غراميات الممالك الثلاث

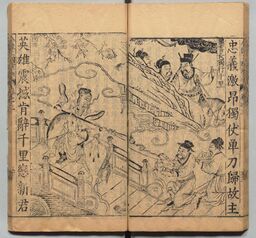

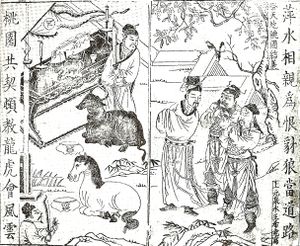

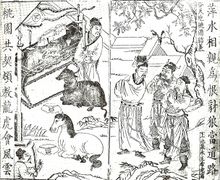

رسم من أسرة مينگ العدد المطبوع لرواية عام 1591، مجموعة جامعة پكينگ. | |

| المؤلف | لوو گوانژونگ |

|---|---|

| العنوان الأصلي | 三國演義 |

| البلد | الصين |

| اللغة | الصينية |

| الموضوع | الصين القديمة |

| الصنف | تاريخ، حرب |

تاريخ النشر | القرن 14 |

| نوع الوسائط | |

| ISBN | 978-7-119-00590-4 |

| تب. مك.كونگ | PL2690.S3 E53 1995 |

| غراميات الممالك الثلاث | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

غراميات الممالك الثلاث مكتوبة بحروف صينية تقليدية (أعلى) ومبسطة (أسفل) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الصينية التقليدية | 三國演義 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الحروف المبسطة | 三国演义 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | Tam quốc diễn nghĩa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 三國演義 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 삼국지연의 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 三國志演義 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 三国志演義 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | さんごくしえんぎ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

غراميات الممالك الثلاث (إنگليزية: Romance of the Three Kingdoms ؛ الصينية التقليدية: 三國演義; الصينية المبسطة: 三国演义; پنين: Sānguó Yǎnyì)، تُنسب إلى لوو گوانژونگ، هي رواية تاريخية تدور أحداثها في سنوات الاضطراب المؤدية إلى نهاية أسرة هان وفترة الممالك الثلاث في التاريخ الصيني، بدءاً من عام 169 ونهايةً بإعادة توحيد الصين في 280.

القصة التاريخية، الأسطورية والخرافية، تصور في إطار رومانسي ودرامي حياة الإقطاعيين وخدمهم، الذين حاولوا استبدال أسرة هان المتضائلة أو استعادتها. بينما تتبع الرواية مئات الشخصيات، فهي تركز بشكل أساسي على كتل السلطة الثلاثة التي نشأت من بقايا أسرة هان، والتي ستشكل في النهاية الدويلات الثالثة في كان ويي، شو هان، ووو الغربية. تتعامل الرواية مع المؤمرات، المعارك الشخصية والعسكرية، المؤامرات، ونضال هذه الدويلات لتحقيق الهيمنة لما يقرب من 100 سنة.

غراميات الممالك الثلاث من المشهود لها باعتبارها واحدة من الروايات الكلاسيكية العظيمة الأربعة في الأدب الصيني؛ وتضم 800.000 كلمة وما يقارب من ألف شخصية درامية (معظمها تاريخية) في 120 فصل.[1] الرواية من بين أكثر الروايات الأدبية المحبوبة في شرق آسيا،[2] وتأثيرها الأدبي في المنطقة يقارن بتأثير أعمال شيكسپير في الأدب الإنگليزي.[3] فإنه يمكن القول إن الرواية التاريخية الأكثر قراءة على نطاق واسع في أواخر الصين الإمبراطورية والحديثة.[4]

الأصول والنسخ

قبل المصنفات المكتوبة وُجدت أساطير من فترة الممالك الثلاثة كتراث شفهي.[citation needed] بتركيزها على تاريخ صينيي الهان، القصص الشعبية التي نمت في عهد أباطرة المنغول من أسرة يوان. في عهد أسرة مينگ اللاحقة كان هناك اهتمام بالمسرحيات والروايات مما أسفر عن المزيد من التوسعات وإعادة رواية القصص.

كانت هناك محاولة مبكرة لجمع هذه القصص في عمل مكتوب، پينگهوا، سانگوژي پينگهوا (الصينية المبسطة: 三国志评话; الصينية التقليدية: 三國志平話; پنين: Sānguózhì Pínghuà; lit. 'قصة سجلات الممالك الثلاث')، نشرت ما بين 1321 و1323. جمع هذا الإصدار موضوعات أسطورية، سحرية وأخلاقية لجذب طبقة الفلاحين. نسجت عناصر التناسخ والكارما في هذه النسخة من القصة.

توسيع التاريخ

غراميات الممالك الثلاث تـُنسَب تقليدياً إلى لوو گوانژونگ،[5] الكاتب المسرحي الذي عاش في وقت بين 1315 و 1400 (أواخر أسرة يوان إلى مطلع أسرة مينگ) الذي عـُرِف بجمع المسرحيات التاريخية بالأساليب التي كانت سائدة في فترة يوان.[6] وقد طـُبـِعت لأول مرة في 1522[6] بعنوان Sanguozhi Tongsu Yanyi (三國志通俗演義/三国志通俗演义) في طبعة حملت تاريخاً للمقدمة 1494، ولعله زائف. قد يكون النص قد تم تعميمه قبل أيٍ من التاريخين في المخطوطات المكتوبة بخط اليد.[7]

على أي حال، سواء كان تاريخًا سابقًا أو لاحقًا للتأليف، سواء كان لوو گوانژونگ مسؤولاً أم لا، استخدم المؤلف السجلات التاريخية المتاحة، بما في ذلك "سجلات الممالك الثلاث" التي جمعها تشن شو، التي غطت الأحداث من تمرد العمامات الصفراء في 184 إلى توحيد الممالك الثلاث تحت أسرة جين في 280. تتضمن الرواية أيضًا مواد من الأعمال الشعرية لأسرة تانگ وأوپرات أسرة يوان وتفسيره الشخصي لعناصر مثل الفضيلة والشرعية. جمع المؤلف هذه المعرفة التاريخية بموهبة لرواية القصص فخلق نسيجاً غنياً من الشخصيات.[8]

المراجعات والنصوص الموحدة

Luo Guanzhong's version in 24 volumes, known as the Sanguozhi Tongsu Yanyi, is now held in the Shanghai Library in China, Tenri Central Library in Japan, and several other major libraries. Various 10-volume, 12-volume and 20-volume recensions of Luo's text, made between 1522 and 1690, are also held at libraries around the world. However, the standard text familiar to general readers is a recension by Mao Lun and his son Mao Zonggang.

At the end of the Ming dynasty, "Li Zhuowu" added commentary to the Luo version, which expanded its circulation and influence.[9] While Li Zhuowu, was the art name of Li Zhi, the commentary was likely written by an imposter (Ye Zhou).[10] Nevertheless, it is consistent with the anti-authoritarian views of the historical Li Shi. The persona of Li Zhuowu "is presented as a reader who appreciates the text, an interpreter and appropriate model for readers unfamiliar with the form".[10]

In addition to "quandian" (placement of small circles and dots to the right of the text to indicate emphasis), Li Zhuowu included interlineal comments and comments at the end of chapters. The interlineal comments, written with smaller characters alongside the novel text, were typically short exclamations.[10] For example, when Liu Bei is described in the novel text as not fond of reading, Li exclaims: "Taking no joy in reading is the mark of a hero".[10] The comments at the end of chapters were longer and were often ironic and conversational. For example, There is a comment in one of the later chapters about the relevance of the novel as follows: “Since [similar events] were narrated previously, this does nothing more than change the names to pad out the narrative. How irritating! This is why it is an ‘elaboration’ [yanyi] of the Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms [Sanguo zhi]. Laughable!”. However, another comment emphasizes the need for elaboration: "Even so, this is a 'popular romance' and not official history. If it were not so [embellished], then how could it be 'popular'? ".[10]

This version of the novel contained numerous illustrations of scenes depicted in the text. Illustrations were a near ubiquitous feature of late Ming dynasty books. The flourishing of book illustrations at the time apparently resulted from increased prosperity of the elite which allowed them greater opportunity to read for fun.[11]

A 2-page illustration from Zhou Yue's 1591 edition: "Guan Yu Traveled One Thousand Li Alone". Guan Yu is depicted on his horse Red Hare

الحبكة

من أعظم انجازات غرام الممالك الثلاث التعقيد الشديد لقصصها وشخصياتها. تحتوي الرواية على قصص ثانوية عديدة. الملخص التالي للحبكة الرئيسية ولبعض الخطوط العريضة الشهيرة للقصة.

تمرد العمائم الصفر والحضور العشرة

مقالة مفصلة: تمرد العمائم الصفر

مقالة مفصلة: تمرد العمائم الصفر

In the late second century, towards the end of the Han dynasty in China, corruption was rampant on all levels throughout the government, with treacherous eunuchs and villainous officials deceiving the emperor and persecuting those who stood up to them. The Han Empire gradually deteriorated and became increasingly fragmented, with many regional officials being warlords with their own armies. In the meantime, the common people suffered, and the Yellow Turban Rebellion (led by Zhang Jiao and his brothers) eventually broke out during the reign of Emperor Ling.

The rebellion was barely suppressed by imperial forces commanded by the general He Jin. Shortly after Emperor Ling's death, He Jin installed the young Emperor Shao on the throne and took control of the central government. The Ten Attendants, a group of influential court eunuchs, feared that He Jin was growing too powerful, so they lured him into the palace and assassinated him. In revenge, He Jin's followers broke into the palace and indiscriminately slaughtered any person who looked like a eunuch. In the ensuing chaos, Emperor Shao and his younger half-brother, the Prince of Chenliu, disappeared from the palace.

طغيان دونگ ژوو

The missing emperor and prince were found by soldiers of the warlord Dong Zhuo, who escorted them back to the palace and used the opportunity to seize control of the imperial capital, Luoyang, under the pretext of protecting the emperor. Dong Zhuo later deposed Emperor Shao and replaced him with the Prince of Chenliu (Emperor Xian), who was merely a figurehead under his control. Dong Zhuo monopolised state power, persecuted his political opponents, and oppressed the common people for his personal gain. During this time, there were two attempts on his life: the first was by a military officer Wu Fu (伍孚), who failed and died a gruesome death; the second was by Cao Cao, who was also unsuccessful but managed to escape.

Cao Cao fled from Luoyang, returned to his home commandery, and sent out a fake imperial edict to various warlords, calling them to rise up against Dong Zhuo. Under Yuan Shao's leadership, eighteen warlords formed a coalition and launched a punitive campaign against Dong Zhuo. After Dong Zhuo lost the battles of Sishui Pass and Hulao Pass, he forced the citizens of Luoyang to relocate to Chang'an with him and burnt down Luoyang. The coalition ultimately broke up due to indecisive leadership and conflicting interests among its members. Meanwhile, in Chang'an, Dong Zhuo was betrayed and murdered by his foster son Lü Bu in a dispute over the maiden Diaochan as part of a plot orchestrated by the minister Wang Yun.

النزاع بين مختلف القادة والنبلاء

In the meantime, the Han Empire was already disintegrating into civil war as warlords fought for territories and power. Sun Jian found the Imperial Seal in the ruins of Luoyang and secretly kept it for himself. When Yuan Shao confronted him, he refused to hand over the Imperial Seal and left, but was attacked by Liu Biao (acting on Yuan Shao's instruction) on the way back to his base. At the same time, Yuan Shao waged war against Gongsun Zan to consolidate his power in northern China. Other warlords such as Cao Cao and Liu Bei, who initially had no titles or land, were also gradually forming their own armies and taking control of territories. During those times of upheaval, Cao Cao saved Emperor Xian from Dong Zhuo's followers, established the new imperial capital in Xu, and became the new head of the central government. He also defeated rival warlords such as Lü Bu, Yuan Shu and Zhang Xiu in a series of wars and gained control over much of central China.

Meanwhile, Sun Jian was killed in an ambush by Liu Biao's forces. His eldest son, Sun Ce, delivered the Imperial Seal as a tribute to the warlord Yuan Shu, a rising pretender to the throne, in exchange for troops and horses. Sun Ce then secured himself a power base in the rich riverlands of Jiangdong (Wu), on which the state of Eastern Wu was founded later. Tragically, Sun Ce also died at the pinnacle of his career from illness under stress of his terrifying encounter with the ghost of Yu Ji, a venerable magician whom he had falsely accused of heresy and executed in jealousy. Sun Quan, his younger brother and successor, proved to be a capable and charismatic ruler. With assistance from Zhou Yu, Zhang Zhao and others, Sun Quan found hidden talents such as Lu Su to serve him, built up his military forces, and maintained stability in Jiangdong.

- سون تسى يؤسس أسرة حاكمة في جيانگدونگ

طموح ليو بـِيْ

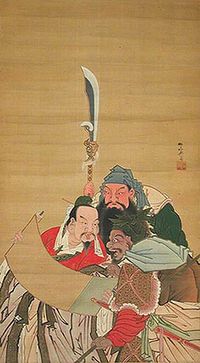

Liu Bei and his oath brothers Guan Yu and Zhang Fei swore allegiance to the Han Empire in the Oath of the Peach Garden and pledged to do their best for the people. However, their ambitions were not realised as they did not receive due recognition for helping to suppress the Yellow Turban Rebellion and participating in the campaign against Dong Zhuo. After Liu Bei succeeded Tao Qian as the governor of Xu Province, he offered shelter to Lü Bu, who had just been defeated by Cao Cao. However, Lü Bu betrayed his host, seized control of the province and attacked Liu Bei. After combining forces with Cao Cao to defeat Lü Bu at the Battle of Xiapi, Liu Bei followed Cao Cao back to the imperial capital, Xu, where Emperor Xian honoured him as his "Imperial Uncle" upon learning that he was also a descendant of the imperial clan. When Cao Cao showed signs that he wanted to usurp the throne, Emperor Xian wrote a secret decree in blood to his father-in-law, Dong Cheng, and ordered him to get rid of Cao Cao. Dong Cheng secretly contacted Liu Bei, Ma Teng and others, and they planned to assassinate Cao Cao. However, their plans were leaked, and Cao Cao had Dong Cheng and the others arrested and executed along with their families.

Liu Bei had already left the imperial capital when the plot was exposed, and he moved on to seize control of Xu Province from Che Zhou, the new governor appointed by Cao Cao. In retaliation, Cao Cao attacked Xu Province and defeated Liu Bei, causing him to be separated from his oath brothers. While Liu Bei briefly joined Yuan Shao after his defeat, Zhang Fei took control of a small city, and Guan Yu temporarily served under Cao Cao and helped him slay two of Yuan Shao's generals in battle. The three oath brothers were eventually reunited and managed to establish a new base in Runan, but they were defeated by Cao Cao's forces again so they retreated south to Jing Province, where they took shelter under the governor Liu Biao.

معركة الجروف الحمر

عُين تساو تساو كمستشار وقاد قواته إلى الجنوب للهجوم على ليو بـِيْ بعد توحيد وسط وشمال الصين. هزم مرتين في شينيه من قبل ليو بـِيْ، لكن ليو كذلك خسر البلاد. قاد ليو بـِيْ أنصاره والمدنيين في خروج إلى الجنوب ووصلوا جيانگشيا.

تحليل أدبي

تعد رواية غراميات الممالك الثلاث أهم أعمال لوو، وهي أول رواية تاريخية طويلة مكتملة في الأدب الصيني، استمد موضوعها من الصراع الذي نشب بين ممالك وو، وي، وشو. تناولت الرواية الأحداث التاريخية في الفترة الممتدة من أواخر عهد مملكة هان الشرقية إلى مطلع عهد مملكة جين، أي ما يقارب المئة عام، والصراع السياسي والعسكري بين الممالك، والتناقضات الاجتماعية، وكشفت اللثام عن النزاع السافر والتناقض الكامن في المجتمع، وفضحت جرائم الطغمة الحاكمة، وصورت معاناة العامة في صراعهم من أجل لقمة العيش، وتغنت بأمجاد الشعب الصيني وحكمته. أفاد الكاتب في كتابة روايته من المراجع التاريخية، ونصوص الأدب الشعبي القديم هوا بن، ونصوص الأوبرا الصينية، والحكايات الشعبية الشفوية القديمة، إضافة إلى خبرة المؤلف وعبقريته التي حولتها من كتاب في التاريخ إلى عمل أدبي معاصر في بنية فنية متينة ومشوقة. ومع أن الرواية تناولت أحداثاً تاريخية وقعت ومضت، إلا أنها حملت مضامين فكرية معاصرة من خلال فضحها دسائس شخصيات الطبقة الحاكمة وخبثها ونفاقها وبشاعتها، وتمجيدها شخصيات تاريخية تحمل قيماً نضالية عبّرت عن معاناة أفراد الشعب ورغبته في حياة مستقرة وآمنة.

إن انتقال الكاتب بين الشمال والجنوب، وقربه من طبقات المجتمع الدنيا، ومعرفته بتفاصيل حياتهم مكنته من رسم شخصيات نابضة بالحياة مثل تساو تساو، تشانگ في، ليو بي، گه ليانگ مما جعل الرواية مقروءة ومفضلة لدى العامة منذ كتابتها حتى اليوم.

تحتل رواية غراميات الممالك الثلاث مكانة رفيعة و لها تأثير عميق في تاريخ الأدب الصيني. وقد ظهرت مئات الأعمال الروائية والأوبرات المستمدة أو المقتبسة منها. وهي تعدّ نموذجاً أدبياً وفنياً، ومرجعاً تعليمياً في الشؤون العسكرية وتكتيك الحروب. وتعود أقدم مخطوطة للرواية إلى عام 1522، وهي مؤلفة من أربع وعشرين لفافة (مجلد) ومئتين وأربعين فصلاً.

تمتاز أعمال گوانژونگ بكثرة الشخصيات، وتعدد الحبكات الثانوية، وعمق تقنية السرد القصصي، ورسم مفصل ودقيق وحيوي للشخصيات، ولغة تجمع بين التقليدية والمعاصرة.

الوقع الثقافي

Besides the famous Peach Garden Oath, many Chinese proverbs in use today are derived from the novel:

| الترجمة | بالصينية | التفسير |

|---|---|---|

| Brothers are like limbs, wives and children are like clothing. Torn clothing can be repaired; how can broken limbs be mended? | الصينية المبسطة: 兄弟如手足,妻子如衣服。衣服破,尚可缝; 手足断,安可续?; الصينية التقليدية: 兄弟如手足,妻子如衣服。衣服破,尚可縫; 手足斷,安可續?[12] |

It means that wives and children, like clothing, are replaceable if lost but the same does not hold true for one's brothers (or friends). |

| Liu Bei "borrows" Jing Province – borrowing without returning. | الصينية المبسطة: 刘备借荆州——有借无还; الصينية التقليدية: 劉備借荆州——有借無還 الصينية المبسطة: 刘备借荆州,一借无回头; الصينية التقليدية: 劉備借荆州,一借無回頭 |

This proverb describes the situation of a person borrowing something without the intention of returning it. |

| Speak of Cao Cao and Cao Cao arrives. | الصينية المبسطة: 说曹操,曹操到; الصينية التقليدية: 說曹操,曹操到 الصينية المبسطة: 说曹操曹操就到; الصينية التقليدية: 說曹操曹操就到 |

Equivalent to speak of the devil. Describes the situation of a person appearing precisely when being spoken about. |

| Three reeking tanners (are enough to) overcome one Zhuge Liang. | الصينية المبسطة: 三个臭皮匠,胜过一个诸葛亮; الصينية التقليدية: 三個臭皮匠,勝過一個諸葛亮 الصينية المبسطة: 三个臭皮匠,赛过一个诸葛亮; الصينية التقليدية: 三個臭皮匠,賽過一個諸葛亮 الصينية المبسطة: 三个臭裨将,顶个诸葛亮; الصينية التقليدية: 三个臭裨将,頂個諸葛亮 |

Three inferior people can overpower a superior person when they combine their strengths. One variation is "subordinate generals" (الصينية المبسطة: 裨将; الصينية التقليدية: 裨將; píjiàng) instead of "tanners" (皮匠; píjiàng). |

| Eastern Wu arranges a false marriage that turns into a real one. | الصينية المبسطة: 东吴招亲——弄假成真; الصينية التقليدية: 東吳招親——弄假成真 | When a plan to falsely offer something backfires with the result that the thing originally offered is appropriated by the intended victim of the hoax. |

| Losing the lady and crippling the army. | الصينية المبسطة: 赔了夫人又折兵; الصينية التقليدية: 賠了夫人又折兵 | The "lady" lost here was actually Sun Quan's sister Lady Sun. Zhou Yu's plan to capture Liu Bei by means of a false marriage proposal failed and Lady Sun really became Liu's wife (see above). Zhou Yu later led his troops in an attempt to attack Liu Bei but fell into an ambush and suffered a crushing defeat. This saying is now used to describe the situations where a person either makes double losses in a deal or loses on both sides of it. |

| Every person on the street knows what is in Sima Zhao's mind. | الصينية المبسطة: 司马昭之心,路人皆知; الصينية التقليدية: 司馬昭之心,路人皆知 | As Sima Zhao gradually rose to power in Wei, his intention to usurp state power became more obvious. The young Wei emperor Cao Mao once lamented to his loyal ministers, "Every person on the street knows what is in Sima Zhao's mind (that he wanted to usurp the throne)." This saying is now used to describe a situation where a person's intention or ambition is rather obvious. |

| The young should not read Water Margin, and the old should not read Three Kingdoms. | الصينية المبسطة: 少不读水浒, 老不读三国; الصينية التقليدية: 少不讀水滸, 老不讀三國 | The former depicts the lives of outlaws and their defiance of the social system and may have a negative influence on adolescent boys, as well as the novel's depiction of gruesome violence. The latter presents every manner of stratagem and fraud and may tempt older readers to engage in such thinking. |

The writing style adopted by Romance of the Three Kingdoms was part of the emergence of written vernacular during the Ming period, as part of the so-called "Four Masterworks" (si da qishu).[13]

نواحي بوذية

سجلت غراميات الممالك الثلاث قصص راهب بوذي يُدعى پوجينگ (普净)، الذي كان صديقاً لـ گوان يو. Pujing made his first appearance during Guan's arduous journey of crossing five passes and slaying six generals, in which he warned Guan of an assassination plot. As the novel was written in the Ming dynasty, more than 1,000 years after the era, these stories showed that Buddhism had long been a significant ingredient of the mainstream culture and may not be historically accurate.[مطلوب توضيح] Luo Guanzhong preserved these descriptions from earlier versions of the novel to support his portrait of Guan as a faithful man of virtue. Guan has since then been respectfully addressed as "Lord Guan" or Guan Gong.

اقتباسات

قصة غراميات الممالك الثلاث سردت في أشكال عديدة منها المسلسلات التلفزيونية، المانگا وألعاب الڤيديو.

انظر أيضاً

- قائمة أشخاص من الممالك الثلاث، قائمة بالشخصيات التاريخية البارزة في فترة الممالك الثلاث (220–280)

- قائمة شخصيات خيالية من الممالك الثلاث، قائمة للشخصيات الخيالية في فترة الممالك الثلاث (220–280)

- قائمة القصص الخيالية في غراميات الممالك الثلاث

- خط زمني لفترة الممالك الثلاث

- التاريخ العسكري للممالك الثلاث

- نهاية أسرة هان

الهوامش

- ^ Roberts 1991, pg. 940

- ^ Kim, Hyung-eun (2008-07-11). "(Review) Historical China film lives up to expectations". Korea JoongAng Daily.

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms is comparable to the Bible in East Asia. It's one of the most-read if not, the most-read classics in the region.

{{cite web}}:|archive-url=is malformed: liveweb (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Shoji, Kaori (2008-11-06). "War as wisdom and gore". The Japan Times.

In East Asia, Romance is on par with the works of Shakespeare...in the same way that people in Britain grow up studying Hamlet and Macbeth.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Ng, On-cho and Q. Edward Wang (2005). Mirroring the Past: The Writing and Use of History in Imperial China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0824829131.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) p.86. - ^ Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English. Taylor & Francis. 1998. pp. 1221–1222. ISBN 1-884964-36-2. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

- ^ أ ب Lo, Kuan-chung (2002). Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Vol. 1. C.H. Brewitt-Taylor (Translator), Robert E. Hegel (Introduction). Tuttle. pp. viii. ISBN 978-0-8048-3467-4.

- ^ Moss Roberts, "Afterword," in Luo, Three Kingdoms (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), pp. 938, 964.

- ^ Roberts, pp. 946–53.

- ^ Jin, Hui-jing (December 2012). "Li Zhi and Romance of the Three Kingdoms" (in zh). Journal of University of Science and Technology Beijing (Social Sciences Edition) 26 (4): 13 – 21.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Hegel, Robert E. (2021). "Performing Li Zhi: Li Zhuowu and the Fiction Commentaries of a Fictional Commentator". In Saussy, Haun; Lee, Pauline C.; Handler-Spitz, Rivi (eds.). The objectionable Li Zhi: fiction, criticism, and dissent in late Ming China. University of Washington Press. pp. 187–208.

- ^ Hegel, Robert E. (1998). Reading illustrated fiction in the late imperial China. Publisher Stanford University Press.

- ^ Luo Guanzhong. Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Chapter 15.

- ^ Liangyan Ge, "Out of the margins: the rise of Chinese vernacular fiction", University of Hawaii Press, 2001

المصادر وقراءات إضافية

- Luo, Guanzhong (2006). Three Kingdoms. Beijing: Foreign Language Press. ISBN 7-119-00590-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Luo, Guanzhong, attributed to, translated from the Chinese with afterword and notes by Moss Roberts (1991). Three Kingdoms: A Historical Novel. Berkeley; Beijing: University of California Press; Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 0520068211.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Li Chengli. Romance of the Three Kingdoms (illustrated in English and Chinese) (2008) Asiapac Books. ISBN 978-981-229-491-3

- Besio, Kimberly Ann and Constantine Tung, eds., Three Kingdoms and Chinese Culture. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007. ISBN 0791470113. Essays on this novel's literary aspects, use of history, and in contemporary popular culture.

- Hsia, Chih-tsing,"The Romance of the Three Kingdoms," in The Classic Chinese Novel: A Critical Introduction (1968) rpr. Cornell East Asia Series. Ithaca, N.Y.: East Asia Program, Cornell University, 1996.

وصلات خارجية

- أندرو وست،The Textual History of Sanguo Yanyi The Mao Zonggang Recension, at Sanguo Yanyi 三國演義. Based on the author’s, Quest for the Urtext: The Textual Archaeology of The Three Kingdoms (PhD. Dissertation. Princeton University, 1993), and his 三國演義版本考 (Sanguo Yanyi Banben Kao Study of the Editions of The Romance of the Three Kingdoms) (Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, 1996)

- CS1 errors: markup

- CS1 errors: archive-url

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Articles containing ڤيتنامية-language text

- Articles containing كورية-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing traditional Chinese-language text

- Articles containing simplified Chinese-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2014

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from August 2015

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages with empty portal template

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- روايات القرن 14

- روايات كلاسيكية صينية

- روايات تاريخية

- أدب أسرة مينگ

- روايات تدور في هان الشرقية

- غراميات الممالك الثلاث

- Novels adapted into comics

- Chinese novels adapted into films

- Novels adapted into video games

- Chinese novels adapted into television series

- روايات تدور في Henan

- روايات تدور في Sichuan

- روايات تدور في Jiangsu

- روايات تدور في Hubei

- روايات تدور في Shaanxi

- روايات تدور في Shandong

- روايات تدور في Hebei

- روايات تدور في Jiangxi

- روايات تدور في هونان

![Illustrations from Li Zhuowu's commentary edition: "Dong Zhuo burns the Changle Palace [in Luoyang]" (left) and "Three heroes [Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei] fight Lü Bu" (right)](/w/images/thumb/3/38/Three_Kingdoms_Li_Zhuowu_edition_%E2%80%93_two_illustrations.jpg/279px-Three_Kingdoms_Li_Zhuowu_edition_%E2%80%93_two_illustrations.jpg)