مطيافية الامتصاص

Absorption spectroscopy is spectroscopy that involves techniques that measure the absorption of electromagnetic radiation, as a function of frequency or wavelength, due to its interaction with a sample. The sample absorbs energy, i.e., photons, from the radiating field. The intensity of the absorption varies as a function of frequency, and this variation is the absorption spectrum. Absorption spectroscopy is performed across the electromagnetic spectrum.

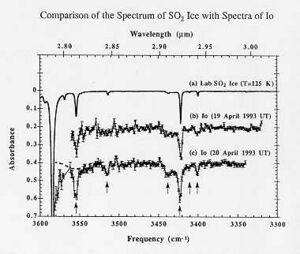

Absorption spectroscopy is employed as an analytical chemistry tool to determine the presence of a particular substance in a sample and, in many cases, to quantify the amount of the substance present. Infrared and ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy are particularly common in analytical applications. Absorption spectroscopy is also employed in studies of molecular and atomic physics, astronomical spectroscopy and remote sensing.

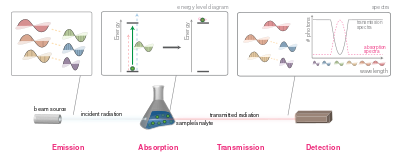

There is a wide range of experimental approaches for measuring absorption spectra. The most common arrangement is to direct a generated beam of radiation at a sample and detect the intensity of the radiation that passes through it. The transmitted energy can be used to calculate the absorption. The source, sample arrangement and detection technique vary significantly depending on the frequency range and the purpose of the experiment.

Following are the major types of absorption spectroscopy:[1]

| Sr. No | Electromagnetic radiation | Spectroscopic type |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | X-ray | X-ray absorption spectroscopy |

| 2 | Ultraviolet–visible | UV–vis absorption spectroscopy |

| 3 | Infrared | IR absorption spectroscopy |

| 4 | Microwave | Microwave absorption spectroscopy |

| 5 | Radio wave | Electron spin resonance spectroscopy |

طيف الامتصاص

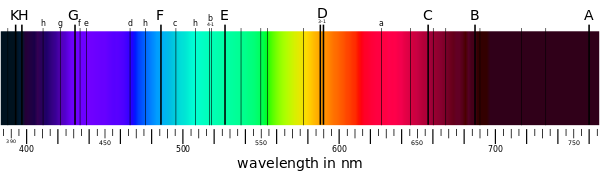

ينشأ الطيف الامتصاصي (Absorption spectrum) لعنصر عندما يمر شعاع ضوءأبيض خلال ذلك العنصر أو بخار العنصر فينتج طيف به خطوط طيف سوداء عند ترددات محددة مميزة للعنصر . والطيف الامتصاصي عو عكس طيف الإصدار الذري . ينشأ الطيف عموما عندما تثار ذرات عنصر بفعل الحرارة مثلا ، مما يجعل إلكترونات الذرة تترك مداراتها المنخفضة ذات مستوي منخفض وتنتقل إلى مستوي طاقة أعلى . لكن الإلكترون لا يسيتطيع أن يبقى طويلا في هذه الحالة المثارة ، فسرعان ما يقفز من المدار العالي الطاقة إلى مدار منخفض الطاقة ويصحب ذلك أن الإلكترون يصدر فارق طاقتي المدارالعالي والمدار المنخفض على هيئة شعاع ضوء ذي تردد محدد . وبحسب ما كانت قفزة الإلكترون من المدار الرابع مثلا إلى المدار الثاني في الذرة أو من المدار الثالث إلى المدار الأول فكل قفزة من تلك القفزات تتميز بشعاع ضوء ذي تردد محدد، وتشكل مجموع تلك الإشعاعات والتي تظهر في الطيف على هيئة خطوط ، تشكل بصمة يمكن بها معرفة العنصر الصادر منها ، إذ ان لكل عنصر طيفه وبالتالى بصمته. وفي حالة الطيف الامتصاصي فعندما ندع شعاع ضوء أبيض يتخلل بخار العنصر ، يحدث أن ذرات العنصر تمتص بصفة مميزة تلك الترددات المميزة لها ، ويظهر الطيف الناتج فاقدا لخطوط تلك الترددات ، فتبدوا كخطوط سوداء . ومن هذه يمكننا التعرف على العنصر المتسبب في هذا الامتصاص.

- يستخدم الطيف الامتصاصي في قياس الغازات الضارة بالبيئة الموجودة في الجو ، إذ يمكن به معرفة كل غاز من بين الغازات المختلطة بالهواء. كما يستعمل كثيرا في القياسات الفلكية للمجرات والدخان الكوني . كما باستطاعته تعيين ليس فقط أنواع الغازات و الجزيئات بل أيضا ًكثافة كل منها .

طرق محددة

- Cavity Ring Down Spectroscopy (CRDS)

- Mossbauer spectroscopy

- Photoemission spectroscopy

- Reflectance spectroscopy

- Laser Absorption Spectrometry (LAS)

- Tunable Diode Laser Absorption Spectroscopy (TDLAS)

- X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS)

- X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES)

- Astronomical spectroscopy

التطبيقات

Absorption spectroscopy is useful in chemical analysis[2] because of its specificity and its quantitative nature. The specificity of absorption spectra allows compounds to be distinguished from one another in a mixture, making absorption spectroscopy useful in wide variety of applications. For instance, Infrared gas analyzers can be used to identify the presence of pollutants in the air, distinguishing the pollutant from nitrogen, oxygen, water, and other expected constituents.[3]

The specificity also allows unknown samples to be identified by comparing a measured spectrum with a library of reference spectra. In many cases, it is possible to determine qualitative information about a sample even if it is not in a library. Infrared spectra, for instance, have characteristics absorption bands that indicate if carbon-hydrogen or carbon-oxygen bonds are present.

An absorption spectrum can be quantitatively related to the amount of material present using the Beer–Lambert law. Determining the absolute concentration of a compound requires knowledge of the compound's absorption coefficient. The absorption coefficient for some compounds is available from reference sources, and it can also be determined by measuring the spectrum of a calibration standard with a known concentration of the target.

الاستشعار عن بعد

One of the unique advantages of spectroscopy as an analytical technique is that measurements can be made without bringing the instrument and sample into contact. Radiation that travels between a sample and an instrument will contain the spectral information, so the measurement can be made remotely. Remote spectral sensing is valuable in many situations. For example, measurements can be made in toxic or hazardous environments without placing an operator or instrument at risk. Also, sample material does not have to be brought into contact with the instrument—preventing possible cross contamination.

Remote spectral measurements present several challenges compared to laboratory measurements. The space in between the sample of interest and the instrument may also have spectral absorptions. These absorptions can mask or confound the absorption spectrum of the sample. These background interferences may also vary over time. The source of radiation in remote measurements is often an environmental source, such as sunlight or the thermal radiation from a warm object, and this makes it necessary to distinguish spectral absorption from changes in the source spectrum.

To simplify these challenges, differential optical absorption spectroscopy has gained some popularity, as it focusses on differential absorption features and omits broad-band absorption such as aerosol extinction and extinction due to rayleigh scattering. This method is applied to ground-based, airborne, and satellite-based measurements. Some ground-based methods provide the possibility to retrieve tropospheric and stratospheric trace gas profiles.

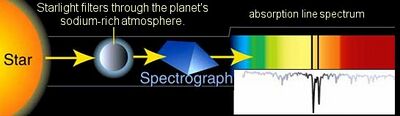

علم الفلك

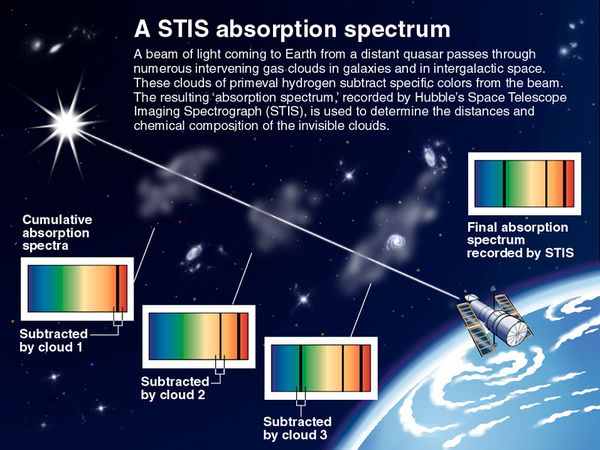

Astronomical spectroscopy is a particularly significant type of remote spectral sensing. In this case, the objects and samples of interest are so distant from earth that electromagnetic radiation is the only means available to measure them. Astronomical spectra contain both absorption and emission spectral information. Absorption spectroscopy has been particularly important for understanding interstellar clouds and determining that some of them contain molecules. Absorption spectroscopy is also employed in the study of extrasolar planets. Detection of extrasolar planets by transit photometry also measures their absorption spectrum and allows for the determination of the planet's atmospheric composition,[4] temperature, pressure, and scale height, and hence allows also for the determination of the planet's mass.[5]

Atomic and molecular physics

Theoretical models, principally quantum mechanical models, allow for the absorption spectra of atoms and molecules to be related to other physical properties such as electronic structure, atomic or molecular mass, and molecular geometry. Therefore, measurements of the absorption spectrum are used to determine these other properties. Microwave spectroscopy, for example, allows for the determination of bond lengths and angles with high precision.

In addition, spectral measurements can be used to determine the accuracy of theoretical predictions. For example, the Lamb shift measured in the hydrogen atomic absorption spectrum was not expected to exist at the time it was measured. Its discovery spurred and guided the development of quantum electrodynamics, and measurements of the Lamb shift are now used to determine the fine-structure constant.

الطرق التجريبية

المقاربة الأساسية

The most straightforward approach to absorption spectroscopy is to generate radiation with a source, measure a reference spectrum of that radiation with a detector and then re-measure the sample spectrum after placing the material of interest in between the source and detector. The two measured spectra can then be combined to determine the material's absorption spectrum. The sample spectrum alone is not sufficient to determine the absorption spectrum because it will be affected by the experimental conditions—the spectrum of the source, the absorption spectra of other materials between the source and detector, and the wavelength dependent characteristics of the detector. The reference spectrum will be affected in the same way, though, by these experimental conditions and therefore the combination yields the absorption spectrum of the material alone.

A wide variety of radiation sources are employed in order to cover the electromagnetic spectrum. For spectroscopy, it is generally desirable for a source to cover a broad swath of wavelengths in order to measure a broad region of the absorption spectrum. Some sources inherently emit a broad spectrum. Examples of these include globars or other black body sources in the infrared, mercury lamps in the visible and ultraviolet, and X-ray tubes. One recently developed, novel source of broad spectrum radiation is synchrotron radiation, which covers all of these spectral regions. Other radiation sources generate a narrow spectrum, but the emission wavelength can be tuned to cover a spectral range. Examples of these include klystrons in the microwave region and lasers across the infrared, visible, and ultraviolet region (though not all lasers have tunable wavelengths).

The detector employed to measure the radiation power will also depend on the wavelength range of interest. Most detectors are sensitive to a fairly broad spectral range and the sensor selected will often depend more on the sensitivity and noise requirements of a given measurement. Examples of detectors common in spectroscopy include heterodyne receivers in the microwave, bolometers in the millimeter-wave and infrared, mercury cadmium telluride and other cooled semiconductor detectors in the infrared, and photodiodes and photomultiplier tubes in the visible and ultraviolet.

If both the source and the detector cover a broad spectral region, then it is also necessary to introduce a means of resolving the wavelength of the radiation in order to determine the spectrum. Often a spectrograph is used to spatially separate the wavelengths of radiation so that the power at each wavelength can be measured independently. It is also common to employ interferometry to determine the spectrum—Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy is a widely used implementation of this technique.

Two other issues that must be considered in setting up an absorption spectroscopy experiment include the optics used to direct the radiation and the means of holding or containing the sample material (called a cuvette or cell). For most UV, visible, and NIR measurements the use of precision quartz cuvettes are necessary. In both cases, it is important to select materials that have relatively little absorption of their own in the wavelength range of interest. The absorption of other materials could interfere with or mask the absorption from the sample. For instance, in several wavelength ranges it is necessary to measure the sample under vacuum or in a noble gas environment because gases in the atmosphere have interfering absorption features.

مقاربات معينة

- Astronomical spectroscopy

- Cavity ring-down spectroscopy (CRDS)

- Laser absorption spectrometry (LAS)

- Mössbauer spectroscopy

- Photoacoustic spectroscopy

- Photoemission spectroscopy

- Photothermal optical microscopy

- Photothermal spectroscopy

- Reflectance spectroscopy

- Reflection-absorption infrared spectroscopy (RAIRS)

- Total absorption spectroscopy (TAS)

- Tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy (TDLAS)

- X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS)

- X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES)

انظر أيضاً

- ذرة

- طيف كهرومغناطيسي

- طيف إصدار ذري

- امتصاص (بصريات)

- Densitometry

- Fraunhofer lines

- HITRAN

- Lyman-alpha forest

- كثافة ضوئية

- Photoemission spectroscopy

- X-ray absorption spectroscopy

- مواد شفافة

- امتصاص الماء

الهامش

- ^ Kumar, Pranav (2018). Fundamentals and Techniques of Biophysics and Molecular biology. New Delhi: Pathfinder publication. p. 33. ISBN 978-93-80473-15-4.

- ^ James D. Ingle Jr. and Stanley R. Crouch, Spectrochemical Analysis, Prentice Hall, 1988, ISBN 0-13-826876-2

- ^ "Gaseous Pollutants – Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy". Archived from the original on 2012-10-23. Retrieved 2009-09-30.

- ^ Khalafinejad, S.; Essen, C. von; Hoeijmakers, H. J.; Zhou, G.; Klocová, T.; Schmitt, J. H. M. M.; Dreizler, S.; Lopez-Morales, M.; Husser, T.-O. (2017-02-01). "Exoplanetary atmospheric sodium revealed by orbital motion". Astronomy & Astrophysics (in الإنجليزية). 598: A131. arXiv:1610.01610. Bibcode:2017A&A...598A.131K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201629473. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 55263138.

- ^ de Wit, Julien; Seager, S. (19 December 2013). "Constraining Exoplanet Mass from Transmission Spectroscopy". Science. 342 (6165): 1473–1477. arXiv:1401.6181. Bibcode:2013Sci...342.1473D. doi:10.1126/science.1245450. PMID 24357312. S2CID 206552152.