إل پاسو، تكساس

إل پاسو

El Paso | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| الكنية: | |

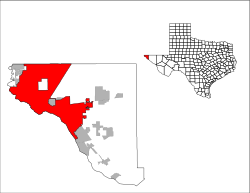

الموقع في مقاطعة إل پاسو وولاية تكساس | |

الموقع في مقاطعة إل پاسو وولاية تكساس | |

| الإحداثيات: 31°45′33″N 106°29′19″W / 31.75917°N 106.48861°W | |

| البلد | الولايات المتحدة |

| الولاية | تكساس |

| المقاطعة | إل پاسو |

| أول استيطان | 1680 |

| استوطنت باسم فرانكلن | 1849 |

| أعيد تسميتها إل پاسو | 1852 |

| تأسيس البلدة | 1859 |

| دُمجت | 1873 |

| الحكومة | |

| • النوع | المجلس-رئيس المدينة |

| • مجلس المدينة |

|

| • رئيس المدينة | كلااري وستين (بالإنابة) |

| المساحة | |

| • مدينة | 259٫25 ميل² (671٫46 كم²) |

| • البر | 258٫43 ميل² (669٫33 كم²) |

| • الماء | 0٫82 ميل² (2٫13 كم²) |

| المنسوب | 3٬740 ft (1٬140 m) |

| التعداد | |

| • مدينة | 678٬815 |

| • الترتيب | رقم 22 في الولايات المتحدة رقم 6 في تكساس |

| • الكثافة | 2٬626٫69/sq mi (1٬014٫17/km2) |

| • Urban | 854٬584 (الولايات المتحدة: رقم 53) |

| • الكثافة الحضرية | 3٬339٫7/sq mi (1٬289٫5/km2) |

| • العمرانية | 868٬859 (الولايات المتحدة: رقم 67) |

| صفة المواطن | El Pasoan |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC−07:00 (MST) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC−06:00 (MDT) |

| الرمز البريدي |

|

| رمز المنطقة | 915 |

| رمز FIPS | 48-24000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1380946[6] |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www |

إل پاسو (إنگليزية: El Paso)، مدينة أمريكية تقع في ولاية تكساس. وهي حاضرة مقاطعة إل باسو، وأكبر مدن منطقة غرب تكساس، وسادس أكبر مدن الولاية. حسب تقديرات عام 2005 عدد سكان المدينة 598590 نسمة. تقع المدينة على الحدود الأمريكية-المكسيكية بالقرب من مدينة خواريز المكسيكية. توجد في المدينة جامعة تكساس في إل باسو التي تأسست في عام 1914 كمدرسة. مساحة المدينة 648.9 كم2. اسم المدينة أخذ من عبارة "El Paso de Norte" (الطريق أو الممر نحو الشمال) والتي تشير إلى مدينة خواريز المكسيكية حالياً.

تستخدم بوابةً رئيسية للسفر بين البلدين. كما أنها مركزٌُ مُهِمٌّ للتصنيع والتوزيع في الجنوب الغربي. ويبلغ عدد سكانها 563,662 نسمة.

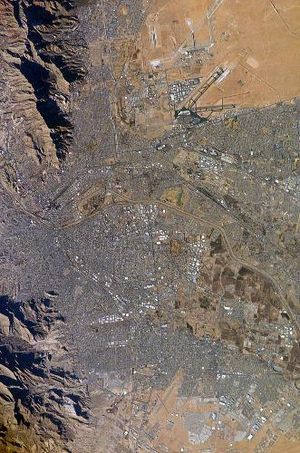

تمتد مدينة إل باسو على الحافة الشمالية لنهر ريو گراند، في الزاوية الغربية البعيدة لولاية تكساس، على ممر بين جبال سييرا مادرى في المكسيك إلى الجنوب وجبال فرانكلن إلى الشمال حيث يمتد جزء من المدينة فوقها.

التاريخ

السنوات المبكرة

The El Paso region has had human settlement for thousands of years, as evidenced by Folsom points from hunter-gatherers found at Hueco Tanks. This suggests 10,000 to 12,000 years of human habitation.[7] The earliest known cultures in the region were maize farmers. When the Spanish arrived, the Manso, Suma, and Jumano tribes populated the area. These were subsequently incorporated into the mestizo culture, along with immigrants from central Mexico, captives from Comanchería, and genízaros of various ethnic groups. The Mescalero Apache were also present.[8]

The Chamuscado and Rodríguez Expedition trekked through present-day El Paso and forded the Rio Grande where they visited the land that is present-day New Mexico in 1581–1582. The expedition was led by Francisco Sánchez, called "El Chamuscado", and Fray Agustín Rodríguez, the first Spaniards known to have walked along the Rio Grande and visited the Pueblo Indians since Francisco Vásquez de Coronado 40 years earlier. Spanish explorer Don Juan de Oñate was born in 1550 in Zacatecas, Zacatecas, Mexico, and was the first New Spain (Mexico) explorer known to have rested and stayed 10 days by the Rio Grande near El Paso, in 1598,[9] celebrating a Thanksgiving Mass there on April 30, 1598. Four survivors of the Narváez expedition, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, Alonso del Castillo Maldonado, Andrés Dorantes de Carranza, and an enslaved native of Morocco, Estevanico, are thought to have crossed the Rio Grande into present-day Mexico about 75 miles south of El Paso in 1535.[10] El Paso del Norte (present-day Ciudad Juárez) was founded on the south bank of the Río Bravo del Norte (Rio Grande), in 1659 by Fray Garcia de San Francisco. In 1680, the small village of El Paso became the temporary base for Spanish governance of the territory of New Mexico as a result of the Pueblo Revolt, until 1692, when Santa Fe was reconquered and once again became the capital.[11]

The Texas Revolution (1836) was generally not felt in the region, as the American population was small, not more than 10% of the population. However, the region was claimed by Texas as part of the treaty signed with Mexico and numerous attempts were made by Texas to bolster these claims, but the villages that consisted of what is now El Paso and the surrounding area remained essentially a self-governed community with both representatives of the Mexican and Texan governments negotiating for control until Texas, having become a U.S. state in 1845, irrevocably took control in 1846.[12] During this interregnum, 1836–1848, Americans nonetheless continued to settle the region. As early as the mid-1840s, alongside long extant Hispanic settlements such as the Rancho de Juan María Ponce de León, Anglo-American settlers such as Simeon Hart and Hugh Stephenson had established thriving communities of American settlers owing allegiance to Texas.[12] Stephenson, who had married into the local Hispanic aristocracy, established the Rancho de San José de la Concordia, which became the nucleus of Anglo-American and Hispanic settlement within the limits of modern-day El Paso, in 1844: the Republic of Texas, which claimed the area, wanted a chunk of the Santa Fe trade. During the Mexican–American War, the Battle of El Bracito was fought nearby on Christmas Day, 1846. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo effectively made the settlements on the north bank of the river part of the US, separate from Old El Paso del Norte on the Mexican side.[12] The present New Mexico–Texas boundary placing El Paso on the Texas side was drawn in the Compromise of 1850.[13][14]

El Paso remained the largest settlement in New Mexico as part of the Republic of Mexico until its cession to the U.S. in 1848, when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo specified the border was to run north of El Paso De Norte around the Ciudad Juárez Cathedral which became part of the state of Chihuahua.[15]

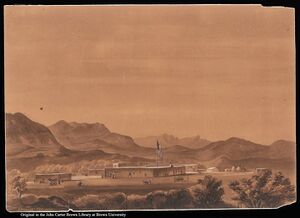

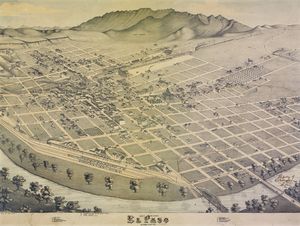

El Paso County was established in March 1850, with San Elizario as the first county seat.[16] The United States Senate fixed a boundary between Texas and New Mexico at the 32nd parallel, thus largely ignoring history and topography. A military post called the "Post opposite El Paso" (meaning opposite El Paso del Norte, across the Rio Grande) was established in 1849 on Coons' Rancho beside the settlement of Franklin, which became the nucleus of the future El Paso, Texas; after the army left in 1851, the rancho went into default and was repossessed; in 1852, a post office was established on the rancho bearing the name El Paso as an example of cross-border town naming until El Paso del Norte was renamed Juarez in 1888. After changing hands twice more, the El Paso company was set up in 1859 and bought the property, hiring Anson Mills to survey and lay out the town, thus forming the current street plan of downtown El Paso.[17]

In Beyond the Mississippi (1867), Albert D. Richardson, traveling to California via coach, described El Paso as he found it in late 1859:

The Texan town of El Paso had four hundred inhabitants, chiefly Mexicans. Its businessmen were Americans, but Spanish was the prevailing language. All the features were Mexican: low, flat adobe buildings, shading cottonwoods under which dusky, smoking women and swarthy children sold fruit, vegetables, and bread; habitual gambling universal, from the boys' game of pitching quartillas (three-cent coins) to the great saloons where huge piles of silver dollars were staked at monte. In this little village, a hundred thousand dollars often changed hands in a single night through the potent agencies of Monte and poker. There were only two or three American ladies, and most of the whites kept Mexican mistresses. All goods were brought on wagons from the Gulf of Mexico and sold at an advance of three or four hundred percent on Eastern prices.[18]

From hills overlooking the town, the eye takes in a charming picture—a far-stretching valley, enriched with orchards, vineyards, and cornfields, through which the river traces a shining pathway. Across it appears the flat roofs and cathedral towers of the old Mexican El Paso; still further, dim misty mountains melt into the blue sky.[18]

During the Civil War, Confederate military forces were in the area until it was captured by the Union California Column in August 1862. It was then headquarters for the 5th Regiment California Volunteer Infantry from August 1863 until December 1864.[19]

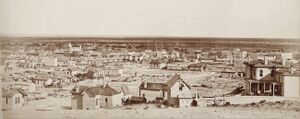

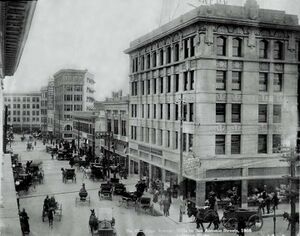

After the Civil War's conclusion, the town's population began to grow as white Texans continued to move into the villages and soon became the majority. El Paso itself, incorporated in 1873, encompassed the small area of communities that had developed along the river. In the 1870s, a population of 23 non-Hispanic Whites and 150 Hispanics was reported.[20] With the arrival of the Southern Pacific, Texas and Pacific, and Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe railroads in 1881, the population boomed to 10,000 by the 1890 census, with many Anglo-Americans, recent immigrants, old Hispanic settlers, and recent arrivals from Mexico. The location of El Paso and the arrival of these more wild newcomers caused the city to become a violent and wild boomtown known as the "Six-shooter Capital" because of its lawlessness.[17] Indeed, prostitution and gambling flourished until World War I when the Department of the Army pressured El Paso authorities to crack down on vice (thus "benefitting" vice in neighboring Ciudad Juárez). With the suppression of the vice trade and in consideration of the city's geographic position, the city continued into developing as a premier manufacturing, transportation, and retail center of the U.S. Southwest.[20]

1900–الحاضر

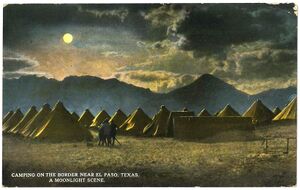

In 1909, the El Paso Chamber of Commerce hosted U.S. President William Howard Taft and Mexican President Porfirio Díaz at a planned summit in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, a historic first meeting between the Presidents of the two countries, and also the first time an American President crossed the border into Mexico.[21] However, tensions rose on both sides of the border, including threats of assassination; so the Texas Rangers, 4,000 U.S. and Mexican troops, U.S. Secret Service agents, FBI agents, and U.S. marshals were all called in to provide security.[22] Frederick Russell Burnham, a celebrated scout, was put in charge of a 250-strong private security detail hired by John Hays Hammond, who in addition to owning large investments in Mexico, was a close friend of Taft from Yale and a U.S. vice presidential candidate in 1908.[23][24] On October 16, the day of the summit, Burnham and Private C.R. Moore, a Texas Ranger, discovered a man holding a concealed palm pistol standing at the Chamber of Commerce building along the procession route in El Paso.[25][26] Burnham and Moore captured, disarmed, and arrested the assassin within only a few feet of Taft and Díaz.[27][28] By 1910, an overwhelming number of people in the city were Americans, creating a settled environment, but this period was short-lived as the Mexican Revolution greatly impacted the city, bringing an influx of refugees—and capital—to the bustling boom town. Spanish-language newspapers, theaters, movie houses, and schools were established, many supported by a thriving Mexican refugee middle class. Large numbers of clerics, intellectuals, and businessmen took refuge in the city, particularly between 1913 and 1915. Ultimately, the violence of the Mexican Revolution followed the large Mexican diaspora, who had fled to El Paso. In 1915 and again in 1916 and 1917, various Mexican revolutionary societies planned, staged, and launched violent attacks against both Texans and their political Mexican opponents in El Paso. This state of affairs eventually led to the vast Plan de San Diego, which resulted in the murder of 21 American citizens.[29] The subsequent reprisals by a local militia soon caused an escalation of violence, wherein an estimated 300 Mexicans and Mexican-Americans lost their lives. These actions affected almost every resident of the entire Rio Grande Valley, resulting in millions of dollars of losses; the result of the Plan of San Diego was long-standing enmity between the two ethnic groups.[29]

Simultaneously, other Texans and Americans gravitated to the city, and by 1920, along with the U.S. Army troops, the population exceeded 100,000, and non-Hispanic Whites once again were in the clear majority. Nonetheless, the city increased the segregation between Mexicans and Mexican-Americans with non-Hispanic Whites. One prominent form of segregation, in the form of immigration controls to prevent disease, allegedly was abused to create nonconsensual pornographic images of women distributed in local bars.[30] These rumors along with the perceived hazard from kerosene baths led to the 1917 Bath riots.[31] As a result of the increased segregation, the Catholic Church attempted to garner the Mexican-American community's allegiance through education and political and civic involvement organizations, including the National Catholic Welfare Fund.[32] In 1916, the Census Bureau reported El Paso's population as 53% Mexican and 44% Non-Hispanic whites.[33] Mining and other industries gradually developed in the area. The El Paso and Northeastern Railway was chartered in 1897, to help extract the natural resources of surrounding areas, especially in southeastern New Mexico Territory. The 1920s and 1930s had the emergence of major business development in the city, partially enabled by Prohibition-era bootlegging.[17] The military demobilization, and agricultural economic depression, which hit places like El Paso first before the larger Great Depression was felt in the big cities, though, hit the city hard. In turn, as in the rest of the United States, the Depression era overall hit the city hard, and El Paso's population declined through the end of World War II, with most of the population losses coming from the non-Hispanic White community. Nonetheless, they remained the majority to the 1940s.[citation needed]

During and following the war, military expansion in the area, as well as oil discoveries in the Permian Basin, helped to engender rapid economic expansion in the mid-1900s. Copper smelting, oil refining, and the proliferation of low-wage industries (particularly garment making) led to the city's growth. Additionally, the departure of the region's rural population, which was mostly non-Hispanic White, to cities like El Paso, brought a short-term burst of capital and labor, but this was balanced by additional departures of middle-class Americans to other parts of the country that offered new and better-paying jobs. In turn, local businesses looked south to the opportunities afforded by cheap Mexican labor. Furthermore, the period from 1942 to 1956 had the bracero program, which brought cheap Mexican labor into the rural area to replace the losses of the non-Hispanic White population. In turn, seeking better-paying jobs, these migrants also moved to El Paso. By 1965, Hispanics once again were a majority. Meanwhile, the postwar expansion slowed again in the 1960s, but the city continued to grow with the annexation of surrounding neighborhoods and in large part because of its significant economic relationship with Mexico.[citation needed]

The Farah Strike, 1972–1974, occurred in El Paso, Texas. This strike was originated and led by Chicanas, or Mexican-American women, against the Farah Manufacturing Company, due to complaints against the company inadequately compensating workers.[34] Texas Monthly described the Farah Strike as the "strike of the century".[35]

On August 3, 2019, a terrorist shooter espousing white supremacy killed 23 people at a Walmart and injured 22 others.[36][37][38][39]

الجغرافيا

El Paso is located at the intersection of three states (Chihuahua, New Mexico, and Texas) and two countries (Mexico and the U.S.). It is the only major Texas city in the Mountain Time Zone. Ciudad Juarez was once in the Central Time Zone,[40] but both cities are now on Mountain Time. El Paso is closer to the capital cities of four other states: Phoenix, Arizona (430 ميل (690 km) away);[41] Santa Fe, New Mexico (273 ميل (439 km) away);[42] Ciudad Chihuahua, Chihuahua, (218 ميل (351 km) away),[43] and Hermosillo, Sonora (325 ميل (523 km) away)[44]—than it is to the capital of its own state, Austin (528 ميل (850 km) away).[45] It is closer to Los Angeles, California (700 ميل (1،100 km) away)[46] than it is to Orange, Texas (858 ميل (1،381 km) away),[47] the easternmost town in the same state as this city.

El Paso is located within the Chihuahuan Desert, the easternmost section of the Basin and Range Region. The Franklin Mountains extend into El Paso from the north and nearly divide the city into two sections; the west side forms the beginnings of the Mesilla Valley, and the east side expands into the desert and lower valley. They connect in the central business district at the southern end of the mountain range.

The city's elevation is 3،740 ft (1،140 m) above sea level. North Franklin Mountain is the highest peak in the city at 7،192 ft (2،192 m) above sea level. The peak can be seen from 60 mi (100 km) in all directions. Additionally, this mountain range is home to the famous natural red-clay formation, the Thunderbird, from which the local Coronado High School gets its mascot's name. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 256.3 sq mi (663.7 km2).[48]

The 24،000-acre (9،700 ha) Franklin Mountains State Park, one of the largest urban parks in the United States, lies entirely in El Paso, extending from the north and dividing the city into several sections along with Fort Bliss and El Paso International Airport.

The Rio Grande Rift, which passes around the southern end of the Franklin Mountains, is where the Rio Grande flows. The river defines the border between El Paso and Ciudad Juárez to the south and west until the river turns north of the border with Mexico, separating El Paso from Doña Ana County, New Mexico. Mt. Cristo Rey, an example of a pluton, rises within the Rio Grande Rift just to the west of El Paso on the New Mexico side of the Rio Grande. Nearby volcanic features include Kilbourne Hole and Hunt's Hole, which are Maar volcanic craters 30 ميل (50 km) west of the Franklin Mountains.

On November 8, 2023, a 5.3 magnitude Earthquake struck the El Paso region. The epicenter of the earthquake was 22 miles (35 kilometers) southwest of Mentone, according to the USGS[49][50]

Cityscape

Tallest buildings

| Rank | Building | Height | Floors | Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WestStar Tower | 314 ft (96 m)[51] | 20 | 2021 | |

| 2 | Wells Fargo Plaza | 302 ft (92 m)[51] | 21 | 1971 | |

| 3 | One San Jacinto Plaza | 280 ft (85 m)[52] | 20 | 1962 | |

| 4 | Stanton Tower | 260 ft (79 m)[52] | 18 | 1982 | |

| 5 | Plaza Hotel | 246 ft (75 m) | 19 | 1930 | |

| 6 | Hotel Paso del Norte Tower | 230 ft (70 m) | 17 | 1986 | |

| 7 | El Paso County Courthouse | 230 ft (70 m) | 14[53] | 1991 | |

| 8 | Blue Flame Building | 230 ft (70 m) | 18 | 1954 | |

| 9 | O. T. Bassett Tower – Aloft Hotel | 216 ft (66 m) | 15 | 1930 | |

| 10 | One Texas Tower | 205 ft (62 m) | 15 | 1921 | |

| 11 | Albert Armendariz Sr. U.S. Federal Courthouse | 205 ft (62 m) | 9[54] | 2010 |

El Paso's second-tallest building, the Wells Fargo Plaza, was built in the early 1970s as State National Plaza. The black-windowed, 302-قدم (92 m)[51] building is famous for its 13 white horizontal lights (18 lights per row on the east and west sides of the building, and seven bulbs per row on the north and south sides) that were lit at night. The tower did use a design of the United States flag during the July 4 holidays, as well as the American hostage crisis of 1980, and was lit continuously following the September 11 attacks in 2001 until around 2006. During the Christmas holidays, a design of a Christmas tree was used, and at times, the letters "UTEP" were used to support University of Texas at El Paso athletics. The tower is now only lit during the holiday months, or when special events take place in the city.

Neighborhoods

Downtown and central El Paso

This part of town contains some of the city's oldest and most historic neighborhoods. Located in the heart of the city, it is home to about 44,993 people.[55] Development of the area started in 1827 with the first resident, Juan Maria Ponce de Leon, a wealthy merchant from Paso del Norte (present-day Ciudad Juárez), who built the region's first structure establishing Rancho Ponce within the vicinity of S. El Paso Street and Paisano Dr. when the city was barely beginning. Today, central El Paso has grown into the center of the city's economy and a thriving urban community. It contains numerous historic sites and landmarks, many in the Sunset Heights district. Other historic districts in this area include the Rio Grade Avenue Historic District, Segundo Barrio Historic District, and the Magoffin Historic District. It is close to the El Paso International Airport, the international border, and Fort Bliss. It is part of the El Paso Independent School District.

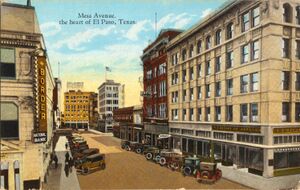

Dr. James Day, an El Paso historian, said that downtown's main business area was originally centered between Second Avenue (now Paisano Drive) and San Francisco Avenue. At a later point, the main business area was centered around Stanton Street and Santa Fe Street. In the late 1800s, most of the White American residents lived to the north of the non-White areas, living in brick residences along Magoffin, Myrtle, and San Antonio Avenues. Hispanic-American residents lived in an area called Chihuahuita ("little Chihuahua"), which was located south of Second Avenue and west of Santa Fe Street. Several African Americans and around 300 Chinese Americans also lived in Chihuahuita. Many of the Chinese Americans participated in the building of railroads in the El Paso area.[56] Another downtown neighborhood is El Segundo Barrio, which is near the Mexico–U.S. border.[57]

Northwest El Paso

Better known as West El Paso or the West Side, the area includes a portion of the Rio Grande floodplain upstream from downtown, which is known locally as the Upper Valley and is located on the west side of the Franklin Mountains. The Upper Valley is the greenest part of the county due to the Rio Grande. The West Side is home to some of the most affluent neighborhoods within the city, such as the Coronado Hills, Country Club, and Three Hills neighborhoods. It is one of the fastest-growing areas of El Paso. The main high schools in the westside include Canutillo High School, Coronado High School (El Paso, Texas), and Franklin High School (El Paso, Texas).

West-central El Paso

West-central El Paso is located north of Interstate 10 and west of the Franklin Mountains. The University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) and the Cincinnati Entertainment district are located in the heart of the area. Historic districts Kern Place and Sunset Heights are in this part of town.

Kern Place was founded in 1914 by Peter E. Kern, for whom the neighborhood was named.[58] The homes of Kern Place are unique in architecture and some were built by residents themselves.[58] One of the better known homes is the Paul Luckett Home located at 1201 Cincinnati Ave. above Madeline Park, and is made of local rock. It is known as "The Castle" due to its round walls and a crenelated rooftop.[58]

Kern Place is extremely popular with college and university students. The area is known for its glitzy entertainment district, restaurants and coffee shops that cater to both business patrons and university students.[59][60] After UTEP's basketball and football games, UTEP fans pack the Kern Place area for food and entertainment at Cincinnati Street, a small bar district. This bar scene has grown over the years and has attracted thousands to its annual Mardi Gras block party, as well as after sporting events or concerts. Young men and women make up the majority of the crowds who stop in between classes or after work.[citation needed]

Sunset Heights is one of the most historic areas in town, which has existed since the latter part of the 1890s. Many wealthy residents have had their houses and mansions built on this hill. Although some buildings have been renovated to their former glory, many have been neglected and have deteriorated. During the Mexican Revolution widely popular revolutionary leader Pancho Villa owned and resided in this area during the 1910s.[61] During the 1910 Mexican Revolution many Mexicans fled Mexico and settled in Sunset Heights.[62]

Northeast El Paso

This part of town is located north of central El Paso and east of the Franklin Mountains. Development of the area was extensive during the 1950s and 1960s. It is one of the more ethnically diverse areas in the city due to the concentration of military families. The Northeast has not developed as rapidly as other areas, such as east El Paso and northwest El Paso, but its development is steadily increasing. The population is expected to grow more rapidly as a result of the troop increase at Ft. Bliss in the coming years. The area has also gained recognition throughout the city for the outstanding high-school athletic programs at Andress High School, Parkland High School, Irvin High School, and Chapin High School.

In May 2021 a major developer announced plans for a Master Planned Community in the Northeast modeled after Scarborough's Sunfield Master Planned Community in Buda, Texas. The first phase of the development is to include about 2,500 homes, 10-acre park, walking trails, a four-acre resort-like area with a lazy river, kiddy splash pad, pool, grass areas, and a food truck area, the developers reported. Jessica Herrera, director of the city of El Paso Economic and International Development Department, in a statement released by the developers, said Campo del Sol will generate hundreds of millions of dollars in tax revenues, "which will stimulate other growth and development on the north side of town".[63]

East El Paso

The area is located north of Interstate 10, east of Airway Blvd., and south of Montana Ave. It is the largest and fastest growing area of town with a population over 200,000.[64] It includes the 79936 ZIP Code, which was considered in 2013 as the most populous in the nation with over 114,000 people.[65]

Mission Valley

Formerly known as the lower valley, it includes part of Eastside and all lower valley districts. It is the third-largest area of the city, behind east El Paso and central El Paso. Hawkins Road and Interstate 10 border the Mission Valley. This location is considered the oldest area of El Paso, dating back to the late 16th century when present-day Texas was under the rule of New Spain.

In 1680, the Isleta Pueblo tribe revolted against the Spaniards who were pushed south to what is now El Paso. Some Spaniards and tribe members settled here permanently. Soon afterward, three Spanish missions were built; they remain standing, currently functioning as churches: Ysleta Mission-1682 (La Misión de Corpus Christi y de San Antonio de la Ysleta del Sur/Our Lady of Mt. Carmel), Socorro Mission-1759 (Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción del Socorro)-1759, and San Elizario Chapel (Capilla de San Elcear)-1789.

On April 30, 1598, the northward-bound Spanish conquistadors crossed large sand dunes about 27 miles south of present-day downtown El Paso. The expeditionaries and their horses reportedly ran toward the river, and two horses drank themselves to death. Don Juan de Oñate, a New Spain-born conquistador of Spanish parents, was an expedition leader who ordered a big feast north of the Río Grande in what is now San Elizario. This was the first documented and true Thanksgiving in North America.[citation needed] Oñate declared la Toma (taking possession), claiming all territory north of the Río Grande for King Philip II of Spain.

Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo (related to the insurgent Isleta Pueblo Tribe) is also located in this valley. The Tigua is one of three Indian tribes in Texas whose sovereignty is recognized by the United States government. Ysleta is spelled with a "Y" because 19th-century script did not differentiate between a capital "Y" and a capital "I".

Some people in this area and its twin city across the river, Ciudad Juárez, are direct descendants of the Spaniards.

Texas and New Mexico suburbs

El Paso is surrounded by many cities and communities in both Texas and New Mexico. The most populated suburbs in Texas are Socorro, Horizon City, Fort Bliss, and San Elizario. Other Texas suburbs are Anthony, Canutillo, Sparks, Fabens, and Vinton.

Although Anthony, Santa Teresa, Sunland Park, and Chaparral lie adjacent to El Paso County, they are considered to be part of the Las Cruces, New Mexico metropolitan area by the United States Census Bureau.[66]

Climate

| El Paso, Texas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جدول الطقس (التفسير) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

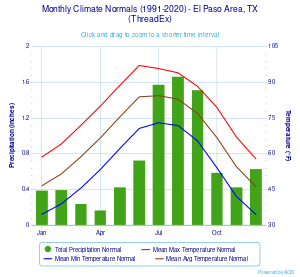

El Paso has a hot desert climate (Köppen BWh) featuring hot summers, with little humidity, and cool to mild, dry winters. Rainfall averages 8.8 in (220 mm) per year, much of which occurs from June through September, and is predominantly caused by the North American Monsoon. During this period, southerly and southeasterly winds carry moisture from the Pacific, the Gulf of California, and the Gulf of Mexico into the region. When this moisture moves into the El Paso area and places to the southwest, orographic lift from the mountains, combined with strong daytime heating, causes thunderstorms, some severe enough to produce flash flooding and hail, across the region.

The sun shines 302 days per year on average in El Paso, 83% of daylight hours, according to the National Weather Service; from this, the city is nicknamed "The Sun City".[68] Due to its arid, windy climate, El Paso often experiences sand and dust storms during the dry season, particularly during the springtime between March and early May. With an average wind speed often exceeding 30 mph (50 km/h) and gusts that have been measured at over 75 mph (120 km/h), these wind storms kick up large amounts of sand and dust from the desert, causing loss of visibility.

El Paso and the nearby mountains also receive snow. Weather systems have produced over 1 ft (30 cm) of snow on several occasions. In the 1982–1983 winter season, three major snowstorms produced record seasonal snowfall. On December 25–26, 1982, 6.0 in (15 cm) of snow fell, producing a white Christmas for the city.[69] This was followed by another 7.0 in (18 cm) on December 30–31, 1982. On April 4–7, 1983, 16.5 in (42 cm) of snow fell on El Paso, bringing the seasonal total to nearly 30 in (76 cm). On December 13–14, 1987, a record storm dumped over 22 in (56 cm) of snow on El Paso, and two weeks later (December 25–26), another 3 in (7.6 cm) fell, bringing the monthly total for December 1987 to an all-time record high of 25.9 in (66 cm)[70] of snow.[71] The average annual snowfall for the city varies widely between different neighborhoods at different elevations, but is 2.6 in (6.6 cm) at the airport (but with a median of 0, meaning most years see no snow at all).[72] Snow is most rare around Ysleta and the eastern valley area, which usually include large numbers of palm trees; in the higher neighborhoods, palm trees are more vulnerable to snow and cold snaps and are often seen with brown, frost-damaged fronds.

One example of El Paso's varying climate at its most extreme was the damaging winter storm of early February 2011, which caused closures of schools, businesses, and City Hall. The snow, which was light, stopped after about a day, but during the ensuing cold episode, municipal utilities went into a crisis. The high temperature on February 2, 2011, was 15 °F (−9 °C), the lowest daily maximum on record. In addition, the low temperature on February 3 was 1 °F (−17 °C), breaking the 5 °F (−15 °C) monthly record low set during the cold wave of 1899.[69] Loss of desert vegetation, such as Mexican/California palm trees, oleanders, and iceplants to the cold weather was one of the results. Two local power plants failed, forcing El Paso Electric to institute rolling blackouts over several days,[73] and electric wires were broken, causing localized blackouts. Many water utility pipes froze, causing areas of the city to be without water for several days.

Monthly means range from 46.1 °F (7.8 °C) in December to 84.4 °F (29.1 °C) in July, but high temperatures typically peak in June before the monsoon arrives, while daily low temperatures typically peak in July or early August with the higher humidity the monsoon brings (translating to warmer nights). On average, 42 night lows are at or below freezing, with 118 days of 90 °F (32 °C)+ highs and 28 days of 100 °F (38 °C)+ highs annually; extremely rarely do temperatures stay below the freezing mark all day.[71] The city's record high is 114 °F (46 °C) on June 30, 1994, and its record low is −8 °F (−22 °C) on January 11, 1962; the highest daily minimum was 85 °F (29 °C) on July 1 and 3, 1994, with weather records for the area maintained by the National Weather Service since 1879.

Flooding

Although the average annual rainfall is only about 8.8 in (225 mm), many parts of El Paso are subject to occasional flooding during intense summer monsoonal thunderstorms. In late July and early August 2006, up to 10 in (250 mm) of rain fell in a week, the flood-control reservoirs overflowed and caused major flooding citywide.[74] The city staff estimated damage to public infrastructure at $21 million, and to private property (residential and commercial) at $77 million.[75] Much of the damage was associated with development in recent decades in arroyos protected by flood-control dams and reservoirs, and the absence of any storm drain utility in the city to handle the flow of rain water.

| بيانات المناخ لـ El Paso Int'l, Texas (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1879–present)[أ] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| القصوى القياسية °ف (°س) | 80 (27) |

86 (30) |

93 (34) |

98 (37) |

105 (41) |

114 (46) |

112 (44) |

112 (44) |

104 (40) |

96 (36) |

87 (31) |

80 (27) |

114 (46) |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °ف (°س) | 58.6 (14.8) |

64.1 (17.8) |

71.9 (22.2) |

80.0 (26.7) |

88.7 (31.5) |

97.1 (36.2) |

95.8 (35.4) |

94.0 (34.4) |

88.3 (31.3) |

79.4 (26.3) |

67.0 (19.4) |

57.8 (14.3) |

78.6 (25.9) |

| المتوسط اليومي °ف (°س) | 46.5 (8.1) |

51.5 (10.8) |

58.7 (14.8) |

66.6 (19.2) |

75.4 (24.1) |

83.9 (28.8) |

84.4 (29.1) |

82.9 (28.3) |

76.9 (24.9) |

66.7 (19.3) |

54.5 (12.5) |

46.1 (7.8) |

66.2 (19.0) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °ف (°س) | 34.5 (1.4) |

38.9 (3.8) |

45.5 (7.5) |

53.3 (11.8) |

62.1 (16.7) |

70.6 (21.4) |

73.0 (22.8) |

71.8 (22.1) |

65.4 (18.6) |

54.0 (12.2) |

42.0 (5.6) |

34.4 (1.3) |

53.8 (12.1) |

| متوسط الدنيا °ف (°س) | 19.1 (−7.2) |

22.6 (−5.2) |

27.6 (−2.4) |

35.8 (2.1) |

46.7 (8.2) |

56.6 (13.7) |

63.9 (17.7) |

62.8 (17.1) |

52.6 (11.4) |

37.8 (3.2) |

25.1 (−3.8) |

17.9 (−7.8) |

15.6 (−9.1) |

| الصغرى القياسية °ف (°س) | −8 (−22) |

1 (−17) |

14 (−10) |

23 (−5) |

31 (−1) |

46 (8) |

56 (13) |

52 (11) |

41 (5) |

25 (−4) |

1 (−17) |

−5 (−21) |

−8 (−22) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار inches (mm) | 0.39 (9.9) |

0.40 (10) |

0.24 (6.1) |

0.17 (4.3) |

0.43 (11) |

0.73 (19) |

1.58 (40) |

1.67 (42) |

1.52 (39) |

0.59 (15) |

0.43 (11) |

0.63 (16) |

8.78 (223) |

| متوسط هطول الثلج inches (cm) | 0.8 (2.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (1.3) |

1.3 (3.3) |

2.8 (7.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3.3 | 3.1 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 8.1 | 7.8 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 47.6 |

| متوسط الرطوبة النسبية (%) | 50.5 | 41.6 | 32.4 | 26.9 | 27.1 | 29.9 | 43.9 | 48.4 | 50.5 | 47.1 | 46.1 | 51.5 | 41.3 |

| متوسط نقطة الندى °ف (°س) | 23.4 (−4.8) |

23.0 (−5.0) |

22.8 (−5.1) |

25.5 (−3.6) |

32.4 (0.2) |

41.9 (5.5) |

54.9 (12.7) |

55.8 (13.2) |

51.6 (10.9) |

39.9 (4.4) |

29.3 (−1.5) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

35.4 (1.9) |

| Mean monthly ساعات سطوع الشمس | 254.5 | 263.0 | 326.0 | 348.0 | 384.7 | 384.1 | 360.2 | 335.4 | 304.1 | 298.6 | 257.6 | 246.3 | 3٬762٫5 |

| نسبة السطوع المحتمل للشمس | 80 | 85 | 88 | 89 | 90 | 90 | 83 | 81 | 82 | 85 | 82 | 79 | 85 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity 1962–1990, sun 1961–1990, dew point 1962–1990)[69][76][77] | |||||||||||||

See or edit raw graph data.

المناخ

درجات الحرارة

| متوسطات الطقس لإل پاسو | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| شهر | يناير | فبراير | مارس | أبريل | مايو | يونيو | يوليو | أغسطس | سبتمبر | اكتوبر | نوفمبر | ديسمبر | السنة |

| العظمى القياسية °F (°C) | 80 (27) | 83 (28) | 89 (32) | 98 (37) | 105 (41) | 114 (46) | 112 (44) | 108 (42) | 104 (40) | 96 (36) | 87 (31) | 80 (27) | 114 (46) |

| متوسط العظمى °ف (°م) | 57 (14) | 63 (17) | 70 (21) | 79 (26) | 87 (31) | 96 (36) | 95 (35) | 93 (34) | 88 (31) | 79 (26) | 66 (19) | 58 (14) | 78 (26) |

| متوسط الصغرى °ف (°م) | 31 (-1) | 35 (2) | 41 (5) | 49 (9) | 58 (14) | 66 (19) | 70 (21) | 68 (20) | 62 (17) | 50 (10) | 38 (3) | 32 (0) | 50 (10) |

| الصغرى القياسية °ف (°C) | -8 (-22) | 8 (-13) | 14 (-10) | 23 (-5) | 31 (-1) | 46 (8) | 57 (14) | 56 (13) | 42 (6) | 25 (-4) | 1 (-17) | 5 (-15) | −8 (−22) |

| هطول الأمطار بوصة (mm) | 0.44 (11.2) | 0.43 (10.9) | 0.39 (9.9) | 0.25 (6.4) | 0.28 (7.1) | 0.69 (17.5) | 1.62 (41.1) | 1.54 (39.1) | 1.39 (35.3) | 0.73 (18.5) | 0.33 (8.4) | 0.55 (14) | 8٫64 (219٫5) |

| المصدر: {{{source}}} {{{accessdate}}} | |||||||||||||

العمارة

أعلى 10 مباني في إل پاسو

| الترتيب | الاسم | الارتفاع | الطبقات |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wells Fargo Plaza | 296 أقدام (90 m) | 21 |

| 2 | Chase Tower | 250 أقدام (76 m) | 20 |

| 3 | Plaza Hotel | 239 أقدام (73 m) | 19 |

| 4 | Kayser Building | 232 أقدام (71 m) | 20 |

| 5 | El Paso Natural Gas Company Building | 208 أقدام (63 m) | 18 |

| 6 | Camino Real Hotel | 205 أقدام (62 m) | 17 |

| 7 | Doubletree Hotel | 202 أقدام (62 m) | 17 |

| 8 | O. T. Bassett Tower | 196 أقدام (60 m) | 15 |

| 9 | El Paso County Courthouse | 185 أقدام (56 m) | 13 |

| 10 | Anson Mills Building | 145 أقدام (44 m) | 12 |

الحكومة

الاقتصاد

| # | Employer | Number of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fort Bliss | 47,628 |

| 2 | El Paso Independent School District | 7,875 |

| 3 | Socorro Independent School District | 7,195 |

| 4 | City of El Paso | 6,840 |

| 5 | T&T Staff Management | 6,187 |

| 6 | Ysleta Independent School District | 6,022 |

| 7 | The Hospitals of Providence | 5,300 |

| 8 | University of Texas at El Paso | 3,170 |

| 9 | El Paso Community College | 3,102 |

| 10 | El Paso County | 2,980 |

| 11 | University Medical Center | 2,800 |

| 12 | DATAMARK Inc. | 2,800 |

| 13 | Alorica | 2,500 |

| 14 | GC Services Lp | 2,250 |

| 15 | Las Palmas Del Sol Healthcare | 2,184 |

El Paso has a diversified economy focused primarily within international trade, military, government civil service, oil and gas, health care, tourism, and service sectors. The El Paso metro area had a GDP of $29.03 billion in 2017.[79] There was also $92 billion worth of trade in 2012.[80] Over the past 15 years the city has become a significant location for American-based call centers. Cotton, fruit, vegetables, and livestock are also produced in the area. El Paso has added a significant manufacturing sector with items and goods produced that include petroleum, metals, medical devices, plastics, machinery, defense-related goods, and automotive parts. On July 22, 2020, Amazon announced plans to open the first 625,000 square foot fulfillment center in El Paso.[81] Owing to its location on a border, the city is the second-busiest international crossing point in the U.S. behind San Diego.[82]

El Paso is home to one Fortune 500 company, Western Refining, which is listed on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE).[83] This makes the city one of six Texas metro areas to have at least one Fortune 500 company call it home; the others being Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, San Antonio, Austin, and Corpus Christi.[84] The second publicly traded company is Helen of Troy Limited, a NASDAQ-listed company that manufactures personal health-care products under many labels, such as OXO, Dr. Scholl's, Vidal Sassoon, Pert Plus, Brut, and Sunbeam, and the third is El Paso Electric listed on the NYSE, a public utility engaging in the generation, transmission, and distribution of electricity in West Texas and southern New Mexico. The fourth publicly traded company is Western Refining Logistics, also traded in the NYSE. It is a Western Refining subsidiary, which owns, operates, develops, and acquires terminals, storage tanks, pipelines, and other logistics assets.

More than 70 Fortune 500 companies have offices in El Paso, including AT&T, ADP, Boeing, Charles Schwab, Delphi, Dish Network, Eureka, Hoover, Raytheon, USAA and Verizon Wireless.[85][86] Hispanic Business Magazine included 28 El Paso companies in its list of the 500 largest Hispanic owned businesses in the United States.[87] El Paso's 28 companies are second only to Miami's 57. The list of the largest Hispanic owned businesses includes companies like Fred Loya Insurance, a Hispanic 500 company and the 18th largest Hispanic business in the nation. Other companies on the list are Dos Lunas Spirits, Dynatec Labs, Spira Footwear, DATAMARK, Inc. and El Taco Tote. El Paso was home to El Paso Corporation formerly known as El Paso Natural Gas Company.

The city also has a large military presence with Fort Bliss, William Beaumont Army Medical Center, and Biggs Army Airfield. The defense industry in El Paso employs over 41,000 and provides a $6 billion annual impact to the city's economy.[88] In 2013, Fort Bliss was chosen as the newly configured U.S. Air Force Security Forces Regional Training Center which added 8,000 to 10,000 Air Force personnel annually.[89]

In addition to the military, the federal government has a strong presence in El Paso to manage its status and unique issues as an important border region. Operations headquartered in El Paso include the DEA Domestic Field Division 7, El Paso Intelligence Center, Joint Task Force North, U.S. Border Patrol El Paso Sector, and U.S. Border Patrol Special Operations Group.

Call-center operations employ more than 10,000 people in the area.[citation needed] Automatic Data Processing has an office in West El Paso, employing about 1,100 people with expansion plans to reach 2,200 by 2020.[90]

Tourism is another major industry in El Paso, bringing in $1.5 billion and over 2.3 million visitors annually due to the city's sunny weather, natural beauty, rich cultural history, and many outdoor attractions.[91]

Education is also a driving force in El Paso's economy. El Paso's three large school districts are among the largest employers in the area, employing more than 20,000 people among them. UTEP has an annual budget of nearly $418 million and employs nearly 4,800 people.[92][93] A 2010 study by the university's Institute for Policy and Economic Development stated the university's impact on local businesses is $417 million annually.[94]

الديموغرافيا

| التعداد | Pop. | ملاحظة | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 200 | — | |

| 1860 | 428 | 114�0% | |

| 1880 | 736 | — | |

| 1890 | 10٬338 | 1٬304٫6% | |

| 1900 | 15٬906 | 53٫9% | |

| 1910 | 39٬279 | 146٫9% | |

| 1920 | 77٬560 | 97٫5% | |

| 1930 | 102٬421 | 32٫1% | |

| 1940 | 96٬810 | −5٫5% | |

| 1950 | 130٬485 | 34٫8% | |

| 1960 | 276٬687 | 112�0% | |

| 1970 | 339٬615 | 22٫7% | |

| 1980 | 425٬259 | 25٫2% | |

| 1990 | 515٬342 | 21٫2% | |

| 2000 | 563٬662 | 9٫4% | |

| 2010 | 649٬121 | 15٫2% | |

| 2018 (تق.) | 682,669 | [95] | Formatting error: invalid input when rounding% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[96] Texas Almanac: 1850–2000[97] 2012 Estimate[98] El Paso 1850 to 2006[99] TX State Historical Association[100] | |||

| الملف الديموغرافي | 2017[101] | 2010[102] | 2000[103] | 1990[104] | 1970[104] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| بيض | 92.0% | 80.8% | 76.3% | 76.9% | 96.7% |

| —Non-Hispanic whites | 11.8% | 14.2% | 18.3% | 26.4% | 40.4%[105] |

| African American or Black | 3.9% | 3.4% | 3.5% | 3.4% | 2.3% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 82.8% | 80.7% | 76.6% | 69.0% | 57.3%[105] |

| Asian | 1.3% | 1.2% | 1.5% | 1.2% | 0.3% |

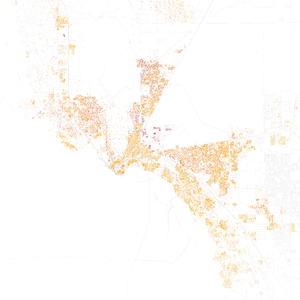

As of 2010 U.S. census, 649,121 people, 216,694 households, and 131,104 families resided in the city. The population density was 2,263.0 people per square mile (873.7/km²). There were 227,605 housing units at an average density of 777.5 per square mile (300.2/km²). Recent census estimates say that the racial composition of El Paso is: White– 92.0% (Non-Hispanic Whites: 11.8%), African American or Black – 3.9%, Two or more races – 1.5%, Asian – 1.3%, Native American – 1.0%, and Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander – 0.2%.[106] There are no de facto Anglo and African-American neighborhoods.[107]

Ethnically, the city was: 82.8% Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 216,894 households in 2010, out of which 37.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.5% were married couples living together, 20.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 25.3% were not families. About 21.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 24.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.95 and the average family size was 3.47

In the city, the population was distributed as 29.1% under the age of 18, 7.5% from 20 to 24, 26.2% from 25 to 44, 22.8% from 45 to 64, and 11.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32.5 years.

The median income for a household in the city was $44,431, and for a family was $50,247. Males had a median income of $28,989 versus $21,540 for females. The per capita income for the city was $21,120. About 17.3% of families and 20.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 28.5% of those under age 18 and 18.4% of those age 65 or over.

الرياضة

التعليم

المستشفيات

الثقافة

نقاط مهمة

المسارح

النقل

Interstate 10 The primary thoroughfare through the city, connecting the city with other major U.S. cities such as Houston, Los Angeles, New Orleans, Phoenix and Dallas (via Interstate 20). The I-10 is also a connector to Interstate 25, which connects with the cities of Albuquerque, Denver and Cheyenne.

Interstate 10 The primary thoroughfare through the city, connecting the city with other major U.S. cities such as Houston, Los Angeles, New Orleans, Phoenix and Dallas (via Interstate 20). The I-10 is also a connector to Interstate 25, which connects with the cities of Albuquerque, Denver and Cheyenne. U.S. Highway 54 Officially called the Patriot Freeway, locally known as the North-South Freeway. A business route runs along Dyer Street, the former US 54, from the freeway near Fort Bliss to the Texas-New Mexico border, where it again rejoins the expressway. The original U.S. 54 was a transcontinental route connecting El Paso with Chicago.

U.S. Highway 54 Officially called the Patriot Freeway, locally known as the North-South Freeway. A business route runs along Dyer Street, the former US 54, from the freeway near Fort Bliss to the Texas-New Mexico border, where it again rejoins the expressway. The original U.S. 54 was a transcontinental route connecting El Paso with Chicago. U.S. Highway 62 mostly Paisano Drive, rerouted to Montana Avenue.

U.S. Highway 62 mostly Paisano Drive, rerouted to Montana Avenue. U.S. Highway 85 Paisano Drive west of Santa Fe Ave to I-10.

U.S. Highway 85 Paisano Drive west of Santa Fe Ave to I-10. U.S. Highway 180 Montana Avenue, which is a bypass route to the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex to the east, and Flagstaff, Arizona to the west.

U.S. Highway 180 Montana Avenue, which is a bypass route to the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex to the east, and Flagstaff, Arizona to the west. SH 20 Alameda Avenue, formerly US 80.

SH 20 Alameda Avenue, formerly US 80. SH 178

SH 178 Loop 478 Copia Avenue to Dyer Street.

Loop 478 Copia Avenue to Dyer Street. Loop 375 Texas Highway Loop 375 encircles the city of El Paso. In the Northeast section of the city, it is Woodrow Bean Trans Mountain Drive. In East El Paso, the North- and Southbound section is known as Joe Battle Blvd., or simply as "the Loop". South of I-10, in the east and westbound portion, it is known as the Cesar Chavez Border Highway, a four-lane expressway which is located along the U.S.-Mexico border between Downtown El Paso and the Ysleta area.

Loop 375 Texas Highway Loop 375 encircles the city of El Paso. In the Northeast section of the city, it is Woodrow Bean Trans Mountain Drive. In East El Paso, the North- and Southbound section is known as Joe Battle Blvd., or simply as "the Loop". South of I-10, in the east and westbound portion, it is known as the Cesar Chavez Border Highway, a four-lane expressway which is located along the U.S.-Mexico border between Downtown El Paso and the Ysleta area.

المدن الشقيقة

– تشيواوا، المكسيك[108]

– تشيواوا، المكسيك[108] – شريش، اسپانيا[109]

– شريش، اسپانيا[109] – ميريدا، اسپانيا[109]

– ميريدا، اسپانيا[109] – خواريز، المكسيك[109]

– خواريز، المكسيك[109] – توريون، المكسيك[109]

– توريون، المكسيك[109] – زاكاتيكاس، المكسيك[109]

– زاكاتيكاس، المكسيك[109]

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

الهوامش

- ^ "Visit El Paso, Texas". El Paso Convention & Visitors Bureau. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ "El Chuco tells of El Paso pachuco history – Ramon Renteria". El Paso Times. June 30, 2013. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "QuickFacts: El Paso city, Texas". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ "2020 Population and Housing State Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Hueco Tanks State Historic Site Videos Big Bend Country Region". Archived from the original on November 22, 2007.

- ^ "American FactFinder Commuting Characteristics by Sex". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 28, 2019. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ Metz, Leon C. (1993). El Paso Chronicles: A Record of Historical Events in El Paso, Texas. El Paso: Mangan Press. ISBN 0-930208-32-3.

- ^ Chipman, Donald E. "Cabeza de Vaca, Álvar Núñez". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ Ramón A. Gutiérrez, When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away: Marriage, Sexuality, and Power in New Mexico, 1500–1846 (Stanford University Press, 1991) p. 145

- ^ أ ب ت El Paso, A Borderlands History, by W.H. Timmons, pp. 74, 75

- ^ Drexler, Ken. "Research Guides: Compromise of 1850: Primary Documents in American History: Introduction". guides.loc.gov (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- ^ "Compromise of 1850 (1850)". National Archives (in الإنجليزية). 2021-06-28. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- ^ "Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848)". U.S. National Archives, Milestone Documents. June 25, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ "El Paso". Handbook of Texas. September 21, 2023. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت El Paso, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online

- ^ أ ب Richardson, Albert D. (1867). Beyond the Mississippi : From the Great River to the Great Ocean. Hartford, Conn.: American Publishing Co. p. 238.

- ^ Orton, Richard H., ed. (1890). Records of California Men in the War of the Rebellion 1861 to 1867. Sacramento: Adjutant General's Office. p. 672. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ أ ب "elpasonext – Downtown El Paso History". Elpasotexas.gov. Archived from the original on July 5, 2009. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ Harris 2009, p. 1.

- ^ Harris 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Hampton 1910.

- ^ Daily Mail 1909, p. 7.

- ^ Harris 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Hammond 1935, pp. 565–66.

- ^ Harris 2009, p. 213.

- ^ Harris 2004, p. 26.

- ^ أ ب "Plan of San Diego". Texas State Historical Association. June 15, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- ^ "John Carlos Frey: America's Deadly Stealth War on the Mexico Border Is Approaching Genocide". Democracy Now!. July 10, 2019. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ "Women Force Anti-American Riot in Juarez (pt. 1)". Detroit Free Press. Vol. 82, no. 124. 1917-01-29. p. 1. Retrieved 2022-11-08 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Macías-González, Víctor M. (1995). Mexicans "of the better class": The elite culture and ideology of Porfirian Chihuahua and its influence on the Mexican American generation, 1876–1936. El Paso: UTEP.

- ^ Ellsworth, Emmons K., ed. (January 15, 1916). Special Census of the Population of El Paso, Tex: January 15, 1916. United States Bureau of the Census. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "Chicanos Strike At Farah" (PDF). www.marxists.org. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- ^ "The Best of the Texas Century—Business". Texas Monthly (in الإنجليزية). January 20, 2013. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- ^ "Texas Walmart shooting: Twenty killed in El Paso gun attack". BBC. August 4, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ Blankstein, Andrew; Burke, Minyvonne (August 3, 2019). "El Paso shooting: 20 people dead, 26 injured, suspect in custody, police say". NBC News. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ "El Paso Walmart Shooting Victim Dies, Death Toll Now 23". The New York Times. 2020-04-26. Archived from the original on 27 Apr 2020. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "Texas Man Pleads Guilty to 90 Federal Hate Crimes and Firearms Violations for August 2019 Mass Shooting at Walmart in El Paso, Texas". www.justice.gov. February 8, 2023.

- ^ "Time changes in Chihuahua". Timeanddate.com. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "Distance from El Paso, TX to Phoenix, AZ". check-distance.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ "Distance from El Paso, TX to Santa Fe, NM". check-distance.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ "Distance from El Paso, TX, USA to Chihuahua, Mexico" (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on December 2, 2018. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ "Distance from El Paso, TX, USA to Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico" (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on December 2, 2018. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ "Distance from El Paso, TX to Austin, TX". check-distance.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ "Distance from El Paso, TX to Los Angeles, CA". check-distance.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ "Distance from El Paso, TX to Orange, TX". check-distance.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): El Paso city, Texas". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ^ "Texas earthquake - el Paso houses shake as USGS records 5.3 magnitude tremor". November 8, 2023.

- ^ "Earthquake in el Paso? 5.3 magnitude quake hits West Texas early Wednesday". November 9, 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت Aaron Montes (May 14, 2018). "It's now 18 stories: Downtown tower plan gets big upgrade". El Paso Inc.

- ^ أ ب "El Paso – Statistics – EMPORIS". Emporis. Archived from the original on May 19, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "El Paso County Historical Commission". Archived from the original on May 29, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ^ "Overview". Archived from the original on September 17, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ^ "Population of Central, El Paso, Texas". Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Metz, Leon. "Downtown El Paso has colorful history Archived يوليو 31, 2012 at archive.today." El Paso Times. November 30, 2006. Retrieved on March 6, 2010.

- ^ "11 Most Endangered: Chihuahuita and El Segundo Barrio". National Trust for Historic Preservation (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on April 19, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ أ ب ت Magruder, Alicia; Dickey, Gretchen (2004). "Kern Place Neighborhood: The Man Behind a Name". Borderlands. 23.

- ^ Gray, Robert (July 5, 2016). "Cincinnati Street claws back losses". El Paso Inc. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ Gray, Robert (September 14, 2015). "Vacancies trouble Cincinnati district". El Paso Inc. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ Worthington, Patricia. El Paso and the Mexican Revolution. Arcadia Publishing, 2010, p. 20.

- ^ Corchado, Alfredo. "Families, businesses flee Juárez for U.S. pastures." The Dallas Morning News. Sunday March 7, 2010. Retrieved on March 10, 2010.

- ^ Kolenc, Vic. "Billionaire Paul Foster ready to develop huge residential community in Northeast El Paso". Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ "Census Explorer". census.gov. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- ^ "The ZIP Code Turns 50 Today; Here Are 9 That Stand Out". NPR. 2013. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Zipcode 79916". www.plantmaps.com. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ Rincón, Carlos A. (2002). "Solving Transboundary Air Quality Problems in the Paso Del Norte Region". In Fernandez, Linda; Carson, Richard (eds.). Both Sides of the Border. Springer. ISBN 1-4020-7126-4.

- ^ أ ب ت "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 7, 2012.

- ^ "El Paso Heavy Snow Events". Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- ^ أ ب "Climatography of the United States No. 20: El Paso Intl AP, TX 1971–2000" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on سبتمبر 7, 2013. Retrieved أبريل 27, 2010.

- ^ "National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) formerly known as National Climatic Data Center (NCDC) – NCEI offers access to the most significant archives of oceanic, atmospheric, geophysical and coastal data" (PDF). noaa.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 12, 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- ^ "Rolling Blackouts Resume Friday Morning". February 4, 2011. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ J. Rogash; M. Hardiman; D. Novlan; T. Brice; V. MacBlain. "Meteorological Aspects of the 2006 El Paso Texas Metropolitan Area Floods". NOAA/National Weather Service, Weather Forecast Office, Santa Teresa, New Mexico/El Paso, Texas.

- ^ "Storm 2006 Hits El Paso". www.elpasotexas.gov. 2006. Archived from the original on May 20, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". NOAA. 2023-06-16. Archived from the original on 2023-06-16.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for El Paso/Int'l Arpt TX 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 2023-06-16. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- ^ El Paso Inc. Book of Lists (2021 Lists ed.). El Paso Inc. 2021. p. 58.

- ^ "Bureau of Economic Analysis Gross Domestic Income by Metropolitan Area 2017" (PDF). Bureau of Economic Analysis. September 18, 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 9, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ "Mayor John Cook The Exit Interview". El Paso Inc. June 9, 2013. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ^ "El Paso Fulfilmment". Amazon. July 22, 2020. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ "Top Ports of Border Crossings". RITA. 2013. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ^ "Fortune 500 Headquarters in Texas – Office of the Governor Economic Development and Tourism" (PDF). Fortune 500. May 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2013. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ "FORTUNE 500 Headquarters in Texas – Office of the Governor Economic Development and Tourism" (PDF). Fortune Magazine. مايو 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on يونيو 15, 2013. Retrieved يونيو 29, 2013.

- ^ "El Paso: Economy – Major Industries and Commercial Activity". www.City-Data.com. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ^ "Charles Schwab to bring 445 jobs to El Paso". El Paso Times. July 24, 2014. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ "El Paso's 28 companies second in nation for Hispanic Business 500". El Paso Times. July 30, 2013. Archived from the original on August 25, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ "Fort Bliss, Beaumont infuse $6 billion into El Paso economy". El Paso Times. March 8, 2013. Archived from the original on August 25, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Air Force chooses Ft. Bliss for training center". KVIA. June 27, 2013. Archived from the original on August 25, 2013. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ "ADP plans to add 1,100 jobs in El Paso by 2020". El Paso Times. September 12, 2014. Archived from the original on September 12, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ^ "Convention and Tourism Highlights – City of El Paso FY2013 Manager's Proposed Budget" (PDF). El Paso Convention & Visitor's Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 22, 2014. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ [3][dead link]

- ^ "A University on the Move-Becoming the first National Research University with a 21st-century student demographic" (PDF). utsystem.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 29, 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ "QuickFacts". Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 8, 2006. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Texas Almanac: City Population History 1850–2000" (PDF). Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012" (CSV). Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "El Paso–Juarez Regional Historic Population Summary – Development Services Department, Planning Division" (PDF). PDF. Archived from the original (PDF) on ديسمبر 19, 2011. Retrieved سبتمبر 22, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Texas State Historical Association". June 12, 2010. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "United States Census Quick Facts". census.gov. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- ^ "El Paso (city), Texas". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on مايو 8, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on سبتمبر 4, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب "Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب From 15% sample

- ^ "State & County QuickFacts – U.S Census Bureau". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on مايو 8, 2013. Retrieved مايو 23, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "State & County QuickFacts – U.S Census Bureau". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on مايو 8, 2013. Retrieved مايو 23, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

"City Council Meetings - Voting Items". City of El Paso. 2008-11-18. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

ADDN1A. MAYOR AND COUNCIL: Discussion and action to authorize the Mayor to sign a Sister City agreement with the City of Chihuahua, Mexico reaffirming the commitment made in 2002. ACTION TAKEN: AUTHORIZED

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج

Andrade, Robert (2007). "Sister Cities". ¿Qué Pasa? A biweekly electronic newsletter from Mayor Cook. City of El Paso. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

Currently on record, there are four Sister Cities, three in Mexico (Ciudad Juarez, Zacatecas and Torreon) and one in Spain (Jerez).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

وصلات خارجية

- City of El Paso Website

- Chamber of Commerce Website

- Forty years at El Paso, 1858–1898; recollections of war, politics, adventure, events, narratives, sketches, etc., by W. W. Mills, hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- El Paso Metropolitan Planning Organization

- El Paso Mortgage Company

- El Paso, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online

- El Paso - The Best Little Music City in Texas, from Vanity Fair, March 2009.

قالب:El Pasoقالب:El Paso TVقالب:El Paso Radio قالب:El Paso Texas Museums قالب:El Paso County, Texas

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- صفحات بها مخططات

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- Webarchive template archiveis links

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Articles with dead external links from September 2017

- Articles with dead external links from December 2016

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2013

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2017

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2021

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2016

- Pages using US Census population needing update

- Pages with empty portal template

- إل پاسو، تكساس

- مدن تكساس

- مقاعد مقاطعة في تكساس

- مقاطعة إل پاسو، تكساس

- Texas communities with Hispanic majority populations

- مدن تأسست في 1659

- بلدات الحدود الأمريكية المكسيكية