 505

- ^ Golden 1992, p. 97.

- ^ Golden 1992, p. 98.

- ^ أ ب ت Curta 2015, p. 76.

- ^ Golden 1992, p. 99–100.

- ^ أ ب ت Curta 2015, p. 77.

- ^ Golden 2011, p. 107.

- ^ Dickens 2010, p. 5.

- ^ Golden 2011, p. 140–141.

- ^ Patriarch Nikephoros I of Constantinople, Historia syntomos, breviarium

- ^ Zimonyi Istvan: "History of the Turkic speaking peoples in Europe before the Ottomans". (Uppsala University: Institute of Linguistics and Philology) (archived from the original Archived 2012-07-22 at the Wayback Machine on 2013-10-21)

- المصادر

- Golden, Peter Benjamin (1992). An introduction to the History of the Turkic peoples: ethnogenesis and state formation in medieval and early modern Eurasia and the Middle East. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. ISBN 9783447032742.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Lang, David Marshall (1976). The Bulgarians: from pagan times to the Ottoman conquest. Westview Press. ISBN 9780891585305.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Karatay, Osman (2003). In Search of the Lost Tribe: The Origins and Making of the Croation Nation. Ayse Demiral. ISBN 9789756467077.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Zlatarski, Vasil (1918). History of the Bulgarian state in the Middle Ages, Volume I. History of the First Bulgarian Kingdom. Part I. Age of Hun-Bulgarian supremacy (679-852) (in Bulgarian). Sofia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. The State University of New Jersey. ISBN 9780813513041.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400829941.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Dickens, Mark (2004). Medieval Syriac Historians’ Perceptionsof the Turks. University of Cambridge.

- D. Dimitrov (1987). "Bulgars, Unogundurs, Onogurs, Utigurs, Kutrigurs". Prabylgarite po severnoto i zapadnoto Chernomorie. Varna.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Golden, Peter B. (2011). Studies on the Peoples and Cultures of the Eurasian Steppes. Editura Academiei Române; Editura Istros a Muzeului Brăilei. ISBN 9789732721520.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Curta, Florin (2015). "Avar Blitzkrieg, Slavic and Bulgar raiders, and Roman special ops: mobile warriors in the 6th-century Balkans". In Zimonyi István; Osman Karatay (eds.). Eurasia in the Middle Ages. Studies in Honour of Peter B. Golden. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. pp. 69–89.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Dickens, Mark (2010). The Three Scythian Brothers: an Extract from the Chronicle of Michael the Great.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)