الهند البريطانية

الهند | |

|---|---|

| 1858–1947 | |

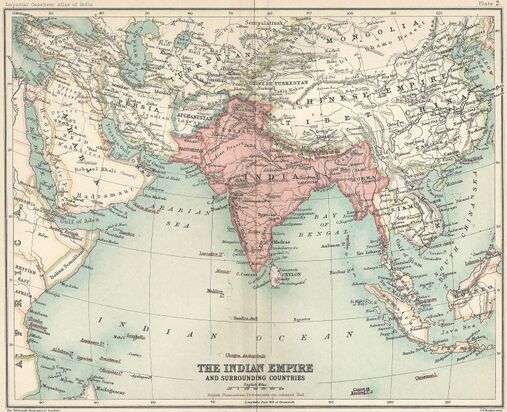

Political subdivisions of the British Raj in 1909. British India is shown in two shades of pink; Sikkim, نيپال، بوتان, and the princely states are shown in yellow. | |

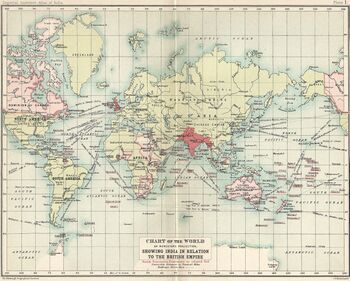

The British Raj in relation to the British Empire in 1909 | |

| المكانة | البنية السياسية الإمبراطورية (comprising British India[أ] والولايات الأميرية[ب][1] |

| العاصمة | |

| اللغات الرسمية | |

| صفة المواطن | Indians, British Indians |

| ملكة/ملكة-إمبراطورة/ملك-إمبراطور | |

• 1858–1876 (Queen); 1876–1901 (Queen-Empress) | Victoria |

• 1901–1910 | إدوارد السابع |

• 1910–1936 | جورج الخامس |

• 1936 | إدوارد الثامن |

• 1936–1947 (الأخير) | جورج السادس |

| نائب الملك | |

• 1858–1862 (first) | Charles Canning |

• 1947 (الأخير) | Louis Mountbatten |

| Secretary of State | |

• 1858–1859 (first) | Edward Stanley |

• 1947 (last) | William Hare |

| التشريع | Imperial Legislative Council |

| Council of State | |

| Central Legislative Assembly | |

| التاريخ | |

| 10 May 1857 | |

| 2 August 1858 | |

| 18 July 1947 | |

| took effect Midnight, 14–15 August 1947 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 4،993،650 km2 (1،928،060 sq mi) |

| Currency | الروبية الهندية |

الهند البريطانية أو الراج البريطاني هي المرحلة التاريخية التي استعمرت فيها مناطق الهند وباكستان وبنغلاديش وميانمار من قِبل الإمبراطورية البريطانية منذ بداية القرن 19 حتى منتصف القرن 20. في اللغة الهندية، كلمة "راج" تعني "الحكم"، أي فترة الحكم البريطاني في المنطقة. كانت المناطق المستعمرة تمثل دولة واحدة. الحكم البريطاني في الهند انتهى في 15 أغسطس 1947.

بدأ الاستعمار البريطاني في شبه الجزيرة الهندية في عام 1858. معظم الأراضي التي وقعت في منطقة الهند البريطانية لم تحكم بواسطة الإمبراطورية البريطانية بشكل مباشر بل كانت ولايات أميرية مستقلة اسمياً، حكمت بواسطة الماهاراجات والراجا والثاكور والنواب الذين وقعوا معاهدات مع بريطانيا بشأن سيادتهم، وعرف هذا النظام بالحلف الإضافي. كانت مستعمرة عدن جزء من الهند البريطانية أيضاً منذ عام 1839، هذا بالإضافة إلى ميانمار (عرفت سابقاً باسم بورما) منذ عام 1886. استقلت كلتا المستعمرتين من الإمبراطورية البريطانية في عام 1937. حكمت أرض الصومال البريطانية بين عامي 1884 - 1898، وسنغافورة بين عامي 1819 - 1867 كجزء من الهند. بالرغم من أن سريلانكا تقع في شبه الجزيرة الهندية، إلا أنها حكمت مباشرة من لندن بخلاف الهند البريطانية.

الامتداد الجغرافي

The British Raj extended over almost all present-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Myanmar, except for small holdings by other European nations such as Goa and Pondicherry.[10] This area is very diverse, containing the Himalayan mountains, fertile floodplains, the Indo-Gangetic Plain, a long coastline, tropical dry forests, arid uplands, and the Thar Desert.[11] In addition, at various times, it included Aden (from 1858 to 1937),[12] Lower Burma (from 1858 to 1937), Upper Burma (from 1886 to 1937), British Somaliland (briefly from 1884 to 1898), and the Straits Settlements (briefly from 1858 to 1867). Burma was separated from India and directly administered by the British Crown from 1937 until its independence in 1948. The Trucial States of the Persian Gulf and the other states under the Persian Gulf Residency were theoretically princely states as well as presidencies and provinces of British India until 1947 and used the rupee as their unit of currency.[13]

Among other countries in the region, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), which was referred to coastal regions and northern part of the island at that time, was ceded to Britain in 1802 under the Treaty of Amiens. These coastal regions were temporarily administered under Madras Presidency between 1793 and 1798,[14] but, for later periods, the British governors reported to London, and it was not part of the Raj. The kingdoms of Nepal and Bhutan, having fought wars with the British, subsequently signed treaties with them and were recognised by the British as independent states.[15][16] The Kingdom of Sikkim was established as a princely state after the Anglo-Sikkimese Treaty of 1861; however, the issue of sovereignty was left undefined.[17] The Maldive Islands were a British protectorate from 1887 to 1965 but not part of British India.[18]

التاريخ

1858–1868: أعقاب التمرد وانتقادات وردود أفعال

Lakshmibai, Rani of Jhansi, one of the principal leaders of the Great Uprising of 1857, who had lost her kingdom by the Doctrine of lapse

The proclamation to the "Princes, Chiefs, and People of India", issued by Queen Victoria on 1 November 1858

Sir Syed Ahmed Khan founder of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College, wrote one of the early critiques, The Causes of the Indian Mutiny.

An 1887 souvenir portrait of Queen Victoria as Empress of India, 30 years after the Great Uprising

خط زمني للأحداث والتشريعات والأشغال الرئيسية

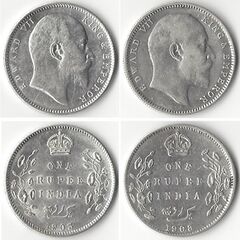

- The reigning British monarchs during the period of the British Raj, 1858–1947, on silver one-rupee coins.

Silver one rupee coins showing Edward VII, King-Emperor, 1903 (left) and 1908 (right)

Silver one rupee coins used in India during the British Raj, showing George V, King-Emperor, 1913 (left) and 1919 (right)

| الفترة | نائب الملك | الأحداث والتشريعات والأشغال الرئيسية |

|---|---|---|

| 1 نوفمبر 1858 – 21 March 1862 |

Viscount Canning[19] | 1858 reorganisation of British Indian Army (contemporaneously and hereafter Indian Army) Construction begins (1860): University of Bombay, University of Madras, and University of Calcutta Indian Penal Code passed into law in 1860. Upper Doab famine of 1860–1861 Indian Councils Act 1861 Establishment of Archaeological Survey of India in 1861 James Wilson, financial member of Council of India, reorganises customs, imposes income tax, creates paper currency. Indian Police Act 1861: creation of the Imperial Police, later known as the Indian Police Service. |

| 21 مارس 1862 – 20 November 1863 |

Earl of Elgin | Viceroy dies prematurely in Dharamsala in 1863 |

| 12 January 1864 – 12 January 1869 |

Sir John Lawrence, Bt[20] | Anglo-Bhutan Duar War (1864–1865) Orissa famine of 1866 Rajputana famine of 1869 Creation of Department of Irrigation. Creation of the Imperial Forestry Service in 1867 (now the Indian Forest Service). "Nicobar Islands annexed and incorporated into India 1869" |

| 12 January 1869 – 8 February 1872 |

Earl of Mayo[21] | Creation of Department of Agriculture (now Ministry of Agriculture) Major extension of railways, roads, and canals Indian Councils Act 1870 Creation of Andaman and Nicobar Islands as a Chief Commissionership (1872). Assassination of Lord Mayo in the Andamans. |

| 3 May 1872 – 12 April 1876 |

Lord Northbrook[21] | Deaths in Bihar famine of 1873–1874 prevented by import of rice from Burma. Gaikwad of Baroda dethroned for misgovernment; dominions passed to a child prince. Indian Councils Act 1874 Visit of the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII, in 1875–76. |

| 12 April 1876 – 8 June 1880 |

Lord Lytton | Baluchistan established as a Chief Commissionership Queen Victoria (in absentia) proclaimed Empress of India at Delhi Durbar of 1877. Great Famine of 1876–1878: 5.25 million dead; reduced relief offered at expense of Rs. 80 million. Creation of Famine Commission of 1878–80 under Sir Richard Strachey. Indian Forest Act of 1878 Second Anglo-Afghan War. |

| 8 June 1880 – 13 December 1884 |

Marquess of Ripon[22] | End of Second Anglo-Afghan War. Repeal of Vernacular Press Act of 1878. Compromise on the Ilbert Bill. Local Government Acts extend self-government from towns to country. University of Punjab established in Lahore in 1882 Famine Code promulgated in 1883 by the Government of India. Creation of the Education Commission. Creation of indigenous schools, especially for Muslims. Repeal of import duties on cotton and of most tariffs. Railway extension. |

| 13 December 1884 – 10 December 1888 |

Earl of Dufferin[23][24] | Passage of Bengal Tenancy Bill Third Anglo-Burmese War. Joint Anglo-Russian Boundary Commission appointed for the Afghan frontier. Russian attack on Afghans at Panjdeh (1885). The Great Game in full play. Report of Public Services Commission of 1886–87, creation of the Imperial Civil Service (later the Indian Civil Service (ICS), and today the Indian Administrative Service) University of Allahabad established in 1887 Queen Victoria's Jubilee, 1887. |

| 10 December 1888 – 11 October 1894 |

Marquess of Lansdowne[25] | Strengthening of NW Frontier defence. Creation of Imperial Service Troops consisting of regiments contributed by the princely states. Gilgit Agency leased in 1899 British Parliament passes Indian Councils Act 1892, opening the Imperial Legislative Council to Indians. Revolution in princely state of Manipur and subsequent reinstatement of ruler. High point of The Great Game. Establishment of the Durand Line between British India and Afghanistan, Railways, roads, and irrigation works begun in Burma. Border between Burma and Siam finalised in 1893. Fall of the rupee, resulting from the steady depreciation of silver currency worldwide (1873–93). Indian Prisons Act of 1894 |

| 11 October 1894 – 6 January 1899 |

Earl of Elgin | Reorganisation of Indian Army (from Presidency System to the four Commands). Pamir agreement Russia, 1895 The Chitral Campaign (1895), the Tirah campaign (1896–97) Indian famine of 1896–1897 beginning in Bundelkhand. Bubonic plague in Bombay (1896), Bubonic plague in Calcutta (1898); riots in wake of plague prevention measures. Establishment of Provincial Legislative Councils in Burma and Punjab; the former a new Lieutenant Governorship. |

| 6 January 1899 – 18 November 1905 |

Lord Curzon of Kedleston[26][27] | Creation of the North-West Frontier Province under a Chief Commissioner (1901). Indian famine of 1899–1900. Return of the bubonic plague, 1 million deaths Financial Reform Act of 1899; Gold Reserve Fund created for India. Punjab Land Alienation Act Inauguration of Department (now Ministry) of Commerce and Industry. Death of Queen Victoria (1901); dedication of the Victoria Memorial Hall, Calcutta as a national gallery of Indian antiquities, art, and history. Coronation Durbar in Delhi (1903); Edward VII (in absentia) proclaimed Emperor of India. Francis Younghusband's British expedition to Tibet (1903–04) North-Western Provinces (previously Ceded and Conquered Provinces) and Oudh renamed United Provinces in 1904 Reorganisation of Indian Universities Act (1904). Systemisation of preservation and restoration of ancient monuments by Archaeological Survey of India with the Indian Ancient Monument Preservation Act. Inauguration of agricultural banking with Cooperative Credit Societies Act of 1904 Partition of Bengal; new province of East Bengal and Assam under a Lieutenant-Governor. Census of 1901 gives the total population at 294 million, including 62 million in the princely states and 232 million in British India.[28] About 170,000 are Europeans. 15 million men and 1 million women are literate. Of those school-aged, 25% of the boys and 3% of the girls attend. There are 207 million Hindus, and 63 million Muslims, along with 9 million Buddhists (in Burma), 3 million Christians, 2 million Sikhs, 1 million Jains, and 8.4 million who practise animism.[29] |

| 18 November 1905 – 23 November 1910 |

Earl of Minto[30] | Creation of the Railway Board Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 Indian Councils Act 1909 (also Minto–Morley Reforms) Appointment of Indian Factories Commission in 1909. Establishment of Department of Education in 1910 (now Ministry of Education) |

| 23 November 1910 – 4 April 1916 |

Lord Hardinge of Penshurst | Visit of King George V and Queen Mary in 1911: commemoration as Emperor and Empress of India at last Delhi Durbar King George V announces creation of new city of New Delhi to replace Calcutta as capital of India. Indian High Courts Act 1911 Indian Factories Act of 1911 Construction of New Delhi, 1912–1929 World War I, Indian Army in: Western Front, Belgium, 1914; German East Africa (Battle of Tanga, 1914); Mesopotamian campaign (Battle of Ctesiphon, 1915; Siege of Kut, 1915–16); Battle of Galliopoli, 1915–16 Passage of Defence of India Act 1915 |

| 4 April 1916 – 2 April 1921 |

Lord Chelmsford | Indian Army in: Mesopotamian campaign (Fall of Baghdad, 1917); Sinai and Palestine campaign (Battle of Megiddo, 1918) Passage of Rowlatt Act, 1919 Government of India Act 1919 (also Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms) Jallianwala Bagh massacre, 1919 Third Anglo-Afghan War, 1919 University of Rangoon established in 1920. Indian Passport Act of 1920: British Indian passport introduced |

| 2 April 1921 – 3 April 1926 |

Earl of Reading | University of Delhi established in 1922. Indian Workers Compensation Act of 1923 |

| 3 April 1926 – 18 April 1931 |

Lord Irwin | Indian Trade Unions Act of 1926, Indian Forest Act, 1927 Appointment of Royal Commission of Indian Labour, 1929 Indian Constitutional Round Table Conferences, London, 1930–32, Gandhi–Irwin Pact, 1931. |

| 18 April 1931 – 18 April 1936 |

Earl of Willingdon | New Delhi inaugurated as capital of India, 1931. Indian Workmen's Compensation Act of 1933 Indian Factories Act of 1934 Royal Indian Air Force created in 1932. Indian Military Academy established in 1932. Government of India Act 1935 Creation of Reserve Bank of India |

| 18 April 1936 – 1 October 1943 |

Marquess of Linlithgow | Indian Payment of Wages Act of 1936 Burma administered independently after 1937 with creation of new cabinet position Secretary of State for India and Burma, and with the Burma Office separated off from the India Office Indian Provincial Elections of 1937 Cripps' mission to India, 1942. Indian Army in Mediterranean, Middle East and African theatres of World War II (North African campaign): (Operation Compass, Operation Crusader, First Battle of El Alamein, Second Battle of El Alamein. East African campaign, 1940, Anglo-Iraqi War, 1941, Syria–Lebanon campaign, 1941, Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran, 1941) Indian Army in Battle of Hong Kong, Battle of Malaya, Battle of Singapore Burma campaign of World War II begins in 1942. |

| 1 October 1943 – 21 February 1947 |

Viscount Wavell | Indian Army becomes, at 2.5 million men, the largest all-volunteer force in history. World War II: Burma Campaign, 1943–45 (Battle of Kohima, Battle of Imphal) Bengal famine of 1943 Indian Army in Italian campaign (Battle of Monte Cassino) British Labour Party wins UK General Election of 1945 with Clement Attlee becoming prime minister. 1946 Cabinet Mission to India Indian Elections of 1946. |

| 21 February 1947 – 15 August 1947 |

Viscount Mountbatten of Burma | Indian Independence Act 1947 of the British Parliament enacted on 18 July 1947. Radcliffe Award, August 1947 Partition of India, August 1947 India Office and position of Secretary of State for India abolished; ministerial responsibility within the United Kingdom for British relations with India and Pakistan transferred to the Commonwealth Relations Office. |

التعليم

Universities in Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras were established in 1857, just before the Rebellion. By 1890 some 60,000 Indians had matriculated, chiefly in the liberal arts or law. About a third entered public administration, and another third became lawyers. The result was a very well educated professional state bureaucracy. By 1887 of 21,000 mid-level civil services appointments, 45% were held by Hindus, 7% by Muslims, 19% by Eurasians (European father and Indian mother), and 29% by Europeans. Of the 1000 top-level civil services positions, almost all were held by Britons, typically with an Oxbridge degree.[31] The government, often working with local philanthropists, opened 186 universities and colleges of higher education by 1911; they enrolled 36,000 students (over 90% men). By 1939 the number of institutions had doubled and enrolment reached 145,000. The curriculum followed classical British standards of the sort set by Oxford and Cambridge and stressed English literature and European history. Nevertheless, by the 1920s the student bodies had become hotbeds of Indian nationalism.[32]

انظر أيضاً

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| مستعمرة الهند | |||||

| الهند الپرتغالية | 1505–1961 | ||||

| كازا دا إنديا | 1434–1833 | ||||

| شركة الهند الشرقية البرتغالية | 1628–1633 | ||||

| الهند الهولندية | 1605–1825 | ||||

| الهند الدنماركية | 1696–1869 | ||||

| الهند الفرنسية | 1759–1954 | ||||

| الإمبراطورية البريطانية في الهند | |||||

| شركة الهند الشرقية | 1612–1757 | ||||

| حكم الشركة في الهند | 1757–1857 | ||||

| الراج البريطاني | 1858–1947 | ||||

| الحكم البريطاني في بورما | 1826–1948 | ||||

| الهند البريطانية | 1612–1947 | ||||

| الولايات الأميرية | 1765–1947 | ||||

| تقسيم الهند | 1947 | ||||

تاريخ جنوب آسيا | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| العصر الحجري | 70,000–3300 ق.م. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • ثقافة مهرگره | • 7000–3300 ق.م. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| حضارة وادي السند | 3300–1700 ق.م. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ثقافة هرپـّان المتأخرة | 1700–1300 ق.م. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الفترة الڤيدية | 1500–500 ق.م. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| العصر الحديدي | 1200–300 ق.م. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • مهاجناپادا | • 700–300 ق.م. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • امبراطورية ماگادا | • 545 ق.م. - 550 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • امبراطورية موريا | • 321–184 ق.م. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الممالك الوسيطة | 250 ق.م.–1279 م | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • امبراطورية چولا | • 250 ق.م.–1070 م | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • ساتاڤاهانا | • 230 ق.م.–220 م | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • امبراطورية كوشان | • 60–240 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • امبراطورية گوپتا | • 280–550 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • امبراطورية پالا | • 750–1174 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • أسرة چالوكيا | • 543–753 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • راشتراكوتا | • 753–982 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • امبراطورية چالوكيا الغربية | • 973–1189 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • مملكة هويسالا | 1040–1346 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • امبراطورية كاكاتيا | 1083–1323 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| السلطنات الإسلامية | 1206–1596 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • سلطنة دلهي | • 1206–1526 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • سلطنات الدكن | • 1490–1596 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| مملكة أهوم | 1228–1826 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| امبراطورية ڤيجايانگرا | 1336–1646 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| سلطنة المغول | 1526–1858 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| امبراطورية ماراثا | 1674–1818 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| سلطنة دراني | 1747–1823 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| اتحاد السيخ | 1716–1799 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| امبراطورية السيخ | 1801–1849 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| شركة الهند الشرقية البريطانية | 1757–1858 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الراج البريطاني | 1858–1947 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الدول المعاصرة | 1947–الحاضر | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| تواريخ الأمم بنگلادش • بوتان • جمهورية الهند المالديڤ • نيپال • پاكستان • سري لانكا | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| تواريخ إقليمية | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| تآريخ متخصصة | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Colonial India

- Direct colonial rule

- Glossary of the British Raj (Hindi-Urdu words)

- Historiography of the British Empire

- Legislatures of British India

- List of governors-general of India

- Subsidiary alliance, the status of princely states

- Star of India flag used during the British Raj

- British North America

- Flags of British India

ملاحظات

- ^ a quasi-federation of presidencies and provinces directly governed by the British Crown through the Viceroy and Governor-General of India

- ^ governed by Indian rulers, under the suzerainty of The British Crown exercised through the Viceroy of India)

- ^ Simla was the summer capital of the Government of British India, not of the British Raj, i.e. the British Indian Empire, which included the Princely States.[3]

- ^ The proclamation for New Delhi to be the capital was made in 1911, but the city was inaugurated as the capital of the Raj in February 1931.

- ^ English was the language of the courts and government.

- ^ Urdu was also given official status in large parts of northern India, as were vernaculars elsewhere.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

- ^ Outside northern India, the local vernaculars were used as official language in the lower courts and in government offices.[8]

- ^ The only other emperor during this period, Edward VIII (reigned January to December 1936), did not issue any Indian currency under his name.

المراجع

- ^ Interpretation Act 1889 (52 & 53 Vict. c. 63), s. 18.

- ^ "Calcutta (Kalikata)", The Imperial Gazetteer of India, IX, Published under the Authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1908, p. 260, http://dsal.uchicago.edu/reference/gazetteer/pager.html?volume=9&objectid=DS405.1.I34_V09_266.gif, retrieved on 24 May 2022, "—Capital of the Indian Empire, situated in 22° 34' N and 88° 22' E, on the east or left bank of the Hooghly river, within the Twenty-four Parganas District, Bengal"

- ^ "Simla Town", The Imperial Gazetteer of India, XXII, Published under the Authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1908, p. 260, http://dsal.uchicago.edu/reference/gazetteer/pager.html?objectid=DS405.1.I34_V09_266.gif, retrieved on 24 May 2022, "—Head-quarters of Simla District, Punjab, and the summer capital of the Government of India, situated on a transverse spur of the Central Himālayan system system, in 31° 6' N and 77° 10' E, at a mean elevation above sea-level of 7,084 feet."

- ^ Lelyveld, David (1993). "Colonial Knowledge and the Fate of Hindustani". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 35 (4): 665–682. doi:10.1017/S0010417500018661. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 179178. S2CID 144180838. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

The earlier grammars and dictionaries made it possible for the British government to replace Persian with vernacular languages at the lower levels of the judicial and revenue administration in 1837, that is, to standardize and index terminology for official use and provide for its translation to the language of the ultimate ruling authority, English. For such purposes, Hindustani was equated with Urdu, as opposed to any geographically defined dialect of Hindi and was given official status through large parts of north India. Written in the Persian script with a largely Persian and, via Persian, an Arabic vocabulary, Urdu stood at the shortest distance from the previous situation and was easily attainable by the same personnel. In the wake of this official transformation, the British government began to make its first significant efforts on behalf of vernacular education.

- ^ Dalby, Andrew (2004) [1998]. "Hindi". A Dictionary of Languages: The definitive reference to more than 400 languages. A & C Black Publishers. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-7136-7841-3.

In the government of northern India Persian ruled. Under the British Raj, Persian eventually declined, but, the administration remaining largely Muslim, the role of Persian was taken not by Hindi but by Urdu, known to the British as Hindustani. It was only as the Hindu majority in India began to assert itself that Hindi came into its own.

- ^ Vejdani, Farzin (2015), Making History in Iran: Education, Nationalism, and Print Culture, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 24–25, ISBN 978-0-8047-9153-3, "Although the official languages of administration in India shifted from Persian to English and Urdu in 1837, Persian continued to be taught and read there through the early twentieth century."

- ^ Everaert, Christine (2010), Tracing the Boundaries between Hindi and Urdu, Leiden and Boston: BRILL, pp. 253–254, ISBN 978-90-04-17731-4, "It was only in 1837 that Persian lost its position as official language of India to Urdu and to English in the higher levels of administration."

- ^ أ ب Dhir, Krishna S. (2022). The Wonder That Is Urdu. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 138. ISBN 978-81-208-4301-1.

The British used the Urdu language to effect a shift from the prior emphasis on the Persian language. In 1837, the British East India Company adopted Urdu in place of Persian as the co-official language in India, along with English. In the law courts in Bengal and the North-West Provinces and Oudh (modern day Uttar Pradesh) a highly technical form of Urdu was used in the Nastaliq script, by both Muslims and Hindus. The same was the case in the government offices. In the various other regions of India, local vernaculars were used as official language in the lower courts and in government offices. ... In certain parts South Asia, Urdu was written in several scripts. Kaithi was a popular script used for both Urdu and Hindi. By 1880, Kaithi was used as court language in Bihar. However, in 1881, Hindi in Devanagari script replaced Urdu in the Nastaliq script in Bihar. In Panjab, Urdu was written in Nastaliq, Devanagari, Kaithi, and Gurumukhi.

In April 1900, the colonial government of the North-West Provinces and Oudh granted equal official status to both, Devanagari and Nastaliq scripts. However, Nastaliq remained the dominant script. During the 1920s, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi deplored the controversy and the evolving divergence between Urdu and Hindi, exhorting the remerging of the two languages as Hindustani. However, Urdu continued to draw from Persian, Arabic, and Chagtai, while Hindi did the same from Sanskrit. Eventually, the controversy resulted in the loss of the official status of the Urdu language. - ^ Bayly, C. A. (1988). Indian Society and the making of the British Empire. New Cambridge History of India series. Cambridge University Press. p. 122. ISBN 0-521-25092-7.

The use of Persian was abolished in official correspondence (1835); the government's weight was thrown behind English-medium education and Thomas Babington Macaulay's Codes of Criminal and Civil Procedure (drafted 1841–2, but not completed until the 1860s) sought to impose a rational, Western legal system on the amalgam of Muslim, Hindu and English law which had been haphazardly administered in British courts. The fruits of the Bentinck era were significant. But they were only of general importance in so far as they went with the grain of social changes which were already gathering pace in India. The Bombay and Calcutta intelligentsia were taking to English education well before the Education Minute of 1836. Flowery Persian was already giving way in north India to the fluid and demotic Urdu. As for changes in the legal system, they were only implemented after the Rebellion of 1857 when communications improved and more substantial sums of money were made available for education.

- ^ Smith, George (1882). The Geography of British India, Political & Physical. London: John Murray. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0.

- ^ Marshall (2001), p. 384

- ^ Subodh Kapoor (January 2002). The Indian encyclopaedia: biographical, historical, religious ..., Volume 6. Cosmo Publications. p. 1599. ISBN 978-81-7755-257-7.

- ^ Codrington, 1926, Chapter X:Transition to British administration

- ^ "Nepal: Cultural life". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2008. Archived from the original on 24 November 2015.

- ^ "Bhutan". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2008. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ "Sikkim | History, Map, Capital, & Population". Britannica (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ "Maldives | History, Points of Interest, Location, & Tourism". Britannica (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 2 December 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ Michael Maclagan (1963). "Clemency" Canning: Charles John, 1st Earl Canning, Governor-General and Viceroy of India, 1856–1862. Macmillan. p. 212. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ William Ford (1887). John Laird Mair Lawrence, a viceroy of India, by William St. Clair. pp. 186–253.

- ^ أ ب Sir William Wilson Hunter (1876). A life of the Earl of Mayo, fourth viceroy of India. Smith, Elder, & Company. pp. 181–310.

- ^ Sarvepalli Gopal (1953). The viceroyalty of Lord Ripon, 1880–1884. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ Briton Martin, Jr. "The Viceroyalty of Lord Dufferin", History Today, (Dec 1960) 10#12 pp. 821–30, and (Jan 1961) 11#1 pp. 56–64

- ^ Sir Alfred Comyn Lyall (1905). The life of the Marquis of Dufferin and Ava. Vol. 2. pp. 72–207.

- ^ Sir George Forrest (1894). The administration of the Marquis of Lansdowne as Viceroy and Governor-general of India, 1888–1894. Office of the Supdt. of Government Print. p. 40.

- ^ Michael Edwardes, High Noon of Empire: India under Curzon (1965)

- ^ H. Caldwell Lipsett (1903). Lord Curzon in India: 1898–1903. R.A. Everett.

- ^ The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Vol. I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1909. p. 449. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ Ernest Hullo, "India", in Catholic Encyclopedia (1910) vol. 7 online Archived 23 فبراير 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Manmath Nath Das (1964). India under Morley and Minto: politics behind revolution, repression and reforms. G. Allen and Unwin. OCLC 411335. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ Moore 2001a, p. 431

- ^ Zareer Masani (1988). Indian Tales of the Raj p. 89

ببليوجرافيا

مسوح

- Allan, J., T. Wolseley Haig, H. H. Dodwell. The Cambridge Shorter History of India (1934), 996 pp.

- Bandhu, Deep Chand. History of Indian National Congress (2003), 405 pp.

- Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar (2004), From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India, Orient Longman. pp. xx, 548., ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2.

- Bayly, C. A. (1990), Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire (The New Cambridge History of India), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 248, ISBN 978-0-521-38650-0.

- Brendon, Piers (28 October 2008). The Decline and Fall of the British Empire, 1781-1997 (in الإنجليزية). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-27028-3.

- Brown, Judith M. (1994), Modern India: The Origins of an Asian Democracy, Oxford University Press. pp. xiii, 474, ISBN 978-0-19-873113-9.

- Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (2004), Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy (2nd ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-30787-1, https://archive.org/details/modernsouthasiah00bose

- Chhabra, G. S. (2005), Advanced Study in the History of Modern India, III (Revised ed.), New Delhi: Lotus Press, p. 2, ISBN 978-81-89093-08-2, https://books.google.com/books?id=e08-yhBFfpAC, retrieved on 15 September 2018

- Copland, Ian (2001), India 1885–1947: The Unmaking of an Empire (Seminar Studies in History Series), Harlow and London: Pearson Longmans. pp. 160, ISBN 978-0-582-38173-5

- Coupland, Reginald. India: A Re-Statement (Oxford University Press, 1945)

- Dodwell H. H., ed. The Cambridge History of India. Volume 6: The Indian Empire 1858–1918. With Chapters on the Development of Administration 1818–1858 (1932) 660 pp. online edition; also published as vol 5 of the Cambridge History of the British Empire

- Gilmour, David. The British in India: A Social History of the Raj (2018); expanded edition of The Ruling Caste: Imperial Lives in the Victorian Raj (2007) Excerpt and text search

- Herbertson, A.J. and O.J.R. Howarth. eds. The Oxford Survey of the British Empire (6 vol 1914) online vol 2 on Asia pp. 1–328 on India

- James, Lawrence. Raj: The Making and Unmaking of British India (2000)

- Judd, Denis (2004), The Lion and the Tiger: The Rise and Fall of the British Raj, 1600–1947, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. xiii, 280, ISBN 978-0-19-280358-0.

- Louis, William Roger, and Judith M. Brown, eds. The Oxford History of the British Empire (5 vol 1999–2001), with numerous articles on the Raj

- Low, D. A. (1993), Eclipse of Empire, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-45754-5, https://books.google.com/books?id=QBaYddlnKBEC

- Ludden, David E. (2002), India And South Asia: A Short History, Oxford: Oneworld, ISBN 978-1-85168-237-9

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra; Raychaudhuri, Hemchandra; Datta, Kalikinkar (1950), An advanced history of India

- Majumdar, R. C. ed. (1970). British paramountcy and Indian renaissance. (The History and Culture of the Indian People) Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Mansingh, Surjit The A to Z of India (2010), a concise historical encyclopaedia

- Marshall, P. J. (2001), The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire, 400 pp., Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press., ISBN 978-0-521-00254-7.

- Markovits, Claude (2004), A History of Modern India, 1480–1950, Anthem Press, ISBN 978-1-84331-004-4, https://books.google.com/books?id=uzOmy2y0Zh4C, retrieved on 18 June 2015

- Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006), A Concise History of Modern India (Cambridge Concise Histories), Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. xxxiii, 372, ISBN 978-0-521-68225-1

- Moon, Penderel. The British Conquest and Dominion of India (2 vol. 1989) 1235 pp. the fullest scholarly history of political and military events from a British top-down perspective;

- Oldenburg, Philip (2007), "India: Movement for Freedom", Encarta Encyclopedia

- Panikkar, K. M. (1953). Asia and Western dominance, 1498–1945, by K.M. Panikkar. London: G. Allen and Unwin.

- Peers, Douglas M. (2006), India under Colonial Rule 1700–1885, Harlow and London: Pearson Longmans. pp. xvi, 163, ISBN 978-0-582-31738-3.

- Riddick, John F. The history of British India: a chronology (2006) excerpt and text search, covers 1599–1947

- Riddick, John F. Who Was Who in British India (1998), covers 1599–1947

- Robb, Peter (2002), A History of India, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-230-34549-2, https://books.google.com/books?id=GQ-2VH1LO_EC

- Sarkar, Sumit (2004), Modern India, 1885–1947, Delhi: Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-333-90425-1, https://archive.org/details/modernindia1885100sark

- Smith, Vincent A. (1958) The Oxford History of India (3rd ed.) the Raj section was written by Percival Spear

- Somervell, D.C. The Reign of King George V, (1936) covers Raj 1910–35 pp. 80–84, 282–291, 455–464 online free

- Spear, Percival (1990), A History of India, Volume 2, New Delhi and London: Penguin Books. pp. 298, ISBN 978-0-14-013836-8, https://books.google.com/books?id=K2H_v0t5jTkC&pg=PA147.

- Stein, Burton (2001), A History of India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-565446-2.

- Stein, Burton (2010), A History of India (2nd ed.), John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-1-4443-2351-1, https://books.google.com/books?id=QY4zdTDwMAQC, retrieved on 13 February 2016.

- Thompson, Edward, and G.T. Garratt. Rise and Fulfilment of British Rule in India (1934) 690 pages; scholarly survey, 1599–1933 excerpt and text search

- Wolpert, Stanley (2004), A New History of India (7th ed.), Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-516677-4.

- Wolpert, Stanley, ed. Encyclopedia of India (4 vol. 2005) comprehensive coverage by scholars

- Wolpert, Stanley A. (2006), Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-539394-1

مواضع متخصصة

- Baker, David (1993), Colonialism in an Indian Hinterland: The Central Provinces, 1820–1920, Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. xiii, 374, ISBN 978-0-19-563049-7

- Bayly, Christopher (2000), Empire and Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India, 1780–1870 (Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society), Cambridge University Press. pp. 426, ISBN 978-0-521-66360-1

- Bayly, Christopher; Harper, Timothy (2005), Forgotten Armies: The Fall of British Asia, 1941–1945, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01748-1, https://books.google.com/books?id=qXH9xGCWjYUC, retrieved on 22 September 2013

- Bayly, Christopher; Harper, Timothy (2007), Forgotten Wars: Freedom and Revolution in Southeast Asia, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-02153-2, https://books.google.com/books?id=0M4Pl_VCExgC, retrieved on 21 September 2013

- Bayly, Christopher Alan. Imperial Meridian: The British Empire and the World 1780–1830. (Routledge, 2016).

- Bose, Sudhindra (1916), Some Aspects of British Rule in India, Studies in the Social Sciences, V, Iowa City: The University, pp. 79–81, https://books.google.com/books?id=5wmGAAAAIAAJ, retrieved on 15 September 2018

- Bosma, Ulbe (2011), Emigration: Colonial circuits between Europe and Asia in the 19th and early 20th century, EGO – European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, retrieved: 25 March 2021 (pdf).

- Brown, Judith M. Gandhi: Prisoner of Hope (1991), scholarly biography

- Brown, Judith M.; Louis, Wm. Roger, eds. (2001), Oxford History of the British Empire: The Twentieth Century, Oxford University Press. pp. 800, ISBN 978-0-19-924679-3

- Buckland, C.E. Dictionary of Indian Biography (1906) 495 pp. full text

- Carrington, Michael (May 2013), "Officers, Gentlemen, and Murderers: Lord Curzon's campaign against "collisions" between Indians and Europeans, 1899–1905", Modern Asian Studies 47 (3): 780–819, doi:

- Chandavarkar, Rajnarayan (1998), Imperial Power and Popular Politics: Class, Resistance and the State in India, 1850–1950, (Cambridge Studies in Indian History & Society). Cambridge University Press. pp. 400, ISBN 978-0-521-59692-3.

- Chatterji, Joya (1993), Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932–1947, Cambridge University Press. pp. 323, ISBN 978-0-521-52328-8.

- Copland, Ian (2002), Princes of India in the Endgame of Empire, 1917–1947, (Cambridge Studies in Indian History & Society). Cambridge University Press. pp. 316, ISBN 978-0-521-89436-4.

- Das, Manmath Nath (1964). India under Morley and Minto: politics behind revolution, repression and reforms. G. Allen and Unwin. OCLC 411335.

- Davis, Mike (2001), Late Victorian Holocausts, Verso Books, ISBN 978-1-85984-739-8

- Dewey, Clive. Anglo-Indian Attitudes: The Mind of the Indian Civil Service (2003)

- Ewing, Ann. "Administering India: The Indian Civil Service", History Today, June 1982, 32#6 pp. 43–48, covers 1858–1947

- Fieldhouse, David (1996), "For Richer, for Poorer?", in Marshall, P. J., The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 400, pp. 108–146, ISBN 978-0-521-00254-7

- Gilmartin, David. 1988. Empire and Islam: Punjab and the Making of Pakistan. University of California Press. 258 pages. ISBN 978-0-520-06249-8.

- Gilmour, David. Curzon: Imperial Statesman (2006) excerpt and text search

- Gopal, Sarvepalli. British Policy in India 1858–1905 (2008)

- Gopal, Sarvepalli (1976), Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography, Harvard U. Press, ISBN 978-0-674-47310-2, https://books.google.com/books?id=Jj-4zmBLXq0C, retrieved on 21 February 2012

- Gopal, Sarvepalli. Viceroyalty of Lord Irwin 1926–1931 (1957)

- Gopal, Sarvepalli (1953), The Viceroyalty of Lord Ripon, 1880–1884, Oxford U. Press, https://books.google.com/books?id=eKE9AAAAIAAJ, retrieved on 21 February 2012

- Gould, William (2004), Hindu Nationalism and the Language of Politics in Late Colonial India, Cambridge U. Press. pp. 320, ISBN 978-1-139-45195-6, https://books.google.com/books?id=XNsganXnq-oC.

- Grove, Richard H. (2007), "The Great El Nino of 1789–93 and its Global Consequences: Reconstructing an Extreme Climate Even in World Environmental History", The Medieval History Journal 10 (1&2): 75–98, doi:

- Hall-Matthews, David (November 2008), "Inaccurate Conceptions: Disputed Measures of Nutritional Needs and Famine Deaths in Colonial India", Modern Asian Studies 42 (6): 1189–1212, doi:

- Headrick, Daniel R. (1988), The tentacles of progress: technology transfer in the age of imperialism, 1850–1940, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-505115-7

- Hyam, Ronald (2007), Britain's Declining Empire: The Road to Decolonisation, 1918–1968, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-86649-1

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III (1907), The Indian Empire, Economic (Chapter X: Famine), pp. 475–502, Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. pp. xxx, 1 map, 552.

- The Imperial Gazetteer of India, IV, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1909, https://archive.org/details/imperialgazettee04grea

- Jalal, Ayesha (1993), The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan, Cambridge U. Press, 334 pages.

- Kaminsky, Arnold P. The India Office, 1880–1910 (1986) excerpt and text search, focus on officials in London

- Khan, Yasmin (2007), The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan, Yale U. Press, 250 pages, ISBN 978-0-300-12078-3, https://archive.org/details/greatpartitionma00khan

- Khan, Yasmin. India At War: The Subcontinent and the Second World War (2015), wide-ranging scholarly survey excerpt; also published as Khan, Yasmin. The Raj at War: A People's History Of India's Second World War (2015) a major, comprehensive scholarly study

- Klein, Ira (July 2000), "Materialism, Mutiny and Modernization in British India", Modern Asian Studies 34 (3): 545–580, doi:

- Koomar, Roy Basanta (2009), The Labor Revolt in India, BiblioBazaar, LLC, pp. 13–14, ISBN 978-1-113-34966-8

- Kumar, Deepak. Science and the Raj: A Study of British India (2006)

- Lipsett, Chaldwell. Lord Curzon in India 1898–1903 (1903) excerpt and text search 128 pp

- Low, D. A. (2002), Britain and Indian Nationalism: The Imprint of Ambiguity 1929–1942, Cambridge University Press. pp. 374, ISBN 978-0-521-89261-2.

- MacMillan, Margaret. Women of the Raj: The Mothers, Wives, and Daughters of the British Empire in India (2007)

- Metcalf, Thomas R. (1991), The Aftermath of Revolt: India, 1857–1870, Riverdale Co. Pub. pp. 352, ISBN 978-81-85054-99-5

- Metcalf, Thomas R. (1997), Ideologies of the Raj, Cambridge University Press, pp. 256, ISBN 978-0-521-58937-6, https://books.google.com/books?id=TRcMoGSkRtIC&pg=PR8

- Moore, Robin J. (2001a), "Imperial India, 1858–1914", in Porter, Andrew N., Oxford History of the British Empire, III, Oxford University Press, pp. 422–446, ISBN 978-0-19-924678-6

- Moore, Robin J. "India in the 1940s", in Robin Winks, ed. Oxford History of the British Empire: Historiography, (2001b), pp. 231–242

- Nehru, Jawaharlal (1946), Discovery of India, Delhi: Oxford University Press, https://archive.org/details/DiscoveryOfIndia

- Porter, Andrew, ed. (2001), Oxford History of the British Empire: Nineteenth Century, Oxford University Press. pp. 800, ISBN 978-0-19-924678-6

- Raghavan, Srinath. India's War: World War II and the Making of Modern South Asia (2016). wide-ranging scholarly survey excerpt Archived 23 سبتمبر 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- Rai, Lajpat (2008), England's Debt to India: A Historical Narrative of Britain's Fiscal Policy in India, BiblioBazaar, LLC, pp. 263–281, ISBN 978-0-559-80001-6

- Raja, Masood Ashraf (2010), Constructing Pakistan: Foundational Texts and the Rise of Muslim National Identity, 1857–1947, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-547811-2

- Ramusack, Barbara (2004), The Indian Princes and their States (The New Cambridge History of India), Cambridge University Press. pp. 324, ISBN 978-0-521-03989-5

- Read, Anthony, and David Fisher; The Proudest Day: India's Long Road to Independence (W. W. Norton, 1999) Archive.org, borrowable

- Riddick, John F. The History of British India: A Chronology (2006) excerpt Archived 23 سبتمبر 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- Riddick, John F. Who Was Who in British India (1998); 5000 entries excerpt

- Satya, Laxman D. (2008). "British Imperial Railways in Nineteenth Century South Asia". Economic and Political Weekly. 43 (47): 69–77. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 40278213.

- Shaikh, Farzana (1989), Community and Consensus in Islam: Muslim Representation in Colonial India, 1860–1947, Cambridge University Press. pp. 272., ISBN 978-0-521-36328-0.

- Talbot, Ian; Singh, Gurharpal, eds. (1999), Region and Partition: Bengal, Punjab and the Partition of the Subcontinent, Oxford University Press. pp. 420, ISBN 978-0-19-579051-1.

- Thatcher, Mary. Respected Memsahibs: an Anthology (Hardinge Simpole, 2008)

- Tinker, Hugh (October 1968), "India in the First World War and after", Journal of Contemporary History 3 (4, 1918–19: From War to Peace): 89–107, doi:.

- Voigt, Johannes. India in The Second World War (1988)

- Wolpert, Stanley A. (2007), "India: British Imperial Power 1858–1947 (Indian nationalism and the British response, 1885–1920; Prelude to Independence, 1920–1947)", Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Wolpert, Stanley A. Jinnah of Pakistan (2005)

- Wolpert, Stanley A. Tilak and Gokhale: revolution and reform in the making of modern India (1962) full text online

التاريخ الاقتصادي والاجتماعي

- Anstey, Vera. The economic development of India (4th ed. 1952), 677 pp. thorough scholarly coverage; focus on 20th century down to 1939

- Ballhatchet, Kenneth. Race, Sex, and Class under the Raj: Imperial Attitudes and Policies and Their Critics, 1793–1905 (1980).

- Chaudhary, Latika, et al. eds. A New Economic History of Colonial India (2015)

- Derbyshire, I. D. (1987), "Economic Change and the Railways in North India, 1860–1914", Population Studies 21 (3): 521–545, doi:

- Chaudhuri, Nupur. "Imperialism and Gender." in Encyclopedia of European Social History, edited by Peter N. Stearns, (vol. 1, 2001), pp. 515–521. online emphasis on Raj.

- Dutt, Romesh C. The Economic History of India under early British Rule (1901); The Economic History of India in the Victorian Age (1906) online

- Gupta, Charu, ed. Gendering Colonial India: Reforms, Print, Caste and Communalism (2012)

- Hyam, Ronald. Empire and Sexuality: The British Experience (1990).

- Kumar, Dharma; Desai, Meghnad (1983), The Cambridge Economic History of India, 2, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-22802-2, https://books.google.com/books?id=9ew8AAAAIAAJ, retrieved on 15 September 2018

- Lockwood, David. The Indian Bourgeoisie: A Political History of the Indian Capitalist Class in the Early Twentieth Century (I.B. Tauris, 2012) 315 pages; focus on Indian entrepreneurs who benefited from the Raj, but ultimately sided with the Indian National Congress.

- O'Dell, Benjamin D (2014). "Beyond Bengal: Gender, Education, And The Writing Of Colonial Indian History". Victorian Literature and Culture. 42 (3): 535–551. doi:10.1017/S1060150314000138. S2CID 96476257.

- Roy, Tirthankar (Summer 2002), "Economic History and Modern India: Redefining the Link", The Journal of Economic Perspectives 16 (3): 109–130, doi:

- Sarkar, J. (2013, reprint). Economics of British India ... 3rd ed. Calcutta: M.C. Sarkar & Sons.

- Simmons, Colin (1985), "'De-Industrialization', Industrialization and the Indian Economy, c. 1850–1947", Modern Asian Studies 19 (3): 593–622, doi:

- Sinha, Mrinalini. Colonial Masculinity: The 'Manly Englishman' and the 'Effeminate Bengali' in the Late Nineteenth Century (1995).

- Strobel, Margaret. European Women and the Second British Empire (1991).

- Tirthankar, Roy (2014), "Financing the Raj: the City of London and colonial India 1858–1940", Business History 56 (6): 1024–1026, doi:

- Tomlinson, Brian Roger (1993), The Economy of Modern India, 1860–1970, New Cambridge History of India, III.3, Cambridge University Press, p. 109, ISBN 978-0-521-36230-6

- Tomlinson, Brian Roger (October 1975), "India and the British Empire, 1880–1935", Indian Economic and Social History Review 12 (4): 337–380, doi:

تأريخ وذاكرة

- Andrews, C.F. (2017). India and the Simon Report. Routledge reprint of 1930 first edition. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-315-44498-7.

- Durant, Will (2011, reprint). The case for India. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Ellis, Catriona (2009). "Education for All: Reassessing the Historiography of Education in Colonial India". History Compass. 7 (2): 363–375. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2008.00564.x.

- Gilmartin, David (2015). "The Historiography of India's Partition: Between Civilization and Modernity". The Journal of Asian Studies. 74 (1): 23–41. doi:10.1017/s0021911814001685. S2CID 67841003.

- Major, Andrea (2011). "Tall tales and true: India, historiography and British imperial imaginings". Contemporary South Asia. 19 (3): 331–332. doi:10.1080/09584935.2011.594257. S2CID 145802033.

- Mantena, Rama Sundari. The Origins of Modern Historiography in India: Antiquarianism and Philology (2012).

- Moor-Gilbert, Bart. Writing India, 1757–1990: The Literature of British India (1996) on fiction written in English.

- Mukherjee, Soumyen. "Origins of Indian Nationalism: Some Questions on the Historiography of Modern India". Sydney Studies in Society and Culture 13 (2014). online.

- Nawaz, Rafida, and Syed Hussain Murtaza. "Impact of Imperial Discourses on Changing Subjectivities in Core and Periphery: A Study of British India and British Nigeria". Perennial Journal of History 2.2 (2021): 114–130. online.

- Nayak, Bhabani Shankar. "Colonial world of postcolonial historians: reification, theoreticism, and the neoliberal reinvention of tribal identity in India". Journal of Asian and African Studies 56.3 (2021): 511–532. online.

- Parkash, Jai. "Major trends of historiography of revolutionary movement in India – Phase II". (PhD dissertation, Maharshi Dayanand University, 2013). online.

- Philips, Cyril H. ed. Historians of India, Pakistan and Ceylon (1961), reviews the older scholarship.

- Stern, Philip J (2009). "History and Historiography of the English East India Company: Past, Present, and Future". History Compass. 7 (4): 1146–1180. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2009.00617.x.

- Stern, Philip J. "Early Eighteenth-Century British India: Antimeridian or antemeridiem?". Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 21.2 (2020), pp. 1–26, focus on C.A. Bayly, Imperial Meridian online.

- Whitehead, Clive (2005). "The historiography of British imperial education policy, Part I: India". History of Education. 34 (3): 315–329. doi:10.1080/00467600500065340. S2CID 144515505.

- Winks, Robin, ed. Historiography (1999), vol. 5 in William Roger Louis, eds. The Oxford History of the British Empire.

- Winks, Robin W. The Historiography of the British Empire-Commonwealth: Trends, Interpretations and Resources (1966).

- Young, Richard Fox, ed. (2009). Indian Christian Historiography from Below, from Above, and in Between India and the Indianness of Christianity: Essays on Understanding – Historical, Theological, and Bibliographical – in Honor of Robert Eric Frykenberg.

متفرقات

- Steinberg, S. H. (1947). The Statesman's Year-Book: Statistical and Historical Annual of the States of the World for the Year 1947 (in الإنجليزية). Springer. ISSN 0081-4601.

للاستزادة

Media related to الهند البريطانية at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to الهند البريطانية at Wikimedia Commons

Quotations related to الهند البريطانية at Wikiquote

Quotations related to الهند البريطانية at Wikiquote

The Wiktionary definition of الهند البريطانية

The Wiktionary definition of الهند البريطانية- Judd, Denis. The lion and the tiger: the rise and fall of the British Raj, 1600–1947 (Oxford University Press, 2005). online

- Malone, David M., C. Raja Mohan, and Srinath Raghavan, eds. The Oxford handbook of Indian foreign policy (2015) excerpt pp 55–79.

- Simon Report (1930) vol 1, wide-ranging survey of conditions

- Editors, Charles Rivers (2016). The British Raj: The History and Legacy of Great Britain's Imperialism in India and the Indian subcontinent.

- Keith, Arthur Berriedale (1912). Responsible government in the dominions. The Clarendon press., major primary source

Year books and statistical records

- Indian Year-book for 1862: A review of social, intellectual, and religious progress in India and Ceylon (1863), ed. by John Murdoch online edition 1861 edition

- The Year-book of the Imperial Institute of the United Kingdom, the colonies and India: a statistical record of the resources and trade of the colonial and Indian possessions of the British Empire (2nd ed.). 1893. pp. 375–462.

- The Imperial Gazetteer of India (26 vol, 1908–31), highly detailed description of all of India in 1901. online edition

- Statistical abstract relating to British India, from 1895 to 1896 to 1904–05 (London, 1906) full text online,

- The Cyclopedia of India: biographical, historical, administrative, commercial (1908) business history, biographies, illustrations

- The Indian Year Book: 1914 (1914)

- The Indian Annual Register: A digest of public affairs of India regarding the nation's activities in the matters, political, economic, industrial, educational, etc. during the period 1919–1947 online

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- British India

- 1858 establishments in British India

- 1947 disestablishments in British India

- Bangladesh and the Commonwealth of Nations

- Former British colonies and protectorates in Asia

- India and the Commonwealth of Nations

- Pakistan and the Commonwealth of Nations

- States and territories disestablished in 1947

- States and territories established in 1858

- Former monarchies of India

- Former monarchies in Pakistani history

- History of Pakistan

- تاريخ الهند

- تاريخ پاكستان

- تاريخ بنجلادش

- بورما

- ولايات سابقة في آسيا

![One rupee coins showing George VI, King-Emperor, 1940 (left) and just before India's independence in 1947 (right)[د]](/w/images/thumb/9/9c/GeorgeVIKingEmperorIndia1940and1947.jpg/234px-GeorgeVIKingEmperorIndia1940and1947.jpg)