زيت زيتون

| Olive oil | |

Olive oil bottle. | |

تركيب الدهن

| |

|---|---|

| دهون مشبعة | Palmitic acid: 7.5–20.0 % Stearic acid: 0.5–5.0 % Arachidic acid: <0.8% Behenic acid: <0.3% Myristic acid: <0.1% Lignoceric acid: <1.0% |

| دهون غير مشبعة | yes |

| دهون أحادية عدم التشبع | Oleic acid: 55.0–83.0% Palmitoleic acid: 0.3–3.5% |

| دهون عديدة عدم التشبع | Linoleic acid: 3.5–21.0 % Linolenic acid: <1.5% |

الخواص

| |

| الطاقة الغذائية لكل 100g | 3700 kJ (890 kcal) |

| نقطة الانصهار | −6.0 °C (21 °F) |

| نقطة الغليان | 300 °C (570 °F) |

| Smoke point | 190 °C (375 °F) (virgin) 210 °C (410 °F) (refined) |

| Specific gravity at 20 °C | 0.9150–0.9180 (@ 15.5 °C) |

| اللزوجة عند 20 °م | 84 cP |

| Refractive index | 1.4677–1.4705 (virgin and refined) 1.4680–1.4707 (pomace) |

| قيمة اليود | 75–94 (virgin and refined) 75–92 (pomace) |

| قيمة الحمض | maximum: 6.6 (refined and pomace) 0.6 (extra-virgin) |

| قيمة التصبن | 184–196 (virgin and refined) 182–193 (pomace) |

| Peroxide value | 20 (virgin) 10 (refined and pomace) |

زيت الزيتون زيت نباتي يُستخرج بعصر حبات الزيتون الكاملة (ثمرة الزيتون الأوروبي، وهو محصول شجري تقليدي في حوض البحر المتوسط) واستخراج الزيت منها.

يُستخدم عادةً في الطهي لقلي الأطعمة، أو كتوابل، أو تتبيلة للسلطات. كما يُستخدم في بعض مستحضرات التجميل، والأدوية، والصابون، ووقود مصابيح الزيت التقليدية. وله استخدامات إضافية في بعض الديانات. يُعدّ الزيتون أحد النباتات الغذائية الرئيسية الثلاثة في مطبخ البحر المتوسط، إلى جانب القمح والعنب. وقد زُرعت أشجار الزيتون في منطقة البحر المتوسط منذ الألفية الثامنة قبل الميلاد.

في عام 2022، كانت إسبانيا أكبر مُنتج عالميًا، حيث صُنعت 24% من إجمالي الإنتاج العالمي. ومن بين كبار المُنتجين الآخرين إيطاليا واليونان وتركيا، حيث استحوذت مجتمعةً على 59% من السوق العالمية.[1]

يختلف تركيب زيت الزيتون باختلاف الصنف، والارتفاع، ووقت الحصاد، وعملية الاستخلاص. يتكون بشكل رئيسي من حمض الزيتيك (حتى 83%)، مع كميات أقل من الأحماض الدهنية الأخرى، بما في ذلك حمض زيت الكتان (حتى 21%) وحمض البالمتيك (حتى 20%). يُشترط ألا تزيد نسبة الحموضة الحرة في زيت الزيتون البكر الممتاز (EVOO) عن 0.8%، ويُعتبر ذو نكهة مميزة.

التاريخ

لطالما كان زيت الزيتون مكونًا شائعًا في مطابخ البحر الأبيض المتوسط، بما في ذلك المطبخ اليوناني والروماني القديم. جمع سكان العصر الحجري الحديث الزيتون البري، الذي نشأ في آسيا الصغرى، منذ الألفية الثامنة قبل الميلاد.[2][3]

إلى جانب استخدامه كغذاء، استُخدم زيت الزيتون في الطقوس الدينية، والطب، وكعامل إضاءة في مصابيح الزيت، وصناعة الصابون، ومنتجات العناية بالبشرة.[4][5]

استخدم الإسبرطيون وغيرهم من اليونانيين الزيت لتدليك أنفسهم أثناء ممارسة الرياضة في صالات الألعاب الرياضية. ومنذ بداياته في أوائل القرن السابع قبل الميلاد، انتشر استخدامه التجميلي بسرعة في جميع دول المدن اليونانية، إلى جانب تدريب الرياضيين عراة، واستمر قرابة ألف عام على الرغم من تكلفته الباهظة.

كما كان زيت الزيتون شائعًا كوسيلة لمنع الحمل؛ إذ أوصى أرسطو في كتابه "تاريخ الحيوانات" بوضع خليط من زيت الزيتون مع زيت الأرز، أو مرهم الرصاص، أو اللبان المر على عنق الرحم لمنع الحمل.[6]

الزراعة المبكرة

التاريخ الدقيق وموقع تدجين شجرة الزيتون غير واضحين. ربما نشأت شجرة الزيتون الحديثة في بلاد فارس وبلاد ما بين النهرين القديمة، ثم انتشرت إلى بلاد الشام، ثم إلى شمال أفريقيا لاحقًا، مع أن بعض العلماء يرجحون أن أصلها مصري.[7]

وصلت شجرة الزيتون إلى اليونان وقرطاج وليبيا في القرن الثامن والعشرين قبل الميلاد، بعد أن انتشرت غربًا على يد الفينيقيين.[7] حتى حوالي عام ١٥٠٠ قبل الميلاد، كانت المناطق الساحلية الشرقية للبحر الأبيض المتوسط الأكثر زراعةً.[citation needed]

تشير الدلائل أيضًا إلى أن زراعة الزيتون كانت تُزرع في جزيرة كريت منذ عام ٢٥٠٠ قبل الميلاد. يعود تاريخ أقدم قوارير زيت الزيتون الباقية إلى عام ٣٥٠٠ قبل الميلاد (العصر المينوي المبكر)، مع أنه يُفترض أن إنتاج زيت الزيتون بدأ قبل عام ٤٠٠٠ قبل الميلاد.[8]

من المؤكد أن أشجار الزيتون زُرعت في كريت بحلول أواخر العصر المينوي (١٥٠٠ قبل الميلاد)، وربما يعود ذلك إلى أوائل العصر المينوي.[9] ازدادت زراعة أشجار الزيتون في كريت كثافةً في فترة ما بعد القصور، ولعبت دورًا هامًا في اقتصاد الجزيرة، كما فعلت في جميع أنحاء البحر المتوسط.[10]

وفي وقت لاحق، ومع إنشاء المستعمرات اليونانية في أجزاء أخرى من البحر المتوسط، تم إدخال زراعة الزيتون إلى أماكن مثل إسبانيا واستمرت في الانتشار في جميع أنحاء الإمبراطورية الرومانية.[7]

تم إدخال أشجار الزيتون إلى الأمريكتين في القرن السادس عشر، عندما بدأت الزراعة في مناطق ذات مناخ مشابه لمناخ البحر الأبيض المتوسط، مثل تشيلي والأرجنتين وكاليفورنيا.[7]

تشير الدراسات الجينية الحديثة إلى أن الأنواع التي يستخدمها المزارعون المعاصرون تنحدر من مجموعات برية متعددة، ولكن التاريخ التفصيلي للتدجين غير معروف.[11]

التجارة والإنتاج

Archaeological evidence in Galilee shows that by 6000 BC olives were being turned into olive oil[12] and in 4500 BC at a now-submerged prehistoric settlement south of Haifa.[13]

Olive trees and oil production in the Eastern Mediterranean can be traced to archives of the ancient city-state Ebla (2600–2240 BC), which were located on the outskirts of Aleppo. Here, some dozen documents dated 2400 BC describe the lands of the king and the queen. These belonged to a library of clay tablets perfectly preserved by having been baked in the fire that destroyed the palace. A later source is the frequent mentions of oil in the Tanakh.[14]

Dynastic Egyptians before 2000 BC imported olive oil from Crete, Syria, and Canaan, and oil was an important item of commerce and wealth. Remains of olive oil have been found in jugs over 4,000 years old in a tomb on the island of Naxos in the Aegean Sea. Sinuhe, the Egyptian exile who lived in northern Canaan c.1960 BC, wrote of abundant olive trees.[15] The Minoans used olive oil in religious ceremonies. The oil became a principal product of the Minoan civilization, where it is thought to have represented wealth.[16]

Olive oil was also a major export of Mycenaean Greece (c. 1450–1150 BC).[17][7] Scholars believe the oil was made by a process where olives were placed in woven mats and squeezed. The oil was collected in vats. This process was known from the Bronze Age, was used by the Egyptians, and continued to be used through the Hellenistic period.[7] In the Iron Age, settlements in and around the Judaean Lowlands, including Ekron, Timnah, and Gezer, emerged as key hubs for olive oil production and commerce.[18] Evidence from the Samaria ostraca, discovered in the capital of the Kingdom of Israel, includes a reference to "washed oil," a term believed to refer to virgin olive oil.[18]

The importance of olive oil as a commercial commodity increased after the Roman conquest of Egypt, Greece, and Asia Minor, which led to more trade along the Mediterranean. Olive trees were planted throughout the entire Mediterranean basin during the evolution of the Roman Republic and Empire. According to the historian Pliny the Elder, Italy had "excellent olive oil at reasonable prices" by the 1st century AD—"the best in the Mediterranean".[citation needed] As olive production expanded in the 5th century AD the Romans began to employ more sophisticated production techniques such as the olive press and trapetum (pictured left).[7] Many ancient presses still exist in the Eastern Mediterranean region, and some dating to the Roman period are still used today.[19] Productivity was greatly improved by Joseph Graham's development of the hydraulic pressing system in 1795.[7]

الرمزية والأساطير

لطالما كانت شجرة الزيتون رمزًا للسلام بين الأمم. ولعبت دورًا دينيًا واجتماعيًا في الأساطير اليونانية، وخاصةً فيما يتعلق بمدينة أثينا، التي سُميت تيمنًا بالإلهة أثينا لأن هديتها من شجرة زيتون كانت تُعتبر أثمن من هبة منافسها بوسيدون من نبع ملح.[7]

استخلاصه

يستخلص بعصر ثمار الزيتون الناضجة في مطحنة ثم تضغط الكتلة اللزجة المتبقية فنحصل على أفخر أنواع الزيتون ويعرف بزيت العذراء Virigin Oil نعود للكتلة المتبقية ونضيف لها ماء ثم نعصر من جديد فنحصل على زيت من الدرجة الثانية أما في آخر مرحلة حيث لا يعود بالامكان استخلاص أي قطرة زيت نضيف للكتلة المتبقية ثنائي سلفات الكربون.

فوائد زيت الزيتون

| القيمة الغذائية لكل 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| الطاقة | 3،701 kJ (885 kcal) |

0 g | |

100 g | |

| مشبع | 14 g |

| أحادي عدم التشبع | 73 g |

| متعدد عدم التشبع | 11 g <1.5 g 3.5-21g |

0 g | |

| الڤيتامينات | |

| ڤيتامين E | (93%) 14 mg |

| ڤيتامين ك | (59%) 62 μg |

100 g olive oil is 109 ml | |

| |

| Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

وتعتبر شجرة ثمار الزيتون (Olea europaea) مصدر غذاء طيب ومقاومة لأمراض النباتات. وعصير أوراق الزيتون أو خلاصتها أو مسحوقها يعتبران مضادا حيويا ومضادا للفيروسات قويا كما أنها مقوية لجهاز المناعة الذي يحمي الجسم من الأمراض والعدوي وتقلل من أعراض فيروسات البرد والجديري والهربس. والأوراق بها مادة Oleuropein (حامض دهني غير مشبع) مضادة قوية للجراثيم كالفيروسات والطفيليات وبكتريا الخميرة والبروتوزوا, حيث تمنع نموها.

يعتبر زيت الزيتون المحضر من ثمار الزيتون بالعصر علي البارد (يطلق عليه زيت عذري) أو بالمذيبات. ويعالج الحساسية المتكررة ومشاكل الجهاز الهضمي وملين خفيف. ويعالج تورم العقد الليمفاوية والوهن وتورم المفاصل وآلامها وقلة الشهية والجيوب الأنفية المنتفخة ومشاكل الجهاز التنفسي ولاسيما الربو وقرح الجلد والهرش والقلق ومشاكل العدوي ووهن العضلات, وكان يستخدمها الإغريق لتنظيف الجروح والتئامها, وهي مضادة للبكتريا والفطريات والطفيليات والفيروسات وتفيد في البواسير ومدرة خفيفة للبول لهذا كانوا يتناولونها لعلاج النقرس وتخفيض السكر قي الجسم وضغط الدم وتقوية جهاز المناعة ولهذا تفيد في علاج الأمراض الفيروسية ومرض الذئبة والإلتهاب الكبدي والإيدز ومشاكل البروستاتا والصدفية وعدوي المثانة وتحضر خلاصة لهذا الغرض.

الأوراق بها مادة Oleuropein الفعالة وهي مضادة للأكسدة وتزيل تصلب الشرايين وتعيد للأنسجة حيويتها لوجود فيتامين E, والزيتون به أيضا 3مضادات أكسدة قوية hydroxytyrosol, vanillic acid, and verbascoside التي تفيد في علاج الروماتويد (إالتهاب المفاصل). وتناول خلاصة الأوراق قد تسبب أعراض شبيهة بنزلة البرد لأنها تهاجم الفيروسات لكن هذه الحالة تزول بعد عدة أيام مع تناولها. وثمار الزيتون الخضراء هي الثمار الغير ناضجة والبنية هي ثمار ناضجة .

ويحتوي الزيت علي نسبة عالية من الدهون الغير مشبعة وفيتامينE,k وفينولات متعددة وكلوروفيل وصبغة pheophytin وsterols و squalene ومركبات تكسبه الرائحة والنكهة. وزيث الزيتون لأنه به زيوت غير مشبعة لايتأكسد (يزنخ)لأنها مكونة من حامض أوليك oleic acid التي تقلل نسبة الكولسترول منخفض الكثافة LDL-cholesterol الضار وتزيد نسبة الكولسترول مرتفع الكثافة HDL-cholesterol النافع وهذه الدهون جعلت شعوب البحر الأبيض المتوسط التي تتناول زيت الزيتون بوفراة, لاتصاب بأمراض الأوعية القلبية, كما يقلل الإصابة بسرطان الثدي. ووجود الفينولات وفيتامين E وغيرهما من مضادات الأكسدة الطبيعية يمنع تأكسد الدهون وتحاشي تكوين الجذور الحرة Free Radicals التي تتلف الخلايا بالجسم. ووجود الرائحة والكلوروفيل والنكهة الطبيعية وصبغة pheophytin تجعل الزيت يزيد من إفرازات المعدة ويسهل عملية إمتصاص المواد المضادة للأكسدة الطبيعية التي تحمي أنسجة الجسم من التلف .ونسبة فيتامين E كافية وأعلي نسبة موجودة في أي زيت نباتي. لهذا تحافظ علي منع تأكسده بالتخزين. ولون الزيت له صلة بوجود الكلوروفيل وصبغة pheophytin والكاروتينويدات Carotenoids ووجود هذه الألوان يعتمد علي زراعة الزيتون وموعد جمعه والتربة والمناخ ونضج ثمار الزيتون وطريقة عصرها. لهذا نجد أن زيت الزيتون يقي الجسم من المواد المؤكسدة وتصلب الشرايين ويمنع تكوين حصوات المرارة ويمنع الإلتهابات المعدية ويبطن المعدة للجماية من القرحة وينشط إفراو الهورمونات بالبنكرياس ويساعد علي إمتصاص الغذاء بالجهاز الهضمي ولا سيما المعادن والفيتامينات. ويعالج الإمساك. ولوجود مادة أوليات يوفرة في ويت الزيتون نجده يساعد علي ترسيب المعادن في العظام ويقويها ولاسيما لدي الأطفال وكبار السن ويساعد علي تنمية المخ والجهاز العصبي ويحمي الجسم من العدوي ويساعد في نموه ويجدد خلاياه ويمنع تقلص المعدة. مطري للجلد ومغذ له لوجود فيتامينات E و Aو Kو B. ويفضل شرب ماء بوفرة 8كوب مع تناوله. يتناول مع السلاطة أو يشرب أو يوضع علي الفول أو الجبن أو للتحمير . ويحتوي زيت الزيتون البكر (العذري) علي مضدات أكسدة كفيتامين Kو A وب و E, وبوليفينولات polyphenols. ودهون حمضية أحادية غير مشبعة ونافعة ولا ترفع نسبة الكولسترول الضار bad cholesterol (LDL cholesterol). وملعقة شوربة زيت زيتون (14جرام) تعطي 120 سعر حراري وبها دهون أحادية غير مشبعة 77% و 9% دهون مشبعة والباقي دهون نباتية.

استخداماته الصيدلانية

يدخل زيت الزيتزن في صناعة مستحضرات التجميل مثل الكريمات CreamالمروخاتLinimentsاللصاقات Plasters وفعال في تحضير المستحلبات Emulsionsوفي صناعة الصابون و مستحضرات العناية بالشعر مثل شامبو-بلسم ويدخل أيضاً في صناعة كريم التسمير Sun-tan(اكتساب السمرة) يدخل في صناعة الكبسولات و المحاليل الفموية ويدخل كسواغ زيتي في الحقن الزيتية يستخدم موضعياً في الجل الدسم Lipogels مثل نيكوتينات الميتيل ويستخدم كمرطب لشمع الأذن Ear wax (الصملاخ) يستخدم بالمشاركة مع زيت فول الصويا في مستحلبات تعطى للرضع الذين ولدو قبل أوانهم (Pre-term infants) في الصناعات الغذائية والطبخ ويحوي زيت الزيتون على مضادات أكسدة معينة ويضاف له مضادات أكسدة أيضاً

الأصناف

هناك العديد من أصناف الزيتون، ولكل منها نكهة وملمس ومدة صلاحية معينة تجعلها أكثر أو أقل ملاءمة لتطبيقات مختلفة، مثل الاستهلاك البشري المباشر على الخبز أو في السلطات، أو الاستهلاك غير المباشر في الطبخ المنزلي أو تقديم الطعام، أو الاستخدامات الصناعية مثل علف الحيوانات أو التطبيقات الهندسية.[20] During the stages of maturity, olive fruit changes color from green to violet, and then black. Olive oil taste characteristics depend on the stage of ripeness at which olive fruits are collected.[20]

هناك عدة أنواع من زيت الزيتون ومن أشهرها:

- زيت الزيتون البكر VIRGIN OLIVE OIL هو الزيت المستخلص من الزيتون دون احداث أي تغيرات في صفات الزيت.

- زيت الزيتون المكرر REFINED OLIVE OIL يحصل عليه من الزيت البكر بعد تعريضه لعمليات التكرير.

- زيت الزيتون الصافي PURE OLIVE OIL وهو يتألف من زيت الزيتون البكر وزيت الزيتون المكرر.

الاستخدامات

الاستخدام في الطهي

Olive oil is an important cooking oil in countries surrounding the Mediterranean, and it forms one of the three staple food plants of Mediterranean cuisine, the other two being wheat (as in pasta, bread, and couscous), and the grape, used as a dessert fruit and for wine.[21]

Extra virgin olive oil is mostly used raw as a condiment and as an ingredient in salad dressings. If uncompromised by heat, the flavor is stronger. It can also be used for sautéing.

When extra virgin olive oil is heated above 210–216 °C (410–421 °F), depending on its free fatty acid content, the unrefined particles within the oil are burned. This leads to a deteriorated taste. Refined olive oils are suited for deep frying because of the higher smoke point and milder flavour.[22] Extra virgin oils have a smoke point around 180–215 °C (356–419 °F),[23] with higher-quality oils having a higher smoke point,[24] whereas refined light olive oil has a smoke point up to 230 °C (446 °F).[23] That they can be used for deep frying is contrary to the common misconception that there are no olive oils with a smoke point as high as many other vegetable oils. In the misconception, heating at these high temperatures is theorised to impact taste or nutrition.[25][26]

الاستخدام الديني

رافقت شجرة الزيتون الإنسان منذ أن خلق، فلقد اكتشف الجيولوجيون وعلماء الآثار بقايا أشجار وحبوب زيتون، وتعود إلى المرحلة التى بدأ فيها الإنسان يصقل الحجر ويبني الأكواخ ويزرع الأرض. ويقال أن البابليون هم أول من زرع شجرة الزيتون بشكلها الحالي عن طريق التطعيم.

وفى الإسلام زيت الزيتون يمثل نعمة من الله وذكر في قوله تعالى: (الله نور السموات والأرض مثل نوره كمشكاة فيها مصباح المصباح في زجاجة الزجاجة كأنها كوكب دري يوقد من شجرة مباركة زيتونة لا شرقية ولا غربية يكاد زيتها يضئ ولو لم تمسسه نار …) سورة النور الآية (35)

وذكر في كافة الأديان الأخرى والحضارات القديمة. فجعلت الحماحة التى أرسلها نوح من شجرة الزيتون رمزاً للسلام، واليونانيون جعلوها رمزاً للقوة والعظمة والحكمة والنصر، في حين جعلها المسيحيين رمزاً للدين والآلام لأن السيد المسيح تألم على جبل الزيتون وأخيراً جعلت رمزاً للصحة والطعام اللذيذ، ولقد تضاعفت الدراسات على منافع زيت الزيتون منذ عدة عقود لأن الطلب والبحث عنه ازداد والدول المنتجة له (إيطاليا، فرنسا، أسبانيا، اليونان) تبذل جهوداً لكي يكون هذا الزيت أشهى وألذ وأصفى، وكذلك بسبب أنه يقدم الغذاء الشافي. يبلغ عدد أنواع أشجار الزيتون حوالى مئة وخمسين نوعاً، ويتراوح ارتفاعها بين خمسة أمتار واثني عشر متراً، وهي تحتاج إلى مناخ معتدل في فصل الشتاء وجاف في الصيف، وإلى كمية كبيرة من الأمطار في فصلي الخريف والربيع، وهي ظروف مناخية لا تتوفر إلا في محيط البحر المتوسط، وتتمتع شجرة الزيتون بأوراق دائمة الخضرة، تتجدد كل ثلاث سنوات وهي تنمو ببطء وكأنها تستخلص فوائد الأرض على مهل وبتركيز. تذكر على ملصقات زيت الزيتون ماركة الزيت ومصدره وأحياناً اسم المنطقة التى انتج فيها وأحياناً جنس الزيتون المستخدم ودرجة نضجه (زيتون أخضر أو أسود) فضلاً عن طريقة عصره أو عبارة (زيتون منزوع النواة) ولكن ما يذكر بشكل خاص هو نوعية الزيت أي: زيت زيتون صاف….

لقد أكتشف أن قدماء المصريين كانوا يستعملون زيت الزيتون في التحنيط ويعتبرون أن غصن الزيتون رمز للقوة الأبدية وكان الإغريق يجدلون غصون الزيتون الغضة كأكاليل توضع فوق رؤوس الفائزين في الدورات الأولمبية.

المسيحية

The Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Anglican churches use olive oil for the oil of catechumens (used to bless and strengthen those preparing for baptism) and oil of the sick (used to confer the Sacrament of anointing of the sick or extreme unction). Olive oil mixed with a perfuming agent such as balsam is consecrated by bishops as sacred chrism, which is used to confer the sacrament of confirmation (as a symbol of the strengthening of the Holy Spirit), in the rites of baptism and the ordination of priests and bishops, in the consecration of altars and churches, and, traditionally, in the anointing of monarchs at their coronation.

Eastern Orthodox Christians still use oil lamps in their churches, home prayer corners, and cemeteries. A vigil lamp consists of a votive glass filled with olive oil, floating on a half-inch of water. The glass has a metal holder that hangs from a bracket on the wall or sits on a table. A cork float with a lit wick floats on the oil. To douse the flame, the float is carefully pressed down into the oil. Makeshift oil lamps can easily be made by soaking a cotton ball in olive oil and forming it into a peak. The peak is lit and then burns until all the oil is consumed, whereupon the rest of the cotton burns out. Olive oil is a usual offering to churches and cemeteries.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints uses virgin olive oil that the priesthood has blessed for anointing the sick.[27]

اليهودية

In Jewish observance, olive oil was the only fuel allowed to be used in the seven-branched menorah in the Mishkan service during the Exodus of the Tribes of Israel from Egypt, and later in the permanent Temple in Jerusalem. It was obtained by using only the first drop from a squeezed olive and consecrated for use only in the Temple by the priests and stored in special containers. In modern times, although candles can be used to light the menorah at Hanukkah, oil containers are preferred to imitate the original menorah.[28]

In Judaism of Ancient Israel, olive oil was also used to prepare the holy anointing oil used for priests, kings, prophets, and others.[29]

أخرى

Olive oil is also a natural and safe lubricant, and can be used to lubricate kitchen machinery (grinders, blenders, cookware, etc.). It can also be used for illumination (oil lamps) or as the base for soaps and detergents.[30] Some cosmetics also use olive oil as their base,[31] and it can be used as a substitute for machine oil.[32][33][34] Olive oil has also been used as both solvent and ligand in the synthesis of cadmium selenide quantum dots.[35]

The Ranieri Filo della Torre is an international literary prize for writings about extra virgin olive oil. It yearly honors poetry, fiction, and non-fiction about extra virgin olive oil.

الاستخراج

هذا القسم يحتاج المزيد من الأسانيد للتحقق. (June 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

يُنتَج زيت الزيتون بطحن الزيتون واستخلاصه ميكانيكيًا أو كيميائيًا. عادةً ما يُنتج الزيتون الأخضر زيتًا أكثر مرارة، بينما يُمكن أن يُنتج الزيتون الناضج جدًا زيتًا به عيوب تخمير. لذا، للحصول على زيت زيتون جيد، يُراعى التأكد من نضج الزيتون تمامًا. تتم العملية بشكل عام كما يلي:

- يتم طحن الزيتون إلى عجينة باستخدام أحجار الرحى الكبيرة (الطريقة التقليدية)، أو المطرقة، أو الشفرة، أو مطحنة الأقراص (الطريقة الحديثة).

- إذا تم طحن معجون الزيتون باستخدام أحجار الرحى، فإنه يبقى عمومًا تحت الأحجار لمدة 30 إلى 40 دقيقة. قد تؤدي عملية الطحن الأقصر إلى الحصول على معجون أكثر خشونة ينتج زيتًا أقل وله طعم أقل نضجًا؛ قد تؤدي العملية الأطول إلى زيادة أكسدة المعجون وتقليل النكهة. بعد الطحن، يُنشر معجون الزيتون على أقراص ليفية، مكدسة فوق بعضها البعض في عمود، ثم توضع في المكبس. ثم يُطبق الضغط على العمود لفصل السائل النباتي عن المعجون. لا يزال هذا السائل يحتوي على كمية كبيرة من الماء. تقليديًا، كان يتم فصل الزيت عن الماء عن طريق الجاذبية (الزيت أقل كثافة من الماء). تم استبدال عملية الفصل البطيئة للغاية هذه بالطرد المركزي، وهو أسرع بكثير وأكثر شمولاً. تحتوي أجهزة الطرد المركزي على مخرج واحد للجزء المائي (الأثقل) وآخر للزيت. يجب ألا يحتوي زيت الزيتون على آثار كبيرة من الماء النباتي، لأن هذا يسرع من عملية التحلل العضوي بواسطة الكائنات الحية الدقيقة. الفصل في معاصر الزيت الأصغر ليس مثاليًا دائمًا؛ وهكذا، يمكن العثور على رواسب مائية صغيرة تحتوي على جزيئات عضوية في قاع زجاجات الزيت.

- تُحوّل مطاحن الزيتون الحديثة الزيتون إلى معجون في ثوانٍ. بعد الطحن، يُحرّك المعجون ببطء لمدة ٢٠ إلى ٣٠ دقيقة أخرى في وعاء مُخصّص (مُلَكْس)، حيث تتجمع قطرات الزيت المجهرية في قطرات أكبر، مما يُسهّل الاستخلاص الميكانيكي. ثم يُضغط المعجون بالطرد المركزي، ويُفصل الماء عن الزيت في طرد مركزي ثانٍ كما هو موضح سابقًا.

يُسمّى الزيت المُنتَج بوسائل فيزيائية (ميكانيكية) فقط، كما هو موضح أعلاه، زيتًا بكرًا.[36] زيت الزيتون البكر الممتاز هو زيت زيتون بكر يلبي معايير كيميائية وحسية عالية (حموضة حرة منخفضة، (مع وجود عيوب حسية قليلة أو معدومة). يعتمد زيت الزيتون البكر الممتاز عالي الجودة بشكل أساسي على الظروف الجوية المواتية؛ فالجفاف خلال مرحلة الإزهار، على سبيل المثال، قد يؤدي إلى انخفاض جودة الزيت (البكر). تُنتج أشجار الزيتون إنتاجًا جيدًا كل عامين، لذا يُنتج محصول أكبر في أعوام متناوبة (السنة التي تفصل بين العامين هي التي يقل فيها إنتاج الشجرة). ومع ذلك، تبقى الجودة معتمدة على الطقس.

- في بعض الأحيان، يُصفّى الزيت المُنتَج لإزالة الجزيئات الصلبة المتبقية التي قد تُقلّل من مدة صلاحية المنتج. قد تُشير الملصقات إلى أن الزيت "لم يُصفَّ"، مما يُشير إلى اختلاف في الطعم. عادةً ما يكون زيت الزيتون الطازج غير المُصفّى ذو مظهرٍ غائم قليلاً، ولذلك يُسمّى أحيانًا "زيت الزيتون الغائم". كان هذا النوع من زيت الزيتون شائعًا فقط بين صغار المُنتجين، ولكنه أصبح الآن رائجًا، تماشيًا مع طلب المستهلكين على المنتجات التي يُعتقد أنها أقل معالجة. لكن عمومًا، يُفضّل زيت الزيتون المُصفّى إذا لم يُتذوق أو يُستهلك بعد الإنتاج مباشرةً: "يُصرّح بعض المُنتجين بأنّ زيوت الزيتون البكر الممتاز لا تحتاج إلى ترشيح، ولكنّ الترشيح يُضرّ بجودة الزيت. ويُعتبر هذا الرأي خاطئًا، وربما يكون نتيجةً لسوء تطبيق هذه العملية. في الواقع، تحتوي الجسيمات الدقيقة العالقة في زيت الزيتون البكر، حتى بعد عملية التصفية بالطرد المركزي الأكثر فعالية، على ماء وإنزيمات قد تُضعف استقرار الزيت وتُفسد نكهته الحسية.... يُحسّن الترشيح من استقرار زيت الزيتون البكر الممتاز وجاذبيته. إذا لم تُزل الجسيمات العالقة، فإنها تتكتل وتتكتل ببطء، مُشكّلةً رواسب في قاع حاويات التخزين. وتظل هذه الرواسب عُرضةً لخطر التلف الإنزيمي، وفي أسوأ الأحوال، لنمو الكائنات الدقيقة اللاهوائية، مما يُفاقم التلف ويُشكّل خطرًا صحيًا.... يُوصى بإجراء الترشيح في أقرب وقت ممكن. قدر الإمكان بعد الفصل بالطرد المركزي والتشطيب.[37]

بلاد الشام القديمة

In the ancient Levant, three methods were used to produce different grades of olive oil.[38] The finest oil was produced from fully developed and ripe olives harvested solely from the apex of the tree,[39] and lightly pressed, "for what flows from light pressure is very sweet and very thin".[40] The remaining olives are pressed with a heavier weight,[40] and vary in ripeness.[39] Inferior oil is produced from unripe olives that are stored for extended periods until they grow soft or begin to shrivel to become more fit for grinding.[41] Others are left for extended periods in pits in the ground to induce sweating and decay before they are ground.[42] According to the Geoponica, salt and a little nitre are added when oil is stored.[40]

In countries of the levant, a sharp-tasting green oil was sometimes extracted from unripe olives, known in medieval times as anpeqinonقالب:Verify inline (Ancient Greek: ὀμφάκιον, ὀμφάχινον; عربية: زيت الأنفاق), being a corruption of the Latin words oleum omphacium and used in cuisine and in medicine.[43][44][45] Today, this oil is called "virgin oil" in English.[43]

معالجة ثفل الزيتون

The remaining semi-solid waste, called pomace, retains a small quantity (about 5–10%) of oil that cannot be extracted by further pressing, but only with chemical solvents. This is done in specialized chemical plants, not in the oil mills. The resulting oil is named pomace oil.[46]

Handling of olive waste is an environmental challenge because the wastewater, which amounts to millions of tons (billions of liters) annually in the European Union, has low biodegradability, is toxic to plants, and cannot be processed through conventional water treatment systems.[46] Traditionally, olive pomace would be used as compost or developed as a possible biofuel, although these uses introduce concern due to chemicals present in the pomace.[46] A process called "valorization" of olive pomace is under research and development, consisting of additional processing to obtain value-added byproducts, such as animal feed, food additives for human products, and phenolic and fatty acid extracts for potential human use.[46]

السوق العالمي

البلدان المنتجة والمستهلكة الرئيسية هي:

| البلد | الانتاج (2005[47]) | الاستهلاك (2005[47]) | الاستهلاك السنوي للفرد (كج)[48] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| اسبانيا | 36% | 20% | 13.62 | |

| تونس | 32% | 25% | 11.1 | |

| إيطاليا | 25% | 30% | 12.35 | |

| اليونان | 18% | 9% | 23.7 | |

| تركيا | 5% | 2% | 1.2 | |

| سوريا | 4% | 3% | 6 | |

| المغرب | 3% | 2% | 1.8 | |

| البرتغال | 1% | 2% | 7.1 | |

| الولايات المتحدة | 0% | 8% | 0.56 | |

| فرنسا | 0% | 4% | 1.34 | |

| لبنان | 0% | 3% | 1.18 |

الإنتاج

| 665,709 | |

| 331,038 | |

| 313,300 | |

| 302,400 | |

| 235,200 | |

| 189,423 | |

| 181,500 | |

| 137,753 | |

World |

2,743,216 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[1] | |

In 2022, world production of olive oil was 2.7 million tonnes, led by Spain with 24% of the total (table). Other major producers were Italy, Greece, and Turkey (table).

Villacarrillo, Jaén, Andalucía, Spain, is a center of olive oil production. Spain's olive oil production derives 75% from the region of Andalucía, particularly within Jaén province which produces 70% of the olive oil in Spain.[49] The world's largest olive oil mill (almazara, in Spanish), capable of processing 2,500 tonnes of olives per day, is in the town of Villacarrillo, Jaén.[49]

Italian major producers are the regions of Calabria and, above all, Apulia. Many PDO and PGI extra-virgin olive oils are produced in these regions. Extra-virgin olive oil is also produced in Tuscany,[50] in cities including Lucca, Florence, and Siena, which are also included in the association of Città dell'Olio.[51] Italy imports about 65% of Spanish olive oil exports.[52]

الاستهلاك العالمي

Greece has the highest per capita consumption of olive oil worldwide, around 24 liters per year.[53] Consumption in Spain is 15 liters; Italy 13 liters;[53] and Israel, around 3 liters.[54] Canada consumes 1.5 liters and the US 1 liter.[53]

اللوائح

The International Olive Council (IOC) is an intergovernmental organisation of states that produce olives or products derived from olives, such as olive oil. The IOC officially governs 95% of international production and influences the rest. The EU regulates the use of different protected designation of origin labels for olive oils.[55]

The United States is not a member of the IOC and is not subject to its authority, but on October 25, 2010, the U.S. Department of Agriculture adopted new voluntary olive oil grading standards that closely parallel those of the IOC, with some adjustments for the characteristics of olives grown in the U.S.[56] U.S. Customs regulations on "country of origin" state that if a non-origin nation is shown on the label, then the real origin must be shown on the same side of the label in letters of comparable size, so as not to mislead the consumer.[57][58] Yet most major U.S. brands continue to put "imported from Italy" on the front label in large letters and other origins on the back in very small print.[59] "In fact, olive oil labeled 'Italian' often comes from Turkey, Tunisia, Morocco, Spain, and Greece."[60] This makes it unclear what percentage of the olive oil is really of Italian origin.

الدرجات التجارية

All production begins by crushing or pressing the olive fruit to transform it into olive paste. This paste is malaxed (slowly churned or mixed) to allow the microscopic oil droplets to agglomerate. The oil is then separated from the watery matter and fruit pulp with the use of a press (traditional method) or centrifugation (modern method). The residue that remains after pressing or centrifugation can also produce a small amount of oil, called pomace.

One parameter used to characterise an oil is its acidity.[61] In this context, "acidity" is not chemical acidity in the sense of pH, but the percent (measured by weight) of free oleic acid. Olive oil acidity is a measure of the hydrolysis of the oil's triglycerides: as the oil degrades and becomes oxidized, more fatty acids are freed from the glycerides, increasing the level of free acidity and thereby increasing hydrolytic rancidity.[62] Rancidity not only impacts the taste and color but also its nutritional value.[63]

Another measure of the oil's chemical degradation is the peroxide value,[64] which measures the degree to which the oil is oxidized by free radicals, leading to oxidative rancidity. Phenolic acids present in olive oil also add acidic sensory properties to aroma and flavor.[65]

The grades of oil extracted from the olive fruit can be classified as:

- Virgin means the oil was produced by the use of mechanical means only, with no chemical treatment. The term virgin oil with reference to production method includes all grades of virgin olive oil, including extra virgin, virgin, ordinary virgin and Lampante virgin olive oil products, depending on quality (see below).

- Lampante virgin oil is olive oil extracted by virgin (mechanical) methods but not suitable for human consumption without further refining; "lampante" is the attributive form of "lampa", the Italian word for "lamp", referring to the use of such oil in oil lamps. Lampante virgin oil can be used for industrial purposes, or refined (see below) to make it edible.[66]

- Refined olive oil is olive oil obtained from any grade of virgin olive oil by refining methods that do not lead to alterations in the initial glyceridic structure. The refining process removes color, odor, and flavour from the olive oil, and leaves behind a very pure form of olive oil that is tasteless, colorless, odorless, and extremely low in free fatty acids. Olive oils sold as the grades extra virgin olive oil and virgin olive oil therefore cannot contain any refined oil.[66]

- Crude olive pomace oil is the oil obtained by treating olive pomace (the leftover paste after the pressing of olives for virgin olive oils) with solvents or other physical treatments, to the exclusion of oils obtained by re-esterification processes and of any mixture with other kinds of oils. It is then further refined into refined olive pomace oil and once re-blended with virgin olive oils for taste, is then known as olive pomace oil.[66]

المجلس الدولي للزيتون

In countries that adhere to the standards of the International Olive Council,[67] as well as in Australia, and under the voluntary United States Department of Agriculture labeling standards in the United States:

Extra virgin olive oil is the highest grade of virgin olive oil derived by cold mechanical extraction without use of solvents or refining methods.[66][68] It contains no more than 0.8% free acidity, and is judged to have a superior taste, having some fruitiness and no defined sensory defects.[69] Extra virgin olive oil accounts for less than 10% of oil in many producing countries; the percentage is far higher in some Mediterranean countries.

The International Olive Council requires the median of the fruity attribute to be higher than zero for a given olive oil in order to meet the criteria of extra virgin olive oil classification.

Virgin olive oil is a lesser grade of virgin oil, with free acidity of up to 2.0%, and is judged to have a good taste, but may include some sensory defects.

Refined olive oil is virgin oil refined using charcoal and other chemical and physical filters, methods which do not alter the glyceridic structure. It has a free acidity, expressed as oleic acid, of not more than 0.3 grams per 100 grams (0.3%), and its other characteristics correspond to those fixed for this category in this standard. It is obtained by refining virgin oils to eliminate high acidity or organoleptic defects. Oils labeled as pure olive oil or olive oil are primarily refined olive oil, with a small addition of virgin oil for taste.

Olive pomace oil is refined pomace olive oil, often blended with some virgin oil. It is fit for consumption, but may not be described simply as olive oil. It has a more neutral flavor than pure or virgin olive oil, making it less desirable to users concerned with flavor; however, it has the same fat composition as regular olive oil, giving it the same health benefits. It also has a high smoke point, and consequently is widely used in restaurants and home cooking in some countries.

الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

The United States is not a member of the IOC and does not implement its grades, but on October 25, 2010, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) established Standards for Grades of Olive Oil and Olive-Pomace Oil which closely parallel the IOC standards:[70][71]

- U.S. extra virgin olive oil for oil with excellent flavor and odor and free fatty acid content of not more than 0.8 g per 100 g (0.8%);

- U.S. virgin olive oil for oil with reasonably good flavor and odor and free fatty acid content of not more than 2 g per 100 g (2%);

- U.S. virgin olive oil Not Fit For Human Consumption Without Further Processing is a virgin (mechanically-extracted) olive oil of poor flavor and odor, equivalent to the IOC's lampante oil;

- U.S. olive oil is a mixture of virgin and refined oils;

- U.S. refined olive oil is an oil made from refined oils with some restrictions on the processing.

These grades are voluntary. Certification is available, for a fee, from the USDA.[71]

In 2014, California adopted a set of olive oil standards for olive oil made from California-grown olives. The California Department of Food and Agriculture Grade and Labeling Standards for Olive Oil, Refined-Olive Oil, and Olive-Pomace Oil are mandatory for producers of more than 5,000 gallons of California olive oil. This joins other official state, federal, and international olive oil standards.[72]

Several olive producer associations, such as the North American Olive Oil Association and the California Olive Oil Council, also offer grading and certification within the United States.[73][74] Oleologist Nicholas Coleman suggests that the California Olive Oil Council certification is the most stringent of the voluntary grading schemes in the United States.[75]

Country of origin can be established by one or two-letter country codes printed on the bottle or label. Country codes include I=Italy, GR=Greece, E=Spain, TU=Tunisia, MA=Morocco, CL=Chile, AG=Argentina, AU=Australia.

صياغة الملصق

- Different names for olive oil indicate the degree of processing the oil has undergone as well as the quality of the oil. Extra virgin olive oil is the highest grade available, followed by virgin olive oil. The word "virgin" indicates that the olives have been pressed to extract the oil; no heat or chemicals have been used during the extraction process, and the oil is pure and unrefined. Virgin olive oils contain the highest levels of polyphenols, antioxidants that have been linked with better health.[76]

- Olive Oil, which is sometimes denoted as being "Made from refined and virgin olive oils" is a blend of refined olive oil with a virgin grade of olive oil.[66] Pure, Classic, Light and Extra-Light are terms introduced by manufacturers in countries that are non-traditional consumers of olive oil for these products to indicate both their composition of being only 100% olive oil, and also the varying strength of taste to consumers. Contrary to a common consumer belief, they do not have fewer calories than extra virgin oil, as implied by the names.[77]

- Cold pressed or Cold extraction means "that the oil was not heated over a certain temperature (usually 27 °C (80 °F)) during processing, thus retaining more nutrients and undergoing less degradation".[78] The difference between Cold Extraction and Cold Pressed is regulated in Europe, where the use of a centrifuge, the modern method of extraction for large quantities, must be labelled as Cold Extracted, while only a physically pressed olive oil may be labelled as Cold Pressed. In many parts of the world, such as Australia, producers using centrifugal extraction still label their products as Cold Pressed.

- First cold pressed means "that the fruit of the olive was crushed exactly one time – i.e., the first press. The cold refers to the temperature range of the fruit at the time it is crushed".[79] In Calabria (Italy) the olives are collected in October. In regions like Tuscany or Liguria, the olives collected in November and ground, often at night, are too cold to be processed efficiently without heating. The paste is regularly heated above the environmental temperatures, which may be as low as 10–15 °C, to extract the oil efficiently with only physical means. Olives pressed in warm regions like Southern Italy or Northern Africa may be pressed at significantly higher temperatures, although not heated. While it is important that the pressing temperatures be as low as possible (generally below 25 °C) there is no international reliable definition of "cold pressed".

Furthermore, there is no "second" press of virgin oil, so the term "first press" means only that the oil was produced in a press vs. other possible methods. - Protected designation of origin (PDO) and protected geographical indication (PGI) refer to olive oils with "exceptional properties and quality derived from their place of origin as well as from the way of their production".[80]

- The label may indicate that the oil was bottled or packed in a stated country. This does not necessarily mean that the oil was produced there. The origin of the oil may sometimes be marked elsewhere on the label; it may be a mixture of oils from multiple countries.[59]

- The U.S. Food and Drug Administration permitted a claim on olive oil labels stating: "Limited and not conclusive scientific evidence suggests that eating about two tablespoons (23 g) of olive oil daily may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease."[81]

الغش

كانت هناك مزاعم، لا سيما في إيطاليا وإسبانيا، بأن اللوائح التنظيمية قد تكون أحيانًا متساهلة وفاسدة.[82] يُزعم أن شركات الشحن الكبرى تغش زيت الزيتون بشكل روتيني، بحيث لا يفي بالمواصفات إلا حوالي 40% من زيت الزيتون المباع على أنه "بكر ممتاز" في إيطاليا.[83] في بعض الحالات، وُضعت ملصقات على زيت الشلجم (المستخرج من الشلجم) مع إضافة لون ونكهة، وبيعت على أنها زيت زيتون.[84]

دفع هذا الاحتيال الواسع النطاق الحكومة الإيطالية إلى إصدار قانون جديد للوسم في عام 2007 للشركات التي تبيع زيت الزيتون، والذي بموجبه يتعين على كل زجاجة من زيت الزيتون الإيطالي أن تُعلن عن المزرعة والمعصرة التي أُنتجت فيها، بالإضافة إلى عرض تفاصيل دقيقة عن الزيوت المستخدمة، بالنسبة للزيوت المخلوطة.[85] مع ذلك، في فبراير 2008، اعترض مسؤولو الاتحاد الأوروبي على القانون الجديد، مشيرين إلى أنه بموجب قواعد الاتحاد الأوروبي، يجب أن يكون هذا الوسم طوعيًا وليس إلزاميًا.[84] بموجب قواعد الاتحاد الأوروبي، يجوز بيع زيت الزيتون على أنه إيطالي حتى لو احتوى على كمية صغيرة فقط من الزيت الإيطالي.[85]

يخضع زيت الزيتون البكر الممتاز لمتطلبات صارمة، ويُفحص بحثًا عن أي "عيوب حسية" تشمل: الزنخ، والرائحة العفنة، والرائحة الخلّية، والرواسب الموحلة. قد تحدث هذه العيوب لأسباب مختلفة. أكثرها شيوعًا هي:

- المواد الخام (الزيتون) المصابة أو المتضررة

- الحصاد غير الكافي، مع وجود اتصال بين الزيتون والتربة[86]

في مارس 2008، نفّذ 400 ضابط شرطة إيطالي عملية "الزيت الذهبي"، واعتقلوا 23 شخصًا وصادروا 85 مزرعة بعد أن كشف تحقيق عن مخطط واسع النطاق لإعادة تسمية زيوت دول البحر الأبيض المتوسط الأخرى على أنها إيطالية.[87]

وفي أبريل 2008، صادرت عملية أخرى سبعة مصانع زيت زيتون وألقت القبض على 40 شخصًا في تسع مقاطعات بشمال وجنوب إيطاليا، بتهمة إضافة الكلوروفيل إلى زيت دوار الشمس وفول الصويا وبيعه على أنه زيت زيتون بكر ممتاز، سواءً في إيطاليا أو في الخارج. وتمت مصادرة 25 ألف لتر من الزيت المغشوش ومنع تصديره.[88]

في 15 مارس 2011، وجّه مكتب المدعي العام في فلورنسا بإيطاليا، بالتعاون مع إدارة الغابات، لائحة اتهام إلى مديرين وموظف في شركة كارابيللي، إحدى العلامات التجارية لشركة جروبو إس أو إس الإسبانية (التي غيّرت اسمها مؤخرًا إلى ديوليو). وتضمنت التهم تزوير وثائق والغش في المواد الغذائية. وصرح محامي كارابيللي، نيري بينوتشي، بأن الشركة لا تشعر بالقلق إزاء هذه التهم، وأن "القضية مبنية على مخالفات في الوثائق"."[89]

في فبراير 2012، حققت السلطات الإسبانية في عملية احتيال دولية في زيت الزيتون، حيث تم تداول زيوت النخيل والأفوكادو ودوار الشمس وزيوت أخرى أرخص على أنها زيت زيتون إيطالي. وذكرت الشرطة أن الزيوت خُلطت في مصنع للديزل الحيوي الصناعي، وغُشّ بعضها لإخفاء علامات كانت ستكشف عن طبيعتها الحقيقية. ولم تكن الزيوت سامة ولا تُشكّل أي خطر على الصحة، وفقًا لبيان صادر عن الحرس المدني. وأُلقي القبض على تسعة عشر شخصًا بعد تحقيق مشترك استمر عامًا كاملًا بين الشرطة وسلطات الضرائب الإسبانية، في إطار عملية لوسيرنا.[90]

يستغل مصنعو زيت الزيتون المغشوش والمختلط استخدام طباعة صغيرة جدًا لبيان أصل الزيت المخلوط كذريعة قانونية.[91]

Journalist Tom Mueller has investigated crime and adulteration in the olive oil business, publishing the article "Slippery Business" in New Yorker magazine,[83] followed by the 2011 book Extra Virginity. On 3 January 2016 Bill Whitaker presented a program on CBS News including interviews with Mueller and with Italian authorities.[92][93] It was reported that in the previous month, 5,000 tons of adulterated olive oil had been sold in Italy, and that organised crime was heavily involved—the term "Agrimafia" was used. The point was made by Mueller that the profit margin on adulterated olive oil was three times that on the illegal narcotic drug cocaine. He said that over 50% of olive oil sold in Italy was adulterated, as was 75–80% of that sold in the US. Whitaker reported that three samples of "extra virgin olive oil" had been bought in a US supermarket and tested; two of the three samples did not meet the required standard, and one of them—from a top-selling US brand—was exceptionally poor.

In early February 2017, the Carabinieri police arrested 33 suspects in the Calabrian mafia's Piromalli 'ndrina ('Ndrangheta), which was allegedly exporting fake extra virgin olive oil to the U.S.; the product was actually inexpensive olive pomace oil fraudulently labeled.[94] Less than a year earlier, the American television program 60 Minutes had warned that "the olive oil business has been corrupted by the Mafia" and that "Agromafia" was a 16 billion dollar per year enterprise. A Carabinieri investigator interviewed on the program said that "olive oil fraud has gone on for the better part of four millennia" but today, it's particularly "easy for the bad guys to either introduce adulterated olive oils or mix in lower quality olive oils with extra-virgin olive oil".[95] Weeks later, a report by Forbes magazine stated that "it's reliably reported that 80% of the Italian olive oil on the [US] market is fraudulent" and that "a massive olive oil scandal is being uncovered in Southern Italy (Puglia, Umbria and Campania)".[96]

مراقبة الجودة والاحتيال

في يوليو 2024، أبلغ الاتحاد الأوروبي عن زيادة ملحوظة في حالات الغش والتزييف في ملصقات زيت الزيتون. وكشف التقرير السنوي للمفوضية الأوروبية حول الغش الغذائي أن زيت الزيتون لا يزال من أكثر المنتجات الغذائية غشًا، حيث وصلت هذه الحوادث إلى مستوى قياسي.[97]

التزييف والغش

تشمل أكثر أشكال الاحتيال في زيت الزيتون شيوعًا ما يلي:

- وضع ملصقات خاطئة على زيوت منخفضة الجودة على أنها زيت زيتون بكر ممتاز

- تخفيف زيت الزيتون بزيوت نباتية أرخص

- الادعاء زورًا بأن زيوتًا من خارج الاتحاد الأوروبي مصدرها الاتحاد الأوروبي

لا تقتصر هذه الممارسات الاحتيالية على خداع المستهلكين فحسب، بل تُقوّض أيضًا سمعة المنتجين الشرعيين، وخاصةً أولئك القادمين من مناطق زراعة الزيتون التقليدية في البحر الأبيض المتوسط.[97]

رد الاتحاد الأوروبي

لمكافحة حالات الاحتيال المتزايدة، اتخذ الاتحاد الأوروبي عدة تدابير:

- زيادة عمليات التفتيش والاختبار لشحنات زيت الزيتون

- تعزيز متطلبات التتبع للمنتجين والموزعين

- تشديد العقوبات على الشركات التي تُدان بالاحتيال

- تحسين التعاون بين سلطات سلامة الأغذية في الدول الأعضاء

كما أطلق الاتحاد الأوروبي حملة توعية عامة لتثقيف المستهلكين حول جودة زيت الزيتون وكيفية تحديد المنتجات الأصلية. [97]

التأثير على الصناعة

أدى تزايد حالات الاحتيال إلى:

- ارتفاع تكاليف الإنتاج للمنتجين النزيهين نتيجةً لزيادة متطلبات الامتثال.

- احتمال خسارة حصة سوقية لزيت الزيتون البكر الممتاز الأصلي، مع غمر السوق بمنتجات مغشوشة وأرخص ثمنًا.

- تزايد تشكك المستهلكين في ادعاءات جودة زيت الزيتون.

يؤكد خبراء الصناعة على أهمية دعم المنتجين ذوي السمعة الطيبة، ويحثون المستهلكين على توخي المزيد من الحذر عند شراء زيت الزيتون، خاصةً عندما تبدو الأسعار منخفضةً بشكل غير معتاد مقارنةً بالجودة المزعومة. [97]

المكونات

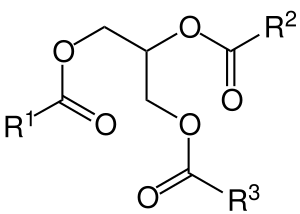

Olive oil is composed mainly of the mixed triglyceride esters of oleic acid, linoleic acid, palmitic acid and of other fatty acids,[98][99] along with traces of squalene (up to 0.7%) and sterols (about 0.2% phytosterol and tocosterols). The composition varies by cultivar, region, altitude, time of harvest, and extraction process.

| Fatty acid | Type | Percentage (m/m methyl esters) | ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oleic acid | Monounsaturated | 55 to 83% | [98] |

| Linoleic acid | Polyunsaturated (omega-6) | 3.5 to 21% | [98][99] |

| Palmitic acid | Saturated | 7.5 to 20% | [98] |

| Stearic acid | Saturated | 0.5 to 5% | [98] |

| α-Linolenic acid | Polyunsaturated (omega-3) | 0 to 1.5% | [98] |

مقارنة بالزيوت النباتية الأخرى

التركيب الفينولي

Olive oil contains traces of phenolics (about 0.5%), such as esters of tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, oleocanthal and oleuropein,[65][100] which give extra virgin olive oil its bitter, pungent taste, and are also implicated in its aroma.[101] Olive oil is a source of at least 30 phenolic compounds, among which are elenolic acid, a marker for maturation of olives,[65][102] and alpha-tocopherol, one of the eight members of the Vitamin E family.[103] Oleuropein, together with other closely related compounds such as 10-hydroxyoleuropein, ligstroside and 10-hydroxyligstroside, are tyrosol esters of elenolic acid.

Other phenolic constituents include flavonoids, lignans and pinoresinol.[104][105]

القيمة الغذائية

| القيمة الغذائية لكل 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| الطاقة | 3،700 kJ (880 kcal) |

0 g | |

100 g | |

| مشبع | 13.8 g |

| أحادي عدم التشبع | 73 g |

| متعدد عدم التشبع | 10.5 g 0.8 g 9.8 g |

0 g | |

| الڤيتامينات | |

| ڤيتامين E | (96%) 14.4 mg |

| ڤيتامين ك | (57%) 60.2 μg |

| مكونات أخرى | |

| ماء | 0 g |

| |

| Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Olive oil is 100% fat, containing no carbohydrates, dietary fiber, protein or water (table).

In a reference amount of 100 غرام (3.5 oz), olive oil supplies 884 kcals of food energy, and is a rich source (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of vitamin E (96% DV) and vitamin K (57% DV) (table).

One tablespoon (13.5 g) of olive oil supplies 500 kJ (119 kcal) of food energy and contains 13.5 g of fat, including 9.9 g of monounsaturated fat (mainly as oleic acid), 1.4 g of polyunsaturated fat (mainly as linoleic acid), and 1.9 g of saturated fat (mainly as palmitic acid).[106]

الآثار الصحية المحتملة

In the United States, the FDA allows producers of olive oil to place the following qualified health claim on product labels:[107][108]

Limited and not conclusive scientific evidence suggests that eating about 2 tbsp. (23 g) of olive oil daily may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease due to the monounsaturated fat in olive oil. To achieve this possible benefit, olive oil is to replace a similar amount of saturated fat and not increase the overall number of calories consumed in a day.

In a review by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in 2011, health claims on olive oil were approved for protection by its polyphenols against oxidation of blood lipids,[109] and for maintenance of normal blood LDL-cholesterol levels by replacing saturated fats in the diet with oleic acid.[110] (See also: Commission Regulation (EU) 432/2012 of 16 May 2012).[111] Despite its approval, the EFSA has noted that a definitive cause-and-effect relationship has not been adequately established for consumption of olive oil and maintaining normal (fasting) blood concentrations of triglycerides, normal blood HDL-cholesterol concentrations, and normal blood glucose concentrations.[112]

A 2014 meta-analysis concluded that increased consumption of olive oil was associated with reduced risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular events and stroke, while monounsaturated fatty acids of mixed animal and plant origin showed no significant effects.[113] Another meta-analysis in 2018 found high-polyphenol olive oil intake was associated with improved measures of total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, malondialdehyde, and oxidized LDL when compared to low-polyphenol olive oils, although it recommended longer studies, and more investigation of non-Mediterranean populations.[114]

انظر أيضًا

المصادر

- ^ أ ب "Olive oil production in 2022, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity/Year (pick lists)". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2025. Retrieved 9 February 2025.

- ^ Davidson, Alan (1999). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press. s.v. Olives. ISBN 0-19-211579-0.

- ^ "International Olive Council". Archived from the original on October 26, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ^ Scanlon, Thomas F. (2005). "The Dispersion of Pederasty and the Athletic Revolution in sixth-century BC Greece", in Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West, ed. B.C. Verstraete and V. Provençal, Harrington Park Press.

- ^ Kennell, Nigel M. "Most Necessary for the Bodies of Men: Olive Oil and its By-products in the Later Greek Gymnasium" in Mark Joyal (ed.), In Altum: Seventy-Five Years of Classical Studies in Newfoundland, 2001; popis pp. 119–133.

- ^ Himes, Norman E. (1963). The Medical History of Contraception. Gamut Press. pp. 86–87.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Kapellakis, Iosif Emmanouil (2008). "Olive oil history, production and by-product management". Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology. 7 (1): 1–26. Bibcode:2008RESBT...7....1K. doi:10.1007/s11157-007-9120-9. S2CID 84992505.

- ^ Foley, B. P.; Hansson, M. C.; Kourkoumelis, D. P.; & Theodoulou, T. A. (2012). "Aspects of ancient Greek trade re-evaluated with amphora DNA evidence". Journal of Archaeological Science, 39(2), 389-398.

- ^ Riley, F. R. "Olive Oil Production on Bronze Age Crete: Nutritional properties, Processing methods, and Storage life of Minoan olive oil". Oxford Journal of Archaeology 21:1:63–75 (2002).

- ^ Hadjisavvas, Sophocles; Chaniotis, Angelos (2012). "Wine and olive oil in Crete and Cyprus: socio-economic aspects". British School at Athens Studies. 20: 157–173. ISSN 2159-4996. JSTOR 23541207.

- ^ Besnarda, Guillaume; André Bervillé, "Multiple origins for Mediterranean olive (Olea europaea L. ssp. europaea) based upon mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms", Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences – Series III – Sciences de la Vie 323:2:173–181 (February 2000); Breton, Catherine; Michel Tersac and André Bervillé, "Genetic diversity and gene flow between the wild olive (oleaster, Olea europaea L.) and the olive: several Plio-Pleistocene refuge zones in the Mediterranean basin suggested by simple sequence repeats analysis", Journal of Biogeography 33:11:1916 (November 2006).

- ^ Schuster, Ruth (17 December 2014). "8,000-year old olive oil found in Galilee, earliest known in world". Haaretz. Archived from the original on February 7, 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ Galili, Ehud; Stanley, Daniel Jean; Sharvit, Jacob; Weinstein-Evron, Mina (December 1997). "Evidence for Earliest Olive-Oil Production in Submerged Settlements off the Carmel Coast, Israel". Journal of Archaeological Science. 24 (12): 1141–1150. Bibcode:1997JArSc..24.1141G. doi:10.1006/jasc.1997.0193.

- ^ Brown, Nathaniel R. (June 11, 2011). "By the Rivers of Babylon: The Near Eastern Background and Influence on the Power Structures Ancient Israel and Judah" (PDF). history.ucsc.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 10, 2014. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ Gardiner, Alan H. (1916). Notes on the Story of Sinuhe. Paris: Librairie Honoré Champion. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2008.

- ^ Riley, F.R. (February 1, 2002). "Olive oil production on bronze age Crete: nutritional properties, processing methods and storage life of Minoan olive oil". Oxford Journal of Archaeology (in الإنجليزية). 21 (1): 63–75. doi:10.1111/1468-0092.00149. ISSN 0262-5253.

- ^ Castleden, Rodney (2005). The Mycenaeans. London and New York: Routledge. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-415-36336-5. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

Huge quantities of olive oil were produced and it must have been a major source of wealth. The simple fact that southern Greece is far more suitable climatically for olive production may explain why the Mycenaean civilization made far greater advances in the south than in the north. The oil had a variety of uses, in cooking, as a dressing, as soap, as lamp oil, and as a base for manufacturing unguents.

- ^ أ ب Shafer-Elliott, Cynthia (2022), Fu, Janling; Shafer-Elliott, Cynthia; Meyers, Carol, eds. (in en), Fruits, Nuts, Vegetables, and Legumes, T&T Clark Handbooks (1 ed.), London: T&T Clark, pp. 144, ISBN 978-0-567-67982-6, https://www.bloomsburyfoodlibrary.com/encyclopedia-chapter?docid=b-9780567679826&tocid=b-9780567679826-chapter8, retrieved on 2025-07-27

- ^ Blázquez, J. M. (October 1992). "The Latest Work on the Export of Baetican Olive Oil to Rome and the Army". Greece and Rome. 39 (2): 173–188. doi:10.1017/S0017383500024153.

- ^ أ ب Nicole Sturzenberger (2007). "Olive Processing Waste Management: Summary" (PDF). oliveoil.ucdavis.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2014. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ Essid, Mohamed Yassine (2012). "Chapter 2. History of Mediterranean Food". MediTerra: The Mediterranean Diet for Sustainable Regional Development. Presses de Sciences Po. pp. 51–69. ISBN 978-2724612486. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ "Olive oil: Refined olive oils". www.accc.gov.au. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةsgray - ^ Peri, Claudio, ed. (2014). The extra virgin olive oil handbook. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. p. 356. ISBN 9781118460436. OCLC 861120215.

- ^ Gritzer, Daniel (May 15, 2023). "Cooking With Olive Oil: Should You Fry and Sear in It or Not?". Serious Eats. Archived from the original on May 18, 2024. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ McManus, Lisa (August 2, 2023). "Olive Oil 101: How to Shop". America's Test Kitchen. Archived from the original on March 30, 2024. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Oaks, Dallin H. "Healing the Sick". ChurchofJesusChrist.org. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Menachot 85b

- ^ Eisenberg, Ronald L. Dictionary of Jewish Terms: A Guide to the Language of Judaism, ISBN 1589797299, 2011, p. 299.

- ^ "Soap Making from Scratch Workshop". Archived from the original on November 20, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ "The olive essence". Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ "Castile Olive Oil Soap, Spain, 2000 BCE". smith.edu. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ "Synthesis of Soap from Olive Oil" (PDF). webpages.uidaho.edu. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ "California olive oil is worth the splurge". ucanr.edu (Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources). Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ Sapra, Sameer; Rogach, Andrey L.; Feldmann, Jochen (2006). "Phosphine-free synthesis of monodisperse CdSe nanocrystals in olive oil". Journal of Materials Chemistry. 16 (33): 3391. doi:10.1039/B607022A.

- ^ "What's the Difference Between Extra Virgin & Regular Olive Oil?". OliveOil.com (in الإنجليزية). 2021-05-04. Archived from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- ^ Peri, Claudio, ed. (2014). The extra-virgin olive oil handbook. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 155–156. ISBN 9781118460450. OCLC 908158600.

- ^ Danby, H., ed. (1933). "Menahoth". The Mishnah. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 8:4 (p. 502). ISBN 0-19-815402-X.

- ^ أ ب Amar, Z. (2015). Flora and Fauna in Maimonides' Teachings (in العبرية). Kfar Darom. p. 73. OCLC 783455868.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ أ ب ت Geoponika – Agricultural Pursuits (in الإنجليزية). Vol. 1. Translated by Owen, T. London: University of Oxford. 1805. pp. 288–289.

- ^ Cf. Danby, H., ed. (1933). "Tohoroth". The Mishnah. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 9:5 (p. 729). ISBN 0-19-815402-X.

- ^ Amar, Z. (2015). Flora and Fauna in Maimonides' Teachings (in العبرية). Kfar Darom. p. 74. OCLC 783455868.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) s.v. Mishnah Tohoroth 9:1 (Maimonides' commentary) - ^ أ ب Frankel, Rafael (1994). "Ancient Oil Mills and Presses in the Land of Israel". In Etan Ayalon (ed.). History and Technology of Olive Oil in the Holy Land (in الإنجليزية). Translated by Jacobson, Jay C. Tel Aviv, Israel: Eretz Israel Museum and Oléarus editions. p. 23. ISBN 0-917526-06-6.

- ^ Mukaddasi (1906) [3rd edition 1967]. de Goeje, M. J. (ed.). Kitāb Aḥsan at-taqāsīm fī maʻrifat al-aqālīm [The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Regions]. Leiden: Brill. p. 181. OCLC 313566614.قالب:Clarify inline

- ^ Amar, Z.; Serri, Yaron (2004). The Land of Israel and Syria as Described by al-Tamimi – Jerusalem Physician of the 10th Century (in العبرية). Ramat-Gan. p. 78. ISBN 965-226-252-8. OCLC 607157392.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Cf. Babylonian Talmud, Menahot 86a, where it says that the olives used to produce this kind of oil had not reached one-third of their natural stage of ripeness, and that it was used principally as a depilatory and to flavor meat. - ^ أ ب ت ث Berbel, Julio; Posadillo, Alejandro (17 January 2018). "Review and Analysis of Alternatives for the Valorisation of Agro-Industrial Olive Oil By-Products". Sustainability. 10 (1): 237. Bibcode:2018Sust...10..237B. doi:10.3390/su10010237. hdl:10396/17426. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ أ ب مؤتمر الأمم المتحدة للتجارة والتنمية Site

- ^ "احصائيات زيت زيتون كاليفورنيا والعالم"" PDF at UC Davis.

- ^ أ ب Vivante, Lucy (2 November 2011). "Gruppo Pieralisi Powers World's Largest Olive Oil Mill in Jaén". Olive Oil Times. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ "Tuscan Extra Virgin Olive Oil: A Product of Excellence". www.discovertuscany.com (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on July 30, 2018. Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- ^ "Associazione Nazionale Città dell'Olio – Citta dell'olio". Archived from the original on July 30, 2018. Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- ^ "La marca Italia se queda con el aceite español. Noticias de Economía". El Confidencial (in الإسبانية). Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved 2017-10-19.

- ^ أ ب ت "Olive Oil Consumption". North American Olive Oil Association. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ "Ministry of Agriculture in Olive Oil sector analysis: The Israeli farmer produces more olive oil and the Israeli public consumes more and pays less money for it". GOV.IL (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved 2022-05-08.

- ^ "Olive Oil Times". Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "New U.S. Olive Oil Standards in Effect Today". Olive Oil Times. October 25, 2010. Archived from the original on February 6, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ Durant, John (September 5, 2000). "U.S. Customs Department, Director Commercial Rulings Division – Country of origin marking of imported olive oil; 19 CFR 134.46; "imported by" language". Archived from the original on January 16, 2009. Retrieved October 15, 2008.

- ^ "Reference to HQ 560944 ruling of the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) on April 27, 1999 blending of Spanish olive oil with Italian olive oil in Italy does not result in a substantial transformation of the Spanish product". United States International Trade Commission Rulings. February 28, 2006. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2008.

- ^ أ ب McGee, Dennis. "Deceptive Olive Oil Labels on Major Brands (includes photos)". Archived from the original on February 6, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ^ Francis, Raymond (1998). "The Olive Oil Scandal" (PDF). beyondhealth.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 27, 2010. Retrieved June 7, 2010.

- ^ Grossi, Marco; Lecce, Giuseppe Di; Toschi, Tullia Gallina; Ricco, Bruno (September 2014). "Fast and Accurate Determination of Olive Oil Acidity by Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy" (PDF). IEEE Sensors Journal. 14 (9): 2947–2954. Bibcode:2014ISenJ..14.2947G. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2014.2321323.

- ^ Wallace, H. M.; Walton, D. A. (2011-01-01), Yahia, Elhadi M., ed., Macadamia (Macadamia integrifolia, Macadamia tetraphylla and hybrids), Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition, Woodhead Publishing, pp. 450–474e, doi:, ISBN 978-1-84569-735-8, https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B978184569735850019X, retrieved on 2025-02-13

- ^ Riaz, Mian N.; Rokey, Galen J. (2012-01-01), Riaz, Mian N.; Rokey, Galen J., eds., Impact of particle size and other ingredients on extruded foods and feeds, Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition, Woodhead Publishing, pp. 55–63, doi:, ISBN 978-1-84569-664-1, https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9781845696641500062, retrieved on 2025-02-13

- ^ Grossi, Marco; Di Lecce, Giuseppe; Arru, Marco; Gallina Toschi, Tullia; Riccò, Bruno (February 2015). "An opto-electronic system for in-situ determination of peroxide value and total phenol content in olive oil" (PDF). Journal of Food Engineering. 146: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2014.08.015.

- ^ أ ب ت Bendini, Alessandra; Cerretani, Lorenzo; Carrasco-Pancorbo, Alegria; Gómez-Caravaca, Ana Maria; Segura-Carretero, Antonio; Fernández-Gutiérrez, Alberto; Lercker, Giovanni (6 August 2007). "Phenolic Molecules in Virgin Olive Oils: a Survey of Their Sensory Properties, Health Effects, Antioxidant Activity and Analytical Methods. An Overview of the Last Decade Alessandra". Molecules. 12 (8): 1679–1719. doi:10.3390/12081679. PMC 6149152. PMID 17960082.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "The 101 of olive oil designations and definitions". Australian Olive Association. Archived from the original on February 26, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "Designations and definitions of olive oils". International Olive Council. Archived from the original on December 3, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ^ "What is extra virgin olive oil?". Olive Oil Times. 2018. Archived from the original on February 9, 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Olive Oil Production". Prosodol. Archived from the original on November 19, 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ "United States Standard for Grades of Olive Oil". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on November 11, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ أ ب "United States Standard for Grades of Olive Oil" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 16, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ "Olive Oil Standards in the US: An Overview". oliveoil.com. 18 May 2021. Archived from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ NAOOA. "NAOOA Certified Quality Seal Program". www.aboutoliveoil.org (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on January 3, 2020. Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- ^ "Certification Process". California Olive Oil Council (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on January 3, 2020. Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- ^ "What Makes Olive Oil Extra Virgin and Can I Trust the Label?". FoodPrint (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2019-12-16. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020. Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- ^ "Bone density scan ... Olive oil ... Bursitis". Women's Health Advisor. 14 (7): 8. 2010.قالب:MEDRS

- ^ Bogle, Deborah; Mueller, Tom (12 May 2012). "Losing our Virginity". The Advertiser. pp. 11–14.

- ^ Williams, Daniel (9 September 2010). "Olive pomace oil: not what you might think". Olive Oil Times. Archived from the original on April 23, 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ "California Olive Ranch". Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ Προϊόντα Προστατευόμενης Ονομασίας Προέλευσης και Προστατευόμενης Γεωγραφικής Ένδειξης [Protected Designation of Origin and Protected Geographical Indication] (in اليونانية). Archived from the original on يوليو 21, 2011. Retrieved مايو 9, 2011.

- ^ Drummond, Linda. Sunday Telegraph (Australia), October 17, 2010 Sunday, Features; p. 10.

- ^ "Report Scusi, Lei E' Vergine?". rai.it. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ^ أ ب Mueller, Tom (August 13, 2007). "Slippery Business". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ أ ب "EUbusiness.com". Archived from the original on مارس 9, 2008.

- ^ أ ب Moore, Malcolm (May 7, 2007). "Murky Italian olive oil to be pored over". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ "草刈りは定期的に". Novaoliva.com. February 21, 2013. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Moore, Malcolm (5 March 2008). "Italian police crack down on olive oil fraud". The Telegraph.

- ^ Pisa, Nick (April 22, 2008). "Forty arrested in new 'fake' olive oil scam". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Archived from the original on January 9, 2009. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ "Investigations Into Deodorized Olive Oils". Olive Oil Times. March 29, 2011. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "Spanish Police Say Palm, Avocado, Sunflower Was Passed Off as Olive Oil". Olive Oil Times. February 14, 2012. Archived from the original on February 6, 2017. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- ^ Nadeau, Barbie Latza (2015-11-14). "Has the Italian Mafia Sold You Fake Extra Virgin Olive Oil?". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on November 18, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ Whitaker, Bill (3 January 2016). "Agromafia". CBS News.

- ^ "Mafia Control of Olive Oil the Topic of '60 Minutes' Report". Olive Oil Times. 3 January 2016. Archived from the original on November 9, 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2016.. Summary of CBS video

- ^ "Italy Arrests 33 Accused of Olive Oil Fraud 16 February 2017". February 16, 2017. Archived from the original on September 20, 2018. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ "Don't fall victim to olive oil fraud 3 January 2016". CBS News. January 3, 2016. Archived from the original on September 20, 2018. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ "The Olive Oil Scam: If 80% Is Fake, Why Do You Keep Buying It? 10 February 2016". Forbes. Archived from the original on September 20, 2018. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Goodier, Michael (2024-07-29). "Olive oil fraud and mislabelling cases hit record high in EU". The Guardian (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-12-12.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Boskou, Dimitrios; Blekas, Georgios; Tsimidou, Maria (April 2006). "4 Olive Oil Composition". Olive Oil. Taylor & Francis. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-893997-88-2. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ أ ب Beltrán, Gabriel; del Rio, Carmen; Sánchez, Sebastián; Martínez, Leopoldo (June 2004). "Influence of Harvest Date and Crop Yield on the Fatty Acid Composition of Virgin Olive Oils from Cv. Picual". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 52 (11): 3434–3440. Bibcode:2004JAFC...52.3434B. doi:10.1021/jf049894n. PMID 15161211.

- ^ Tripoli, Elisa; Giammanco, Marco; Tabacchi, Garden; Di Majo, Danila; Giammanco, Santo; La Guardia, Maurizio (2005). "The phenolic compounds of olive oil: structure, biological activity and beneficial effects on human health". Nutrition Research Reviews. 18 (1): 98–112. doi:10.1079/NRR200495. PMID 19079898. S2CID 221216561.

- ^ Genovese, Alessandro; Caporaso, Nicola; Villani, Veronica; Paduano, Antonello; Sacchi, Raffaele (August 2015). "Olive oil phenolic compounds affect the release of aroma compounds". Food Chemistry. 181: 284–294. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.02.097. PMID 25794752.

- ^ Lozano-Sánchez, Jesús; Castro-Puyana, María; Mendiola, Jose; Segura-Carretero, Antonio; Cifuentes, Alejandro; Ibáez, Elena (15 September 2014). "Recovering Bioactive Compounds from Olive Oil Filter Cake by Advanced Extraction Techniques". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 15 (9): 16270–16283. doi:10.3390/ijms150916270. PMC 4200768. PMID 25226536.

- ^ Wagner KH, Kamal-Eldin A, Elmadfa I (2004). "Gamma-tocopherol--an underestimated vitamin?". Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism. 48 (3): 169–88. doi:10.1159/000079555. PMID 15256801. S2CID 24827255.

In North America, the intake of γ-tocopherol has been estimated to exceed that of α-tocopherol by a factor of 2–4 ... due to the fact that soybean oil is the predominant vegetable oil in the American diet (76.4%) followed by corn oil and canola oil (both 7%) ... The supply of dietary fats ... is much more diverse in Europe ... The oils mainly consumed in Europe, i.e. sunflower, olive and canola oil, provide less γ-tocopherol but more α-tocopherol ... [T]he ratio of α-:γ-tocopherol is at least 1:2. Therefore, the average γ-tocopherol intake can be estimated as 4–6 mg/day, which is about 25–35% of the USA intake. In accordance with the lower estimated European intake of γ-tocopherol, the serum levels of γ-tocopherol in European populations are 4–20 times lower than that of α-tocopherol

- ^ Owen, R.W; Giacosa, A; Hull, W.E; Haubner, R; Spiegelhalder, B; Bartsch, H (June 2000). "The antioxidant/anticancer potential of phenolic compounds isolated from olive oil". European Journal of Cancer. 36 (10): 1235–1247. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00103-9. PMID 10882862.

- ^ Owen, Robert W; Mier, Walter; Giacosa, Attilio; Hull, William E; Spiegelhalder, Bertold; Bartsch, Helmut (July 2000). "Identification of Lignans as Major Components in the Phenolic Fraction of Olive Oil". Clinical Chemistry. 46 (7): 976–988. doi:10.1093/clinchem/46.7.976. PMID 10894841.

- ^ "Nutrient composition for a tablespoon of olive oil; 13.5 g from the pick list for portion". USDA FoodData Central. 1 April 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ "FDA Allows Qualified Health Claim to Decrease Risk of Coronary Heart Disease". US Food and Drug Administration. November 2004. Archived from the original on March 10, 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ Brackett, R. E. (November 2004). "Letter Responding to Health Claim Petition dated August 28, 2003: Monounsaturated Fatty Acids from Olive Oil and Coronary Heart Disease (Docket No 2003Q-0559)". US Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ^ European Food Safety Authority (2011). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to polyphenols in olive". EFSA Journal. 9 (4): 2033. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2033.

- ^ European Food Safety Authority (2011). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to oleic acid intended to replace saturated fatty acids (SFAs) in foods or diets". EFSA Journal. 9 (4): 2043. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2043.

- ^ "Commission Regulation (EU) No 432/2012 of 16 May 2012 establishing a list of permitted health claims made on foods, other than those referring to the reduction of disease risk and to children's development and health. Text with EEA relevance". Official Journal of the European Union. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

- ^ Scientific Committee/Scientific Panel of the European Food Safety Authority (2011). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to olive oil and maintenance of normal blood LDL-cholesterol concentrations (ID 1316, 1332), maintenance of normal (fasting) blood concentrations of triglycerides (ID 1316, 1332), maintenance of normal blood HDL cholesterol concentrations (ID 1316, 1332) and maintenance of normal blood glucose concentrations (ID 4244) under Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006". EFSA Journal. 9 (4): 2044 [19 pp]. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2044. hdl:2434/174506.

- ^ Schwingshackl, L; Hoffmann, G. (2014). "Monounsaturated fatty acids, olive oil and health status: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies". Lipids in Health and Disease. 13 (1): 154. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-13-154. PMC 4198773. PMID 25274026.

- ^ George, Elena S.; Marshall, Skye; Mayr, Hannah L; Trakman, Gina L.; Tatucu-Babet, Oana A.; Lassemillante, Annie-Claude M.; Bramley, Andrea; Reddy, Anjana J.; Forsyth, Adrienne; Tierney, Audrey C.; Thomas, Colleen J.; Itsiopoulos, Catherine; Marx, Wolfgang (25 September 2019). "The effect of high-polyphenol extra virgin olive oil on cardiovascular risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 59 (17): 2772–2795. doi:10.1080/10408398.2018.1470491. PMID 29708409.

قراءات إضافية

- Caruso, Tiziano; Magnano di San Lio, Eugenio (eds.). La Sicilia dell'olio, Giuseppe Maimone Editore, Catania, 2008, ISBN 978-88-7751-281-9

- Mueller, Tom. Extra Virginity – The Sublime and Scandalous World of Olive Oil, Atlantic Books, London, 2012. ISBN 978-1-84887-004-8.

- Pagnol, Jean. L'Olivier, Aubanel, 1975. ISBN 2-7006-0064-9.

- Palumbo, Mary; Linda J. Harris (December 2011) "Microbiological Food Safety of Olive Oil: A Review of the Literature" (PDF), University of California, Davis

- Preedy, V. R.; Watson, R. R. (eds.). Olives and Olive Oil in Health and Disease Prevention, Academic Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-12-374420-3.

- Rosenblum, Mort. Olives: The Life and Lore of a Noble Fruit, North Point Press, 1996. ISBN 0-86547-503-2.

- CODEX STAN 33-1981 Standard for Olive Oils and Olive Pomace Oils

- الموسوعة الحديثة للعلاج بالأعشاب والطب البديل . أحمد محمد عوف

- [http://rania.madarat.info/archives/28 مدارات

- RT,Moreton."Hand book of pharmaceutical excipients

(6th) Edition."(470-473)

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- CS1 العبرية-language sources (he)

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 uses اليونانية-language script (el)

- CS1 اليونانية-language sources (el)

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2020

- Articles needing additional references from June 2016

- All articles needing additional references

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles containing explicitly cited عربية-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Articles containing إيطالية-language text

- Pages with empty portal template

- مأكولات

- زيوت

- توابل

- زيت زيتون

- زيوت الطبخ

- زيوت نباتية

- مثبطات أوكسيديز أحادي الأمين

- مطبخ متوسطي

- Olive oil

- Condiments

- Cooking oils

- Mediterranean cuisine

- Vegetable oils

- Cuisine of California