يان سموتس

يان كريستيان سموتس | |

|---|---|

Jan Christiaan Smuts | |

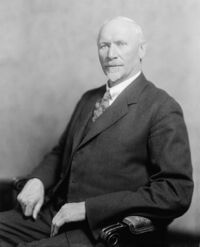

Smuts in 1934 | |

| الرابع رئيس وزراء جنوب أفريقيا | |

| في المنصب 5 سبتمبر 1939 – 4 يونيو 1948 | |

| العاهل | جورج السادس |

| Governor-General | پاتريك دنكان Nicolaas Jacobus de Wet (مؤقت) Gideon Brand van Zyl |

| سبقه | James Barry Munnik Hertzog |

| خلـَفه | دانيال فرانسوا مالان |

| الثاني رئيس وزراء جنوب أفريقيا | |

| في المنصب 3 سبتمبر 1919 – 30 يونيو 1924 | |

| العاهل | جورج الخامس |

| Governor-General | The Earl of Buxton The Prince Arthur of Connaught The Earl of Athlone |

| سبقه | لويس بوتا |

| خلـَفه | James Barry Munnik Hertzog |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

| في المنصب 4 June 1948 – 11 September 1950 | |

| العاهل | George VI |

| رئيس الوزراء | Daniël Malan |

| سبقه | Daniël Malan |

| خلـَفه | Jacobus Strauss |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

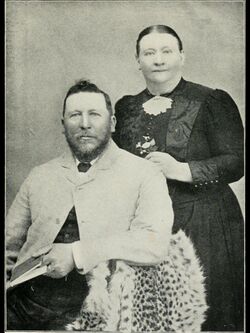

| وُلِد | 24 مايو 1870 بوڤنپلاتس، مستعمرة الكاپ |

| توفي | 11 سبتمبر 1950 (aged 80) دورنكلوف، أيرين، مقاطعة ترانسڤال، اتحاد جنوب أفريقيا |

| الحزب | |

| الزوج | Issie Krige |

| الأنجال | 6 |

| المدرسة الأم | |

| المهنة | Barrister |

| التوقيع |  |

| الخدمة العسكرية | |

| الولاء | South African Republic Union of South Africa United Kingdom |

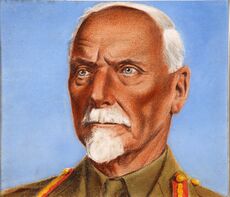

| الرتبة | Field Marshal |

| قاد | South African Defence Forces |

| المعارك/الحروب | Second Boer War First World War |

يان كريستيان سموتس ( Jan Christiaan Smuts ؛ OM, CH, DTD, ED, PC, KC, FRS؛ عاش 24 مايو 1870 – 11 سبتمبر 1950)، كان رجل دولة وقائد عسكري وفيلسوف في جنوب أفريقيا.[1] وبالإضافة لمناصبه العسكرية والإدارية، فقد تولى منصب رئيس وزراء اتحاد جنوب أفريقيا من 1919 إلى 1924 و 1939 إلى 1948.

Smuts was born to Afrikaner parents in the British Cape Colony. He was educated at Victoria College, Stellenbosch before reading law at Christ's College, Cambridge on a scholarship. He was called to the bar at the Middle Temple in 1894 but returned home the following year. In the leadup to the Second Boer War, Smuts practised law in Pretoria, the capital of the South African Republic. He led the republic's delegation to the Bloemfontein Conference and served as an officer in a commando unit following the outbreak of war in 1899. In 1902, he played a key role in negotiating the Treaty of Vereeniging, which ended the war and resulted in the annexation of the South African Republic and Orange Free State into the British Empire. He subsequently helped negotiate self-government for the Transvaal Colony, becoming a cabinet minister under Louis Botha.

Smuts played a leading role in the creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, helping shape its constitution. He and Botha established the South African Party, with Botha becoming the union's first prime minister and Smuts holding multiple cabinet portfolios. As defence minister he was responsible for the Union Defence Force during the First World War. Smuts personally led troops in the East African campaign in 1916 and the following year joined the Imperial War Cabinet in London. He played a leading role at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, advocating for the creation of the League of Nations and securing South African control over the former German South-West Africa.

In 1919, Smuts replaced Botha as prime minister, holding the office until the South African Party's defeat at the 1924 general election by J. B. M. Hertzog's National Party. He spent several years in academia, during which he coined the term "holism", before eventually re-entering politics as deputy prime minister in a coalition with Hertzog; in 1934 their parties subsequently merged to form the United Party. Smuts returned as prime minister in 1939, leading South Africa into the Second World War at the head of a pro-interventionist faction. He was appointed field marshal in 1941 and in 1945 signed the UN Charter, the only signer of the Treaty of Versailles to do so. His second term in office ended with the victory of his political opponents, the reconstituted National Party at the 1948 general election, with the new government implementing early apartheid policies.

Smuts was an internationalist who played a key role in establishing and defining the League of Nations, United Nations and Commonwealth of Nations. He supported racial segregation and opposed democratic non-racial rule. At the end of his career, Smuts supported the Fagan Commission's recommendations to relax restrictions on black South Africans living and working in urban areas.

النشأة والتعليم

ولد لعائلة غنية من المستعمرين البيض في جنوب إفريقيا في كيب تاون في 24 مارس عام 1870 وكان والده هولنديا. وكانت عائلته تمتلك مزرعة كبيرة في جنوب إفريقيا لكن الابن لم يكن مهتما بالزراعة ولا بإدارة شئون المزرعة مما أثار غضب والده. واتجه إلى دراسة القانون في إنجلترا ثم عاد إلى جنوب إفريقيا لينضم إلى الجيش في جنوب أفريقيا الذي فتح أمامه الباب لممارسة السياسة. وأصبح رئيساً لوزراء جنوب أفريقيا خلال الفترة من عام 1919 حتى عام 1924 ثم من عام 1939 حتى عام 1948.

السيرة

القانون والسياسة

اعتراف به من آدلر

Adler later wrote a letter, dated 31 January 1931, where he stated that he recommended Smuts's book to his students and followers. He referred to it as "the best preparation for the science of Individual Psychology".[2] After Smuts gave permission for the translation and publication of his book in Germany, it was translated by H. Minkowski and eventually published in 1938. During the Second World War, the books were destroyed after the Nazi government had removed it from circulation.[2] Adler and Smuts, however, continued their correspondence. In one of Adler’s letters dated 14 June 1931, he invited Smuts to be one of three judges of the best book on the history of wholeness with a reference to Individual Psychology.[2]

حرب البوير

Second World War

After nine years in opposition and academia, Smuts returned as deputy prime minister in a 'grand coalition' government under J. B. M. Hertzog. When Hertzog advocated neutrality towards Nazi Germany in 1939, the coalition split and Hertzog's motion to remain out of the war was defeated in Parliament by a vote of 80 to 67. Governor-General Sir Patrick Duncan refused Hertzog's request to dissolve parliament for a general election on the issue. Hertzog resigned and Duncan invited Smuts, Hertzog's coalition partner, to form a government and become prime minister for the second time in order to lead the country into the Second World War on the side of the Allies.[3]

On 24 May 1941, Smuts was appointed a field marshal of the British Army.[4]

Smuts's importance to the Imperial war effort was emphasised by a quite audacious plan, proposed as early as 1940, to appoint Smuts as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, should Churchill die or otherwise become incapacitated during the war. This idea was put forward by Sir John Colville, Churchill's private secretary, to Queen Mary and then to George VI, both of whom warmed to the idea.[5]

In May 1945, he represented South Africa in San Francisco at the drafting of the United Nations Charter.[6] According to historian Mark Mazower, Smuts "did more than anyone to argue for, and help draft, the UN's stirring preamble."[7] Smuts saw the UN as key to protecting white imperial rule over Africa.[8] Also in 1945, he was mentioned by Halvdan Koht among seven candidates that were qualified for the Nobel Prize in Peace. However, he did not explicitly nominate any of them. The person actually nominated was Cordell Hull.[9]

Later life

In domestic policy, a number of social security reforms were carried out during Smuts's second period in office as Prime Minister. Old-age pensions and disability grants were extended to 'Indians' and 'Africans' in 1944 and 1947 respectively, although there were differences in the level of grants paid out based on race. The Workmen's Compensation Act of 1941 "insured all employees irrespective of payment of the levy by employers and increased the number of diseases covered by the law," and the Unemployment Insurance Act of 1946 introduced unemployment insurance on a national scale, albeit with exclusions.[10]

Smuts continued to represent his country abroad. He was a leading guest at the 1947 wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. [11] At home, his preoccupation with the war had severe political repercussions in South Africa. Smuts's support of the war and his support for the Fagan Commission made him unpopular amongst the Afrikaner community and Daniel François Malan's pro-apartheid stance won the Reunited National Party the 1948 general election.[6]

In 1948, he was elected Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, becoming the first person from outside the United Kingdom to hold that position. He held the position until his death two years later.[12]

He accepted the appointment as Colonel-in-Chief of Regiment Westelike Provinsie as from 17 September 1948.[13]

In 1949, Smuts was bitterly opposed to the London Declaration which transformed British Commonwealth into the Commonwealth of Nations and made it possible for republics (such as the newly independent India) to remain its members.[14][15] In the South African context, republicanism was mainly identified with Afrikaner Conservatism and with tighter racial segregation.[16]

Death

On 29 May 1950, a week after the public celebration of his eightieth birthday in Johannesburg and Pretoria, Field Marshal Jan Smuts suffered a coronary thrombosis. He died of a subsequent heart attack on his family farm of Doornkloof, Irene, near Pretoria, on 11 September 1950.[6]

Relations with Churchill

In 1899, Smuts interrogated the young Winston Churchill, who had been captured by Afrikaners during the Boer War, which was the first time they met. The next time was in 1906, while Smuts was leading a mission about South Africa's future to London before Churchill, then Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies. The British Cabinet shared Churchill's sympathetic view, which led to self-government within the year, followed by dominion status for the Union of South Africa in 1910. Their association continued in the First World War, when Lloyd George appointed Smuts, in 1917, to the war cabinet in which Churchill served as Munitions Minister. By then, both had formed a fast friendship that continued through Churchill's "wilderness years" and the Second World War, to Smuts's death. Charles Wilson, 1st Baron Moran, Churchill's personal physician, wrote in his diary:

Smuts is the only man who has any influence with the PM; indeed, he is the only ally I have in pressing counsels of common sense on the PM. Smuts sees so clearly that Winston is irreplaceable, that he may make an effort to persuade him to be sensible.[17]

Churchill:

Smuts and I are like two old love-birds moulting together on a perch, but still able to peck.[17]

When Eden said at a meeting of the Chiefs of Staff (29 October 1942) that Montgomery's Middle East offensive was "petering out", after having some late night drinks with Churchill the previous night, Alan Brooke had told Churchill "fairly plainly" what he thought of Eden's ability to judge the tactical situation from a distance (Churchill was always impatient for his generals to attack at once). He was supported at the Chiefs of Staff meeting by Smuts.[18] Brooke said he was fortunate to be supported by:

a flow of words from the mouth of that wonderful statesman. It was as if oil had been poured on the troubled waters. The temperamental film-stars returned to their tasks – peace reigned in the dove cot!

Views

Race and segregation

Smuts and his parties supported existing policies of racial discrimination in South Africa, taking a more moderate and ambiguous stance than the rival National Party, and he later endorsed the relatively liberal proposals of the Fagan Commission.[19][20]

At the Imperial Conference of 1925 Smuts stated:

If there was to be equal manhood suffrage over the Union, the whites would be swamped by the blacks. A distinction could not be made between Indians and Africans. They would be impelled by the inevitable force of logic to go the whole hog, and the result would be that not only would the whites be swamped in Natal by the Indians but the whites would be swamped all over South Africa by the blacks and the whole position for which the whites had striven for two hundred years or more now would be given up. So far as South Africa was concerned, therefore, it was a question of impossibility. For white South Africa it was not a question of dignity but a question of existence.[21][22]

Smuts was, for most of his political life, a vocal supporter of segregation of the races, and in 1929 he justified the erection of separate institutions for black and white people in tones prescient of the later practice of apartheid:

The old practice mixed up black with white in the same institutions, and nothing else was possible after the native institutions and traditions had been carelessly or deliberately destroyed. But in the new plan there will be what is called in South Africa "segregation"; two separate institutions for the two elements of the population living in their own separate areas. Separate institutions involve territorial segregation of the white and black. If they live mixed together it is not practicable to sort them out under separate institutions of their own. Institutional segregation carries with it territorial segregation.[23]

In general, Smuts's view of black Africans was patronising: he saw them as immature human beings who needed the guidance of whites, an attitude that reflected the common perceptions of most westerners in his lifetime. Of black Africans he stated that:

These children of nature have not the inner toughness and persistence of the European, not those social and moral incentives to progress which have built up European civilization in a comparatively short period.[23]

Although Gandhi and Smuts were adversaries in many ways, they had a mutual respect and even admiration for each other. Before Gandhi returned to India in 1914, he presented General Smuts with a pair of sandals (now held by Ditsong National Museum of Cultural History) made by Gandhi himself. In 1939, Smuts, then prime minister, wrote an essay for a commemorative work compiled for Gandhi's 70th birthday and returned the sandals with the following message: "I have worn these sandals for many a summer, even though I may feel that I am not worthy to stand in the shoes of so great a man."[24]

Smuts is often accused of being a politician who extolled the virtues of humanitarianism and liberalism abroad while failing to practise what he preached at home in South Africa. This was most clearly illustrated when India, in 1946, made a formal complaint in the UN concerning the legalised racial discrimination against Indians in South Africa. Appearing personally before the United Nations General Assembly, Smuts defended the policies of his government by fervently pleading that India's complaint was a matter of domestic jurisdiction. However, the General Assembly censured South Africa for its racial policies[25] and called upon the Smuts government to bring its treatment of the South African Indians in conformity with the basic principles of the United Nations Charter.[25][26]

At the same conference, the African National Congress President General Alfred Bitini Xuma along with delegates of the South African Indian Congress brought up the issue of the brutality of Smuts's police regime against the African Mine Workers' Strike earlier that year as well as the wider struggle for equality in South Africa.[27]

In 1948, he went further away from his previous views on segregation when supporting the recommendations of the Fagan Commission that Africans should be recognised as permanent residents of White South Africa, and not merely as temporary workers who belonged in the reserves.[19] This was in direct opposition to the policies of the National Party that wished to extend segregation and formalise it into apartheid. There is, however, no evidence that Smuts ever supported the idea of equal political rights for black and white people. Despite this, he did say:

The idea that the Natives must all be removed and confined in their own kraals is in my opinion the greatest nonsense I have ever heard.[28]

The Fagan Commission did not advocate the establishment of a non-racial democracy in South Africa, but rather wanted to liberalise influx controls of black people into urban areas in order to facilitate the supply of black African labour to the South African industry. It also envisaged a relaxation of the pass laws that had restricted the movement of black South Africans in general.[29]

In the assessment of South African Cambridge professor Saul Dubow, "Smuts's views of freedom were always geared to securing the values of western Christian civilization. He was consistent, albeit more flexible than his political contemporaries, in his espousal of white supremacy."[30]

While in academia, Smuts pioneered the concept of holism, which he defined as "[the] fundamental factor operative towards the creation of wholes in the universe" in his 1926 book, Holism and Evolution.[31][32] Smuts's formulation of holism has been linked with his political-military activity, especially his aspiration to create a league of nations. As one biographer said:

It had very much in common with his philosophy of life as subsequently developed and embodied in his Holism and Evolution. Small units must develop into bigger wholes, and they in their turn again must grow into larger and ever-larger structures without cessation. Advancement lay along that path. Thus the unification of the four provinces in the Union of South Africa, the idea of the British Commonwealth of Nations, and, finally, the great whole resulting from the combination of the peoples of the earth in a great league of nations were but a logical progression consistent with his philosophical tenets.[33]

Zionism

In 1943 Chaim Weizmann wrote to Smuts, detailing a plan to develop Britain's African colonies to compete with the United States. During his service as Premier, Smuts personally fundraised for multiple Zionist organisations.[34] His government granted de facto recognition to Israel on 24 May 1948.[35] However, Smuts was deputy prime minister when the Hertzog government in 1937 passed the Aliens Act that was aimed at preventing Jewish immigration to South Africa. The act was seen as a response to growing anti-Semitic sentiments among Afrikaners.[36]

Smuts lobbied against the White Paper of 1939,[37] and several streets and a kibbutz, Ramat Yohanan, in Israel are named after him.[35] He also wrote an epitaph for Weizmann, describing him as "the greatest Jew since Moses."[38] Smuts once said:

Great as are the changes wrought by this war, the great world war of justice and freedom, I doubt whether any of these changes surpass in interest the liberation of Palestine and its recognition as the Home of Israel.[39]

Legacy

One of his greatest international accomplishments was aiding in the establishment of the League of Nations, the exact design and implementation of which relied upon Smuts.[40] He later urged the formation of a new international organisation for peace – the United Nations. Smuts wrote the first draft of the preamble to the United Nations Charter, and was the only person to sign the charters of both the League of Nations and the UN. He played a key role in the development of trusteeship and the League of Nations mandate system.[41] He sought to redefine the relationship between the United Kingdom and her colonies, helping to establish the British Commonwealth, as it was known at the time. This proved to be a two-way street; in 1946 the General Assembly requested the Smuts government to take measures to bring the treatment of Indians in South Africa into line with the provisions of the United Nations Charter.[25]

In 1932, the kibbutz Ramat Yohanan in Israel was named after him. Smuts was a vocal proponent of the creation of a Jewish state, and spoke out against the rising antisemitism of the 1930s.[42] A street in the German Colony neighbourhood of Jerusalem and a boulevard in Tel Aviv are named in his honour.[43]

In 1917, part of the M27 route in Johannesburg was renamed from Pretoria Road[44] to Jan Smuts Avenue.[45]

The international airport serving Johannesburg was known as Jan Smuts Airport from its construction in 1952 until 1994. In 1994, it was renamed to Johannesburg International Airport to remove any political connotations. In 2006, it was renamed again to its current name, OR Tambo International Airport, after the ANC politician Oliver Tambo.[46]

In 2004, Smuts was named by voters in a poll held by the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) as one of the top ten Greatest South Africans of all time. The final positions of the top ten were to be decided by a second round of voting but the programme was taken off the air owing to political controversy and Nelson Mandela was given the number one spot based on the first round of voting. In the first round, Field Marshal Smuts came ninth.[47]

Mount Smuts, a peak in the Canadian Rockies, is named after him.[48]

In August 2019, the South African Army Regiment Westelike Provinsie was renamed after Smuts as the General Jan Smuts Regiment.[49][50]

The Smuts House Museum at Smuts's home in Irene is dedicated to promoting his legacy.[51]

Orders, decorations and medals

Field Marshal Smuts was honoured with orders, decorations and medals from several countries.[52]

|

South Africa

United Kingdom

|

Belgium

Denmark Egypt

France

Greece

Netherlands

Portugal

United States

|

References

- ^ Root, Waverley (1952). "Jan Christian Smuts. 1870–1950". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 8 (21): 271–73. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1952.0017. JSTOR 768812. S2CID 202575333.

- ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةNicholas, 2014 - ^ "J.B.M. Hertzog: prime minister of South Africa". Britannica. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ "No. 35172". The London Gazette (Supplement). 23 May 1941. p. 3004.

- ^ Colville, pp. 269–271

- ^ أ ب ت Heathcote, p. 266

- ^ Mazower, Mark (2013). No Enchanted Palace: The End of Empire and the Ideological Origins of the United Nations (in الإنجليزية). Princeton University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-691-15795-5.

- ^ Mazower, Mark (2013). No Enchanted Palace: The End of Empire and the Ideological Origins of the United Nations (in الإنجليزية). Princeton University Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-691-15795-5.

- ^ "Record from The Nomination Database for the Nobel Prize in Peace, 1901–1956". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ^ "Social assistance in South Africa: Its potential impact on poverty" (PDF). Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ "Seating plan for the Ball Supper Room". Royal Collection. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ^ Chancellors of the University of Cambridge. British History Online. Retrieved on 30 July 2012.

- ^ Union Defence Force Order No.4114. 5 July 1949

- ^ Colville, Sir John (2004). The Fringes of Power. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 1-84212-626-1.

- ^ "1949–1999: Fifty Years of a Renewing Commonwealth". The Round Table. 88 (350): 1–27. April 1999. doi:10.1080/003585399108072.

- ^ Muller (1975), p. 508.

- ^ أ ب Coutenay, Paul H., Great Contemporaries: Jan Christian Smuts, The Churchill Project, Hillsdale College, 1 December 2007

- ^ Alanbrooke 2001, pp. 335,336.

- ^ أ ب "Jan Christiaan Smuts, South African History Online". Sahistory.org.za. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ Meredith, Martin. In the name of apartheid: South Africa in the postwar period. 1st U.S. ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1988

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةForeignAffairsDuBois - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةTheNewNegroDuBois - ^ أ ب "Race Segregation In South Africa New Policies and Factors in Race Problems" (PDF). Journal of Heredity. Oxford Journals. 1930. p. 21 (5): 225–233. ISSN 0022-1503. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Following the footsteps of a great man". Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2006.

- ^ أ ب ت "United Nations General Assembly Resolution A/RES/44(I)" (PDF). United Nations General Assembly. 8 December 1946. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ^ "Unverified article attributed to the Delhi News Chronicle". South African Communist Party. 25 September 1949. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ R.E.Press. "The miners strike of 1946". Anc.org.za. Archived from the original on 8 April 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "General Jan Christiaan Smuts". South African History Online. 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ "Fagan Commission and Report". Africanhistory.about.com. 26 May 1948. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ Dubow, Saul H. (January 2008). "Smuts, the United Nations and the Rhetoric of Race and Rights". Journal of Contemporary History. 43 (1): 45–74. doi:10.1177/0022009407084557. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 30036489. S2CID 154627008.

- ^ Smuts, J.C. (1927). Holism and evolution. Рипол Классик. ISBN 978-5-87111-227-4.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:0 - ^ Crafford, p. 140

- ^ Hunter, pp 21–22

- ^ أ ب Beit-Hallahmi, pp 109–111

- ^ "South Africa – The Great Depression and the 1930s". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ Crossman, p. 76

- ^ Lockyer, Norman. Nature, digitized 5 February 2007. Nature Publishing Group.

- ^ Klieman, p. 16

- ^ Crafford, p. 141

- ^ Haas, Ernst B. (1952). "The Reconciliation of Conflicting Colonial Policy Aims: Acceptance of the League of Nations Mandate System". International Organization (in الإنجليزية). 6 (4): 521–536. doi:10.1017/S0020818300017082. ISSN 1531-5088.

- ^ "Jewish American Year Book 5695" (PDF). Jewish Publication Society of America. 1934. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 12 August 2006.

- ^ "Jan Smuts given honor where honor was due". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 25 July 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ "JAN SMUTS AVENUE". Blue Plaques of South Africa. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ "Louis Botha Avenue Development Corridor" (PDF). City of Johannesburg. SAJR. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ "The History of OR Tambo International Airport". Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ^ "SA se gewildste is Nelson Mandela". Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ^ Place-names of Alberta. Ottawa. 1928. hdl:2027/mdp.39015070267029.

- ^ "New Reserve Force unit names". defenceWeb (in الإنجليزية). 7 August 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Renaming process has resulted in an Army structure that truly represents SA". www.iol.co.za (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Smuts House". www.smutshouse.co.za. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Alexander, E. G. M., Barron G. K. B. and Bateman, A. J. (1985). South African Orders, Decorations and Medals (photograph page 109)

Sources

Primary

- Hancock, W. K.; van der Poel, J. (1966–1973). Selections from the Smuts Papers, 1886–1950. Vol. 7.

- Smuts, J. C. (1934). Freedom. Alexander Maclehose & Co. ASIN B006RIGNWS.

- Smuts, J. C. (1940). The Folly of Neutrality – Speech by the Prime Minister. Johannesburg: Union Unity Truth Service. OCLC 10513071.

Secondary

- Alanbrooke, Field Marshal Lord (2001). War Diaries 1939–1945. Phoenix Press. ISBN 1-84212-526-5.

- Beit-Hallahmi, Benjamin (1988). The Israeli Connection: Whom Israel Arms and Why. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1850430698.

- Cameron, Trewhella (1994). Jan Smuts: An Illustrated Biography. Human & Rousseau. ISBN 978-0-798-13343-2.

- Colville, John (2004). The Fringes of Power. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84758-8.

- Crafford, F. S. (1943). Jan Smuts: A Biography. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4179-9290-5.

- Crawford, Neta (2002). Argument and Change in World Politics: Ethics, Decolonization and Humanitarian Intervention. Cambridge University. ISBN 0-521-00279-6.

- Crossman, R. H. S. (1960). A nation reborn;: A personal report on the roles played by Weizmann, Bevin and Ben-Gurion in the story of Israel. Atheneum Publishers. ASIN B0007DU0X2.

- Crowe, J. H. V. (2009). General Smuts' Campaign in East Africa. Naval and Military Press. ISBN 978-1-843-42949-4.

- Dugard, John (1973). The South West Africa/Namibia Dispute: Documents and Scholarly Writings on the Controversy Between South Africa and The United Nations. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02614-4.

- First, Ruth (1963). South West Africa. Penguin. ASIN B004F1QT50.

- Gooch, John (2000). The Boer War: Direction, Experience and Image. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-714-65101-9.

- Hancock, W. K. (1962). Smuts: 1. The Sanguine Years, 1870—1919. Cambridge University. ASIN B0006AY7U8.

- Hancock, W. K. (1968). Smuts: 2. Fields of Force, 1919–1950. Cambridge University. ISBN 978-0-521-05188-0.

- Heathcote, Tony (1999). The British Field Marshals 1736–1997. Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-696-5.

- Howe, Quincy (1949). A World History of Our Own Times. Simon and Schuster. ASIN B0011VZAL6.

- Hunter, Jane (1987). Israeli Foreign Policy: South Africa and Central America. Spokesman Books. ISBN 978-0-851-24485-3.

- Kee, Robert (1988). Munich. Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-12537-3.

- Klieman, Aaron S. (1991). Recognition of Israel: An End & a New Beginning: An End and a New Beginning. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-824-07361-9.

- Smuts, J. C. (1952). Jan Christian Smuts by his son. Cassell. ISBN 978-1-920-09129-3.

- Spies, S.B.; Natrass, G. (1994). Jan Smuts: Memoirs of the Boer War. Jonathan Ball, Johannesburg. ISBN 978-1-868-42017-9.

- Woodward, David R. (1998). Field Marshal Sir William Robertson. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-95422-6.

Further reading

- Armstrong, H. C. (1939). Grey Steel: A Study of Arrogance. Penguin. ASIN B00087SNP4.

- Friedman, Bernard (1975). Smuts: A Reappraisal. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-049-20045-6.

- Geyser, Ockert (2002). Jan Smuts and His International Contemporaries. Covos Day Books. ISBN 978-1-919-87410-4.

- Hutchinson, John (1946). A Botanist in Southern Africa. PR Gawthorn Ltd. ASIN B0010PNVVO.

- Ingham, Kenneth (1986). Jan Christian Smuts: The Conscience of a South African. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-43997-2.

- Joubert, Anton (2023). Jan Smuts, 1870–1950: A Photobiography. Pretoria: Protea. ISBN 9781485313847. OCLC 1372393402.

- Katz, David Brock (2022). General Jan Smuts and His First World War in Africa, 1914–1917. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-63624-017-6.

- Lentin, Antony (2010). General Smuts: South Africa. Haus. ISBN 978-1-905791-82-8.

- Millin, Sarah (1936). General Smuts. Vol. 2. Faber & Faber. ASIN B0006AN8PS.

وصلات خارجية

- أعمال من يان سموتس في مشروع گوتنبرگ

- Works by or about يان سموتس at Internet Archive

- "Revisiting Urban African Policy and the Reforms of the Smuts Government, 1939–48", by Gary Baines

- Africa and Some World Problems by Jan Smuts at the Internet Archive

- Holism and Evolution by Jan Smuts at the Internet Archive

- The White man's task by Jan Smuts

- Newspaper clippings about يان سموتس in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

قالب:JanSmutsFooter قالب:SAPremiers

قالب:SouthAfricaJusticeMinisters قالب:SouthAfricaDefenceMinisters

- Pages containing London Gazette template with parameter supp set to y

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Pages using infobox officeholder with unknown parameters

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages using authority control with unknown parameters

- مواليد 1870

- وفيات 1950

- South African mountain climbers

- People from the West Coast District Municipality

- أفريكانر

- South African people of Dutch descent

- South African Party (Union of South Africa) politicians

- United Party (South Africa) politicians

- رؤساء وزراء جنوب أفريقيا

- Defence ministers of South Africa

- Finance ministers of South Africa

- Members of the House of Assembly of South Africa

- يان سموتس

- فلاسفة القرن 20

- خريجو جامعة كمبردج

- Apartheid in South Africa

- جنرالات جنوب أفريقيا

- مشيرون بريطانيون

- مستشارو جامعة كمبردج

- زملاء الجمعية الملكية

- Legion of Frontiersmen members

- أعضاء مرتبة الاستحقاق

- أعضاء مرتبة رفاق الشرف

- أعضاء مجلس الخاصة الملكية بالمملكة المتحدة

- Grand Cordons of the Order of Leopold (Belgium)

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the African Star

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre (Belgium)

- قادة جوقة الشرف

- Recipients of King Christian X's Liberty Medal

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Tower and Sword

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Redeemer

- قيمو جامعة سانت أندروز

- South African military personnel

- جنوب افارقة في الحرب العالمية الأولى

- جنوب افارقة في الحرب العالمية الثانية

- علماء أنظمة

- زعماء سياسيون في الحرب العالمية الثانية

- صهاينة

- أفراد عسكريون من الجمهورية الجنوب أفريقية في حرب البوير الثانية

- Ministers of Home Affairs of South Africa

- جنوب أفريقيون