بالتيمور

بالتيمور (إنگليزية: Baltimore، /ˈbɔːltɪmɔːr/ BAWL-tim-or، محلياً: /ˌbɔːldɪˈmɔːr/ BAWL-dih-MOR أو /ˈbɔːlmər/ BAWL-mər[11])، هي أكثر المدن اكتظاظاً بالسكان في ولاية مريلاند الأمريكية. بتعداد سكان 585.708 نسمة عام 2020، تحتل بالتيمور الترتيب رقم 30 كأكثر المدن اكتظاظاً بالسكان في الولايات المتحدة.[12] عام 1851 بالتيمور عُينت كمدينة مستقلة بحسب دستور مريلاند[أ]، واليوم هي أكثر المدن المستقلة اكتظاظاً بالسكان في البلاد. بحسب تعداد 2020، كان عدد سكان منطقة بالتيمور الكبرى 2.838.327 نسمة، مما يجعلها في الترتيب 20 كأكبر منطقة احصائية في البلاد.[13] عند دمجها مع منطقة واشنطن العاصمة الكبرى الأكبر، منطقة واشنطن-بالتتيمور الاحصائية المجموعة، بلغ عدد سكانها 9.973.383 نسمة في تعداد 2020.[13]

قبل الاستعمار الأوروبي، كانت شعوب سسكويهانوك الأصلية تستخدم منطقة بالتيمور كأراضي للصيد، والذين كانوا يستوطنون بشكل أساسي الأراضي الواقعة إلى الشمال الغربي من الموقع الذي بُنيت عليه المدينة الحالية.[14] عام 1706 أسس مستعمرون من مقاطعة مريلاند ميناء بالتيمور لدعم تجارة التبغ مع أوروبا، وأسسوا بلدة بالتيمور عام 1729. طُرحت أول مطبعة وصحف إلى بالتيمور بواسطة نيكولاس هاسيلباخ ووليام جودارد على التوالي، في منتصف القرن الثامن عشر.

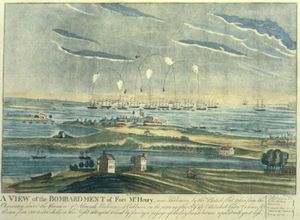

كانت معركة بالتيمور معركة محورية أثناء حرب 1812، وبلغت ذروتها في القصف البريطانية الفاشل لحصن ماكهنري، وخلالهاكتب فرانسيس سكوت كي قصيدة "الراية ذات النجوم المتلألئة والتي اختيرت في النهاية النشيد الوطني الأمريكي عام 1931.[15] أثناء أعمال شغب شارع برات 1861، كانت المدينة موقعًا لبعض أقدم أعمال العنف المرتبطة بالحرب الأهلية الأمريكية.

عام 1830، بُني خط سكة حديد بالتيمور-أوهايو، أقدم سكة حديد في الولايات المتحدة، الذي عزز مكانة بالتيمور كمركز رئيسي للنقل، مما أعطى المنتجين في الغرب الأوسط و[[أپالاشيا] ] الوصول إلى ميناء المدينة. كان إينر هاربور في بالتيمور ثاني أكبر ميناء دخول بالنسبة للمهاجرين إلى الولايات المتحدة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، كانت بالتيمور مركزًا رئيسيًا للتصنيع.[16] بعد تراجع الصناعة الثقيلة التي كانت بمثابة النشاط الصناعي الرئيسي بالمدينة، وإعادة هيكلة صناعة السكك الحديدية، تحولت بالتيمور إلى الاقتصاد الخدمي. ومن أكبر أرباب الأعمال في المدينة مستشفى جونز هوپكنز وجامعة جونز هوپكنز.[17]

بالتيمور والمنطقة المحيطة بها مقر لعدد من المنظمات والوكالات الحكومية الرئيسية، بما في ذلك NAACP، ABET، الاتحاد الوطني للمكفوفين، خدمات الإغاثة الكاثوليكية ومؤسسة آني إي كيسي والإغاثة العالمية ومراكز الرعاية الطبية والخدمات الطبية وإدارة الضمان الاجتماعي. كما تضم المدينة ايضاً فريق بالتيمور أوريولز الذي يلعب في دوري البيسبول الرئيسي وبالتيمور رافينز الذي يلعب الدوري الوطني لكرة القدم الأمريكية.

يتمتع العديد من أحياء بالتيمور بتاريخ غني. تضم المدينة مجموعة من أقدم مناطق السجل التاريخي الوطني للولاية، بما في ذلك فلز بوينت، فدرال هيل، وماونت فرنون. أُضيفت هذه المناطق إلى السجل الوطني بين عامي 1969 و1971، بعد فترة وجيزة من إقرار تشريع الحفاظ التاريخي. يوجد في بالتيمور عدد من التماثيل والنصب العامة الفردية أكثر من أي مدينة أخرى في البلاد.[18] تم تصنيف ما يقرب من ثلث مباني المدينة (أكثر من 65.000) كمباني تاريخية في السجل الوطن، ما يعتبر أكثر من أي مدينة أمريكية أخرى.[19][20] يوجد في بالتيمور 66 مقاطعة تاريخية وطنية و33 مقاطعة تاريخية محلية.[19] السجلات التاريخية لحكومة بالتيمور محفوظة في أرشيفات مدينة بالتيمور.

أصل الاسم

The city is named after Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore,[21] an English politician and lawyer who was a founding proprietor of the Province of Maryland.[22][23] The Calverts took the title Barons Baltimore from Baltimore Manor, an estate they were granted by the Crown in County Longford as part of the plantations of Ireland.[23][24] Baltimore is an anglicization of Baile an Tí Mhóir, meaning "town of the big house" in Irish.[23]

التاريخ

ما قبل الاستيطان

The Baltimore area had been inhabited by Native Americans since at least the 10th millennium BC, when Paleo-Indians first settled in the region.[25] One Paleo-Indian site and several Archaic period and Woodland period archaeological sites have been identified in Baltimore, including four from the Late Woodland period.[25] In December 2021, several Woodland period Native American artifacts were found in Herring Run Park in northeast Baltimore, dating 5,000 to 9,000 years ago. The finding followed a period of dormancy in Baltimore City archaeological findings which had persisted since the 1980s.[26] During the Late Woodland period, the archaeological culture known as the Potomac Creek complex resided in the area from Baltimore south to the Rappahannock River in present-day Virginia.[27]

القرن السابع عشر

In the early 1600s, the immediate Baltimore vicinity was sparsely populated, if at all, by Native Americans. The Baltimore County area northward was used as hunting grounds by the Susquehannock living in the lower Susquehanna River valley. This Iroquoian-speaking people "controlled all of the upper tributaries of the Chesapeake" but "refrained from much contact with Powhatan in the Potomac region" and south into Virginia.[28] Pressured by the Susquehannock, the Piscataway tribe, an Algonquian-speaking people, stayed well south of the Baltimore area and inhabited primarily the north bank of the Potomac River in what are now Charles and southern Prince George's counties in the coastal areas south of the Fall Line.[29][30][31]

European colonization of Maryland began in earnest with the arrival of the merchant ship The Ark carrying 140 colonists at St. Clement's Island in the Potomac River on March 25, 1634.[32] Europeans then began to settle the area further north, in what is now Baltimore County.[33] Since Maryland was a colony, Baltimore's streets were named to show loyalty to the mother country, e.g. King, Queen, King George and Caroline streets.[34] The original county seat, known today as Old Baltimore, was located on Bush River within the present-day Aberdeen Proving Ground.[35][36][37] The colonists engaged in sporadic warfare with the Susquehannock, whose numbers dwindled primarily from new infectious diseases, such as smallpox, endemic among the Europeans.[33] In 1661 David Jones claimed the area known today as Jonestown on the east bank of the Jones Falls stream.[38]

القرن 18

The colonial General Assembly of Maryland created the Port of Baltimore at old Whetstone Point, now Locust Point, in 1706 for the tobacco trade. The Town of Baltimore, on the west side of the Jones Falls, was founded on August 8, 1729, when the Governor of Maryland signed an act allowing "the building of a Town on the North side of the Patapsco River". Surveyors began laying out the town on January 12, 1730. By 1752 the town had just 27 homes, including a church and two taverns.[34] Jonestown and Fells Point had been settled to the east. The three settlements, covering 60 acre (24 ha), became a commercial hub, and in 1768 were designated as the county seat.[39]

The first printing press was introduced to the city in 1765 by Nicholas Hasselbach, whose equipment was later used in the printing of Baltimore's first newspapers, The Maryland Journal and The Baltimore Advertiser, first published by William Goddard in 1773.[40][41][42]

Baltimore grew swiftly in the 18th century, its plantations producing grain and tobacco for sugar-producing colonies in the Caribbean. The profit from sugar encouraged the cultivation of cane in the Caribbean and the importation of food by planters there.[43] Since Baltimore was the county seat, a courthouse was built in 1768 to serve both the city and county. Its square was a center of community meetings and discussions.

Baltimore established its public market system in 1763.[44] Lexington Market, founded in 1782, is one of the oldest continuously operating public markets in the United States today.[45] Lexington Market was also a center of slave trading. Enslaved Black people were sold at numerous sites through the downtown area, with sales advertised in The Baltimore Sun.[46] Both tobacco and sugar cane were labor-intensive crops.

In 1774, Baltimore established the first post office system in what became the United States,[47] and the first water company chartered in the newly independent nation, Baltimore Water Company, 1792.[48][49]

Baltimore played a part in the American Revolution. City leaders such as Jonathan Plowman Jr. led many residents to resist British taxes, and merchants signed agreements refusing to trade with Britain.[50] The Second Continental Congress met in the Henry Fite House from December 1776 to February 1777, effectively making the city the capital of the United States during this period.[51]

Baltimore, Jonestown, and Fells Point were incorporated as the City of Baltimore in 1796–1797.

القرن 19

The city remained a part of surrounding Baltimore County and continued to serve as its county seat from 1768 to 1851, after which it became an independent city.[54]

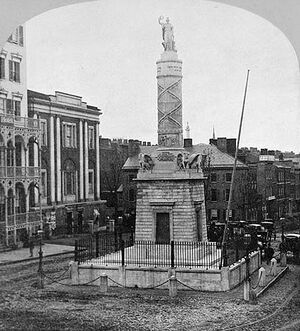

The British bombardment of Baltimore in 1814 inspired the U.S. national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner", and the construction of the Battle Monument, which became the city's official emblem. A distinctive local culture started to take shape, and a unique skyline peppered with churches and monuments developed. Baltimore acquired its moniker "The Monumental City" after an 1827 visit to Baltimore by President John Quincy Adams. At an evening function, Adams gave the following toast: "Baltimore: the Monumental City—May the days of her safety be as prosperous and happy, as the days of her dangers have been trying and triumphant."[55][56]

Baltimore pioneered the use of gas lighting in 1816, and its population grew rapidly in the following decades, with concomitant development of culture and infrastructure. The construction of the federally funded National Road, which later became part of U.S. Route 40, and the private Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B. & O.) made Baltimore a major shipping and manufacturing center by linking the city with major markets in the Midwest. By 1820 its population had reached 60,000, and its economy had shifted from its base in tobacco plantations to sawmilling, shipbuilding, and textile production. These industries benefited from war but successfully shifted into infrastructure development during peacetime.[57]

Baltimore had one of the worst riots of the antebellum South in 1835, when bad investments led to the Baltimore bank riot.[58] It was these riots that led to the city being nicknamed "Mobtown".[59] Soon after the city created the world's first dental college, the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery, in 1840, and shared in the world's first telegraph line, between Baltimore and Washington, D.C., in 1844.

Maryland, a slave state with limited popular support for secession, especially in the three counties of Southern Maryland, remained part of the Union during the American Civil War, following the 55–12 vote by the Maryland General Assembly against secession. In February 1861, a plot in Baltimore to assassinate President-elect Abraham Lincoln was foiled by agents of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency.[60] Lincoln was able to pass through the city unnoticed, and arrived in Washington to be inaugurated a little more than a week later.[60] Later, the Union's strategic occupation of the city in 1861 ensured Maryland would not further consider secession.[61][62] The Union's capital of Washington, D.C. was well-situated to impede Baltimore and Maryland's communication or commerce with the Confederacy. Baltimore experienced some of the first casualties of Civil War on April 19, 1861, when Union Army soldiers en route from President Street Station to Camden Yards clashed with a secessionist mob in the Pratt Street riot.

In the midst of the Long Depression that followed the Panic of 1873, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad company attempted to lower its workers' wages, leading to strikes and riots in the city and beyond. Strikers clashed with the National Guard, leaving 10 dead and 25 wounded.[63] The beginnings of settlement movement work in Baltimore were made early in 1893, when Rev. Edward A. Lawrence took up lodgings with his friend Frank Thompson, in one of the Winans tenements, the Lawrence House being established shortly thereafter at 814-816 West Lombard Street.[64][65]

القرن العشرون

On February 7, 1904, the Great Baltimore Fire destroyed over 1,500 buildings in 30 hours, leaving more than 70 blocks of the downtown area burned to the ground. Damages were estimated at $150 million in 1904 dollars.[66] As the city rebuilt during the next two years, lessons learned from the fire led to improvements in firefighting equipment standards.[67]

Baltimore lawyer Milton Dashiell advocated for an ordinance to bar African-Americans from moving into the Eutaw Place neighborhood in northwest Baltimore. He proposed to recognize majority white residential blocks and majority black residential blocks and to prevent people from moving into housing on such blocks where they would be a minority. The Baltimore Council passed the ordinance, and it became law on December 20, 1910, with Democratic Mayor J. Barry Mahool's signature.[68] The Baltimore segregation ordinance was the first of its kind in the United States. Many other southern cities followed with their own segregation ordinances, though the US Supreme Court ruled against them in Buchanan v. Warley (1917).[69]

The city grew in area by annexing new suburbs from the surrounding counties through 1918, when the city acquired portions of Baltimore County and Anne Arundel County.[70] A state constitutional amendment, approved in 1948, required a special vote of the citizens in any proposed annexation area, effectively preventing any future expansion of the city's boundaries.[71] Streetcars enabled the development of distant neighborhoods areas such as Edmonson Village whose residents could easily commute to work downtown.[72]

Driven by migration from the deep South and by white suburbanization, the relative size of the city's black population grew from 23.8% in 1950 to 46.4% in 1970.[73] Encouraged by real estate blockbusting techniques, recently settled white areas rapidly became all-black neighborhoods, in a rapid process which was nearly total by 1970.[74]

The Baltimore riot of 1968, coinciding with uprisings in other cities, followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968. Public order was not restored until April 12, 1968. The Baltimore uprising cost the city an estimated $10 million (US$ 67 million in 2022). A total of 12,000 Maryland National Guard and federal troops were ordered into the city.[75] The city experienced challenges again in 1974 when teachers, municipal workers, and police officers conducted strikes.[76]

By the beginning of the 1970s, Baltimore's downtown area, known as the Inner Harbor, had been neglected and was occupied by a collection of abandoned warehouses. The nickname "Charm City" came from a 1975 meeting of advertisers seeking to improve the city's reputation.[77][78] Efforts to redevelop the area started with the construction of the Maryland Science Center, which opened in 1976, the Baltimore World Trade Center (1977), and the Baltimore Convention Center (1979). Harborplace, an urban retail and restaurant complex, opened on the waterfront in 1980, followed by the National Aquarium, Maryland's largest tourist destination, and the Baltimore Museum of Industry in 1981.

In 1995, the city opened the American Visionary Art Museum on Federal Hill. During the epidemic of HIV/AIDS in the United States, Baltimore City Health Department official Robert Mehl persuaded the city's mayor to form a committee to address food problems. The Baltimore-based charity Moveable Feast grew out of this initiative in 1990.[79][80][81]

In 1992, the Baltimore Orioles baseball team moved from Memorial Stadium to Oriole Park at Camden Yards, located downtown near the harbor. Pope John Paul II held an open-air mass at Camden Yards during his papal visit to the United States in October 1995. Three years later the Baltimore Ravens football team moved into M&T Bank Stadium next to Camden Yards.[82]

Baltimore has had a high homicide rate for several decades, peaking in 1993, and again in 2015.[83][84] These deaths have taken an especially severe toll within the black community.[85] Following the death of Freddie Gray in April 2015, the city experienced major protests and international media attention, as well as a clash between local youth and police that resulted in a state of emergency declaration and a curfew.[86]

القرن 21

Baltimore has seen the reopening of the Hippodrome Theatre in 2004,[87] the opening of the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture in 2005, and the establishment of the National Slavic Museum in 2012. On April 12, 2012, Johns Hopkins held a dedication ceremony to mark the completion of one of the United States' largest medical complexes – the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore – which features the Sheikh Zayed Cardiovascular and Critical Care Tower and The Charlotte R. Bloomberg Children's Center. The event, held at the entrance to the $1.1 billion 1.6 million-square-foot-facility, honored the many donors including Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan, first president of the United Arab Emirates, and Michael Bloomberg.[88][89]

In September 2016, the Baltimore City Council approved a $660 million bond deal for the $5.5 billion Port Covington redevelopment project championed by Under Armour founder Kevin Plank and his real estate company Sagamore Development. Port Covington surpassed the Harbor Point development as the largest tax-increment financing deal in Baltimore's history and among the largest urban redevelopment projects in the country.[90] The waterfront development that includes the new headquarters for Under Armour, as well as shops, housing, offices, and manufacturing spaces is projected to create 26,500 permanent jobs with a $4.3 billion annual economic impact.[91] Goldman Sachs invested $233 million into the redevelopment project.[92]

In the early hours of March 26, 2024, the city's 1.6-ميل-long (2.6 km) Francis Scott Key Bridge, which constituted a southeast portion of the Baltimore Beltway, was struck by a container ship and completely collapsed. A major rescue operation was launched with US authorities attempting to rescue people in the water.[93] Eight construction workers, who were working on the bridge at the time, fell into the Patapsco River.[94] Two people were rescued from the water,[95] and the bodies of the remaining six were all found by May 7.[96] Replacement of the bridge was estimated in May 2024 at a cost approaching $2 billion for a fall 2028 completion.[97]

الجغرافيا

Baltimore is in north-central Maryland on the Patapsco River, close to where it empties into the Chesapeake Bay. Baltimore is located on the fall line between the Piedmont Plateau and the Atlantic coastal plain, which divides Baltimore into "lower city" and "upper city". Baltimore's elevation ranges from sea level at the harbor to 480 أقدام (150 m) in the northwest corner near Pimlico.[6]

In the 2010 census, Baltimore has a total area of 92.1 ميل مربع (239 km2), of which 80.9 sq mi (210 km2) is land and 11.1 sq mi (29 km2) is water.[98] The total area is 12.1 percent water.

Baltimore is almost surrounded by Baltimore County, but is politically independent of it. It is bordered by Anne Arundel County to the south.

Cityscape

Architecture

Baltimore exhibits examples from each period of architecture over more than two centuries, and work from architects such as Benjamin Latrobe, George A. Frederick, John Russell Pope, Mies van der Rohe, and I. M. Pei.

Baltimore is rich in architecturally significant buildings in a variety of styles. The Baltimore Basilica (1806–1821) is a neoclassical design by Benjamin Latrobe, and one of the oldest Catholic cathedrals in the United States. In 1813, Robert Cary Long Sr. built for Rembrandt Peale the first substantial structure in the United States designed expressly as a museum. Restored, it is now the Municipal Museum of Baltimore, or popularly the Peale Museum.

The McKim Free School was founded and endowed by John McKim. The building was erected by his son Isaac in 1822 after a design by William Howard and William Small. It reflects the popular interest in Greece when the nation was securing its independence and a scholarly interest in recently published drawings of Athenian antiquities.

The Phoenix Shot Tower (1828), at 234.25 أقدام (71.40 m) tall, was the tallest building in the United States until the time of the Civil War, and is one of few remaining structures of its kind.[99] It was constructed without the use of exterior scaffolding. The Sun Iron Building, designed by R.C. Hatfield in 1851, was the city's first iron-front building and was a model for a whole generation of downtown buildings. Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church, built in 1870 in memory of financier George Brown, has stained glass windows by Louis Comfort Tiffany and has been called "one of the most significant buildings in this city, a treasure of art and architecture" by Baltimore magazine.[100][101]

The 1845 Greek Revival-style Lloyd Street Synagogue is one of the oldest synagogues in the United States. The Johns Hopkins Hospital, designed by Lt. Col. John S. Billings in 1876, was a considerable achievement for its day in functional arrangement and fireproofing.

I.M. Pei's World Trade Center (1977) is the tallest equilateral pentagonal building in the world at 405 أقدام (123 m) tall.[102]

The Harbor East area has seen the addition of two new towers which have completed construction: a 24-floor tower that is the new world headquarters of Legg Mason, and a 21-floor Four Seasons Hotel complex.

The streets of Baltimore are organized in a grid and spoke pattern, lined with tens of thousands of rowhouses. The mix of materials on the face of these rowhouses also give Baltimore its distinct look. The rowhouses are a mix of brick and formstone facings, the latter a technology patented in 1937 by Albert Knight. John Waters characterized formstone as "the polyester of brick" in a 30-minute documentary film, Little Castles: A Formstone Phenomenon.[103] In The Baltimore Rowhouse, Mary Ellen Hayward and Charles Belfoure considered the rowhouse as the architectural form defining Baltimore as "perhaps no other American city".[104] In the mid-1790s, developers began building entire neighborhoods of the British-style rowhouses, which became the dominant house type of the city early in the 19th century.[105]

Oriole Park at Camden Yards is a Major League Baseball park, which opened in 1992 and was built as a retro style baseball park. Along with the National Aquarium, Camden Yards have helped revive the Inner Harbor area from what once was an exclusively industrial district full of dilapidated warehouses into a bustling commercial district full of bars, restaurants, and retail establishments.

After an international competition, the University of Baltimore School of Law awarded the German firm Behnisch Architekten 1st prize for its design, which was selected for the school's new home. After the building's opening in 2013, the design won additional honors including an ENR National "Best of the Best" Award.[106]

Baltimore's newly rehabilitated Everyman Theatre was honored by the Baltimore Heritage at the 2013 Preservation Awards Celebration in 2013. Everyman Theatre will receive an Adaptive Reuse and Compatible Design Award as part of Baltimore Heritage's 2013 historic preservation awards ceremony. Baltimore Heritage is Baltimore's nonprofit historic and architectural preservation organization, which works to preserve and promote Baltimore's historic buildings and neighborhoods.[107]

Tallest buildings

| Rank | Building | Height | Floors | Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Transamerica Tower (formerly the Legg Mason Building, originally built as the U.S. Fidelity and Guarantee Co. Building)[108] | 529 أقدام (161 m) | 40 | 1973 | [109] |

| 2 | Bank of America Building (originally built as Baltimore Trust Building, later Sullivan, Mathieson, Md. Nat. Bank, NationsBank Bldgs.) | 509 أقدام (155 m) | 37 | 1929 | [110] |

| 3 | 414 Light Street | 500 أقدام (152 m) | 44 | 2018 | [111] |

| 4 | William Donald Schaefer Tower (originally built as the Merritt S. & L. Tower) | 493 أقدام (150 m) | 37 | 1992 | [112] |

| 5 | Commerce Place (Alex. Brown & Sons/Deutsche Bank Tower) | 454 أقدام (138 m) | 31 | 1992 | [113] |

| 6 | Baltimore Marriott Waterfront Hotel | 430 أقدام (131 m) | 32 | 2001 | [114] |

| 7 | 100 East Pratt Street (originally built as the I.B.M. Building) | 418 أقدام (127 m) | 28 | 1975/1992 | [115] |

| 8 | Baltimore World Trade Center | 405 أقدام (123 m) | 28 | 1977 | [116] |

| 9 | Tremont Plaza Hotel | 395 أقدام (120 m) | 37 | 1967 | [117] |

| 10 | Charles Towers South | 385 أقدام (117 m) | 30 | 1969 | [118] |

Neighborhoods

Baltimore is officially divided into nine geographical regions: North, Northeast, East, Southeast, South, Southwest, West, Northwest, and Central, with each district patrolled by a respective Baltimore Police Department. Interstate 83 and Charles Street down to Hanover Street and Ritchie Highway serve as the east–west dividing line and Eastern Avenue to Route 40 as the north–south dividing line; however, Baltimore Street is north–south dividing line for the U.S. Postal Service.[119]

Central Baltimore

Central Baltimore, originally called the Middle District,[120] stretches north of the Inner Harbor up to the edge of Druid Hill Park. Downtown Baltimore has mainly served as a commercial district with limited residential opportunities; however, between 2000 and 2010, the downtown population grew 130 percent as old commercial properties have been replaced by residential property.[121] Still the city's main commercial area and business district, it includes Baltimore's sports complexes: Oriole Park at Camden Yards, M&T Bank Stadium, and the Royal Farms Arena; and the shops and attractions in the Inner Harbor: Harborplace, the Baltimore Convention Center, the National Aquarium, Maryland Science Center, Pier Six Pavilion, and Power Plant Live.[119]

The University of Maryland, Baltimore, the University of Maryland Medical Center, and Lexington Market are also in the central district, as well as the Hippodrome and many nightclubs, bars, restaurants, shopping centers and various other attractions.[119][120] The northern portion of Central Baltimore, between downtown and the Druid Hill Park, is home to many of the city's cultural opportunities. Maryland Institute College of Art, the Peabody Institute (music conservatory), George Peabody Library, Enoch Pratt Free Library – Central Library, the Lyric Opera House, the Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall, the Walters Art Museum, the Maryland Center for History and Culture and its Enoch Pratt Mansion, and several galleries are located in this region.[122]

North Baltimore

Several historic and notable neighborhoods are in this district: Govans (1755), Roland Park (1891), Guilford (1913), Homeland (1924), Hampden, Woodberry, Old Goucher (the original campus of Goucher College), and Jones Falls. Along the York Road corridor going north are the large neighborhoods of Charles Village, Waverly, and Mount Washington. The Station North Arts and Entertainment District is also located in North Baltimore.[123]

South Baltimore

South Baltimore, a mixed industrial and residential area, consists of the "Old South Baltimore" peninsula below the Inner Harbor and east of the old B&O Railroad's Camden line tracks and Russell Street downtown. It is a culturally, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse waterfront area with neighborhoods such as Locust Point and Riverside around a large park of the same name.[124] Just south of the Inner Harbor, the historic Federal Hill neighborhood, is home to many working professionals, pubs and restaurants. At the end of the peninsula is historic Fort McHenry, a National Park since the end of World War I, when the old U.S. Army Hospital surrounding the 1798 star-shaped battlements was torn down.[125]

Across the Hanover Street Bridge are residential areas such as Cherry Hill.[126]

Northeast Baltimore

Northeast is primarily a residential neighborhood, home to Morgan State University, bounded by the city line of 1919 on its northern and eastern boundaries, Sinclair Lane, Erdman Avenue, and Pulaski Highway to the south and The Alameda on to the west. Also in this wedge of the city on 33rd Street is Baltimore City College high school, third oldest active public secondary school in the United States, founded downtown in 1839.[127] Across Loch Raven Boulevard is the former site of the old Memorial Stadium home of the Baltimore Colts, Baltimore Orioles, and Baltimore Ravens, now replaced by a YMCA athletic and housing complex.[128][129] Lake Montebello is in Northeast Baltimore.[120]

East Baltimore

Located below Sinclair Lane and Erdman Avenue, above Orleans Street, East Baltimore is mainly made up of residential neighborhoods. This section of East Baltimore is home to Johns Hopkins Hospital, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and Johns Hopkins Children's Center on Broadway. Notable neighborhoods include: Armistead Gardens, Broadway East, Barclay, Ellwood Park, Greenmount, and McElderry Park.[120]

This area was the on-site film location for Homicide: Life on the Street, The Corner and The Wire.[130]

Southeast Baltimore

Southeast Baltimore, located below Fayette Street, bordering the Inner Harbor and the Northwest Branch of the Patapsco River to the west, the city line of 1919 on its eastern boundaries and the Patapsco River to the south, is a mixed industrial and residential area. Patterson Park, the "Best Backyard in Baltimore",[131] as well as the Highlandtown Arts District, and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center are located in Southeast Baltimore. The Shops at Canton Crossing opened in 2013.[132] The Canton neighborhood, is located along Baltimore's prime waterfront. Other historic neighborhoods include: Fells Point, Patterson Park, Butchers Hill, Highlandtown, Greektown, Harbor East, Little Italy, and Upper Fell's Point.[120]

Northwest Baltimore

Northwestern is bounded by the county line to the north and west, Gwynns Falls Parkway on the south and Pimlico Road on the east, is home to Pimlico Race Course, Sinai Hospital, and the headquarters of the NAACP. Its neighborhoods are mostly residential and are dissected by Northern Parkway. The area has been the center of Baltimore's Jewish community since after World War II. Notable neighborhoods include: Pimlico, Mount Washington, and Cheswolde, and Park Heights.[133]

West Baltimore

West Baltimore is west of downtown and the Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and is bounded by Gwynns Falls Parkway, Fremont Avenue, and West Baltimore Street. The Old West Baltimore Historic District includes the neighborhoods of Harlem Park, Sandtown-Winchester, Druid Heights, Madison Park, and Upton.[134][135] Originally a predominantly German neighborhood, by the last half of the 19th century, Old West Baltimore was home to a substantial section of the city's Black population.[134]

It became the largest neighborhood for the city's Black community and its cultural, political, and economic center.[134] Coppin State University, Mondawmin Mall, and Edmondson Village are located in this district. The area's crime problems have provided subject material for television series, such as The Wire.[136]

Southwest Baltimore

Southwest Baltimore is bound by the Baltimore County line to the west, West Baltimore Street to the north, and Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and Russell Street/Baltimore-Washington Parkway (Maryland Route 295) to the east. Notable neighborhoods in Southwest Baltimore include: Pigtown, Carrollton Ridge, Ridgely's Delight, Leakin Park, Violetville, Lakeland, and Morrell Park.[120]

St. Agnes Hospital on Wilkens and Caton[120] avenues is located in this district with the neighboring Cardinal Gibbons High School, which is the former site of Babe Ruth's alma mater, St. Mary's Industrial School. Through this segment of Baltimore ran the beginnings of the historic National Road, which was constructed beginning in 1806 along Old Frederick Road and continuing into the county on Frederick Road into Ellicott City, Maryland. Other sides in this district are: Carroll Park, one of the city's largest parks, the colonial Mount Clare Mansion, and Washington Boulevard, which dates to pre-Revolutionary War days as the prime route out of the city to Alexandria, Virginia, and Georgetown on the Potomac River.[citation needed]

Adjacent communities

Baltimore is bordered by the following communities, all unincorporated census-designated places.

المناخ

| متوسطات الطقس لبلتيمور | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| شهر | يناير | فبراير | مارس | أبريل | مايو | يونيو | يوليو | أغسطس | سبتمبر | اكتوبر | نوفمبر | ديسمبر | السنة |

| العظمى القياسية °F (°C) | 79 (26) | 84 (29) | 97 (36) | 98 (37) | 100 (38) | 105 (41) | 107 (42) | 105 (41) | 102 (39) | 97 (36) | 87 (31) | 85 (29) | 107 (42) |

| متوسط العظمى °ف (°م) | 44 (7) | 47 (8) | 57 (14) | 68 (20) | 77 (25) | 86 (30) | 91 (33) | 88 (31) | 81 (27) | 70 (21) | 59 (15) | 49 (9) | 68 (20) |

| متوسط الصغرى °ف (°م) | 29 (-2) | 31 (-1) | 39 (4) | 48 (9) | 58 (14) | 68 (20) | 73 (23) | 71 (22) | 64 (18) | 52 (11) | 42 (6) | 33 (1) | 51 (11) |

| الصغرى القياسية °ف (°C) | -4 (-20) | -7 (-22) | 11 (-12) | 15 (-9) | 32 (0) | 46 (8) | 54 (12) | 52 (11) | 40 (4) | 30 (-1) | 12 (-11) | -2 (-19) | −7 (−22) |

| هطول الأمطار بوصة (mm) | 3.5 (88.9) | 3.1 (78.7) | 4.1 (104.1) | 3.1 (78.7) | 4.2 (106.7) | 3.3 (83.8) | 4.0 (101.6) | 4.1 (104.1) | 4.1 (104.1) | 3.2 (81.3) | 3.5 (88.9) | 3.7 (94) | 43٫9 (1٬115٫1) |

| المصدر: The Weather Channel[137] September 2008 | |||||||||||||

منظر المدينة

العمارة

لدى بلتيمور أمثلة من كل فترة معمارية على مر قرنين من الزمان، وأعمال من العديد من مشاهير المعماريين، مثل بنجامن لاتروب، جون رسل پوپ، ميس ڤان در روه و I.M. Pei.

أعلى المباني

| الترتيب | المبنى | الارتفاع | الطوابق | بني | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Legg Mason Building | 529 أقدام (161 m) | 40 | 1973 | [138] |

| 2 | Bank of America Building | 509 أقدام (155 m) | 37 | 1924 | [139] |

| 3 | William Donald Schaefer Building | 493 أقدام (150 m) | 37 | 1992 | [140] |

| 4 | Commerce Place | 454 أقدام (138 m) | 31 | 1992 | [141] |

| 5 | 100 East Pratt Street | 418 أقدام (127 m) | 28 | 1992 | [142] |

| 6 | Baltimore World Trade Center | 405 أقدام (123 m) | 32 | 1977 | [143] |

| 7 | Tremont Plaza Hotel | 395 أقدام (120 m) | 37 | 1967 | [144] |

| 8 | Charles Towers South Apartments | 385 أقدام (117 m) | 30 | 1969 | [145] |

| 9 | Blaustein Building | 360 أقدام (110 m) | 30 | 1962 | [146] |

| 10 | 250 West Pratt Street | 360 أقدام (110 m) | 24 | 1986 | [147] |

الأحياء السكنية

الثقافة

Historically a working-class port town, Baltimore has sometimes been dubbed a "city of neighborhoods," with over 300 identified districts[148]

ميناء بلتيمور

الميناء الداخلي

مقالة مفصلة: الميناء الداخلي، بلتيمور

مقالة مفصلة: الميناء الداخلي، بلتيمور

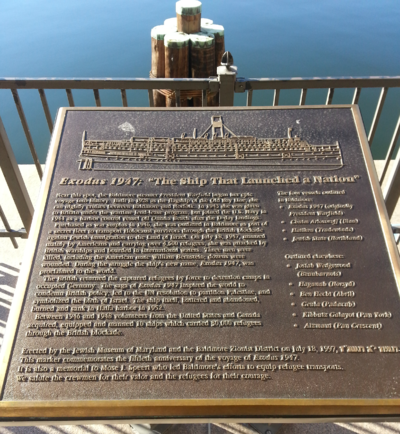

إكسودس 1947: "السفينة التي أطلقت أمة"

وهي الباخرة التابعة للبحرية الأمريكية، التي حملت سراً في عام 1947، 4,500 مهاجر يهودي من فرنسا إلى فلسطين، لتعيدهم بريطانيا إلى ألمانيا المحتلة. ويلقى الحادث، حتى اليوم، اهتماماً بالغاً في تاريخ قيام دولة إسرائيل.

المدن الشقيقة

لدى بلتيمور 11 مدينة شقيقة, as designated by Sister Cities International, Inc. (SCI):

انظر أيضاً

- عربير

- شرطة بالتيمور

- لهجة بالتيمور

- شركة بالتيمور باكت البخارية ("خط الخليج القديم")

- مقابر في بالتيمور

- مقاطعة ديكفيل التاريخية

- إليزا ريدجلي

- مكتبة إنوتش برات الحرة

- فورمستون

- قائمة منتزهات منطقة بالتيمور-واشنطن الكبرى

- قائمة أشخاص من بالتيمور

- مايكل فيلبس

- موسيقى بالتيمور

- ناشونال بوهميان

- بلوج أوجليز

- Royal Blue (B&O train)

- Screen painting

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت Donovan, Doug (May 20, 2006). "Baltimore's New Bait: The City is About to Unveil a New Slogan, 'Get In On It,' Meant to Intrigue Visitors". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved November 28, 2008 – via RedOrbit.

- ^ Kane, Gregory (June 15, 2009). "Dispatch from Bodymore, Murderland". The Washington Examiner.

- ^ Cutler, Josh S. (February 18, 2019). Mobtown Massacre: Alexander Hanson and the Baltimore Newspaper War of 1812. ISBN 978-1-4396-6620-3.

- ^ Gettleman, Jeffrey (September 2, 2003). "In Baltimore, Slogan Collides with Reality". The New York Times.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ أ ب "Highest and Lowest Elevations in Maryland's Counties". Maryland Geological Survey. Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Baltimore City. Archived from the original on October 5, 2007. Retrieved November 14, 2007.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةpopchange21 - ^ "List of 2020 Census Urban Areas". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ "2020 Population and Housing State Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ "ZIP Code Lookup". USPS. Archived from the original on November 22, 2010. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ^ Britto, Brittany. "How Baltimore talks". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ^ "QuickFacts: Baltimore city (County)". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ أ ب "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals: 2020–2021" (CSV). 2021 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. May 2022. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ Youssi, Adam (2006). "The Susquehannocks' Prosperity & Early European Contact". Historical Society of Baltimore County. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ "About Baltimore". Baltimore.org. Archived from the original on July 25, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ "Baltimore Heritage Area". Maryland Historical Trust. February 11, 2011. Archived from the original on February 2, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2011.

- ^ "Major Employers | Baltimore Development Corporation". Baltimoredevelopment.com. Archived from the original on July 25, 2010. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ Gibbons, Mike (October 21, 2011). "Monumental City Welcomes Number Five". Babe Ruth Birthplace Foundation. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ أ ب Sherman, Natalie (March 14, 2015). "Historic districts proliferate as city considers changes". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on July 11, 2017.

- ^ "Building on Baltimore's History: The Partnership for Building Reuse" (PDF). Preservation Green Lab, National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Urban Land Institute Baltimore. November 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ Baltimore City, Maryland: Historical Chronology, Maryland State Archives, February 29, 2016, http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdmanual/36loc/bcity/chron/html/bcitychron17.html, retrieved on April 11, 2016; Calvert Family Tree, University Libraries, University of Maryland, http://www.lib.umd.edu/binaries/content/assets/public/special/projects/riversdale/calvertfamilytree.pdf, retrieved on April 11, 2016

- ^ Maryland History Timeline, Maryland Office of Tourism, http://www.visitmaryland.org/info/maryland-history-timeline, retrieved on April 11, 2016

- ^ أ ب ت Egan, Casey (November 23, 2015), The surprising Irish origins of Baltimore, Maryland, http://www.irishcentral.com/roots/history/The-surprising-Irish-origins-of-Baltimore-Maryland.html, retrieved on April 11, 2016

- ^ Brugger, Robert J. (1988). Maryland: A Middle Temperament, 1634–1980. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8018-3399-1.

- ^ أ ب Akerson, Louise A. (1988). American Indians in the Baltimore area. Baltimore, Maryland: Baltimore Center for Urban Archaeology (Md.). p. 15. OCLC 18473413.

- ^ Shen, Fern (December 4, 2021). "Discovered in Baltimore park: Native American artifacts 5,000-9,000 years old". Baltimore Brew. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ Potter, Stephen R. (1993). Commoners, Tribute, and Chiefs: The Development of Algonquian Culture in the Potomac Valley. Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-8139-1422-0. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- ^ Adam Youssi (2006). "The Susquehannocks' Prosperity & Early European Contact". Historical Society of Baltimore County. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ Flick, Alex J.; et al. (2012). "A Place Now Known Unto Them: The Search for Zekiah Fort" (PDF). Site Report: 11. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ Murphree, Daniel Scott (2012). Native America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 489, 494. ISBN 978-0-313-38126-3. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ As depicted on a map of the Piscataway lands in Kenneth Bryson, Images of America: Accokeek (Arcadia Publishing, 2013) pp. 10–11, derived from Alice and Henry Ferguson, The Piscataway Indians of Southern Maryland (Alice Ferguson Foundation, 1960) pp. 8 (map) and 11: "By the beginning of Maryland settlement, pressure from the Susquehannocks had reduced...the Piscataway 'empire'...to a belt bordering the Potomac south of the falls and extending up the principal tributaries. Roughly, the 'empire' covered the southern half of present Prince Georges County and all, or nearly all, of Charles County."

- ^ "St. Clements Island State Park". Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ أ ب Brooks & Rockel (1979), pp. 1–3.

- ^ أ ب Tom (March 10, 2014). "Baltimore History Traced in Street Names". Ghosts of Baltimore. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Bacon, Thomas (1765). Laws of Maryland at Large, with Proper Indexes. Vol. 75. Annapolis: Jonas Green. p. 61.

- ^ Brooks & Rockel (1979), pp. 17–18.

- ^ Charlotte and "Doc" Cronin (September 19, 2014). "Remembering Old Baltimore when it was near Aberdeen". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ "Carroll Museums: Making History Yours". carrollmuseums.org. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved August 4, 2015.

- ^ Brooks & Rockel (1979), pp. 29–30.

- ^ Thomas, 1874, p. 323

- ^ Wroth, 1938, p. 41

- ^ Wroth, 1922, p. 114

- ^ Kent Mountford (July 1, 2003). "History behind sugar trade, Chesapeake not always sweet". Bay Journal. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ Sharan, Mallika. "History". Baltimore Public Markets Corporation. Archived from the original on August 12, 2015. Retrieved August 4, 2015.

- ^ Mallika Sharan. "World Famous Lexington Market". lexingtonmarket.com. Retrieved August 4, 2015.

- ^ "The secret history of city slave trade". June 20, 1999.

- ^ Thielking, Megan (November 10, 2015). "25 Things You Should Know About Baltimore". Mental Floss. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

In 1774, the first post office in the United States was inaugurated in the city.

- ^ "Baltimore: A City of Firsts". Visit Baltimore. Archived from the original on February 3, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Baltimore City, Maryland Historical Chronology". Maryland State Archives. December 7, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ Hezekiah Niles (1876). Principles and Acts of the Revolution in America. New York: A. S. Barnes & Co. pp. 257–258.

baltimore non-importation agreement.

- ^ "Henry Fite's House, Baltimore". U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian. Archived from the original on March 26, 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ Laura Rich. Maryland History in Prints 1743–1900. p. 45.

- ^ "The Great Strike". Catskill Archive. Timothy J. Mallery. Archived from the original on September 29, 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ^ "Baltimore, Maryland—Government". Maryland Manual On-Line: A Guide to Maryland Government. Maryland State Archives. October 23, 2008. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2008.

- ^ "Baltimore, October 17". Salem Gazette. Salem, Massachusetts. October 23, 1827. p. 2. Retrieved October 27, 2008 – via NewsBank.

- ^ William Harvey Hunter, "Baltimore Architecture in History"; in Dorsey & Dilts (1997), p. 7. "Both begun in 1815, the Battle Monument and the Washington Monument gave Baltimore its most famous sobriquet. In 1827, when bremoth of them were nearly finished, President John Quincy Adams at a big public dinner in Baltimore gave as his toast, 'Baltimore, the monumental city.' It was more than an idle comment: no other large city in America had even one substantial monument to show."

- ^ Townsend (2000), pp. 62–68.

- ^ "The Baltimore Bank Riot". University of Illinois Press. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ "Maryland Historical Chronology: 1800–1899". Maryland State Archives. August 24, 2021. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ أ ب "The Baltimore Plot". National Park Service. Retrieved 13 July 2025.

- ^ Clayton, Ralph (July 12, 2000). "A bitter Inner Harbor legacy: the slave trade". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ McPherson, James M. (December 11, 2003). Battle Cry of Freedom. US: Oxford University Press. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-19-516895-2.

- ^ Scharf (1879), Vol. 3, pp. 728–742.

- ^ Gavit, John Palmer (1897). Bibliography of College, Social and University Settlements (in الإنجليزية) (Public domain ed.). Co-operative Press. p. 24. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

هذه المقالة تتضمن نصاً من منشور يخضع حالياً للملكية العامة:

هذه المقالة تتضمن نصاً من منشور يخضع حالياً للملكية العامة:

- ^ Woods, Robert Archey; Kennedy, Albert Joseph (1911). Handbook of Settlements (in الإنجليزية) (Public domain ed.). Charities Publication Committee. pp. 100–01. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

هذه المقالة تتضمن نصاً من منشور يخضع حالياً للملكية العامة:

هذه المقالة تتضمن نصاً من منشور يخضع حالياً للملكية العامة:

- ^ "A Howling Inferno: The Great Baltimore Fire" (Press release). Johns Hopkins University. January 12, 2004. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- ^ Petersen, Pete (2009). "Legacy of the Fire". The Fire Museum of Maryland. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ^ Power, Garrett (1983). "Apartheid Baltimore Style: the Residential Segregation Ordinances of 1910–1913". Maryland Law Review. 42 (2): 299–300.

- ^ Power (1983), p. 289.

- ^ George P. Bagby, ed. (1918). The annotated code of the public civil laws of Maryland, Volume 4. King Bros., Printers and Publishers. p. 769.

- ^ Duffy, James (December 2007). "Baltimore seals its borders". Baltimore. pp. 124–27.

- ^ Orser (1994), pp. 21–30.

- ^ Alabaster cities: urban U.S. since 1950. John R. Short (2006). Syracuse University Press. p.142. ISBN 0-8156-3105-7

- ^ Orser (1994), pp. 84–94.

- ^ "Baltimore '68 Events Timeline". Baltimore 68: riots and Rebirth. University of Baltimore Archives. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ^ Police Chief Donald Pomerleau said, "We're in a semi-riot mode, similar to the 1968 riots." See: "Cops storm jail rebels; Baltimore in semi-riot state". Chicago Tribune. UPI. July 14, 1974. ProQuest 171096090.

- ^ Sandler, Gilbert (July 18, 1995). "How the city's nickname came to be". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ Sandler, Gil (August 18, 1998). "Where did city get its charming nickname? Baltimore Glimpses". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ Fuller, Nicole (February 28, 2007). "Moveable Feast, which gives food to HIV/AIDS, terminally ill patients, might turn away clients". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on April 17, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ Hill, Retha (June 9, 1990). "Meals a Godsend To AIDS Patients;Md. Program Helps Ease Burden for Homebound". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 16, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ "History of Moveable Feast". About Us. Moveable Feast. 2015. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ "Who We Are". Maryland Stadium Authority. Archived from the original on October 18, 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ^ Mary Rose Madden, "On The Watch, Part 6: Baltimore's Homicide Numbers Spike As Closure Rate Drops"; WYPR February 18, 2016.

- ^ Jess Bidgood, "The Numbers Behind Baltimore's Record Year in Homicides", The New York Times, January 15, 2016.

- ^ Smith, Jocelyn R. (July 2015). "Unequal Burdens of Loss: Examining the Frequency and Timing of Homicide Deaths Experienced by Young Black Men Across the Life Course". American Journal of Public Health (in الإنجليزية). 105 (S3): S483–S490. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302535. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 4455517. PMID 25905836.

- ^ Sanburn, Josh (June 2, 2015). "What's Behind Baltimore's Record-Setting Rise in Homicides". Time. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ Rousuck, J. Wynn; Gunts, Edward (January 25, 2005). "Hippodrome's first hurrahs". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ "UAE royal family honoured at opening of new Johns Hopkins Hospital". Middle East Health. May 2012. Archived from the original on February 4, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ Gantz, Sarah (April 13, 2012). "Photos: Johns Hopkins dedicates $1.1 billion patient towers". Baltimore Business Journal. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ "Sagamore: A major opportunity that requires scrutiny equal in scale". The Baltimore Sun. March 24, 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ Martin, Olivia (September 22, 2016). "Baltimore city council approves $660 million for "Build Port Covington"". Archpaper.com. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ Mirabella, Lorraine. "Goldman Sachs invests $233 million in Port Covington". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- ^ Alonso, Melissa; Wolfe, Elizabeth (March 26, 2024). "Rescuers are searching for at least 7 people in the water after Baltimore bridge collapse, official says". CNN. Archived from the original on March 26, 2024. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ Skene, Lea (March 27, 2024). "Police had about 90 seconds to stop traffic before Baltimore bridge fell. 6 workers are feared dead". Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 29, 2024. Retrieved March 27, 2024.

- ^ Ng, Greg (March 26, 2024). "'Key Bridge is gone': Ship strike destroys bridge, state of emergency declared". WBAL. Archived from the original on March 26, 2024. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ Starkey, Josh (May 7, 2024). "Sixth victim's body recovered at Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse site". WBAL (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ Witte, Brian (May 2, 2024). "Maryland officials release timeline, cost estimate, for rebuilding bridge". Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 2, 2024. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ "(no title provided)". 2010 Census Gazetteer Files. United States Census Bureau. Counties > Maryland. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ Dorsey & Dilts (1997), pp. 182–183. "Once there were three such towers in Baltimore; now there are only a few left in the world."

- ^ Evitts, Elizabeth (April 2003). "Window to the Future" (PDF). Baltimore. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 11, 2011. Retrieved May 6, 2009 – via Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church.

- ^ Bishop, Tricia (April 7, 2003). "Illuminated by a jewel". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ "About | Top of the World Observation Level - Baltimore". viewbaltimore.org. Retrieved 2024-10-06.

- ^ Paul K. Williams (September 23, 2009). "The Story of Formstone". Welcome to Baltimore, Hon!. Archived from the original on November 30, 2010. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ^ Mary Ellen Hayward and Charles Belfoure (1999). The Baltimore Rowhouse. Princeton Architectural Press. p. back cover. ISBN 978-1-56898-283-0. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ^ Hayward and Belfoure, pp 17–18, 22.

- ^ "University of Baltimore Law School Wins ENR National "Best of the Best" Award for Design and Construction". Mueller Associates. January 2, 2014. Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved May 13, 2017.

- ^ "Everyman Theatre Honored with 'Baltimore Heritage Historic Preservation Award'". Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ Hopkins, Jamie Smith (October 31, 2011). "Transamerica workers begin move to downtown skyscraper". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ^ "Legg Mason Building". Emporis Corporation. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Bank of America Building". Emporis Corporation. Archived from the original on February 14, 2007. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Gantz, Sarah. "Questar tops off 414 Light St. tower on Baltimore Inner Harbor". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ "William Donald Schaefer Tower". Emporis Corporation. Archived from the original on February 17, 2007. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Commerce Place". Emporis Corporation. Archived from the original on February 13, 2007. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Baltimore Marriott Waterfront Hotel". Skyscraper Center. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "100 East Pratt Street". Emporis Corporation. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Trade Center". Emporis Corporation. Archived from the original on February 21, 2007. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Tremont Plaza Hotel". Emporis Corporation. Archived from the original on February 17, 2007. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Charles Towers South Apartments". Emporis Corporation. Archived from the original on February 19, 2007. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ أ ب ت Tilghman, Mary K. (2008). Insiders' Guide to Baltimore. Insiders' Guide Series. Elizabeth A. Evitts (5th ed.). Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7627-4553-1. OCLC 144227820.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Central District, http://baltimorecitypolicedept.org/citypolice/baltimore-police-districts/central-district.html, retrieved on April 12, 2016

- ^ Bernstein, Rachel (May 17, 2011). "Families increasing in downtown Baltimore". The Daily Record. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- ^ "Baltimore". Visit Baltimore. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ Northern District Area Guide, Baltimore Police Department, Neighborhood Resources, https://www.baltimorepolice.org/northern-district, retrieved on April 12, 2016

- ^ Scott Sheads. "Locust Point – Celebrating 300 Years of a Historic Community". Locust Point Civic Association. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Discover Federal Hill". Historic Federal Hill. Archived from the original on March 7, 2011. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ "Cherry Hill Master Plan (II. History of Cherry Hill)" (PDF). Cherry Hill Community Web Site. Baltimore City Department of Planning. July 10, 2008. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 12, 2011. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ Anft, Michael. "Contrasting studies". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on September 9, 2005. Retrieved July 29, 2007.

- ^ "Profile of General Demographic Characteristics (2000): Hillen" (PDF). Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance. Baltimore City Department of Planning. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 12, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ "Profile of General Demographic Characteristics (2000): Stonewood-Pentwood-Winston" (PDF). Baltimore Neighborhoods Indicators Alliance. Baltimore City Department of Planning. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 12, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ Gadi Dechter (May 24, 2006). "A Guided Tour of "The Wire's" East Baltimore". Baltimore City Paper. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ Collins, Dan (December 18, 2008), "Patterson Park: Best backyard in Baltimore", Washington Examiner, http://www.washingtonexaminer.com/patterson-park-best-backyard-in-baltimore/article/43971, retrieved on March 30, 2016

- ^ "The Shops at Canton Crossing is Officially Open for Business". CBS Baltimore. October 8, 2013. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ "Park Heights". Live in Baltimore. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت HRG Consultants; AB Associates (Sep 2001), Baltimore City Heritage Area: Management Action Plan, https://www.nps.gov/balt/learn/management/upload/Section-I-Background.pdf, retrieved on May 15, 2016

- ^ Registration form: Old West Baltimore Historic District, National Register of Historic Places, November 9, 2004, https://mht.maryland.gov/secure/medusa/PDF/NR_PDFs/NR-1390.pdf, retrieved on May 15, 2016

- ^ Capital News Service (May 3, 2016), "Part 3 Unhealthy Baltimore: Distrust in the hospital room", The Baltimore Sun, http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/freddie-gray/bs-md-ci-unrest-anniversary-20160427-story.html, retrieved on May 15, 2016

- ^ "Monthly Averages for Baltimore, MD". The Weather Channel. 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ Emporis - Legg Mason Building. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ Emporis - Bank of America Building. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ Emporis - William Donald Schaefer Tower. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ Emporis - Commerce Place. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ Emporis - 100 East Pratt Street. Retrieved 1 November 2006.

- ^ Emporis - World Trade Center. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ Emporis - Tremont Plaza Hotel. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ Emporis - Charles Towers South Apartments. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ Emporis - Blaustein Building. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ Emporis - 250 West Pratt Street. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ "Baltimore Neighborhoods". City of Baltimore, Maryland. Retrieved 2007-06-14.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

وصلات خارجية

- City of Baltimore Website

- Baltimore Area Convention and Visitors Association

- Baltimore History Time Line

- Visit My Baltimore

- The Baltimore Collective — MediaWiki cultural archive project for Baltimore, Maryland US

- Baltimore Development Corporation

- Baltimore Walking Tours

- Fells Point Ghost Tours- Baltimore Ghost Tour

- How to Renovate a Baltimore Rowhouse

- Buildings of Baltimore

- The Phoenix Shot Tower in Baltimore's Inner Harbor

- Baltimore Weather - Live weather, air quality, and archived weather from the UMBC weather station.

- Baltimore, Maryland, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- NOAA Charts(linked 4/2007)

- Chapter 15 Baltimore to Head of Chesapeake Bay, Coast Pilot 3, 40th Edition, 2007, Office of Coastal Survey, NOAA.

| سبقه فيلادلفيا |

عاصمة الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 1776-1777 |

تبعه فيلادلفيا |

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- Source attribution

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2016

- مدن تأسست في 1729

- بتليمور، مريلاند

- مدن في مريلاند

- عواصم سابقة للولايات المتحدة

- مدن مستقلة في الولايات المتحدة

- مدن موانئ في الولايات المتحدة

- United States communities with African American majority populations

- خليج تشيزاپيك

- مدن الولايات المتحدة

- جاليات اوكرانية في الولايات المتحدة

- صفحات مع الخرائط