معهد كوك لأبحاث السرطان المتكاملة

| تأسس | October 9, 2007 |

|---|---|

| نوع البحث | Basic (non-clinical) research |

| الميزانية | $93.2 million[1] |

مجال البحث | Cancer research |

| المدير | Matthew Vander Heiden |

| الكلـِّية | 29[2] |

| الموظفون | 500[2] |

| العنوان | 77 Massachusetts Ave. Building 76 |

| الموقع | Cambridge, Massachusetts |

| الحرم | 180،000 أقدام مربعة (17،000 m2) |

| الاقترانات | National Cancer Institute |

الوكالة المشغـِّلة | Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | ki.mit.edu |

The Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT (/koʊk/ KOHK; also referred to as the Koch Institute or KI) is a cancer research center affiliated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. The institute is one of seven National Cancer Institute-designated basic laboratory cancer centers in the United States.[3]

The institute was launched in October 2007 with a $100 million grant from David H. Koch and the 180،000 أقدام مربعة (17،000 m2) research facility opened in December 2010, replacing the MIT Center for Cancer Research (CCR).[4][5] The institute is affiliated with 29 MIT faculty members in both the Schools of Engineering and Science.[6]

التاريخ

In 1974, the Center for Cancer Research was founded by 1969 Nobel laureate Salvador Luria to study basic biological processes related to cancer. The center researches the genetic and molecular basis of cancer, how alterations in cellular processes affect cell growth and behavior, and how the immune system develops and recognizes antigens.[7] The CCR was both a physical research center as well as an organizing body for the larger MIT cancer research community of over 500 researchers.[8] Financial support for the CCR primarily came from Center Core grant from the National Cancer Institute as well as research project grants from the National Institutes of Health, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and foundation support. The CCR research groups were successful in identifying oncogenes, immunology of T lymphocytes, and roles of various cellular proteins. The CCR produced four Nobel Laureates: David Baltimore (1975), Susumu Tonegawa (1987), Phillip Sharp (1993), and H. Robert Horvitz (2002).[9]

In 2006, President Susan Hockfield announced plans for a new CCR center to support and expand cancer research performed by biologists and engineers.[8][9] A $20 million grant was made by the Ludwig Fund, part of Ludwig Cancer Research, in November 2007 to support a Center for Molecular Oncology to be administered by the CCR.[10] In 2007, MIT announced it had received a $100 million gift from David H. Koch, the executive vice president of the oil conglomerate Koch Industries. Koch graduated from MIT with bachelor's and master's degrees in chemical engineering and served on the university's board of directors since 1988. Koch survived a prostate cancer diagnosis in 1992, previously donated $25 million over ten years to MIT to support cancer research, and is the namesake of the university's Koch Biology Building.[11] The gift supported the construction of the estimated $240–$280 million facility, on the condition that MIT build the center even if fund raising fell short.[5]

Mission

The Koch Institute emphasizes basic research into how cancer is caused, progresses, and responds to treatment. Unlike many other NCI Cancer Centers, it will not provide medical care or conduct clinical research, but it partners with oncology centers such as the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital's Cancer Center.[12] The institute combines the existing faculty of the CCR with an equivalent number of engineering faculty to promote interdisciplinary approaches to diagnosing, monitoring, and treating cancer.[1]

The Koch Institute has identified five areas of research that it believes are critical for controlling cancer: Developing nanotechnology-based cancer therapeutics, creating novel devices for cancer detection and monitoring, exploring the molecular and cellular basis of metastasis, advancing personalized medicine through analysis of cancer pathways and drug resistance, engineering the immune system to fight cancer.[13]

المرافقون

The Koch Institute is home to faculty members from various departments, including Biology, Chemistry, Mechanical Engineering, and Biological Engineering; more than 40 laboratories and 500 researchers across the campus.[1] Koch Institute faculty teach classes at MIT, as well as train graduate and undergraduate students as well as postdoctoral fellows. The Koch Institute is affiliated with two current Nobel Laureates (Horvitz and Sharp), eighteen members of the National Academy of Sciences, eight members of the National Academy of Engineering, five National Medal of Science laureates, and ten Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigators, and one MacArthur Foundation Fellowship recipient.[14]

Notable faculty members affiliated with the Koch Institute include:[2]

Building

The 180،000 أقدام مربعة (17،000 m2) research facility is located on the corner of Main Street and Ames Street near Kendall Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The building is located opposite the Whitehead Institute and Broad Institute and near the biology and chemical engineering buildings on the north-eastern end of MIT's campus. MIT broke ground on Building 76 in March 2008,[6] a topping-off ceremony was held in February 2009,[15] and the building was dedicated on March 4, 2011.[16]

The building was designed by Cambridge-based architecture firm Ellenzweig, which designed several other buildings on the MIT campus.[17] The structural engineer was LeMessurier. Designed to encourage interaction and collaboration, the building employs both dedicated lab space as well as common areas, and features a ground-floor gallery exhibiting art and technical displays related to biomedical research.[1] The building includes facilities for bioinformatics and computing, genomics, proteomics and flow cytometry, large-scale cell and animal facilities for genetic engineering and testing, advanced imaging equipment, and nanomaterials characterization labs.[6]

النشاط منذ 2007

لا يزال معهد كوك ممولاً بمنحة من مركز المعهد الوطني للسرطان، بالإضافة إلى 110 مشروع ممول بالكامل. في الفترة 2017-2018 بلغ إجمالي حجم الأبحاث 93.2 مليون دولار أمريكي.[1] اعتباراً من عام 2009، تشمل المنح البارزة اتحاد نماذج الفئران للسرطان، وبرنامج علم الأحياء التكاملي للسرطان، ومراكز التميز في تكنولوجيا النانو والسرطان.[12]

عام 2011، حدد العلماء في المعهد تغيراً وراثياً يجعل سرطان الرئة أكثر عرضة للانتشار في جميع أنحاء الجسم وقد يساعد العلماء على تطوير أدوية جديدة لمحاربة الأورام الثانوية.[18]

عام 2020، قام أليس شالك، وكريستوفر لڤ، وتراڤيس هيوز، ومارك وادزورث بتطوير بروتوكول محدث لطريقة تسلسل الحمض النووي الريبي منخفضة المدخلات المستخدمة بشكل شائع Seq-Well، مما أدى إلى زيادة دقة الإخراج بمقدار عشرة أضعاف.[19]

العضلات الاصطناعية

ترجع الحركة إلى التنسيق بين ألياف العضلات الهيكلية العديدة، حيث ترتجف وتنقبض جميعها بتناغم. وبينما تصطف بعض العضلات في اتجاه واحد، تُشكل عضلات أخرى أنماطاً معقدة، مما يساعد أجزاء الجسم على الحركة بطرق متعددة. في السنوات الأخيرة، نظر العلماء والمهندسون إلى العضلات كمحركات محتملة للروبوتات "المهجنة حيوياً"، وهي آلات تعمل بألياف عضلية لينة مزروعة اصطناعياً. تستطيع هذه الروبوتات الحيوية الالتواء والتحرك في مساحات لا تستطيع الآلات التقليدية القيام بها. ومع ذلك، لم يتمكن الباحثون في معظم الأحيان إلا من تصنيع عضلات اصطناعية تسحب في اتجاه واحد، مما يحد من نطاق حركة أي روبوت.[20]

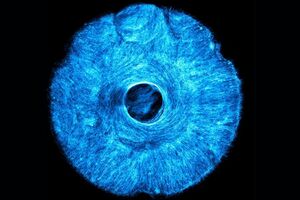

في مارس 2025 طوّر مهندسو معهد مساتشوستس للتكنولوجيا طريقةً لتنمية أنسجة عضلية اصطناعية تتحرك وتنثني في اتجاهات مُنسّقة متعددة. ولإثبات ذلك، قاموا بتنمية بنية اصطناعية تعمل بالطاقة العضلية، وتتحرك مركزياً وشعاعياً، تماماً كما تعمل قزحية العين البشرية على توسيع وتضييق الحدقة. صنع الباحثون القزحية الاصطناعية باستخدام أسلوب "الختم" الجديد الذي طوروه. أولاً، طبعوا ختماً يدوياً بتقنية الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد، مزخرفاً بأخاديد مجهرية، كل منها بحجم خلية واحدة. ثم ضغطوا الختم على هلام مائي ناعم، وزرعوا في الأخاديد الناتجة خلايا عضلية حقيقية. نمت الخلايا على طول هذه الأخاديد داخل الهلام المائي، مُشكلةً أليافياً. عندما حفّز الباحثون الألياف، انقبضت العضلة في اتجاهات متعددة، مُتبعةً اتجاه الألياف.

تقول ريتو رامان، أستاذة هندسة الأنسجة في قسم الهندسة الميكانيكية بمعهد مساتشوستس للتكنولوجيا: "من خلال تصميم القزحية، نعتقد أننا أثبتنا أول روبوت يعمل بالعضلات الهيكلية ويُولّد قوة في أكثر من اتجاه. وقد مكّننا هذا النهج الفريد من ذلك". يقول الفريق أنه يمكن طباعة الختم باستخدام طابعات ثلاثية الأبعاد، وتزويده بأنماط مختلفة من الأخاديد المجهرية. ويمكن استخدام الختم لتنمية أنماط معقدة من العضلات، وربما أنواع أخرى من الأنسجة الحيوية، مثل الخلايا العصبية وخلايا القلب، والتي تشبه نظيراتها الطبيعية في الشكل والسلوك. وتقول رامان: "نريد أن نصنع أنسجةً تُحاكي التعقيد المعماري للأنسجة الحقيقية. ولتحقيق ذلك، نحتاج حقاً إلى هذا القدر من الدقة في التصنيع".

نشرت رامان وزملاؤها نتائجهم مفتوحة المصدر في 17 مارس 2025 في مجلة علوم المواد الحيوية. ومن بين المؤلفين المشاركين في معهد مساتشوستس للتكنولوجيا: تامارا روسي، ولورا شويندمان، وسونيكا كوهلي، وماهيرا باوا، وپاڤانكومار أوماشانكار، إلى جانب روي هابا، وأورين تشايتشيان، وأيليت ليسمان من جامعة تل أبيب. يهدف الفريق إلى هندسة مواد حيوية تحاكي استشعار ونشاط واستجابة الأنسجة الحقيقية في الجسم. ويسعى فريقها البحثي، على نطاق أوسع، إلى تطبيق هذه المواد المُهندَسة حيوياً في مجالات متنوعة، بدءاً من الطب ووصولاً إلى الآلات. على سبيل المثال، تسعى رامان إلى تصنيع أنسجة اصطناعية تُعيد وظائف الأشخاص الذين يعانون من إصابات عصبية عضلية. كما تستكشف استخدام العضلات الاصطناعية في الروبوتات اللينة، مثل السباحين الذين يعتمدون على العضلات، والذين يتحركون في الماء بمرونة تُشبه مرونة الأسماك.

سبق لرامان أن طورت ما يمكن اعتباره منصات رياضية وبرامج تدريبية لخلايا عضلية مزروعة في المعمل. صممت هي وزملاؤها "سجادة" من الهلام المائي تُشجّع خلايا العضلات على النمو والاندماج في ألياف دون أن تتقشر. كما ابتكرت طريقةً لـ"تدريب" الخلايا عن طريق هندستها وراثياً لتنقبض استجابة لنبضات الضوء. كما ابتكرت مجموعتها طرقًا لتوجيه خلايا العضلات للنمو في خطوط طويلة ومتوازية، تُشبه العضلات المخططة الطبيعية. ومع ذلك، شكّل تصميم أنسجة عضلية اصطناعية تتحرك في اتجاهات متعددة ومتوقعة تحديًا لمجموعتها ومجموعات أخرى. من الميزات الرائعة للأنسجة العضلية الطبيعية أنها لا تتجه في اتجاه واحد. على سبيل المثال، العضلات الدائرية في قزحية العين وحول القصبة الهوائية. وحتى في الذراعين والساقين، لا تتجه الخلايا العضلية بشكل مستقيم، بل بزاوية، كما يشير رامان. "للعضلات الطبيعية اتجاهات متعددة في الأنسجة، لكننا لم نتمكن من محاكاة ذلك في عضلاتنا المُهندسة."

أثناء تفكيرهم في طرق تنمية أنسجة عضلية متعددة الاتجاهات، توصل الفريق إلى فكرة بسيطة ومدهشة: الختم. مستوحين جزئياً من قالب الجيلي الكلاسيكي، سعى الفريق إلى تصميم ختم بأنماط مجهرية يمكن طبعها على هيدروجيل، على غرار حصائر تدريب العضلات التي طورتها المجموعة سابقاً. يمكن بعد ذلك أن تكون أنماط الحصيرة المطبوعة بمثابة خارطة طريق تتبعها خلايا العضلات وتنمو. الفكرة بسيطة، لكن كيف تصنع ختماً بخصائص صغيرة جداً، وكيف تختم شيئاً فائق النعومة. هذا الجل أنعم بكثير من الجيلي، وهو مادة يصعب صبها، لأنه يتمزق بسهولة، كما يقول رامان. جرب الفريق تنويعات على تصميم الختم، وتوصلوا في النهاية إلى نهجٍ أثبت نجاحه بشكلٍ مدهش. صنع الباحثون ختماً صغيراً محمولاً باليد باستخدام معدات طباعة عالية الدقة في برنامج MIT.nano، مما مكنهم من طباعة أنماط معقدة من الأخاديد، يبلغ عرض كل منها تقريباً عرض خلية عضلية واحدة، على قاعدة الختم. قبل ضغط الختم على حصيرة هيدروجيل، غطوا القاعدة ببروتينٍ ساعد الختم على النقش بالتساوي على الجل وتقشيره دون التصاق أو تمزق.

كإثبات عملي، طبع الباحثون ختماً بنمط يشبه العضلات المجهرية في قزحية العين البشرية. تتكون القزحية من حلقةٍ عضليةٍ تُحيط بالحدقة. تتكون هذه الحلقة العضلية من دائرةٍ داخليةٍ من أليافٍ عضليةٍ مُرتبةٍ مركزياً، مُتبعةً نمطاً دائرياً، ودائرةٍ خارجيةٍ من أليافٍ تمتد شعاعياً، كأشعة الشمس. يعمل هذا البناء المُعقد معاً على تضييق أو توسيع الحدقة. بمجرد أن ضغطت رامان وزملاؤها نمط القزحية على حصيرة هيدروجيل، غطوا الحصيرة بخلايا معدلة وراثياً للاستجابة للضوء. في غضون يوم واحد، سقطت الخلايا في الأخاديد المجهرية وبدأت بالاندماج مع الألياف، متتبعةً أنماط القزحية، لتنمو في النهاية لتُشكّل عضلة كاملة، ببنية وحجم مماثلين للقزحية الحقيقية. عندما حفّز الفريق القزحية الاصطناعية بنبضات ضوئية، انقبضت العضلة في اتجاهات متعددة، على غرار قزحية العين البشرية. وتشير رامان إلى أن القزحية الاصطناعية التي صممها الفريق مصنوعة من خلايا العضلات الهيكلية، المسؤولة عن الحركة الإرادية، بينما تتكون الأنسجة العضلية في قزحية العين البشرية الحقيقية من خلايا العضلات الملساء، وهي نوع من الأنسجة العضلية اللاإرادية. وقد اختاروا تصميم خلايا العضلات الهيكلية بنمط يشبه القزحية لإظهار القدرة على تصنيع أنسجة عضلية معقدة ومتعددة الاتجاهات.

في هذا العمل، أردنا أن نبرهن على إمكانية استخدام أسلوب الختم هذا لصنع روبوت قادر على القيام بأشياء لم تستطع الروبوتات السابقة التي تعمل بالطاقة العضلية القيام بها، كما تقول رامان. "اخترنا العمل على خلايا العضلات الهيكلية. ولكن لا شيء يمنعنا من القيام بذلك مع أي نوع آخر من الخلايا." وتشير إلى أنه على الرغم من استخدام الفريق لتقنيات الطباعة الدقيقة، إلا أنه يمكن أيضاً تصميم الختم باستخدام طابعات ثلاثية الأبعاد تقليدية. وتخطط هي وزملاؤها مستقبلاً لتطبيق طريقة الختم على أنواع أخرى من الخلايا، بالإضافة إلى استكشاف هياكل عضلية مختلفة وطرق تنشيط عضلات اصطناعية متعددة الاتجاهات للقيام بعمل مفيد. وتقول رامان: "بدلاً من استخدام المحركات الصلبة الشائعة في الروبوتات تحت الماء، إذا استطعنا استخدام روبوتات حيوية مرنة، يمكننا التنقل بكفاءة أكبر في استهلاك الطاقة، مع كونها قابلة للتحلل الحيوي بالكامل ومستدامة". هذا العمل مدعوم جزئاً من قبل مكتب أبحاث البحرية الأمريكي، ومكتب أبحاث الجيش الأمريكي، والمؤسسة الوطنية للعلوم، والمعاهد الوطنية للصحة في الولايات المتحدة.

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Annual Reports to the President, 2017–2018: Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research". Office of the President, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- ^ أ ب ت "People". The Koch Institute, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ "David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 2023-06-03.

- ^ Trafton, Anne (October 9, 2007). "David H. Koch gives $100 million to MIT for cancer research". MIT News Office.

- ^ أ ب Strout, Erin (October 10, 2007). "MIT Receives $100-Million Gift for Cancer-Research Center". The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- ^ أ ب ت Trafton, Anne (March 8, 2008). "MIT breaks ground for Koch institute". MIT News Office.

- ^ "Annual Reports to the President, 1994–1995: Center for Cancer Research". Office of the President, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ أ ب "Annual Reports to the President, 2006–2007: Center for Cancer Research" (PDF). Office of the President, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ أ ب Thomson, Elizabeth (June 26, 2006). "Cancer Center highlights past, present research". MIT News Office.

- ^ Richards, Patti (November 14, 2006). "MIT receives major grant from the Ludwig Fund to tackle metastasis". MIT News Office.

- ^ "Lecture marks Koch Building naming cancer-research gift". MIT News Office. September 29, 1999.

- ^ أ ب "The Koch Institute - Frequently Asked Questions". The Koch Institute, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

- ^ "Research". The David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "The Koch Institute: Intramural Faculty". ki.mit.edu. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ^ "Highlights of Koch Institute Topping-Off Ceremony (video)". MIT News Office. February 20, 2009.

- ^ "While you were out". MIT News Office. September 2, 2009. Archived from the original on September 6, 2009.

- ^ Brobbey, Valery (February 26, 2008). "Cancer Building Groundbreaking Scheduled". The Tech.

- ^ Briggs, Helen (April 7, 2011). "Gene clue to how cancer spreads". BBC. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ "Technique to recover lost single-cell RNA-sequencing information: Boosting the efficiency of single-cell RNA-sequencing helps reveal subtle differences between healthy and dysfunctional cells". ScienceDaily (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ "Artificial muscle flexes in multiple directions, offering a path to soft, wiggly robots". معهد مساتشوستس للتكنولوجيا. 2025-03-17. Retrieved 2025-03-30.

External links

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Cancer research organizations

- Cancer organizations based in the United States

- NCI-designated cancer centers

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology research institutes

- Medical and health organizations based in Massachusetts

- Koch family

- 2007 establishments in Massachusetts