حرب خاطفة

الحرب الخاطفة Blitzkrieg هي نوع من الحرب سريعة الحركة، طورها الألمان أثناء الحرب العالمية الثانية (1939- 1945م). في الحرب الخاطفة حيث تقوم دبابات البانزر السريعة، أو القوات المختلفة، بهجوم ساحق على خطوط العدو ثم تكتسح إلى الداخل، تدعمها قاذفات الانقضاض. وطور الروس خطة الدفاع في العمق ليقابلوا بها الحرب الخاطفة. وكانوا يتركون الألمان يكتسحون للداخل، ثم يفرون من شراكهم أو يحيطون بالألمان المتقدمين ويدمرونهم. وقد سُميِّت غارات الألمان على لندن والمدن البريطانية الأخرى أثناء عامي 1940م، 1941م، بالغارات الجوية الخاطفة.

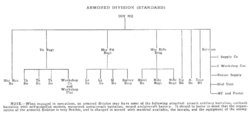

طورت عدة دول المبادئ التي قام عليها مفهوم الحرب الخاطفة خلال العشرينيات والثلاثينيات من القرن الماضي، لكن الجيش الألماني (الفيرماخت) كان من طبق هذا المفهوم واستخدمه على نطاق واسع خلال الحرب العالمية الثانية. تتضمن الحرب الخاطفة شن قذف مدفعي مكثف يهدف إلى إلحاق أكبر قدر من الخسائر بقوات العدو، بالإضافة إلى التأثير على معنويات الجنود المدافعين. ثم يعقب ذلك هجوماً بالوحدات الجوية من قاذفات ومقاتلات لتدمير النقاط الدفاعية للعدو، بعد ذلك يأتي دور وحدات المدرعات التي تتبعها وحدات مشاة ميكانيكية مجهزة بآليات مدرعة ومدفعية مضادة للطائرات.

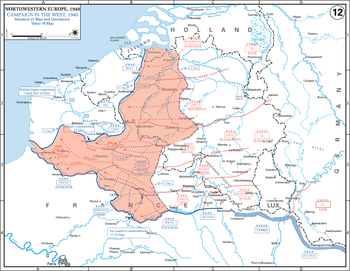

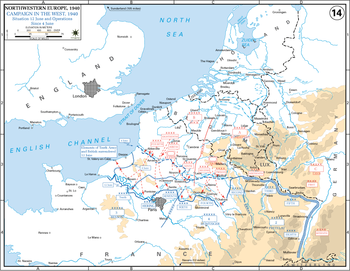

German maneuver operations were successful during the campaigns of 1939–1941, involving the invasions of Belgium, the Netherlands, and France and, by 1940, the term blitzkrieg was being extensively used in Western media.[1][2] Blitzkrieg operations capitalised on surprise penetrations, such as that in the Ardennes forest, the Allies' general lack of preparedness, and their inability to match the pace of the German attack. During the Battle of France, the French made attempts to reform defensive lines along rivers but were frustrated when German forces arrived first and pressed on.[2]

Despite being common in German and English-language journalism during World War II, the word Blitzkrieg was never used as an official military term by the Wehrmacht, except for propaganda, and it was never officially adopted as a concept or doctrine.[1][أ] According to David Reynolds, "Hitler himself called the term Blitzkrieg 'a completely idiotic word' (ein ganz blödsinniges Wort)".[3] Some senior German officers, including Kurt Student, Franz Halder, and Johann Adolf von Kielmansegg, even disputed the idea that it was a military concept. Kielmansegg asserted that what many regarded as blitzkrieg was nothing more than "ad hoc solutions that simply popped out of the prevailing situation". Kurt Student described it as ideas that "naturally emerged from the existing circumstances" as a response to operational challenges.[4]

In 2005, the historian Karl-Heinz Frieser summarized blitzkrieg as the result of German commanders using the latest technology in the most advantageous way, according to traditional military principles, and employing "the right units in the right place at the right time".[5] Modern historians now understand blitzkrieg as the combination of traditional German military principles, methods and doctrines of the 19th century with the military technology of the interwar period.[6] Modern historians use the term casually as a generic description for the style of maneuver warfare practised by Germany during the early part of World War II, rather than as an explanation.[ب] According to Frieser, in the context of the thinking of Heinz Guderian on mobile combined arms formations, blitzkrieg can be used as a synonym for modern maneuver warfare on the operational level.[7]

Definition

Common interpretation

The traditional meaning of "blitzkrieg" is that of German tactical and operational methodology during the first half of the Second World War that is often hailed as a new method of warfare. The word, meaning "lightning war" or "lightning attack" in its strategic sense describes a series of quick and decisive short battles to deliver a knockout blow to an enemy state before it can fully mobilize. Tactically, blitzkrieg is a coordinated military effort by tanks, motorized infantry, artillery and aircraft, to create an overwhelming local superiority in combat power, to defeat the opponent and break through its defences.[8][9] Blitzkrieg as used by Germany had considerable psychological or "terror" elements,[ت] such as the Jericho Trompete, a noise-making siren on the Junkers Ju 87 dive bomber, to affect the morale of enemy forces.[ث] The devices were largely removed when the enemy became used to the noise after the Battle of France in 1940, and instead, bombs sometimes had whistles attached.[10][11] It is also common for historians and writers to include psychological warfare by using fifth columnists to spread rumours and lies among the civilian population in the theatre of operations.[8]

Origin of term

The origin of the term blitzkrieg is obscure. It was never used in the title of a military doctrine or handbook of the German Army or Air Force,[1] and no "coherent doctrine" or "unifying concept of blitzkrieg" existed; German High Command mostly referred to the group of tactics as "Bewegungskrieg" (Maneuver Warfare).[12] The term seems to have been rarely used in the German military press before 1939, and recent research at the German Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt, at Potsdam, found it in only two military articles from the 1930s.[ج] Both used the term to mean a swift strategic knockout, rather than a radically new military doctrine or approach to war.

The first article (1935) dealt primarily with supplies of food and materiel in wartime. The term blitzkrieg was used in reference to German efforts to win a quick victory in the First World War but was not associated with the use of armored, mechanized or air forces. It argued that Germany must develop self-sufficiency in food because it might again prove impossible to deal a swift knockout to its enemies, which would lead to a long war.[13]

In the second article (1938), launching a swift strategic knockout was described as an attractive idea for Germany but difficult to achieve on land under modern conditions (especially against systems of fortification like the Maginot Line) unless an exceptionally high degree of surprise could be achieved. The author vaguely suggested that a massive strategic air attack might hold out better prospects, but the topic was not explored in detail.[13]

A third relatively early use of the term in German occurred in Die Deutsche Kriegsstärke (German War Strength) by Fritz Sternberg, a Jewish Marxist political economist and refugee from Nazi Germany, published in 1938 in Paris and in London as Germany and a Lightning War. Sternberg wrote that Germany was not prepared economically for a long war but might win a quick war ("Blitzkrieg"). He did not go into detail about tactics or suggest that the German armed forces had evolved a radically new operational method. His book offered scant clues as to how German lightning victories might be won.[13]

In English and other languages, the term had been used since the 1920s.[14] The term was first used in the publications of Ferdinand Otto Miksche, first in the magazine "Army Quarterly",[ح] and in his 1941 book Blitzkrieg, in which he defined the concept.[15] In September 1939, Time magazine termed the German military action as a "war of quick penetration and obliteration – Blitzkrieg, lightning war".[16] After the invasion of Poland, the British press commonly used the term to describe German successes in that campaign. J. P. Harris called the term "a piece of journalistic sensationalism – a buzz-word with which to label the spectacular early successes of the Germans in the Second World War". The word was later applied to the bombing of Britain, particularly London, hence "The Blitz".[17]

The German popular press followed suit nine months later, after the Fall of France in 1940; thus, although the word had first been used in Germany, it was popularized by British journalism.[18][19] Heinz Guderian referred to it as a word coined by the Allies: "as a result of the successes of our rapid campaigns our enemies ... coined the word Blitzkrieg".[20] After the German failure in the Soviet Union in 1941, the use of the term began to be frowned upon in Nazi Germany, and Hitler then denied ever using the term and said in a speech in November 1941, "I have never used the word Blitzkrieg, because it is a very silly word".[21] In early January 1942, Hitler dismissed it as "Italian phraseology".[22][23]

Military evolution, 1919–1939

Germany

In 1914, German strategic thinking derived from the writings of Carl von Clausewitz (1 June 1780 – 16 November 1831), Helmuth von Moltke the Elder (26 October 1800 – 24 April 1891) and Alfred von Schlieffen (28 February 1833 – 4 January 1913), who advocated maneuver, mass and envelopment to create the conditions for a decisive battle (Vernichtungsschlacht). During the war, officers such as Willy Rohr developed tactics to restore maneuver on the battlefield. Specialist light infantry (Stosstruppen, "storm troops") were to exploit weak spots to make gaps for larger infantry units to advance with heavier weapons, exploit the success and leave isolated strong points to the troops that were following up. Infiltration tactics were combined with short hurricane artillery bombardments, which used massed artillery. Devised by Colonel Georg Bruchmüller, the attacks relied on speed and surprise, rather than on weight of numbers. The tactics met with great success in Operation Michael, the German spring offensive of 1918 and restored temporarily the war of movement once the Allied trench system had been overrun. The German armies pushed on towards Amiens and then Paris and came within 120 كيلومتر (75 mi) before supply deficiencies and Allied reinforcements halted the advance.[24]

The historian James Corum criticised the German leadership for failing to understand the technical advances of the First World War, conducting no studies of the machine gun prior to the war and giving tank production the lowest priority during the war.[25] After Germany's defeat, the Treaty of Versailles limited the Reichswehr to a maximum of 100,000 men, which prevented the deployment of mass armies. The German General Staff was abolished by the treaty but continued covertly as the Truppenamt (Troop Office) and was disguised as an administrative body. Committees of veteran staff officers were formed within the Truppenamt to evaluate 57 issues of the war to revise German operational theories.[26] By the time of the Second World War, their reports had led to doctrinal and training publications, including H. Dv. 487, Führung und Gefecht der verbundenen Waffen ("Command and Battle of the Combined Arms)", known as Das Fug (1921–1923) and Truppenführung (1933–1934), containing standard procedures for combined-arms warfare. The Reichswehr was influenced by its analysis of pre-war German military thought, particularly infiltration tactics since at the end of the war, they had seen some breakthroughs on the Western Front and the maneuver warfare which dominated the Eastern Front.

On the Eastern Front, the war did not bog down into trench warfare since the German and the Russian Armies fought a war of maneuver over thousands of miles, which gave the German leadership unique experience that was unavailable to the trench-bound Western Allies.[27] Studies of operations in the East led to the conclusion that small and coordinated forces possessed more combat power than large uncoordinated forces.

After the war, the Reichswehr expanded and improved infiltration tactics. The commander in chief, Hans von Seeckt, argued that there had been an excessive focus on encirclement and emphasised speed instead.[28] Seeckt inspired a revision of Bewegungskrieg (maneuver warfare) thinking and its associated Auftragstaktik in which the commander expressed his goals to subordinates and gave them discretion in how to achieve them. The governing principle was "the higher the authority, the more general the orders were"; it was the responsibility of the lower echelons to fill in the details.[29] Implementation of higher orders remained within limits that were determined by the training doctrine of an elite officer corps.[30]

Delegation of authority to local commanders increased the tempo of operations, which had great influence on the success of German armies in the early war period. Seeckt, who believed in the Prussian tradition of mobility, developed the German army into a mobile force and advocated technical advances that would lead to a qualitative improvement of its forces and better coordination between motorized infantry, tanks, and planes.[31]

Britain

The British Army took lessons from the successful infantry and artillery offensives on the Western Front in late 1918. To obtain the best co-operation between all arms, emphasis was placed on detailed planning, rigid control and adherence to orders. Mechanization of the army, as part of a combined-arms theory of war, was considered a means to avoid mass casualties and the indecisive nature of offensives.[32][33] The four editions of Field Service Regulations that were published after 1918 held that only combined-arms operations could create enough fire power to enable mobility on a battlefield. That theory of war also emphasised consolidation and recommended caution against overconfidence and ruthless exploitation.[34]

During the Sinai and Palestine campaign, operations involved some aspects of what would later be called blitzkrieg.[35] The decisive Battle of Megiddo included concentration, surprise and speed. Success depended on attacking only in terrain favouring the movement of large formations around the battlefield and tactical improvements in the British artillery and infantry attack.[36][37] General Edmund Allenby used infantry to attack the strong Ottoman front line in co-operation with supporting artillery, augmented by the guns of two destroyers.[38][39] Through constant pressure by infantry and cavalry, two Ottoman armies in the Judean Hills were kept off-balance and virtually encircled during the Battles of Sharon and Nablus (Battle of Megiddo).[40]

The British methods induced "strategic paralysis" among the Ottomans and led to their rapid and complete collapse.[41] In an advance of 65 ميل (105 km), captures were estimated to be "at least 25٬000 prisoners and 260 guns".[42] Liddell Hart considered that important aspects of the operation had been the extent to which Ottoman commanders were denied intelligence on the British preparations for the attack through British air superiority and air attacks on their headquarters and telephone exchanges, which paralyzed attempts to react to the rapidly-deteriorating situation.[35]

France

Norman Stone detects early blitzkrieg operations in offensives by French Generals Charles Mangin and Marie-Eugène Debeney in 1918.[خ] However, French doctrine in the interwar years became defence-oriented. Colonel Charles de Gaulle advocated concentration of armor and airplanes. His opinions appeared in his 1934 book Vers l'Armée de métier ("Towards the Professional Army"). Like von Seeckt, de Gaulle concluded that France could no longer maintain the huge armies of conscripts and reservists that had fought the First World War, and he sought to use tanks, mechanized forces and aircraft to allow a smaller number of highly trained soldiers to have greater impact in battle. His views endeared him little to the French high command, but, according to historian Henrik Bering, were studied with great interest by Heinz Guderian.[44]

Russia and Soviet Union

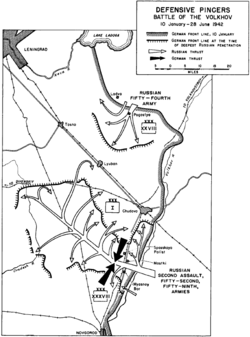

In 1916, General Alexei Brusilov had used surprise and infiltration tactics during the Brusilov Offensive. Later, Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky (1893–1937), Georgii Isserson (1898–1976) and other members of the Red Army developed a concept of deep battle from the experience of the Polish–Soviet War of 1919–1920. Those concepts would guide the Red Army doctrine throughout the Second World War. Realising the limitations of infantry and cavalry, Tukhachevsky advocated mechanized formations and the large-scale industrialisation that they required. Robert Watt (2008) wrote that blitzkrieg has little in common with Soviet deep battle.[45] In 2002, H. P. Willmott had noted that deep battle contained two important differences from blitzkrieg by being a doctrine of total war, not of limited operations, and rejecting decisive battle in favour of several large simultaneous offensives.[46]

The Reichswehr and the Red Army began a secret collaboration in the Soviet Union to evade the Treaty of Versailles occupational agent, the Inter-Allied Commission. In 1926 war games and tests began at Kazan and Lipetsk, in the Soviet Russia. The centers served to field-test aircraft and armored vehicles up to the battalion level and housed aerial- and armoured-warfare schools through which officers rotated.[47]

Nazi Germany

After becoming Chancellor of Germany in 1933, Adolf Hitler ignored the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles. Within the Wehrmacht, which was established in 1935, the command for motorized armored forces was named the Panzerwaffe in 1936. The Luftwaffe, the German air force, was officially established in February 1935, and development began on ground-attack aircraft and doctrines. Hitler strongly supported the new strategy. He read Guderian's 1937 book Achtung – Panzer! and upon observing armored field exercises at Kummersdorf, he remarked, "That is what I want – and that is what I will have".[48][49]

Guderian

Guderian summarized combined-arms tactics as the way to get the mobile and motorized armored divisions to work together and support each other to achieve decisive success. In his 1950 book, Panzer Leader, he wrote:

In this year, 1929, I became convinced that tanks working on their own or in conjunction with infantry could never achieve decisive importance. My historical studies, the exercises carried out in England and our own experience with mock-ups had persuaded me that the tanks would never be able to produce their full effect until the other weapons on whose support they must inevitably rely were brought up to their standard of speed and of cross-country performance. In such formation of all arms, the tanks must play primary role, the other weapons being subordinated to the requirements of the armor. It would be wrong to include tanks in infantry divisions; what was needed were armored divisions which would include all the supporting arms needed to allow the tanks to fight with full effect.[50]

Guderian believed that developments in technology were required to support the theory, especially by equipping armored divisions, tanks foremost, with wireless communications. Guderian insisted in 1933 to the high command that every tank in the German armored force must be equipped with a radio.[51] At the start of World War II, only the German Army was thus prepared with all tanks being "radio-equipped". That proved critical in early tank battles in which German tank commanders exploited the organizational advantage over the Allies that radio communication gave them.

All Allied armies would later copy that innovation. During the Polish campaign, the performance of armored troops, under the influence of Guderian's ideas, won over a number of skeptics who had initially expressed doubt about armored warfare, such as von Rundstedt and Rommel.[52]

Rommel

According to David A. Grossman, by the Twelfth Battle of Isonzo (October–November 1917), while he was conducting a light-infantry operation, Rommel had perfected his maneuver-warfare principles, which were the very same ones that were applied during the blitzkrieg against France in 1940 and were repeated in the Coalition ground offensive against Iraq in the 1991 Gulf War.[53] During the Battle of France and against his staff advisor's advice, Hitler ordered that everything should be completed in a few weeks. Fortunately for the Germans, Rommel and Guderian disobeyed the General Staff's orders (particularly those of General Paul Ludwig Ewald von Kleist) and forged ahead making quicker progress than anyone had expected, on the way "inventing the idea of Blitzkrieg".[54]

It was Rommel who created the new archetype of Blitzkrieg by leading his division far ahead of flanking divisions.[55] MacGregor and Williamson remark that Rommel's version of blitzkrieg displayed a significantly better understanding of combined-arms warfare than that of Guderian.[56] General Hermann Hoth submitted an official report in July 1940 which declared that Rommel had "explored new paths in the command of Panzer divisions".[57]

Methods of operations

Schwerpunkt

Schwerpunktprinzip was a heuristic device (conceptual tool or thinking formula) that was used in the German Army from the nineteenth century to make decisions from tactics to strategy about priority. Schwerpunkt has been translated as center of gravity, crucial, focal point and point of main effort. None of those forms is sufficient to describe the universal importance of the term and the concept of Schwerpunktprinzip. Every unit in the army, from the company to the supreme command, decided on a Schwerpunkt by schwerpunktbildung, as did the support services, which meant that commanders always knew what was the most important and why. The German army was trained to support the Schwerpunkt even when risks had to be taken elsewhere to support the point of main effort and to attack with overwhelming firepower.[58] Schwerpunktbildung allowed the German Army to achieve superiority at the Schwerpunkt, whether attacking or defending, to turn local success at the Schwerpunkt into the progressive disorganisation of the opposing force and to create more opportunities to exploit that advantage even if the Germans were numerically and strategically inferior in general. In the 1930s, Guderian summarized that as Klotzen, nicht kleckern! (roughly "splash, don't spill")[59][60]

Pursuit

Having achieved a breakthrough of the enemy's line, units comprising the Schwerpunkt were not supposed to become decisively engaged with enemy front line units to the right and the left of the breakthrough area. Units pouring through the hole were to drive upon set objectives behind the enemy front line. During the Second World War, German Panzer forces used their motorized mobility to paralyze the opponent's ability to react. Fast-moving mobile forces seized the initiative, exploited weaknesses and acted before the opposing forces could respond. Central to that was the decision cycle (tempo). Through superior mobility and faster decision-making cycles, mobile forces could act faster than the forces opposing them.

Directive control was a fast and flexible method of command. Rather than receiving an explicit order, a commander would be told of his superior's intent and the role that his unit was to fill in that concept. The method of execution was then a matter for the discretion of the subordinate commander. The staff burden was reduced at the top and spread among tiers of command with knowledge about their situation. Delegation and the encouragement of initiative aided implementation, and important decisions could be taken quickly and communicated verbally or with only brief written orders.[61]

Mopping-up

The last part of an offensive operation was the destruction of unsubdued pockets of resistance, which had been enveloped earlier and bypassed by the fast-moving armored and motorized spearheads. The Kesselschlacht ("cauldron battle") was a concentric attack on such pockets. It was there that most losses were inflicted upon the enemy, primarily through the mass capture of prisoners and weapons. During Operation Barbarossa, huge encirclements in 1941 produced nearly 3.5 million Soviet prisoners, along with masses of equipment.[62][د]

Air power

Close air support was provided in the form of the dive bomber and medium bomber, which would support the focal point of attack from the air. German successes are closely related to the extent to which the German Luftwaffe could control the air war in early campaigns in Western and Central Europe and in the Soviet Union. However, the Luftwaffe was a broadly based force with no constricting central doctrine other than its resources should be used generally to support national strategy. It was flexible and could carry out both operational-tactical, and strategic bombing.

Flexibility was the strength of the Luftwaffe in 1939 to 1941. Paradoxically, that became its weakness. While Allied Air Forces were tied to the support of the Army, the Luftwaffe deployed its resources in a more general operational way. It switched from air superiority missions to medium-range interdiction, to strategic strikes to close support duties, depending on the need of the ground forces. In fact, far from it being a specialist panzer spearhead arm, less than 15 percent of the Luftwaffe was intended for close support of the army in 1939.[63]

Stimulants

Methamphetamine use among troops, especially Temmler's 3 mg Pervitin tablets, likely contributed to the Wehrmacht's blitzkrieg success by enabling synchronized, high-endurance operations with minimal rest.[64]

Limitations and countermeasures

Environment

The concepts associated with the term blitzkrieg (deep penetrations by armor, large encirclements, and combined arms attacks) were largely dependent upon terrain and weather conditions. Wherever the ability for rapid movement across "tank country" was not possible, armored penetrations often were avoided or resulted in failure. The terrain would ideally be flat, firm, unobstructed by natural barriers or fortifications, and interspersed with roads and railways. If it were instead hilly, wooded, marshy, or urban, armor would be vulnerable to infantry in close-quarters combat and unable to break out at full speed.[citation needed] Additionally, units could be halted by mud (thawing along the Eastern Front regularly slowed both sides) or extreme snow. Operation Barbarossa helped confirm that armor effectiveness and the requisite aerial support depended on weather and terrain.[65] The disadvantages of terrain could be nullified if surprise was achieved over the enemy by an attack in areas that had been considered natural obstacles, as occurred during the Battle of France in which the main German offensive went through the Ardennes.[66] Since the French thought that the Ardennes unsuitable for massive troop movement, particularly for tanks, the area was left with only light defences, which were quickly overrun by the Wehrmacht. The Germans quickly advanced through the forest and knocked down the trees that the French had thought would impede them.[67]

التفوق الجوي

The influence of air forces over forces on the ground changed significantly over the course of the Second World War. Early German successes were conducted when Allied aircraft could not make a significant impact on the battlefield. In May 1940, there was near parity in numbers of aircraft between the Luftwaffe and the Allies, but the Luftwaffe had been developed to support Germany's ground forces, had liaison officers with the mobile formations and operated a higher number of sorties per aircraft.[68] In addition, the Germans' air parity or superiority allowed the unencumbered movement of ground forces, their unhindered assembly into concentrated attack formations, aerial reconnaissance, aerial resupply of fast moving formations and close air support at the point of attack.[citation needed] The Allied air forces had no close air support aircraft, training or doctrine.[68] The Allies flew 434 French and 160 British sorties a day but methods of attacking ground targets had yet to be developed and so Allied aircraft caused negligible damage. Against the Allies' 600 sorties, the Luftwaffe on average flew 1,500 sorties a day.[69]

On 13 May, Fliegerkorps VIII flew 1,000 sorties in support of the crossing of the Meuse. The following day the Allies made repeated attempts to destroy the German pontoon bridges, but German fighter aircraft, ground fire and Luftwaffe flak batteries with the panzer forces destroyed 56 percent of the attacking Allied aircraft, and the bridges remained intact.[70]

Allied air superiority became a significant hindrance to German operations during the later years of the war. By June 1944, the Western Allies had the complete control of the air over the battlefield, and their fighter-bomber aircraft were very effective at attacking ground forces. On D-Day, the Allies flew 14,500 sorties over the battlefield area alone, not including sorties flown over Northwestern Europe. Against them the Luftwaffe flew some 300 sorties on 6 June. Though German fighter presence over Normandy increased over the next days and weeks, it never approached the numbers that the Allies commanded. Fighter-bomber attacks on German formations made movement during daylight almost impossible.

Subsequently, shortages soon developed in food, fuel and ammunition and severely hampered the German defenders. German vehicle crews and even flak units experienced great difficulty moving during daylight.[ذ] Indeed, the final German offensive operation in the west, Operation Wacht am Rhein, was planned to take place during poor weather to minimise interference by Allied aircraft. Under those conditions, it was difficult for German commanders to employ the "armored idea", if at all.[citation needed]

التكتيكات المضادة

Blitzkrieg is vulnerable to an enemy that is robust enough to weather the shock of the attack and does not panic at the idea of enemy formations in its rear area. That is especially true if the attacking formation lacks the reserve to keep funnelling forces into the spearhead or the mobility to provide infantry, artillery and supplies into the attack. If the defender can hold the shoulders of the breach, it has the opportunity to counter-attack into the flank of the attacker and potentially to cut it off the van, as what happened to Kampfgruppe Peiper in the Ardennes.

During the Battle of France in 1940, the 4th Armoured Division (Major-General Charles de Gaulle) and elements of the 1st Army Tank Brigade (British Expeditionary Force) made probing attacks on the German flank and pushed into the rear of the advancing armored columns at times. That may have been a reason for Hitler to call a halt to the German advance. Those attacks combined with Maxime Weygand's hedgehog tactic would become the major basis for responding to blitzkrieg attacks in the future. Deployment in depth, or permitting enemy or "shoulders" of a penetration, was essential to channelling the enemy attack; artillery, properly employed at the shoulders, could take a heavy toll on attackers. Allied forces in 1940 lacked the experience to develop those strategies successfully, which resulted in the French armistice with heavy losses, but those strategies characterized later Allied operations.

At the Battle of Kursk, the Red Army used a combination of defence in great depth, extensive minefields and tenacious defense of breakthrough shoulders. In that way, they depleted German combat power even as German forces advanced.[citation needed] The reverse can be seen in the Russian summer offensive of 1944, Operation Bagration, which resulted in the destruction of Army Group Center. German attempts to weather the storm and fight out of encirclements failed because of the Soviets' ability to continue to feed armored units into the attack, maintain the mobility and strength of the offensive and arrive in force deep in the rear areas faster than the Germans could regroup.[citation needed]

Logistics

Although effective in quick campaigns against Poland and France, mobile operations could not be sustained by Germany in later years. Strategies based on maneuver have the inherent danger of the attacking force overextending its supply lines and can be defeated by a determined foe who is willing and able to sacrifice territory for time in which to regroup and rearm, as the Soviets did on the Eastern Front, as opposed to, for example, the Dutch, who had no territory to sacrifice. Tank and vehicle production was a constant problem for Germany. Indeed, late in the war, many panzer "divisions" had no more than a few dozen tanks.[72]

As the end of the war approached, Germany also experienced critical shortages in fuel and ammunition stocks as a result of Anglo-American strategic bombing and blockade. Although the production of Luftwaffe fighter aircraft continued, they could not fly because of lack of fuel. What fuel there was went to panzer divisions, and even then, they could not operate normally. Of the Tiger tanks lost against the US Army, nearly half of them were abandoned for lack of fuel.[73]

العمليات العسكرية

بولندا 1939

أوروبا الغربية 1940

الاتحاد السوفياتي الجبهة الشرقية 1941-1944

انظر أيضا

- AirLand Battle, blitzkrieg-like doctrine of US Army in 1980s

- Armored warfare

- Rush (computer and video games), an RTS strategy influenced by the blitzkrieg method

- Shock and Awe, the 21st century American military doctrine

- Vernichtungsgedanken, or 'annihilation thoughts', one of blitzkrieg predecessors

- Mission-type tactics, tactical battle doctrine of delegation and initiative stimulation

- Deep Battle, Soviet Red Army Military Doctrine from the 1930s often confused with blitzkrieg.

- Battleplan (documentary TV series)

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت Frieser 2005, pp. 4–5.

- ^ أ ب Shirer 1969, ch. 29–31.

- ^ Reynolds 2014, p. 254.

- ^ Frieser 2005, p. 34.

- ^ Frieser 2005, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Mercatante 2012, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Frieser 2005, p. 7.

- ^ أ ب Keegan 2005, p. 109.

- ^ Harris 1995, pp. 334–336.

- ^ Griehl 2001, pp. 31, 64–65.

- ^ Frieser 2005, p. 345.

- ^ Holmes et al. 2001, p. 135.

- ^ أ ب ت Harris 1995, p. 337.

- ^ Fanning 1997, pp. 283–287.

- ^ Deist 2003, p. 282.

- ^ Deist 2003, p. 281.

- ^ Harris 1995, pp. 338–339.

- ^ Harris 1995, pp. 337–338.

- ^ Frieser 2005, p. 4.

- ^ Harris 1995, pp. 336–338.

- ^ Frieser 2005, p. 5.

- ^ Domarus 1973, p. 1776.

- ^ Hitler 1942, p. 173.

- ^ Perrett 1983, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Corum 1992, p. 23.

- ^ Corum 1997, p. 37.

- ^ Corum 1992, p. 7.

- ^ Corum 1997, p. 30.

- ^ Citino 2005, p. 152.

- ^ Condell & Zabecki 2008, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Wheeler-Bennett 1980, p. 101.

- ^ French 2000, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Sheffield 2011, p. 121.

- ^ French 2000, pp. 18–20, 22–24.

- ^ أ ب Liddell Hart 1970, pp. 435–438.

- ^ Woodward 2006, p. 191.

- ^ Erickson 2001, p. 200.

- ^ Wavell 1968, p. 206.

- ^ Falls & Becke 1930, pp. 470–1, 480–1, 485.

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Liddell Hart 1970, pp. 435.

- ^ Hughes 2004, pp. 181–183.

- ^ Stone 2008, pp. 170–171.

- ^ De Gaulle 2009.

- ^ Watt 2008, pp. 677–678.

- ^ Willmott 2002, p. 116.

- ^ Edwards 1989, p. 23.

- ^ Guderian 2001, p. 46.

- ^ Edwards 1989, p. 24.

- ^ Guderian 2001, p. 13.

- ^ Guderian 2001, p. 20.

- ^ Murray 2011, p. 129.

- ^ Grossman 1993, pp. 316–335.

- ^ Stroud 2013, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Brighton 2008, p. 247.

- ^ Murray & MacGregor 2001, p. 172.

- ^ Showalter 2006, p. 200.

- ^ Sheldon 2017, pp. vi, 17.

- ^ Frieser 2005, pp. 89–90, 156–157.

- ^ Alexander 2002, p. 227.

- ^ Frieser 2005, pp. 344–346.

- ^ Keegan 1987, p. 265.

- ^ Buckley 1998, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Andreas 2020.

- ^ Winters 2001, pp. 89–96.

- ^ Winters 2001, pp. 47–61.

- ^ Frieser 2005, pp. 137–144.

- ^ أ ب Boyne 2002, p. 233.

- ^ Dildy 2014, p. 36.

- ^ Terraine 1998, pp. 133–135.

- ^ Willmott 1984, pp. 89, 94.

- ^ Simpkin 2000, p. 34.

- ^ Winchester 2002, pp. 18–25.

الهوامش

مراجع

- Chrisp, Peter. (1991) Blitzkrieg!, Witness History Series. New York: Bookwright Press. ISBN 0531183734.

- Citino, Robert Michael. (1999) The Path to Blitzkrieg: Doctrine and Training in the German Army, 1920–1939. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 1555877141.

- Citino, Robert Michael. (2005) The German Way in War: From the Thirty Years War to the Third Reich, University of Kansa Press. ISBN 978-0700661624-4

- Citino, Robert Michael. (2002) Quest for Decisive Victory: From Stalemate to Blitzkrieg in Europe, 1899–1940, Modern War Studies. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0700611762.

- قالب:CondellZabecki2001

- Cooper, Matthew. (1997) The German Army, 1933–1945 : Its Political and Military Failure. Lantham: Scarborough House. ISBN 0812885198.

- Corum, James S. (1992) The Roots of Blitzkrieg: Hans von Seeckt and German Military Reform, Modern War Studies. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 070060541X.

- Corum, James. The Luftwaffe: Creating the Operational Air War, 1918-1940. Kansas University Press. 1997. ISBN 9780700608362

- Alex Danchev, Alchemist of War: The Life of Basil Liddell Hart. Nicolson, London. 1998. ISBN 0-75380-873-0

- Deighton, Len. (1980) Blitzkrieg : From the Rise of Hitler to the Fall of Dunkirk. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0394510208.

- Doughty, Robert A. (1990) The Breaking Point: Sedan and the Fall of France, 1940. Hamden: Archon Books. ISBN 0208022813.

- Erickson, John. (1975) The Road to Stalingrad: Stalin's War Against Germany. London: Cassell 1990 (Reprint). ISBN 0304365416 ISBN 978-0304365418

- Edwards, Roger. (1989) Panzer, a Revolution in Warfare: 1939–1945. London/New York: Arms and Armour. ISBN 0853689326.

- Fanning, William Jr. The Origin of the term "Blitzkrieg": Another view. in the Journal of Military History. Vol. 61, No. 2. April 1997, pp. 283–302.

- Frieser, Karl-Heinz. (1995) Blitzkrieg-Legende : Der Westfeldzug 1940, Operationen des Zweiten Weltkrieges. München: R. Oldenbourg. ISBN 3486561243.

- Frieser, Karl-Heinz, and John T. Greenwood. (2005) The Blitzkrieg Legend: The 1940 Campaign in the West. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1591142946.

- Griehl, Manfred. Junker Ju 87 Stuka. London/Stuttgart: Airlife Publishing/Motorbuch, 2001. ISBN 1-84037-198-6.

- Guderian, Heinz. (1996) Panzer Leader. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306806894.

- Harris, J. P. The Myth of Blitzkrieg in War in History, Volume 2, No. (1995)

- House, Jonathan M. (2001) Combined Arms Warfare in the Twentieth Century, Modern War Studies. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0700610812 | 0700610987

- Keegan, John. (2205) The Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280666-1

- Keegan, John. (1989) The Second World War. (1989) New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0143035738 ISBN 978-0143035732.

- Keegan, John. (1987) The Mask of Command. New York: Viking. ISBN 0140114068 ISBN 978-0140114065.

- Kennedy, Paul, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, Random House, ASIN B000O2NJSO.

- Lewin, Donald. Ultra goes to War; The Secret Story. Hutchinson Publications. 1977. ISBN 0091344204

- Manstein, Erich von, and Anthony G. Powell. (2004) Lost Victories. St. Paul: Zenith Press. ISBN 0760320543.

- Megargee, Geoffrey P. (2000) Inside Hitler's High Command, Modern War Studies. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0700610154.

- Naveh, Shimon (1997). In Pursuit of Military Excellence; The Evolution of Operational Theory. London: Francass. ISBN 0-7146-4727-6.

- Overy, Richard. War and economy in the Third Reich. Oxford University Press. 1995. ISBN 978-0198205999

- Paret, John. Makers of Modern Strategy: From Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age. Oxford University Press. 1986. ISBN 0-19-820097-8

- Powaski, Ronald E. (2003). Lightning War: Blitzkrieg in the West, 1940. John Wiley. ISBN 0471394319, 9780471394310.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Powaski, Ronald E. (2008). Lightning War: Blitzkrieg in the West, 1940. Book Sales, Inc. ISBN 0785820973, 9780785820970.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Shirer, William. (1969) The Collapse of the Third Republic: An Inquiry into the Collapse of France in 1940. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780671203375

- Stolfi, R. H. S. (1991) Hitler's Panzers East: World War II Reinterpreted. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806124008.

- Tooze, Adam, The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy, London: Allen Lane, 2006. ISBN 0-7139-9566-1

- Watt, Robert. "Feeling the Full Force of a Four Point Offensive: Re-Interpreting The Red Army's 1944 Belorussian and L'vov-Przemyśl Operations." The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. ISSN 1351-8046 doi:10.1080/13518040802497564

- Willmott, H.P. When Men Lost Faith in Reason: Reflections on War and Society in the Twentieth Century. Greenwood. 2002. ISBN 978-0275976651

وصلات خارجية

- House, Jonathan M. (1985) Toward Combined Arms Warfare: A Survey of 20th-Century Tactics, Doctrine, and Organization. Fort Leavenworth/Washington: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College.

- Sinesi, Michael Patrick (2001) Modern Bewegungskrieg: German Battle Doctrine, 1920–1940. Thesis submitted to The Faculty of Columbian School of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts; directed by Andrew Zimmerman, Assistant Professor of History. (Microsoft Word document).

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2018

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2015

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2013

- CS1 errors: ISBN

- نظريات عسكرية

- ألمانيا النازية

- مصطلحات نازية

- German loanwords

- استراتيجية عسكرية

- استراتيجيات

- Armoured warfare