كهرمان

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| علم الإحاثة |

|---|

|

|

بوابة علم الإحاثة التصنيف |

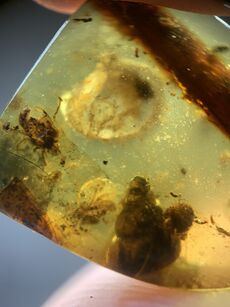

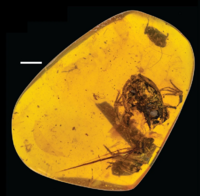

الكهرمان Amber، هو راتنج متحجر من الأشجار الصنوبرية المنقرضة في بعض مناطق الغابات الصنوبرية العالمية وتحجرت وتشكلت قبل الآف السنين. الكهرمان لا يعتبر إطلاقا من مجموعات الأحجار الكريمة المعدنية الأساسية وإنما مواد عضوية متحجرة بمعنى من المواد النباتية العضوية. ولذلك هو هش ويبعث روائح الشجر الصنوبري عند فركه باليد أو احتراقة ويتدرج لونه في العادة من الأصفر إلى أصفر الداكن, ويوجد اما باشكال دائرية أو كتل غير منتظمة الشكل أو بشكل حبوب أو قطرات. هو هش قليلا ويبعث رائحة مقبولة عند فركه باليدين, وعند احراقه يصدر لهبا لامعا ورائحة زكية ويصبح كهربائي سلبيا بالاحتكاك. توجد أصناف من الحشرات المنقرضة مغلفة أحيانا في عينات الكهرمان.

تجدر الإشارة إلى أن الكهرمان الدومينيكي لا يتم تحسينه بالحرارة، أو بعلاج النفط، كما ولا يتم تعقيمه بالموصدة مثل الكثير من عنبر دول البلطيق. أضف إلى أنه لا يتم استخدام أي كهرمان مضغوط. فهذه التقنيات ليست معروفة حتى في تلك المناطق. كما وأن الألوان الزرقاء، والخضراء، والأرجوانية يمكن رؤيتها بسبب أشعة الشمس ما فوق البنفسجية ومصادر أخرى للنور. وهذا يعني أنه الكهرمان فلوري ونتيجة لذلك فيمكنه أيضا أن يتميز عن الكهرمان الذي تم تلوينه وتحسينه إصطناعيا بكونه عنبرا أصليا.

التاريخ أو التسمية

الكهرمان لفظ فارسي عربيه العنبر الأشهب.[2] أصله غير معروف، والظاهر أنه مشتق من لفظة كهرم بزيادة الألف والنون للنسبة، معناها الأعمل والأشد تأثيرا، وأصلها كرتمه بمعنى المؤثر والعامل.[3] كلمة كهرمان بالتركية أو قهرمان معناها البطل.

Theophrastus discussed amber in the 4th century BCE, as did Pytheas (ح. 330 BCE), whose work "On the Ocean" is lost, but was referenced by Pliny, according to whose Natural History:[4]

Pytheas says that the Gutones, a people of Germany, inhabit the shores of an estuary of the Ocean called Mentonomon,[5] their territory extending a distance of six thousand stadia; that, at one day's sail from this territory, is the Isle of Abalus, upon the shores of which, amber is thrown up by the waves in spring, it being an excretion of the sea in a concrete form; as, also, that the inhabitants use this amber by way of fuel, and sell it to their neighbors, the Teutones.

Earlier Pliny says that Pytheas refers to a large island—three days' sail from the Scythian coast and called Balcia by Xenophon of Lampsacus (author of a fanciful travel book in Greek)—as Basilia—a name generally equated with Abalus.[6] Given the presence of amber, the island could have been Heligoland, Zealand, the shores of Gdańsk Bay, the Sambia Peninsula or the Curonian Lagoon, which were historically the richest sources of amber in northern Europe.[citation needed] There were well-established trade routes for amber connecting the Baltic with the Mediterranean (known as the "Amber Road"). Pliny states explicitly that the Germans exported amber to Pannonia, from where the Veneti distributed it onwards.

The ancient Italic peoples of southern Italy used to work amber; the National Archaeological Museum of Siritide (Museo Archeologico Nazionale della Siritide) at Policoro in the province of Matera (Basilicata) displays important surviving examples. It has been suggested that amber used in antiquity, as at Mycenae and in the prehistory of the Mediterranean, came from deposits in Sicily.[7]

Pliny also cites the opinion of Nicias (ح. 470–413 BCE), according to whom amber

is a liquid produced by the rays of the sun; and that these rays, at the moment of the sun's setting, striking with the greatest force upon the surface of the soil, leave upon it an unctuous sweat, which is carried off by the tides of the Ocean, and thrown up upon the shores of Germany.

Besides the fanciful explanations according to which amber is "produced by the Sun", Pliny cites opinions that are well aware of its origin in tree resin, citing the native Latin name of succinum (sūcinum, from sucus "juice").[8] In Book 37, section XI of Natural History, Pliny wrote:

Amber is produced from a marrow discharged by trees belonging to the pine genus, like gum from the cherry, and resin from the ordinary pine. It is a liquid at first, which issues forth in considerable quantities, and is gradually hardened [...] Our forefathers, too, were of opinion that it is the juice of a tree, and for this reason gave it the name of "succinum" and one great proof that it is the produce of a tree of the pine genus, is the fact that it emits a pine-like smell when rubbed, and that it burns, when ignited, with the odour and appearance of torch-pine wood.[9]

He also states that amber is also found in Egypt and India, and he even refers to the electrostatic properties of amber, by saying that "in Syria the women make the whorls of their spindles of this substance, and give it the name of harpax [from ἁρπάζω, "to drag"] from the circumstance that it attracts leaves towards it, chaff, and the light fringe of tissues".

The Romans traded for amber from the shores of the southern Baltic at least as far back as the time of Nero.[10]

Amber has a long history of use in China, with the first written record from 200 BCE.[11] Early in the 19th century, the first reports of amber found in North America came from discoveries in New Jersey along Crosswicks Creek near Trenton, at Camden, and near Woodbury.[12]

المكونات والتكوين

Amber is heterogeneous in composition, but consists of several resinous bodies[clarify] more or less soluble in alcohol, ether and chloroform, associated with an insoluble bituminous substance. Amber is a macromolecule formed by free radical polymerization[13] of several precursors in the labdane family, for example, communic acid, communol, and biformene.[14][15] These labdanes are diterpenes (C20H32) and trienes, equipping the organic skeleton with three alkene groups for polymerization. As amber matures over the years, more polymerization takes place as well as isomerization reactions, crosslinking and cyclization.[16][13]

Most amber has a hardness between 2.0 and 2.5 on the Mohs scale, a refractive index of 1.5–1.6, a specific gravity between 1.06 and 1.10, and a melting point of 250–300 °C.[17] Heated above 200 °C (392 °F), amber decomposes, yielding an oil of amber, and leaves a black residue which is known as "amber colophony", or "amber pitch"; when dissolved in oil of turpentine or in linseed oil this forms "amber varnish" or "amber lac".[14]

Impurities are quite often present, especially when the resin has dropped onto the ground, so the material may be useless except for varnish-making. Such impure amber is called firniss.[18] Such inclusion of other substances can cause the amber to have an unexpected color. Pyrites may give a bluish color. Bony amber owes its cloudy opacity to numerous tiny bubbles inside the resin.[19] However, so-called black amber is really a kind of jet.[20] In darkly clouded and even opaque amber, inclusions can be imaged using high-energy, high-contrast, high-resolution X-rays.[21]

التشكل

Molecular polymerization,[13] resulting from high pressures and temperatures produced by overlying sediment, transforms the resin first into copal. Sustained heat and pressure drives off terpenes and results in the formation of amber.[22] For this to happen, the resin must be resistant to decay. Many trees produce resin, but in the majority of cases this deposit is broken down by physical and biological processes. Exposure to sunlight, rain, microorganisms, and extreme temperatures tends to disintegrate the resin. For the resin to survive long enough to become amber, it must be resistant to such forces or be produced under conditions that exclude them.[23] Fossil resins from Europe fall into two categories, the Baltic ambers and another that resembles the Agathis group. Fossil resins from the Americas and Africa are closely related to the modern genus Hymenaea,[24] while Baltic ambers are thought to be fossil resins from plants of the family Sciadopityaceae that once lived in north Europe.[25]

The abnormal development of resin in living trees (succinosis) can result in the formation of amber.[26]

الاستخلاص والمعالجة

الانتشار

تم الحصول عليه في العصور القديمة من ساحل بحر البلطيق الجنوبي وجمهورية الدومينيكان ما زال موجودا إلى الآن. ويوجد أيضا كميات صغيرة في صقلية، رومانيا، سايبيريا، جرينلند، مينامار (المعروفة سابقا ببورما)، أستراليا، والولايات المتحدة.وتعتبر بلدان البلطيق وامتدادها شرقا إلى روسيا وتتحجر فية أنواع من الحشرات والقوارض تختلف عن مناطق أخرى وبخاصة اجزاء من سيبيريا من أكبر مخزونات العالم ومن ثم تأتي دولة الدومنيكان ولكل منها جودة خاصة به يستعمل الكهرمان في الفنون وفي صناعة المجوهرات، حمالات السيجار، وسدادات الانابيب.

المعالجة

المظهر

يتكون العنبر من مادة شبة صلبة غير متبلورة عضوية وغير منتظمة تفرز عن طريق الجيوب والقنوات خلايا النباتات. يعتبر العنبر متغاير الخصائص من حيث التركيب ولكنه متناسق من حيث الأجساد الراتينجية المتعددة فهو أكثر ميولا للذوبان في الكحول وسائل الأثير والكلوروفورم والتي ترتبط وتتحد مع عناصر أخرى (مادة حمرية) التي لا تذوب أو تتحلل، ويعتبر الكهرمان مجموعة من عناصر كيمائيه المتبلمرة وهي أتحادات جزئيين أو أكثر من مركب ما لتشكيل مركب ذي وزن جزئي أكبر بمعنى تحول مركب ما إلى آخر من أجزاء عدة متماثلة.ولانه لين ولزج فانه يحتوي في ثناياه في كثير من الأحيان حشرات والفقاريات ألصغيره وبذور أو أجسام غريبة التي تلتصق به خلال مرحلة الانتقال إلى حالة التحجر وتوجد أيضا أصناف من الحشرات المنقرض مغلفة أحيانا في عينات الكهرمان.

اللون

بسبب تنوع الشجر الصمغي المتحجر فقد تنوعت أنواع وألوان وأشكال العنبر, فالاسم عنبر تعني اللون الأصفر أو البرتقالي لكن ألوانه تبدأ من الأبيض - الأصفر - البرتقالي - احمر- البني يصل لدرجة الأسود، ويتدرج كل لونه ما بين درجات المزيج اللوني فمثلا من اصفر قاتم إلى اصفر شاحب ليموني، وهناك ألوان نادرة مثل الأحمر العنبري ويطلق عليه اسم العنبر الأحمر والعنبر الأخضر وهناك أنواع نادرة جدا تحمل اللون الأزرق.

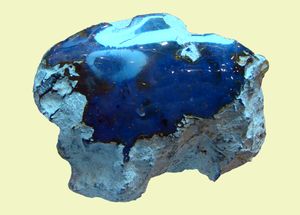

Amber occurs in a range of different colors. As well as the usual yellow-orange-brown that is associated with the color "amber", amber can range from a whitish color through a pale lemon yellow, to brown and almost black. Other uncommon colors include red amber (sometimes known as "cherry amber"), green amber, and even blue amber, which is rare and highly sought after.[27]

Yellow amber is a hard fossil resin from evergreen trees, and despite the name it can be translucent, yellow, orange, or brown colored. Known to the Iranians by the Pahlavi compound word kah-ruba (from kah "straw" plus rubay "attract, snatch", referring to its electrical properties[28]), which entered Arabic as kahraba' or kahraba (which later became the Arabic word for electricity, كهرباء kahrabā'), it too was called amber in Europe (Old French and Middle English ambre). Found along the southern shore of the Baltic Sea, yellow amber reached the Middle East and western Europe via trade. Its coastal acquisition may have been one reason yellow amber came to be designated by the same term as ambergris. Moreover, like ambergris, the resin could be burned as an incense. The resin's most popular use was, however, for ornamentation—easily cut and polished, it could be transformed into beautiful jewelry. Much of the most highly prized amber is transparent, in contrast to the very common cloudy amber and opaque amber. Opaque amber contains numerous minute bubbles. This kind of amber is known as "bony amber".[29]

Although all Dominican amber is fluorescent, the rarest Dominican amber is blue amber. It turns blue in natural sunlight and any other partially or wholly ultraviolet light source. In long-wave UV light it has a very strong reflection, almost white. Only about 100 kg (220 lb) is found per year, which makes it valuable and expensive.[30]

Sometimes amber retains the form of drops and stalactites, just as it exuded from the ducts and receptacles of the injured trees.[19] It is thought that, in addition to exuding onto the surface of the tree, amber resin also originally flowed into hollow cavities or cracks within trees, thereby leading to the development of large lumps of amber of irregular form.

التصنيف

Amber can be classified into several forms. Most fundamentally, there are two types of plant resin with the potential for fossilization. Terpenoids, produced by conifers and angiosperms, consist of ring structures formed of isoprene (C5H8) units.[31] Phenolic resins are today only produced by angiosperms, and tend to serve functional uses. The extinct medullosans produced a third type of resin, which is often found as amber within their veins.[31] The composition of resins is highly variable; each species produces a unique blend of chemicals which can be identified by the use of pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry.[31] The overall chemical and structural composition is used to divide ambers into five classes.[32][33] There is also a separate classification of amber gemstones, according to the way of production.[citation needed]

الدرجة 1

This class is by far the most abundant. It comprises labdatriene carboxylic acids such as communic or ozic acids.[32] It is further split into three sub-classes. Classes Ia and Ib utilize regular labdanoid diterpenes (e.g. communic acid, communol, biformenes), while Ic uses enantio labdanoids (ozic acid, ozol, enantio biformenes).[34]

Class Ia includes Succinite (= 'normal' Baltic amber) and Glessite.[33] They have a communic acid base, and they also include much succinic acid.[32] Baltic amber yields on dry distillation succinic acid, the proportion varying from about 3% to 8%, and being greatest in the pale opaque or bony varieties. The aromatic and irritating fumes emitted by burning amber are mainly from this acid. Baltic amber is distinguished by its yield of succinic acid, hence the name succinite. Succinite has a hardness between 2 and 3, which is greater than many other fossil resins. Its specific gravity varies from 1.05 to 1.10.[14] It can be distinguished from other ambers via infrared spectroscopy through a specific carbonyl absorption peak. Infrared spectroscopy can detect the relative age of an amber sample. Succinic acid may not be an original component of amber but rather a degradation product of abietic acid.[35]

Class Ib ambers are based on communic acid; however, they lack succinic acid.[32]

Class Ic is mainly based on enantio-labdatrienonic acids, such as ozic and zanzibaric acids.[32] Its most familiar representative is Dominican amber,.[31] which is mostly transparent and often contains a higher number of fossil inclusions. This has enabled the detailed reconstruction of the ecosystem of a long-vanished tropical forest.[36] Resin from the extinct species Hymenaea protera is the source of Dominican amber and probably of most amber found in the tropics. It is not "succinite" but "retinite".[37]

الدرجة 2

These ambers are formed from resins with a sesquiterpenoid base, such as cadinene.[32]

الدرجة 3

These ambers are polystyrenes.[32]

الدرجة 4

Class IV is something of a catch-all: its ambers are not polymerized, but mainly consist of cedrene-based sesquiterpenoids.[32]

الدرجة 5

Class V resins are considered to be produced by a pine or pine relative. They comprise a mixture of diterpinoid resins and n-alkyl compounds. Their main variety is Highgate copalite.[33]

السجل الجيولوجي

The oldest amber recovered dates to the late Carboniferous period ().[31][38] Its chemical composition makes it difficult to match the amber to its producers – it is most similar to the resins produced by flowering plants; however, the first flowering plants appeared in the Early Cretaceous, about 200 million years after the oldest amber known to date, and they were not common until the Late Cretaceous. Amber becomes abundant long after the Carboniferous, in the Early Cretaceous,[31] when it is found in association with insects. The oldest amber with arthropod inclusions comes from the Late Triassic (late Carnian ح. 230 Ma) of Italy, where four microscopic (0.2–0.1 mm) mites, Triasacarus, Ampezzoa, Minyacarus and Cheirolepidoptus, and a poorly preserved nematoceran fly were found in millimetre-sized droplets of amber.[39][40] The oldest amber with significant numbers of arthropod inclusions comes from Lebanon. This amber, referred to as Lebanese amber, is roughly 125–135 million years old, is considered of high scientific value, providing evidence of some of the oldest sampled ecosystems.[41]

In Lebanon, more than 450 outcrops of Lower Cretaceous amber were discovered by Dany Azar,[42] a Lebanese paleontologist and entomologist. Among these outcrops, 20 have yielded biological inclusions comprising the oldest representatives of several recent families of terrestrial arthropods. Even older Jurassic amber has been found recently in Lebanon as well. Many remarkable insects and spiders were recently discovered in the amber of Jordan including the oldest zorapterans, clerid beetles, umenocoleid roaches, and achiliid planthoppers.[41]

Burmese amber from the Hukawng Valley in northern Myanmar is the only commercially exploited Cretaceous amber. Uranium–lead dating of zircon crystals associated with the deposit have given an estimated depositional age of approximately 99 million years ago. Over 1,300 species have been described from the amber, with over 300 in 2019 alone.

Baltic amber is found as irregular nodules in marine glauconitic sand, known as blue earth, occurring in Upper Eocene strata of Sambia in Prussia.[14] It appears to have been partly derived from older Eocene deposits and it occurs also as a derivative phase in later formations, such as glacial drift. Relics of an abundant flora occur as inclusions trapped within the amber while the resin was yet fresh, suggesting relations with the flora of eastern Asia and the southern part of North America. Heinrich Göppert named the common amber-yielding pine of the Baltic forests Pinites succiniter, but as the wood does not seem to differ from that of the existing genus it has been also called Pinus succinifera. It is improbable that the production of amber was limited to a single species; and indeed a large number of conifers belonging to different genera are represented in the amber-flora.[19]

Paleontological significance

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| علم الإحاثة |

|---|

|

|

بوابة علم الإحاثة التصنيف |

Amber is a unique preservational mode, preserving otherwise unfossilizable parts of organisms; as such it is helpful in the reconstruction of ecosystems as well as organisms;[43] the chemical composition of the resin, however, is of limited utility in reconstructing the phylogenetic affinity of the resin producer.[31] Amber sometimes contains animals or plant matter that became caught in the resin as it was secreted. Insects, spiders and even their webs, annelids, frogs,[44] crustaceans, bacteria and amoebae,[45] marine microfossils,[46] wood, flowers and fruit, hair, feathers[47] and other small organisms have been recovered in Cretaceous ambers (deposited c. ).[31] There is even an ammonite Puzosia (Bhimaites) and marine gastropods found in Burmese amber.[48]

The preservation of prehistoric organisms in amber forms a key plot point in Michael Crichton's 1990 novel Jurassic Park and the 1993 movie adaptation by Steven Spielberg.[49] In the story, scientists are able to extract the preserved blood of dinosaurs from prehistoric mosquitoes trapped in amber, from which they genetically clone living dinosaurs. Scientifically this is as yet impossible, since no amber with fossilized mosquitoes has ever yielded preserved blood.[50] Amber is, however, conducive to preserving DNA, since it dehydrates and thus stabilizes organisms trapped inside. One projection in 1999 estimated that DNA trapped in amber could last up to 100 million years, far beyond most estimates of around 1 million years in the most ideal conditions,[51] although a later 2013 study was unable to extract DNA from insects trapped in much more recent Holocene copal.[52] In 1938, 12-year-old David Attenborough (brother of Richard who played John Hammond in Jurassic Park) was given a piece of amber containing prehistoric creatures from his adoptive sister; it would be the focus of his 2004 BBC documentary The Amber Time Machine.[53]

الاستخدامات

المجوهرات

Amber has been used as jewelry since the Stone Age, from 13,000 years ago.[31] Amber ornaments have been found in Mycenaean tombs and elsewhere across Europe.[54] To this day it is used in the manufacture of smoking and glassblowing mouthpieces.[55][56] Amber's place in culture and tradition lends it a tourism value; Palanga Amber Museum is dedicated to the fossilized resin.[57]

استخدامات طبية تاريخية

Amber has long been used in folk medicine for its purported healing properties.[58] Amber and extracts were used from the time of Hippocrates in ancient Greece for a wide variety of treatments through the Middle Ages and up until the early twentieth century.[59]

Amber necklaces are a traditional European remedy for colic or teething pain with purported analgesic properties of succinic acid, although there is no evidence that this is an effective remedy or delivery method.[58][60][61] The American Academy of Pediatrics and the FDA have warned strongly against their use, as they present both a choking and a strangulation hazard.[60][62]

رائحة العنبر والعنبر العطري

In ancient China, it was customary to burn amber during large festivities. If amber is heated under the right conditions, oil of amber is produced, and in past times this was combined carefully with nitric acid to create "artificial musk" – a resin with a peculiar musky odor.[63] Although when burned, amber does give off a characteristic "pinewood" fragrance, modern products, such as perfume, do not normally use actual amber because fossilized amber produces very little scent. In perfumery, scents referred to as "amber" are often created and patented[64][65] to emulate the opulent golden warmth of the fossil.[66]

The scent of amber was originally derived from emulating the scent of ambergris and/or the plant resin labdanum, but since sperm whales are endangered, the scent of amber is now largely derived from labdanum.[67] The term "amber" is loosely used to describe a scent that is warm, musky, rich and honey-like, and also somewhat earthy. Benzoin is usually part of the recipe. Vanilla and cloves are sometimes used to enhance the aroma. "Amber" perfumes may be created using combinations of labdanum, benzoin resin, copal (a type of tree resin used in incense manufacture), vanilla, Dammara resin and/or synthetic materials.[63]

In Arab Muslim tradition, popular scents include amber, jasmine, musk and oud (agarwood).[68]

مواد التقليد

Young resins used as imitations:[69]

- Kauri resin from Agathis australis trees in New Zealand.

- The copals (subfossil resins). The African and American (Colombia) copals from Leguminosae trees family (genus Hymenaea). Amber of the Dominican or Mexican type (Class I of fossil resins). Copals from Manilia (Indonesia) and from New Zealand from trees of the genus Agathis (family Araucariaceae)

- Other fossil resins: burmite in Burma, rumenite in Romania, and simetite in Sicily.

- Other natural resins — cellulose or chitin, etc.

Plastics used as imitations:[70]

- Stained glass (inorganic material) and other ceramic materials

- Celluloid

- Cellulose nitrate (first obtained in 1833[71]) — a product of treatment of cellulose with nitration mixture.[72]

- Acetylcellulose (not in the use at present)

- Galalith or "artificial horn" (condensation product of casein and formaldehyde), other trade names: Alladinite, Erinoid, Lactoid.[71]

- Casein — a conjugated protein forming from the casein precursor – caseinogen.[73]

- Resolane (phenolic resins or phenoplasts, not in the use at present)

- Bakelite resine (resol, phenolic resins), product from Africa are known under the misleading name "African amber".

- Carbamide resins — melamine, formaldehyde and urea-formaldehyde resins.[72]

- Epoxy novolac (phenolic resins), unofficial name "antique amber", not in the use at present

- Polyesters (Polish amber imitation) with styrene. For example, unsaturated polyester resins (polymals) are produced by Chemical Industrial Works "Organika" in Sarzyna, Poland; estomal are produced by Laminopol firm. Polybern or sticked amber is artificial resins the curled chips are obtained, whereas in the case of amber – small scraps. "African amber" (polyester, synacryl is then probably other name of the same resine) are produced by Reichhold firm; Styresol trade mark or alkid resin (used in Russia, Reichhold, Inc. patent, 1948.[74]

- Polyethylene

- Epoxy resins

- Polystyrene and polystyrene-like polymers (vinyl polymers).[75]

- The resins of acrylic type (vinyl polymers[75]), especially polymethyl methacrylate PMMA (trade mark Plexiglass, metaplex).

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

المصادر

- ^ Jessamyn Reeves-Brown (November 1997). "Mastering New Materials: Commissioning an Amber Bow". Strings (65). Archived from the original on 14 May 2004. Retrieved 9 April 2007.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|journal= - ^ كهربا - لغت نامه دهخدا

- ^ سید مرتضی مهدوی نصر : تحلیل وریشه شناسی واژه "کهرمان" (قهرمان) - لغت نامه دهخدا

- ^ Natural History 37.11 Archived 24 سبتمبر 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854), MENTONOMON". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2025-04-22.

- ^ Natural History IV.27.13 or IV.13.95 in the Loeb edition.

- ^ Beck, Curt W. (1966-09-01). "Analysis and Provenience of Minoan and Mycenaean Amber, I". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 7 (3): 191–211.

- ^ Compare succinic acid as well as succinite, a term given to a particular type of amber by James Dwight Dana

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Natural History. p. Book 37.XI.

- ^ Mikanowski, Jacob (2022). Goodbye, Eastern Europe: An Intimate History of a Divided Land. New York: Pantheon Books. p. 4. ISBN 9781524748500.

- ^ Chen, Dian; Zeng, Qingshuo; Yuan, Ye; Cui, Benxin; Luo, Wugan (November 2019). "Baltic amber or Burmese amber: FTIR studies on amber artifacts of Eastern Han Dynasty unearthed from Nanyang". Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy (in الإنجليزية). 222: 117270. Bibcode:2019AcSpA.22217270C. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2019.117270. PMID 31226615. S2CID 195261188.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةJersey - ^ أ ب ت Anderson, L.A. (2023). "A chemical framework for the preservation of fossil vertebrate cells and soft tissues". Earth-Science Reviews. 240: 104367. Bibcode:2023ESRv..24004367A. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104367. S2CID 257326012.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Rudler 1911, p. 792.

- ^ Manuel Villanueva-García, Antonio Martínez-Richa, and Juvencio Robles Assignment of vibrational spectra of labdatriene derivatives and ambers: A combined experimental and density functional theoretical study Archived 12 أبريل 2006 at the Wayback Machine Arkivoc (EJ-1567C) pp. 449–458

- ^ Moldoveanu, S.C. (1998). Analytical pyrolysis of natural organic polymers. Elsevier.

- ^ Poinar, George O.; Poinar, Hendrik N.; Cano, Raul J. (1994). "DNA from Amber Inclusions". Ancient DNA. New York, NY: Springer New York. pp. 92–103. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-4318-2_6. ISBN 978-0-387-94308-4.

- ^ Braswell-Tripp, Pearlie (2013). Real Diamonds & Precious Stones of the Bible (in الإنجليزية). Bloomington: Xlibris Corporation. p. 70. ISBN 9781479796441.

- ^ أ ب ت Rudler 1911, p. 793.

- ^ Poinar, George O. (1992). Life in Amber. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 9.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (1 April 2008). "BBC News, " Secret 'dino bugs' revealed", 1 April 2008". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 August 2010.

- ^ Rice, Patty C. (2006). Amber: Golden Gem of the Ages. 4th Ed. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4259-3849-9.

- ^ Poinar, George O. (1992) Life in amber. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, p. 12, ISBN 0804720010

- ^ Lambert, JB; Poinar, GO Jr. (2002). "Amber: the organic gemstone". Accounts of Chemical Research. 35 (8): 628–36. doi:10.1021/ar0001970. PMID 12186567.

- ^ Wolfe, A. P.; Tappert, R.; Muehlenbachs, K.; Boudreau, M.; McKellar, R. C.; Basinger, J. F.; Garrett, A. (30 June 2009). "A new proposal concerning the botanical origin of Baltic amber". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1672): 3403–3412. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0806. PMC 2817186. PMID 19570786.

- ^ Sherborn, Charles Davies (1892). "Natural Science: A Monthly Review of Scientific Progress, Volume 1".

- ^ "Amber: Natural Organic Amber Gemstone & Jewelry Information; GemSelect". www.gemselect.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةelectric - ^ "Amber". (1999). In G. W. Bowersock, Peter Brown, Oleg Grabar (eds.) Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0674511735.

- ^ Manuel A. Iturralde-Vennet (2001). "Geology of the Amber-Bearing Deposits of the Greater Antilles" (PDF). Caribbean Journal of Science. 37 (3): 141–167. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Grimaldi, D. (2009). "Pushing Back Amber Production". Science. 326 (5949): 51–2. Bibcode:2009Sci...326...51G. doi:10.1126/science.1179328. PMID 19797645. S2CID 206522565.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Anderson, K; Winans, R; Botto, R (1992). "The nature and fate of natural resins in the geosphere—II. Identification, classification and nomenclature of resinites". Organic Geochemistry. 18 (6): 829–841. Bibcode:1992OrGeo..18..829A. doi:10.1016/0146-6380(92)90051-X.

- ^ أ ب ت Anderson, K; Botto, R (1993). "The nature and fate of natural resins in the geosphere—III. Re-evaluation of the structure and composition of Highgate Copalite and Glessite". Organic Geochemistry. 20 (7): 1027. Bibcode:1993OrGeo..20.1027A. doi:10.1016/0146-6380(93)90111-N.

- ^ Anderson, Ken B. (1996). "New Evidence Concerning the Structure, Composition, and Maturation of Class I (Polylabdanoid) Resinites". Amber, Resinite, and Fossil Resins. ACS Symposium Series. Vol. 617. pp. 105–129. doi:10.1021/bk-1995-0617.ch006. ISBN 978-0-8412-3336-2.

- ^ Shashoua, Yvonne (2007). "Degradation and inhibitive conservation of Baltic amber in museum collections" (PDF). Department of Conservation, The National Museum of Denmark. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011.

- ^ George Poinar, Jr. and Roberta Poinar, 1999. The Amber Forest: A Reconstruction of a Vanished World, (Princeton University Press) ISBN 0-691-02888-5

- ^ Grimaldi, D. A. (1996) Amber – Window to the Past. – American Museum of Natural History, New York, ISBN 0810919664

- ^ Bray, P. S.; Anderson, K. B. (2009). "Identification of Carboniferous (320 Million Years Old) Class Ic Amber". Science. 326 (5949): 132–134. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..132B. doi:10.1126/science.1177539. PMID 19797659. S2CID 128461248.

- ^ Schmidt, A. R.; Jancke, S.; Lindquist, E. E.; Ragazzi, E.; Roghi, G.; Nascimbene, P. C.; Schmidt, K.; Wappler, T.; Grimaldi, D. A. (2012). "Arthropods in amber from the Triassic Period". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (37): 14796–801. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10914796S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208464109. PMC 3443139. PMID 22927387.

- ^ Sidorchuk, Ekaterina A.; Schmidt, Alexander R.; Ragazzi, Eugenio; Roghi, Guido; Lindquist, Evert E. (February 2015). "Plant-feeding mite diversity in Triassic amber (Acari: Tetrapodili)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology (in الإنجليزية). 13 (2): 129–151. Bibcode:2015JSPal..13..129S. doi:10.1080/14772019.2013.867373. ISSN 1477-2019. S2CID 85055941.

- ^ أ ب Poinar, P.O., Jr., and R.K. Milki (2001) Lebanese Amber: The Oldest Insect Ecosystem in Fossilized Resin. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis. ISBN 0-87071-533-X.

- ^ Azar, Dany (2012). "Lebanese amber: a "Guinness Book of Records"". Annales Universitatis Paedagogicae Cracoviensis. 111: 44–60.

- ^ BBC – Radio 4 – Amber Archived 12 فبراير 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Db.bbc.co.uk (16 February 2005). Retrieved on 23 April 2011.

- ^ "Scientist: Frog could be 25 million years old". NBC News. 16 February 2007.

- ^ Waggoner, Benjamin M. (13 July 1996). "Bacteria and protists from Middle Cretaceous amber of Ellsworth County, Kansas". PaleoBios. 17 (1): 20–26. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007.

- ^ Girard, V.; Schmidt, A.; Saint Martin, S.; Struwe, S.; Perrichot, V.; Saint Martin, J.; Grosheny, D.; Breton, G.; Néraudeau, D. (2008). "Evidence for marine microfossils from amber". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (45): 17426–17429. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10517426G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804980105. PMC 2582268. PMID 18981417.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةNYT-20161208 - ^ Dilcher, David; Wang, Bo; Zhang, Haichun; Xia, Fangyuan; Broly, Pierre; Kennedy, Jim; Ross, Andrew; Mu, Lin; Kelly, Richard (2019-05-10). "An ammonite trapped in Burmese amber". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (in الإنجليزية). 116 (23): 11345–11350. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11611345Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1821292116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6561253. PMID 31085633.

- ^ Don Shay & Jody Duncan (1993). The Making of Jurassic Park. p. 4.

- ^ Joseph Stromberg (2013-10-14). "A Fossilized Blood-Engorged Mosquito is Found for the First Time Ever". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2018-07-07.

- ^ J.L. Bada, X.S. Wang, H. Hamilton (1999). "Preservation of key biomolecules in the fossil record: Current knowledge and future challenges". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Vol. 354. pp. 77–87.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ News Staff. "Extracting Dinosaur DNA from Amber Fossils Impossible, Scientists Say". SciNews. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ "Jewel of the Earth". PBS. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Curt W. Beck, Anthony Harding and Helen Hughes-Brock, "Amber in the Mycenaean World" The Annual of the British School at Athens, vol. 69 (November 1974), pp. 145–172. DOI:10.1017/S0068245400005505 Archived 5 نوفمبر 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Interview with expert pipe maker, Baldo Baldi. Accessed 10-12-09". Pipesandtobaccos.com. 11 February 2000. Archived from the original on 16 February 2006.

- ^ "Maker of amber mouthpiece for glass blowing pipes. Accessed 10-12-09". Steinertindustries.com. 7 May 2007. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- ^ Schüler, C. J. (2022). Along the Amber Route: St. Petersburg to Venice (in الإنجليزية). Sandstone Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-912240-92-0.

With more than a quarter of a million pieces, this is thought to be the world's largest collection of amber

- ^ أ ب Lisa Markman (2009). "Teething: Facts and Fiction" (PDF). Pediatr. Rev. 30 (8): e59–e64. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.695.5675. doi:10.1542/pir.30-8-e59. PMID 19648257. S2CID 29522788. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2013.

- ^ Riddle, John M. (1973). "AMBER in ancient Pharmacy: The Transmission of Information About a Single Drug: A Case Study". Pharmacy in History. 15 (1): 3–17.

- ^ أ ب "Teething Necklaces and Beads: A Caution for Parents". HealthyChildren.org. 20 December 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- ^ "Amber Waves of Woo". Science-Based Medicine (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2014-04-11. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- ^ Health, Center for Devices and Radiological. "Safety Communications - FDA Warns Against Use of Teething Necklaces, Bracelets, and Other Jewelry Marketed for Relieving Teething Pain or Providing Sensory Stimulation: FDA Safety Communication". www.fda.gov (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- ^ أ ب "Amber as an aphrodisiac". Aphrodisiacs-info.com. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2012..

- ^ Thermer, Ernst T. "Saturated indane derivatives and processes for producing same" U.S. Patent 3٬703٬479, U.S. Patent 3٬681٬464, issue date 1972

- ^ Perfume compositions and perfume articles containing one isomer of an octahydrotetramethyl acetonaphthone, John B. Hall, Rumson; James Milton Sanders, Eatontown U.S. Patent 3٬929٬677, Publication Date: 30 December 1975

- ^ Sorcery of Scent: Amber: A perfume myth Archived 14 يناير 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Sorceryofscent.blogspot.com (30 July 2008). Retrieved on 23 April 2011.

- ^ Gomes, Paula B.; Mata, Vera G.; Rodrigues, A. E. (2005). "Characterization of the Portuguese-Grown Cistus ladanifer Essential Oil" (PDF). Journal of Essential Oil Research. 17 (2): 160–165. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.8772. doi:10.1080/10412905.2005.9698864. S2CID 96688538. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2012.

- ^ Auzias, Dominique; Labourdette, Jean-Paul (23 November 2022). QATAR (EN ANGLAIS) 2023/2024 Petit Futé. Petit Futé. ISBN 9782305096186.

- ^ Matushevskaya 2013, pp. 11–13

- ^ Matushevskaya 2013, pp. 13–19

- ^ أ ب Wagner-Wysiecka 2013, p. 30

- ^ أ ب Bogdasarov & Bogdasarov 2013, p. 38

- ^ Bogdasarov & Bogdasarov 2013, p. 37

- ^ Wagner-Wysiecka 2013, p. 31

- ^ أ ب Wagner-Wysiecka 2013, p. 32

- المراجع

- تحوي هذه المقالة معلومات مترجمة من الطبعة الحادية عشرة لدائرة المعارف البريطانية لسنة 1911 وهي الآن من ضمن الملكية العامة.

وصلات خارجية

- Farlang many full text historical references on Amber Theophrastus, George Frederick Kunz, and special on Baltic amber.

- IPS Publications on amber inclusions International Paleoentomological Society: Scientific Articles on amber and its inclusions

- Webmineral on Amber Physical properties and mineralogical information

- Mindat Amber Image and locality information on amber

- NY Times 40 million year old extinct bee in Dominican amber

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2018

- All Wikipedia articles needing clarification

- Wikipedia articles needing clarification from March 2023

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2021

- مقالات مأخوذة من الطبعة الحادية عشرة لدائرة المعارف البريطانية

- Fossil resins

- أحجار كريمة

- مواد صلبة غير بلورية

- الطب الشعبي