بيروبيجان

{{ safesubst:#invoke:Unsubst||date=__DATE__|$B=

بيروبيجان

Биробиджан | |

|---|---|

| الترجمة اللفظية بالـ Other | |

| • Yiddish | ביראָבידזשאן |

| |

| الإحداثيات: 48°48′N 132°56′E / 48.800°N 132.933°E | |

| البلد | روسيا |

| الكيان الاتحادي | Jewish Autonomous Oblast[1] |

| Founded | 1931[2] |

| Town status since | 1937[2] |

| الحكومة | |

| • الكيان | Town Duma[3] |

| • Mayor[3] | Aleksandr Golovaty[4] |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 169٫38 كم² (65٫40 ميل²) |

| المنسوب | 80 m (260 ft) |

| التعداد | |

| • الإجمالي | 75٬413 |

| • Estimate (2018) | 73٬623 (−2٫4%) |

| • الترتيب | 215th in 2010 |

| • الكثافة | 450/km2 (1٬200/sq mi) |

| • Subordinated to | town of oblast significance of Birobidzhan[1] |

| • Capital of | Jewish Autonomous Oblast[1], Birobidzhansky District[1] |

| • Urban okrug | Birobidzhan Urban Okrug[7] |

| • Capital of | Birobidzhan Urban Okrug[7], Birobidzhansky Municipal District[8] |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+ ([9]) |

| Postal code(s)[10] | 679000, 679002, 679005, 679006, 679011, 679013–679017, 679700, 679801, 679950 |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 42622 |

| OKTMO ID | 99701000001 |

| Town Day | Last Saturday of May[11] |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www |

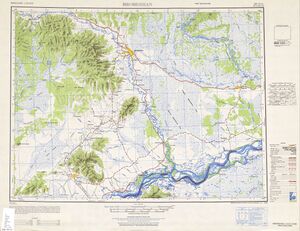

بيروبيجان (روسية: Биробиджа́н; النطق الروسي: [bʲɪrəbʲɪˈdʐan]؛ باليديشية: ביראָבידזשאַן، Birobidzhan) هي بلدة ومركز اداري للأوبلاست اليهودية الذاتية، في روسيا، وتقع على سكة الحديد عبر سيبريا، بالقرب من الحدود الروسية الصينية. وحسب تعداد 2010، يبلغ عدد سكانها 75,413 نسمة، ولغتها الرسمية هي اليديشية.[6] بيروبيجان مسماة على اسمي أكبر نهرين في الأوبلاست الذاتي: بيرا و بيجان. نهر بيرا، الذي يقع إلى الشرق من وادي بيجان، [12] يخترق البلدة. النهران روافد للآمور.

وقد أنشأها السوڤيت في اول الخمسينيات من القرن العشرون كحل شيوعى لمشكلة اليهود المطروحة والتى كانت تطالب بوطن قومي لهم. ولم تلاقى هذه التجربة الاهتمام اللازم ولم تجذب هذه المنطقة الاعداد التى كان مخطط لها من اليهود.

التاريخ

Built on the site of an earlier village called Tikhonka,[13] Birobidzhan was planned by the Swiss architect Hannes Meyer, and established in 1931. It became the administrative centre of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast in 1934, and town status was granted to it in 1937.[2] The 36,000 km2 of Birobidzhan were approved by the Politburo on March 28, 1928.[14] After the Bolshevik revolution, the Soviet government set up two organisations that worked with the settlement of Jews into Birobidzhan, the KOMZET and OZET.[15] These organisations were responsible for the distribution of land as well as domestic responsibilities, ranging from moving to medical assistance. Many Jewish Canadians then gave their support to the Soviet Union by becoming either members or sympathisers with the Communist Party of Canada.[15]

Jewish communists believed that the Soviet Union's creation of Birobidzhan was the "only true and sensible solution to the national question."[15] The Soviet government used the slogan "To the Jewish Homeland!" to encourage Jewish workers to move to Birobidzhan. The slogan proved successful in convincing Soviet Jews as well as Jews from other countries to move to the city.[16] In 1935, Ambijan received permission from the Soviet government to aid Jewish families travelling to Birobidzhan from Poland, Romania, Lithuania and Germany.[17] Jewish workers and engineers travelled to Birobidzhan from Argentina and the United States as well.[16] This campaign by the Soviet government was known as the Birobidzhan Experiment.[18]

العوامل خلف تجربة بيروبيجان

Although Birobidzhan was meant to serve as a home for the Jewish population, the authorities struggled to turn the idea into a reality. There were no important cultural connections between the land and the Jewish settlers. The growing population was culturally diverse, with some settlers focused on being modern Russian citizens, some disillusioned by modern cultures with a desire to work the land and promote socialist ideals, with few interested in establishing a cultural homeland. Ulterior motives generated by the Soviet government were the primary reasons for Jewish people to relocate to Birobidzhan. The placement of the Jews in Birobidzhan was meant to serve as a buffer to dissuade any Chinese or Japanese expansion. The region was also a link between the Trans-Siberian Railroad and the Amur River Valley, and the Soviet government sought to exploit the natural resources of the area, such as fish, timber, iron, tin, and gold.[18]

تعقيدات أثناء التجربة

Before the Russian Revolution of 1917, residence for Jews was restricted to the Pale of Settlement. As Jews relocated to Birobidzhan, they had to compete with the approximately 27,000 Russians, Cossacks, Koreans, and Ukrainians already residing there for property and land to develop new homes. This complicated the transition for the Jewish population, as there was no significant area to claim as their own.[18]

Logistically and practically, settling Birobidzhan proved to be difficult. Due to inadequate infrastructure and weather conditions of the area, more than half the Jewish settlers who relocated to Birobidzhan after the initial settlement did not remain.[19]

When the Stalinist purges began, shortly after the creation of Birobidzhan, Jews there were targeted.[20] Following World War II, tens of thousands of displaced Eastern European Jews found their way to Birobidzhan from 1946 to 1948.[21] Some were Ukrainian and Belarusian Jews who were not allowed to return to their original homes.[20] However, Jews were once again targeted in the wake of World War II when Joseph Stalin embarked on a campaign against "rootless cosmopolitans".[20] Nearly all the Yiddish institutions of Birobidzhan were liquidated.[22]

مؤيدون بارزون لبيروبيجان

Among Birobidzhan's proponents was Dudley Aman, 1st Baron Marley. After Lord Marley met Peter Smidovich and Jacob Tsegelnitski in August 1932, Marley became a proponent of Birobidzhan as a new homeland for Jewish workers and refugees. His visit to Birobidzhan in October 1933 was organised by Smidovich himself. Marley's assessment of the area was positive, and he became a more avid supporter of the settlement of Birobidzhan.[16]

Yiddish writer David Bergelson played a large part in promoting Birobidzhan, although he himself did not settle there permanently.[20] Bergelson wrote articles in the Yiddish language newspapers in other countries extolling the region as an ideal escape from antisemitism elsewhere. At least 1,000 families from the United States and Latin America came to Birobidzhan because of Bergelson. On his 68th birthday in 1952, Bergelson was among those executed during Stalin's antisemitic campaign against "rootless cosmopolitans"[20] following the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948.[20]

In the Russian language play Novaia rodina (New Homeland) by the Soviet playwright Victor Fink celebrated Birobidzhan as the coming together of three communities - the Koreans, the Amur Cossacks and the Jews. Each community has its own good and bad characters, but ultimately the good characters from each community learnt to cooperate and work with each other. To symbolise the unity achieved, the play ends with mixed marriages with one Jewish character marrying a Korean, another Jewish character marrying a Cossack and a Cossack marrying a Korean. Likewise, the Soviet Yiddish writer Emmanuil Kazakevich portrayed in a poem the achievement of Birobidzhan being declared the Jewish Autonomous Region on 7 May 1934 as an inter-communal event with the members of the Amur Cossack Host coming out to join the celebrations. Kazkevich's poem had a basis in reality as many members of the Amur Cossack Host hoped that Birobidzhan signalled Soviet interest in the neglected region along the banks of the Amur river.[23]

Canadian Arctic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson was vice president of Ambijan, or the American Committee for the Settlement of Jews in Birobidjan, which was a supplementary group that was combined with ICOR in 1946. His support of Birobidzhan as a new homeland for Jewish families consisted of appearing at meetings in support of the relocation of Jews to Birobidzhan as well as advocating for families who truly wished to travel rather than those who were the most suited for the journey.[17]

الثقافة اليهودية واليديشية

The Russian Empire had the largest Jewish population in the world in the 19th and early 20th centuries and the majority of them were Ashkenazi Jews. Large numbers of them remained even after 2 million of them departed for other countries prior to the formation of the Soviet Union. While thousands of Jews migrated to Birobidzhan, the hardship and isolation caused most to leave. In 1939 the Jewish population made up less than twenty percent of the overall population.[24] Shortly after World War II, the Jewish population in the region reached its peak of about 30,000.[22] As of the mid-2010s, only about 2,000 Jews remain in the region, making up about one half of a percent of the population.[22]

Yiddish, at that time widely regarded as the lingua franca of the Jewish community, was meant to help integrate the Jewish population into the Soviet population. The language would ensure 'national in form, socialist in content' was being followed by the Soviet Jewry.[25] Many government officials in the Kremlin were under the impression that Birobidzhan was to become the new center for Soviet Jewish life, which is why Jewish migration to Birobidzhan was strongly pushed during the 1920s.[25]

The Jewish religious community in Birobidzhan was officially registered in 1946. The religious community suffered persecution in the early 1950s.[26] Jewish culture was revived in Birobidzhan much earlier than elsewhere in the Soviet Union. Yiddish theaters opened in the 1970s. Yiddish and Jewish traditions have been required components in all public schools for almost fifteen years, taught not as Jewish exotica but as part of the region's national heritage.[27] The Birobidzhan Synagogue, completed in 2004, is next to a complex housing Sunday School classrooms, a library, a museum, and administrative offices. The buildings were officially opened in 2004 to mark the 70th anniversary of the founding of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast.[28]

According to Israeli Rabbi Mordechai Scheiner, the former Chief Rabbi of Birobidzhan and Chabad Lubavitch representative to the region, "Today one can enjoy the benefits of the Yiddish culture and not be afraid to return to their Jewish traditions. It's safe without any anti-Semitism, and we plan to open the first Jewish day school here."[29] Scheiner also hosted the Russian television show, Yiddishkeit in the region. His student, actually born in Birobidzhan, Rabbi Eliyahu Riss, has taken over the reins since 2010.

The town's synagogue opened in 2004.[30] Rabbi Scheiner says there are 4,000 Jews in Birobidzhan, just over 5 percent of the town's population of 75,000.[31] The Birobidzhan Jewish community was led by Lev Toitman, until his death in September, 2007.[32]

Concerning the Jewish community of the oblast, Governor Nikolay Mikhaylovich Volkov has stated that he intends to "support every valuable initiative maintained by our local Jewish organizations".[33] In 2007, the Birobidzhan International Summer Program for Yiddish Language and Culture was launched by Yiddish studies professor Boris Kotlerman of Bar-Ilan University.[34] The town's main street is named after the Yiddish language author and humorist Sholom Aleichem.[35]

For the Chanukah celebration of 2007, officials of Birobidzhan in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast claimed to have built the world's largest menorah.[36] A November 2017 article in The Guardian, titled, "Revival of a Soviet Zion: Birobidzhan celebrates its Jewish heritage", examined the current status of the city and suggested that, even though the Jewish Autonomous Region in Russia's far east is now barely 1% Jewish, officials hope to woo back people who left after Soviet collapse.[37]

Rabbi Eli Riss has set out to return the Jewish culture to the Jewish Autonomous Oblast. The current slogan is "make Birobidzhan Jewish again". The people want this to include teaching Yiddish in the school systems again as well as celebrating the variety of Jewish holidays. Riss' parents were originally residents of Birobidzhan, but moved to Israel in the 90's along with a large majority of the Jewish population from the Oblast. He came back as the Chief Rabbi with plans of reinvigorating the Jewish culture. There are already plans for a kosher restaurant, supermarket, and mikveh. Riss is trying to make Birobidzhan a 'safe place for Jews' and has already stated that it is one of the few places he has been where he has not experienced any anti-semitism.[38]

الوضع الإداري والبلدي

Birobidzhan is the administrative center of the autonomous oblast and, within the framework of administrative divisions, it also serves as the administrative center of Birobidzhansky District, even though it is not a part of it.[1] As an administrative division, it is incorporated separately as the town of oblast significance of Birobidzhan—an administrative unit with the status equal to that of the districts.[1] As a municipal division, the town of oblast significance of Birobidzhan is incorporated as Birobidzhan Urban Okrug.[7]

الاقتصاد والبنية التحتية والنقل

The chief economic activity is light industry, including textile and footwear. The city also has a vehicle repair factory, a furniture factory, a quicklime production factory, and several foodstuff factories. Khabarovsk is the closest major city to Birobidzhan and provides the closest major airport access to it, which is Khabarovsk Novy Airport (KHV / UHHH), 198 km from the center of Birobidzhan.

المناخ

Birobidzhan experiences a harsh, monsoon-influenced humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dwb) that is typified by very large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot (and often humid) summers and severely cold (and dry) winters.[39]

| بيانات المناخ لـ بيروبيجان | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| القصوى القياسية °س (°ف) | −0.4 (31.3) |

5.9 (42.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

29.8 (85.6) |

33.7 (92.7) |

37.1 (98.8) |

39.9 (103.8) |

36.8 (98.2) |

32.7 (90.9) |

26.9 (80.4) |

16.1 (61.0) |

5.2 (41.4) |

39.9 (103.8) |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °س (°ف) | −15.6 (3.9) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

0.2 (32.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

18.2 (64.8) |

24.5 (76.1) |

26.8 (80.2) |

24.3 (75.7) |

18.1 (64.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

| المتوسط اليومي °س (°ف) | −22.2 (−8.0) |

−16.5 (2.3) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

5.4 (41.7) |

13.0 (55.4) |

18.9 (66.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

12.8 (55.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

−18.8 (−1.8) |

1.9 (35.4) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °س (°ف) | −27.4 (−17.3) |

−26.4 (−15.5) |

−16.5 (2.3) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

5.0 (41.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

15.1 (59.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

5.9 (42.6) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−16.9 (1.6) |

−26.6 (−15.9) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

| الصغرى القياسية °س (°ف) | −43.7 (−46.7) |

−39.9 (−39.8) |

−34.1 (−29.4) |

−19.7 (−3.5) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

1.5 (34.7) |

5.9 (42.6) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−19.8 (−3.6) |

−33.6 (−28.5) |

−37.9 (−36.2) |

−43.7 (−46.7) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار mm (inches) | 6 (0.2) |

5 (0.2) |

13 (0.5) |

35 (1.4) |

61 (2.4) |

108 (4.3) |

147 (5.8) |

154 (6.1) |

88 (3.5) |

35 (1.4) |

19 (0.7) |

11 (0.4) |

682 (26.9) |

| Average precipitation days | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 84 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organisation (UN) [40] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: [www.retscreen.net/ru/home.php NASA RETScreen Database] | |||||||||||||

الرياضة

The bandy club Nadezhda[41] has been playing in the 2nd highest division, the Russian Bandy Supreme League, until the 2016–17 season.[42] However, in 2017-18 the team did not play in the league.[43]

البلدات التوأم – المدن الشقيقة

Birobidzhan is twinned with:[44]

Beaverton, United States

Beaverton, United States Niigata, Japan

Niigata, Japan Hegang, China

Hegang, China Yichun, China

Yichun, China Ma'alot-Tarshiha, Israel

Ma'alot-Tarshiha, Israel Nof HaGalil, Israel

Nof HaGalil, Israel

في الثقافة الشعبية

- Soviet Zion, أوپرا معاصرة تدور أحداثها في بيروبيجان في ع1930

- In Search of Happiness، a documentary about modern-day Birobidzhan

أشخاص بارزون

- Nataliya Gumenyuk، صحفية ومعلّمة

انظر أيضاً

- In Search of Happiness, a documentary about modern-day Birobidzhan

- Organization for Jewish Colonization in the Soviet Union (IKOR)

- History of the Jews in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast

- Beit T'shuva

- Boris "Dov" Kaufman

- Yoel Razvozov, an Israeli judoka and member of Parliament, born in Birobidzhan

المراجع

الهامش

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Law #982-OZ

- ^ أ ب ت Энциклопедия Города России. Moscow: Большая Российская Энциклопедия. 2003. p. 47. ISBN 5-7107-7399-9.

- ^ أ ب Charter of Birobidzhan, Article 16

- ^ Official website of Birobidzhan Archived أكتوبر 24, 2014 at the Wayback Machine (in روسية)

- ^ Russian Federal State Statistics Service. Economic and Social Measures of the Urban Okrugs and Urban Settlements in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast—the Town of Birobidzhan (2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011)

- ^ أ ب Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1". Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года (2010 All-Russia Population Census) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved يونيو 29, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ أ ب ت Law #226-OZ

- ^ قالب:OKTMO reference

- ^ "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). يونيو 3, 2011. Retrieved يناير 19, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Почта России. Информационно-вычислительный центр ОАСУ РПО. (Russian Post). Поиск объектов почтовой связи (Postal Objects Search) (in روسية)

- ^ Charter of Birobidzhan, Article 1

- ^ Britannica Academic, s.v. "Birobidzhan," accessed January 31, 2019, https://academic-eb-com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/levels/collegiate/article/Birobidzhan/15382.

- ^ https://www1.swarthmore.edu/Home/News/biro/html/panel09.html

- ^ Srebrnik, Henry Felix (2010). Dreams of nationhood: American Jewish communists and the Soviet Birobidzhan project, 1924-1951. Boston: Academic Studies Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-936235-11-7. OCLC 769190216.

- ^ أ ب ت Srebrnik, Henry Felix (1999). Red Star Over Birobidzhan: Canadian Jewish Communists and the "Jewish Autonomous Region" in the Soviet Union. Canadian Committee on Labour History. pp. 129–147.

- ^ أ ب ت Ivanov, Alexander (ديسمبر 2009). "Facing east: the World ORT Union and the Jewish refugee problem in Europe, 1933–38". East European Jewish Affairs. 39 (3): 369–388. doi:10.1080/13501670903298278. S2CID 144107382.

- ^ أ ب Srebrnik, Henry Felix (1998). "An idiosyncratic fellow-traveller: Vilhjalmur Stefansson and the American committee for the settlement of Jews in Birobidzhan". East European Jewish Affairs. 28, 1: 37–53. doi:10.1080/13501679808577869.

- ^ أ ب ت "Birobidzhan: Stalin's Forgotten Zion". Retrieved فبراير 17, 2019.

- ^ Skolnik, Fred; Berenbaum, Michael (2007). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA in association with the Keter Pub. House. ISBN 9780028659282. OCLC 70174939.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Gessen, Masha; Interviewed by Terry Gross (سبتمبر 7, 2016). "'Sad And Absurd': The U.S.S.R.'s Disastrous Effort To Create A Jewish Homeland" (Interview). Fresh Air. WHYY. Retrieved سبتمبر 10, 2016.

- ^ Weinberg, Robert (1998). Stalin's Forgotten Zion: Birobidzhan and the Making of a Soviet Jewish Homeland. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 72–75. ISBN 978-0-520-20990-9.

- ^ أ ب ت Pipes, Richard (أكتوبر 27, 2016). "The Sad Fate of Birobidzhan". New York Review of Books. Retrieved أكتوبر 17, 2016.

- ^ Estraikh, Gennady & Murav Harriet Soviet Jews in World War II: Fighting, Witnessing, Remembering Brighton: Academic Studies Press p.90

- ^ Slepyan, Kenneth (يناير 1, 2000). "The Soviet Partisan Movement and the Holocaust". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 14 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1093/hgs/14.1.1.

- ^ أ ب Weinberg, Robert (1996). "Jewish revival in Birobidzhan in the mirror of Birobidzhanskaya zvezda, 1946–49". East European Jewish Affairs. 26: 35–53. doi:10.1080/13501679608577817.

- ^ Kotlerman, Ber (أغسطس 2012). "If there had been no synagogue there, they would have had to invent it: the case of the Birobidzhan "religious community of the Judaic creed" on the threshold of perestroika". East European Jewish Affairs. 42 (2): 87–97. doi:10.1080/13501674.2012.699205. S2CID 159829874.

- ^ Jta.org

- ^ FJC | News | Birobidzhan - New Rabbi, New Synagogue Archived سبتمبر 27, 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wiseman, Michael C. (2010). "Birobidjan: The Story of the First Jewish State". Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse [Online]. 2 (4): 1. Retrieved سبتمبر 8, 2016.

- ^ FJC | News | Far East Community Prepares for 70th Anniversary of Jewish Autonomous Republic Archived مايو 18, 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ FJC | News | From Tractors to Torah in Russia's Jewish Land Archived أبريل 11, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Far East Jewish Community Chairman Passes Away Archived يونيو 5, 2008 at the Wayback Machine Federation of Jewish Communities

- ^ Governor Voices Support for Growing Far East Jewish Community Archived مايو 18, 2011 at the Wayback Machine Federation of Jewish Communities

- ^ 2all.co.il

- ^ Back to Birobidjan Archived أغسطس 13, 2011 at the Wayback Machine. By Rebecca Raskin. The Jerusalem Post

- ^ Breaking News - JTA, Jewish & Israel News Archived يونيو 5, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ FJC | The Guardian | Russia | Revival of a Soviet Zion: Birobidzhan celebrates its Jewish heritage | 27-September-2017

- ^ Muchnik, Andrei (نوفمبر 10, 2017). "The Other Jewish Homeland at the End of the World". Haaretz. Retrieved فبراير 21, 2012.

- ^ "ESTIMATION OF CLIMATIC RESOURCES FOR SUMMER SPORT RECREATION IN THE JEWISH AUTONOMOUS REGION OF RUSSIA". ResearchGate (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved فبراير 4, 2019.

- ^ "World Weather Information Service – Birobidzan". United Nations. Retrieved ديسمبر 31, 2010.

- ^ Hcnadezhda.narod.ru

- ^ "Надежда" Биробиджан (in الروسية). rusbandy.ru. Retrieved يوليو 20, 2015.

- ^ http://www.rusbandy.ru/news/11157/

- ^ "Города-побратимы, дружественные города". biradm.ru (in الروسية). Birobidzhan. Retrieved فبراير 5, 2020.

المصادر

- قالب:RussiaBasicLawRef/yev/birobidzhan

- قالب:RussiaAdmMunRef/yev/admlaw

- قالب:RussiaAdmMunRef/yev/munlaw/birobidzhan

للاستزادة

- S. Almazov, 10 Years of Biro-Bidjan. New York: ICOR, 1938.

- Henry Frankel, The Jews in the Soviet Union and Birobidjan. New York: American Birobidjan Committee, 1946.

- Gessen, Masha (2016). Where the Jews Aren't: The Sad and Absurd Story of Birobidzhan, Russia's Jewish Autonomous Region (Jewish Encounters Series). Schocken Books. ISBN 978-0805242461.

- Nora Levin, The Jews in the Soviet Union Since 1917: Paradox of Survival: Volume 1. New York: New York University Press, 1988.

- James N. Rosenberg, How the Back-to-the-Soil Movement Began: Two Years of Blazing the New Jewish "Covered Wagon" Trail Across the Russian Prairies. Philadelphia: United Jewish Campaign, 1925.

- Jeffrey Shandler, "Imagining Yiddishland: Language, Place and Memory," History and Memory, vol. 15, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2003), pp. 123–149. In JSTOR

- Henry Felix Srebrnik, Dreams of Nationhood: American Jewish Communists and the Soviet Birobidzhan Project, 1924-1951. Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2010.

- Robert Weinberg, "Purge and Politics in the Periphery: Birobidzhan in 1937," Slavic Review, vol. 52, no. 1 (Spring 1993), pp. 13–27. In JSTOR

- Robert Weinberg, Stalin's Forgotten Zion: Birobidzhan and the Making of a Soviet Jewish Homeland: An Illustrated History, 1928-1996. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998.

- Srebrnik, Henry Felix (2010). Dreams of Nationhood: American Jewish Communists and the Soviet Birobidzhan Project, 1924-1951. Boston: Academic Studies Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1zxsj1m. ISBN 9781618116871. JSTOR j.ctt1zxsj1m.

وصلات خارجية

- Official website of Birobizhan (in روسية)

- Birobidzhan from 1929 to 1931, photo album (digitized page images)], at the US Library of Congress

- Atlas: Birobidzhan

- The Jewish story about Birobidzhan (Birobidjan) 1928-1970 (from Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971 a.o., with photos added)

- Song about Birobidzhan

- 'Sad And Absurd': The U.S.S.R.'s Disastrous Effort To Create A Jewish Homeland (National Public Radio on September 7, 2016)

- "Birobidzhan Jewish autonomous region" (RT, 2009)

- ‘We never know if we are really accepted, or if we are playing a role', Mati Shemoelof interview in April 2021 with the Israeli-Berliner writer who wrote anovel on Birobidzhan, Plus61J

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles with روسية-language sources (ru)

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 uses الروسية-language script (ru)

- CS1 الروسية-language sources (ru)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Use mdy dates from December 2012

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- Articles containing يديشية-language text

- Infobox mapframe without OSM relation ID on Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using infobox settlement with image map1 but not image map

- Russian inhabited locality articles requiring maintenance

- بيروبيجان

- Cities and towns in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast

- الشرق الأقصى الروسي

- Populated places established in 1931

- Historic Jewish communities in Asia

- Yiddish culture in Russia

- 1931 establishments in the Soviet Union

- Koryo-saram communities

- Korean communities in Russia

- صفحات مع الخرائط