حزب المؤتمر الهندي

حزب المؤتمر الهندي Indian National Congress | |

|---|---|

| |

| رئيس الحزب | سونيا غاندي |

| تاريخ التأسيس | 1885 |

| الأيديولوجية | Populism Social liberalism Democratic Socialism Social Democracy |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www.aicc.org.in |

| سياسة الهند | |

حزب المؤتمر الهندي ، هو الحزب الرئيسي في الهند. أسسه Allan Octavian Hume Dadabhai Naoroji, Dinshaw Wacha, Womesh Chandra Bonerjee, Surendranath Banerjee, Monomohun Ghose, and William Wedderburn ، سنة 1885 ، أصبح حزب المؤتمر هو الحزب الرائد في حركة استقلال الهند، بعضوية أكثر من 15 مليون مشارك في مواجهة الحكم البريطاني في الهند.

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British Empire in Asia and Africa.[أ][1] From the late 19th century, and especially after 1920, under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, the Congress became the principal leader of the Indian independence movement.[2] The Congress led India to independence from the United Kingdom,[ب][3][ت][4] and significantly influenced other anti-colonial nationalist movements in the British Empire.[ث][1]

The INC is a "big tent" party that has been described as sitting on the centre of the Indian political spectrum.[5][6][7] The party held its first session in 1885 in Bombay where W.C. Bonnerjee presided over it.[8] After Indian independence in 1947, Congress emerged as a catch-all, Indian nationalist and secular party, dominating Indian politics for the next 50 years. The party's first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, led the Congress to support socialist policies by creating the Planning Commission, introducing Five-Year Plans, implementing a mixed economy, and establishing a secular state. After Nehru's death and the short tenure of Lal Bahadur Shastri, Indira Gandhi became the leader of the party. In the 17 general elections since independence, it has won an outright majority on seven occasions and has led the ruling coalition a further three times, heading the central government for more than 54 years. There have been six prime ministers from the Congress party, the first being Jawaharlal Nehru (1947–1964), and the most recent being Manmohan Singh (2004–2014). Since the 1990s, the Bharatiya Janata Party has emerged as the main rival of the Congress in both national and regional politics.

In 1969, the party suffered a major split, with a faction led by Indira Gandhi leaving to form the Congress (R), with the remainder becoming the Congress (O). The Congress (R) became the dominant faction, winning the 1971 general election by a huge margin. From 1975 to 1977, Indira Gandhi declared a state of emergency in India, resulting in widespread oppression and abuses of power. Another split in the party occurred in 1979, leading to the creation of the Congress (I), which was recognized as the Congress by the Election Commission in 1981. Under Rajiv Gandhi's leadership, the party won a massive victory in the 1984 general elections, nevertheless losing the election held in 1989 to the National Front. The Congress then returned to power under P. V. Narasimha Rao, who moved the party towards an economically liberal agenda, a sharp break from previous leaders. However, it lost the 1996 general election and was replaced in government by the National Front. After a record eight years out of office, the Congress-led coalition known as the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) under Manmohan Singh formed a government after the 2004 general elections. Subsequently, the UPA again formed the government after winning the 2009 general elections, and Singh became the first prime minister since Indira Gandhi in 1971 to be re-elected after completing a full five-year term. However, under the leadership of Rahul Gandhi in the 2014 general election, the Congress suffered a heavy defeat, winning only 44 seats of the 543-member Lok Sabha (the lower house of the Parliament of India). In the 2019 general election, the party failed to make any substantial gains and won 52 seats, failing to form the official opposition yet again. In the 2024 general election, the party performed better-than-expected, and won 99 seats, forming the official opposition with their highest seat count in a decade.[9][10]

On social issues, it advocates secular policies that encourage equal opportunity, right to health, right to education, civil liberty, and support social market economy, and a strong welfare state. Being a centrist party, its policies predominantly reflected balanced positions including secularism, egalitarianism, and social stratification. The INC supports contemporary economic reforms such as liberalisation, privatisation and globalization. A total of 61 people have served as the president of the INC since its formation. Sonia Gandhi is the longest-serving president of the party, having held office for over twenty years from 1998 to 2017 and again from 2019 to 2022 (as interim). Mallikarjun Kharge is the current party president. The district party is the smallest functional unit of Congress. There is also a Pradesh Congress Committee (PCC), present at the state level in every state. Together, the delegates from the districts and PCCs form the All India Congress Committee (AICC). The party is additionally structured into various committees and segments including the Working Committee (CWC), Seva Dal, Indian Youth Congress (IYC), Indian National Trade Union Congress (INTUC), and National Students' Union of India (NSUI). The party holds the annual plenary sessions, at which senior Congress figures promote party policy.

التاريخ

عهد ما قبل الاستقلال

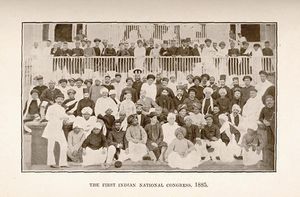

During the latter part of the 1870s, there were concerted efforts among Indians to establish a pan-Indian organization for nationalist political influence.[11] In 1883, Allan Octavian Hume, a retired British Civil Servant also known for his pro-Indian activities, outlined his idea for a body representing Indian interests in an open letter to graduates of the University of Calcutta.[11] The aim was to obtain a greater share in government for educated Indians and to create a platform for civic and political dialogue between them and the British Raj. Hume initiated contact with prominent leaders in India and a notice convening the first meeting of the Indian National Union to be held in Poona the following December, was issued.[12] However, due to a cholera outbreak in Poona it was moved to Bombay.[13][14] Subsequently, the first session of the Indian National Congress held in Bombay from 28 to 31 December 1885 at Gokuldas Tejpal Sanskrit College.[15] Hume organised the first meeting in Bombay with the approval of the Viceroy Lord Dufferin. He assumed office as the General Secretary, while Umesh Chandra Banerjee was appointed as the first president of Congress.[16] Hume believed that while the British helped bring peace to India, they still had not solved the country’s economic problems.[17]

The first session was attended by 72 delegates, with the majority being lawyers, representing each province of India.[18][19] Notable representatives included Scottish ICS officer William Wedderburn, Dadabhai Naoroji, Badruddin Tyabji and Pherozeshah Mehta of the Bombay Presidency Association, Ganesh Vasudeo Joshi of the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, social reformer and newspaper editor Gopal Ganesh Agarkar, Justice K. T. Telang, N. G. Chandavarkar, Dinshaw Wacha, Behramji Malabari, journalist, and activist Gooty Kesava Pillai, and P. Rangaiah Naidu of the Madras Mahajana Sabha.[20][21] Notably, there were no women present at this session.[16] During the first session, the Indian delegates presented 9 resolutions to the British authorities including; India Council in London should be abolished, creation of legislative councils for the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP), Sindh and Awadh, Civil Services Reform, and Appointment of a commission to enquire into the working of the Indian Administration from 1858- till date.[22]

In its early years, Congress was an assembly for politically active individuals who sought reforms within the British Empire. However, there were two distinct factions within the party. One group was in favor of seeking complete independence from British rule, while the other aimed to bring about reforms within the existing system, with a focus on Indianisation. This division marked the early phase of Congress, as different leaders and members had varied visions for the future of India, ranging from moderate reforms to a push for full sovereignty.[23] They primarily advocated for the 'Indianisation' of administrative services, emphasizing that India should be governed by Indians, with British collaboration. The majority of the founding members of Congress has been educated or lived in Britain. As a result, unrepresentative of the Indian masses at the time,[24] it functioned more as a stage for elite Indian ambitions than a political party for the first two decade of its existence.[25]

Early years

Since its establishment, the Congress was led by Moderate leaders, who were influenced by Western political ideas, particularly liberalism. They emphasized individual dignity, the right to freedom, and equality for all, regardless of caste, creed, or sex. This philosophy guided them in opposing British autocracy, demanding the rule of law, equality before the law, and advocating for secularism.[26] However, by 1905, two factions had emerged within the party, leading to different approaches and ideologies regarding the methods to achieve self-rule for India. A division arose between the Moderates, led by Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who believed in a peaceful and constitutional approach to achieve reforms and self-governance within the framework of the British Empire, and the Extremists.[27] The moderates preferred to avoid direct conflict with the Britishers, aiming instead to reform their governance to better serve the country's interests. They aimed to collaborate with British authorities and use constitutional means, such as petitions, resolutions, and dialogue, to address the grievances of Indians.[26] Over time, as they recognized the impact of British rule, many moderate leaders shifted their stance and started advocating for Swaraj or self-government for India within the British Empire. Thereafter, the moderates followed a two-fold approach to achieve their goals. First, they aimed to build strong public opinion to inspire a sense of national consciousness and unity, while educating the masses on shared political issues. Second, they sought to influence both the British government and public opinion, advocating for reforms in India that aligned with the demands of the nationalists.[26] In 1889, a British branch of the Indian National Congress was set up in London.[28] Dadabhai Naoroji, a member of the sister Indian National Association, was elected president of the Congress in 1886. He was the first Indian Member of Parliament in the British House of Commons (1892–1895) and spent a large part of his life and resources campaigning for India’s cause on the international stage. The Moderates were able to analyze the political and economic impacts of British rule in India. Dadabhai Naoroji, Romesh Chunder Dutt, and Dinshaw Wacha and others introduced the Drain Theory to highlight how Britain exploited India's resources.[29] The Drain Theory, proposed by these leaders, challenged the notion that British rule was beneficial for India, shaping a nationwide public opinion that British colonialism was the primary reason for India’s poverty and economic exploitation.[30] The moderate leaders had several demands, including proper representation of Indians on the Legislative Councils and an increase in the powers of these councils. They also advocated for administrative reforms and voiced their opinions on international issues. They opposed the annexation of Burma, the military actions in Afghanistan, and the treatment of tribal people in northwestern India. Additionally, they called for better conditions for Indian workers who had migrated to countries such as South Africa, Malaya, Mauritius, the West Indies, and British Guyana.

The other faction led by extremist or radical leaders, including Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Bipin Chandra Pal, and Lala Lajpat Rai, colloquially, "Lal, Bal, Pal", was more radical in their approach. Emerging as a result of the partition of Bengal in 1905, the extremist group believed in direct action and criticized the moderate approach, advocating for more assertive and aggressive means to achieve self-rule (Swaraj). They were less willing to compromise with the British and focused on building mass support, instilling in them a sense of self-respect, self-reliance, pride in their ancient heritage and national unity to attain their objectives.[31] The Extremist leaders opposed the use of violence against British rule and did not condone methods such as political murder and assassination. They successfully engaged the urban middle and lower classes, as well as mobilized peasants and workers. The Extremist leaders utilized religious symbols to inspire the masses, but they did not intertwine religion with politics. Tilak tried to mobilise Hindu Indians by appealing to an explicitly Hindu political identity displayed in the annual public Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav and Shiv Jayanti festivals that he inaugurated in western India.[32] Tilak, along with his friend Gopal Ganesh Agarkar, believed that educating the people was the best way to serve the country. In 1876, they founded the New English School in Pune.[33] However, Tilak soon realized that education alone was not sufficient; the people also needed to be aware of the country's condition. To achieve this, he started two weekly publications in 1881: the Maratha in English and Kesari in Marathi. By the end of 1905, Congress was transformed into a mass movement during the partition of Bengal, and the resultant Swadeshi movement.[21] However, the ideological differences between the extremists and moderates led to a deep divide. During its session held in Surat in December 1907, a split occurred between two factions within the Congress known as Surat Split.[34]

Annie Besant, a British social reformer, moved to India in 1893 and became actively involved in the Congress.[35] Recognizing the importance of full cooperation from the extremists for the success of the movement, both Tilak and Besant realized that it was necessary to secure the full cooperation of the moderates. In 1915, during the annual session of the Congress held at Lucknow under the presidency of Ambica Charan Mazumdar, it was decided that the extremists led by Tilak would be admitted to the Congress. Inspired by the Irish Home Rule movement, which sought greater autonomy from Britain, Tilak and Besant were influenced by the concept of self-government (Home Rule) and began calling for similar rights for India.[36] However, Tilak and Besant were unable to convince the Indian National Congress to support their proposal to set up Home Rule leagues. As a result, they established separate leagues. Tilak launched the Indian Home Rule League in April 1916 at Belgaum, with its headquarters in Poona. His league operated primarily in Maharashtra (excluding Bombay), Karnataka, and the Central Provinces and Berar.[36] In contrast, Besant set up her All-India Home Rule League in September 1916 in Madras, which grew to include over 200 branches across the country.[35] Prominent leaders who joined or supported the Home Rule movement included Motilal Nehru, Bhulabhai Desai, Jawaharlal Nehru, Chittaranjan Das, Kanaiyalal Maneklal Munshi, Saifuddin Kitchlew, Madan Mohan Malviya, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Tej Bahadur Sapru, and Lala Lajpat Rai.

Congress as a mass movement

In 1915, Mahatma Gandhi returned from South Africa and joined Congress.[37][38] His efforts in South Africa were well known not only among the educated but also among the masses. During 1917 and 1918, Mahatma Gandhi was involved in three struggles– known as Champaran Satyagraha, Ahmedabad Mill Strike and Kheda Satyagraha.[39][40][41] After World War I, the party came to be associated with Gandhi, who remained its unofficial spiritual leader and icon.[42] He formed an alliance with the Khilafat Movement in 1920 as part of his opposition to British rule in India,[43] and fought for the rights for Indians using civil disobedience or Satyagraha as the tool for agitation.[44] In 1922, after the deaths of policemen at Chauri Chaura, Gandhi suspended the agitation.

With the help of the moderate group led by Gokhale, in 1924 Gandhi became president of Congress.[45][46] The rise of Gandhi's popularity and his satyagraha art of revolution led to support from Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Rajendra Prasad, Khan Mohammad Abbas Khan, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Chakravarti Rajgopalachari, Anugrah Narayan Sinha, Jayaprakash Narayan, Jivatram Kripalani, and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad. As a result of prevailing nationalism, Gandhi's popularity, and the party's attempts at eradicating caste differences, untouchability, poverty, and religious and ethnic divisions, Congress became a forceful and dominant group.[47][48][49] Although its members were predominantly Hindu, it had members from other religions, economic classes, and ethnic and linguistic groups.[50]

At the Congress 1929 Lahore session under the presidency of Jawaharlal Nehru, Purna Swaraj (complete independence) was declared as the party's goal, declaring 26 January 1930 as Purna Swaraj Diwas (Independence Day).[51] The same year, Srinivas Iyenger was expelled from the party for demanding full independence, not just home rule as demanded by Gandhi.[52]

After the passage of the Government of India Act 1935, provincial elections were held in India in the winter of 1936–37 in eleven provinces: Madras, Central Provinces, Bihar, Orissa, United Provinces, Bombay Presidency, Assam, NWFP, Bengal, Punjab, and Sindh. The final results of the elections were declared in February 1937.[53] The Indian National Congress gained power in eight of them – the three exceptions being Bengal, Punjab, and Sindh.[53] The All-India Muslim League failed to form a Government in any Province.[54]

Congress Ministers resigned in October and November 1939 in protest against Viceroy Lord Linlithgow's declaration that India was a belligerent in World War II without consulting the Indian people.[55] In 1939, Subhas Chandra Bose, the elected president of Congress in 1938 and 1939, resigned from Congress over the selection of the working committee.[56] Congress was an umbrella organisation, sheltering radical socialists, traditionalists, and Hindu and Muslim conservatives. Mahatma Gandhi expelled all the socialist groupings, including the Congress Socialist Party, the Krishak Praja Party, and the Swaraj Party, along with Subhas Chandra Bose, in 1939.[42]

After the failure of the Cripps Mission launched by the British government to gain Indian support for the British war effort, Mahatma Gandhi made a call to "Do or Die", delivered in Bombay on 8 August 1942 at the Gowalia Tank Maidan. Gandhi endorsed the Quit India movement, opposing any help to the British cause in the Second World War.[57] The colonial government instituted mass arrests including of Gandhi and Congress leaders, and killed over 1,000 Indians who participated in this movement.[58] Meanwhile, a spate of violent attacks were carried out by the nationalists against the colonial government and infrastructure.[59] The movement played a role in weakening British control over the South Asian region and ultimately paved the way for Indian independence.[59][60]

In 1945, when the Second World War almost came to an end, the Labour Party of the United Kingdom won elections with a promise to provide independence to India.[61][62] The jailed political prisoners of the Quit India movement were released in the same year.[63]

In 1946, the colonial government tried the soldiers of Japanese-sponsored Indian National Army in the INA trials. In response, Congress helped form the INA Defence Committee, which assembled a legal team to defend the soldiers of the Azad Hind provisional government. The team included several famous lawyers, including Bhulabhai Desai, Asaf Ali, and Jawaharlal Nehru.[64] The colonial government eventually backtracked in the face of opposition by the Congress.[65][66]

رؤساء وزراء هنديون من حزب المؤتمر

- جواهر لال نهرو (1947 - 1964)

- Gulzarilal Nanda (May - June 1964, January 1966)

- Lal Bahadur Shastri (1964 - 1966)

- إنديرا غاندي (1966 - 1977, 1980 - 1984)

- راجيف غاندي (1984 - 1989)

- P.V. Narasimha Rao (1991 - 1996)

- Manmohan Singh (2004 - 2009)

- Manmohan Singh (2009- Present]]

الجدل والانتقادات

تكوين الحكومة الهندية الحالية

السياسات والبرامج

السياسة الاجتماعية

السياسة الاقتصادية

السياسة الخارجية

التنظيم الداخلي

المؤتمر في مختلف الولايات

قائمة رؤساء الحزب الحاليون

- Y.S. Rajasekhara Reddy - Andhra Pradesh

- Dorjee Khandu - Arunachal Pradesh

- Tarun Gogoi - Assam

- Sheila Dikshit - Delhi

- Digambar Kamat - Goa

- Bhupinder Singh Hooda - Haryana

- Ashok Chavan - Maharashtra

- Okram Ibobi Singh - Manipur

- Pu Lalthanhawla - Mizoram

- Vaithilingam - Pondicherry

- Ashok Gehlot - Rajasthan

قائمة رؤساء الحزب

| اسم الرئيس | Life Span | سنة الرئاسة | مكان المؤتمر |

|---|---|---|---|

| Womesh Chandra Bonnerjee | December 29, 1844- 1906 | 1885 | Bombay |

| Dadabhai Naoroji | September 4, 1825- 1917 | 1886 | Calcutta |

| Badruddin Tyabji | October 10, 1844- 1906 | 1887 | Madras |

| George Yule | 1829- 1892 | 1888 | Allahabad |

| Sir William Wedderburn | 1838- 1918 | 1889 | Bombay |

| Sir Pherozeshah Mehta | August 4, 1845- 1915 | 1890 | Calcutta |

| P. Anandacharlu | August 1843- 1908 | 1891 | Nagpur |

| Womesh Chandra Bonnerjee | December 29, 1844- 1906 | 1892 | Allahabad |

| Dadabhai Naoroji | September 4, 1848- 1925 | 1893 | Lahore |

| Alfred Webb | 1834- 1908 | 1894 | Madras |

| Surendranath Banerjea | November 10, 1848- 1925 | 1895 | Poona |

| Rahimtulla M. Sayani | April 5, 1847- 1902 | 1896 | Calcutta |

| Sir C. Sankaran Nair | July 11, 1857- 1934 | 1897 | Amraoti |

| Ananda Mohan Bose | September 23, 1847- 1906 | 1898 | Madras |

| Romesh Chunder Dutt | August 13, 1848- 1909 | 1899 | Lucknow |

| Sir Narayan Ganesh Chandavarkar | December 2, 1855- 1923 | 1900 | Lahore |

| Sir Dinshaw Edulji Wacha | August 2, 1844- 1936 | 1901 | Calcutta |

| Surendranath Banerjea | November 10, 1825- 1917 | 1902 | Ahmedabad |

| Lalmohan Ghosh | 1848- 1909 | 1903 | Madras |

| Sir Henry Cotton | 1845- 1915 | 1904 | Bombay |

| Gopal Krishna Gokhale | May 9, 1866- 1915 | 1905 | Benares |

| Dadabhai Naoroji | September 4, 1825- 1917 | 1906 | Calcutta |

| Rashbihari Ghosh | December 23, 1845- 1921 | 1907 | Surat |

| Rashbihari Ghosh | December 23, 1845- 1921 | 1908 | Madras |

| Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya | December 25, 1861- 1946 | 1909 | Lahore |

| Sir William Wedderburn | 1838- 1918 | 1910 | Allahabad |

| Pandit Bishan Narayan Dar | 1864- 1916 | 1911 | Calcutta |

| Rao Bahadur Raghunath Narasinha Mudholkar | 1857- 1921 | 1912 | Bankipur |

| Nawab Syed Muhammad Bahadur | ?- 1919 | 1913 | Karachi |

| Bhupendra Nath Bose | 1859- 1924 | 1914 | Madras |

| Lord Satyendra Prasanna Sinha | March 1863- 1928 | 1915 | Bombay |

| Ambica Charan Mazumdar | 1850- 1922 | 1916 | Lucknow |

| Annie Besant | October 1, 1847- 1933 | 1917 | Calcutta |

| Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya | December 25, 1861- 1946 | 1918 | Delhi |

| Syed Hasan Imam | August 31, 1871- 1933 | 1918 | Bombay (Special Session) |

| Pandit Motilal Nehru | May 6, 1861- February 6, 1931 | 1919 | Amritsar |

| Lala Lajpat Rai | January 28, 1865- November 17, 1928 | 1920 | Calcutta (Special Session) |

| C. Vijayaraghavachariar | 1852- April 19, 1944 | 1920 | Nagpur |

| Hakim Ajmal Khan | 1863- December 29, 1927 | 1921 | Ahmedabad |

| Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das | November 5, 1870- June 16, 1925 | 1922 | Gaya |

| Maulana Mohammad Ali | December 10, 1878- January 4, 1931 | 1923 | Kakinada |

| Maulana Abul Kalam Azad | 1888- February 22, 1958 | 1923 | Delhi (Special Session) |

| Mahatma Gandhi | October 2, 1869- January 30, 1948 | 1924 | Belgaum |

| Sarojini Naidu | February 13, 1879- March 2, 1949 | 1925 | Kanpur |

| S. Srinivasa Iyengar | September 11, 1874- May 19, 1941 | 1926 | Gauhati |

| Dr. M A Ansari | December 25, 1880- May 10, 1936 | 1927 | Madras |

| Pandit Motilal Nehru | May 6, 1861- February 6, 1931 | 1928 | Calcutta |

| Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru | November 14, 1889- May 27, 1964 | 1929 & 30 | Lahore |

| Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel | October 31, 1875- December 15, 1950 | 1931 | Karachi |

| Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya | December 25, 1861- 1946 | 1932 | Delhi |

| Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya | December 25, 1861- 1946 | 1933 | Calcutta |

| Nellie Sengupta | 1886- 1973 | 1933 | Calcutta |

| Dr. Rajendra Prasad | December 3, 1884- February 28, 1963 | 1934 & 35 | Bombay |

| Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru | November 14, 1889- May 27, 1964 | 1936 | Lucknow |

| Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru | November 14, 1889- May 27, 1964 | 1936& 37 | Faizpur |

| Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose | January 23, 1897- August 18, 1945? | 1938 | Haripura |

| Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose | January 23, 1897- August 18, 1945? | 1939 | Tripuri |

| Maulana Abul Kalam Azad | 1888- February 22, 1958 | 1940-46 | Ramgarh |

| Acharya J.B. Kripalani | 1888- March 19, 1982 | 1947 | Delhi |

| Dr Pattabhi Sitaraimayya | December 24, 1880- December 17, 1959 | 1948 & 49 | Jaipur |

| Purushottam Das Tandon | August 1, 1882- July 1, 1961 | 1950 | Nasik |

| Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru | November 14, 1889- May 27, 1964 | 1951 & 52 | Delhi |

| Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru | November 14, 1889- May 27, 1964 | 1953 | Hyderabad |

| Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru | November 14, 1889- May 27, 1964 | 1954 | Calcutta |

| U N Dhebar | September 21, 1905- 1977 | 1955 | Avadi |

| U N Dhebar | September 21, 1905- 1977 | 1956 | Amritsar |

| U N Dhebar | September 21, 1905- 1977 | 1957 | Indore |

| U N Dhebar | September 21, 1905- 1977 | 1958 | Gauhati |

| U N Dhebar | September 21, 1905- 1977 | 1959 | Nagpur |

| Indira Gandhi | November 19, 1917- October 31, 1984 | 1959 | Delhi |

| Neelam Sanjiva Reddy | May 19, 1913- June 1, 1996 | 1960 | Bangalore |

| Neelam Sanjiva Reddy | May 19, 1913- June 1, 1996 | 1961 | Bhavnagar |

| Neelam Sanjiva Reddy | May 19, 1913- June 1, 1996 | 1962 & 63 | Patna |

| K. Kamaraj | July 15, 1903- October 2, 1975 | 1964 | Bhubaneswar |

| K. Kamaraj | July 15, 1903- October 2, 1975 | 1965 | Durgapur |

| K. Kamaraj | July 15, 1903- October 2, 1975 | 1966 & 67 | Jaipur |

| S. Nijalingappa | December 10, 1902- August 9, 2000 | 1968 | Hyderabad |

| S. Nijalingappa | December 10, 1902- August 9, 2000 | 1969 | Faridabad |

| Jagjivan Ram | April 5, 1908- July 6, 1986 | 1970 & 71 | Bombay |

| Dr Shankar Dayal Sharma | August 19, 1918- December 26, 1999 | 1972- 74 | Calcutta |

| Dev Kant Baruah | February 22, 1914- 1996 | 1975- 77 | Chandigarh |

| إنديرا غاندي | November 19, 1917- October 31, 1984 | 1978- 83 | Delhi |

| إنديرا غاندي | November 19, 1917- October 31, 1984 | 1983 -84 | Calcutta |

| راجيف غاندي | August 20, 1944- May 21, 1991 | 1985 -91 | Bombay |

| P. V. Narasimha Rao | June 28, 1921- December 23, 2004 | 1992 -96 | Tirupati |

| Sitaram Kesri | November 1919- October 24, 2000 | 1997 -98 | Kolkata |

| سونيا غاندي | 9 ديسمبر, 1946- | 1998-الآن (2009) | كلكتا |

الانتخابات العامة 2009

الحزب المحافظ في الولايات

انظر أيضا

- Statewise Election history of Congress Party

- Jinnah's People's Memorial Hall

- عائلة نهرو غاندي

- قائمة الأحزاب السياسية في الهند

- سياسة الهند

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت ث Marshall, P. J. (2001), The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire, Cambridge University Press, p. 179, ISBN 978-0-521-00254-7, https://books.google.com/books?id=S2EXN8JTwAEC&pg=PAPA179

- ^ "Information about the Indian National Congress". open.ac.uk. Arts & Humanities Research council. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ أ ب Chiriyankandath, James (2016), Parties and Political Change in South Asia, Routledge, p. 2, ISBN 978-1-317-58620-3, https://books.google.com/books?id=c4n7CwAAQBAJ&pg=PAPA2

- ^ أ ب Kopstein, Jeffrey; Lichbach, Mark; Hanson, Stephen E. (2014), Comparative Politics: Interests, Identities, and Institutions in a Changing Global Order, Cambridge University Press, p. 344, ISBN 978-1-139-99138-4, https://books.google.com/books?id=L2jwAwAAQBAJ&pg=PAPA344

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBarrington2009 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةcentrist - ^ Saez, Lawrence; Sinha, Aseema (2010). "Political cycles, political institutions and public expenditure in India, 1980–2000". British Journal of Political Science. 40 (1): 91–113. doi:10.1017/s0007123409990226. ISSN 0007-1234. S2CID 154767259.

- ^ "Indian National Congress". Indian National Congress. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ Joy, Shemin. "Lok Sabha Elections 2024: With support of 3 Independent MPs, I.N.D.I.A now has 237 seats". Deccan Herald.

- ^ Roushan, Anurag (9 July 2024). "Rahul Gandhi to visit Rae Bareli today to thank people of constituency for his Lok Sabha election victory". India TV News.

- ^ أ ب Gehlot, N.S. (1991). The Congress Party in India: Policies, Culture, Performance. Deep & Deep Publications. p. 35. ISBN 978-81-7100-306-8.

The activities of Mr. A.O. Hume were pro – Indian and full of patriotic spirit for the youths.

- ^ Sitaramayya, B. Pattabhi. 1935. The History of the Indian National Congress. Working Committee of the Congress. Scanned version

- ^ "Full text of 'The History of the Indian National Congress'". The Working Committee of the Congress Madras. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ Pattabhi Sita Ramaiah (1 November 2018). "The History of the Indian National Congress (1885–1935)" – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Chapter Four Indian National Congress". The Nehrus: Motilal and Jawaharlal: With a New Preface. Oxford Academic. 6 December 2007. p. 45. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195693430.003.0004. ISBN 978-0-19-569343-0. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ أ ب "Indian National Movement with Special Reference to Surendranath Banerjea and Lajpat Rai" (PDF). Retrieved 29 November 2024.

- ^ "Chapter Four Indian National Congress". Four Chapter Four Indian National Congress. Oxford University Press. 6 December 2007. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195693430.003.0004. ISBN 978-0-19-569343-0. Retrieved 29 November 2024.

- ^ Singh, Kanishka (5 December 2017). "Indian National Congress: From 1885 till 2017, a brief history of past presidents". The Indian Express. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Sonia sings Vande Mataram at Congress function – Rediff.com India News". Rediff.com. 28 December 2006. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ Sitaramayya, B. Pattabhi (1935). The history of the Indian National Congress (1885–1935). Working Committee of the Congress. pp. 12–27.

- ^ أ ب Walsh, Judith E. (2006). A Brief History of India. Infobase Publishing. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-4381-0825-4.

- ^ Moore, R. J. (1969). "Daniel Argov: Moderates and extremists in the Indian nationalist movement,1883–1920, with special reference to Surendranath Banerjea and Lajpat Raj. xix, 246 pp., 2 Plates. london: Asia Publishing House, [1968]. 45s". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. Cambridge University Press (CUP). 32 (1): 230. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00094507. ISSN 0041-977X.

- ^ "Indian National Congress". The Open University. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Richard Sisson; Stanley A. Wolpert (1988). Congress and Indian Nationalism: The Pre-independence Phase. University of California Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-520-06041-8.

Those fewer than 100 English-educated gentlemen of means and property, mostly lawyers and journalists, could hardly claim to 'represent' some 250 million illiterate impoverished peasants

- ^ Richard Sisson; Stanley A. Wolpert (1988). Congress and Indian Nationalism: The Pre-independence Phase. University of California Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-520-06041-8.

Without any funds or any secretariat, however (other than Hume) Congress remained, during its first decade at least, more of a sounding board for elite Indian aspirations than a political party.

- ^ أ ب ت "MODERATES, EXTREMISTS AND REVOLUTIONARIES" (PDF). eGyanKosh, IGNOU. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ "The Making of the National Movement: 1870s–1947" (PDF). National Council of Educational Research and Training. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ Shankar, Prabha Ravi (2004). "BRITISH COMMITTEE OF THE INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS — A CRITICAL APPRAISAL". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Indian History Congress. 65: 761–767. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44144789. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ "Uncivil liberalism: labour, capital and commercial society in Dadabhai Naoroji's political thought". search.worldcat.org. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ VISANA, VIKRAM (12 January 2016). "Vernacular Liberalism, Capitalism, and Anti-Imperialism in the Political Thought of Dadabhai Naoroji". The Historical Journal. Cambridge University Press (CUP). 59 (3): 775–797. doi:10.1017/s0018246x15000230. ISSN 0018-246X.

- ^ "Moderates, Extremists and Revolutionaries" (PDF). Indira Gandhi National Open University. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ Stanley A. Wolpert, Tilak and Gokhale: Revolution and Reform in the Making of Modern India (1962) p 67

- ^ Banerjee, Shoumojit (30 May 2018). "Pune school founded by Bal Gangadhar Tilak goes co-ed once more". The Hindu.

- ^ "Surat Split, 1907 – History, Causes, Aftermath & Impact" (PDF). eGyanKosh, IGNOU. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ أ ب "Annie Besant". BBC. 30 October 2006. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ أ ب "Establishment of Tilak's Home Rule League". Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ Field, J.F. (2019). Great Speeches in Minutes. Quercus. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-78747-722-3. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ^ "Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi". South African History Online. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand (1 February 1931). My experiments with truth. Ahmedabad: Sarvodaya.

- ^ Sarkar, Sumit (2014). Modern India 1886–1947. Pearson Education India. ISBN 9789332540859.

- ^ Patel, Sujata (1984). "Class Conflict and Workers' Movement in Ahmedabad Textile Industry, 1918–23". Economic and Political Weekly. 19 (20/21): 853–864. JSTOR 4373280. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ أ ب Mahatma Gandhi (1994). The Gandhi Reader: A Sourcebook of His Life and Writings. Grove Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-8021-3161-4.

- ^ Carl Olson (2007). The Many Colors of Hinduism: A Thematic-historical Introduction. Rutgers University Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780813540689.

- ^ Gail Minault, The Khilafat movement p 69

- ^ "Gopal Krishna Gokhale: The liberal nationalist regarded by Gandhi as his political guru". 13 May 2021.

- ^ "Indian National Congress: From 1885 till 2017, a brief history of past presidents". 5 December 2017.

- ^ Mittal, S. K.; Habib, Irfan (1982). "The Congress and the Revolutionaries in the 1920s". Social Scientist. 10 (6): 20–37. doi:10.2307/3517065. JSTOR 3517065.

- ^ Iodice, Emilio (2017). "The Courage to Lead of Gandhi". The Journal of Values-Based Leadership. 10 (2). doi:10.22543/0733.102.1192.

- ^ "Gandhiji – an inspiration". The Hindu. 1 October 2012.

- ^ Chandra, A.M. (2008). India Condensed: 5,000 Years of History & Culture. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. p. 66. ISBN 978-981-261-975-4.

- ^ "Declaration of Purna Swaraj (Indian National Congress, 1930) Clipboard". CAD India. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "Main Bharat Hun". Main Bharat Hun. Archived from the original on 21 July 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ أ ب Rohit Manglik (21 May 2020). SSC Sub Inspector CPO (Tier I and II) 2020. EduGorilla. p. 639. GGKEY:AWW79B82A9H.

- ^ S. M. Ikram (1995). Indian Muslims and Partition of India. Atlantic Publishers. p. 240. ISBN 9788171563746.

- ^ SN Sen (2006). History Modern India. New Age International. p. 202. ISBN 9788122417746.

- ^ "Subhas Chandra Bose". Open.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

Dates of time spent in Britain: 1919–21

- ^ Green, J.; Della-Rovere, C. (2014). Gandhi and the Quit India Movement. Days of Decision. Pearson Education Limited. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-4062-6156-1.

- ^ Marques, J. (2020). The Routledge Companion to Inclusive Leadership. Routledge Companions in Business, Management and Marketing. Taylor & Francis. pp. 309–310. ISBN 978-1-000-03965-8.

- ^ أ ب Anderson, D.; Killingray, D. (1992). Policing and Decolonisation: Politics, Nationalism, and the Police, 1917–65. Studies in imperialism. Manchester University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-7190-3033-8.

Britain's hold over India weakened and an early resumption of Congress rule appeared inevitable

- ^ Arthur Herman (2008). Gandhi & Churchill: The Epic Rivalry that Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Age. Random House. pp. 467–70. ISBN 978-0-553-90504-5. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014.

- ^ Studlar, D.T. (2018). Great Britain: Decline Or Renewal?. Taylor & Francis. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-429-96865-5.

The Labour Party promised independence for India in its campaign in the general election of 1945.

- ^ Ram, J. (1997). V.K. Krishna Menon: A Personal Memoir. Oxford University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-19-564228-5.

Labour Party had promised freedom for India if they came to power

- ^ Naveen Sharma (1990). Right to Property in India. Deep & Deep Publications. p. 36.

- ^ "Lawyers in the Indian Freedom Movement – The Bar Council of India". Barcouncilofindia.org. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ Moreman, Tim (2013). The Jungle, Japanese and the British Commonwealth Armies at War, 1941–45: Fighting Methods, Doctrine and Training for Jungle Warfare. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-76456-2.

- ^ Marston, Daniel (2014). The Indian Army and the End of the Raj. Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society, 23. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89975-8.

- Bipan Chandra, Amales Tripathi, Barun De. Freedom Struggle. India: National Book Struggle. ISBN 81-237-0249-X.

قراءات إضافية

- The Indian National Congress: An Historical Sketch, by Frederick Marion De Mello. Published by H. Milford, Oxford university press, 1934.

- The Indian National Congress, by Hemendra Nath Das Gupta. Published by J. K. Das Gupta, 1946.

- Indian National Congress: A Descriptive Bibliography of India's Struggle for Freedom, by Jagdish Saran Sharma. Published by S. Chand, 1959.

- Social Factors in the Birth and Growth of the Indian National Congress Movement, by Ramparkash Dua. Published by S. Chand, 1967.

- Split in a Predominant Party: The Indian National Congress in 1969, by Mahendra Prasad Singh. Abhinav Publications, 1981. ISBN 8170171407.

- Concise History of the Indian National Congress, 1885-1947, by B. N. Pande, Nisith Ranjan Ray, Ravinder Kumar, Manmath Nath Das. Published by Vikas Pub. House, 1985. ISBN 0706930207.

- The Indian National Congress: An Analytical Biography, by Om P. Gautam. Published by B.R. Pub. Corp., 1985.

- A Century of Indian National Congress, 1885-1985, by Pran Nath Chopra, Ram Gopal, Moti Lal Bhargava. Published by Agam Prakashan, 1986.

- The Congress Ideology and Programme, 1920-1985, by Pitambar Datt Kaushik . Published by Gitanjali Pub. House, 1986. ISBN 8185060169.

- Struggling and Ruling: The Indian National Congress, 1885-1985, by Jim Masselos. Published by Sterling Publishers, 1987.

- The Encyclopaedia of Indian National Congress, by A. Moin Zaidi, Shaheda Gufran Zaidi, Indian Institute of Applied Political Research. Published by S.Chand, 1987.

- Indian National Congress: A Reconstruction, by Iqbal Singh, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. Published by Riverdale Company, 1988. ISBN 0913215325.

- INC, the Glorious Tradition, by A. Moin Zaidi, Indian National Congress. AICC. Published by Indian Institute of Applied Political Research, 1989.

- Indian National Congress: A Select Bibliography, by Manikrao Hodlya Gavit, Attar Chand. Published by U.D.H. Pub. House, 1989. ISBN 8185044058.

- The Story of Congress Pilgrimage: 1885-1985, by A. Moin Zaidi, Indian National Congress. Published by Indian Institute of Applied Political Research, 1990. ISBN 8185355460. (7 vols)

- Indian National Congress in England, by Harish P. Kaushik. Published by Friends Publications, 1991.

- Women in Indian National Congress, 1921-1931, by Rajan Mahan. Published by Rawat Publications, 1999.

- History of Indian National Congress, 1885-2002, by Deep Chand Bandhu. Published by Kalpaz Publications, 2003. ISBN 8178350904.

وصلات خارجية

- Official Indian National Congress website

- Indian National Congress Discussion Group

- Congress Archives

- Congress Media

- Congress Sandesh

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using infobox Indian political party with unknown parameters

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing هندي-language text

- أحزاب سياسية هندية

- أحزاب سياسية تأسست في 1885

- حزب الؤمتر الهندي

- أحزاب اشتراكية

- حركة الإستقلال الهندية

- Subhas Chandra Bose