دستور اليابان

| Constitution of Japan | |

|---|---|

Preamble of the Constitution | |

| العنوان الأصلي | 日本國憲法 |

| دائرة الاختصاص | Japan |

| قـُدِّم | 3 November 1946 |

| تاريخ السريان | 3 May 1947 |

| النظام | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy[1] |

| الفروع | Three |

| رأس الدولة | None[أ] |

| الغرف | Bicameral (National Diet: House of Representatives, House of Councillors) |

| التنفيذي | Cabinet, led by a Prime Minister |

| القضائي | Supreme Court |

| الفدرالية | Unitary |

| أول مجلس تشريعي | |

| أول تنفيذي | 24 May 1947 |

| المحكمة الأولى | 4 August 1947 |

| التعديلات | 0[3] |

| الموقع | National Archives of Japan |

| المؤلف | Milo Rowell, Courtney Whitney, and other US military lawyers working for the US-led Allied GHQ; subsequently reviewed and modified by members of the Imperial Diet |

| الموقعون | Emperor Shōwa |

| يجـُبّ | Meiji Constitution |

|

|---|

|

|

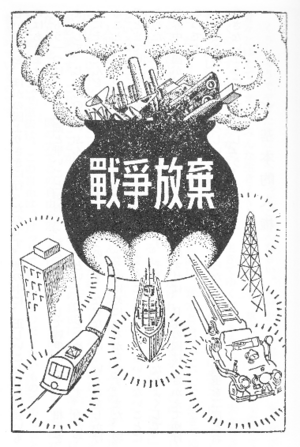

دستور اليابان[ب] هو الوثيقة الدستورية الأساسية في اليابان منذ عام 1947، يعمل الدستور على إرساء نظام برلماني للحكومة ويضمن الحقوق الأساسية. بموجب نص الدستور فإن إمبراطور اليابان هو "رمز الدولة ووحدة الشعب" وله دور رمزي دون أي سلطات حكم أو ملكية، ولذلك وعلى عكس الملوك الأخرى فهو ليس حاكم الدولة على الرغم من أنه يعامل ويحترم كما لو أنه كذلك. كما أن الدستور الحالي المعروف باسم "دستور السلام" ( 平和憲法، هيوا كينبو) بسبب دحره لفكرة إعلان الحرب في اليابان بحسب الفقرة التاسعة منه.

تم كتابة الدستور الياباني في فترة احتلال اليابان مباشرة بعد استسلام اليابان، it was adopted on 3 November 1946 and came into effect on 3 May 1947, succeeding the Meiji Constitution of 1889.[4] The constitution consists of a preamble and 103 articles grouped into 11 chapters. It is based on the principles of popular sovereignty, with the Emperor of Japan as the symbol of the state; pacifism and the renunciation of war; and individual rights.

Upon the surrender of Japan at the end of the war in 1945, Japan was occupied and U.S. General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, directed Prime Minister Kijūrō Shidehara to draft a new constitution. Shidehara created a committee of Japanese scholars for the task, but MacArthur reversed course in February 1946 and presented a draft created under his own supervision, which was reviewed and modified by the scholars before its adoption. Also known as the "MacArthur Constitution",[5][6] "Post-war Constitution" (戦後憲法, Sengo-Kenpō), or "Peace Constitution" (平和憲法, Heiwa-Kenpō),[7] it is relatively short at 5,000 signs, less than a quarter the length of the average national constitution if one compares it with constitutions written in alphabetical word-based languages.[8][9]

The constitution provides for a parliamentary system and three branches of government, with the National Diet (legislative), Cabinet led by a Prime Minister (executive), and Supreme Court (judicial) as the highest bodies of power. It guarantees individual rights, including legal equality; freedom of assembly, association, and speech; due process; and fair trial. In contrast to the Meiji Constitution, which invested the emperor with supreme political power, under the 1946 constitution his role in the system of constitutional monarchy is reduced to "the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people", and he exercises only a ceremonial role under popular sovereignty.[10] Article 9 of the constitution renounces Japan's right to wage war and to maintain military forces.[11] Despite this, it retains a de facto military in the form of the Self-Defense Forces and hosts a substantial U.S. military presence. Amendments to the constitution require a two-thirds vote in both houses of the National Diet and approval in a referendum, and despite the efforts of conservative and nationalist forces to revise Article 9 in particular, it remains the world's oldest un-amended supreme constitutional text. بهدف استبدال الملكية المطلقة العسكرية بنظام ديمقراطي ليبرالي

تاريخ

دستور ميجي

دستور اليابان الذي وضع في عام 1889 (ح. 1867–1912).[12] والمعروف باسم دستور ميجي أو الدستور الإمبراطوري كان أول دستور في اليابان الحديثة وجاء كجزء من إصلاح ميجي. في هذا الدستور فإن الإمبراطور يعتبر حاكم لليابان مدعوماً بمجلس الوزراء ورئيس الوزراء. It provided for a form of mixed constitutional and absolute monarchy, based on the Prussian and British models. In theory, the Emperor of Japan was the supreme leader, and the cabinet, whose prime minister was elected by a privy council, were his followers; in practice, the Emperor was head of state but the Prime Minister was the actual head of government. Under the Meiji Constitution, the prime minister and his cabinet were not accountable to the elected members of the Imperial Diet, and increasingly deferred to the Imperial Japanese Army in the lead-up to the Second Sino-Japanese War.

إعلان پوتسدام

On 26 July 1945, shortly before the end of World War II, Allied leaders of the United States (President Harry S. Truman), the United Kingdom (Prime Minister Winston Churchill), and the Republic of China (President Chiang Kai-shek) issued the Potsdam Declaration. The Declaration demanded Japanese military's unconditional surrender, demilitarisation and democratisation.[13]

The declaration defined the major goals of the post-surrender Allied occupation: "The Japanese Government shall remove all obstacles to the revival and strengthening of democratic tendencies among the Japanese people. Freedom of speech, of religion, and of thought, as well as respect for the fundamental human rights shall be established" (Section 10). In addition, "The occupying forces of the Allies shall be withdrawn from Japan as soon as these objectives have been accomplished and there has been established in accordance with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people a peacefully inclined and responsible government" (Section 12). The Allies sought not merely punishment or reparations from a militaristic foe, but fundamental changes in the nature of its political system. In the words of a political scientist Robert E. Ward: "The occupation was perhaps the single most exhaustively planned operation of massive and externally directed political change in world history."

The Japanese government, Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki's administration and Emperor Hirohito accepted the conditions of the Potsdam Declaration, which necessitates amendments to its Constitution after the surrender.[13]

صياغة مسودة الدستور

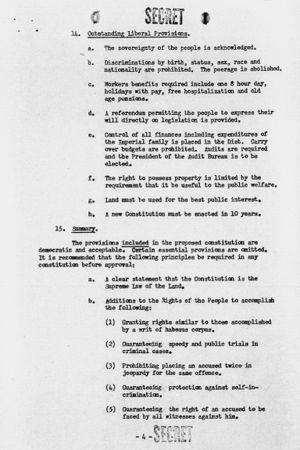

بحسب إعلان بوتسدام فإن "على اليابان إزالة كامل المعوقات..."، فإن الجنرال ماكارثر القائد الأعلى لقوات التحالف أمر عناصره بوضع مسودة للدستور الجديد بعد أن كان من الصعب على قادة اليابان التفكير بدستور قد يكون بديلاً عن دستور ميجي. على الرغم من أن كتاب مسودة الدستور الجديد لم يكونوا يابانيين إلا أنهم أخذوا بعين الاعتبار دستور ميجي ومطالب الدستوريين اليابانيين وآراء القادة السياسيين، وتم عرض مسودة الدستور على المسؤولين اليابانيين في 13 فبراير 1946، الذي أعلنت عنه الحكومة في 6 مارس من ذات العام، وفي 10 أبريل عقدت انتخابات مجلس النواب الذي من المفترض عليه أن يناقش الدستور المقترح وكانت أول انتخابات عامة يسمح فيها للنساء بالتصويت.

The MacArthur draft, which proposed a unicameral legislature, was changed at the insistence of the Japanese to allow a bicameral one, with both houses being elected. In most other important respects, the government adopted the ideas embodied in 13 February document in its own draft proposal of 6 March. These included the constitution's most distinctive features: the symbolic role of the Emperor, the prominence of guarantees of civil and human rights, and the renunciation of war. The constitution followed closely a 'model copy' prepared by MacArthur's command.[14]

In 1946, criticism of or reference to MacArthur's role in drafting the constitution could be made subject to Civil Censorship Detachment (CCD) censorship (as was any reference to censorship itself).[15] Until late 1947, CCD exerted pre-publication censorship over about 70 daily newspapers, all books, and magazines, and many other publications.[16]

اعتماد الدستور

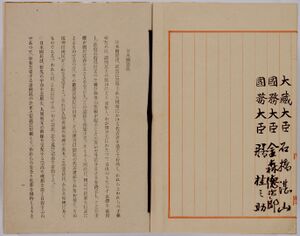

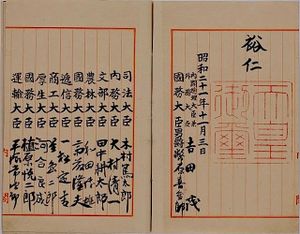

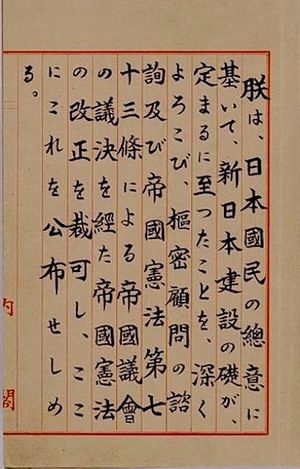

تمت مناقشة الدستور في مجلس الأعيان ومجلس النواب تم إقرار الدستور في مجلس المستشارين في 6 أكتوبر وفي اليوم التالي في مجلس النواب بخمسة أعضاء فقط صوتوا بضد، وأخيرا أصبح رسمياً بعد مصادقة الإمبراطور في 3 نوفمبر، وبدأ العمل به بعد ستة أشهر كما ينص في 3 مايو 1947.

The old constitution required that the bill receive the support of a two-thirds majority in both houses of the Diet to become law. Both chambers had made amendments. Without interference by MacArthur, House of Representatives added Article 17, which guarantees the right to sue the State for the tort of officials; Article 40, which guarantees the right to sue the State for wrongful detention; and Article 25, which guarantees the right to life.[17][18] The house also amended Article 9. The House of Peers approved the document on 6 October; the House of Representatives adopted it in the same form the following day, with only five members voting against. It became law when it received the imperial assent on 3 November 1946.[19] Under its own terms, the constitution came into effect on 3 May 1947.

A government organisation, the Kenpō Fukyū Kai ("Constitution Popularisation Society"), was established to promote the acceptance of the new constitution among the populace.[20]

نص الدستور

بنية

يتكون نص الدستور من حوالي 5000 كلمة موزعة على 103 بنود تتوزع في 11 فصل هي :

- الإمبراطور (1-8)

- التخلي عن الحرب (9)

- حقوق وواجبات الشعب (10 - 40)

- البرلمان (41 - 64)

- القضاء (76 - 82)

- المالية (83 - 91)

- الحكومات المحلية (92 - 95)

- تعديلات الدستور (96)

- محكمة عليا (97 - 99)

- تعديلات إضافية (100 - 103)

أجهزة الحكم (المواد 41–95)

التعديلات (البند 96)

Under Article 96, amendments to the constitution "shall be initiated by the Diet, through a concurring vote of two-thirds or more of all the members of each House and shall thereupon be submitted to the people for ratification, which shall require the affirmative vote of a majority of all votes cast thereon, at a special referendum or at such election as the Diet shall specify". The constitution has not been amended since its implementation in 1947, although there have been movements led by the Liberal Democratic Party to make various amendments to it.

الأحكام الأخرى (البنود 97–103)

Article 97 provides for the inviolability of fundamental human rights. Article 98 provides that the constitution takes precedence over any "law, ordinance, imperial rescript or other act of government" that offends against its provisions, and that "the treaties concluded by Japan and established laws of nations shall be faithfully observed". In most nations it is for the legislature to determine to what extent, if at all, treaties concluded by the state will be reflected in its domestic law; under Article 98, however, international law and the treaties Japan has ratified automatically form a part of domestic law. Article 99 binds the Emperor and public officials to observe the constitution.

The final four articles set forth a six-month transitional period between adoption and implementation of the Constitution. This transitional period took place from 3 November 1946, to 3 May 1947. Pursuant to Article 100, the first House of Councillors election was held during this period in April 1947, and pursuant to Article 102, half of the elected Councillors were given three-year terms. A general election was also held during this period, as a result of which several former House of Peers members moved to the House of Representatives. Article 103 provided that public officials currently in office would not be removed as a direct result of the adoption or implementation of the new Constitution.

الأحزاب السياسية

Legal status as a political party (seitō) is tied to having five members in the Diet or one member and at least two percent nationally of either proportional or majoritarian vote in one of the three elections of the current members of the National Diet, i.e. the last House of Representatives general election and the last two House of Councillors regular elections. Political parties receive public party funding (¥ 250 per citizen, about ¥ 32 bill. in total per fiscal year, distributed according to recent national elections results – last HR general and last two HC regular elections – and Diet strength on January 1), are allowed to concurrently nominate candidates for the House of Representatives in an electoral district and on a proportional list, may take political donations from legal persons, i.e. corporations, and other benefits such as air time on public broadcaster NHK.[22]

التنقيحات والتعديلات

انظر أيضاً

الدساتير السابقة

- Seventeen-article constitution (604) - rather a document of moral teachings, not a constitution in the modern meaning.

- دستور ميجي (1889)

غيرهم

- Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution

- Article 96 of the Japanese Constitution

- Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany

- Constitution Memorial Day

- Constitution of Italy

- History of Japan

- Politics of Japan

- Proposed Japanese constitutional referendum

Notes

- ^ No position for head of state is defined in constitution.[2] The Emperor of Japan is "the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people", but carries many functions of a head of state.[1]

- ^ شينجيتاي: 日本国憲法، كيوجيتاي: 日本國憲󠄁法، هبورن: Nihon-koku kenpō

- ^ 39 of the 47 governors are المستقلون.

References

- ^ أ ب Kristof, Nicholas D. (12 نوفمبر 1995). "Japan's State Symbols: Now You See Them ..." The New York Times. Retrieved 5 أكتوبر 2019.

- ^ Kakinohana, Hōjun (23 سبتمبر 2013). 個人の尊厳は憲法の基一天皇の元首化は時代に逆行一. Japan Institute of Constitutional Law (in اليابانية). Archived from the original on 25 أكتوبر 2019. Retrieved 25 أكتوبر 2019.

- ^ "The Anomalous Life of the Japanese Constitution". Nippon.com. 15 أغسطس 2017. Archived from the original on 11 أغسطس 2019. Retrieved 11 أغسطس 2019.

- ^ Goes into Effect, New Japanese Constitution (9 فبراير 2010). "May 3, 1947, New Japanese Constitution goes into effect". www.history.com. History.com Editors. Retrieved 4 مايو 2022.

- ^ Kawai, Kazuo (1958). "The Divinity of the Japanese Emperor". Political Science. 10 (2): 3–14. doi:10.1177/003231875801000201.

- ^ "The American Occupation of Japan, 1945-1952". Columbia University.

- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 11.

- ^ "The Anomalous Life of the Japanese Constitution". Nippon.com. 15 أغسطس 2017. Archived from the original on 11 أغسطس 2019. Retrieved 11 أغسطس 2019.

- ^ Ito, Masami, "Constitution again faces calls for revision to meet reality Archived 8 نوفمبر 2019 at the Wayback Machine", Japan Times, 1 May 2012, p. 3.

- ^ Takemae 2002, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 9.

- ^ Constitution, Meiji. "The Meiji Constitution". www.britannica.com. The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica History. Retrieved 4 مايو 2022.

- ^ أ ب Oda, Hiroshi (2009). "Sources of Law". Japanese Law. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199232185.001.1. ISBN 978-0-19-923218-5.

- ^ Takemae 2002, p. xxxvii.

- ^ John Dower, Embracing Defeat, p.411: "categories of deletions and suppressions" in CCD's key log in June 1946.

- ^ Dower, p. 407

- ^ Hideki SHIBUTANI(渋谷秀樹)(2013) Japanese Constitutional Law. 2nd ed.(憲法 第2版) p487 Yuhikaku Publishing(有斐閣)

- ^ "衆憲資第90号「日本国憲法の制定過程」に関する資料" (PDF). Commission on the Constitution, The House of Representatives, Japan. Retrieved 23 أغسطس 2020.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةedict - ^ "Publication and Work of the Constitution Popularization Society". Birth of the Constitution of Japan. National Diet Library of Japan. Archived from the original on 13 يونيو 2013. Retrieved 24 مايو 2013.

- ^ "Policy 政策マニフェスト". Team Mirai (in اليابانية). Retrieved 22 يوليو 2025.

- ^ Laws regulating political parties include the 公職選挙法 (Public Offices Election Act Archived 2021-10-02 at the Wayback Machine), the 政治資金規正法 (Political Funds Control Act Archived 2021-10-02 at the Wayback Machine) and the 政党助成法 (Political Parties Subsidies Act Archived 2021-10-02 at the Wayback Machine). (Note: Translations have no legal effect and are by definition "unofficial" Archived 2021-08-29 at the Wayback Machine.) Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications: s/index.html General information and published reports about political party funding (In Japanese)

وصلات خارجية

- Full text of Constitution from the Cabinet

- Birth of the Constitution of Japan

- Teruki Tsunemoto, Trends in Japanese Constitutional Law Cases: Important Judicial Decisions for 2004, trans. Daryl Takeno, Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal

- Teruki Tsunemoto, Trends in Japanese Constitutional Law Cases: Important Legal Precedents for 2005, trans. John Donovan, Yuko Funaki, and Jennifer Shimada, Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal

- Teruki Tsunemoto, Trends in Japanese Constitutional Law Cases: Important Legal Precedents for 2006, trans. Asami Miyazawa and Angela Thompson, Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal

- Teruki Tsunemoto, Trends in Japanese Constitutional Law Cases: Important Legal Precedents for 2007, trans. Mark A. Levin and Jesse Smith, Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal

- Library of Congress Country Study on Japan

- Beate Sirota Gordon (Blog about Beate Sirota Gordon and the documentary film "The Gift from Beate")

- Constitutional Revision Research Project[dead link] of the Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard University

- "新憲法草案" (PDF). Liberal Democratic Party's Center to Promote Enactment of a New Constitution website. Retrieved 3 فبراير 2006.[dead link] Shin Kenpou Sou-an, Draft New Constitution. As released by the Liberal Democratic Party on 22 November 2005. PDF format, in Japanese.

- "新憲法制定推進本部". Liberal Democratic Party website. Retrieved 3 فبراير 2006.[dead link] Web page of the Shin Kenpou Seitei Suishin Honbu, Center to Promote Enactment of a New Constitution, of the Liberal Democratic Party. In Japanese.

- "日本国憲法改正草案" (PDF). Liberal Democratic Party. Retrieved 27 ديسمبر 2012. Nihon-koku Kenpou Kaisei Souan, Amendment Draft of the Constitution of Japan. As released by the Liberal Democratic Party on 27 April 2012. PDF format, in Japanese.

- "日本国憲法改正草案Q&A" (PDF). Liberal Democratic Party. Retrieved 27 ديسمبر 2012. Nihon-koku Kenpou Kaisei Souan Q & A. As released by the Liberal Democratic Party in October 2012. PDF format, in Japanese.

- Articles containing Japanese language text

- CS1 uses اليابانية-language script (ja)

- CS1 اليابانية-language sources (ja)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- EngvarB from July 2017

- Use dmy dates from December 2018

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with broken excerpts

- Articles with dead external links from January 2013

- حكومة اليابان

- سياسة اليابان بعد الحرب

- 1947 في القانون

- دساتير اليابان

- قانون ياباني