جنون البقر

| Bovine spongiform encephalopathy | |

|---|---|

| الأسماء الأخرى | Mad cow disease |

| |

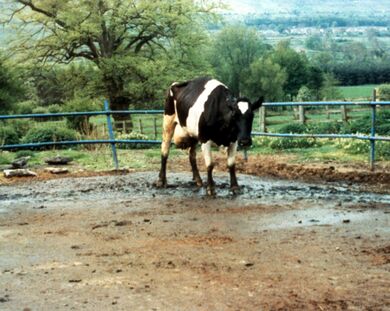

| A cow with BSE | |

| التخصص | Neurology, veterinary medicine |

| الأعراض | Abnormal behavior, trouble walking, weight loss, inability to move[1] |

| المضاعفات | Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (if BSE-infected beef is eaten by humans) |

| البداية المعتادة | 4–5 years after exposure[2] |

| الأنواع | Classic, atypical[1] |

| المسببات | A type of prion[3] |

| عوامل الخطر | Feeding contaminated meat and bone meal to cattle |

| الطريقة التشخيصية | Suspected based on symptoms, confirmed by examination of the brain[1] |

| الوقاية | Not allowing sick or older animals to enter the food supply, disallowing certain products in animal food[4] |

| العلاج | None |

| Prognosis | Death within weeks to months[2] |

| التردد | 4 reported cases (2017)[1] [3] اعتبارا من 2024[تحديث], a total of 233 cases of vCJD had been reported globally.[5] |

اعتلال الدماخ الإسفنجي البقري Bovine spongiform encephalopathy أو مرض جنون البقر mad cow disease هو مرض تنكسي عصبي قاتل لا شفاء منه يصيب الأبقار.[2] الأعراض تضم سلوك شاذ، صعوبة في المشي، وفقدان الوزن.[1] وفي مراحل لاحقة من المرض، تصبح البقرة غير قادرة على العمل بشكل طبيعي.[1] هناك معلومات متضاربة حول الوقت بين العدوى وبدء الأعراض. في 2002، اقترحت منظمة الصحة العالمية أنه يناهز أربع لخمس سنوات.[2] الوقت من بدء الأعراض إلى الوفاة يقاس عموماً بالأسابيع إلى شهور.[2] الانتشار إلى البشر يُعتقد أنه نتبجة مرض كرويتسفلت-جاكوب المتغير (vCJD).[3] اعتبارا من 2024[تحديث]، أفيد بوجود 233 حالة من vCJD حول العالم.[5]

BSE is thought to be due to an infection by a misfolded protein, known as a prion.[3][6] Cattle are believed to have been infected by being fed meat-and-bone meal that contained either the remains of cattle who spontaneously developed the disease or scrapie-infected sheep products.[3][7] The United Kingdom was afflicted with an outbreak of BSE and vCJD in the 1980s and 1990s. The outbreak increased throughout the UK due to the practice of feeding meat-and-bone meal to young calves of dairy cows.[3][8] Cases are suspected based on symptoms and confirmed by examination of the brain.[1] Cases are classified as classic or atypical, with the latter divided into H- and L types.[1] It is a type of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy.[9]

Efforts to prevent the disease in the UK include not allowing any animal older than 30 months to enter either the human food or animal feed supply.[4] In continental Europe, cattle over 30 months must be tested if they are intended for human food.[4] In North America, tissue of concern, known as specified risk material, may not be added to animal feed or pet food.[10] About four million cows were killed during the eradication programme in the UK.[11]

Four cases were reported globally in 2017, and the condition is considered to be nearly eradicated.[1] In the United Kingdom, more than 184,000 cattle were diagnosed from 1986 to 2015, with the peak of new cases occurring in 1993.[3] A few thousand additional cases have been reported in other regions of the world.[1] In addition, it is believed that several million cattle with the condition likely entered the food supply during the outbreak.[1]

شُخَّص هذا المرض أول مرة في المملكة المتحدة عام 1986م، إلا أن الدلائل تشير إلى ظهور أول حالة في أبريل 1985م. ويعتقد العلماء أن إطعام الأبقار بالمنتجات الحيوانية المصابة قد سبب هذا المرض. وفي أواخر الثمانينيات بدأت البحوث لاكتشاف كيفية انتشار العدوى بين الحيوانات.

وفي عام 1990م ظهرت في المملكة المتحدة مخاوف من تسرب لحوم الأبقار المصابة إلى طعام البشر. وأدت هذه المخاوف إلى تناقص مبيعات اللحوم المنتجة محليًا بنسبة 20%. وبالإضافة إلى ذلك وضعت أكثر من عشرين دولة قيودًا على استيراد اللحوم والأبقار الحية من المملكة المتحدة.

لم يتفق العلماء حول مدى تأثير أكل لحوم الأبقار المصابة على الإنسان. فمعظمهم يعتقد أن الحيوانات المذبوحة والمقطوعة جيدًا لا ضرر منها إذا ثبت بالفحص خلوها من المرض. وتستبعد أمعاء الحيوان ودماغه ونخاعه الشوكي فلا تؤكل. أما الحيوان الذي تثبت إصابته فإنه يذبح ويتم التخلص من جثته تمامًا. وفي عام 1996م، اكتشف العلماء دلائل تشير إلى وجود علاقة بين مرض جنون البقر ومرض كرويتسفلت-جاكوب الذي يصيب الإنسان. ورغم أن الحكومة البريطانية قد قللت من مخاطر مرض جنون البقر على الإنسان إلا أن دولاً كثيرة امتنعت عن استيراد اللحوم البريطانية. وبدأت الحكومة البريطانية برنامجًا للتخلص من الأبقار المصابة بذبحها، وذلك لاستئصال المرض.

العلامات

Signs are not seen immediately in cattle, due to the disease's extremely long incubation period.[12] Some cattle have been observed to have an abnormal gait, changes in behavior, tremors and hyper-responsiveness to certain stimuli.[13] Hindlimb ataxia affects the animal's gait and occurs when muscle control is lost. This results in poor balance and coordination.[14] Behavioural changes may include aggression, anxiety relating to certain situations, nervousness, frenzy and an overall change in temperament. Some rare but previously observed signs also include persistent pacing, rubbing and licking. Additionally, nonspecific signs have also been observed which include weight loss, decreased milk production, lameness, ear infections and teeth grinding due to pain. Some animals may show a combination of these signs, while others may only be observed demonstrating one of the many reported. Once clinical signs arise, they typically get worse over the subsequent weeks and months, eventually leading to recumbency, coma and death.[13]

الأسباب

BSE is an infectious disease believed to be due to a misfolded protein, known as a prion.[3][6] Cattle are believed to have been infected from being fed meat and bone meal that contained the remains of other cattle who spontaneously developed the disease or scrapie-infected sheep products.[3] The outbreak increased throughout the United Kingdom due to the practice of feeding meat-and-bone meal to young calves of dairy cows.[3][8]

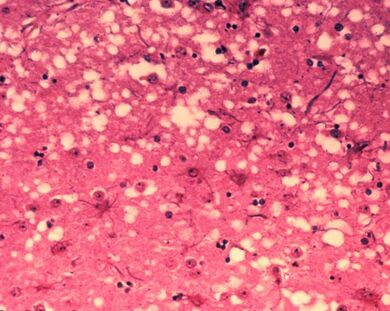

BSE prions are misfolded forms of the particular brain protein called prion protein. When this protein is misfolded, the normal alpha-helical structure is converted into a beta sheet. The prion induces normally-folded proteins to take on the misfolded phenotype in an exponential cascade. These sheets form small chains which aggregate and cause cell death. Massive cell death forms lesions in the brain which lead to degeneration of physical and mental abilities and ultimately death.[15] The prion is not destroyed even if the beef or material containing it is cooked or heat-treated under normal conditions and pressures.[16] Transmission can occur when healthy animals come in contact with tainted tissues from others with the disease, generally when their food source contains tainted meat.[2]

The British Government enquiry took the view that the cause was not scrapie, as had originally been postulated, but was some event in the 1970s that could not be identified.[17]

الانتشار إلى البشر

Spread to humans is believed to result in variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD).[3] The agent can be transmitted to humans by eating food contaminated with it.[18] Though any tissue may be involved, the highest risk to humans is believed to be from eating food contaminated with the brain, spinal cord, or digestive tract.[19][20] Despite the lack of knowledge on potential factors triggering the misfolded protein forms, idiopathic prion disorders are the most prevalent, accounting for 85–90% of human cases.[21]

تطور المرض

The pathogenesis of BSE is not well understood or documented like other diseases of this nature. Even though BSE is a disease that results in neurological defects, its pathogenesis occurs in areas that reside outside of the nervous system.[22] There was a strong deposition of PrPSc initially located in the ileal Peyer's patches of the small intestine.[23] The lymphatic system has been identified in the pathogenesis of scrapie. It has not, however, been determined to be an essential part of the pathogenesis of BSE. The Ileal Peyer's patches have been the only organ from this system that has been found to play a major role in the pathogenesis.[22] Infectivity of the Ileal Peyer's patches has been observed as early as four months after inoculation.[23] PrPSc accumulation was found to occur mostly in tangible body macrophages of the Ileal Peyer's patches. Tangible body macrophages involved in PrPSc clearance are thought to play a role in PrPSc accumulation in the Peyer's patches. Accumulation of PrPSc was also found in follicular dendritic cells, to a lesser degree.[24] Six months after inoculation, there was no infectivity in any tissues, only that of the ileum. This led researchers to believe that the disease agent replicates here. In naturally confirmed cases, there have been no reports of infectivity in the Ileal Peyer's patches. Generally, in clinical experiments, high doses of the disease are administered. In natural cases, it was hypothesized that low doses of the agent were present, and therefore, infectivity could not be observed.[25]

التشخيص

Diagnosis of BSE continues to be a practical problem. It has an incubation period of months to years, during which no signs are noticed, though the pathway of converting the normal brain prion protein (PrP) into the toxic, disease-related PrPSc form has started. At present, no way is known to detect PrPSc reliably except by examining post mortem brain tissue using neuropathological and immunohistochemical methods. Accumulation of the abnormally folded PrPSc form of PrP is a characteristic of the disease, but it is present at very low levels in easily accessible body fluids such as blood or urine. Researchers have tried to develop methods to measure PrPSc, but no methods for use in materials such as blood have been accepted fully.

The traditional method of diagnosis relies on histopathological examination of the medulla oblongata of the brain, and other tissues, post mortem. Immunohistochemistry can be used to demonstrate prion protein accumulation.[26]

In 2010, a team from New York described detection of PrPSc even when initially present at only one part in a hundred billion (10−11) in brain tissue. The method combines amplification with a novel technology called surround optical fiber immunoassay and some specific antibodies against PrPSc. After amplifying and then concentrating any PrPSc, the samples are labelled with a fluorescent dye using an antibody for specificity and then finally loaded into a microcapillary tube. This tube is placed in a specially constructed apparatus so it is totally surrounded by optical fibres to capture all light emitted once the dye is excited using a laser. The technique allowed detection of PrPSc after many fewer cycles of conversion than others have achieved, substantially reducing the possibility of artifacts, as well as speeding up the assay. The researchers also tested their method on blood samples from apparently healthy sheep that went on to develop scrapie. The animals' brains were analysed once any signs became apparent. The researchers could, therefore, compare results from brain tissue and blood taken once the animals exhibited signs of the diseases, with blood obtained earlier in the animals' lives, and from uninfected animals. The results showed very clearly that PrPSc could be detected in the blood of animals long before the signs appeared. After further development and testing, this method could be of great value in surveillance as a blood- or urine-based screening test for BSE.[27][28]

التصنيف

BSE is a transmissible disease that primarily affects the central nervous system; it is a form of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy, like Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and kuru in humans, scrapie in sheep, and chronic wasting disease in deer.[18][29][30]

الوقاية

A ban on feeding meat and bone meal to cattle has resulted in a strong reduction in cases in countries where the disease has been present. In disease-free countries, control relies on import control, feeding regulations, and surveillance measures.[26]

In UK and US slaughterhouses, the brain, spinal cord, trigeminal ganglia, intestines, eyes, and tonsils from cattle are classified as specified risk materials, and must be disposed of appropriately.[26]

An enhanced BSE-related feed ban was enacted in both the United States (2009) and Canada (2007) to help improve prevention and elimination of BSE.[31]

الوبائيات

The tests used for detecting BSE vary considerably, as do the regulations in various jurisdictions for when, and which cattle, must be tested. For instance in the EU, the cattle tested are older (30 months or older), while many cattle are slaughtered younger than that. At the opposite end of the scale, Japan tests all cattle at the time of slaughter. Tests are also difficult, as the altered prion protein has very low levels in blood or urine, and no other signal has been found. Newer tests[حدد] are faster, more sensitive, and cheaper, so future figures possibly may be more comprehensive. Even so, currently the only reliable test is examination of tissues during a necropsy.[citation needed]

As for vCJD in humans, autopsy tests are not always done, so those figures, too, are likely to be too low, but probably by a lesser fraction. In the United Kingdom, anyone with possible vCJD symptoms must be reported to the Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease Surveillance Unit. In the United States, the CDC has refused to impose a national requirement that physicians and hospitals report cases of the disease. Instead, the agency relies on other methods, including death certificates and urging physicians to send suspicious cases to the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, which is funded by the CDC.

To control potential transmission of vCJD within the United States, the FDA had established strict restrictions on individuals' eligibility to donate blood. Individuals who had spent a cumulative time of three months or more in the United Kingdom between 1980 and 1996, or a cumulative time of five years or more from 1980 to 2020 in any combination of countries in Europe, were prohibited from donating blood.[32] Due to blood shortages associated with the 2020 COVID-19 outbreak these restrictions were temporarily rescinded in 2020.[33] This recommendation was removed in 2022.[34]

Similar rules also apply in Germany[35] and formerly Australia.[36] Anyone who lived in the UK between 1980 and 1996 for longer than six months is prohibited from giving blood.[35] There are also prohibitions on donating breast milk and tissue.[37] However, there are no restrictions on organ donation.[38] Blood donation organisations first considered relaxing the rules after the COVID-19 pandemic and some natural disasters that depleted the blood supply.[39]

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز Casalone C, Hope J (2018). "Atypical and classic bovine spongiform encephalopathy". Human Prion Diseases. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 153. Elsevier. pp. 121–134. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-63945-5.00007-6. ISBN 9780444639455. PMID 29887132.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح "Bovine spongiform encephalopathy". WHO. November 2002. Archived from the original on 2012-12-18. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز "About BSE BSE (Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy) Prion Diseases". CDC (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2 October 2018. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت "Control Measures BSE (Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy) Prion Diseases". CDC (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2 October 2018. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ^ أ ب "About Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD)". CDC (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 14 March 2024. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ أ ب "Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) Questions and Answers". FDA (in الإنجليزية). 22 May 2019. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ Prusiner SB (May 2001). "Shattuck lecture--neurodegenerative diseases and prions". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (20): 1516–26. doi:10.1056/NEJM200105173442006. PMID 11357156.

- ^ أ ب Nathanson N, Wilesmith J, Griot C (June 1997). "Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE): causes and consequences of a common source epidemic". American Journal of Epidemiology. 145 (11): 959–69. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009064. PMID 9169904.

- ^ "Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE)". WHO. Archived from the original on 9 March 2005. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Feed Bans BSE (Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy) | Prion Diseases". CDC (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2 October 2018. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ^ "'All steps taken' after BSE diagnosis". BBC News. 23 October 2018. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ^ Thomson G. "Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ أ ب "Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy" (PDF). The Center for Food Security & Public Health. August 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ^ "Ataxias and Cerebellar or Spinocerebellar Degeneration Information Page: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)". www.ninds.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- ^ Orge L, Lima C, Machado C, Tavares P, Mendonça P, Carvalho P, et al. (March 2021). "Neuropathology of Animal Prion Diseases". Biomolecules. 11 (3): 466. doi:10.3390/biom11030466. PMC 8004141. PMID 33801117.

- ^ "Bovine Spongiform Encephalopaphy: An Overview" (PDF). Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, United States Department of Agriculture. ديسمبر 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- ^ "Vol.1 - Executive Summary of the Report of the Inquiry". webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2009-05-05.

- ^ أ ب Budka H, Will RG (12 November 2015). "The end of the BSE saga: do we still need surveillance for human prion diseases?". Swiss Medical Weekly. 145: w14212. doi:10.4414/smw.2015.14212. PMID 26715203.

- ^ "Commonly Asked Questions About BSE in Products Regulated by FDA's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN)". Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Food and Drug Administration. 14 سبتمبر 2005. Archived from the original on 9 مايو 2008. Retrieved 8 أبريل 2008.

- ^ Ramasamy I, Law M, Collins S, Brooke F (April 2003). "Organ distribution of prion proteins in variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 3 (4): 214–22. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00578-4. PMID 12679264.

- ^ "Department of Health and Human Services CfDCaP. Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, Classic (CJD). Occurrence and Transmission (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022)". 14 November 2022.

- ^ أ ب Espinosa JC, Morales M, Castilla J, Rogers M, Torres JM (April 2007). "Progression of prion infectivity in asymptomatic cattle after oral bovine spongiform encephalopathy challenge". The Journal of General Virology. 88 (Pt 4): 1379–83. doi:10.1099/vir.0.82647-0. PMID 17374785.

- ^ أ ب Balkema-Buschmann A, Fast C, Kaatz M, Eiden M, Ziegler U, McIntyre L, et al. (November 2011). "Pathogenesis of classical and atypical BSE in cattle". Preventive Veterinary Medicine. Special Issue: Animal Health in the 21st Century – A Global ChallengeAnimal Health in the 21st Century. 102 (2): 112–7. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2011.04.006. PMID 21592603.

- ^ Hoffmann C, Ziegler U, Buschmann A, Weber A, Kupfer L, Oelschlegel A, et al. (March 2007). "Prions spread via the autonomic nervous system from the gut to the central nervous system in cattle incubating bovine spongiform encephalopathy". The Journal of General Virology. 88 (Pt 3): 1048–55. doi:10.1099/vir.0.82186-0. PMID 17325380.

- ^ Wells GA, Hawkins SA, Green RB, Austin AR, Dexter I, Spencer YI, et al. (January 1998). "Preliminary observations on the pathogenesis of experimental bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE): an update". The Veterinary Record. 142 (5): 103–6. doi:10.1136/vr.142.5.103. PMID 9501384. S2CID 84765420. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ أ ب ت "Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy". WikiVet. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ "Detecting Prions in Blood" (PDF). Microbiology Today: 195. August 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ "SOFIA: An Assay Platform for Ultrasensitive Detection of PrPSc in Brain and Blood" (PDF). SUNY Downstate Medical Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ Eraña H, Venegas V, Moreno J, Castilla J (February 2017). "Prion-like disorders and Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies: An overview of the mechanistic features that are shared by the various disease-related misfolded proteins". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 483 (4): 1125–1136. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.166. PMID 27590581. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ Waddell L, Greig J, Mascarenhas M, Otten A, Corrin T, Hierlihy K (February 2018). "Current evidence on the transmissibility of chronic wasting disease prions to humans-A systematic review". Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 65 (1): 37–49. doi:10.1111/tbed.12612. PMID 28139079.

- ^ "Feed Bans BSE (Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy) | Prion Diseases | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ^ Eligibility Criteria for Blood Donation Archived 27 يناير 2018 at the Wayback Machine, American Red Cross

- ^ FDA Provides Updated Guidance Addressing Urgent Need For Blood During The Pandemic Archived 7 أغسطس 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Food and Drug Administration

- ^ Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and (2022-05-24). "Recommendations to Reduce the Possible Risk of Transmission of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease and Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease by Blood and Blood Components". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-04-01.

- ^ أ ب "Richtlinie zur Gewinnung von Blut und Blutbestandteilen und zur Anwendung von Blutprodukten (Richtlinie Hämotherapie)" (PDF). 2017-02-17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-06-28. Retrieved 2023-04-01.

- ^ "I lived in the UK for six months between 1980-96. Can I donate blood? | Lifeblood". www.lifeblood.com.au (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ^ "'Mad cow disease' - why you can't donate blood, breast milk and tissues". Queensland Health (in الإنجليزية الأسترالية). 4 April 2018. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ^ "More information about donating blood if you have lived in the UK | Australian Red Cross Lifeblood". www.donateblood.com.au. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ^ "Australian blood bank reconsidering ban on UK donations from 'mad cow disease' era". the Guardian (in الإنجليزية). Australian Associated Press. 2021-04-20. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

وصلات خارجية

- World Organisation for Animal Health: BSE situation in the world and annual incidence rate

- UK BSE Inquiry Website, Archived at The National Archives

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأسترالية-language sources (en-au)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 2024

- جميع المقالات التي فيها عبارات متقادمة

- Articles needing more detailed references

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2020

- Bovine diseases

- Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies

- Infectious diseases with eradication efforts

- Foodborne illnesses

- Health disasters

- Food safety in the European Union

- Wikipedia medicine articles ready to translate

- Health disasters in the United Kingdom