معركة إنكرمان

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

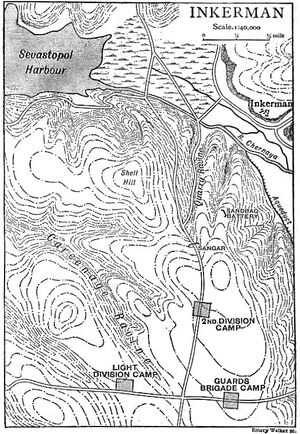

معركة إنكرمان Battle of Inkerman، كان قتال دار أثناء حرب القرم في 5 نوفمبر 1854 بين الجيوش البريطانية، الفرنسية، والعثمانية المتحالفة ضد الجيش الروسي الامبراطوري. كسرت المعركة إرادة الجيش الروسي على هزيمة الحلفاء في الميدان، وتلاها حصار سڤاستوپول. كثافة الضباب، أعاقت ترابط السيطرة والتحكم في جلا الجانبين. لذلك كان كل جندي يتصرف حسبما يرى في معظم الوقت، فلم تكن هناك أوامر بسبب الضباب. لذلك اشتهرت "بمعركة الجندي".[1]

تمهيد

The allied armies of Britain, France, Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire had landed on the west coast of Crimea on 14 September 1854, intending to capture the Russian naval base at Sevastopol.[2] The allied armies fought off and defeated the Russian Army at the Battle of Alma, forcing them to retreat in some confusion toward the River Kacha.[3] While the allies could have taken this opportunity to attack Sevastopol before Sevastopol could be put into a proper state of defence, the allied commanders, British general FitzRoy Somerset, 1st Baron Raglan and the French commander François Certain Canrobert could not agree on a plan of attack.[4]

Instead, they resolved to march around the city, and put Sevastopol under siege. Toward this end the allies marched to the southern coast of the Crimean peninsula and established a supply port at the city of Balaclava.[5] However, before the siege of Sevastopol began, the Russian commander Prince Menshikov evacuated Sevastopol with the major portion of his field army, leaving only a garrison to defend the city.[6] On 25 October 1854, a superior Russian force attacked the British base at Balaclava, and although the Russian attack was foiled before it could reach the base, the Russians were left holding a strong position north of the British line. Balaclava revealed the allied weakness; their siege lines were so long they did not have sufficient troops to man them. Realising this, Menshikov launched an attack across the Tchernaya River on 4 November 1854.[7]

المعركة

الهجوم

On 5 November 1854, the Russian 10th Division, under Lt. General F. I. Soymonov, launched a heavy attack on the allied right flank atop Home Hill east from the Russian position on Shell Hill.[8] The assault was made by two columns of 35,000 men and 134 field artillery guns[9] of the Russian 10th Division. When combined with other Russian forces in the area, the Russian attacking force would form a formidable army of some 42,000 men. The initial Russian assault was to be received by the British Second Division dug in on Home Hill with only 2,700 men and 12 guns. Both Russian columns moved in a flanking fashion east towards the British. They hoped to overwhelm this portion of the Allied army before reinforcements could arrive. The fog of the early morning hours aided the Russians by hiding their approach.[7] Not all the Russian troops could fit on the narrow 300-metre-wide heights of Shell Hill.[9] Accordingly, General Soymonov had followed Prince Alexander Menshikov's directive and deployed some of his force around the Careenage Ravine. Furthermore, on the night before the attack, Soymonov was ordered by General Peter A. Dannenberg to send part of his force north and east to the Inkerman Bridge to cover the crossing of Russian troop reinforcements under Lt. General P. Ya. Pavlov.[9] Thus, Soymonov could not effectively employ all of his troops in the attack.

When dawn broke, Soymonov attacked the British positions on Home Hill with 6,300 men from the Kolyvansky, Ekaterinburg and Tomsky regiments.[10] Soymonov also had a further 9,000 in reserve. The British had strong pickets and had ample warning of the Russian attack despite the early morning fog. The pickets, some of them at company strength, engaged the Russians as they moved to attack. The firing in the valley also gave warning to the rest of the Second Division, who rushed to their defensive positions. De Lacy Evans, commander of the British Second Division, had been injured in a fall from his horse so command of the Second Division was taken up by Major-General John Pennefather, a highly aggressive officer. Pennefather did not know that he was facing a superior Russian force. Thus he abandoned Evans' plan of falling back to draw the Russians within range of the British field artillery which was hidden behind Home Hill.[10] Instead, Pennefather ordered his 2,700 strong division to attack. When they did so, the Second Division faced some 15,300 Russian soldiers. Russian guns bombarded Home Hill, but there were no troops on the crest at this point.

اشتراك الفرقة الثانية، الروس في الوادي

هوم ريدج

اشتراك الفرقة الراقعة

دفاع القوات البريطانية والفرنسية عن هوم هيل

الذكرى

The battle popularised the use of the name Inkerman in placenames in Victorian England, including Inkerman Road in Kentish Town, London, Inkerman Road, St Albans, Inkerman Street in Preston, Inkerman Way in Knaphill, and Inkerman Court, House and Way in Denby Dale. There is an Inkerman Street in Mosman Mosman, New South Wales, Australia, in at the end of Countess St. There is also an Inkerman Street in St Kilda, Victoria, Australia, in between Balaclava Rd and Alma Rd. Inkerman, a locality in South Australia, was named in 1856. There is also an Inkerman, New Brunswick and an Inkerman, Ontario named after the battle.

On the popular and long running Granada Television soap opera Coronation Street, a nearby Inkerman Street has been mentioned on occasion.

On Operation Herrick in Afghanistan, there was a Forward Operating Base called FOB Inkerman.

The third company of the Grenadier Guards is known colloquially as the "Inkerman Company" for their part in the battle.

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

المصادر

- ^ Mackenzie (2021).

- ^ Figes (2010), p. 203.

- ^ Figes (2010), pp. 215–216.

- ^ Figes (2010), p. 222.

- ^ Figes (2010), p. 225.

- ^ Figes (2010), p. 241.

- ^ أ ب Figes (2010), p. 258.

- ^ Figes (2010), pp. 257–259.

- ^ أ ب ت Figes (2010), p. 257.

- ^ أ ب Figes (2010), p. 259.

قراءات إضافية

- Figes, Orlando (2010) The Crimean War: A History. New York: Picador Publishing, 2010

- Kinglake, A. W. (1863) Invasion of the Crimea. 8 vols. Edinburgh: Blackwood, 1863–1887