گرانيت

| ناري | |

| |

| التكوين | |

|---|---|

| أساسي | Potassium feldspar, plagioclase feldspar و quartz، كميات متفاونة من الموسكوڤيت، biotite, and hornblende-type amphiboles |

| ثانوي | Differing amounts of muscovite, biotite, and hornblende-type amphiboles |

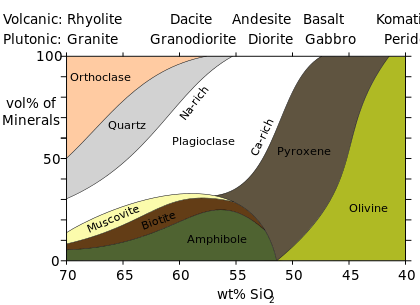

الجرانيت بالإنجليزية Granite ، هو عبارة عن صخر ناري جوفي تكون تحت درجات حرارة عالية يتميز بنسيج خش الحبيبات و لأنه برد ببطء تحت سطح الأرض مما سمح بنمو البلورات ووضوحها وهناك أنواع اخرى يتميز بها الجرانيت من حيث النسيج مثل النسيج البروفيري الذي يتميز بة الجرانيت عن باقي الصخور النارية وهذا النسيج يدل على أن الجرانيت تجمد على مرحلتين الأولى ببطئ والاخرى بسرعة مما أوجد نسيج بروفيري وهو خليط من البلورات الواضحة والدقيقة ويصنف كيميائيا بأنه صخر ناري حمضي لأن وزنه النوعي منخفض ولونه فاتح مما يدل على نسبة المعادن السيليكاتية تزيد فيه عن 65% مثل معدن الكوارتز والبلاجوكليز والبيوتيت والموسكوڤيت. أستخدم هذا النوع من الصخور أستخدام واسع لنحت التماثيل والأعمدة، وهو يتميز بتحمله لعوامل الحت والتعرية أكثر من أنواع الصخور الرسوبية. [1] أتت كلمة جرانيت من الكلمة اللاتينية granum وتعني حبيبات وذلك للإشارة للحبيبات المكونة لكتلة الجرانيت.

الجرانيت granite صخر ناري متبلور حُبيبي مؤلّف بصورة رئيسة من الكوارتز والفلدسبات feldspath والبلاجيوكلاز plagioclase، مع نسب قليلة من فلزات ملوّنة. يغطي الغرانيت نحو 22% من سطح الكرة الأرضية، بينما يغطي البازلت نحو 43%. منها وقيعان المحيطات.

تتكشّف الصخور الغرانيتية في مناطق واسعة من الكرة الأرضية، في المجنات boucliers القديمة القارية والسلاسل الجبلية، إضافة إلى مناطق أخرى واسعة في المحيطات بقيت مجهولة مدة طويلة من الزمن.

علم المعادن

حيّرت وفرة الصخور الجرانيتية وثبات تركيبها ومرورها بحالة الانصهار الجيولوجيِّين لمدة طويلة، حتى وضحت تعددية أنواعها الممثلة بالغرانيت الذي يتعلق تشكله بالحركات المولدة للجبال orogéniques ويوجد في مواقع السلاسل الجبلية. أمَّا الغرانيت الذي لايتعلق تشكله بهذه الحركات anorogéniques ويوجد في مواقع تباعد صفائح القشرة الأرضية، أو ضمن الصفيحة الواحدة، وبين هذين النوعين توجد مجموعات مهلية suites magmatiques غنية بالصخور الغرانيتية وبالصخور شبه الغرانيتية granitinoïdes المتبلورة في أعماق الكرة الأرضية مشكلة كتلاً ضخمة من الصخور البلوتونية (العميقة) plutoniques مكوّنة جذور البراكين التي على سطح الأرض.

توجد الصخور الغرانيتية على شكل صخور فاتحة أو بيضاء أو رمادية أو صفراء أو وردية اللون، ويمكن أن تكون أيضاً على شكل صخور حمراء أو خضراء أو زرقاء أو سوداء اللون. تتميّز هذه الصخور بقدود فلزاتها، فهي مرئية دوماً بالعين المجرّدة ويمكن أن يصل قدّها إلى سنتيمترات متعددة.

لا تمثّل الصخور الجرانيتية إلاّ ضرباً واحداً من مجموعة واسعة من الصخور شبه الغرانيتية. ويقصد بالصخور شبه الغرانيتية كل الصخور المشابهة للصخور الغرانيتية أو التي ترافقها. ويستحق هذا التعريف الواسع أن يضم، ليس الصخور الحبيبية المتبلورة بكاملها وحسب، وإنّما الصخور الأقل تبلوراً أيضاً، مثل صخور العروق filons والصخور البركانية التي يكون لها التركيب الكيميائي نفسه أو قريب منه.[2]

التركيب الكيميائي

فيما يلي المتوسط العالمي للنسب المتوسطة لمختلف المكونات الكيميائية في الگرانيتات المختلفة، بترتيب تنازلي حسب النسبة الوزنية:[3]

| SiO2 | 72.04% (silica) | |

| Al2O3 | 14.42% (alumina) | |

| K2O | 4.12% | |

| Na2O | 3.69% | |

| CaO | 1.82% | |

| FeO | 1.68% | |

| Fe2O3 | 1.22% | |

| MgO | 0.71% | |

| TiO2 | 0.30% | |

| P2O5 | 0.12% | |

| MnO | 0.05% |

بناء على 2485 تحليل

أظهر تحليل الصخور الغرانينية وأشباه الغرانيتية تباين مكوناتها الكيميائية، فالغرانيت «الوسط» يتميّز بغزارة العناصر الكيميائية الآتية: الأكسجين والسيلسيوم والألومينيوم والصوديوم والبوتاسيوم وفي بعض الحالات الكالسيوم. ويهيمن على مركبات هذه العناصر الكوارتز أو المرو SiO2 والفلدسبات (feldspath KalSi3O8- NaAlSi3O8 - CaAlSi2O8).

وتصنف فلزات الصخور شبه الغرانيتية في مجموعات عديدة أبرزها:

ـ الفلزات البيضاء أو عديمة اللون، وتتمثل بالكوارتز والفلزات السيليسية متعددة الشكل polymorphs، والفلدسبات وأشباه الفلدسبات feldspathoïdes (وهي فلزات ألومينية سيليكاتية سيليسها أقل من سيليس الفلدسبات ممثلة باللوسيت leucite والنفلين néphéline) (وهذه الفلزات الأخيرة ليست في الصخور الغرانيتية).

ـ الفلزات الملونة، وتدعى أيضاً الفلزات الحديدية المغنيزية، المتميزة حين الفحص المجهري لمقاطعها الرقيقة باختلاف ألوانها، وتتمثل بالأوليفين والبيروكسين والأمفيبول والبيوتيت وأكاسيد الحديد والتيتان.

ـ الفلزات الإضافية التي تحتوي على نزرة traces من عناصر كيميائية قليلة، مثل الزركون والأباتيت الذي يحوي الفسفور والتورمالين الي يحوي البورون، وفلزات أخرى تحوي كميات كبيرة من العناصر المعدنية مثل الكاسِّتريت الذي يحوي القصدير واليورانيت الذي يحوي اليورانيوم.

يبيّن التحليل الصِّيَغي modal الذي يُمثّل نسبة حجوم الفلزات المختلفة أنّ الصخورالغرانيتية هي من الصخور بياضية اللون leucocrates (من 60 إلى 90% من الفلزات البيضاء اللون) إلى تامة البياض hololeucocrates (أكثر من 90% من الفلزات البيضاء اللون). وهذه التغيّرات الكيميائية ضمن مجموعة الفلزات البيضاء اللون توجّه عملية التصنيف والتسمية.

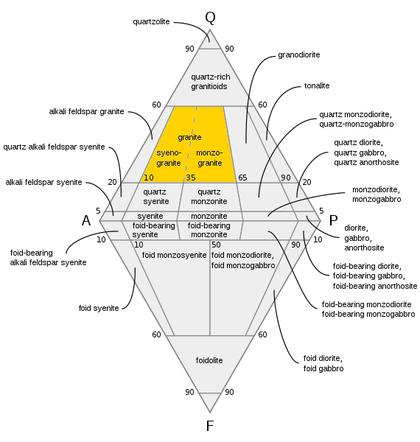

والتصنيف المعتمِد على الصيغة (تصنيف ستركايسن (ستركايسن A.Streckeisen ت. 1976) هو المرجَّح في الوقت الحاضر على التصانيف الأخرى المعتمدة على التركيب الكيميائي أو الكيميائي-الفلزي. فقد اعتمد هذا التصنيف على نسب أربع مجموعات من الفلزات البيضاء اللون، وهي:

1ـ الكوارتز والفلزات السيليسية متعددة الشكل.2ـ الفلدسباتات القلوية: البوتاسية والصودية والمتوسطة. 3ـ الفلدسباتات البلاجيوكلازية. 4ـ أشباه الفلدسبات.

وحتى يكون التصنيف أكثر كمالاً يُضاف إلى المجموعات المحدّدة:

ـ قرينة اللون (النسبة الحجمية للفلزات الملوّنة) باستخدام السابقة «بياضي leuco» (قرينة اللون أقل من 40%) و«متوسط meso» (تراوح هذه القرينة بين 40 و60%) و«سوادي mélano» (تكون هذه القرينة أعلى من 60%).

ـ الفلزات المميّزة حتى ولو كانت نادرة (فالغرانيت ذو فاياليت نادراً ما يحوي أكثر من 1% من هذا الفلز)، وكذلك حسب مرتبة نقصان الغزارة: فالغرانيت ذو الأمفيبول ـ البيوتيت يختلف عن الغرانيت ذي البيوتيت ـ الأمفيبول.

التفاعل

الأصل

الأصول الجيوكيميائية

تكون الجرانيت

An old, and largely discounted theory, granitization states that granite is formed in place by extreme metasomatism by fluids bringing in elements e.g. potassium and removing others e.g. calcium to transform the metamorphic rock into a granite. This was supposed to occur across a migrating front. The production of granite by metamorphic heat is difficult, but is observed to occur in certain amphibolite and granulite terrains. In-situ granitisation or melting by metamorphism is difficult to recognise except where leucosome and melanosome textures are present in gneisses. Once a metamorphic rock is melted it is no longer a metamorphic rock and is a magma, so these rocks are seen as a transitional between the two, but are not technically granite as they do not actually intrude into other rocks. In all cases, melting of solid rock requires high temperature, and also water or other volatiles which act as a catalyst by lowering the solidus temperature of the rock.

المجمّعات الگرانيتية Granite association

بدا في الستينيات أنّ مشكلة الصخور الغرانيتية قد تمّ حلّها، فأشباه الغرانيت التي هي الحد الأخير لعمليات التحوّل؛ تتشكّل فقط بتبلور مُهْل magmas صادر عن انصهار جزئي لقشرة القارات، غير أنّ الأخذ بالحسبان الصخور الغرانيتية الحقيقية التي عُثر عليها في قاع المحيطات، والتي لاتحتوي على أجزاء قارية المنشأ؛ أطلقت جدلاً في ضوء النتائج الجيودينامية géodynamiques، الجديدة. فبعد عمليات جرفٍ لقاع المحيط، على ضهرة dorsale رودريغ في المحيط الهندي، اكتُشفت صخور غرانيتية تقطع صخوراً بازلتية. وهذا يدلّ على أنّ بعض الصخور الغرانيتية كان لها المصدر نفسه للصخور البازلتية، أي إنّ مصدرها كان من المعطف manteau الأرضي.

وهكذا طُرحت مفاهيم جديدة في تشكيل الصخور الغرانيتية تتعلّق بمصادرها وبجيوديناميتها، فبعد فكرة صخر غرانيتي أحادي المنشأ monogénique (غرانيت واحد من مصدر واحد من القشرة القارية) جاءت فكرة غرانيتات عديدة المنشأ polygénique (صخور غرانيتية متعدّدة ومصادر متنوّعة)، وتقترح دراسة الكتل الغرانيتية الكبيرة إعادة تشكيلٍ للمجموعات المهلية والبيئة الجيودينامية. ويستند هذا التوجّه إلى ملاحظات علماء الطبيعة وطرائق التحاليل الفيزيائية والكيمياوية.

لايشكل تنوّع فلزات وكيمياء الصخور الغرانيتية الفلزي والكيميائي مظهراً عشوائياً، وإنّما يعكس تنوّعاً في مصادرها وتوسع ومجمّعاتها associations. ولذلك قُدّمت تصانيف عديدة منذ السبعينيات أهمّها ذلك التصنيف الذي يعدّ الزمر الغرانيتية متعلقة بالزمر البركانية. فصخور أشباه الغرانيت تتبلور في أعماق الكرة الأرضية مشكلة كتلاً ضخمة من الصخور البلوتونية العميقة المنشأ مكوّنة جذور البراكين التي على سطح الأرض. فالبركنة volcanisme والبلوتونية plutonisme هما وجهان لمظهر جيولوجي واحد ألا وهو: المهلية magmatisme.

إن المعيار الرئيس الذي يُحدّد تنوّع أشباه الغرانيت هو معيار البيئة الجيودينامية في لحظة توضع الكتلة الغرانيتية، فبعض الصخور الغرانيتية تظهر في منطقة تباعد صفائح القشرة الأرضية، أو في وسط الصفيحة الواحدة أي في منطقة غير معرضة للحركات المولدة للجبال orogénèse، ولذلك فهي صخور لا يتعلق تشكلها بتكوين الجبال. أمّا الصخور الجرانيتية الأخرى، التي تُشكل معظمها والموجودة في السلاسل الجبلية في لحظة تشكلها؛ فهي صخور يتعلق تشكلها بالحركات المولدة للجبال.

الصخور الگرانيتية التي لا يتعلق تشكلها بالحركات المولدة للجبال

تظهر في مواقع مستقرة نسبياً، وتكون معرضة بصورة رئيسة للتوسّع أو للانغراز تحت القارة. ومع ذلك فهي دوماً متزامنة مع فترات الحركات المولّدة للجبال على مستوى الكرة الأرضية. وتكون على القارات (إفريقيا وسكوتلندا وكورسيكا وغرينلندا) وعلى أرضيات قاع المحيطات (إيسلندا وكرگولن وسيشل) وهي متماثلة في الحالتين. إنّ مصدر هذه الصخور الغرانيتية غير المتعلقة بتكوين الجبال لايقع في القشرة الأرضية غير المتجانسة وإنّما في المعطف العلوي: فهي صخور جرانيتية معطفية mantéliques.

وتتميّز في الصخور غير المتعلقة بتكوين الجبال زمرتان: الزمرة التولئيتية tholéilitique (التوليئيت tholéite ضرب من البازلت لايحتوي على الأوليفين بل على كوارتز وفلدسبات تأخر ظهورها) والزمرة القلوية alcaline (وهي صخور نارية يتجاوز محتواها من الصوديوم والبوتاسيوم 10%). وهذا التقسيم صنعيٌّ نظراً لوجود زمر متوسطة انتقالية transitionnelles. ويستند هذا التصنيف إلى المحتوى القلوي ويُعَبَّر عنه بتزايدٍ مختلفٍ لنسب الفلزات البيضاء اللون.

الصخور الگرانيتية الكلسية - القلوية

تتميّز هذه الصخور بتعددية مظهرها بالنسبة إلى الصخور الجرانيتية التي يتعلق تشكلها بالحركات المولدة للجبال. فهي تحتل أمكنتها في السلاسل الجبلية عند تشكّلها وفي بيئات صفيحة المحيط المنغرز plaque océanique subductée، وفي الأقواس الجزيرية (اليابان)، وفي الهوامش القارية النشطة (جبال الأنديز)، وعند تصادم قارتين (جبال الهيمالايا). ويمكن أن تتتابع هذه الوضعيات من حيث الزمن والمكان وتكون مترافقة بمجمّعات مهلية مختلفة.

صخور الانصهار المجزأ الگرانيتية المتعلقة بتكون الجبال

تتفرّد فصيلة من الصخور الغرانيتية بغناها بالكوارتز مع وجود سيليكات ألومينية وغياب الصخور الأساسية المشابهة لها. وهذه الصخور الغرانيتية، المختلطة إلى حد بعيد مع التشكيلات المتحوّلة، تُكوّن مجموعة صخور الانصهار المجزأ anatexie. تكون صخور غرانيت الانصهار المجزأ غزيرة في المناطق الداخلية من السلاسل الجبلية الناجمة عن تصادم قارتين (نمط جبال هيمالايا)، وتتضمّن محتبسات متعدّدة من الصخور المتحولة ولكنّها نادراً ما تحتوي على محتبسات أساسية.

تهيمن الصخور الغرانيتية الكلسية-القلوية التي يتعلق تشكلها بتكوين الجبال، حيث تُشكّل 75% من مجموع الصخور الغرانيتية الكلية، بينما تشكل الصخور الجرانيتية غير المتعلقة بتكوين الجبال 25% فقط. وتوجد هذه الأخيرة على القارات، وكذلك في قيعان المحيطات، حيث تظهر على شكل عروق تنتشر في قشرة المحيطات، أو تتركّز في الجزر البارزة على سطح المحيطات. وتمنع الكثافة الضعيفة لصخور الغرانيت في هذه الجزر من اختفاء هذه الصخور في مناطق الانغراز subduction ، وتتيح لها الإسهام في زيادة حجم القارات في فترات الحركات المولّدة للجبال اللاحقة مرافقة بذلك الصخور الغرانيتية الكلسية ـ القلوية المتعلقة بتكوين الجبال.

أمّا صخور الانصهار الجرانيتية فهي من مصدر القشرة الأرضية وحسب، وتسهم بنسب غير معروفة تماماً في إعادة تدوير المواد القارية التي تُؤدّي إلى تركيز عناصر كيميائية يمكن استثمارها من الناحية الاقتصادية.

نظام التصنيف الأبجدي

تَرَدّي (إفساد) الصخور الگرانيتية

درست عمليات تَرَدّي alteration الصخور الجرانيتية أكثر من غيرها من الصخور، لأنها تغطي أكثر من 20% من القارات البارزة عن سطح البحار والمحيطات، ولتأثرها بالعوامل المناخية وتشكيلها غطاءً سميكاً من القشرة الأرضية بالمقارنة مع غيرها من الصخور الأخرى. ويرجع ذلك إلى أنّ الجرانيت صخر حبيبي مؤلّف من تجاور فلزات متداخل بعضها ببعض بأبعاد كبيرة نسبياً تُراوح، عموماً، بين بضعة أجزاء من الملّيمتر إلى بضعة سنتيمترات، من ناحية، وإلى تَكَوُّن الغرانيت، من ناحية أخرى، من صنفين مختلفين من الفلزات: يشتمل الصنف الأول على فلزات الكوارتز والفلدسبات البوتاسي والموسكوفيت (الميكا البيضاء)؛ ويشتمل الصنف الثاني على فلزات سهلة التفكك والتردي مثل البلاجيوكلاز والبيوتيت (الميكا السوداء).

وبناءً على ما تقدم، يجري تردي الصخور الغرانيتية، على سطح الكرة الأرضية، وفق نمطين كبيرين: ينجم النمط الأول عن عملية حلمهة hydrolyse خفيفة لصخور الجرانيت، وتصادف بصورة رئيسة في المناطق المعتدلة خاصة، والباردة والصحراوية الجافة، حيث تتحول هذه الصخور إلى رمال arénisation؛ وينجم النمط الثاني عن عملية حلمهة hydrolyse شديدة تتميّز بها المناطق المدارية والاستوائية، حيث تتحول هذه الصخور إلى تربة لاتريت latéritisation، وهنالك نمط ثالث من التردي يتوسط النمطين يعرّف بالتردي المتوسط، ويجري في مناطق البحر المتوسط الدافئة والمناطق القريبة من المناطق المدارية.

وفي نهاية المطاف، تتعرض الصخور الغرانيتية، المنتشرة على سطح الكرة الأرضية، إذا ما وجدت في شروط حلمهة خفيفة أو شديدة إلى تردٍ مناخي يؤدي في المنطقة المعتدلة، إلى فلزات خشنة أولية مقاومة كانت موجودة في الصخر الأصلي مثل الكوارتز والفلدسبات البوتاسي. أما في المناطق الانتقالية الحارة فتكون فلزاتها رملية ـ غضارية موروثة من الصخر الأصلي مثل الكوارتز والفلدسبات المفكّك وفلزات متغيّرة، مثل الفرميكوليت vermiculite الهيدروألوميني وفلزات جديدة التشكل، مثل الكاولينيت kaolinite، وأخيراً تُكَوِّن التشكيلات السطحية صخوراً مرنة في المناطق المدارية والاستوائية، مشكّلة بصورة رئيسة من الكاؤلينيت نتيجة لفقدان كبير لفلزات الفلدسبات.

الصعود و emplacement

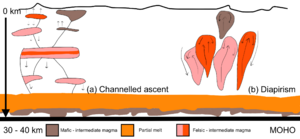

Granite magmas have a density of 2.4 Mg/m3, much less than the 2.8 Mg/m3 of high-grade metamorphic rock. This gives them tremendous buoyancy, so that ascent of the magma is inevitable once enough magma has accumulated. However, the question of precisely how such large quantities of magma are able to shove aside country rock to make room for themselves (the room problem) is still a matter of research.[4]

Two main mechanisms are thought to be important:

- Stokes diapir

- Fracture propagation

Of these two mechanisms, Stokes diapirism has been favoured for many years in the absence of a reasonable alternative. The basic idea is that magma will rise through the crust as a single mass through buoyancy. As it rises, it heats the wall rocks, causing them to behave as a power-law fluid and thus flow around the intrusion allowing it to pass without major heat loss.[5] This is entirely feasible in the warm, ductile lower crust where rocks are easily deformed, but runs into problems in the upper crust which is far colder and more brittle. Rocks there do not deform so easily: for magma to rise as a diapir it would expend far too much energy in heating wall rocks, thus cooling and solidifying before reaching higher levels within the crust.

Fracture propagation is the mechanism preferred by many geologists as it largely eliminates the major problems of moving a huge mass of magma through cold brittle crust. Magma rises instead in small channels along self-propagating dykes which form along new or pre-existing fracture or fault systems and networks of active shear zones.[6] As these narrow conduits open, the first magma to enter solidifies and provides a form of insulation for later magma.

These mechanisms can operate in tandem. For example, diapirs may continue to rise through the brittle upper crust through stoping, where the granite cracks the roof rocks, removing blocks of the overlying crust which then sink to the bottom of the diapir while the magma rises to take their place. This can occur as piecemeal stopping (stoping of small blocks of chamber roof), as cauldron subsidence (collapse of large blocks of chamber roof), or as roof foundering (complete collapse of the roof of a shallow magma chamber accompanied by a caldera eruption.) There is evidence for cauldron subsidence at the Mt. Ascutney intrusion in eastern Vermont.[7] Evidence for piecemeal stoping is found in intrusions that are rimmed with igneous breccia containing fragments of country rock.[4]

Assimilation is another mechanism of ascent, where the granite melts its way up into the crust and removes overlying material in this way. This is limited by the amount of thermal energy available, which must be replenished by crystallization of higher-melting minerals in the magma. Thus, the magma is melting crustal rock at its roof while simultaneously crystallizing at its base. This results in steady contamination with crustal material as the magma rises. This may not be evident in the major and minor element chemistry, since the minerals most likely to crystallize at the base of the chamber are the same ones that would crystallize anyway, but crustal assimilation is detectable in isotope ratios.[8] Heat loss to the country rock means that ascent by assimilation is limited to distance similar to the height of the magma chamber.[9]

الإشعاع الطبيعي

Granite is a natural source of radiation, like most natural stones. Potassium-40 is a radioactive isotope of weak emission, and a constituent of alkali feldspar, which in turn is a common component of granitic rocks, more abundant in alkali feldspar granite and syenites. Some granites contain around 10 to 20 parts per million (ppm) of uranium. By contrast, more mafic rocks, such as tonalite, gabbro and diorite, have 1 to 5 ppm uranium, and limestones and sedimentary rocks usually have equally low amounts.

Many large granite plutons are sources for palaeochannel-hosted or roll front uranium ore deposits, where the uranium washes into the sediments from the granite uplands and associated, often highly radioactive pegmatites.

Cellars and basements built into soils over granite can become a trap for radon gas,[10] which is formed by the decay of uranium.[11] Radon gas poses significant health concerns and is the number two cause of lung cancer in the US behind smoking.[12]

Thorium occurs in all granites.[13] Conway granite has been noted for its relatively high thorium concentration of 56±6 ppm.[14]

There is some concern that some granite sold as countertops or building material may be hazardous to health.[15] Dan Steck of St. Johns University has stated[16] that approximately 5% of all granite is of concern, with the caveat that only a tiny percentage of the tens of thousands of granite slab types have been tested. Resources from national geological survey organizations are accessible online to assist in assessing the risk factors in granite country and design rules relating, in particular, to preventing accumulation of radon gas in enclosed basements and dwellings.

A study of granite countertops was done (initiated and paid for by the Marble Institute of America) in November 2008 by National Health and Engineering Inc. of USA. In this test, all of the 39 full-size granite slabs that were measured for the study showed radiation levels well below the European Union safety standards (section 4.1.1.1 of the National Health and Engineering study) and radon emission levels well below the average outdoor radon concentrations in the US.[17]

الصناعة والاستخدامات

Granite and related marble industries are considered one of the oldest industries in the world, existing as far back as Ancient Egypt.[18] Major modern exporters of granite include China, India, Italy, Brazil, Canada, Germany, Sweden, Spain and the United States.[19][20]

قديماً

The Red Pyramid of Egypt (ح. 2590 BC), named for the light crimson hue of its exposed limestone surfaces, is the third largest of Egyptian pyramids. Pyramid of Menkaure, likely dating 2510 BC, was constructed of limestone and granite blocks. The Great Pyramid of Giza (c. 2580 BC) contains a granite sarcophagus fashioned of "Red Aswan Granite". The mostly ruined Black Pyramid dating from the reign of Amenemhat III once had a polished granite pyramidion or capstone, which is now on display in the main hall of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (see Dahshur). Other uses in Ancient Egypt include columns, door lintels, sills, jambs, and wall and floor veneer.[21] How the Egyptians worked the solid granite is still a matter of debate. Tool marks described by the Egyptologist Anna Serotta indicate the use of flint tools on finer work with harder stones, e.g. when producing the hieroglyphic inscriptions.[22] Patrick Hunt[23] has postulated that the Egyptians used emery, which has greater hardness.

The Seokguram Grotto in Korea is a Buddhist shrine and part of the Bulguksa temple complex. Completed in 774 AD, it is an artificial grotto constructed entirely of granite. The main Buddha of the grotto is a highly regarded piece of Buddhist art,[24] and along with the temple complex to which it belongs, Seokguram was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1995.[25]

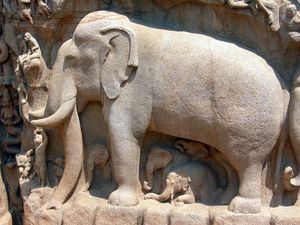

Rajaraja Chola I of the Chola Dynasty in South India built the world's first temple entirely of granite in the 11th century AD in Tanjore, India. The Brihadeeswarar Temple dedicated to Lord Shiva was built in 1010. The massive Gopuram (ornate, upper section of shrine) is believed to have a mass of around 81 tonnes. It was the tallest temple in south India.[26]

Imperial Roman granite was quarried mainly in Egypt, and also in Turkey, and on the islands of Elba and Giglio. Granite became "an integral part of the Roman language of monumental architecture".[27] The quarrying ceased around the third century AD. Beginning in Late Antiquity the granite was reused, which since at least the early 16th century became known as spolia. Through the process of case-hardening, granite becomes harder with age. The technology required to make tempered metal chisels was largely forgotten during the Middle Ages. As a result, Medieval stoneworkers were forced to use saws or emery to shorten ancient columns or hack them into discs. Giorgio Vasari noted in the 16th century that granite in quarries was "far softer and easier to work than after it has lain exposed" while ancient columns, because of their "hardness and solidity have nothing to fear from fire or sword, and time itself, that drives everything to ruin, not only has not destroyed them but has not even altered their colour."[27]

حديثا

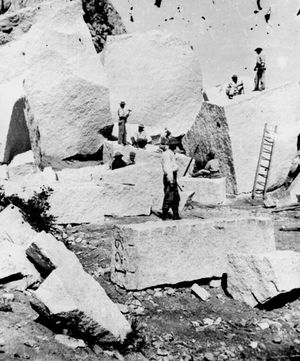

النحت والنُصُب

In some areas, granite is used for gravestones and memorials. Granite is a hard stone and requires skill to carve by hand. Until the early 18th century, in the Western world, granite could be carved only by hand tools with generally poor results.

A key breakthrough was the invention of steam-powered cutting and dressing tools by Alexander MacDonald of Aberdeen, inspired by seeing ancient Egyptian granite carvings. In 1832, the first polished tombstone of Aberdeen granite to be erected in an English cemetery was installed at Kensal Green Cemetery. It caused a sensation in the London monumental trade and for some years all polished granite ordered came from MacDonald's.[29] As a result of the work of sculptor William Leslie, and later Sidney Field, granite memorials became a major status symbol in Victorian Britain. The royal sarcophagus at Frogmore was probably the pinnacle of its work, and at 30 tons one of the largest. It was not until the 1880s that rival machinery and works could compete with the MacDonald works.

Modern methods of carving include using computer-controlled rotary bits and sandblasting over a rubber stencil. Leaving the letters, numbers, and emblems exposed and the remainder of the stone covered with rubber, the blaster can create virtually any kind of artwork or epitaph.

The stone known as "black granite" is usually gabbro, which has a completely different chemical composition.[30]

المباني

Granite has been extensively used as a dimension stone and as flooring tiles in public and commercial buildings and monuments. Aberdeen in Scotland, which is constructed principally from local granite, is known as "The Granite City". Because of its abundance in New England, granite was commonly used to build foundations for homes there. The Granite Railway, America's first railroad, was built to haul granite from the quarries in Quincy, Massachusetts, to the Neponset River in the 1820s.[31]

الهندسة

Engineers have traditionally used polished granite surface plates to establish a plane of reference, since they are relatively impervious, inflexible, and maintain good dimensional stability. Sandblasted concrete with a heavy aggregate content has an appearance similar to rough granite, and is often used as a substitute when use of real granite is impractical. Granite tables are used extensively as bases or even as the entire structural body of optical instruments, CMMs, and very high precision CNC machines because of granite's rigidity, high dimensional stability, and excellent vibration characteristics. A most unusual use of granite was as the material of the tracks of the Haytor Granite Tramway, Devon, England, in 1820.[32] Granite block is usually processed into slabs, which can be cut and shaped by a cutting center.[33] In military engineering, Finland planted granite boulders along its Mannerheim Line to block invasion by Russian tanks in the Winter War of 1939–40.[34]

الرصف

Granite is used as a pavement material. This is because it is extremely durable, permeable and requires little maintenance. For example, in Sydney, Australia black granite stone is used for the paving and kerbs throughout the Central Business District.[35]

Curling stones

Curling stones are traditionally fashioned of Ailsa Craig granite. The first stones were made in the 1750s, the original source being Ailsa Craig in Scotland. Because of the rarity of this granite, the best stones can cost as much as US$1,500. Between 60 and 70 percent of the stones used today are made from Ailsa Craig granite. Although the island is now a wildlife reserve, it is still quarried under license for Ailsa granite by Kays of Scotland for curling stones.[36]

تسلق الصخور

Granite is one of the rocks most prized by climbers, for its steepness, soundness, crack systems, and friction.[37] Well-known venues for granite climbing include the Yosemite Valley, the Bugaboos, the Mont Blanc massif (and peaks such as the Aiguille du Dru, the Mourne Mountains, the Adamello-Presanella Alps, the Aiguille du Midi and the Grandes Jorasses), the Bregaglia, Corsica, parts of the Karakoram (especially the Trango Towers), the Fitzroy Massif and the Paine Massif in Patagonia, Baffin Island, Ogawayama, the Cornish coast, the Cairngorms, Sugarloaf Mountain in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and the Stawamus Chief, British Columbia, Canada.

معرض الصور

Granite was used for setts on the St. Louis riverfront and for the piers of the Eads Bridge (background)

القمم الگرانيتية لتورِّس دل پاينه في پتاگونيا التشيلية

Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, is actually a granite arête and is a popular rock climbing destination

Rixö red granite quarry in Lysekil, Sweden

Granite in Auyuittuq National Park on Baffin Island, Canada

Granite in Paarl, South Africa

A granite peak at Huangshan, China

The Cheesewring, a granite tor in England

انظر أيضا

- قائمة المعادن

- قائمة أنواع الصخور

- صخور نارية

- Dimension stone

- Skarn

- Greisen

- Aplite

- Batholith

- نيو هامپشر, the "Granite State"

- Barre (town), Vermont "Granite Capital of the World", home of the Rock of Ages Corporation

- Elberton, Georgia, the "Granite Capital of the World"

- Aberdeen, Scotland's third largest city nicknamed "The Granite City"

- Quartz monzonite

- Fall River Granite

المصادر

- ^ Kumagai, Naoichi (15 February 1978). "Long-term Creep of Rocks: Results with Large Specimens Obtained in about 20 Years and Those with Small Specimens in about 3 Years". Journal of the Society of Materials Science (Japan). Japan Energy Society. 27 (293): 157–161. Retrieved 06-16-2008.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ فؤاد العجل. "الغرانيت". الموسوعة العربية.

- ^ Harvey Blatt and Robert J. Tracy (1996). Petrology (2nd edition ed.). New York: Freeman. p. 66.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Text "ISBN 0-7167-2438-3" ignored (help) - ^ أ ب Philpotts & Ague 2009, p. 80.

- ^ Weinberg, R. F.; Podladchikov, Y. (1994). "Diapiric ascent of magmas through power law crust and mantle". Journal of Geophysical Research. 99 (B5): 9543. Bibcode:1994JGR....99.9543W. doi:10.1029/93JB03461. S2CID 19470906.

- ^ Clemens, John (1998). "Observations on the origins and ascent mechanisms of granitic magmas". Journal of the Geological Society of London. 155 (Part 5): 843–51. Bibcode:1998JGSoc.155..843C. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.155.5.0843. S2CID 129958999.

- ^ Blatt & Tracy 1996, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Philpotts & Ague 2009, pp. 347–350.

- ^ Oxburgh, E. R.; McRae, Tessa (27 April 1984). "Physical constraints on magma contamination in the continental crust: an example, the Adamello complex". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 310 (1514): 457–472. Bibcode:1984RSPTA.310..457O. doi:10.1098/rsta.1984.0004. S2CID 120776326.

- ^ US EPA, OAR (2015-05-04). "Granite Countertops and Radiation". www.epa.gov (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ "Decay series of Uranium". Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ^ "Radon and Cancer: Questions and Answers". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ^ Hubbert, M. King (June 1956). "Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels" (PDF). Shell Oil Company/American Petroleum Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-27. Retrieved 2014-11-10.

- ^ Adams, J. A.; Kline, M. C.; Richardson, K. A.; Rogers, J. J. (1962). "The Conway Granite of New Hampshire As a Major Low-Grade Thorium Resource". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 48 (11): 1898–905. Bibcode:1962PNAS...48.1898A. doi:10.1073/pnas.48.11.1898. PMC 221093. PMID 16591014.

- ^ "Granite Countertops and Radiation". United States Environmental Protection Agency. 4 May 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Steck, Daniel J. (2009). "Pre- and Post-Market Measurements of Gamma Radiation and Radon Emanation from a Large Sample of Decorative Granites" (PDF). Nineteenth International Radon Symposium. pp. 28–51.

- ^ Environmental Health and Engineering (2008). "Natural Stone Countertops and Radon" (PDF). Archived from the original on 3 November 2010. Retrieved 2023-02-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Nelson L. Nemerow (27 January 2009). Environmental Engineering: Environmental Health and Safety for Municipal Infrastructure, Land Use and Planning, and Industry. John Wiley & Sons. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-470-08305-5.

- ^ Parmodh Alexander (15 January 2009). A Handbook of Minerals, Crystals, Rocks and Ores. New India Publishing. p. 585. ISBN 978-81-907237-8-7.

- ^ "Where Does the Hardest Granite Come From?". George Stone (in الإنجليزية). 2025-02-17. Retrieved 2025-05-14.

- ^ James A. Harrell. "Decorative Stones in the Pre-Ottoman Islamic Buildings of Cairo, Egypt". Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ Serotta, Anna (2023-12-19). "Reading Tool Marks on Egyptian Stone Sculpture". Rivista del Museo Egizio. 7. doi:10.29353/rime.2023.5098. ISSN 2611-3295.

- ^ "Egyptian Genius: Stoneworking for Eternity". Archived from the original on 2007-10-14. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ Sculptures of Unified Silla: 통일신라의 조각. 국립중앙박물관. 8 July 2015. ISBN 9788981641306.

- ^ "Seokguram Grotto [UNESCO World Heritage] (경주 석굴암)".

- ^ Heitzman, James (1991). "Ritual Polity and Economy: The Transactional Network of an Imperial Temple in Medieval South India". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. BRILL. 34 (1/2): 23–54. doi:10.1163/156852091x00157. JSTOR 3632277.

- ^ أ ب Waters, Michael (2016). "Reviving Antiquity with Granite: Spolia and the Development of Roman Renaissance Architecture". Architectural History. 59: 149–179. doi:10.1017/arh.2016.5.

- ^ De Matteo, Giovanna (12 September 2020). "Leopoldina e Teresa Cristina: descubra o que aconteceu com as "mães do Brasil"" (in البرتغالية). Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Friends of West Norwood Cemetery newsletter 71 Alexander MacDonald (1794–1860) – Stonemason,

- ^ "Gabbro". Geology.com. Retrieved 2022-01-25.

- ^ Brayley, A.W. (1913). History of the Granite Industry of New England (2018 ed.). Franklin Classics. ISBN 0342278657. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ Ewans, M.C. (1966). The Haytor Granite Tramway and Stover Canal. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

- ^ Bai, Shuo-wei; Zhang, Jin-sheng; Wang, Zhi (January 2016). "Selection of a sustainable technology for cutting granite block into slabs". Journal of Cleaner Production. 112: 2278–2291. Bibcode:2016JCPro.112.2278B. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.052.

- ^ Chersicla, Rick (January–March 2017). "What Free Men Can Do: The Winter War, the Use of Delay, and Lessons for the 21st Century" (PDF). Infantry: 63. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Sydney Streets technical specifications". November 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ Roach, John (October 27, 2004). "National Geographic News — Puffins Return to Scottish Island Famous for Curling Stones". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on November 2, 2004.

- ^ Green, Stewart. "3 Types of Rock for Climbing: Granite, Sandstone & Limestone: The Geology of Rock Climbing". Liveabout.dotcom. Dotdash. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

وصلات خارجية

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 errors: unrecognized parameter

- CS1 errors: extra text: edition

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- CS1 البرتغالية-language sources (pt)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- صخور نارية

- علم النفط

- جرانيت

- Felsic rocks

- الرموز الوطنية لفنلندا

- صخور پلوتونية

- Sculpture materials

- رموز وسكنسن

- معادن صناعية