ني أوسر رع إيني

| Nyuserre Ini | |

|---|---|

| Niuserre Ini, Neuserre Ini, Nyuserra, Newoserre Any, Rathoris | |

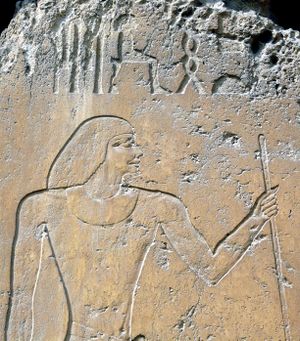

Double statue portraying Nyuserre as both a young man and an old man, Museum of Egyptian Art in Munich | |

| فرعون | |

| الحكم | Around 36 years, ح. 2458 - ح. 2422 BC[note 1][note 2] |

| سبقه | Shepseskare (most likely) or Neferefre |

| تبعه | Menkauhor Kaiu or Shepseskare (Nuzzolo) |

| القرينة | Reptynub and at least 1 other spouse |

| الأنجال | Possibly Khamerernebty, Sheretnebty, Khentykauhor and/or 1 son |

| الأب | Neferirkare Kakai |

| الأم | Khentkaus II |

| المدفن | Pyramid of Nyuserre Ini, Giza, Egypt |

| الآثار | Built ex-nihilo: Pyramid of Nyuserre Ini Pyramid Lepsius XXIV Lepsius XXV Sun temple Shesepibre Completed: Pyramid of Neferirkare Kakai Pyramid of Neferefre Pyramid complex of Khentkaus II Sun temple of Userkaf Renovated: Mortuary complex of Menkaure Uncertain: Temple of Satet |

ني أوسر رع إيني بالإنجليزية Nyuserra ، ويسمى في اليونانية راثوريس Rathurês, Ῥαθούρης، توفي حوالي 2422 ق.م.) هو سادس ملك فرعوني في الأسرةالمصرية الخامسة في فترة الدولة القديمة. وقد تولى الحكم لمدة ما بين 24-36 عام، حسب الدارس، وعاش غالباً في النصف الثاني من القرن 25 ق.م.. وكان أصغر أبناء Neferirkare Kakai والملكة Khentkaus II, and the brother of the short-lived king Neferefre. He may have succeeded his brother directly, as indicated by much later historical sources. Alternatively, Shepseskare may have reigned between the two as advocated by Miroslav Verner, albeit only for a few weeks or months at the most. The relation of Shepseskare with Neferefre and Nyuserre remains highly uncertain. Nyuserre was in turn succeeded by Menkauhor Kaiu, who could have been his nephew and a son of Neferefre.

وإسم ميلاده يعني الملك من قوة رع. والملك ني أوسر رع هو ابن للملك نفر إر كا رع (كاكاي) من زوجته الملكة خنت كاوس الثانية وأخيه الملك نفر إف رع.

Nyuserre was the most prolific builder of his dynasty, having built three pyramids for himself and his queens and completed a further three for his father, mother and brother, all in the necropolis of Abusir. He built the largest surviving temple to the sun god Ra constructed during the Old Kingdom, named Shesepibre or "Joy of the heart of Ra". He also completed the Nekhenre, the Sun temple of Userkaf in Abu Gorab, and the valley temple of Menkaure in Giza. In doing so, he was the first king since Shepseskaf, last ruler of the Fourth Dynasty, to pay attention to the Giza necropolis, a move which may have been an attempt to legitimise his rule following the troubled times surrounding the unexpected death of his brother Neferefre.

There is little evidence for military action during Nyuserre's reign; the Egyptian state continued to maintain trade relations with Byblos on the Levantine coast and to send mining and quarrying expeditions to Sinai and Lower Nubia. Nyuserre's reign saw the growth of the administration, and the effective birth of the nomarchs, provincial governors who, for the first time, were sent to live in the provinces they administered rather than at the pharaoh's court.

قام بإنابة "وزير" Tjati لمتابعة مرافق الحياة في البلاد . كما أرسل بعثات حربية إلى وادي المغارة بسيناء وإلى النوبة لتأمين محاجر استخراج النحاس و الذهب ؛ وكانت له علاقات تجارية مع جبيل (في لبنان اليوم) . عدل الطقوس الدينية وبصفة خاصة في الطقوس الجنائزية للملك بعد وفاته ، واتبعت تلك الطقوس حتى عصر الدولة المصرية الوسطى.

As with other Old Kingdom pharaohs, Nyuserre benefited from a funerary cult established at his death. In Nyuserre's case, this official state-sponsored cult existed for centuries, surviving the chaotic First Intermediate Period and lasting until the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom. In parallel, a spontaneous popular cult appeared, with people venerating Nyuserre under his birth name "Iny". In this cult, Nyuserre played a role similar to that of a saint, being invoked as an intercessor between the believer and the gods. It left little archaeological evidence and seems to have continued until the New Kingdom, nearly 1,000 years after his death.

المصادر

المصادر المعاصرة له

Nyuserre Ini is well attested in sources contemporaneous with his reign,[note 3] for example in the tombs of some of his contemporaries including Nyuserre's manicurists Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum, the high officials Khufukhaf II, Ty, Rashepses, Neferefre-ankh and Khabawptah,[26][27] and the priests of his funerary cult Nimaatsed and Kaemnefert.[28][29]

المصادر التاريخية

Nyuserre is attested in three ancient Egyptian king lists, all dating to the New Kingdom. The earliest of these is the Karnak king list, which was commissioned by Thutmose III (fl. 1479–1425 BCE) to honour some of his forebears and which mentions Nyuserre in the fourth entry, which shows his birth name "Iny" in a cartouche.[30] Nyuserre's prenomen occupies the 30th entry of the Abydos King List, written nearly 200 years later during the reign of Seti I (fl. 1290–1279 BCE). Nyuserre's prenomen was most likely also given on the Turin canon (third column, 22nd row), dating to the reign of Ramses II (fl. 1279–1213 BCE), but it has since been lost in a large lacuna affecting the document. Fragments of his reign length are still visible on the papyrus, indicating a reign of somewhere between 11 and 34 years.[31] Nyuserre is the only Fifth Dynasty king absent from the Saqqara Tablet.[32]

Nyuserre was also mentioned in the Aegyptiaca, a history of Egypt probably written in the 3rd century BCE during the reign of Ptolemy II (fl. 283–246 BCE) by the Egyptian priest Manetho. Even though no copies of the text survive, it is known through later writings by Sextus Julius Africanus and Eusebius. In particular, Africanus relates that the Aegyptiaca mentioned a pharaoh ´Ραθούρης, that is "Rathurês", reigning for forty-four years as the sixth king of the Fifth Dynasty.[33] "Rathurês" is believed to be the Hellenised form of Nyuserre.[34]

نظام الحكم

عمل ني-أوسر-رع على تركيز حكم البلاد وتوكيلها إلى "وزير" يقوم بأعلى وظائف القصر ويرعاها . فجمع وظيفة "رئيس غرفتي الثروة " ، و "رئيس الشونتين" ، و"رئيس غرفتي حلي الملك " في يد وزير Tjati .

بذلك تجمعت كل شئون البلاط الملكي في وظيفة واحدة . كما ظهرت في عهده أيضا وظيفتين جديدتين حملهما وزير يدعى "كاي " ، فكان هذا "رئيسا للبيت العالي " بوظيفة قضائية ، ثم رقي إلى مرتبة وزير بلقب " رئيس 6 البيوت الكبيرة" وكبير القضاة على مصر. كما حمل "كاي" أيضا لقب "محافظ مصر العليا" . [35]

كذلك يذكر التاريخ تقليد "من نفر" [36] و بتاح شبسيس مقاليد الوزارة أثناء حكم ني-أوسر-رع. كما يشير بعض علماء الآثار أن الوزير "سخم عنخ بتاح" كان أيضا أثناء حكم ني-أوسر-رع [37] . وكان بتاح شبسيس قد وصل إلى أعلى المراتب في الدولة بزواجه من الأميرة "غاميرر نبتي" ويدل على ذلك مقبرته التي بناها والتي تعتبر أكبر مقبرة خاصة من الدولة القديمة . [38]

>

العلاقات التجارية والحملات

توجد في وادي المغارة بسيناء لوحتان منقوشتان في الصخور من عهد ني-أوسر-رع. اخذت أحدهما إلى المتحف المصري بالقاهرة .[39] تدل اللوحتين على استغلال ني-أوسر-رع استخراج النحاس و احجار الفيروز الكريمة من منطقة هذا الوادي . [40]

وكانت للملك علاقات تجارية مع بلاد الشام ، وتدل عليها تبادل التجارة مع جبيل على البحر الأبيض المتوسط ، وتقع حاليا في لبنان ، حيث عثر فيها على أحد تماثيل "ني-أوسر-رع" ، وكذلك من شقفة قارورة من مدينة "ترافرتين " تحمل اسمه . [41][42]

ويدل على نشاطه في الجنوب في النوبة والعثور على ختم كان موجودا في قلعة بوهين عند الشلال الثاني على النيل . [43] . كما وجد جزء من لوحة حجرية نقش عليها اسم الملك ني-أوسر-رع وجدت في أحد محاجر الجنيس (نوع من أحجار فلدسبار). [44]

آثاره

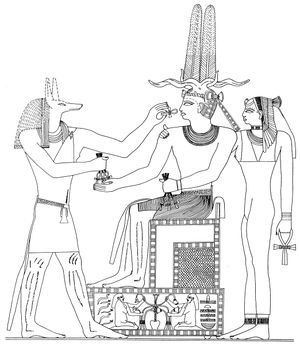

قام بتشييد هرمه بمنطقة أبو صير (بارتفاع 52 مترا)، ومعبد الشمس بالقرب منه بمنطقة أبو غراب. وتصور النقوش التي تزين هذا المعبد الإحتفالات الخاصة بعيد "الحب سد" وهو نوع من اليوبيل الملكي. كما توضح هذه النقوش المذهب الطبيعي الذي كان سائدا في ذلك الوقت. إذ تصور "حجرة العالم" الفصول الثلاثة الرئيسية للعام أي الفيضان والشتاء والصيف، وحياة الخلق والإبداع الذين عمر بهما الإله رع الأراضي المصرية: مثل نماء المزروعات وتناسل وتوالد الحيوانات، وأوجه نشاط البشر. وعلى الرغم مما لحق بهما من تلف بالغ، تكشف لنا تلك النقوش عن سلامة فطرة الملاحظة لدى المصريين. فقد قاموا بملاحظة وتدوين عملية الإنتقال الدوري لسمك البوري من المياه المالحة في المستنقعات البحرية إلى المياه العذبة للشلال الأول في إلفنتين، بالإضافة إلى أن مختلف الإشارات توحي بأن حكم الملك ني اوسر رع هو ذروة العظمة في الأسرة الخامسة.[45]

كما قام ببناء معبد الشمس في منطقة أبو غراب في الجزء الشمالي من أبو صير.

بعد وفاة ني أوسر رع فقدت منطقة أبو صير موقعها كمنطقة لمقابر المفراعنة. فكان هو آخر فرعون يبني مقبرته فيها. وبنى خليفته من-كا-حور مقبرته في سقارة.[46] إلا أن الملك "جد-كا-رع " قام ببناء مقابر عائلته في أبي صير. [47]

تكملته لمنشآت من سبقوه

هرم نفر-ير- كا-رع

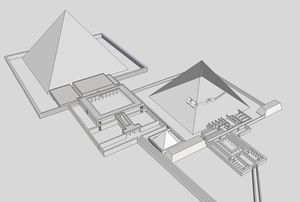

يبلغ طول وعرض قاعدة هذا الهرم 105 متر وكان ارتفاعه 72 متر ، حيث أراد نفر يركا رع بناء منشآت تفوق من سبقه . وتوفي مبكرا وترك تغطية الهرم والمنشأت حوله لم تكتمل . ومن المحتمل أن يكون تكملة المعبد الجنائزي له قد تمت في عهد "رع-نفر-إف" في ناحية الشرق.

ويبدو أن ني-أوسر-رع لم يكن هو من قام ببناء طريق المراسيم بين معبد الوادي و المعبد الجنائزي ل "نفر-ير-كا-رع" . ولكنه بني قام ببناء منشآت للكهنة في جنوب المعبد الجنائزي ، وأرشيف ، حيث عثر فيها على برديات أبو صير. [48]

هرم خنتكاوس الثانية

بوفاة الملك "نفر-ير كا-رع" توقفت عمليات بناء هرم زوجته الملكة "خنتكاوس الثانية" أيضا. ومن كتابات العمال على احجار الهرم نعرف أن نصف الهرم تقريبا قد تم بناه خلال السنة 10 أو 11 من حكم "نفر-ير-كا-رع". لم تكتمل بنية هرم خنتكاوس الثانية خلال حكمي "رع-نفر-إف" و " "شيسيس-كا-رع" ، وقام :ني-أوسر -رع" بتكملته. اكمل التغطية بالحجر الجيري الأبيض ، وبنى ععند وادهته الشرقية المعبد الجنائزي لهذا الهرم الخاص بأمه.

كما قام ببناء هرم صغير في الجزء الجنوبي الشرقي من هرم أمه "خنتكاوس الثانية " ليكون مصلى للعبادة ، وكان ذلك تجديدا للطقوس ، حيث كانت الأهرامات الصغيرة المجاورة لالفرعون تختص فقط بالملوك. كما أحاط مجمع الأهرامات لأمه بحائط يفصله عن هرم "نفر-ير-كا-رع". [49][50]

هرم رع-نفر-إف

عندما توفي "رع-نفر-إف" بعد فتر حكم قصيرة لم يكن من هرمه سوي مصطبة جاهزة علوها نحو 7 أمتار. لهذا ألغي التصميم الأصلي وتحول البناء بالفعل إلى مصطبة. وبعد تقلد ني-أوسر-رع مقاليد الحكم قام بتكملة عمليات البناء فيها بالطوب اللبن . كما بنى في الجزء الشرقي للمعبد الجنائزي الحجري حجرات مخازن ، وفي جنوبه قام ببناء بهو مسقوف بالخشب مزين بالنجوم ومرفوع عل أعمدة خشبية مزينة ققمها في هيئة زهرة اللوتس.

وأحاط مجمع المصطبة ومعبدها بحائط ، واقام في شرقها مذبحا للمراسيم الجنائزية . هذا التصميم الأولي قام ني-أوسر-رع بعد ذلك بتغييره أثناء العمليات الأخيرة للبناء وجعل المنشأت في هيئة حرف T ، وظل هذا التصميم متبعا لتصميمات المعابد الجنائزية لملوك الاسرة الخامسة الذين حكموا من بعده.

وبنى في الشرق بهو آخر خشبي مسقوف ومرفوع على 22 من الأعمدة ، مزود ببهو في المدخل ، وزود المدخل بعمودين من الحجر الجيري في هيئة نبات البردي . ولكنه لم يكمل بناء معبد الوادي لهذا المجمع وتوصيلهما بطريق للطقوس الجنائزية .[51]

إنشاءاته الخاصة

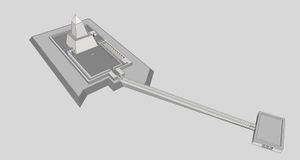

هرم ني-أوسر-رع

| . |

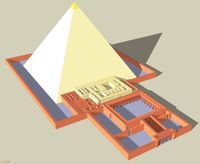

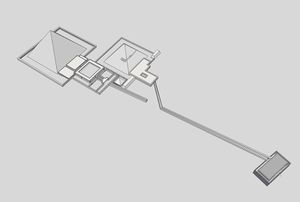

لبناء مجمع هرمه اختار نيج-وسر-رع مكانا بين هرم ابيه "نفر-ير-كا-رع" و هرم جده ساحورع . يبلغ ضلع قادة هرمه 5و78 متر، وهو بنفس مساحة قادة هرم ساحو رع . يتكون قلب الهرم من الحجر الجيري التي كونت من 7 مصاطب فوق بعضها البعض ، وغطيت من الخارج بالحجر الجيري الأ بيض.

يوجد مدخل الهرم في الجزء الشمالي . ويتبع المدخل دهليز يتعوج يمينا ويسارا يؤدي إلى حجرة أولية . يوجد في وسط هذا الممر تظام للإغلاق بكتلة حجرية ضخمة من الجرانيت (يستعان في إغلاقها بتسريب رمل أسفل الكتلة ، يتسرب في غرفتين صغيرتين على الجانبين ، فتسقط كتلة الإغلاق). يوجد ممر متفرع من الحجرة الأولى من الناحية الغربية يؤدي إلى حجرة الدفن .

كل من الحجرتين مسقوف بثلاثة طوابق من الأسقف الحجرية الكبيرة في شكل السرج وهي من الحدجر الجيري. ونظرا لأن مكونات الهرم قد سرقت وأخذ منه أحجارا كثيرة فيصعب معرفة شكل الغرفتين تماما. كما لم يعثر على أثاث أو حلي في الحجرتين .

يتميز المعبد الجنائزي لهرم ني-أوسر-رع بانزياح جهته الشرقية نحو الجنوب ، وبهذا لا تتخذ قاعدة المعبد الشكل T وأنما في شكل حرف L . يحيط بهدا الجزء الشرقي حجرات مخازن وبهو مسقوف وبهو مفتوح تحيطه اعمدة . كما يفصل دهليز بين الجزء الشرقي للمعبد وجزئه الغربي ، والذي تقام فيه الطقوس الجنائزية . عثر في هذا الدهليز على بقايا تمثال في شكل الأسد .

ومن التصميمات الفريدة ل "ني-أوسر-رع" غرفة مربعة يتوسطها عمود ، وتتصل ببهو للقرابين ، وقد اتبع هذا التصميم بعد ذلك خلال حكم من خلفوا ني_أوسر-رع وحتى الدولة المصرية الوسطى وما يرتبط بها من طقوس.

وبنى هرم صغير للعبادة عند الركن الجنوبي الشرقي للهرم . وأحاط مجمع الأهرام بحائط وعززة بزوايا قوية غند الجنوب والشمال الشرقيين. تلك التعزيزات تعتبر التصميم المبدئي الذي اتخذته بعد ذلك تصميم الصراح.

أما معبد الوادي الذي كان واقعا على النيل فقد بدأ بناؤه في عهد أبيه "نفر-ير-كا-بع" ، فأكمله ني أوسر رع ، كما اكمل طريق الطقوس المؤدي إلى هرمه وهرم أبيه. يوجد لمعبد الوادي مدخلان : مدخل من الشرق ، حيث كان يوجد الميناء في القديم ، ومدخل في الغرب. ويتكون وسط المعبد من حجرة لها نيشات عديدة (محاريب) يعتقد أنها كانت تحوي تماثيل للملك ، وعثر بالقرب منها على رأس تمثال لأحد زوجاته ، وهي الملكة "ربوت- نبو" وبقايا تماثيل لأعدائه الذين هزمهم .[52]

سنوات حكمه

| الكاتب | سنوات الحكم |

|---|---|

| ردفورد | 2474 ق.م. - 2444 ق.م. |

| كراوس | 2455 ق.م. - 2420 ق.م. |

| شو | 2445 ق.م. - 2421 ق.م. |

| شنايدر | 2440 ق.م. - 2415 ق.م. |

| دودسون | 2432 ق.م. - 2421 ق.م. |

| فون بكرات | 2420 ق.م. - 2380 ق.م. |

| آلن | 2420 ق.م. - 2389 ق.م. |

| مالك | 2408 ق.م. - 2377 ق.م. |

انظر أيضا

وصلات خارجية

الملاحظات والهامش والمصادر

ملاحظات شارحة

- ^ Proposed dates for Nyuserre's reign: 2474–2444 BCE,[1][2][3] 2470–2444 BCE,[4] 2465–2435 BCE,[5] 2453–2422 BCE,[6] 2453–2420 BCE,[7] 2445–2421 BCE,[8][9][10] 2445–2414 BCE,[11] 2420–2389 BCE,[12] 2402–2374 BCE,[13][14] 2398–2388 BCE.[15] In a 1978 work, the Egyptologist William C. Hayes credited Nyuserre with 30+2(?) years of reign, starting ح. 2500 BCE.[16]

- ^ The only date known reliably in relation with Nyuserre Ini comes from radiocarbon dating of a piece of wood discovered in the mastaba of Ptahshepses, a vizier and son in law of Nyuserre. The wood was dated to 2465–2333 BCE.[17][18]

- ^ Numerous artefacts and architectural elements either bearing Nyuserre's nomen, prenomen or serekh or simply contemporary with his reign have been unearthed. These are now scattered throughout the world in many museums including the Boston Museum of Fine Arts,[21] Brooklyn Museum,[22] Los Angeles County Museum of Art,[3] Metropolitan Museum of Art,[23] Petrie Museum,[24][25] the Egyptian Museum of Cairo and many more.

الهامش

- ^ Verner 2001b, p. 589.

- ^ Hawass & Senussi 2008, p. 10.

- ^ أ ب LACMA 2016.

- ^ Altenmüller 2001, p. 599.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica 2016.

- ^ Clayton 1994, p. 60.

- ^ Ziegler 2007, p. 215.

- ^ Malek 2000a, p. 100.

- ^ Rice 1999, p. 141.

- ^ Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 55.

- ^ Strudwick 2005, p. xxx.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, p. 283.

- ^ Hornung 2012, p. 491.

- ^ Nolan 2012, p. 3.

- ^ Strudwick 1985, p. 3.

- ^ Hayes 1978, p. 58.

- ^ Verner 2001a, p. 404.

- ^ von Beckerath 1997, p. 56.

- ^ Clayton 1994, p. 61.

- ^ Leprohon 2013, p. 40.

- ^ Boston Museum of fine Arts 2016.

- ^ Brooklyn Museum 2016.

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art 2016.

- ^ Petrie Museum 2016, UC11103.

- ^ Digital Egypt for Universities 2016.

- ^ Mariette 1885, pp. 294–295.

- ^ de Rougé 1918, p. 89.

- ^ Mariette 1885, pp. 242–249.

- ^ de Rougé 1918, p. 88.

- ^ Morales 2006, p. 320.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, p. 13.

- ^ Mariette 1864, pl. 17.

- ^ Waddell 1971, p. 51.

- ^ Verner 2001a, p. 401.

- ^ Petra Andrassy: Untersuchungen zum ägyptischen Staat des Alten Reiches und seinen Institutionen (= Internetbeiträge zur Ägyptologie und Sudanarchäologie. Band XI). Berlin/London 2008 (PDF; 1,51 MB), S. 36–37.

- ^ Petra Andrassy: Zur Organisation und Finanzierung von Tempelbauten im Alten Ägypten. In: Martin Fitzenreiter (Hrsg.): Das Heilige und die Ware. Zum Spannungsfeld von Religion und Ökonomie (= Internet-Beiträge zur Ägyptologie und Sudanarchäologie. Band 7). Golden House, London 2007, S. 147–148 (PDF; 10,9 MB).

- ^ Berta Porter, Rosalind L. B. Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. III. Memphis. 2. Auflage. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1974 (PDF 30,5 MB), S. 191.

- ^ Miroslav Verner: Verlorene Pyramiden, vergessene Pharaonen. Abusr. Akademie der Wissenschaften der Tschechischen Republik, Philosophische Fakultät der Karlsuniversität, Tschechisches Ägyptologisches Institut, Prag 1994, S.173–192.

- ^ ألان جاردنر, Thomas Eric Peet, Jaroslav Černý: The Inscriptions of Sinai Band 2: Translations and commentary (= Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund. Bd. 45, ISSN 0307-5109 ). 2nd edition, revised and augmented by Jaroslav Černý, Egypt Exploration Society, London 1955, Nr. 10–11.

- ^ Thomas Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen. S. 183.

- ^ Maurice Dunand: Foulles de Byblos. Band 1, Paul Geuthner, Paris 1939, S. 280.

- ^ Karin N. Sowada: Egypt in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Old Kingdom. An Archaeological Perspective (=Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis. Band 237). Academic Press Fribourg/Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Fribourg/Göttingen, 2009, ISBN 978-3-7278-1649-9, S. 131, Nr. 152.

- ^ Peter Kaplony: Die Rollsiegel des Alten Reiches. Band 2. Katalog der Siegel (= Monumenta Aegyptiaca. Band 3A). Fondation Ègyptologique Reine Élisabeth, Brüssel 1981, S. 251–252, Taf. 74.

- ^ Ian Shaw, Elisabeth Bloxam: Survey and Excavation at the Ancient Pharaonic Gneiss Quarrying Site of Gebel el-Asr, Lower Nubia. In: Sudan and Nubia. Band 3, 1999, S. 13–20.

- ^ پاسكال ڤيرنوس (1999). موسوعة الفراعنة. دار الفكر.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hana Vymazalová, Filip Coppens: König Menkauhor. Ein kaum bekannter Herrscher der 5. Dynastie. In: Sokar Nr. 17, 2008, S. 35–36.

- ^ Miroslav Verner, Vivienne G. Callender: Abusir VI. Djedkare's Family Cemetery. In Excavations of the Czech Institute of Egyptology. Bd. 6, Prag 2002 (PDF; 38,7 MB).

- ^ Miroslav Verner: Die Pyramiden. S. 324–331.

- ^ Miroslav Verner: Die Pyramiden. S. 332–336.

- ^ Miroslav Verner: Further Thoughts on the Khentkaus Problem. In: Discussions in Egyptology. Bd. 38, 1997, ISSN 0268-3803, S. 109–117 (PDF; 2,8 MB).

- ^ Miroslav Verner: Die Pyramiden. S. 341–345.

- ^ Miroslav Verner: Die Pyramiden. S. 346–355.

مصادر عامة

- AFP (4 January 2015). "Tomb of previously unknown pharaonic queen found in Egypt". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (1990). "Bemerkungen zur Gründung der 6. Dynastie". Hildesheimer Ägyptologische Beiträge. Festschrift Jürgen von Beckerath zum 70. Geburtstag am 19. Februar 1990 (in الألمانية). Hildesheim: Pelizaeus-Museum. 30: 1–20.

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (2001). "Old Kingdom: Fifth Dynasty". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 597–601. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Baer, Klaus (1960). Rank and Title in the Old Kingdom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-03412-6.

- Baker, Darrell (2008). The Encyclopedia of the Pharaohs: Volume I – Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty 3300–1069 BC. Stacey International. ISBN 978-1-905299-37-9.

- Bárta, Miroslav (2018). "Egypt's Old Kingdom: The Latest Discoveries at Abusir South". Presentation given at the Harvard Semitic Museum. Archived from the original on 2021-11-14.

- Baud, Michel; Dobrev, Vassil (1995). "De nouvelles annales de l'Ancien Empire Egyptien. Une "Pierre de Palerme" pour la VIe dynastie" (PDF). Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in الفرنسية). 95: 23–92. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Baud, Michel (1999a). Famille Royale et pouvoir sous l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Tome 1 (PDF). Bibliothèque d'étude 126/1 (in الفرنسية). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0250-7.

- Baud, Michel (1999b). Famille Royale et pouvoir sous l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Tome 2 (PDF). Bibliothèque d'étude 126/2 (in الفرنسية). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0250-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015.

- Bissing, Friedrich Wilhelm von; Kees, Hermann; Borchardt, Ludwig (1905–1928). Das Re-Heiligtum des Königs Ne-Woser-Re (Rathures), I, II, III (in الألمانية). Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs. OCLC 78854326.

- Bissing, Friedrich Wilhelm von (1955). "La chambre des trois saisons du sanctuaire solaire du roi Rathourès (Ve dynastie) à Abousir". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. 53: 319–338.

- Borchardt, Ludwig (1907). Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Ne-user-re'. Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft in Abusir 1902–1904 (in الألمانية). Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs. OCLC 6724337.

- Borchardt, Ludwig (1911). Catalogue Général des Antiquités Égyptiennes du Musée du Caire Nos 1–1294. Statuen und Statuetten von Königen und Privatleuten. Teil 1 (PDF) (in الألمانية). Berlin: Reichsdruckerei. OCLC 71385823.

- Borchardt, Ludwig (1913). Das Grabdenkmal des Königs S'aḥu-Re (Band 2): Die Wandbilder: Abbildungsblätter (in الألمانية). Leipzig: Hinrichs. ISBN 978-3-535-00577-1.

- Bothmer, Bernard V. (1974). "The Karnak statue of Ny-user-ra : Membra dispersa IV". Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Abteilung Kairo. Mainz am Rhein: Philip von Zabern. 30: 165–170.

- Brewer, Douglas J.; Teeter, Emily (1999). Egypt and the Egyptians. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44518-4.

- Brovarski, Edward (2001). Der Manuelian, Peter; Simpson, William Kelly (eds.). The Senedjemib Complex, Part 1. The Mastabas of Senedjemib Inti (G 2370), Khnumenti (G 2374), and Senedjemib Mehi (G 2378). Giza Mastabas. Vol. 7. Boston: Art of the Ancient World, Museum of Fine Arts. ISBN 978-0-87846-479-1.

- Callender, Vivienne (1992). "Volume III: A prosopographical register of the wives of Egyptian kings (Dynasties I-XVII)". The wives of the Egyptian kings: dynasties I-XVII (PhD). Macquarie University. OCLC 221450400. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- Clayton, Peter (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05074-3.

- "Czech expedition discovers the tomb of an ancient Egyptian unknown queen". Charles University website. 21 January 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- de Rougé, Emmanuel (1918). Maspero, Gaston; Naville, Édouard (eds.). Œuvres diverses, volume sixième (PDF). Bibliothèque égyptologique (in الفرنسية). Vol. 21–26. Paris: Editions Ernest Leroux. OCLC 39025805.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-05128-3.

- Dreyer, Günter (1986). Elephantine VIII: der Tempel der Satet: die Funde der Frühzeit und des alten Reiches. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen (in الألمانية). Vol. 39. Mainz am Rhein: Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-0501-3.

- Dunand, Maurice (1939). Fouilles de Byblos I. 1926–1932. Direction de l'instruction publique et des beaux-arts; Études et documents d'archéologie (in الفرنسية). Paris: P. Geuthner, Librarie Adrien Maisonneuve. OCLC 79292312.

- Gardiner, Alan (1959). The Royal Canon of Turin. Griffith Institute. OCLC 21484338.

- Goelet, Ogden (1999). "Abu Gurab". In Bard, Kathryn; Shubert, Stephen Blake (eds.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 85–87. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Ian Shaw. Oxford: Blackwell publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8.

- Hawass, Zahi; Senussi, Ashraf (2008). Old Kingdom Pottery from Giza. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-305-986-6.

- Hayes, William (1978). The Scepter of Egypt: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, From the Earliest Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. OCLC 7427345.

- "Head and torso of a king". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David, eds. (2012). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section One, Near and Middle East. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5. ISSN 0169-9423.

- Jacquet-Gordon, Helen (1962). Les noms des domaines funéraires sous l'ancien empire égyptien. Bibliothèque d'étude (in الفرنسية). Vol. 34. Le Caire: Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale. OCLC 18402032.

- Janák, Jiří; Vymazalová, Hana; Coppens, Filip (2010). "The Fifth Dynasty 'sun temples' in a broader context". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2010. Prague: Charles University, Faculty of Arts. pp. 430–442.

- Krejčí, Jaromir (2005). "Pyramid "Lepsius no. XXIV"". Czech Institute of Egyptology. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- Krejčí, Jaromír; Arias Kytnarová, Katarína; Odler, Martin (2015). "Archaeological excavation of the mastaba of Queen Khentkaus III (Tomb AC 30)" (PDF). Prague Egyptological Studies. Czech Institute of Archaeology. XV: 28–42.

- Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3.

- Lehner, Mark (2011). "A Hundred and One Years Later: Peering into the Menkaure Valley Temple" (PDF). AERA, Working Through Change, Annual Report 2010–2011. Boston: Ancient Egypt Research Associates. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- Lehner, Mark; Jones, Daniel; Yeomans, Lisa Marie; Mahmoud, Hanan; Olchowska, Kasia (2011). "Re-examining the Khentkawes Town". In Strudwick, Nigel; Strudwick, Helen (eds.). Old Kingdom, New Perspectives: Egyptian Art and Archaeology 2750–2150 BC. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-84217-430-2.

- Lehner, Mark (2015). "Shareholders: the Menkaure valley temple occupation in context". In Der Manuelian, Peter; Schneider, Thomas (eds.). Towards a new history for the Egyptian Old Kingdom: perspectives on the pyramid age. Harvard Egyptological studies. Vol. 1. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-30189-4.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (2013). The great name: ancient Egyptian royal titulary. Writings from the ancient world, no. 33. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-736-2.

- Magdolen, Dušan (2008). "Lepsius No XXV: a problem of typology". Asian and African Studies. 17 (2): 205–223.

- Malek, Jaromir (2000a). "The Old Kingdom (c. 2160–2055 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Malek, Jaromir (2000b). "Old Kingdom rulers as "local saints" in the Memphite area during the Old Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prag: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 241–258. ISBN 80-85425-39-4.

- Mariette, Auguste (1864). "La table de Saqqarah". Revue Archéologique (in الفرنسية). Paris: Didier. 10: 168–186. OCLC 458108639.

- Mariette, Auguste (1885). Maspero, Gaston (ed.). Les mastabas de l'ancien empire : fragment du dernier ouvrage de Auguste Édouard Mariette (PDF). Paris: F. Vieweg. OCLC 722498663.

- Morales, Antonio J. (2006). "Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir. Late Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005, Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague (June 27 – July 5, 2005). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 311–341. ISBN 978-80-7308-116-4.

- Mumford, G. D. (1999). "Wadi Maghara". In Bard, Kathryn; Shubert, Steven Blake (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. New York: Routledge. pp. 875–876. ISBN 978-0-415-18589-9.

- Munro, Peter (1993). Das Unas-Friedhof Nord-West I: topographisch-historische Einleitung (in الألمانية). Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-1353-7.

- "Neuserre". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- Nolan, John (2012). "Fifth Dynasty Renaissance at Giza" (PDF). AERA Gram. Vol. 13, no. 2. Boston: Ancient Egypt Research Associates. ISSN 1944-0014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- "Niuserre BMFA catalog". Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- Nuzzolo, Massimiliano (2025). "A New Seal-Impression of King Shepseskara and the Fifth Dynasty Chronology". Ägypten und Levante. Internationale Zeitschrift für ägyptische Archäologie und deren Nachbargebiete. 34: 393–418. doi:10.1553/AEundL34s393.

- "Nyuserre on the MMA online catalog". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- "Nyuserre Ini". Digital Egypt for Universities. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- "Petrie museum, online collection". Petrie Museum. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- "Reliefs from the Shesepibre in the Petrie museum, online collection". Petrie Museum. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- Porter, Bertha; Moss, Rosalind L. B.; Burney, Ethel W. (1981). Topographical bibliography of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic texts, reliefs, and paintings. III/1. Memphis. Abû Rawâsh to Abûṣîr (PDF) (second, revised and augmented by Jaromír Málek ed.). Oxford: Griffith Institute, Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-900416-19-4.

- Porter, Bertha; Moss, Rosalind L. B.; Burney, Ethel W. (1951). Topographical bibliography of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic texts, reliefs, and paintings. VII Nubia, the deserts, and outside Egypt (PDF). Oxford: Griffith Institute, Clarendon Press. OCLC 312542797.

- Posener-Kriéger, Paule (1976). Les archives du temple funéraire de Neferirkare-Kakai (Les papyrus d'Abousir). Tomes I & II (complete set). Traduction et commentaire. Bibliothèque d'études (in الفرنسية). Vol. 65. Le Caire: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. OCLC 4515577.

- Rice, Michael (1999). Who is who in Ancient Egypt. Routledge London & New York. ISBN 978-0-203-44328-6.

- Richter, Barbara (2013). "Sed Festival Reliefs of the Old Kingdom". Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the 58th Annual Meeting of the American Research Center in Egypt, Wyndham Toledo Hotel, Toledo, Ohio, Apr 20, 2007. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- "Royal Head, Probably King Nyuserre". Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- Roth, Silke (2001). Die Königsmütter des Alten Ägypten von der Frühzeit bis zum Ende der 12. Dynastie. Ägypten und Altes Testament (in الألمانية). Vol. 46. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-04368-7.

- Ryholt, Kim (1997). The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c. 1800–1550 B.C. CNI publications, 20. Carsten Niebuhr Institute of Near Eastern Studies, University of Copenhagen : Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-87-7289-421-8.

- Schmitz, Bettina (1976). Untersuchungen zum Titel s3-njśwt "Königssohn". Habelts Dissertationsdrucke: Reihe Ägyptologie (in الألمانية). Vol. 2. Bonn: Habelt. ISBN 978-3-7749-1370-7.

- Shaw, Ian (2003). "New fieldwork at Gebel el-Asr: "Chephren's diorite quarries"". In Hawass, Zahi; Pinch Brock, Lyla (eds.). Egyptology at the Dawn of the Twenty-first Century: Archaeology. Cairo, New York: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-424-715-6.

- Smith, William Stevenson (1949). A History of Egyptian Sculpture and Painting in the Old Kingdom (second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. OCLC 558013099.

- Strouhal, Eugen; Černý, Viktor; Vyhnánek, Luboš (2000). "An X-ray examination of the mummy found in pyramid Lepsius no. XXIV at Abusir". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000 (PDF). Prag: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 543–550. ISBN 80-85425-39-4. Archived from the original on 1 February 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Strudwick, Nigel (1985). The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders (PDF). Studies in Egyptology. London; Boston: Kegan Paul International. ISBN 978-0-7103-0107-9.

- Strudwick, Nigel C. (2005). Texts from the Pyramid Age. Writings from the Ancient World (book 16). Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-680-8.

- Tallet, Pierre (2015). "Les "ports intermittents" de la mer Rouge à l'époque pharaonique : caractéristiques et chronologie". NeHeT – Revue numérique d'Égyptologie (in الفرنسية). Vol. 3.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2005). À la découverte des pyramides d'Égypte. Champollion (in الفرنسية). Translated by Nathalie Baum. Monaco: Éditions du Rocher. ISBN 978-2-268-05326-4.

- Vachala, Břetislav (1979). "Ein weiterer Beleg für die Königin Repewetnebu?". Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde (in الألمانية). Vol. 106. p. 176. ISSN 2196-713X.

- Van de Mieroop, Marc (2011). A history of ancient Egypt. Blackwell history of the ancient world. Chichester, West Sussex; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-6071-1.

- Verner, Miroslav (1976). "Czechoslovak Excavations at Abusir". Abstracts of Papers, First International Congress of Egyptology, October 2–10, 1976. Munich. pp. 671–675.

- Verner, Miroslav (1980a). "Excavations at Abusir". Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde. Vol. 107. pp. 158–169.

- Verner, Miroslav (1980b). "Die Königsmutter Chentkaus von Abusir und einige Bemerkungen zur Geschichte der 5. Dynastie". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur (in الألمانية). Vol. 8. pp. 243–268.

- Verner, Miroslav (1985). "Un roi de la Ve dynastie. Rêneferef ou Rênefer ?". Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in الفرنسية). 85: 281–284.

- Verner, Miroslav; Zemina, Milan (1994). Forgotten pharaohs, lost pyramids: Abusir (PDF). Praha: Academia Škodaexport. ISBN 978-80-200-0022-4. Archived from the original on 1 February 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Verner, Miroslav; Posener-Kriéger, Paule; Jánosi, Peter (1995). Abusir III : the pyramid complex of Khentkaus. Excavations of the Czech Institute of Egyptology. Praha: Universitas Carolina Pragensis: Academia. ISBN 978-80-200-0535-9.

- Verner, Miroslav (1997a). The Pyramids: the mystery, culture, and science of Egypt's great monuments. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3935-1.

- Verner, Miroslav (1997b). "Further thoughts on the Khentkaus problem" (PDF). Discussions in Egyptology. Vol. 38. pp. 109–117. ISSN 0268-3083.

- Verner, Miroslav (2000). "Who was Shepseskara, and when did he reign?". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000 (PDF). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 581–602. ISBN 978-80-85425-39-0. Archived from the original on 1 February 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Verner, Miroslav (2001a). "Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology" (PDF). Archiv Orientální. 69 (3): 363–418.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001b). "Old Kingdom: An Overview". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 585–591. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Verner, Miroslav (2007). "New Archaeological Discoveries in the Abusir Pyramid Field". Archaeogate. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Verner, Miroslav (2012). "Pyramid towns of Abusir". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 41: 407–410. JSTOR 41812236.

- Verner, Miroslav (2014). Sons of the Sun. Rise and decline of the Fifth Dynasty. Prague: Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Arts. ISBN 978-80-7308-541-4.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1982). "Niuserre". In Helck, Wolfgang; Otto, Eberhard (eds.). Lexikon der Ägyptologie. Band IV: Megiddo – Pyramiden (in الألمانية). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 517–518. ISBN 978-3-447-02262-0.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1997). Chronologie des pharaonischen Ägypten : die Zeitbestimmung der ägyptischen Geschichte von der Vorzeit bis 332 v. Chr. Münchner ägyptologische Studien (in الألمانية). Vol. 46. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-2310-9.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen (in الألمانية). Münchner ägyptologische Studien, Heft 49, Mainz : Philip von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-2591-2.

- Waddell, William Gillan (1971). Manetho. Loeb classical library, 350. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press; W. Heinemann. OCLC 6246102.

- Wildung, Dietrich (1969). Die Rolle ägyptischer Könige im Bewußtsein ihrer Nachwelt. Teil I. Posthume Quellen über die Könige der ersten vier Dynastien. Münchner Ägyptologische Studien (in الألمانية). Vol. 17. Berlin: Verlag Bruno Hessling. OCLC 635608696.

- Wilkinson, Toby (2000). Royal annals of ancient Egypt: the Palermo stone and its associated fragments. Studies in Egyptology. London, New York: Kegan Paul International: distributed by Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-7103-0667-8.

- Zibelius-Chen, Karola (1978). Ägyptische Siedlungen nach Texten des Alten Reiches. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients (in الألمانية). Vol. 19, Reihe B. Wiesbaden: Reichert. ISBN 978-3-88226-012-0.

- Ziegler, Christiane (2007). Le Mastaba d'Akhethetep. Fouilles du Louvre à Saqqara (in الفرنسية). Vol. 1. Paris, Louvain: Musée du Louvre, Peeters. ISBN 978-2-35031-084-8.

وصلات خارجية

| سبقه شپ سس كا رع (غالباً) أو نفر إف رع |

فرعون ح. 2458 ق.م. - ح. 2422 ق.م. |

تبعه من كاو حور |

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- مواليد الألفية الثالثة ق.م.

- وفيات القرن 25 ق.م.

- فراعنة القرن 25 ق.م.

- فراعنة الأسرة المصرية الخامسة

- تاريخ مصر القديمة