اقتصاد إسپانيا

| |

| العملة | Euro (EUR, €) |

|---|---|

| 1 euro = 166.386 Spanish peseta | |

| Calendar year | |

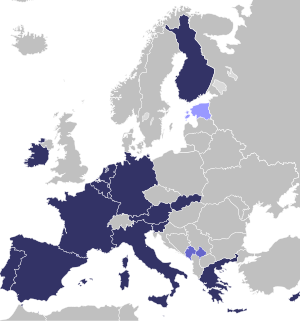

منظمات التجارة | الاتحاد الاوروپي، منظمة التجارة العالمية ومنظمة التعاون والتنمية الاقتصادية |

| احصائيات | |

| السكان | ▲ 49,077,984 (1 January 2025)[1] |

| ن.م.إ | |

| ترتيب ن.م.إ | |

نمو ن.م.إ | |

ن.م.إ للفرد | |

ن.م.إ للفرد |

|

| ▲ 3% (February 2025)[5] | |

السكان تحت خط الفقر |

|

| ▼ 31.2 medium (2024)[7] | |

القوة العاملة | |

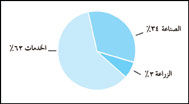

القوة العاملة حسب المهنة |

|

| البطالة | |

متوسط الراتب الإجمالي | €2,520 / $2,727 per month (2023) |

| €1,964 / $2,125 per month (2023) | |

الصناعات الرئيسية | [13][14] |

| الخارجي | |

| الصادرات | ▲ $616 billion (2023 est.)[16] |

السلع التصديرية | Machinery, motor vehicles; foodstuffs, pharmaceuticals, medicines, other consumer goods |

شركاء التصدير الرئيسيين | |

| الواردات | ▲ $552 billion (2023 est.)[16] |

السلعة المستوردة | Fuels, chemicals, semi-finished goods, foodstuffs, consumer goods, machinery and equipment, measuring and medical control instruments |

شركاء الاستيراد الرئيسيين | |

رصيد ا.أ.م | |

| المالية العامة | |

| العوائد | 41.9% of GDP (2023)[21] |

| النفقات | 45.4% of GDP (2023)[21] |

| المعونات الاقتصادية |

|

احتياطيات العملات الأجنبية | ▲ $103 billion (2023 est.)[16] |

كل القيم، ما لم يُذكر غير ذلك، هي بالدولار الأمريكي. | |

الاقتصاد الإسباني تحول من اقتصاد يعتمد بالدرجة الأولى على الزراعة إلى اقتصاد متنوع ذو أهمية في أوروبا خلال العقود الأخيرة. دخل الفرد مقارنة مع الناتج الاجمالي للدولة هو رابع أعلى دخل في أوروبا. ساهم الاتحاد الأوروبي، منذ دخول إسبانيا الاتحاد عام 1986، في تنمية الاقتصاد بشكل كبير. أهم الصناعات هي المنسوجات والمواد الغذائية والمعدنية والكيميائية والسيارات والسياحة. فرنسا و ألمانيا هم أكبر الشركاء التجاريين. أهم المنتجات الزراعية هي الشعير والخضروات والفاكهة والزيتون والعنب والشمندر السكري والحمضيات. تملك البلاد ثروة حيوانية و سمكية ضخمة.

economy of Spain is a highly developed social market economy.[28] It is the world's 14th largest by nominal GDP and the sixth-largest in Europe. Spain is a member of the European Union and the eurozone, as well as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development and the World Trade Organization. In 2023, Spain was the 18th-largest exporter in the world. Meanwhile, in 2022, Spain was the 15th-largest importer in the world. Spain is listed 27th in the United Nations Human Development Index and 29th in GDP per capita by the International Monetary Fund. Some main areas of economic activity are the automotive industry, medical technology, chemicals, shipbuilding, tourism and the textile industry. Among OECD members, Spain has a highly efficient and strong social security system, which comprises roughly 23% of GDP.[29][30][31]

During the Great Recession, Spain's economy was also in a recession. Compared to the EU and US averages, the Spanish economy entered recession later, but stayed there longer. The boom of the 2000s was reversed, leaving over a quarter of Spain's workforce unemployed by 2012. In aggregate, GDP contracted almost 9% during 2009–2013.[32] In 2012, the government officially requested a credit from the European Stability Mechanism to restructure its banking sector in the face of the crisis.[33] The ESM approved assistance and Spain drew €41 billion. The ESM programme for Spain ended with the full repayment of the credit drawn 18 months later.[34]

The economic situation started improving by 2013. By then, Spain managed to reverse the record trade deficit which had built up during the boom years.[35] It attained a trade surplus in 2013, after three decades of running a deficit.[35][36] In 2015, GDP grew by 3.2%: a rate not seen since 2007.[37][38] In 2014–2015, the economy recovered 85% of the GDP lost during the 2009–2013 recession.[39] This success led some analysts to refer to Spain's recovery as "the showcase for structural reform efforts".[40] Spain's unemployment fell substantially from 2013 to 2017. Real unemployment is much lower, as millions work in the grey market, people who count as unemployed yet perform jobs.[41] Real Spanish GDP may be around 20% bigger, as it is assumed the underground economy is annually 190 billion euros (US$224 billion).[42] Among high income European countries, only Italy and Greece are believed to have larger underground economies. Thus Spain may have higher purchasing power as well as a smaller gini coefficient[43] (inequality measure), than shown in official numbers.

The 2020 pandemic hit the Spanish economy with more intensity than other countries, as foreign tourism accounts for 5% of GDP. In the first quarter of 2023, it had fully recovered from the downturn, its GDP reaching pre-pandemic levels.[44] In 2023, Spain's economy grew 2.5%, bucking a downturn in the eurozone as a whole,[45] and is expected to grow at 3.1% in 2024, and 2.5% in 2025.[46]

التاريخ

During the first decades of the twentieth century, Spain experienced an accelerated growth of its industrial labor force and urban population; the economy became less agrarian as the process of urbanization spread after 1910. The largest sector was still agriculture but saw declines, along with fishery, relative to the share of active population engaged in the activity. The fastest growing sector at that time was services.[47]

When Spain joined the EEC in 1986 its GDP per capita was about 72% of the average of its members.[48]

At the second half of the 1990s, the conservative government of former prime minister Jose María Aznar had worked successfully to gain admission to the group of countries joining the euro in 1999. By the mid-1990s the economy had commenced the growth that had been disrupted by the global recession of the early 1990s. The strong economic growth helped the government to reduce the government debt as a percentage of GDP and Spain's high unemployment rate began to steadily decline. With the government budget in balance and inflation under control Spain was admitted into the eurozone in 1999. By 2007, Spain had achieved a GDP per capita of 105% of European Union's average due to its own economic development and the EU enlargements to 28 members, which placed it slightly ahead of Italy (103%). Three regions were included in the leading EU group exceeding 125% of the GDP per capita average level: the Basque Country, Madrid, and Navarre.[49] According to calculations by the German newspaper Die Welt in 2008, Spain's economy had been on course to overtake countries like Germany in per capita income by 2011.[50] in October 2006, Unemployment stood at 7.6% which compared favorably to many other European countries, and especially with the early 1990s when it stood at over 20%. In the past, Spain's economy had included high inflation[51] and it has always had a large underground economy.[52]

The turn to growth during the 1997-2007 period produced a real estate bubble fed by historically low interest rates, massive rates of foreign investment (during that period Spain had become a favorite of other European investment banks) and an immense surge in immigration. At its peak in 2007, construction had expanded to 15% of the total gross domestic product (GDP) of the country and 12% of total employment. During that time Spain capital inflows –including short term speculative investment– financed a large trade deficit.[48]

The downside of the real estate boom was a corresponding rise in the levels of private debt, both of households and of businesses; as prospective homeowners had struggled to meet asking prices, the average level of household debt tripled in less than a decade. This placed especially great pressure upon lower to middle income groups; by 2005 the median ratio of indebtedness to income had grown to 125%, due primarily to expensive boom time mortgages that now often exceed the value of the property.[53]

Noticeable progress continued until early 2008, when the 2007–2008 financial crisis burst Spain's property bubble.[54]

A European Commission forecast had predicted Spain would enter the world's late 2000s recession by the end of 2008.[55] At the time, Spain's Economy Minister was quoted saying, "Spain is facing its deepest recession in half a century".[56] Spain's government forecast the unemployment rate would rise to 16% in 2009. The ESADE business school predicted 20%.[57] By 2017, Spain's GDP per capita had fallen back to 95% of the European Union's average.[48]

الأزمة المالية الإسبانية 2008–2014

Like most economies, Spain's economy had been steadily growing, regardless of political changes e.g. when the ruling party changed in 2004. It maintained robust growth during the first term of prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, even though problems were becoming evident. According to the Financial Times, Spain's rapidly growing trade deficit had reached 10% of GDP by summer 2008,[58] the "loss of competitiveness against its main trading partners" and as a part of the latter, inflation which had been traditionally higher than its European competitors. This was especially affected by house price increases of 150% from 1998 and growing private sector indebtedness (115%), chiefly related to the Spanish Real Estate boom and rocketing oil prices.[59]

In April 2008, the Spanish government growth forecast was 2.3%, but this was revised down by the Ministry of Economy to 1.6%.[60] Studies by independent forecasters estimated it had actually dropped to 0.8%,[61] below the strong 3% plus growth rates during 1997–2007. During Q3 of 2008 the GDP contracted for the first time in 15 years. In February 2009, it was confirmed that Spain, along other European economies, had entered recession.[62]

In July 2009, the IMF worsened the estimates for Spain's 2009 contraction, to -4% of GDP, close to the European average of -4.6%. It estimated a further 0.8% contraction for Spain, in 2010.[63] In 2011, the deficit reached a high of 8.5%. For 2016 the deficit objective of the government was around 4%, falling to 3% for 2017. The European Commission demanded 4% for 2016 and 2.5% for 2017.[64]

Property boom and bust, 2003–2014

The adoption of the euro in 2002 had driven down long-term interest rates, prompting a surge in mortgage lending that jumped fourfold from 2000 to its 2010 apex.[65] The growth in the property market, which had begun in 1997, accelerated and within a few years had developed into a property bubble. It was financed largely by "Cajas", which are regional savings banks under the oversight of regional governments, and was fed by the historically low interest rates and a massive growth of immigration. Fueling this trend, the economy was being credited for having avoided the almost zero of some of its largest partners in the EU, in the months previous to the global Great Recession.[66]

Over the five years ending 2005, Spain's economy had created more than half of all new jobs in the EU.[67][68] At the top of its property boom, Spain was building more houses than Germany, France and the UK combined.[65] Home prices soared by 71% between 2003 and 2008, in tandem with the credit explosion.[65]

The bubble imploded in 2008, causing the collapse of Spain's large property related and construction sectors, causing mass layoffs, and a collapsing domestic demand for goods and services. Unemployment shot up. At first, Spain's banks and financial services avoided the early crisis of their international counterparts. However, as the recession deepened and property prices slid, the growing bad debts of the smaller regional savings banks, forced the intervention of Spain's central bank and government through a stabilization and consolidation program, taking over or consolidating regional "cajas", and finally receiving a bank bailout from the European Central Bank in 2012, aimed specifically for the banking business and "cajas" in particular.[69][70][71] Following the 2008 peak, home prices plunged by 31%, before bottoming out in late 2014.[65]

أزمة ديون اليورو 2010-2012

In the first weeks of 2010, renewed anxiety about excessive debt in some EU countries and, more generally, about the health of the euro spread from Ireland and Greece to Portugal, and to a lesser extent Spain. Many economists recommended a battery of policies to control the surging public debt caused by the recessionary collapse of tax revenues, combining drastic austerity measures with higher taxes. Some German policymakers went as far as to say that bailouts should include harsh penalties to EU aid recipients, such as Greece.[72] The Spanish government budget was in surplus in the years immediately before the Great Recession, and its debt was not considered excessive.

At the beginning of 2010, Spain's public debt as a percentage of GDP was still less than those of Britain, France or Germany. However, commentators pointed out that Spain's recovery was fragile, that the public debt was growing quickly, troubled regional banks may need large bailouts, growth prospects were poor and therefore limiting revenue, and that the central government had limited control over the spending of the regional governments. Under the structure of shared governmental responsibilities that has evolved since 1975, much responsibility for spending had been given back to the regions. The central government found itself in the position of trying to gain support for unpopular spending cuts from the recalcitrant regional governments.[73] In May 2010, the government announced further austerity measures, consolidating the ambitious plans announced in January.[74]

As of September 2011, Spanish banks held a record high of €142 billion of Spanish national bonds. Till Q2 2012, Spanish banks were allowed to report real estate related assets in higher non-market price by regulators. Investors who bought into such banks must be aware. Spanish houses cannot be sold at land book value after being vacant over a period of years.[بحاجة لمصدر]

أزمة التوظيف

After having completed large improvements over the second half of the 1990s and during the 2000s, Spain attained in 2007 its record low unemployment rate, at about 8%,[76] with some regions on the brink of full employment. Then Spain suffered a severe setback from October 2008, when it saw its unemployment rate surge. Between October 2007 – October 2008 the surge exceeded that of past economic crises, including 1993. In particular, during October 2008, Spain suffered its worst unemployment rise ever recorded.[77][78] Even though the sheer size of Spain's underground economy masked the real situation, employment has been a long term weakness of the economy. By 2014 the structural unemployment rate was estimated at 18%.[79] By July 2009, Spain had shed 1.2 million jobs in one year.[80] The oversized building and housing related industries were contributing greatly to the rising unemployment.[75] From 2009 thousands of established immigrants began to leave, although some did maintain residency due to poor conditions in their country of origin.[81] In all, by early 2013 Spain reached an unprecedented unemployment record at about 27%.[76]

In 2012 a radical labor reform made for a more flexible labor market, facilitating layoffs with a view to enhancing business confidence.[82]

الشباب

During the early 1990s, Spain experienced economic crisis as a result of a Europe-wide economic episode that led to a rise in unemployment. Many young adults found themselves trapped in a cycle of temporary jobs, which resulted in the creation of a secondary class of workers through reduced wages, job stability and advancement opportunities.[83] As a result, many Spaniards, predominantly unmarried young adults, emigrated to pursue job opportunities and raise their quality of life,[84] which left only a small amount of young adults living below the poverty line.[85] Spain experienced another economic crisis during the 2000s, which also prompted a rise in emigration to neighboring countries with more job stability and better economic standing.[86]

Youth unemployment remains a concern, prompting suggestions of labor market programs and job-search assistance like matching youth skills with businesses. This would improve Spain's weakened youth labor market, and their school to work transition, as young people have found it difficult to find long-term employment.[87] As of January 2025, the youth unemployment in Spain stands at 24.9%.[12]

تعافي التوظيف

The labor market reform started a trend of setting successive positive employment records. By Q2 of 2014, the economy had reversed its negative trend and started creating jobs for the first time since 2008.[82] The second quarter reversal had been extraordinary; jobs created set an absolute positive record since such quarterly employment statistics began in 1964.[88] Labor reform did seem to play an important role; one piece of evidence cited was that Spain had started creating jobs at lower rates of GDP growth than before: in previous cycles, employment rose when growth hit 2%, this time the gain came during a year when GDP had expanded by just 1.2%.[79]

Greater than expected GDP growth paved the way for further decline in unemployment. Since 2014, Spain registered steady annual falls in the official jobless figure. During 2016, unemployment experienced the steepest fall on record.[89] By the end of 2016, Spain had recovered 1.7m of the more than 3.5m jobs lost over the recession.[89] By Q4 2016 Spanish unemployment had fallen to 19%, the lowest rate in seven years.[90] In April 2017 the country recorded its biggest drop in jobless claimants for a single month to date.[91][92] In Q2 of 2017, unemployment fell to 17%, below 4 million for the first time since 2008,[93] with the country experiencing its steepest quarterly decline in unemployment on record.[94] In 2018, at 14.6% the unemployment rate did not exceed the 15% threshold for the first time since 2008 when the crisis began.[95]

As of 2017, trade unions, left, and center-left parties continued to criticize and wanted labor reform to be revoked, on grounds that it tilted the balance of power too far towards employers.[89] Most new contracts were temporary.[92] In 2019, Pedro Sánchez's socialist government increased the minimum wage by 22% in an attempt to boost hiring and encourage spending, and increased it further in the labor reform adopted at the end of 2021. Members of the opposition argued this increase, would negatively affect 1.2 million workers due to employers being unable to cover the raise, resulting in higher unemployment.[96] Contrary to such opinion, the reforms approved by Sanchez's government resulted in a robust shift towards permanent employment contracts, and led to a 15-year low in unemployment rates at 11.60%.[97]

خفض أموال الاتحاد الأوروبي

Capital contributions from the EU, which had contributed significantly to the economic empowerment of Spain since joining the EEC, have decreased considerably since 1990, due to the effects of the EU's enlargement. Agricultural funds from the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union (CAP) are now spread across more countries. And, with 2004 and 2007's enlargement of the European Union, less developed countries joined, lowering average income, so that Spanish regions which had been relatively less developed, were now at the European average or even above it. Spain has gradually become a net contributor of funds for less developed countries of the Union, as opposed to receiving funds.[98]

التعافي الاقتصادي (2014–2020)

During the economic downturn, Spain significantly reduced imports, increased exports and attracted growing numbers of tourists; as a result, after three decades of running a trade deficit the country attained in 2013 a trade surplus[35] which strengthened during 2014–15.[36]

With a 3.2% increase in 2015, growth was the highest among larger EU economies.[38] In two years (2014–2015) the economy had recovered 85% of the GDP lost during the 2009-2013 recession,[39] which had some international analysts referring to Spain's recovery as "the showcase for structural reform efforts".[40] The Spanish economy outperformed expectations and grew 3.2% in 2016, faster than the eurozone average.[99][89] One of the main drivers of recovery was international trade, in turn sparked by dramatic gains in labor productivity.[100] Exports shot up, from around 25% (2008) to 33% of GDP (2016) on the back of an internal devaluation (the country's wage bill halved in 2008–2016), a search for new markets, and a mild recovery of the European economy.[99] In the second quarter of 2017 Spain had recovered all the GDP lost during the economic crisis, exceeding for the first time output in 2008.[100]

By 2017, following several months of prices increasing, homeowners who had been renting during the economic slump had started to put their properties back on the market.[101] In this regard, home sales are expected to return in 2017 to pre-crisis (2008) level.[102] The Spanish real estate market was experiencing a new boom, this time in the rental sector.[101] Out of 50 provinces and compared to May 2007, the National Statistics Institute recorded higher rent levels in 48 provinces, with the 10 most populated accumulating rent inflation between 5% and 15% since 2007.[101] The phenomenon was most visible in big cities such as Barcelona or Madrid, which saw new record average prices, partially fueled by short-term rentals to tourists.[101]

بيانات

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2023 (plus IMF estimates for 2024–2027 in italics). Inflation below 5% is in green.[103]

| Year | GDP (in bn. US$ PPP) |

GDP per capita (in US$ PPP) |

GDP (in bn. US$ nominal) |

GDP per capita (in US$ nominal) |

GDP growth (real) |

Inflation rate (in Percent) |

Unemployment (in Percent) |

Government debt (in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 294.4 | 7,819.0 | 230.8 | 6,128.0 | ▲1.2% | ▲15.6% | 11.0% | 16.6% |

| 1981 | ▲321.0 | ▲8,443.6 | ▲13.8% | ▲20.0% | ||||

| 1982 | ▲345.0 | ▲9,028.1 | ▲1.2% | ▲15.8% | ▲25.1% | |||

| 1983 | ▲364.5 | ▲9,492.1 | ▲1.7% | ▲17.2% | ▲30.4% | |||

| 1984 | ▲384.0 | ▲9,962.0 | ▲1.7% | ▲19.9% | ▲37.1% | |||

| 1985 | ▲405.5 | ▲10,482.7 | ▲181.6 | ▲4,694.8 | ▲2.4% | ▲21.3% | ▲42.1% | |

| 1986 | ▲427.9 | ▲11,028.9 | ▲251.3 | ▲6,477.3 | ▲3.4% | ▲8.8% | ▼20.9% | ▲43.3% |

| 1987 | ▲463.5 | ▲11,919.1 | ▲318.4 | ▲8,187.3 | ▲5.7% | ▼20.2% | ▼43.1% | |

| 1988 | ▲505.2 | ▲12,963.9 | ▲374.1 | ▲9,598.7 | ▲5.3% | ▼4.8% | ▼19.2% | ▼39.6% |

| 1989 | ▲551.3 | ▲14,118.3 | ▲412.6 | ▲10,566.1 | ▲5.0% | ▲6.8% | ▼17.2% | ▲41.0% |

| 1990 | ▲593.9 | ▲15,183.5 | ▲535.7 | ▲13,693.6 | ▲3.8% | ▼16.2% | ▲42.5% | |

| 1991 | ▲629.5 | ▲16,050.8 | ▲576.4 | ▲14,697.5 | ▲2.5% | ▲16.3% | ▲43.1% | |

| 1992 | ▲649.3 | ▲16,501.7 | ▲630.1 | ▲16,013.2 | ▲0.9% | ▲7.1% | ▲18.4% | ▲45.4% |

| 1993 | ▲656.0 | ▲16,619.1 | ▼4.6% | ▲22.6% | ▲56.2% | |||

| 1994 | ▲685.7 | ▲17,323.7 | ▲531.1 | ▲13,419.6 | ▲2.3% | ▲4.7% | ▲24.1% | ▲58.7% |

| 1995 | ▲728.9 | ▲18,373.0 | ▲613.9 | ▲15,475.6 | ▲4.1% | ▼22.9% | ▲63.4% | |

| 1996 | ▲760.2 | ▲19,118.2 | ▲640.0 | ▲16,095.8 | ▲2.4% | ▼3.6% | ▼22.1% | ▲67.5% |

| 1997 | ▲803.2 | ▲20,146.4 | ▲3.9% | ▼1.9% | ▼20.6% | ▼66.2% | ||

| 1998 | ▲848.5 | ▲21,209.3 | ▲618.4 | ▲15,457.1 | ▲4.5% | ▼1.8% | ▼18.6% | ▼64.2% |

| 1999 | ▲901.3 | ▲22,413.0 | ▲636.0 | ▲15,814.2 | ▲4.7% | ▲2.2% | ▼15.6% | ▼62.5% |

| 2000 | ▲968.3 | ▲23,877.4 | ▲5.1% | ▲3.5% | ▼13.9% | ▼57.8% | ||

| 2001 | ▲1,029.1 | ▲25,244.7 | ▲627.8 | ▲15,400.9 | ▲3.9% | ▲3.6% | ▼10.5% | ▼54.1% |

| 2002 | ▲1,073.7 | ▲25,919.4 | ▲708.3 | ▲17,097.9 | ▲2.7% | ▼3.1% | ▲11.5% | ▼51.3% |

| 2003 | ▲1,127.5 | ▲26,721.1 | ▲907.3 | ▲21,501.1 | ▲3.0% | ▼3.0% | ▲11.5% | ▼47.7% |

| 2004 | ▲1,193.9 | ▲27,856.3 | ▲1,068.6 | ▲24,932.1 | ▲3.1% | ▼11.0% | ▼45.4% | |

| 2005 | ▲1,276.4 | ▲29,232.4 | ▲1,154.4 | ▲26,438.0 | ▲3.7% | ▲3.4% | ▼9.2% | ▼42.4% |

| 2006 | ▲1,369.7 | ▲30,877.5 | ▲1,260.5 | ▲28,414.1 | ▲4.1% | ▲3.5% | ▼8.5% | ▼39.1% |

| 2007 | ▲1,457.4 | ▲32,218.4 | ▲1,474.2 | ▲32,588.6 | ▲3.6% | ▼2.8% | ▼8.2% | ▼35.8% |

| 2008 | ▲1,498.6 | ▲32,589.8 | ▲1,631.7 | ▲35,484.4 | ▲0.9% | ▲4.1% | ▲11.2% | ▲39.7% |

| 2009 | ▼-0.3% | ▲17.9% | ▲53.3% | |||||

| 2010 | ▲1,471.3 | ▲31,597.3 | ▲0.2% | ▲1.8% | ▲19.9% | ▲60.5% | ||

| 2011 | ▲1,489.6 | ▲31,872.4 | ▲1,480.5 | ▲31,676.7 | ▲3.2% | ▲21.4% | ▲69.9% | |

| 2012 | ▼2.4% | ▲24.8% | ▲90.0% | |||||

| 2013 | ▲1,512.1 | ▲32,452.7 | ▲1,355.2 | ▲29,085.0 | ▼1.4% | ▲26.1% | ▲100.5% | |

| 2014 | ▲1,558.3 | ▲33,544.4 | ▲1,371.6 | ▲29,524.8 | ▲1.4% | ▼-0.2% | ▼24.4% | ▲105.1% |

| 2015 | ▲1,621.5 | ▲34,938.6 | ▲3.8% | ▼-0.5% | ▼22.1% | ▼103.3% | ||

| 2016 | ▲1,733.0 | ▲37,309.9 | ▲1,232.6 | ▲26,535.5 | ▲3.0% | ▲-0.2% | ▼19.6% | ▼102.8% |

| 2017 | ▲1,843.9 | ▲39,626.5 | ▲1,312.1 | ▲28,196.8 | ▲3.0% | ▲2.0% | ▼17.2% | ▼101.9% |

| 2018 | ▲1,931.2 | ▲41,328.4 | ▲1,421.6 | ▲30,423.2 | ▲2.3% | ▼1.7% | ▼15.3% | ▼100.5% |

| 2019 | ▲2,006.7 | ▲42,600.4 | ▲2.1% | ▼0.7% | ▼14.1% | ▼98.3% | ||

| 2020 | ▼-0.3% | ▲15.5% | ▲120.0% | |||||

| 2021 | ▲1,983.1 | ▲41,838.2 | ▲1,426.2 | ▲30,089.5 | ▲6.7% | ▲3.1% | ▼14.0% | ▼116.8% |

| 2022 | ▲2,269.7 | ▲47,669.6 | ▲6.2% | ▲8.8% | ▼13.0% | ▼111.6% | ||

| 2023 | ▲2,411.3 | ▲50,436.1 | ▲1,581.1 | ▲33,071.3 | ▲2.7% | ▼4.9% | ▼12.2% | ▼107.7% |

| 2024 | ▲2,516.3 | ▲52,012.4 | ▲1,647.1 | ▲34,045.1 | ▲2.9% | ▼3.5% | ▼11.3% | ▼105.6% |

| 2025 | ▲2,614.0 | ▲53,440.7 | ▲1,715.5 | ▲35,072.4 | ▲2.1% | ▼2.3% | ▼11.1% | ▼104.4% |

| 2026 | ▲2,711.8 | ▲54,864.9 | ▲1,772.0 | ▲35,852.4 | ▲1.8% | ▼1.9% | ▼11.2% | ▼104.3% |

| 2027 | ▲2,808.0 | ▲56,254.7 | ▲1,829.2 | ▲36,646.0 | ▲1.8% |

النقل

المواصلات بإسبانيا بشكل عام جيدة. شبكة السكك الحديدية الرئيسية تُدار من قبل شركة القطارات الحكومية (RENFE). المدن الإسبانية: مدريد، برشلونة، بلباو، فالنسيا، إشبيلية و بالما دي مايوركا تملك شبكة قطارات تحت أرضية (مترو)، كما أن حوالي أربعين مدينة تملك مطارها الخاص. أهم المطارات الدولية تتواجد في مدريد و برشلونة، اللذين يُعدا من ضمن أحد العشرة مطارات الأكثر ازدحاماً في أوروبا. شركة ايبيريا (Iberia) هي شركة الخطوط الجوية الوطنية.[104]

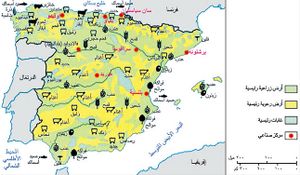

الموارد الطبيعية

أسبانيا فقيرة في الموارد الطبيعية. والبلاد بها قليل من الأرض الصالحة للزراعة، كما أنها تفتقر إلى الكثير من المواد الخام الصناعية المهمة.

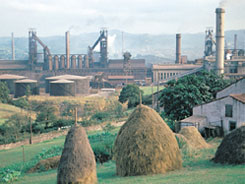

ومورد أسبانيا المعدني الرئيسي هو خام الحديد العالي الجودة الموجود في جبال كانتابريا. وتحتوي هذه الجبال على الفحم الحجري أيضًا. لكن المخزون منه في غالبه ذو نوعية سيئة. وتشمل المعادن الأخرى الموجودة في أسبانيا النحاس والرصاص والزئبق والبوتاس والبيرايت وملح الأرض والتيتانيوم واليورانيوم والزنك.

ومعظم أسبانيا ذات تربة فقيرة وكمية أمطار محدودة، مما يجعل زراعة المحاصيل أمرًا صعبًا. وكانت الغابات الكثيفة تغطي أجزاءً كبيرة من أسبانيا، لكن معظم الأشجار تم قطعها عبر الزمن. واليوم توجد مساحات قليلة بها غابات.

الصناعات الخدمية

هي تلك النشاطات الاقتصادية التي تنتج عنها خدمات، وليس منتجات. ويعمل حوالي نصف العمال في الصناعات الخدمية، وهذه الصناعات الخدمية مهمة على نحو خاص لاقتصاديات المدن الكبرى.

وتشكل خدمات المجتمع والحكومة والخدمات الشخصية أهم نوع من الصناعة الخدمية. وتشمل هذه الصناعة أنشطة اقتصادية مثل التعليم والعناية الصحية، والإدارة العامة، والجيش وتحليل المعلومات. كما أنها تشمل أيضًا خدمات صغيرة مثل الغسيل الجاف وإصلاح السيارات. ومدريد هي المركز الأهم للصناعة.

والبيع بالجملة وتجارة التجرئة هما ثاني أهم صناعة خدمية في أسبانيا. وبرشلونة هي المركز الرئيسي للتجارة. ويتم تصدير كميات كبيرة من النسيج والخمور والفواكه الحمضية من المدينة. كذلك فإن لإشبيليا تجارة كبيرة في الخمور والفواكه الحمضية. وبلباو هي منطقة التوزيع الرئيسية للحديد والفولاذ. سراقوسا مدينة رائدة في تجارة الآلات بالجملة، كما أن قرطاجنة هي مركز تجاري للمنتجات الزراعية. ومدريد هي المدينة الأهم لتجارة التجزئة بسبب عدد سكانها الكبير وعدد سياحها أيضًا.

وتشمل الصناعات الخدمية الأخرى الاتصالات، والتمويل والتأمين والعقار والفنادق والمطاعم والنقل والمرافق العامة. وسنتناول النقل والاتصال في هذا القسم فيما بعد.

الصناعة

تأتي أسبانيا ضمن منتجي السيارات الأوائل في العالم. والمنتجات المصنعة المهمة الأخرى تشمل: الإسمنت والمنتجات الكيميائية والأجهزة الكهربائية والحديد والفولاذ والآلات، والمنتجات البلاستيكية ومنتجات المطاط والسفن، والأحذية وملبوسات ومنسوجات أخرى. وبرشلونة وبلباو ومدريد مراكز الصناعة الرئيسية في البلاد. ومعظم مصانع الفولاذ وأحواض السفن الأسبانية موجودة في المناطق الشمالية. ويتم تصنيع القطن والأنسجة الصوفية والأحذية في منطقة برشلونة. وتختص مدريد بالإلكترونيات والصناعات الأخرى ذات التقنية العالية. وتقع مصانع السيارات الرئيسية في برشلونة ومدريد وبلنسية وسراقوسا.

تسيطر الحكومة على جزء كبير من إنتاج صناعة الفولاذ، والصناعات الرئيسية الأخرى. لكن معظم المصانع في أسبانيا يملكها ويقوم بتشغيلها القطاع الخاص. ويشارك في الاستثمار الشركات والأفراد من أقطار أخرى بدرجة كبيرة في الصناعات الأسبانية. وتجذبهم تكاليف العمالة المنخفضة، ونسب الضرائب المنخفضة وشروط مواتية للاستثمار في أسبانيا.

القوة الاقتصادية

Since the 1990s some Spanish companies have gained multinational status, often expanding their activities in culturally close Latin America, Eastern Europe and Asia. Spain is the second biggest foreign investor in Latin America, after the United States. Spanish companies have also expanded into Asia, especially China and India.[105] This early global expansion gave Spanish companies a competitive advantage over some of Spain's competitors and European neighbors. Another contribution to the success of Spanish firms may have to do with booming interest toward Spanish language and culture in Asia and Africa, but also a corporate culture that learned to take risks in unstable markets.

Spanish companies invested in fields like biotechnology and pharmaceuticals, or renewable energy (Iberdrola is the world's largest renewable energy operator[106]), technology companies like Telefónica, Abengoa, Mondragon Corporation, Movistar, Gamesa, Hisdesat, Indra, train manufacturers like CAF and Talgo, global corporations such as the textile company Inditex, petroleum companies like Repsol and infrastructure firms. Six of the ten biggest international construction firms specialising in transport are Spanish, lincluding Ferrovial, Acciona, ACS, OHL and FCC.[107]

Spain is equipped with a solid banking system as well, including two global systemically important banks, Banco Santander and BBVA.

البنية التحتية

In the 2012–13 edition of the Global Competitiveness Report Spain was listed 10th in the world in terms of first-class infrastructure. It is the 5th EU country with best infrastructure and ahead of countries like Japan or the United States.[108] In particular, the country is a leader in the field of high-speed rail, having developed the second longest network in the world (only behind China) and leading high-speed projects with Spanish technology around the world.[109][110]

The Spanish infrastructure concession companies, lead 262 transport infrastructure worldwide, representing 36% of the total, according to the latest rankings compiled by the publication Public Works Financing. The top three global occupy Spanish companies: ACS, Global Vía and Abertis, according to the ranking of companies by number of concessions for roads, railways, airports and ports in construction or operation in October 2012. Considering the investment, the first world infrastructure concessionaire is Ferrovial-Cintra, with 72,000 million euros, followed closely by ACS, with 70,200 million. Among the top ten in the world are also the Spanish Sacyr (21,500 million), FCC and Global Vía (with 19,400 million) and OHL (17,870 million).[111]

During 2013 Spanish civil engineering companies signed contracts around the world for a total of 40 billion euros, setting a new record for the national industry.[112]

The port of Valencia in Spain is the busiest seaport in the Mediterranean basin, 5th busiest in Europe and 30th busiest in the world.[113] There are four other Spanish ports in the ranking of the top 125 busiest world seaports (Algeciras, Barcelona, Las Palmas, and Bilbao); as a result, Spain is tied with Japan in the third position of countries leading this ranking.[113]

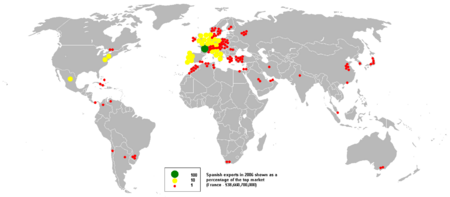

نمو الصادرات

During the boom years, Spain had built up a trade deficit eventually amounting a record equivalent to 10% of GDP (2007)[35] and the external debt ballooned to the equivalent of 170% of GDP, one of the highest among Western economies.[36] Then, during the economic downturn, Spain reduced significantly imports due to domestic consumption shrinking while – despite the global slowdown – it has been increasing exports and kept attracting growing numbers of tourists. Spanish exports grew by 4.2% in 2013, the highest rate in the European Union. As a result, after three decades of running a trade deficit Spain attained in 2013 a trade surplus.[35] Export growth was driven by capital goods and the automotive sector and the forecast was to reach a surplus equivalent to 2.5% of GDP in 2014.[114] Exports in 2014 were 34% of GDP, up from 24% in 2009.[115] The trade surplus attained in 2013 has been consolidated in 2014 and 2015.[36]

Despite slightly declining exports from fellow EU countries in the same period, Spanish exports continued to grow and in the first half of 2016 the country beat its own record to date exporting goods for 128,041 million euros; from the total, almost 67% were exported to other EU countries.[116] During this same period, from the 70 members of the World Trade Organization (whose combined economies amount to 90% of global GDP), Spain was the country whose exports had grown the most.[117]

In 2016, exports of goods hit historical highs despite a global slowdown in trade, making up for 33% of the total GDP (by comparison, exports represent 12% of GDP in the United States, 18% in Japan, 22% in China or 45% in Germany).[99]

In all, by 2017 foreign sales have been rising every year since 2010, with a degree of unplanned import substitution -a rather unusual feat for Spain when in an expansive phase- which points to structural competitive gains.[118] According to the most recent 2017 data, about 65% of the country's exports go to other EU members.[119]

القطاعات

The Spanish benchmark stock market index is the IBEX 35, which as of 2016 is led by banking (including Banco Santander and BBVA), clothing (Inditex), telecommunications (Telefónica) and energy (Iberdrola).

In 2022, the sector with the highest number of companies registered in Spain is Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate with 2,656,178 companies followed by Services and Retail Trade with 2,090,320 and 549,395 companies respectively.[120]

التجارة الخارجية

Traditionally until 2008, most exports and imports from Spain were held with the countries of the European Union: France, Germany, Italy, UK and Portugal.

In recent years foreign trade has taken refuge outside the European Union. Spain's main customers are Latin America, Asia (Japan, China, India), Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Egypt) and the United States. Principal trading partners in Asia are Japan, China, South Korea, Taiwan. In Africa, countries producing oil (Nigeria, Algeria, Libya) are important partners, as well as Morocco. Latin American countries are very important trading partners, like Argentina, Mexico, Cuba (tourism), Colombia, Brazil, Chile (food products) and Mexico, Venezuela and Argentina (petroleum). [2] Archived 17 نوفمبر 2018 at the Wayback Machine

After the crisis that began in 2008 and the fall of the domestic market, Spain (since 2010) has turned outwards widely increasing the export supply and export amounts.[121] It has diversified its traditional destinations and has grown significantly in product sales of medium and high technology, including highly competitive markets like the US and Asia. [3] Archived 17 نوفمبر 2018 at the Wayback Machine

| أكبر الشركاء التجاريين لإسبانيا في 2015[122] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

السياحة

During the last four decades Spain's foreign tourist industry has grown into the second-biggest in the world. A 2015 survey by the World Economic Forum proclaimed the country's tourism industry as the world's most competitive.[123] The 2017 survey repeated this finding.[124]

By 2018 the country was the second most visited country in the world, overtaking the US and not far behind France.[125] With 83.7 million visitors, the country broke in 2019 its own tourism record for the tenth year in a row.[126]

The size of the business has gone from approximately €40 billion in 2006[13] to about €77 billion in 2016.[127] In 2015 the total value of foreign and domestic tourism came to nearly 5% of the country's GDP and provided employment for about 2 million people.[128]

The headquarters of the World Tourism Organization are located in Madrid.[129]

صناعة السيارات

The automotive industry is one of the largest employers in the country. In 2015 Spain was the 8th largest automobile producer country in the world and the 2nd largest car manufacturer in Europe after Germany.[130]

By 2016, the automotive industry was generating 8.7 percent of Spain's gross domestic product, employing about nine percent of the manufacturing industry.[130] By 2008 the automobile industry was the 2nd most exported industry[131] while in 2015 about 80% of the total production was for export.[130]

German companies poured €4.8 billion into Spain in 2015, making the country the second-largest destination for German foreign direct investment behind only the U.S. The lion's share of that investment —€4 billion— went to the country's auto industry.[130]

الطاقة

Spanish electricity usage in 2010 constituted 88% of the EU15 average (EU15: 7,409 kWh/person), and 73% of the OECD average (8,991 kWh/person).[132]

In 2023, Spain consumed 244,686 gigawatt hours (GWh) of electricity, a 2.3% decline from 2022.[133]

Spain is one of the world leaders in renewable energies, both as a producer of renewable energy itself and as an exporter of such technology. In 2013 it became the first country ever in the world to have wind power as its main source of energy.[134]

الاقتصاد الزراعي

Agribusiness has been another segment growing aggressively over the last few years. At slightly over 40 billion euros, in 2015 agribusiness exports accounted for 3% of GDP and over 15% of the total Spanish exports.[135]

The boom was shaped during the 2004-2014 period, when Spain's agribusiness exports grew by 95% led by pork, wine and olive oil.[136] By 2012 Spain was by far the biggest producer of olive oil in the world, accounting for 50% of the total production worldwide.[137] By 2013 the country became the world's leading producer of wine;[138] in 2014[139] and 2015[140] Spain was the world's biggest wine exporter. However, poor marketing and low margins remain an issue, as shown by the fact that the main importers of Spanish olive oil and wine (Italy[115] and France,[140] respectively) buy bulk Spanish produce which is then bottled and sold under Italian or French labels, often for a significant markup.[115][139]

Spain is the largest producer and exporter in the EU of citrus fruit (oranges, lemons and small citrus fruits), peaches and apricots.[141] It is also the largest producer and exporter of strawberries in the EU.[142]

السلع الغذائية بالقطاعي

In 2020, the food distribution sector was dominated by Mercadona (24.5% market share), followed by Carrefour (8.4%), Lidl (6.1%), DIA (5.8), Eroski (4.8), Auchan (3.4%), regional distributors (14.3%) and other (32.7%).[143]

التعدين

In 2019, the country was the 7th largest producer of gypsum[144] and the 10th world's largest producer of potash,[145] in addition to being the 15th largest world producer of salt.[146]

Copper (of which the country is the second producer in Europe) is primarily extracted in the Iberian Pyrite Belt.[147]

The province of Granada features two mines of Celestine, making the country a major producer of strontium concentrates.[148]

الاندماج والاستحواذ

Between 1985 and 2018 around 23,201 deals have been announced where Spanish companies participated either as the acquirer or the target. These deals cumulate to an overall value of 1,935 bil. USD (1,571.8 bil. EUR). Here is a list of the top 10 deals with Spanish participation:

| تاريخ الإعلان | اسم المستحوذ | Acquiror mid-industry | Acquiror nation | Target name | Target mid-industry | Target nation | Value of transaction ($mil) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10/31/2005 | Telefónica SA | Telecommunications Services | Spain | O2 PLC | Wireless | United Kingdom | 31,659.40 |

| 04/02/2007 | Investor Group | Other Financials | Italy | Endesa SA | Power | Spain | 26,437.77 |

| 05/09/2012 | FROB | Other Financials | Spain | Banco Financiero y de Ahorros | Banks | Spain | 23,785.68 |

| 11/28/2006 | Iberdrola SA | Power | Spain | Scottish Power PLC | Power | United Kingdom | 22,210.00 |

| 02/08/2006 | Airport Dvlp & Invest Ltd | Other Financials | Spain | BAA PLC | Transportation & Infrastructure | United Kingdom | 21,810.57 |

| 03/14/2007 | Imperial Tobacco Overseas Hldg | Other Financials | United Kingdom | Altadis SA | Tobacco | Spain | 17,872.72 |

| 07/23/2004 | Santander Central Hispano SA | Banks | Spain | Abbey National PLC | Banks | United Kingdom | 15,787.49 |

| 07/17/2000 | Vodafone AirTouch PLC | Wireless | United Kingdom | Airtel SA | Other Telecom | Spain | 14,364.85 |

| 12/26/2012 | Banco Financiero y de Ahorros | Banks | Spain | Bankia SA | Banks | Spain | 14,155.31 |

| 04/02/2007 | Enel SpA | Power | Italy | Endesa SA | Power | Spain | 13,469.98 |

انظر أيضا

- List of largest Spanish companies

- Automotive industry in Spain

- Tourism in Spain

- Agriculture in Spain

- Spanish Miracle

- Economic history of Spain

- Asian immigrants and the economy of Spain

المصادر

- ^ "INEbase / Continuous Population Statistics (CPS). 1 January 2025. Provisional data". ine.es. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "World Economic Outlook database: October 2024". imf.org. International Monetary Fund.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Global Growth: Divergent and Uncertain". International Monetary Fund. 17 January 2025.

- ^ "INE". Retrieved 9 February 2025.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةINE-inflation - ^ "People at risk of poverty or social exclusion". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat.

- ^ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat.

- ^ "Labor force, total - Spain". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ "Tasa de empleo". www.ine.es. INE. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ "Percentage distribution of employed persons by economic sector and province". INE Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Retrieved 9 February 2025.

- ^ "Unemployment in the EU in January 2025". Eurostat. Retrieved 12 March 2025.

- ^ أ ب "Economically Active Population Survey. Fourth Quarter 2024". INE Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ أ ب "Home". The Global Guru. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Economic report" (PDF). Bank of Spain. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ "Ease of Doing Business in Spain". Doingbusiness.org. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "CIA World Factbook". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ أ ب "Foreign direct investment (FDI) flows is the value of cross-border transactions related to direct investment over time". OECD. Retrieved 9 February 2025.

- ^ أ ب "World Economic Outlook Database. October 2024". IMF. Retrieved 9 February 2025.

- ^ "Spain public debt" (in الإسبانية). elpaís.es. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ "Spain public debt" (in الإسبانية). bde.es. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ أ ب "Euro area government deficit at 3.6% and EU at 3.5% of GDP". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Sovereigns rating list". Standard & Poor's. Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ "Moody's changes outlook on Spain to positive". Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ "Fitch Revises Spain's Outlook to Positive; Affirms IDR at 'A-'". Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ "Scope upgrades Spain's long-term credit ratings to A and changes the Outlook to Stable". Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ Official report on Spanish recent Macroeconomics, including tables and graphics, La Moncloa, http://www.la-moncloa.es/NR/rdonlyres/2E85E75E-E2D9-4148-B1DF-950B06696A6C/74823/Chapter_2.PDF, retrieved on 13 August 2008

- ^ Kenworthy, Lane (1999). "Do Social-Welfare Policies Reduce Poverty? A Cross-National Assessment" (PDF). Social Forces. 77 (3): 1119–1139. doi:10.2307/3005973. JSTOR 3005973. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2013.

- ^ Moller, Stephanie; Huber, Evelyne; Stephens, John D.; Bradley, David; Nielsen, François (2003). "Determinants of Relative Poverty in Advanced Capitalist Democracies". American Sociological Review. 68 (1): 22–51. doi:10.2307/3088901. JSTOR 3088901.

- ^ "Social Expenditure – Aggregated data". OECD.

- ^ "El PIB español sigue sin recuperar el volumen previo a la crisis" (in الإسبانية). Expansión. 6 February 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ "Spain". 23 April 2016.

- ^ "Spain | European Stability Mechanism". esm.europa.eu. 23 April 2016. Retrieved 2019-09-29.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Bolaños, Alejandro (28 February 2014). "España logra en el año 2013 el primer superávit exterior en tres décadas". El País.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Bolaños, Alejandro (2016-02-29). "El superávit exterior de la economía española supera el 1,5% del PIB en 2015". El País (in الإسبانية). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Spanish economy: Spanish economy grew 3.2% in 2015 | Economy and Business | EL PAÍS English Edition". 29 January 2016.

- ^ أ ب "Fitch Affirms Spain at 'BBB+'; Outlook Stable". Reuters. 29 January 2016.

- ^ أ ب "España recupera en sólo 2 años el 85% del PIB perdido durante la crisis" (in الإسبانية). La Razón. 17 October 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ أ ب "How Spain became the West's superstar economy". 30 April 2015. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "La economía sumergida mueve más de cuatro millones de empleos". 25 January 2016.

- ^ "La economía sumergida en España, cerca del 20% del PIB". Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ "España sigue entre los países con más economía sumergida". Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ "UPDATE 2-Spain's economy returns to pre-pandemic levels in first quarter". Reuters (in الإنجليزية). 2023-06-23. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "Economic forecast for Spain". economy-finance.ec.europa.eu (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- ^ "Macroeconomic projections and quarterly report on the Spanish economy. December 2024". bde.es. 17 December 2024. Retrieved 2024-12-17.

- ^ Payne, Stanley G. (2006). The Collapse of the Spanish Republic 1933-1936. United States: Yale University Press.

- ^ أ ب ت Pérez, Claudi (18 June 2014). "La renta por habitante española retrocede 16 años en comparación con la UE". El País.

- ^ Login required – Eurostat 2004 GDP figures Archived 26 مارس 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ No camp grows on both Right and Left, European Foundation Intelligence Digest, http://www.europeanfoundation.org/docs/id210.pdf, retrieved on 9 August 2008

- ^ "Spain's Economy: Closing the Gap". OECD Observer. May 2005. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ^ OECD report for 2006, OECD, http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/51/21/37392840.pdf, retrieved on 9 August 2008

- ^ (PDFaugest 588)Bank of Spain Economic Bulletin 07/2005, Bank of Spain, http://www.bde.es/informes/be/boleco/2005/be0507e.pdf

- ^ Spain (Economy section), CIA, 23 April 2009, https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/spain/, retrieved on 1 May 2009, "GDP growth in 2008 was 1.3%, well below the 3% or higher growth the country enjoyed from 1997 through 2007."

- ^ Recession to hit Germany, UK and Spain, 10 September 2008, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/cf5d0f08-7f49-11dd-a3da-000077b07658.html?nclick_check=1, retrieved on 11 September 2008

- ^ "Hashtag Spain". Hashtag Spain (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "And worse to come". The Economist. 2009-01-22. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ Abellán, L. (30 August 2008), "El tirón de las importaciones eleva el déficit exterior a más del 10% del PIB" (in es), El País, Economía (Madrid), http://www.elpais.com/articulo/economia/tiron/importaciones/eleva/deficit/exterior/PIB/elpepueco/20080830elpepieco_3/Tes, retrieved on 2 May 2009

- ^ Crawford, Leslie (8 June 2006), "Boomtime Spain waits for the bubble to burst", Financial Times, Europe (Madrid), ISSN 0307-1766, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/32cd35d0-f68b-11da-b09f-0000779e2340.html?nclick_check=1

- ^ Europa Press (2008), "La economía española retrocede un 0.2% por primera vez en 15 años" (in es), El País (Madrid), 31 October 2008, http://www.elpais.com/articulo/economia/economia/espanola/retrocede/primera/vez/anos/elpepueco/20081031elpepueco_8/Tes

- ^ Economist Intelligence Unit (28 April 2009), Spain Economic Data, The Economist, https://www.economist.com/countries/Spain/profile.cfm?folder=Profile-Economic%20Data, retrieved on 2 May 2009

- ^ Day, Paul; Reuters (18 February 2009), "UPDATE 1 – Spain facing long haul as recession confirmed", Forbes (Madrid), https://www.forbes.com/feeds/afx/2009/02/18/afx6064245.html, retrieved on 2 May 2009

- ^ "FMI empeora sus pronósticos de la economía española". Finanzas.com. 8 July 2009. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ Casqueiro, Javier (19 July 2016). "Spain's deficit: Spain rejects EU deficit reprisals, insisting economy will grow above 3% this year". El País. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Tadeo, María; Smyth, Sharon R. (29 November 2016). "Housing Crash Turns Spain's Young into Generation Rent". Bloomberg. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ "OECD figures". OECD. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ Tremlett, Giles (26 July 2006). "Economic statistics". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ "Official report on Spanish recent Macroeconomics, including tables and graphics" (PDF). La Moncloa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ Minder, Raphael; Kanter, James (2012-11-28). "Spanish Banks Agree to Layoffs and Other Cuts to Receive Rescue Funds in Return". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ Giles Tremlett in Madrid (8 June 2012). "The Guardian, Spain's savings banks' 8 June 2012". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Mallet, Victor (21 June 2012). "The bank that broke Spain Financial Times". Financial Times. Ft.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ (in إنگليزية) Merkel Economy Adviser Says Greece Bailout Should Bring Penalty, http://www.businessweek.com/news/2010-02-15/merkel-economy-adviser-says-greece-bailout-should-bring-penalty.html, retrieved on 15 February 2010

- ^ Ross, Emma (18 March 2010). "Zapatero's Bid to Avoid Greek Fate Hobbled by Regions". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ أ ب "Spain's jobless rate soars to 17%", BBC America, Business (BBC News), 24 April 2009, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/8016364.stm, retrieved on 2 May 2009

- ^ أ ب "EPA: Evolución del mercado laboral en España". El País. 28 January 2016.

- ^ Agencias (4 November 2008), "La recesión económica provoca en octubre la mayor subida del paro de la historia" (in es), El País, Internacional (Madrid), http://www.elpais.com/articulo/internacional/recesion/economica/provoca/octubre/mayor/subida/paro/historia/elpepuint/20081104elpepuint_8/Tes, retrieved on 2 May 2009

- ^ "Builders' nightmare", The Economist, Europe (Madrid), 4 December 2008, https://www.economist.com/world/europe/displaystory.cfm?story_id=12725415, retrieved on 2 May 2009

- ^ أ ب "Iberian_Dawn". The Economist. 2 August 2014.

- ^ "Two-tier flexibility". The Economist. 9 July 2009.

- ^ González, Sara (1 May 2009), "300.000 inmigrantes han vuelto a su país por culpa del paro" (in es), El Periódico de Catalunya, Sociedad (Barcelona: Grupo Zeta), http://www.elperiodico.com/default.asp?idpublicacio_PK=46&idioma=CAS&idnoticia_PK=608508&idseccio_PK=1021, retrieved on 14 May 2009

- ^ أ ب "EPA: El paro cae al 24,47% con el primer aumento anual de ocupación desde 2008". 24 July 2014.

- ^ García-Pérez, J. Ignacio; Muñoz-Bullón, Fernando (2011-03-01). "Transitions into Permanent Employment in Spain: An Empirical Analysis for Young Workers". British Journal of Industrial Relations (in الإنجليزية). 49 (1): 103–143. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.597.6996. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8543.2009.00750.x. ISSN 1467-8543. S2CID 154392095.

- ^ Domínguez-Mujica, Josefina; Guerra-Talavera, Raquel; Parreño-Castellano, Juan Manuel (2014-12-01). "Migration at a Time of Global Economic Crisis: The Situation in Spain". International Migration (in الإنجليزية). 52 (6): 113–127. doi:10.1111/imig.12023. ISSN 1468-2435.

- ^ Ayllón, Sara (2015-12-01). "Youth Poverty, Employment, and Leaving the Parental Home in Europe". Review of Income and Wealth (in الإنجليزية). 61 (4): 651–676. doi:10.1111/roiw.12122. ISSN 1475-4991. S2CID 153673821.

- ^ Ahn, Namkee; De La Rica, Sara; Ugidos, Arantza (1999-08-01). "Willingness to Move for Work and Unemployment Duration in Spain" (PDF). Economica (in الإنجليزية). 66 (263): 335–357. doi:10.1111/1468-0335.00174. ISSN 1468-0335.

- ^ Wölfl, Anita (2013). "Improving Employment Prospects for Young Workers in Spain". OECD Economics Department Working Papers. doi:10.1787/5k487n7hg08s-en.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "El paro registra una caída récord de 310.400 personas y se crean 402.400 empleos, la mayor cifra en 9 años". 24 July 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Tobias Buck (4 January 2017). "Drop in Spanish jobless total is biggest on record". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022.

- ^ Maria Tadeo (26 January 2017). "Spain Unemployment Falls to Seven-Year Low Amid Budget Talks". Bloomberg.

- ^ "Jobs in Spain: Easter hirings bring record monthly drop in unemployment to Spain". El País. 4 May 2017.

- ^ أ ب "Working in Spain: Unemployment: Social Security affiliations have best May since 2001". El País. 2 June 2017.

- ^ María Tadeo (27 July 2017). "Spanish Unemployment Falls to Lowest Since Start of 2009". Bloomberg.

- ^ Antonio Maqueda (27 July 2017). "EPA: El paro baja de los cuatro millones por primera vez desde comienzos de 2009". El País (in الإسبانية).

- ^ Manuel V. Gómez (25 October 2018). "EPA: La tasa de paro baja del 15% por primera vez desde 2008". El País (in الإسبانية).

- ^ "Spain Takes an Economic Gamble on an Unprecedented Wage Hike". Bloomberg. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "Spain: Keeping good momentum". Corporate (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2024-08-09.

- ^ "España elige el peor momento para ingresar en el club de los países ricos". Publico.es. 24 November 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ أ ب ت Antonio Maqueda (30 January 2017). "GDP growth: Spanish economy outperforms expectations to grow 3.2% in 2016". El País.

- ^ أ ب Antonio Maqueda (28 July 2017). "EPA: El PIB crece un 0,9% y recupera lo perdido con la crisis". El País (in الإسبانية). Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Lluís Pellicer; Cristina Delgado (3 July 2017). "Property in Spain: Spain's new real estate boom: the rental market". El País. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Maria Tadeo; Sharon R. Smyth (21 July 2017). "The Spanish Housing Market Is Finally Recovering". Bloomberg.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects".

- ^ إسبانيا، الموسوعة المعرفية الشاملة

- ^ "A good bet?", The Economist, Business (Madrid), 30 April 2009, https://www.economist.com/business/displaystory.cfm?story_id=13579705, retrieved on 14 May 2009

- ^ "Spain's Iberdrola signs investment accord with Gulf group Taqa". Forbes. 25 May 2008. Archived from the original on 7 June 2010.

- ^ "Big in America?", The Economist, Business (Madrid), 8 April 2009, https://www.economist.com/business/displaystory.cfm?story_id=13447445, retrieved on 14 May 2009

- ^ "Fomento ultima un drástico ajuste de la inversión del 17% en 2013". Cincodias.com. 19 September 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ "España, technology for life". Spaintechnology.com. 9 August 2012. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ "Saudi railway to be built by Spanish-led consortium". Bbc.co.uk. 26 October 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ "Concesionarias españolas operan el 36% de las infraestructuras mundiales | Mis Finanzas en Línea". Misfinanzasenlinea.com. 11 November 2012. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ Jiménez, Miguel (15 February 2014). "Pastor prevé que el AVE del desierto abra la puerta a más obras en Arabia Saudí". El País.

- ^ أ ب "El puerto de Valencia es el primero de España y el trigésimo del mundo". El País. 23 August 2013.

- ^ "La CE prevé que España tendrá superávit comercial en 2014". Comfia.info. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ أ ب ت "A pressing issue". The Economist. 2014-04-19. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "El récord de exportaciones españolas reduce un 31,4% el déficit comercial". El País (in الإسبانية). 2016-08-19. ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ Molina, Carlos (19 September 2016). "España, el país del mundo en el que más suben las exportaciones". Cinco Días (in الإسبانية). Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةExportsTiger - ^ Ministerio de Economía Industria y Competitividad (22 August 2017). "Las exportaciones crecen un 10% hasta junio y siguen marcando máximos históricos" (in الإسبانية). Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Industry Breakdown of Companies in Spain". HitHorizons.

- ^ "Spain Business Directory | List of Companies". bizpages.org.

- ^ "Spain trade balance, exports, imports by country 2015 | WITS Data".

- ^ "Spain has the world's most competitive tourism industry". El País. 7 May 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ "Country profiles". Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2017 (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- ^ "List of countries with the highest international tourist numbers". World Economic Forum (in الإنجليزية). 8 June 2020. Retrieved 2020-07-14.

- ^ "Spain's 2019 tourist arrivals hit new record high, minister upbeat on trend". Reuters (in الإنجليزية). 2020-01-20. Retrieved 2020-07-14.

- ^ "75 million and counting: Spain shattered its own tourism record in 2016". El País. 13 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ ">> Exceptional lifestyle". Invest in Spain. Archived from the original on 18 November 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ "Where we are | World Tourism Organization UNWTO". Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Méndez-Barreira, Victor (2016-08-07). "Car Makers Pour Money Into Spain". Wall Street Journal (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ ">> Spain in numbers". Invest in Spain. Archived from the original on 26 March 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ Energy in Sweden, Facts and figures, The Swedish Energy Agency, (in Swedish: Energiläget i siffror), Table: Specific electricity production per inhabitant with breakdown by power source (kWh/person), Source: IEA/OECD 2006 T23 Archived 4 يوليو 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 2007 T25 Archived 4 يوليو 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 2008 T26 Archived 4 يوليو 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 2009 T25 Archived 20 يناير 2011 at the Wayback Machine and 2010 T49 Archived 16 أكتوبر 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Lombardi, Pietro (2024-01-04). "Spain's electricity demand drops for second year in a row".

- ^ "Spain breezes into record books as wind power becomes main source of energy | Spain | EL PAÍS English Edition". 15 January 2014.

- ^ "La facturación de las exportaciones agroalimentarias españolas creció un 8,36% el año pasado". abc (in الإسبانية). 2016-04-25. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "La exportación de la industria alimentaria creció el 5,5% en 2014". El País. 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Spain's bumper olive years come to bitter end". BBC News. 29 January 2013.

- ^ "Spain's wine surplus overflows across globe following year of unusual weather". TheGuardian.com. 19 March 2014.

- ^ أ ب "Spain becomes world's biggest wine exporter in 2014". the Guardian (in الإنجليزية). 2015-03-06. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ أ ب Maté, Vidal (2016-02-29). "Spain tops global wine export table, but is selling product cheap". EL PAÍS English Edition (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Agricultural production - orchards". ec.europa.eu (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ "La vida efímera de la fresa". ELMUNDO (in الإسبانية). 2016-03-09. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- ^ Romera, Javier (23 February 2021). "Mercadona baja precios, pero descarta entrar en una guerra con Lidl y Aldi". El Economista.

- ^ "USGS Gypsum Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "USGS Potash Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "USGS Salt Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "La fiebre de la minería en España: el auge de los nuevos metales". rtve.es. 15 March 2021.

- ^ "Estroncio 2011" (PDF). IGME. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

وصلات خارجية

مصادر إحصائية

- Banco de España (Spanish Central Bank); features the latest and in depth statistics

- Statistical Institute of Andalusia

- National Institute of Statistics

- Statistical Institute of Catalonia

- Statistical Institute of Galicia

- OECD's Spain country Web site and OECD Economic Survey of Spain

قراءات إضافية

- Article: Investing in Spain by Nicholas Vardy - September, 2006. A global investor's discussion of Spain's economic boom.

- The Pain in Spain: On May Day, Nearly 1 in 5 are Jobless by Andrés Cala, The Christian Science Monitor, May 1, 2009

- Alternatives to Fiscal Austerity in Spain from the Center for Economic and Policy Research, July 2010

- O'Neill, Michael F.; McGettigan, Gerard (2005), "Spanish biotechnology: anyone for PYMEs?", Drug Discovery Today, News and Comment (London: Elsevier) 10 (16): 1078-1081, 15 August 2005, doi:, ISSN 1359-6446

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Articles with إنگليزية-language sources (en)

- Articles with dead external links from June 2016

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2022

- اقتصاد إسپانيا

- اقتصاد عضو الاتحاد الاوروبي

- اقتصادات أعضاء منظمة التجارة العالمية

- اقتصادات أعضاء منظمة التعاون والتنمية الاقتصادية