طارق العيسمي

طارق العيسمي | |

|---|---|

Tareck El Aissami | |

| |

| نائب رئيس ڤنزويلا | |

| تولى المنصب 4 يناير 2017 | |

| الرئيس | نيكولاس مادورو |

| سبقه | أريسوبولو إستوريز |

| حاكم أراگوا | |

| في المنصب 2012–2017 | |

| سبقه | رفائيل عيسى |

| خلـَفه | Caryl Bertho |

| وزير الداخلية والعدل | |

| في المنصب سبتمبر 2008 – أكتوبر 2012 | |

| سبقه | Ramón Rodríguez Chacín |

| خلـَفه | نستور رڤرول |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | طارق زيدان العيسمي مداح 12 نوفمبر 1974 إل ڤيگيا، ميريدا، ڤنزويلا[1] |

| القومية | ڤنزويلي |

| الحزب | الحزب الاشتراكي المتحد |

| المدرسة الأم | جامعة الأنديز |

| المهنة | سياسي |

طارق زيدان العيسمي مداح[3] (و. 12 نوفمبر 1974)[4]، هو سياسي ڤنزويلي ويشغل منصب نائب رئيس ڤنزويلا منذ يناير 2017. كان في السابق وزير للداخلية والعدل من 2008 حتى 2012 وحاكم أراگوا من 2012 حتى 2017. واجه العيسمي تهم بالمشاركة في الفساد، غسيل الأموال وتجارة المخدرات، التي أنكرها كلها.[5]

حياته المبكرة

وُلد العيسمي في 12 نوفمبر 1974 في إل ڤيگيا، ميريدا، ڤنزويلا،[4][6] حيث قضى طفولته.[7] وكان لديه أربعة أشقاء. [8] والده، زيدان الأمين العيسمي، وشهرته كارلوس زيدان، كان مهاجراً درزياً من جبل الدروز في سوريا.[9] كان زعيم حزب البعث العراقي في ڤنزويلا وكان لديه علاقات بالحركات السياسية اليسارية في الشرق الأوسط.[10][11][6] كان جده الأكبر، شبلي العيسمي، منتمياً في حزب البعث، وكان يشغل منصب مساعد الأمين العام للقيادة الوطنية لحزب البعث العراقي.[10][12][13][14]

دعم والده هوگو تشاڤيز أثناء محاولة الانقلاب الڤنزويلي 1992 وتم اعتقاله.[10][11][6] في أعقاب أنباء اعتقال والده والهجوم على مسقط رأسه، أصيب طارق العيسمي الشاب ذو السبعة عشر عاماً بخيبة أمل بسبب الأوضاع المضطربة التي حلت بدولة ڤنزويلا.[15][16] بعد اعتقال والده عام 1992، تقاعد جده الأكبر شبلي العيسمي من الحياة السياسية في العراق، وظل في البلاد حتى غزوها في 2003.

التعليم

حياته السياسية

الأونيديكس

In September 2003, Hugo Cabezas, El Aissami's close friend from the ULA and Utopia, was appointed to be the head of the National Office of Identification and Foreigners (ONIDEX), a passport and naturalization agency that was part of Venezuela's interior ministry, by President Hugo Chávez.[citation needed] The same year,[17] after El Aissami had lost the student reelection campaign, Cabezas invited him to work as his deputy at ONIDEX.[6][18] Cabezas and El Aissami were then assigned to Mission Identidad, a Bolivarian mission tasked with creating national identifications for Venezuelans.

الجمعية الوطنية ووزارة الداخلية

حاكم أراگوا

نائب الرئيس

في 4 يناير 2017 عينه الرئيس نيكولاس مادورا نائباً له.[9][19] بسبب الجدل المحيط بالعيسمي، أثار تعيينه الكثير من الخلافات. إذا ما عقدت انتخابات مبكرة في 2017، سيصبح العيسمي رئيساً لڤنزويلا حتى 2019.[20]

Due to controversy surrounding El Aissami, the appointment was contentious. If the then-proposed recall election were to occur in 2017, he would have become the President of Venezuela until the end of what would have been Maduro's remaining tenure into 2019.[20]

صلاحيات الحكم بمرسوم

Jose Vicente Haro, constitutional law professor of Central University of Venezuela[21]

On 26 January 2017, President Maduro ruled by decree that El Aissami could use economic decree powers as well, granting El Aissami powers that a Vice-President in Venezuela had not held before and power that rivaled Maduro's own powers. El Aissami was granted the power to decree over "everything from taxes to foreign currency allotments for state-owned companies" as well as "hiring practices to state-owned enterprises". The move made El Aissami one of the most powerful men in Venezuela.[21]

وزير الصناعة والانتاج الوطني

In June 2018, El Aissami was named the Minister of Industry and National Production, being tasked with overseeing Venezuela's domestic production.[22]

While serving in the ministry, El Aissami was also named as an External Director of Venezuela's state-run oil company, PDVSA.[23]

وزير البترول

In April 2020, he was named the Minister of Petroleum. His appointment marks a blow to an era of military control at Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA).[24]

On 29 November 2022, Petroleum Minister Tarek El Aissami met in Caracas with the president of Chevron Corporation, Javier La Rosa. The Venezuelan ruling party says it is committed to "the development of oil production" after the easing of sanctions. The most important joint ventures where Chevron is involved in Venezuela are Petroboscán, in the west of the nation, and Petropiar, in the eastern Orinoco Belt, with a production capacity of close to 180,000 barrels per day between both projects. In the case of Petroboscán, current production is nil and, in Petropiar, current records indicate close to 50,000 barrels per day.[25]

Al Aissami resigned from his position on Monday 20 March 2023 via Twitter, with his resignation accepted by Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. Al Aissami has been accused of corruption and financial mismanagement.[26] He was arrested by the Venezuelan prosecutor's office on charges of treason, money laundering and criminal association.[27] He was replaced in his role as Minister by Pedro Rafael Tellechea. [28]

جدل

اتهامات تجارة المخدرات وغسيل الأموال

شبكة الإرهاب

العقوبات

El Aissami has been sanctioned by several countries.

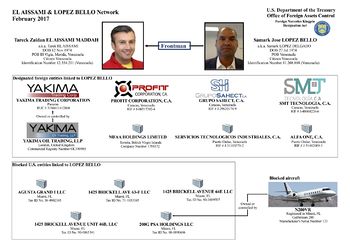

The United States Treasury Department sanctioned El Aissami on 13 February 2017 under the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act after being accused of facilitating drug shipments from Venezuela to Mexico and the United States, freezing tens of millions of dollars of assets purportedly under El Aissami's control.[30][31][32]

Canada sanctioned El Aissami on 22 September 2017 due to rupture of Venezuela's constitutional order following the 2017 Venezuelan Constituent Assembly election.[33][34]

The European Union sanctioned El Aissami on 25 June 2018, with his assets frozen and being banned from travel. The European Union stated that when El Aissami was Vice President of Venezuela, the SEBIN intelligence service, under his command, made him "responsible for the serious human rights violations carried out by the organization, including arbitrary detention, politically motivated investigations, inhumane and degrading treatment, and torture".[35]

Switzerland sanctioned El Aissami on 10 July 2018, freezing his assets and imposing a travel ban while citing the same reasons of the European Union.[36][37][38]

حياته الشخصية

طارق متزوج من ريادة رودي عامر، وهي ڤنزويلية ذات أصول سورية درزية أيضاً، وأنجب منها ابنين هما أليخاندرو، وسباستيان.

El Aissami and his father both showed support for the government of Saddam Hussein following the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003. His father, Zaidan, wrote the article "Proud to be a Taliban", describing United States President George W. Bush as "genocidal, mentally deranged, a liar and a racist" while also describing the leader of Al-Qaeda as "the great Mujahedeen, Sheik Osama bin Laden". Zaidan El Aissami also alleged that the United States may have been responsible for the 11 September terrorist attacks to create an excuse to invade Afghanistan.[14]

On 4 February 2015, it was revealed that Aragua FC had signed him as a striker.[39] Aragua FC was heavily sponsored from El Aissami's state and there are no records of him receiving playing time on the field as of January 2017.[40]

Prior to his participation in dialogue between the opposition and Venezuelan government as well as his appointment to the vice presidency, members of El Aissami's family, including his father and mother, traveled to stay in the United States for unknown reasons in late October 2016.[41]

During the pandemic in Venezuela, El Aissami tested positive for COVID-19 on 10 July 2020.[42]

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ "¿Quién es Tareck El Aissami, el nuevo vicepresidente de Venezuela?" (in Spanish). Telesur (4 January 2017). Retrieved on 5 January 2017.

- ^ الوزير طارق العيسمي نائبا لرئيس جمهورية فنزويلا [The minister Tariq Aisami vice-president of the Republic of Venezuela]. Al Amama. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|script-title=: missing prefix (help) - ^ سوري الأصل من السويداء يصبح حاكم ولاية بفنزويلا [Syrian with As-Suwayda origins become a state governor in Venezuela]. Panet. 17 ديسمبر 2012. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|script-title=: missing prefix (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب "Biografía: Tareck El Aissami" (in الإسبانية). United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). Archived from the original on 28 January 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Press, Associated (2017-02-13). "US accuses Venezuelan vice-president of role in global drug trafficking". The Guardian (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Rosati, Andrew; Zero, Fabiola (6 February 2017). "Venezuela's New Iron-Fisted Boss Facing U.S. Trafficking Probe". Bloomberg. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ Ral, Dahir (24 May 2012). "Tareck El Aisamí: Los hombres capaces son los que escriben la historia". Venezolana de Televisión. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) (Archive) - ^ "Venezuela president names new potential successor". The Guardian. Manchester, England. Agence France-Presse (AFP). 5 January 2017. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب Mary Anastasia O'Grady, "The Iran-Cuba-Venezuela Nexus: The West underestimates the growing threat from radical Islam in the Americas", The Wall Street Journal, November 23, 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت Brownfield, William (26 January 2007). CHAVEZ'S NEW CABINET: A LOOK AT SOME NEW MINISTERS. Embassy of the United States, Caracas. pp. 1–4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check|first1=value (help) - ^ أ ب "Tareck El Aissami, el político chavista compañero de Diosdado en el Cartel de los Soles". Diario Las Americas. 29 January 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Perdue, Jon B. (2012). The War of All the People: The Nexus of Latin American Radicalism and Middle Eastern Terrorism (1st ed.). Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books. pp. 160–162. ISBN 1597977047. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ "Revelan detalles del polémico perfil de Tareck El Aissami". Diario Las Américas (in الإسبانية). 11 February 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ أ ب Gunson, Phil; Adams, David (28 November 2003). "Venezuela Shifts Control of Border". St.Petersburg Times.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Luchas estudiantiles de izquierda marcan trayectoría política de El Aissami". Agencia Venezolana de Noticias (in الإسبانية). 12 October 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ^ Ral, Dahir. "Tareck El Aissami, Los hombres capaces son los que escriben la historia…". Venezolana de Televisión. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ^ "Los nexos de Hezbollah en América Latina Hezbollah, Hezbollah en Latinoamérica, Terrorismo, Irán en América Latina, Irán en Latinoamérica, Venezuela, FARC, Los Zetas, Cártel de Sinaloa - América". Infobae. 22 May 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ Morgenthau, Robert M. (8 September 2009). "Morgenthau: The Link Between Iran and Venezuela – A Crisis in the Making?". Latin American Herald Tribune. Retrieved 5 January 2017.[dead link]

- ^ "Venezuela names economy czar, oil minister in cabinet shuffle", Reuters, 4 January 2017.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMHvp - ^ أ ب "Maduro Hands Wide-Ranging Powers to Venezuela's Vice President". Bloomberg. 30 January 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ "Venezuela: President Nicolas Maduro replaces vice president, promises 'new start' | DW | 15.06.2018". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ "La experiencia brilla por su ausencia en la nueva Junta Directiva de Pdvsa (Gaceta Extraordinaria) - LaPatilla.com". LaPatilla.com (in الإسبانية الأوروبية). 2018-09-08. Retrieved 2018-09-08.

- ^ "Venezuela appoints alleged drug trafficker El Aissami as oil minister". Reuters. 2020-04-27. Retrieved 2018-04-28.

- ^ ""Now to produce!": Maduro's government announces agreements with Chevron to resume operations". 29 November 2022.

- ^ "Venezuela oil czar in surprise resignation amid graft probes". AP News. 2023-03-21. Retrieved 2023-03-21.

- ^ "Former Venezuelan oil minister is arrested in connection with corruption probe, authorities say". apnews.com. 2024-04-10. Retrieved 2024-04-10.

- ^ Buitrago, Deisy. "Venezuela president names PDVSA head Tellechea as new oil minister". Reuters. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "El Aissami Lopez Bello Network" (PDF). United States Department of Treasury. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:0 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:1 - ^ "U.S. Treasury Sanctions Venezuelan Vice President Over Drug Trade Allegations". Retrieved 2024-07-05.

- ^ "Venezuela sanctions". Government of Canada (in الإنجليزية). 22 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ "Canada sanctions 40 Venezuelans with links to political, economic crisis". The Globe and Mail. 22 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ "European Union hits 11 more Venezuelans with sanctions". The Miami Herald (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- ^ "Switzerland Sanctions 11 More Venezuelans, including Delcy Rodriguez, El Aissami, Chourio". Latin American Herald Tribune. 9 July 2018. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ "Sanctions suisses contre la vice-présidente du Venezuela" [Swiss sanctions against the vice president of Venezuela] (in الفرنسية). Swiss Broadcasting Company. 10 July 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ "Sanctions suisses contre la vice-présidente du Venezuela". Government of Switzerland (in الفرنسية). Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- ^ "Aragua anunció oficialmente a Tareck El Aissami como nuevo fichaje para el Clausura" (in الإسبانية). 4 February 2015. Archived from the original on 1 August 2015.

- ^ "Tareck El Aissami, el chavista más rechazado por la oposición". El País (in الإسبانية). 5 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ "Tension Grows Between Administration and Congress". Stratfor. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ "Venezuela oil minister El Aissami tests positive for COVID-19". Reuters. 10 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

| مناصب سياسية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه أريستوبولو إستوريز |

نائب رئيس ڤنزويلا 2017-2018 |

تبعه دلسي رودريگز |

| سبقه رفائيل إيسا |

حاكم أراگوا 2012-2017 |

تبعه كاريل برثو |

| سبقه Ramón Rodríguez Chacín |

وزير الداخلية والعدل 2008–2012 |

تبعه نستور رڤرول |

- CS1 errors: script parameters

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- CS1 errors: access-date without URL

- Articles with dead external links from July 2025

- CS1 الإسبانية الأوروبية-language sources (es-es)

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- مواليد 12 نوفمبر

- مواليد 1974

- شهر الميلاد مختلف في ويكي بيانات

- يوم الميلاد مختلف في ويكي بيانات

- Pages using infobox officeholder with unknown parameters

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2023

- Pages with empty portal template

- أشخاص أحياء

- دروز فنزويليون

- فنزويليون من أصل درزي

- فنزويليون من أصل لبناني

- فنزويليون من أصل سوري

- وزراء داخلية ڤنزويلا

- أعضاء الجمعية الوطنية (ڤنزويلا)

- سياسيو الحزب الاشتراكي المتحدة، ڤنزويلا

- حكام أراگوا

- أشخاص من ميريدا (ولاية)

- People of the Crisis in Venezuela

- Vice Presidents of Venezuela

- Fugitives wanted by the United States