ملكية يوليو

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

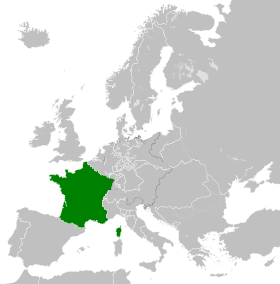

ملكية يوليو (فرنسية: Monarchie de Juillet) كانت ملكية دستورية ليبرالية في فرنسا في عهد لوي فيليپ الأول، بدءًا من ثورة يوليو الفرنسية عام 1830 وانتهاءًا ب ثورة 1848 الفرنسية. بدأ الأمر بالإطاحة بحكومة شارل العاشر و آل بوربون. أعلن لوي فيليپ، عضو في فرع أورليانز الأكثر ليبرالية في آل بوربون، نفسه باسم "ملك الفرنسيين" (" ملك فرنسا ") بدلاً من "ملك فرنسا"، مما يؤكد الأصول الشعبية لعهده. وعد الملك باتباع "" الوسط العادل "، أو وسط الطريق، متجنبًا التطرف سواء من أنصار شارل العاشر المحافظين أو المتطرفين من اليسار. سيطر الأثرياء البرجوازيين والعديد من المسؤولين السابقين في نپبليون على ملكية يوليو. واتبعت سياسات مقاومة، لا سيما تحت تأثير (1840-1848) من فرانسوا گزو. وقد عزز الملك الصداقة مع بريطانيا العظمى ورعى التوسع الاستعماري، ولا سيما غزو الجزائر. وبحلول عام 1848، قامت عام شهدت العديد من الدول الأوروبية ثورة، وانهارت شعبية الملك وأطيح به.

استعراض

بعد ثورة يوليو، استبدلت الألوان الثلاثة الفرنسية بـ العلم الأبيض لـ بوربون مرة أخرى. هذه كانت محاولة لربط الملكية الجديدة بتراث الثورة الفرنسية. |

دُفع لوي فيليپ إلى العرش من قبل تحالف بين شعب باريس ؛ الجمهوريون، الذين أقاموا المتاريس في العاصمة ؛ و الليبرالية البرجوازية. ومع ذلك، في نهاية عهده أُطيح بما يسمى ب "الملك المواطن" من خلال انتفاضات المواطنين المماثلة واستخدام المتاريس خلال ثورة فبراير 1848. وقد أسفر ذلك عن إعلان الجمهورية الثانية.[1]

الخلفية

Following the ouster of Napoléon Bonaparte in 1814, the Coalitions restored the Bourbon Dynasty to the French throne. The ensuing period, the Bourbon Restoration, was characterized by conservative reaction and the re-establishment of the Roman Catholic Church as one of the main powers in French politics. The relatively moderate Comte de Provence, brother of the deposed-and-executed Louis XVI, ruled as Louis XVIII from 1814 to 1824 and was succeeded by his more conservative younger brother, the former Comte d'Artois, ruling as Charles X from 1824. In May 1825 he had an elaborate coronation in Reims Cathedral which harkened back to the pre-revolutionary monarchy.

Despite the return of the House of Bourbon to power, France was much changed from the era of the ancien régime. The egalitarianism and liberalism of the revolutionaries remained an important force and the autocracy and hierarchy of the earlier era could not be fully restored. Economic changes, which had been underway long before the revolution, had progressed further during the years of turmoil and were firmly entrenched by 1815. These changes had seen power shift from the noble landowners to the urban merchants. The administrative reforms of Napoleon, such as the Napoleonic Code and efficient bureaucracy, also remained in place. These changes produced a unified central government that was fiscally sound and had much control over all areas of French life, a sharp difference from the complicated mix of feudal and absolutist traditions and institutions of pre-Revolutionary Bourbons.

Louis XVIII, for the most part, accepted that much had changed. However, he was pushed on his right by the Ultra-royalists, led by the comte de Villèle, who condemned the doctrinaires' attempt to reconcile the Revolution with the monarchy through a constitutional monarchy. Instead, the Chambre introuvable, elected in 1815, first banished all Conventionnels who had voted for Louis XVI's death and then passed similar reactionary laws. Louis XVIII was forced to dissolve this Chamber, dominated by the Ultras, in 1816, fearing a popular uprising. The liberals thus governed until the 1820 assassination of the Duke of Berry, nephew of the king and known supporter of the Ultras, which brought Villèle's Ultras back to power (vote of the Anti-Sacrilege Act in 1825, and of the loi sur le milliard des émigrés, 'Act on the émigrés' billions'). His brother Charles X, however, took a far more conservative approach. He attempted to compensate the aristocrats for what they had lost in the revolution, curbed the freedom of the press, and reasserted the power of the Church. In 1830 the discontent caused by these changes and Charles' authoritarian nomination of the Ultra prince de Polignac as minister culminated in an uprising in the streets of Paris, known as the 1830 July Revolution. Charles was forced to flee and Louis-Philippe d'Orléans, a member of the Orléans branch of the family, and son of Philippe Égalité who had voted the death of his cousin Louis XVI, ascended the throne. Louis-Philippe ruled, not as "King of France" but as "King of the French" (an evocative difference for contemporaries).

الفترة المبدئية (أغسطس 1830 – نوفمبر 1830)

التأسيس الرمزي لنظام جديد

On 7 August 1830, the 1814 Charter was revised. The preamble reviving the Ancien Régime was suppressed, and the King of France became the "King of the French", (also known as the "Citizen King") establishing the principle of national sovereignty over the principle of the divine right. The new Charter was a compromise between the Doctrinaires opposition to Charles X and the Republicans. Laws enforcing Catholicism and censorship were repealed and the revolutionary tricolor flag re-established.

Louis-Philippe pledged his oath to the 1830 Charter on 9 August setting up the beginnings of the July Monarchy. Two days later, the first cabinet was formed, gathering the constitutionalist opposition to Charles X, including Casimir Perier, the banker Jacques Laffitte, Count Molé, the duke of Broglie, François Guizot, etc. The new government's first aim was to restore public order, while at the same time appearing to acclaim the revolutionary forces which had just triumphed. Assisted by the people of Paris in overthrowing the Legitimists, the Orléanist bourgeoisie had to establish its new order.

Louis-Philippe decided on 13 August 1830 to adopt the arms of the House of Orléans as state symbols. Reviewing a parade of the Parisian National Guard on 29 August which acclaimed the adoption, he exclaimed to its leader, Lafayette: "This is worth more to me than coronation at Reims!".[2] The new regime then decided on 11 October that all people injured during the revolution (500 orphans, 500 widows and 3,850 people injured) would be given financial compensation and presented a draft law indemnifying them in the amount of 7 million francs, also creating a commemorative medal for the July Revolutionaries.

Ministers lost their honorifics of Monseigneur and Excellence and became simply Monsieur le ministre. The new king's older son, Ferdinand-Philippe, was given the title of Duke of Orléans and Prince Royal, while his daughters and his sister, Adélaïde d'Orléans, were named princesses of Orléans – and not of France, since there was no longer any "King of France" nor "House of France".

Unpopular laws passed during the Restoration were repealed, including the 1816 amnesty law which had banished the regicides – with the exception of article 4, concerning the Bonaparte family. The Church of Sainte-Geneviève was once again returned to its functions as a secular building, named the Panthéon. Various budget restrictions were imposed on the Catholic Church, while the 1825 Anti-Sacrilege Act which envisioned death penalties for sacrilege was repealed.

اضطراب دائم

Civil unrest continued for three months, supported by the left-wing press. Louis-Philippe's government was not able to put an end to it, mostly because the National Guard was headed by one of the Republican leaders, the Marquis de La Fayette, who advocated a "popular throne surrounded by Republican institutions". The Republicans then gathered themselves in popular clubs, in the tradition established by the 1789 Revolution. Some of those were fronts for secret societies (for example, the Blanquist Société des Amis du Peuple), which sought political and social reforms, or the execution of Charles X's ministers (Jules de Polignac, Jean de Chantelauze, the Count de Peyronnet and the Martial de Guernon-Ranville). Strikes and demonstrations were permanent.[3]

In order to stabilize the economy and finally secure public order, in the autumn of 1830 the government had the Assembly vote a credit of 5 million francs to subsidize public works, mostly roads. Then, to prevent bankruptcies and the increase of unemployment, especially in Paris, the government issued a guarantee for firms encountering difficulties, granting them 60 million francs. These subsidies mainly went into the pockets of big entrepreneurs aligned with the new regime, such as the printer Firmin Didot.

The death of the Prince of Condé on 27 August 1830, who was found hanged, caused the first scandal of the July Monarchy. Without proof, the Legitimists quickly accused Louis-Philippe and the Queen Marie-Amélie of having assassinated the ultra-royalist Prince, with the alleged motive of allowing their son, the Duke of Aumale, to get his hands on his fortune. It is however commonly acceptedقالب:Weasel word that the Prince died as a result of sex games with his mistress, the Baroness de Feuchères.[citation needed]

تطهير المطالبين بالشرعية

Meanwhile, the government expelled from the administration all Legitimist supporters who refused to pledge allegiance to the new regime, leading to the return to political affairs of most of the personnel of the First Empire, who had themselves been expelled during the Second Restoration. This renewal of political and administrative staff was humorously illustrated by a vaudeville of Jean-François Bayard.[4] The Minister of the Interior, Guizot, re-appointed the entire prefectoral administration and the mayors of large cities. The Minister of Justice, Dupont de l'Eure, assisted by his secretary general, Mérilhou, dismissed most of the public prosecutors. In the Army, the General de Bourmont, a follower of Charles X who was commanding the invasion of Algeria, was replaced by Bertrand Clauzel. Generals, ambassadors, plenipotentiary ministers and half of the Conseil d'État were replaced. In the Chamber of Deputies, a quarter of the seats (119) were submitted to a new election in October, leading to the defeat of the Legitimists.

In sociological terms, however, this renewal of political figures did not mark any great change of elites. The old land-owners, civil servants and liberal professions continued to dominate the state of affairs, leading the historian David H. Pinkney to deny any claim of a "new regime of a grande bourgeoisie".[5]

The "Resistance" and the "Movement"

Although some voices began to push for the closure of the Republican clubs, which fomented revolutionary agitation, the Minister of Justice, Dupont de l'Eure, and the Parisian public prosecutor, Bernard, both Republicans, refused to prosecute revolutionary associations (the French law prohibited meetings of more than 20 persons).

However, on 25 September 1830, the Minister of Interior Guizot responded to a deputy's question on the subject by stigmatizing the "revolutionary state", which he conflated with chaos, to which he opposed the Glorious Revolution in England in 1688.[6]

Two political currents thereafter made their appearance, and would structure political life under the July Monarchy: the Movement Party and the Resistance Party. The first was reformist and in favor of support to the nationalists who were trying, all over of Europe, to shake the grip of the various Empires in order to create nation-states. Its mouthpiece was Le National. The second was conservative and supported peace with European monarchs, and had as mouthpiece Le Journal des débats.

The trial of Charles X's ministers, arrested in August 1830 while they were fleeing, became the major political issue. The left demanded their heads, but this was opposed by Louis-Philippe, who feared a spiral of violence and the renewal of revolutionary Terror. Thus, on 27 September 1830 the Chamber of Deputies passed a resolution charging the former ministers, but at the same time, in an address to King Louis-Philippe on 8 October, invited him to present a draft law repealing the death penalty, at least for political crimes. This in turn provoked popular discontent on 17 and 18 October, with the masses marching on the Château de Vincennes where the former ministers were detained.

Following these riots, Interior Minister Guizot requested the resignation of the Prefect of the Seine, Odilon Barrot, who had criticized the parliamentarians' address to the king. Supported by Victor de Broglie, Guizot considered that an important civil servant could not criticize an act of the Chamber of Deputies, particularly when it had been approved by the King and his government. Dupont de l'Eure took Barrot's side, threatening to resign if the king disavowed him. The banker Laffitte, one of the main figures of the Parti du mouvement, thereupon put himself forward to coordinate the ministers with the title of "President of the Council". This immediately led Broglie and Guizot, of the Parti de l'Ordre, to resign, followed by Casimir Perier, André Dupin, the Count Molé and Joseph-Dominique Louis. Confronted to the Parti de l'Ordre's defeat, Louis-Philippe decided to put Laffitte to trial, hoping that the exercise of power would discredit him. He thus called him to form a new government on 2 November 1830.

حكومة لافيت (2 نوفمبر 1830 – 13 مارس 1831)

بالرغم من أن لوي فيليپ اختلف بشدة مع المصرفي لافيت وتعهد سراً لدوق برولي بأنه لن يدعمه على الإطلاق، فقد خُدع رئيس المجلس الجديد ليثق بملكه.

The trial of Charles X's former ministers took place from 15 to 21 December 1830 before the Chamber of Peers, surrounded by rioters demanding their death. They were finally sentenced to life detention, accompanied by civil death for Polignac. La Fayette's National Guard maintained public order in Paris, affirming itself as the bourgeois watchdog of the new regime, while the new Interior Minister, Camille de Montalivet, kept the former ministers safe by detaining them in the Château de Vincennes.

But by demonstrating the National Guard's importance, La Fayette had made his position delicate, and he was quickly forced to resign. This led to the Minister of Justice Dupont de l'Eure's resignation. In order to avoid exclusive dependence on the National Guard, the "Citizen King" charged Marshal Soult, the new Minister of War, with reorganizing the Army. In February 1831, Soult presented his project, aiming to increase the military's effectiveness. Among other reforms, the project included the 9 March 1831 law creating the Foreign Legion.

In the meantime, the government enacted various reforms demanded by the Parti du Mouvement, which had been set out in the Charter (art. 69). The 21 March 1831 law on municipal councils reestablished the principle of election and enlarged the electorate (founded on census suffrage) which was thus increased tenfold in comparison with the legislative elections (approximately 2 to 3 million electors from a total population of 32,6 million). The 22 March 1831 law re-organized the National Guard; the 19 April 1831 law, voted after two months of debate in Parliament and promulgated after Laffitte's downfall, decreased the electoral income level from 300 to 200 francs and the level for eligibility from 1,000 to 500 francs. The number of voters thereby increased from less than 100,000 to 166,000: one Frenchman in 170 possessed the right to vote, and the number of constituencies rose from 430 to 459.

شغب فبراير 1831

Despite these reforms, which targeted the bourgeoisie rather than the people, Paris was once again rocked by riots on 14 and 15 February 1831, leading to Laffitte's downfall. The immediate cause of the riots was a funeral service organized by the Legitimists at Saint-Germains l'Auxerrois Church in memory of the ultra-royalist Duke of Berry, assassinated in 1820. The commemoration turned into a political demonstration in favor of Henri, Count of Chambord, Legitimist pretender to the throne. Seeing in this celebration an intolerable provocation, the Republican rioters ransacked the church two days in a row, before turning on other churches. The revolutionary movement spread to other cities.

Confronted with renewed unrest, the government abstained from any strong repression. The prefect of the Seine Odilon Barrot, the prefect of police Jean-Jacques Baude, and the new commandant of the National Guard, General Georges Mouton, remained passive, triggering Guizot's indignation, as well as the Republican Armand Carrel's criticisms against the demagogy of the government. Far from suppressing the crowds, the government had the Archbishop of Paris Mgr de Quélen arrested, as well as charging the friar of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois and other priests, along with some other monarchists, with having provoked the masses.

In a gesture of appeasement, Laffitte, supported by the Prince Royal Ferdinand-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, proposed to the king that he remove the fleur-de-lys, symbol of the Ancien Régime, from the state seal. With obvious displeasure, Louis-Philippe finally signed the 16 February 1831 ordinance substituting for the arms of the House of Orléans a shield with an open book, on which could be read "Charte de 1830". The fleur-de-lys, was also removed from public buildings, etc. This new defeat of the king sealed Laffitte's fate.

On 19 February 1831, Guizot verbally attacked Laffitte in the Chamber of Deputies, daring him to dissolve the Chamber and present himself before the electors. Laffitte accepted, but the king, who was the only one entitled to dissolve the Chamber, preferred to wait a few days more. In the meanwhile, the Prefect of the Seine Odilon Barrot was replaced by Taillepied de Bondy at Montalivet's request, and the prefect of police Jean-Jacques Baude by Vivien de Goubert. To make matters worse, in this insurrectionary climate, the economic situation was fairly bad.

Louis-Philippe finally tricked Laffitte into resigning by having his Minister of Foreign Affairs, Horace Sébastiani, pass him a note written by the French ambassador to Vienna, Marshal Maison, and which had arrived in Paris on 4 March 1831, which announced an imminent Austrian intervention in Italy. Learning of this note in Le Moniteur of 8 March, Laffitte requested an immediate explanations from Sébastiani, who replied that he had followed royal orders. After a meeting with the king, Laffitte submitted to the Council of Ministers a belligerent program, and was subsequently disavowed, forcing him to resign. Most of his ministers had already negotiated their positions in the forthcoming government.

حكومة كاسيمير پرييه (13 مارس 1831 – 16 مايو 1832)

Having succeeded in outdoing the Parti du Mouvement, the "Citizen King" called to power the Parti de la Résistance. However, Louis-Philippe was not really much more comfortable with one side than with the other, being closer to the center. Furthermore, he felt no sympathy for its leader, the banker Casimir Pierre Périer, who replaced Laffitte on 13 March 1831 as head of the government. His aim was more to re-establish order in the country, letting the Parti de la Résistance assume responsibility for unpopular measures.

Périer, however, managed to impose his conditions on the king, including the pre-eminence of the President of the Council over other ministers, and his right to call cabinet councils outside of the actual presence of the king. Furthermore, Casimir Perier secured agreement that the liberal Prince Royal, Ferdinand-Philippe d'Orléans, would cease to participate to the Council of Ministers. Despite this, Perier valued the king's prestige, calling on him, on 21 September 1831, to move from his family residence, the Palais-Royal, to the royal palace, the Tuileries.

The banker Périer established the new government's principles on 18 March 1831: ministerial solidarity and the authority of the government over the administration: "the principle of the July Revolution... is not insurrection... it is resistance to the aggression the power"[7] and, internationally, "a pacific attitude and the respect of the non-intervention principle". The vast majority of the Chamber applauded the new government and granted him a comfortable majority. Périer harnessed the support of the cabinet through oaths of solidarity and strict discipline for dissenters. He excluded reformers from official discourse, and abandoned the regime's unofficial policy of mediating in labor disputes in favor of a strict laissez-faire policy that favored employers.

الاضطرابات المدنية (ثورة كانوت) والقمع

On 14 March 1831, on the initiative of a patriotic society created by the mayor of Metz, Jean-Baptiste Bouchotte, the opposition's press launched a campaign to gather funds to create a national association aimed at struggling against any Bourbon Restoration and the risks of foreign invasion. All the major figures of the Republican Left (La Fayette, Dupont de l'Eure, Jean Maximilien Lamarque, Odilon Barrot, etc.) supported it. Local committees were created all over France, leading the new president of the Council, Casimir Périer, to issue a circular prohibiting civil servants from membership of this association, which he accused of challenging the state itself by implicitly accusing it of not fulfilling its proper duties.

In the beginning of April 1831, the government took some unpopular measures, forcing several important personalities to resign: Odilon Barrot was dismissed from the Council of State, General Lamarque's military command suppressed, Bouchotte and the Marquis de Laborde forced to resign. When on 15 April 1831 the Cour d'assises acquitted several young Republicans (Godefroy Cavaignac, Joseph Guinard and Audry de Puyraveau's son), mostly officers of the National Guard who had been arrested during the December 1830 troubles following the trial of Charles X's ministers, new riots acclaimed the news on 15–16 April. But Périer, implementing the 10 April 1831 law outlawing public meetings, used the military as well as the National Guard to dissolve the crowds. In May, the government used fire hoses as crowd control techniques for the first time.

Another riot, started on the Rue Saint-Denis on 14 June 1831, degenerated into an open battle against the National Guard, assisted by the Dragoons and the infantry. The riots continued on 15 and 16 June.

The major unrest, however, took place in Lyon with the Canuts Revolt, started on 21 November 1831, and during which parts of the National Guard took the demonstrators' side. In two days, the Canuts took control of the city and expelled General Roguet and the mayor Victor Prunelle. On 25 November Casimir Périer announced to the Chamber of Deputies that Marshal Soult, assisted by the Prince Royal, would immediately march on Lyon with 20,000 men. They entered the city on 3 December re-establishing order without any bloodshed.

Civil unrest, however, continued, and not only in Paris. On 11 March 1832, sedition exploded in Grenoble during the carnival. The prefect had canceled the festivities after a grotesque mask of Louis-Philippe had been displayed, leading to popular demonstrations. The prefect then tried to have the National Guard disperse the crowd, but the latter refused to go, forcing him to call on the army. The 35th regiment of infantry (infanterie de ligne) obeyed the orders, but this in turn led the population to demand their expulsion from the city. This was done on 15 March and the 35th regiment was replaced by the 6th regiment, from Lyon. When Casimir Perier learnt the news, he dissolved the National Guard of Grenoble and immediately recalled the 35th regiment to the city.

Beside this continuing unrest, in every province, Dauphiné, Picardy, in Carcassonne, Alsace, etc., various Republican conspiracies threatened the government (conspiracy of the Tours de Notre-Dame in January 1832, of the rue des Prouvaires in February 1832, etc.) Even the trials of suspects were seized on by the Republicans as an opportunity to address the people: at the trial of the Blanquist Société des Amis du peuple in January 1832, Raspail harshly criticized the king while Auguste Blanqui gave free vein to his socialist ideas. All of the accused denounced the government's tyranny, the incredibly high cost of Louis-Philippe's civil list, police persecutions, etc. The omnipresence of the French police, organized during the French First Empire by Fouché, was depicted by the Legitimist writer Balzac in Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes. The strength of the opposition led the Prince Royal to shift his view somewhat further to the right.

Legislative elections of 1831

In the second half of May 1831, Louis-Philippe, accompanied by Marshal Soult, started an official visit to Normandy and Picardy, where he was well received. From 6 June to 1 July 1831, he traveled in the east, where there was stronger Republican and Bonapartist activity, along with his two elder sons, the Prince Royal and the Duke of Nemours, as well as with the comte d'Argout. The king stopped in Meaux, Château-Thierry, Châlons-sur-Marne (renamed Châlons-en-Champagne in 1998), Valmy, Verdun and Metz. There, in the name of the municipal council, the mayor made a very political speech in which he expressed the wish to have peerages abolished, adding that France should intervene in Poland to assist the November Uprising against Russia. Louis-Philippe flatly rejected all of these aspirations, stating that the municipal councils and the National Guard had no standing in such matters. The king continued his visit to Nancy, Lunéville, Strasbourg, Colmar, Mulhouse, Besançon and Troyes, and his visits were, on the whole, occasions to re-affirm his authority.

Louis-Philippe decided in the Château de Saint-Cloud, on 31 May 1831, to dissolve the Chamber of Deputies, fixing legislative elections for 5 July 1831. However, he signed another ordinance on 23 June in Colmar in order to have the elections put back to 23 July 1831, so as to avoid the risk of Republican agitation during the commemorations of the July Revolution. The general election of 1831 took place without incident, according to the new electoral law of 19 April 1831. However, the results disappointed the king and the president of the Council, Périer: more than half of the outgoing deputies were re-elected, and their political positions were unknown. The Legitimists obtained 104 seats, the Orléanist Liberals 282 and the Republicans 73.

On 23 July 1831, the king set out Casimir Périer's program in the speech from the Throne: strict application of the Charter at home and strict defense of the interests of France and its independence abroad.

The deputies in the chamber then voted for their President, electing Baron Girod de l'Ain, the government's candidate, on the second round. He gained 181 votes to the banker Laffitte's 176. But Dupont de l'Eure gained the first vice presidency with 182 voices out of a total of 344, defeating the government's candidate, André Dupin, who had only 153 votes. Casimir Périer, who considered that his parliamentary majority was not strong enough, decided to resign.

Louis-Philippe thereafter turned towards Odilon Barrot, who refused to assume governmental responsibilities, pointing out that he had only a hundred deputies in the Chamber. However, during the 2 and 2 August 1831 elections of questeurs and secretaries, the Chamber elected mostly government candidates such as André Dupin and Benjamin Delessert, who obtained a strong majority against a far-left candidate, Eusèbe de Salverte. Finally, William I of the Netherlands's decision to invade Belgium – the Belgian Revolution had taken place the preceding year – on 2 August 1831, constrained Casimir Perier to remain in power in order to respond to the Belgians' request for help.

During the parliamentary debates concerning France's imminent intervention in Belgium, several deputies, led by Baron Bignon, unsuccessfully requested similar intervention to support Polish independence. However, at the domestic level, Casimir Perier decided to back down before the dominant opposition, and satisfied an old demand of the Left by abolishing hereditary peerages. Finally, the 2 March 1832 law on Louis-Philippe's civil list fixed it at 12 million francs a year, and one million for the Prince Royal, the Duke of Orléans. The 28 April 1832 law, named after the Justice Minister Félix Barthe, reformed the 1810 Penal Code and the Code d'instruction criminelle.

The 1832 cholera epidemic

The cholera pandemic that originated in India in 1815 reached Paris around 20 March 1832 and killed more than 13,000 people in April. The pandemic would last until September 1832, killing in total 100,000 in France, with 20,000 in Paris alone.[8] The disease, the origins of which were unknown at the time, provoked a popular panic. The people of Paris suspected poisoners, while scavengers and beggars revolted against the authoritarian measures of public health.

According to the 20th-century historian and philosopher Michel Foucault, the cholera outbreak was first fought by what he called "social medicine", which focused on flux, circulation of air, location of cemeteries, etc. All of these concerns, born of the miasma theory of disease, were thus concerned with urbanist concerns of the management of populations.

Cholera also struck the royal princess Madame Adélaïde, as well as d'Argout and Guizot. Casimir Périer, who on 1 April 1832 visited the patients at the Hôtel-Dieu with the Prince Royal, contracted the disease. He resigned his ministerial activities before dying of cholera on 16 May 1832.

استجماع النظام (1832–1835)

King Louis-Philippe did not regret the departure of Casimir Périer from the political scene, as he complained that Périer took all the credit for the government's policy successes, while he himself had to assume all the criticism for its failures.[9] The "Citizen King" was therefore not in any hurry to find a new President of the Council, all the more since the Parliament was in recess and that the troubled situation demanded swift and energetic measures.

Indeed, the regime was being attacked on all sides. The Legitimist Duchess of Berry attempted an uprising in spring 1832 in Provence and Vendée, a stronghold of the ultra-royalists, while the Republicans headed an insurrection in Paris on 5 June 1832, on the occasion of the funeral of one of their leaders, General Lamarque, also struck dead by the cholera. General Mouton crushed the rebellion. (Victor Hugo later described the scene in his 1862 novel Les Misérables.)

This double victory, over both Legitimists and the Republicans, was a success for the July Monarchy regime.[10] Furthermore, the death of the Duke of Reichstadt (Napoléon II) on 22 July 1832, in Vienna, marked another setback for the Bonapartist opposition.

Finally, Louis-Philippe married his elder daughter, Louise d'Orléans, to the newly-appointed King of the Belgians, Leopold I, on the anniversary of the establishment of the July Monarchy (9 August). Since the Archbishop of Paris, Quélen (a Legitimist), refused to celebrate this mixed marriage between a Catholic and a Lutheran, the wedding took place in the Château de Compiègne. This royal alliance strengthened Louis-Philippe's position abroad.

First Soult government

Louis-Philippe called a trusted man, Marshal Soult, to the Presidency of the Council in October 1832. Soult was supported by a triumvirate composed of the main politicians of that time: Adolphe Thiers, the duc de Broglie and François Guizot. The conservative Journal des débats spoke of a "coalition of all talents",[11] while the King of the French would eventually speak, with obvious disappointment, of a "Casimir Périer in three persons". In a circular addressed to the high civil-servants and military officers, the new President of the Council, Soult, stated that he would explicitly follow the policies of Périer ("order at home", "peace abroad") and denounced both the Legitimist right-wing opposition and the Republican left-wing opposition.

The new Minister of Interior, Adolphe Thiers, had his first success on 7 November 1832 with the arrest in Nantes of the rebellious Duchess of Berry, who was detained in the citadel of Blaye. The duchess was then expelled to Palermo in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies on 8 June 1833.

The opening of the parliamentary session on 19 November 1832, was a success for the regime. The governmental candidate, André Dupin, was easily elected on the first round as President of the Chamber, with 234 votes against 136 for the candidate of the opposition, Jacques Laffitte.

In Belgium, Marshal Gérard assisted the young Belgian monarchy with 70,000 men, taking back the citadel of Antwerp, which capitulated on 23 December 1832.

Strengthened by these recent successes, Louis-Philippe initiated two visits to the provinces, first into the north to meet with the victorious Marshal Gérard and his men, and then into Normandy, where Legitimist troubles continued, from August to September 1833. In order to conciliate public opinion, the members of the new government took some popular measures, such as a program of public works, leading to the completion of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, and the re-establishment, on 21 June 1833, of Napoleon I's statue on the Colonne Vendôme. The Minister of Public Instruction and Cults, François Guizot, had the famous law on primary education passed in June 1833, leading to the creation of an elementary school in each commune.

Finally, a ministerial change was enacted after the Duke de Broglie's resignation on 1 April 1834. Broglie had found himself in a minority in the Chamber concerning the ratification of a treaty signed with the United States in 1831. This was a source of satisfaction for the king, as it removed from the triumvirate the individual he disliked the most.

تمرد أبريل 1834

The ministerial change coincided with the return of violent unrest in various cities of France. At the end of February 1834, a new law that subjected the activities of town criers to public authorization led to several days of confrontations with the police. Furthermore, the 10 April 1834 law, primarily aimed against the Republican Society of the Rights of Man (Société des Droits de l'Homme), envisioned a crack-down on non-authorized associations. On 9 April 1834, when the Chamber of Peers was to vote on the law, the Second Canut Revolt exploded in Lyon. The Minister of the Interior, Adolphe Thiers, decided to abandon the city to the insurgents, taking it back on 13 April with casualties of 100 to 200 dead on both sides.

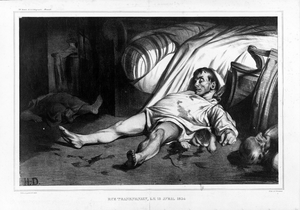

The Republicans attempted to spread the insurrection to other cities, but failed in Marseille, Vienne, Poitiers and Châlons-sur-Marne. More serious Republican threats developed in Grenoble and especially in Saint-Étienne on 11 April, but finally public order was restored. The greater danger to the regime was, as often, in Paris. Expecting trouble, Thiers had concentrated 40,000 men there, who were visited by the king on 10 April. Furthermore, Thiers had made "preventive arrests" of 150 principal leaders of the Society of the Rights of Man and outlawed its mouthpiece, La Tribune des départements. Despite these measures, barricades were set up in the evening of 13 April 1834, leading to harsh repression, including a massacre of all the inhabitants (men, women, children and old people) of a house from where a shot had been fired. This incident was immortalized in a lithograph by Honoré Daumier.

To express their support for the monarchy, both Chambers gathered in the Palace of the Tuileries on 14 April. In a gesture of appeasement, Louis-Philippe canceled his feast-day celebration on 1 May, and publicly announced that the sums that were to have been used for these festivities would be dedicated to the orphans, widows and injured. In the same time, he ordered Marshal Soult to publicize these events widely across France (the provinces being more conservative than Paris), to convince them of the "necessary increase in the Army".[12]

More than 2,000 arrests were made following the riots, in particular in Paris and Lyon. The cases were referred to the Chamber of Peers, which, in accordance with art. 28 of the Charter of 1830, dealt with cases of conspiracy against state security (فرنسية: attentat contre la sûreté de l'État). The Republican movement was decapitated, so much that even the funeral of La Fayette (died 20 May 1834), passed with little incident. As early as 13 May the Chamber of Deputies voted a credit of 14 million in order to increase the army to 360,000 men. Two days later, they also adopted a very repressive law on detention and use of military weapons.

Legislative elections of 1834

Louis-Philippe decided to seize the opportunity of dissolving the Chamber and organizing new elections, which were held on 21 June 1834. However, the results were not as favorable to him as expected: although the Republicans were almost eliminated, the Opposition retained around 150 seats (approximately 30 Legitimists, the rest being followers of Odilon Barrot, who was an Orléanist supporter of the regime, but headed the Parti du mouvement). Furthermore, in the ranks of the majority itself, composed of about 300 deputies, a new faction, the Tiers-Parti, led by André Dupin, could on some occasions defect from the majority and give its votes to the Left. On 31 July the new Chamber re-elected Dupin as President of the Chamber with 247 votes against 33 for Jacques Laffitte and 24 for Pierre-Paul Royer-Collard. Furthermore, a large majority (256 against 39) voted an ambiguous address to the king which, although polite, did not abstain from criticizing him. The latter immediately decided, on 16 August 1834, to prorogue Parliament until the end of the year.

Short-lived governments (July 1834 – February 1835)

Thiers and Guizot, who dominated the triumvirate, decided to get rid of Marshal Soult, who was appreciated by the king for his compliant attitude. Seizing the opportunity of an incident concerning the French possessions in Algeria, they pushed Soult to resign on 18 July 1834. He was replaced by Marshal Gérard, with the other ministers remaining in place. Gérard however, was forced to resign in turn, on 29 October 1834, over the question of an amnesty for the 2,000 prisoners detained in April. Louis-Philippe, the Doctrinaires (including Guizot and Thiers) and the core of the government opposed the amnesty, but the Tiers-Parti managed to convince Gérard to announce it, underscoring the logistical difficulties in organizing such a large trial before the Chamber of Peers.

Gérard's resignation opened up a four-month ministerial crisis, until Louis-Philippe finally assembled a government entirely from the Tiers-Parti. However, after André Dupin's refusal to assume its presidency, the king made the mistake of calling, on 10 November 1834, a figure from the First Empire, the duc de Bassano, to head his government. The latter, crippled with debts, became the object of public ridicule after his creditors decided to seize his ministerial salary. Alarmed, all the ministers decided to resign, three days later, without even advising Bassano, whose government became known as the "Three Days Ministry". On 18 November 1834, Louis-Philippe called Marshal Mortier, Duke of Trévise, to the Presidency, and the latter formed exactly the same government as Bassano. This crisis made the Tiers-Parti ridiculous while the Doctrinaires triumphed.

On 1 December 1834, Mortier's government decided to submit a motion of confidence to the Parliament, obtaining a clear majority (184 votes to 117). Despite this, Mortier had to resign two months later, on 20 February 1835, officially for health reasons. The opposition had denounced a government without a leader, accusing Mortier of being Louis-Philippe's puppet. The same phrase that Thiers had spoken in opposition to Charles X, "the king reigns but does not rule" (le roi règne mais ne gouverne pas), was now addressed to the "Citizen King".

التطور نحو البرلمانية (1835-1840)

The polemics which led to Marshal Mortier's resignation, fueled by monarchists such as Baron Massias and the Count of Roederer, all turned around the question of parliamentary prerogative. On the one hand, Louis-Philippe wanted to be able to follow his own policy, in particular in "reserved domains" such as military affairs or diplomacy. As the head of state, he also wanted to be able to lead the government, if need be by bypassing the President of the Council. On the other hand, a number of the deputies stated that the ministers needed a leader commanding a parliamentary majority, and thus wanted to continue the evolution towards parliamentarism which had only been sketched out in the Charter of 1830. The Charter did not include any mechanism for the political accountability of ministers towards the Chamber (confidence motions or for censorship motions). Furthermore, the function of the President of the Council itself was not even set out in the Charter.

The Broglie ministry (March 1835 – February 1836)

In this context, the deputies decided to support Victor de Broglie as head of the government, mainly because he was the king's least preferred choice, as Louis-Philippe disliked both his anglophilia and his independence. After a three-week ministerial crisis, during which the "Citizen King" successively called on Count Molé, André Dupin, Marshal Soult, General Sébastiani and Gérard, he was finally forced to rely on the duc de Broglie and to accept his conditions, which were close to those imposed before by Casimir Périer.

As in the first Soult government, the new cabinet rested on the triumvirate of Broglie (Foreign affairs), Guizot (Public instruction), and Thiers (Interior). Broglie's first act was to take a personal revenge on the Chamber by having it ratify (by 289 votes against 137) the 4 July 1831 treaty with the United States, something which the deputies had refused him in 1834. He also obtained a large majority on the debate over the secret funds, which worked as an unofficial motion of confidence (256 voices against 129).

Trial of the April insurgents

Broglie's most important task was the trial of the April insurgents, which began on 5 May 1835 before the Chamber of Peers. The Peers finally convicted only 164 detainees on the 2,000 prisoners, of whom 43 were judged in absentia. Those defendants who were present for their trial introduced a great many procedural delays, and attempted by all means to transform the trial into a platform for Republicanism. On 12 July 1835, some of them, including the main leaders of the Parisian insurrection, escaped from the Prison of Sainte-Pélagie through a tunnel. The Court of Peers delivered its sentence on the insurgents of Lyon on 13 August 1835, and on the other defendants in December 1835 and January 1836. The sentences were rather mild: a few condemnations to deportation, many short prison sentences and some acquittals.

The Fieschi attentat (28 يوليو 1835)

حكومتا موليه (سبتمبر 1836 – مارس 1839)

حكومة سولت الثانية (May 1839 – February 1840)

حكومة تيير الثانية (March – October 1840)

عودة رفات ناپليون

في حين أن تيير فضل البرجوازية المحافظة، فقد حرص أيضًا على إرضاء تعطش اليسار إلى المجد. في 12 مايو 1840، أعلن وزير الداخلية شارل دى رموسا، للنواب أن الملك قرر أن رفات ناپليون ستنقل إلى الأنڤاليد. وبموافقة الحكومة البريطانية، أبحر أمير جونڤيل إلى سانت هيلينا على الفرقاطة La Belle Poule لاستعادته. ضرب هذا الإعلان على الفور وترا حساساً في الرأي العام، الذي اجتاح الحماسة الوطنية.

ورأى تيير في هذا الفعل إكمالًا ناجحًا لإعادة تأهيل الثورة والإمبراطورية، وهو ما حاوله في كتابه "تاريخ الثورة الفرنسية" و "تاريخ القنصلية والإمبراطورية"، بينما كان لوي فيليپ متردداً، ويهدف إلى الحصول على لمسة من المجد الإمبراطوري، تماماً كما استولى على مجد النظام الملكي الشرعي في قلعة ڤرساي.

قرر الأمير لوي ناپليون اغتنام الفرصة للرسو في بولوني-سور-مير في 6 أغسطس 1840، وذلك بهدف حشد فوج المشاة الثاني والأربعين (فوج المقدمة) بجانب بعض المتواطئين بما في ذلك أحد أصدقاء ناپليون في سانت هيلينا، الجنرال مونتولون. وبالرغم من أن الجنرال مونتولون كان في الواقع عميلاً مزدوجاً تستخدمه الحكومة الفرنسية للتجسس في لندن على لوي ناپليون. خدع مونتولون تيير بالسماح له بالاعتقاد بأن العملية ستتم في ميتز. ومع ذلك، كانت عملية بونابرت فاشلة تمامًا، واُعتقل مع رجاله في قلعة هام في بيكاري. عُقدت محاكمتهم أمام قاعة النبلاء في الفترة من 28 سبتمبر 1840 إلى 6 أكتوبر 1840، دون مبالاة من العامة. حيث كان جُل انتباه الجمهور على محاكمة ماري لافارج التي امتثلت أمام محكمة الجنايات لـ تول، المتهمة بقتل زوجها عن طريق السم. حيث كان المحامي الشرعي الشهير پيير أنطوان بيرييه يُدافع عنها. وقد حُكم على بونابرت بـ السجن المؤبد، بأغلبية 152 صوتًا (مقابل 160 امتناعًا عن التصويت ، من إجمالي 312 من أقرانه). "نحن لا نقتل المجانين ، حسناً! لكننا نسجنهم،[13] ذلك ما أعلنته صحيفة المرافعات في هذه الفترة من المناقشات المكثفة بشأن قتل الأبوين و الأمراض العقلية وإصلاح قانون العقوبات[14]

استعمار الجزائر

احتلال الجزائر، بدأ في الأيام الأخيرة من استعادة البوربون، وقد واجهه عبد القادر حالاً بالغارات، ومعاقبة مارشل ڤالي و دوق اورليانز بإرسالهم إلى "Portes de Fer" في خريف عام 1839، والذي انتهك شروط معاهدة تفنة 1837 بين الجنرال بوجود وعبد القادر. دفع تيير لصالح استعمار المناطق الداخلية من البلاد، حتى أطراف الصحراء. كما أقنع الملك، الذي رأى في الجزائر مسرحاً مثالياً لابنه من أجل أن يهيمن آل أورليان على المجد، وأقنعه بإرسال الجنرال بوجود أولًا لـ الحاكم العام للجزائر. وقد عُين بوجود رسميًا في 29 ديسمبر 1840، بعد أيام قليلة من سقوط تيير، الذي قام بعملية قمع شديدة ضد السكان الأصليين.

شئون شرق أوسطية، كذريعة لسقوط تيير

دعم تيير محمد علي باشا، باشا مصر، وذلك ابتغاء إنشاء إمبراطورية عربية واسعة من مصر إلى سوريا. كما حاول التوسط من أجل الحصول على توقيع الاتفاقية مع الدولة العثمانية، دون علم القوى الأوروبية الأربع الأخرى (بريطانيا والنمسا وبروسيا وروسيا). بالرغم من علمه بهذه المفاوضات، فإن وزير الخارجية البريطاني، اللورد پالمرستون، تفاوض على معاهدة بين القوى الأربع لحل "القضيةالشرقية" بشكلٍ سريع. عندما كُشف عن معاهدة لندن بتاريخ 15 يوليو 1840، أحدث ذلك انفجار الغضب الوطني: طُردت فرنسا من منطقة تمارس فيها نفوذها تقليديًا، في حين أن بروسيا، التي لم تكن لها مصلحة فيها كانت مرتبطة بالمعاهدة. بالرغم من تظاهر لوي فيليپ بالانضمام إلى الاحتجاجات العامة، إلا أنه كان يعلم أنه يمكنه الاستفادة من الموقف للتخلص من تيير. وقد قوّض الأخر المشاعر الوطنية بإصداره مرسوم في 29 يوليو 1840، بتعبئة جزئية وببدء الأعمال الخاصة بتحصينات پاريس في 13 سبتمبر 1840. لكن فرنسا ظلت مكتوفة الأيدي عندما قصفت البحرية البريطانية في 2 أكتوبر 1840 بيروت. ومن ثم قام السلطان بفصل محمد علي على الفور من منصب نائب الملك. وبعد مفاوضات طويلة بين الملك وتيير، تم التوصل إلى نسوية في 7 أكتوبر 1840: ستتخلى فرنسا عن دعمها لذرائع محمد علي في سوريا لكنها ستعلن للقوى الأوروبية أن مصر يجب أن تظل مستقلة بأي ثمن. وبعد ذلك اعترفت بريطانيا بالحكم الوراثي لمحمد علي لمصر: استعادت فرنسا مركزها في عام 1832. على الرغم من ذلك، فإن الخلاف بين تيير ولوي فيليپ أصبح نهائيًا على الفور. في 29 أكتوبر 1840، عندما قدم شارل دي ريموسات إلى مجلس الوزراء مسودة خطاب العرش، التي أعدها هپوليت پاسي، وجدها لوي فيليپ عدوانية للغاية. وبعد مناقشة قصيرة، قدم تيير وأقرانه استقالاتهم بشكل جماعي والتي قبلها الملك. وفي اليوم التالي، أرسل لوي فيليپ إلى مارشل سولت و گزو حتى يتمكنوا من العودة إلى باريس في أقرب وقت ممكن.

حكومة گيزو (1840–1848)

نهاية الملكية

بعد بعض الاضطرابات، أستبدل الملك گيزو بـ تيير الذي دعا إلى القمع. وبعد أن استقبلته القوات بعداء في كاروسيل، أمام قصر التويلري ، قرر الملك أخيرًا التنازل لصالح حفيده، فيليپ د ' أورليانز، وائتمان الوصاية على زوجة ابنه، هيلين دي ميكلمبورگ شفيرين. وقد كانت إشارته إلى ذلك عبثًا حيث أُعلن عن الجمهورية الثانية في 26 فبراير 1848، في ساحة الباستيل أمام عمود يوليو. لوي فيليپ، الذي ادعى أنه "ملك المواطن" المرتبط بالبلاد بموجب عقد سيادة شعبية الذي أسس شرعيته على أساسه، لم ير أن الشعب الفرنسي كان متحمساً لتوسيع جمهور الناخبين، إما من خلال خفض عتبة الضريبة الانتخابية، أو عن طريق إنشاء حق الاقتراع العام[citation needed]. على الرغم من أن نهاية نظام ملكية يوليو جعل فرنسا على شِفا حرب أهلية، إلا أن هذه الفترة تميزت أيضًا بتأثير الإبداع الفني والفكري.

انظر أيضاً

- France during the nineteenth century

- Liberalism and radicalism in France

- French art of the 19th century

- French literature of the 19th century

- History of science

- Politics of France

المراجع

- ^ Ronald Aminzade, Ballots and Barricades: Class Formation and Republican Politics in France, 1830-1871 (1993).

- ^ فرنسية: « Cela vaut mieux pour moi que le sacre de Reims ! »

- ^ Ronald Aminzade (1993). Ballots and barricades: class formation and republican politics in France, 1830–1871.

- ^ La Foire aux places, comédie-vaudeville in one act of Jean-François Bayard, played at the théâtre du Vaudeville on 25 September 1830, showed the solicitors, gathered in the antechamber of a minister: « Qu'on nous place / Et que justice se fasse. / Qu'on nous place / Tous en masse. / Que les placés / Soient chassés ! » (quoted by Antonetti 2002, p. 625) « Savez-vous ce que c'est qu'un carliste? interroge un humoriste. Un carliste, c'est un homme qui occupe un poste dont un autre homme a envie ! » (Antonetti 2002, p. 625)

- ^ David H. Pinkney (1972). The French Revolution of 1830.

- ^ Sudhir Hazareesingh (2015). How the French Think. Basic Books. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-465-06166-2.

- ^ فرنسية: « le principe de la révolution de juillet [...] ce n'est pas l'insurrection, [...] c'est la résistance à l'agression du pouvoir », Antonetti 2002, p. 656

- ^ La Petite Gazette Généalogique, Amicale Généalogie. "Le Choléra" (in الفرنسية). Archived from the original on 23 February 2006. Retrieved 10 April 2006.

- ^ فرنسية: « J'avais beau faire [...], dit-il, tout ce qui se faisait de bon était attribué à Casimir Périer, et les incidents malheureux retombaient à ma charge; aujourd'hui, au moins, on verra que c'est moi qui règne seul, tout seul. » (Rodolphe Apponyi, Journal, 18 mai 1832, quoted by Antonetti 2002, p. 689)

- ^ On 7 June 1832, Rudolf, Count of Apponyi noted in his Journal: « Il me semble que ce n'est que depuis hier qu'on peut dater le règne de Louis-Philippe; il paraît être persuadé qu'on ne peut réussir dans ce pays qu'avec de la force, et, dorénavant, il n'agira plus autrement. » (quoted by Antonetti 2002, p. 696)

- ^ فرنسية: coalition de tous les talents

- ^ Louis-Philippe to Soult, 17 April 1834, quoted by Antonetti 2002, p. 723

- ^ « On ne tue pas les fous, soit! mais on les enferme »، في Le Journal des débats (كما نقلها گي أنتونتي، Op. cit., p. 818)

- ^ انظر ميشل فوكو، Moi, Pierre Rivière, ayant égorgé ma mère, ma sœur et mon frère (Gallimard, 1973). وترجمتها: أنا، پيير ريڤيير، قد ذبحت أمي وأختي وشقيقي (Penguin, 1975)

للاستزادة

- Aston, Nigel. "Orleanism, 1780–1830," History Today, Oct 1988, Vol. 38 Issue 10, pp 41–47

- Beik, Paul. Louis Philippe and the July Monarchy (1965), short survey

- Collingham, H.A.C. The July Monarchy: A Political History of France, 1830–1848 (Longman, 1988)

- Howarth, T.E.B. Citizen-King: The Life of Louis Philippe, King of the French (1962).

- Jardin, Andre, and Andre-Jean Tudesq. Restoration and Reaction 1815–1848 (The Cambridge History of Modern France) (1988)

- Lucas-Dubreton, J. The Restoration and the July Monarchy (1929)

- Newman, Edgar Leon, and Robert Lawrence Simpson. Historical Dictionary of France from the 1815 Restoration to the Second Empire (Greenwood Press, 1987) online edition

التاريخ الثقافي

- Chu, Petra ten-Doesschate, and Gabriel P. Weisberg, eds. The popularization of images: Visual culture under the July Monarchy (Princeton University Press, 1994)

- Drescher, Seymour. "America and French Romanticism During the July Monarchy." American Quarterly (1959) 11#1 pp: 3-20. in JSTOR

- Margadant, Jo Burr. "Gender, Vice, and the Political Imaginary in Postrevolutionary France: Reinterpreting the Failure of the July Monarchy, 1830-1848," American Historical Review (1999) 194#5 pp. 1461-1496 in JSTOR

- Marrinan, Michael. Painting politics for Louis-Philippe: art and ideology in Orléanist France, 1830-1848 (Yale University Press, 1988)

- Mellon, Stanley. "The July Monarchy and the Napoleonic Myth." Yale French Studies (1960): 70-78. in JSTOR

التاريخ الاجتماعي والاقتصادي

- Charle, Christophe. A Social History of France in the Nineteenth Century (1994)

- Harsin, Jill. Barricades: The War of the Streets in Revolutionary Paris, 1830-1848 (2002)

- Kalman, Julie. "The unyielding wall: Jews and Catholics in Restoration and July monarchy France." French historical studies (2003) 26#4 pp: 661-686.

- Pinkney, David H. "Laissez-Fair or Intervention? Labor Policy in the First Months of the July Monarchy." in French Historical Studies, Vol. 3. No. 1. (Spring, 1963), pp. 123–128.

- Price, Roger. A Social History of Nineteenth-Century France (1987) 403pp. 403 pgs. online edition

- Stearns, Peter N. "Patterns of industrial strike activity in France during the July Monarchy." American Historical Review (1965): 371-394. in JSTOR

| July Monarchy

]].- Articles containing فرنسية-language text

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- Pages using infobox country with unknown parameters

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the symbol caption or type parameters

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2008

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2025

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2017

- ملكية يوليو

- مملكة فرنسا

- عقد 1830 في فرنسا

- عقد 1840 في فرنسا

- French monarchy

- التاريخ الحديث لفرنسا

- تأسيسات 1830 في فرنسا

- انحلالات 1848 في فرنسا

- أشخاص من ملكية يوليو

- القرن 19 في فرنسا