نوازل الكهوف

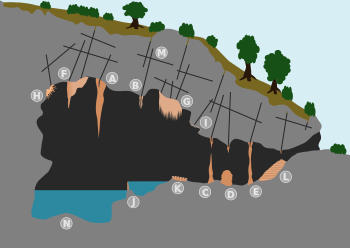

نوازل الكهوف أو متدليات الكهوف Stalactite، من (من اليونانية σταλάσσω ستالاسّو) وتعني تقاطر الماء) هي نوع من التكوينات المعدنية الطبيعية تتكوّن متدلية من أسقف الكهوف الرطبة أو المحتوية على المياه. ويعتمد لونها على نوع المعادن الخام التي تدخل في التكوين الحجري للكهف. Any material that is soluble and that can be deposited as a colloid, or is in suspension, or is capable of being melted, may form a stalactite. Stalactites may be composed of lava, minerals, mud, peat, pitch, sand, sinter, and amberat (crystallized urine of pack rats).[1][2] A stalactite is not necessarily a speleothem, though speleothems are the most common form of stalactite because of the abundance of limestone caves.[1][3]

The corresponding formation on the floor of the cave is known as a stalagmite.

تكونها وأنواعها

تتكون المتدليات الكهفية عن طريق ترسيب كربونات الكالسيوم وبعض أملاح معادن أخرى والتي تترسب من محاليل مياه معدنية. ويتكون الحجر الجيري من كربونات الكالسيوم، ويذيب الماء المتساقط في الكهف والذي يحتوي عادة على ثاني أكسيد الكربون كربونات الكالسيوم مكونا محلول بيكربونات الكالسيوم. ويمكن التعبير عن ذلك التفاعل بالمعادلة الآتية:

- (CaCO3(s) + H2O (l) + CO2 (aq) → Ca(HCO3)2 (aq

ويتسرب هذا المحلول خلال صخور الكهف هابطا حتي يصل إلى إحدى الحبيبات المعلقة في سقف الكهف ويتقاطر منها. وعندما يقابل المحلول الهواء ينعكس التفاعل الكيميائي الذي حدث من قبل وتترسب كربونات الكالسيوم عليها. والمعادلة الكيميائية الفعالة عندئذ هي:

- (Ca(HCO3)2 (aq) → CaCO3 (s) + H2O (l) + CO2 (aq

ويقدر معدل تنامي المتدلية 0.13 مليمتر في السنة. تتكون أسرع تلك المتدليات من ماء متسرب سريع مكونا محلولا مركزا من كربونات الكالسيوم وثاني أكسيد الكربون، ويمكن أن يصل معدل تناميها إلى 3 مليمتر في السنة ..[4]

ويبدأ كل متدلى بتقاطر نقطة واحدة من الماء المحمل بالأملاح المعدنية. وعندتساقط النقط فإنها تترك عالقا حلقة رقيقة من الكالسيت. وتشكل كل نقطة متساقطة أخرى حلقة أخرى من الكالسيت. وقد تأخذ بعض تلك المتدليات شكلا أنبوبيا ويسمى عندئذ أنابيب الصودا. وقد تنمو تلك االأنابيب إلى أطوالاً طويلة إلا أنها تكون هشة سهلة الكسر. فإذا ما انسدت تلك الأنابيب بالشوائب يبدأ الماء في التساقط من سطحها الخارجي. وبتتابع تساقط الماء وترسب الكالسيت ينكون الشكل المخروطي المعهود للمتدليات. وتتساقط نفس قطرات الماء من المتدلي على الأرض مكونة صواعدا مخروطية تنتصب على الأرض، ويسمى هذا الصاعد الكهفي stalagmite. وبعكس المتدليات فالصواعد الكهفية لا تبدأ تكوينها في هيئة أنبوب من الصودا. ومع الوقت قد تكبر تلك الصواعد مكونة أعمدة متراصة.

Stalactite formation generally begins over a large area, with multiple paths for the mineral rich water to flow. As minerals are dissolved in one channel slightly more than other competing channels, the dominant channel begins to draw more and more of the available water, which speeds its growth, ultimately resulting in all other channels being choked off. This is one reason why formations tend to have minimum distances from one another. The larger the formation, the greater the interformation distance.

Pillars

The same water drops that fall from the tip of a stalactite deposit more calcite on the floor below, eventually resulting in a rounded or cone-shaped stalagmite. Unlike stalactites, stalagmites never start out as hollow "soda straws". Given enough time, these formations can meet and fuse to create a speleothem of calcium carbonate known as a pillar, column, or stalagnate.[5]

Lava stalactites

Another type of stalactite is formed in lava tubes while molten and fluid lava is still active inside.[6] The mechanism of formation is the deposition of molten dripping material on the ceilings of caves, however with lava stalactites formation happens very quickly in only a matter of hours, days, or weeks, whereas limestone stalactites may take up to thousands of years. A key difference with lava stalactites is that once the lava has ceased flowing, so too will the stalactites cease to grow. This means that if the stalactite were to be broken it would never grow back.[1]

The generic term lavacicle has been applied to lava stalactites and stalagmites indiscriminately and evolved from the word icicle.[1]

Like limestone stalactites, they can leave lava drips onto the floor that turn into lava stalagmites and may eventually fuse with the corresponding stalactite to form a column.

نوازل أسنان القرش

The shark tooth stalactite is broad and tapering in appearance. It may begin as a small driblet of lava from a semi-solid ceiling, but then grows by accreting layers as successive flows of lava rise and fall in the lava tube, coating and recoating the stalactite with more material. They can vary from a few millimeters to over a meter in length.[7]

Splash stalactites

As lava flows through a tube, material will be splashed up on the ceiling and ooze back down, hardening into a stalactite. This type of formation results in an irregularly-shaped stalactite, looking somewhat like stretched taffy[مطلوب توضيح]. Often they may be of a different color than the original lava that formed the cave.[7]

Tubular lava stalactites

When the roof of a lava tube is cooling, a skin forms that traps semi-molten material inside. Trapped gases expansion forces lava to extrude out through small openings that result in hollow, tubular stalactites analogous to the soda straws formed as depositional speleothems in solution caves. The longest known is almost 2 meters in length. These are common in Hawaiian lava tubes and are often associated with a drip stalagmite that forms below as material is carried through the tubular stalactite and piles up on the floor beneath. Sometimes the tubular form collapses near the distal end, most likely when the pressure of escaping gases decreased and still-molten portions of the stalactites deflated and cooled. Often these tubular stalactites acquire a twisted, vermiform appearance as bits of lava crystallize and force the flow in different directions. These tubular lava helictites may also be influenced by air currents through a tube and point downwind.[7]

Ice stalactites

A common stalactite found seasonally or year round in many caves is the ice stalactite, commonly referred to as icicles, especially on the surface.[8] Water seepage from the surface will penetrate into a cave and if temperatures are below freezing, the water will form stalactites. They can also be formed by the freezing of water vapor.[9] Similar to lava stalactites, ice stalactites form very quickly within hours or days. Unlike lava stalactites however, they may grow back as long as water and temperatures are suitable.

Ice stalactites can also form under sea ice when saline water is introduced to ocean water. These specific stalactites are referred to as brinicles.

Ice stalactites may also form corresponding stalagmites below them and given time may grow together to form an ice column.

نوازل خرسانية

Stalactites can also form on concrete, and on plumbing where there is a slow leak and where there are calcium, magnesium or other ions in the water supply, although they form much more rapidly there than in the natural cave environment. These secondary deposits, such as stalactites, stalagmites, flowstone and others, which are derived from the lime, mortar or other calcareous material in concrete, outside of the "cave" environment, can not be classified as "speleothems" due to the definition of the term.[10] The term "calthemite" is used to encompass these secondary deposits which mimic the shapes and forms of speleothems outside the cave environment.[11]

The way stalactites form on concrete is due to different chemistry than those that form naturally in limestone caves and is due to the presence of calcium oxide in cement. Concrete is made from aggregate, sand and cement. When water is added to the mix, the calcium oxide in the cement reacts with water to form calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2). The chemical formula for this is:[12]

- CaO (s) + H 2O (l) → Ca(OH) 2 (aq)

Over time, any rainwater that penetrates cracks in set (hard) concrete will carry any free calcium hydroxide in solution to the edge of the concrete. Stalactites can form when the solution emerges on the underside of the concrete structure where it is suspended in the air, for example, on a ceiling or a beam. When the solution comes into contact with air on the underside of the concrete structure, another chemical reaction takes place. The solution reacts with carbon dioxide in the air and precipitates calcium carbonate.[12]

- Ca(OH) 2 (aq) + CO 2 (g) → CaCO 3 (s) + H 2O (l)

When this solution drops down it leaves behind particles of calcium carbonate and over time these form into a stalactite. They are normally a few centimeters long and with a diameter of approximately 4 إلى 5 mm (0.16 إلى 0.20 بوصات).[12] The growth rate of stalactites is significantly influenced by supply continuity of Ca2+ saturated solution and the drip rate. A straw shaped stalactite which has formed under a concrete structure can grow as much as 2 mm per day in length, when the drip rate is approximately 11 minutes between drops.[11] Changes in leachate solution pH can facilitate additional chemical reactions, which may also influence calthemite stalactite growth rates.[11]

أرقام قياسية

The White Chamber in the Jeita Grotto's upper cavern in Lebanon contains an 8.2 m (27 ft) limestone stalactite which is accessible to visitors and is claimed to be the longest stalactite in the world.[citation needed] Another such claim is made for a 20 m (66 ft) limestone stalactite that hangs in the Chamber of Rarities in the Gruta Rei do Mato (Sete Lagoas, Minas Gerais, Brazil).[citation needed] However, cavers have often encountered longer stalactites during their explorations. One of the longest stalactites viewable by the general public is in Pol an Ionain (Doolin Cave), County Clare, Ireland, in a karst region known as The Burren; what makes it more impressive is the fact that the stalactite is held on by a section of calcite less than 0.3 m2 (3.2 sq ft).[13]

نشأة المصطلح

Stalactites are first mentioned (though not by name) by the Roman natural historian Pliny in a text which also mentions stalagmites and columns and refers to their formation by the dripping of water. The term "stalactite" was coined in the 17th century by the Danish Physician Ole Worm,[14] who coined the word from the Greek word σταλακτός (stalaktos, "dripping") and the Greek suffix -ίτης (-ites, connected with or belonging to).[15]

انظر أيضاً

- صواعد الكهوف

- Lavacicle

- Rusticle

- كارست

- Icicle

- Bottlebrush - Stalactite coated with pool spar.

- Brinicle

معرض الصور

كهف كاريسباد، إيطاليا.

متدليات طولها 5 و6 متر في كهف دولين، إيرلندا.

أنابيب الصودا في كهف كورناش، فرنسا

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت ث Larson, Charles (1993). An Illustrated Glossary of Lava Tube Features, Bulletin 87, Western Speleological Survey. p. 56.

- ^ Hicks, Forrest L. (1950). "Formation and mineralogy of stalactites and stalagmites" (PDF). 12: 63–72. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "How Caves Form". Nova (American TV series). Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ^ Kramer, Stephen P.; Day, Kenrick L. (1995), Caves, Carolrhoda Books (published 1994), p. 23, ISBN 9780876144473

- ^ "Pillars". showcaves.com.

- ^ Baird, A.K. (1982). "Basaltic "stalactite" mineralogy and chemistry, Kilauea". 4 (4). Geological Society of America Bulletin, abstracts with programs: 146–147.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ أ ب ت Bunnell, Dave (2008). Caves of Fire: Inside America's Lava Tubes. p. 124.

- ^ Keiffer, Susan (2010). "Ice stalactite dynamics". Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- ^ Lacelle, Denis (2009). "Formation of seasonal ice bodies and associated cryogenic carbonates in Cavene De L'Ours, Que' Bec, Canada: Kinetic isotope effects and pseudo-biogenic crystal structures" (PDF). Journal of Cave and Karst Studies. pp. 48–62. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHill&Forti1986 - ^ أ ب ت Smith, G K. (2016). "Calcite straw stalactites growing from concrete structures". Cave and Karst Science 43(1), pp4-10.

- ^ أ ب ت Braund, Martin; Reiss, Jonathan (2004), Learning Science Outside the Classroom, Routledge, pp. 155–156, ISBN 0-415-32116-6

- ^ "Caves With The Longest Stalactite". Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ^ Olao Worm, Museum Wormianum. ... (Amsterdam ("Amstelodami"), (the Netherlands): Louis & Daniel Elzevier, 1655), pages 50-52.

- ^ See: Online Etymology Dictionary

- Dripstone in time-lapse ("Tropfsteine im Zeitraffer") - Schmidkonz, B.; Wittke, G.; Chemie Unserer Zeit, 2006, 40, 246. doi:10.1002/ciuz.200600370

وصلات خارجية

- The Virtual Cave's page on stalactites

- "Stalactites" by Enrique Zeleny, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.