بگان

بگان

Bagan ပုဂံ پوگان | |

|---|---|

معابد بگان | |

| الإحداثيات: 21°10′N 94°52′E / 21.167°N 94.867°E | |

| البلد | بورما |

| المنطقة | منطقة مندلاي |

| تأسست | منتصف-أواخر القرن 9 |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 104 كم² (40 ميل²) |

| التعداد | |

| • العرقيات | بامار |

| • الأديان | الثرڤادا البوذية |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+6.30 (MST) |

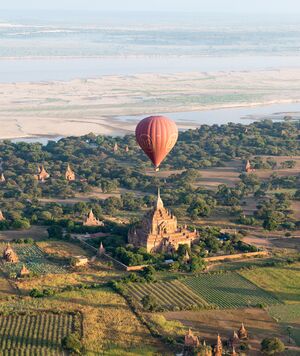

بگان (بالبورمية: ပုဂံ; MLCTS: pu.gam, IPA: [bəɡàɴ]؛ إنگليزية: Bagan؛ وسابقاً: پگان Pagan) هي مدينة قديمة تقع في منطقة مندلاي في بورما (ميانمار). ومن القرن التاسع وحتى القرن الثالث عشرـ كانت المدينة عاصمة مملكة پگان، أول مملكة توحد المناطق التي ستكشل لاحقاً ميانمار المعاصرة. وفي عز المملكة بين القرنين الحادي عشر والثالث عشر، تم تشييد أكثر من 10,000 معبد بوذي وپاگودا ودير في سهول بگان فقط، بقي منها أطلال ما يزيد على 2200 معبد وپاگودا حتى يومنا هذا.

منطقة بگان الأثرية هي عنصر الجذب الرئيسي لصناعة السياحة الوليدة في بورما. ويراها كثيرون بأن لها جاذبية مساوية لجاذبية أنگكور وات في كمبوديا.[1]

أصل الاسم

النُطق البورمي القياسي-المعاصر لبگان من الكلمة البورمية پوگان (ပုဂံ)، والمشتقة من الكلمة البورمية القديمة پوكام (ပုကမ်). اسمها بالپالية الكلاسيكية هو أريمادانا-پورا (အရိမဒ္ဒနာပူရ، وتعني حرفياً "المدينة التي تسحق الأعداء"). أسماؤها الأخرى بالپالية تشير لمناخها شديد الجفاف: تاداسا (တတ္တဒေသ، "الأرض الظمآنة")، وتامپاديپا (တမ္ပဒီပ، "البلد البرونزي").[2] كذلك ذكرت التأريخات البورمية أسماء كلاسيكية أخرى لثيري پيسايا (သီရိပစ္စယာ) وتامپاوادي (တမ္ပဝတီ).[3]

التاريخ

القرون 9 - 13

According to the royal chronicles, Bagan was founded in the second century CE, and fortified in 849 by King Pyinbya, 34th successor of the founder of early Bagan.[4] Western scholarship however holds that Bagan was founded in the mid-to-late 9th century by the Mranma (Burmans), who had recently entered the Irrawaddy valley from the Nanzhao Kingdom. It was among several competing Pyu city-states until the late 10th century when the Burman settlement grew in authority and grandeur.[5]

From 1044 to 1287, Bagan was the capital as well as the political, economic and cultural nerve center of the Bagan Empire. Over the course of 250 years, Bagan's rulers and their wealthy subjects constructed over 10,000 religious monuments (approximately 1000 stupas, 10,000 small temples and 3000 monasteries)[6] in an area of 104 km2 (40 sq mi) in the Bagan plains. The prosperous city grew in size and grandeur, and became a cosmopolitan center for religious and secular studies, specializing in Pali scholarship in grammar and philosophical-psychological (abhidhamma) studies as well as works in a variety of languages on prosody, phonology, grammar, astrology, alchemy, medicine, and legal studies.[7] The city attracted monks and students from as far as India, Sri Lanka and the Khmer Empire.

The culture of Bagan was dominated by religion. The religion of Bagan was fluid, syncretic and by later standards, unorthodox. It was largely a continuation of religious trends in the Pyu era where Theravada Buddhism co-existed with Mahayana Buddhism, Tantric Buddhism, various Hindu (Saivite, and Vaishana) schools as well as native animist (nat) traditions. While the royal patronage of Theravada Buddhism since the mid-11th century had enabled the Buddhist school to gradually gain primacy, other traditions continued to thrive throughout the Pagan period to degrees later unseen.[7]

Bagan's basic physical layout had already taken shape by the late 11th century, which was the first major period of monument building. A main strip extending for about 9 km along the east bank of the Irrawaddy emerged during this period, with the walled core (known as "Old Bagan") in the middle. 11th-century construction took place throughout this whole area and appears to have been relatively decentralized. The spread of monuments north and south of Old Bagan, according to Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung, may reflect construction at the village level, which may have been encouraged by the main elite at Old Bagan.[8]

The peak of monument building took place between about 1150 and 1200. Most of Bagan's largest buildings were built during this period. The overall amount of building material used also peaked during this phase. Construction clustered around Old Bagan, but also took place up and down the main strip, and there was also some expansion to the east, away from the Irrawaddy.[8]

By the 13th century, the area around Old Bagan was already densely packed with monuments, and new major clusters began to emerge to the east. These new clusters, like the monastic area of Minnanthu, were roughly equally distant – and equally accessible – from any part of the original strip that had been defined in the 11th century. Construction during the 13th century featured a significant increase in the building of monasteries and associated smaller monuments. Michael Aung-Thwin has suggested that the smaller sizes may indicate "dwindling economic resources" and that the clustering around monasteries may reflect growing monastic influence. Bob Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung also suggest that there was a broadening of donor activity during this period: "the religious merit that accrued from endowing an individual merit was more widely accessible", and more private individuals were endowing small monuments. As with before, this may have taken place at the village level.[8]

Both Bagan itself and the surrounding countryside offered plenty of opportunities for employment in various sectors. The prolific temple building alone would have been a huge stimulus for professions involved in their construction, such as brickmaking and masonry; gold, silver, and bronze working; carpentry and woodcarving; and ceramics. Finished temples would still need maintenance work done, so they continued to boost demand for both artisans' services and unskilled labor well after their construction. Accountants, bankers, and scribes were also necessary to manage the temple properties. These workers, especially the artisans, were paid well, which attracted many people to move to Bagan. Contemporary inscriptions indicate that "people of many linguistic and cultural backgrounds lived and worked" in Bagan during this time period. [9]

Bagan's ascendancy also coincided with a period of political and economic decline in several other nearby regions, like Dvaravati, Srivijaya, and the Chola Empire. As a result, immigrants from those places likely also ended up moving to Bagan, in addition to people moving there from within Myanmar.[9]

The Pagan Empire collapsed in 1287 due to repeated Mongol invasions (1277–1301). Recent research shows that Mongol armies may not have reached Bagan itself, and that even if they did, the damage they inflicted was probably minimal.[10] According to Michael Aung-Thwin, a more likely explanation is that the provincial governors tasked with defending against Mongol incursions were so successful that they became "the new power elite", and their capitals became the new political centers while Bagan itself became a backwater.[8] In any case, something during this period caused Bagan to decline. The city, once home to some 50,000 to 200,000 people, had been reduced to a small town, never to regain its preeminence. The city formally ceased to be the capital of Burma in December 1297 when the Myinsaing Kingdom became the new power in Upper Burma.[11][12]

القرون 14 - 19

Bagan survived into the 15th century as a human settlement,[13] and as a pilgrimage destination throughout the imperial period. A smaller number of "new and impressive" religious monuments still went up to the mid-15th century but afterward, new temple constructions slowed to a trickle with fewer than 200 temples built between the 15th and 20th centuries.[6] The old capital remained a pilgrimage destination but pilgrimage was focused only on "a score or so" most prominent temples out of the thousands such as the Ananda, the Shwezigon, the Sulamani, the Htilominlo, the Dhammayazika, and a few other temples along an ancient road. The rest—thousands of less famous, out-of-the-way temples—fell into disrepair, and most did not survive the test of time.[6]

For the few dozen temples that were regularly patronized, the continued patronage meant regular upkeep as well as architectural additions donated by the devotees. Many temples were repainted with new frescoes on top of their original Pagan era ones, or fitted with new Buddha statutes. Then came a series of state-sponsored "systematic" renovations in the Konbaung period (1752–1885), which by and large were not true to the original designs—some finished with "a rude plastered surface, scratched without taste, art or result". The interiors of some temples were also whitewashed, such as the Thatbyinnyu and the Ananda. Many painted inscriptions and even murals were added in this period.[14]

القرن 20 إلى الحاضر

Bagan, located in an active earthquake zone, had suffered from many earthquakes over the ages, with over 400 recorded earthquakes between 1904 and 1975.[15] A major earthquake occurred on 8 July 1975, reaching 8 MM in Bagan and Myinkaba, and 7 MM in Nyaung-U.[16] The quake damaged many temples, in many cases, such as the Bupaya, severely and irreparably. Today, 2229 temples and pagodas remain.[17]

Many of these damaged pagodas underwent restorations in the 1990s by the military government, which sought to make Bagan an international tourist destination. However, the restoration efforts instead drew widespread condemnation from art historians and preservationists worldwide. Critics were aghast that the restorations paid little attention to original architectural styles, and used modern materials, and that the government has also established a golf course, a paved highway, and built a 61 m (200 ft) watchtower. Although the government believed that the ancient capital's hundreds of (unrestored) temples and large corpus of stone inscriptions were more than sufficient to win the designation of UNESCO World Heritage Site,[18] the city was not so designated until 2019, allegedly mainly on account of the restorations.[19]

On 24 August 2016, a major earthquake hit Bagan, and caused major damages in nearly 400 temples. The Sulamani and Myauk Guni temples were severely damaged. The Bagan Archaeological Department began a survey and reconstruction effort with the help of the UNESCO. Visitors were prohibited from entering 33 much-damaged temples.

On 6 July 2019, Bagan was officially inscribed as a World Heritage Site by the UNESCO, 24 years after its first nomination, during the 43rd session of the World Heritage Committee.[20] Bagan became the second World Heritage Site in Myanmar, after the Ancient Cities of Pyu. As part of the criteria for the inscription of Bagan, the government had pledged to relocate existing hotels in the archaeological zone to a dedicated hotel zone by 2020.[21]

Bagan today is a main tourist destination in the country's nascent tourism industry.[22]

In March 2025, Myanmar experienced a major earthquake near Bagan. Major stupas in Bagan, including Htilominlo Pagoda and Shwezigon Pagoda, did not incur structural damage.[23]

الجغرافيا

Bagan Archaeological Zone, defined as the 13 km × 8 km (8.1 mi × 5.0 mi) area centred around Old Bagan, consisting of Nyaung U in the north and New Bagan in the south,[18] lies in the vast expanse of plains in Upper Burma on the bend of the Irrawaddy river. It is located 290 km (180 mi) south-west of Mandalay and 700 km (430 mi) north of Yangon.

المناخ

Bagan lies in the middle of the Dry Zone, the region roughly between Shwebo in the north and Pyay in the south. Unlike the coastal regions of the country, which receive annual monsoon rainfalls exceeding 2،500 mm (98 in), the dry zone gets little precipitation as it is sheltered from the rain by the Rakhine Yoma mountain range in the west.

Available online climate sources report Bagan climate quite differently.

| بيانات المناخ لـ بگان | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °س (°ف) | 32 (90) |

35 (95) |

36 (97) |

37 (99) |

33 (91) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

32 (91) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °س (°ف) | 18 (64) |

19 (66) |

22 (72) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

22 (72) |

19 (66) |

23 (72) |

| [citation needed] | |||||||||||||

أفق المدينة

العمارة

لم تنبع شهرة بگان فقط من أجل الصروح الدينية الكثيرة الموجود بها، لكن أيضاً من أجل الطراز المعماري المهيب لمبانيها، واسهاماتها في تصميمات المعابد البورمية. يقع معبد بگان ضمن طرازين معماريين: طراز معبد ستوپا-المصمت وطراز معبد گو-(ဂူ) الأجوف.

ستوپا

A stupa, also called a pagoda or chedi, is a massive structure, typically with a relic chamber inside. The Bagan stupas or pagodas evolved from earlier Pyu designs, which in turn were based on the stupa designs of the Andhra region, particularly Amaravati and Nagarjunakonda in present-day south-eastern India, and to a smaller extent to Ceylon.[25] The Bagan-era stupas in turn were the prototypes for later Burmese stupas in terms of symbolism, form and design, building techniques and even materials.[26]

Originally, a Ceylonese stupa had a hemispheric body (پالي: anda "the egg"), on which a rectangular box surrounded by a stone balustrade (harmika) was set. Extending up from the top of the stupa was a shaft supporting several ceremonial umbrellas. The stupa Buddhist cosmos: its shape symbolizes Mount Meru while the umbrella mounted on the brickwork represents the world's axis.[27] The brickwork pediment was often covered in stucco and decorated in relief. Pairs or series of ogres as guardian figures ('bilu') were a favourite theme in the Bagan period.[28]

The original Indic design was gradually modified first by the Pyu, and then by Burmans at Bagan where the stupa gradually developed a longer, cylindrical form. The earliest Bagan stupas such as the Bupaya (c. 9th century) were the direct descendants of the Pyu style at Sri Ksetra. By the 11th century, the stupa had developed into a more bell-shaped form in which the parasols morphed into a series of increasingly smaller rings placed on one top of the other, rising to a point. On top the rings, the new design replaced the harmika with a lotus bud. The lotus bud design then evolved into the "banana bud", which forms the extended apex of most Burmese pagodas. Three or four rectangular terraces served as the base for a pagoda, often with a gallery of terra-cotta tiles depicting Buddhist jataka stories. The Shwezigon Pagoda and the Shwesandaw Pagoda are the earliest examples of this type.[27] Examples of the trend toward a more bell-shaped design gradually gained primacy as seen in the Dhammayazika Pagoda (late 12th century) and the Mingalazedi Pagoda (late 13th century).[29]

المعابد الجوفاء

In contrast to the stupas, the hollow gu-style temple is a structure used for meditation, devotional worship of the Buddha and other Buddhist rituals. The gu temples come in two basic styles: "one-face" design and "four-face" design—essentially one main entrance and four main entrances. Other styles such as five-face and hybrids also exist. The one-face style grew out of 2nd century Beikthano, and the four-face out of 7th century Sri Ksetra. The temples, whose main features were the pointed arches and the vaulted chamber, became larger and grander in the Bagan period.[30]

إبداعات

Although the Burmese temple designs evolved from Indic, Pyu (and possibly Mon) styles, the techniques of vaulting seem to have developed in Bagan itself. The earliest vaulted temples in Bagan date to the 11th century, while the vaulting did not become widespread in India until the late 12th century. The masonry of the buildings shows "an astonishing degree of perfection", where many of the immense structures survived the 1975 earthquake more or less intact.[27] (Unfortunately, the vaulting techniques of the Bagan era were lost in the later periods. Only much smaller gu style temples were built after Bagan. In the 18th century, for example, King Bodawpaya attempted to build the Mingun Pagoda, in the form of spacious vaulted chambered temple but failed as craftsmen and masons of the later era had lost the knowledge of vaulting and keystone arching to reproduce the spacious interior space of the Bagan hollow temples.[26])

Another architectural innovation originated in Bagan is the Buddhist temple with a pentagonal floor plan. This design grew out of hybrid (between one-face and four-face designs) designs. The idea was to include the veneration of the Maitreya Buddha, the future and fifth Buddha of this era, in addition to the four who had already appeared. The Dhammayazika and the Ngamyethna Pagoda are examples of the pentagonal design.[27]

مواقع ثقافية بارزة

| الاسم | الصورة | أُنشِأت | الراعي | ملاحظات |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| معبد أنادا |

|

1105 | الملك كيانسيتا | واحد من أشهر معابد بگان |

| Bupaya Pagoda |

|

ح. 850 | الملك پيوساوتي | على طراز [[پيو (شعب)|پيو؛ المعبد الأصلي من القرن التاسع وتدمر بعد زلزال 1975؛ أعيد بناؤه مجدداً، وهو حالياً مطلي بالذهب |

| Dhammayangyi Temple |

|

1167–1170 | الملك ناراتو | أكبر معبد في بگان |

| Dhammayazika Pagoda |

|

1196–1198 | الملك سيتو | |

| معبد گاوداوپالين |

|

ح. 1211–1235 | الملك سيتو الثاني والملك هتيلومينلو | |

| Gubyaukgyi Temple (Wetkyi-in) | أوائل القرن 13 | الملك كيانسيتا | ||

| Gubyaukgyi Temple (Myinkaba) |

|

1113 | الأمير يازاكومار | |

| معبد هتيلومينلو |

|

1218 | الملك هتيلومينلو | ثلاث مخازن وارتفاعه 46 متر |

| Lawkananda Pagoda |

|

c. 1044–1077 | الملك أناوراتا | |

| معبد ماهابودي | ح. 1218 | الملك هتيلومينلو | Smaller replica of the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya | |

| معبد مانوها |

|

1067 | الملك مانوها | |

| Mingalazedi Pagoda |

|

1268–1274 | الملك ناراتيهاپاتا | |

| معبد مينينگو |

|

|||

| Myazedi inscription |

|

1112 | الأمير يازاكومار | "Rosetta Stone of Burma" with inscriptions in four languages: Pyu, Old Mon, Old Burmese and Pali |

| Nanpaya Temple |

|

c. 1160–1170 | Hindu temple in Mon style; believed to be either Manuha's old residence or built on the site | |

| Nathlaung Kyaung Temple |

|

c. 1044–1077 | Hindu temple | |

| Payathonzu Temple |

|

c. 1200 | in Mahayana and Tantric-styles | |

| Seinnyet Nyima Pagaoda and Seinnyet Ama Pagoda | c. 11th century | |||

| Shwegugyi Temple |

|

1131 | King Sithu I | Sithu I was assassinated here; known for its arched windows |

| Shwesandaw Pagoda | c. 1070 | King Anawrahta | ||

| Shwezigon Pagoda |

|

1102 | King Anawrahta and King Kyansittha | |

| Sulamani Temple |

|

1183 | King Sithu II | |

| Tharabha Gate |

|

c. 1020 | King Kunhsaw Kyaunghpyu and King Kyiso | The only remaining part of the old walls; radiocarbon dated to c. 1020[31] |

| Thatbyinnyu Temple |

|

c. 1150 | Sithu I | At 61 meters, the tallest temple in Bagan |

| Tuywindaung Pagoda | Anawrahta |

The walled core of "Old Bagan"

The 140-hectare core on the riverbank is surrounded by three walls. A fourth wall, on the western side, may have once existed before being washed away by the river at some point. The Irrawaddy has certainly eroded at least some parts of the city, since there are "buildings collapsing into the river both upstream and downstream from the walled core".[8]

The walled core called "Old Bagan" takes up only a tiny fraction of the 8,000-hectare area where monuments are found. It is also much smaller than the walled areas of major Pyu cities (the largest, Śrī Kṣetra or Thayekittaya, has a walled area of 1,400 hectares). Altogether, this suggests that "'Old Bagan' represents an elite core, not an urban boundary".[8]

المواقع النائية

أوتين تاون

An important outlying site is at Otein Taung, 2 km south of the Ananda temple in the walled city of Old Bagan. The name "Otein Taung" is a descriptive name meaning "pottery hill"; there is another Otein Taung on the north side of Beikthano. The site of Otein Taung at Bagan actually consists of two different mounds separated by 500 meters. Both are "covered with dense layers of fragmented pottery, and with scatters of potsherds visible around and between them". Local farm fields for crops like maize come right up to the edges of the mounds, and goats and cattle commonly graze on them.[8]

Besides the mounds, there are also about 40 small monuments at Otein Taung, mostly dated to the 13th century. Several of these are clustered around a monastery on the south side of the western mound. There is also a group of monuments arranged in a straight line, which may represent a property boundary or road. Another cluster exists south of the eastern mound, and then there are also randomly scattered monuments in the area between the mounds. Finally, there is a large temple between the two mounds, which was probably built in the 12th century. This temple was restored in 1999.[8]

Otein Taung was excavated by a team led by Bob Hudson and Nyein Lwin in 1999 and 2000. Excavation revealed layers of potash with a fine texture, suggesting that most of the fuel was provided by bamboo and other grasses. Also found were small charcoal fragments, preserved burnt bamboo filaments, and some animal bones and pigs' teeth. Based on radiocarbon dating, Otein Taung dates from at least the 9th century, which is well before recorded history at Bagan.[8]

The sprinkler pot, or kendi, is a very characteristic type of pottery from medieval Myanmar, and over 50 spouts and necks belonging to them were found by archaeologists at Otein Taung. These were all straight, in contrast to the bent spouts found at Beikthano. Also found at Otein Taung are earthenware tubes, about 60 cm long and 40 cm in diameter. Similar pipes have been found at Old Bagan, and they are thought to have been part of toilets.[8]

It is not clear whether Otein Taung represents a large-scale pottery production site or "a huge, and for Bagan unique, residential midden". Archaeologists did not find any "slumps characteristic of overfiring in a stoneware kiln, [or] any large brick or earth structures suggesting a pottery kiln", but several "earthenware anvils" were found at the site, as well as a 10-cm-long clay tube that may have been used as a stamp for decorating pots. The anvils are common potters' tools in South and Southeast Asia: they are held inside a pot while the outside is beaten with a paddle.[8]

If Otein Taung was used as a pottery production site, then it would have had good access to natural clay resources: the Bagan area has clayey subsoil that is "still mined today for brickmaking". There are four tanks within 500 m of Otein Taung that may have originated as clay pits.[8]

المتاحف

- The Bagan Archaeological Museum: The only museum in the Bagan Archaeological Zone. The three-story museum houses a number of rare Bagan period objects including the original Myazedi inscriptions, the Rosetta Stone of Burma.

- Anawrahta's Palace: It was rebuilt in 2003 based on the extant foundations at the old palace site.[32] But the palace above the foundation is completely conjectural.

المدن الشقيقة

الهامش

- ^ http://www.economist.com/news/special-report/21578171-why-investors-still-need-proceed-caution-promiseand-pitfalls Business: The promise—and the pitfalls

- ^ Than Tun 1964: 117–118

- ^ Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 139–141

- ^ Harvey 1925: 18

- ^ Lieberman 2003: 90–91

- ^ أ ب ت Stadtner 2011: 216

- ^ أ ب Lieberman 2003: 115–116

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س Hudson, Bob; Nyein Lwin; Win Maung (2001). "The Origins of Bagan: New Dates and Old Inhabitants". Asian Perspectives. 40 (1): 48–74. doi:10.1353/asi.2001.0009. hdl:10125/17144. JSTOR 42928487. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ أ ب Aung-Thwin, Michael (2005). The mists of Rāmañña: The Legend that was Lower Burma (PDF). Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2886-0. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Lieberman 2003: 119–120

- ^ Htin Aung 1967: 74

- ^ Than Tun 1959: 119–120

- ^ Aung-Thwin 1985: 196–197

- ^ Stadtner 2011: 217

- ^ Unesco 1976: ix

- ^ Ishizawa and Kono 1989: 114

- ^ Köllner, Bruns 1998: 117

- ^ أ ب Unesco 1996

- ^ Tourtellot 2004

- ^ "Myanmar's temple city Bagan awarded UNESCO World Heritage status". CNA (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 2019-07-07. Retrieved 2019-07-07.

- ^ "Bagan named UNESCO World Heritage Site". The Myanmar Times (in الإنجليزية). 7 July 2019. Archived from the original on 2021-07-29. Retrieved 2019-07-07.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةte - ^ "Recent earthquake leaves pagodas and stupas in Bagan unaffected". Global New Light Of Myanmar (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2025-03-31. Retrieved 2025-04-14.

- ^ "Weather for Bagan". www.holidaycheck.com. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- ^ Aung-Thwin 2005: 26–31

- ^ أ ب Aung-Thwin 2005: 233–235

- ^ أ ب ت ث Köllner, Bruns 1998: 118–120

- ^ Falconer, J.; Moore, E.; Tettoni, L. I. (2000). Burmese design and architecture. Hong Kong: Periplus. ISBN 9625938826.

- ^ Aung-Thwin 2005: 210–213

- ^ Aung-Thwin 2005: 224–225

- ^ Aung-Thwin 2005: 38

- ^ Ministry of Culture

- ^ أ ب Pan Eiswe Star and Soe Than Linn 2010

وصلات خارجية

- Pictorial Guide to Pagan. 2nd ed. Rangoon: Ministry of Culture, 1975.

- Pagan - Art and Architecture of Old Burma Paul Strachan 1989, Kiscadale, Arran, Scotland.

- Glimpses of Glorious Pagan Department of History, University of Rangoon, The Universities Press 1986.

- Bagan Map. DPS Online Maps.

- Myanmar (Burma) - Photo Gallery

- All about Bagan (english version)

- All about Bagan (spanish version)

- All about Bagan (mobile version)

- Free travel images of Bagan

- The Life of the Buddha in 80 Scenes, Ananda Temple Charles Duroiselle, Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report, Delhi, 1913–14

- The Art and Culture of Burma - the Pagan Period Dr. Richard M. Cooler, جامعة إلينوي الشمالية

- Asian Historical Architecture: Bagan Prof. Robert D. Fiala, Concordia University, Nebraska

- Buddhist Architecture at Bagan Bob Hudson, University of Sydney, Australia

- Photographs of temples and paintings of Bagan Part 1 and Part 2

بگان

| ||

| سبقه لم يكن هناك عاصمة قومية |

عاصمة بورما 23 ديسمبر 849 – 17 ديسمبر 1297 |

تبعه Myinsaing, Mekkhaya, Pinle Martaban Launggyet |

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing بورمية-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2012

- Articles containing پالي-language text

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- عواصم بلدات في بورما

- تأسيسات القرن 9

- تاريخ بورما

- معابد بوذية في بورما

- أماكن مأهولة في منطقة مندلاي

- أماكن حج بوذية

- بگا

- فن وثقافة بوذية

- معالم سياحية في بورما

- متعلقة بالمكتبة الرقمية الدولية