توني بلير

توني بلير | |

|---|---|

Tony Blair | |

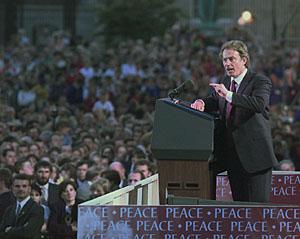

بلير في المنتدى الاقتصادي العالمي (2009) | |

| رئيس وزراء المملكة المتحدة | |

| في المنصب 2 مايو 1997 – 27 يونيو 2007 | |

| العاهل | إليزابث الثانية |

| النائب | جون پريسكوت |

| سبقه | جون ميجور |

| خلـَفه | جوردون براون |

| زعيم المعارضة | |

| في المنصب 21 يوليو 1994 – 2 مايو 1997 | |

| العاهل | إليزابث الثانية |

| رئيس الوزراء | جون ميجور |

| سبقه | مارگريت بيكيت |

| خلـَفه | جون ميجور |

| زعيم حزب العمل | |

| في المنصب 21 يوليو 1994 – 24 يونيو 2007 | |

| النائب | جون پريسكوت |

| سبقه | مارگريت بيكيت |

| خلـَفه | گوردون براون |

| وزير داخلية الظل | |

| في المنصب 24 يوليو 1992 – 24 اكتوبر 1994 | |

| الزعيم | جون سميث |

| سبقه | روي هاترسلي |

| خلـَفه | جاك سترو |

| وزير الظل للتوظيف | |

| في المنصب 2 نوفمبر 1989 – 24 يوليو 1992 | |

| الزعيم | نيل كينوك |

| سبقه | مايكل ميتشر |

| خلـَفه | فرانك دوبسون |

| وزير الظل للطاقة | |

| في المنصب 7 يونيو 1988 – 2 نوفمبر 1989 | |

| الزعيم | نيل كينوك |

| سبقه | جون پريسكوت |

| خلـَفه | فرانك دوبسون |

| عضو البرلمان عن {{{constituency_عضو البرلمان}}} | |

| في المنصب 9 يونيو 1983 – 27 يونيو 2007 | |

| سبقه | تأسيس الدائرة |

| خلـَفه | فيل ويلسون |

| الأغلبية | 18,449 (44.5%) |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | 6 مايو 1953 إدنبرة، المملكة المتحدة |

| الحزب | حزب العمل |

| الزوج | شيري بلير (1980–الآن) |

| الأنجال | إيوان نيكي كاثرين ليو |

| المدرسة الأم | كلية سانت جون، أكسفورد كلية حقوق إنز أوف كورت |

| التوقيع |  |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | مكتب توني بلير |

السير توني أنطوني تشارلز لينتون بلير (و. 6 مايو 1953)، هو سياسي بريطاني ورئيس وزراء المملكة المتحدة من عام 1997 حتى 2007 وزعيم المعارضة من حزب العمال من عام 1994 حتى 2007، وزعيم حزب العمال من عام 1994 حتى 2007. وكان زعيم المعارضة من عام 1994 حتى 1997 وتقلد عدد من المناصب الوزارية في حكومات الظل من عام 1987 حتى 1994. وكان بلير عضواً في البرلمن عن دائرة سدجفيلد من عام 1983 حتى 2007، وكان مبعوثاً خاصاً للجنة الرباعية في الشرق الأوسط من عام 2007 حتى 2015. وهو ثاني أطول رؤساء الوزراء خدمة في التاريخ البريطاني بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية بعد مارگريت ثاتشر، وأطول سياسيو حزب العمال خدمة، وهو الشخص الأول والوحيد حتى الآن الذي قاد الحزب إلى ثلاثة انتصارات متتالية في الانتخابات العامة. أسس بلير معهد توني بلير للتغيير العالمي عام 2016، ويشغل حالياً منصب رئيسه التنفيذي.

التحق بلير بمدرسة فتس كولدج المستقلة، ودرس القانون في كلية سانت جون، أكسفورد، وحصل على مؤهل محامي. انخرط في حزب العمال، وانتُخب لعضوية مجلس العموم البريطاني عام 1983 عن دائرة سدجفيلد في مقاطعة دِرَم. وبصفته نائباً غير متفرغ، دعم بلير انتقال الحزب إلى المركز السياسي في السياسة البريطانية. عُيّن في حكومة الظل برئاسة نيل كينوك عام 1988، ثم عُيّن وزيراً للداخلية في حكومة الظل برئاسة جون سميث عام 1992. بعد وفاة سميث عام 1994، فاز بلير في انتخابات زعامة الحزب ليخلفه. كزعيم، بدأ بلير عملية إعادة صياغة تاريخية للحزب، والتي عُرفت باسم "حزب العمال الجديد". أصبح بلير أصغر رئيس وزراء في القرن العشرين بعد فوز حزبه الساحق بـ 418 مقعداً (الأكبر في تاريخه) في الانتخابات العامة 1997، منهياً بذلك 18 عاماً في صفوف المعارضة. كان هذا أول انتصار لحزب العمال منذ ما يقرب من 23 عاماً، وكان آخر انتصار له في أكتوبر 1974.

خلال فترة ولايته الأولى، سنّ بلير إصلاحات دستورية، وزاد بشكل ملحوظ الإنفاق الحكومي على الرعاية الصحية والتعليم، مع إدخال إصلاحات مثيرة للجدل قائمة على السوق في هذين المجالين. كما شهد بلير طرح قانون الحد الأدنى للأجور، ورسوم التعليم العالي، والإصلاحات الدستورية مثل نقل السلطة في اسكتلندا وويلز، والتوسع الكبير في حقوق المثليين، والتقدم الملحوظ في عملية السلام في أيرلندا الشمالية مع إقرار اتفاق الجمعة العظيمة التاريخي. فيما يتعلق بالسياسة الخارجية، أشرف بلير على التدخلات البريطانية في كوسوفو عام 1999 وسيراليون عام 2000، والتي كان يُنظر إليها عموماً على أنها ناجحة.

فاز بلير بولاية ثانية بعد فوز ساحق لحزب العمال في الانتخابات العامة 2001. بعد ثلاثة أشهر من توليه منصبه، تأثرت رئاسة بلير بهجمات 11 سبتمبر، مما أدى إلى بدء الحرب على الإرهاب. دعم بلير السياسة الخارجية لإدارة جورج بوش الابن من خلال ضمان مشاركة القوات المسلحة البريطانية في حرب أفغانستان للإطاحة بحركة طالبان، وتدمير تنظيم القاعدة، والقبض على أسامة بن لادن. أيد بلير غزو العراق 2003، وجعل القوات المسلحة البريطانية تشارك في حرب العراق، على أساس اعتقاد خاطئ بأن نظام صدام حسين يمتلك أسلحة دمار شامل، وطور علاقات مع تنظيم القاعدة. كان غزو العراق مثيراً للجدل بشكل خاص، حيث اجتذب معارضة شعبية واسعة، وعارضه 139 من نواب بلير. نتيجة لذلك، واجه انتقادات بشأن السياسة نفسها وظروف القرار. قدم تقرير تحقيق العراق لعام 2016 تقييماً سلبياً لدور بلير في حرب العراق. ومع تزايد خسائر حرب العراق، اتُهم بلير بتضليل البرلمان، وانخفضت شعبيته بشكل كبير.

فاز بلير بولاية ثالثة بعد فوز حزب العمال بفوزه الانتخابي الثالث عام 2005، ويعود ذلك جزئياً إلى الأداء الاقتصادي القوي للمملكة المتحدة، لكن بأغلبية ضئيلة للغاية، بسبب تورط المملكة المتحدة في حرب العراق. خلال ولايته الثالثة، سعى بلير إلى إصلاحات أكثر شمولية في القطاع العام، وتوسط في تسوية لإعادة تقاسم السلطة في أيرلندا الشمالية. ازدادت شعبيته بشكل كبير وقت تفجيرات لندن الإرهابية في يوليو 2005، ولكن بحلول ربيع عام 2006، واجه صعوبات كبيرة، أبرزها فضائح إخفاق وزارة الداخلية في ترحيل المهاجرين غير الشرعيين. في خضم فضيحة "الأموال مقابل الشرف"، أُجريت مقابلات مع بلير ثلاث مرات بصفته رئيسًا للوزراء، ولكن كشاهد فقط وليس تحت طائلة "الحق في الصمت في إنجلترا وويلز". استمرت حربا أفغانستان والعراق، وفي عام 2006، أعلن بلير عزمه الاستقالة خلال عام. استقال من قيادة الحزب في 24 يونيو 2007، ثم من رئاسة الوزراء في 27 يونيو، وخلفه وخلفه وزير الخزانة گوردون براون.

بعد تركه رئاسة الوزراء، تخلى بلير عن مقعده في البرلمان وعُيّن مبعوثاً خاصاً للجنة الرباعية في الشرق الأوسط، وهو منصب دبلوماسي شغله حتى عام 2015. حالياً يشغل بلير منصب الرئيس التنفيذي لمعهد توني بلير للتغيير العالمي منذ عام 2016، وله تدخلات سياسية من حين لآخر، وكان له تأثير رئيسي على رئيس الوزراء البريطاني كير ستارمر. عام 2009، مُنح بلير وسام الحرية الرئاسي من جورج بوش الابن. كما مُنح وسام فارس الرباط من الملكة إليزابث الثانية عام 2022. في مراحل مختلفة من رئاسته للوزراء، كان بلير من بين أكثر السياسيين شعبية وأقلهم شعبية في التاريخ البريطاني. بصفته رئيساً للوزراء، حقق أعلى معدلات الموافقة المسجلة خلال السنوات القليلة الأولى من توليه منصبه، ولكنه حقق أيضاً واحدة من أدنى المعدلات أثناء وبعد حرب العراق.[1][2][3][4] عادة ما يُصنف بلير على أنه أعلى من المتوسط في الترتيبات التاريخية والرأي العام لرؤساء الوزراء البريطانيين.

السنوات المبكرة

وُلِد أنتوني تشارلز لينتون بلير في 6 مايو 1953 في دار كوين ماري للولادة في لوريستون، إدنبرة، اسكتلندا.[5][6][7][8] كان ثاني أبناء ليو وهازل (لقبها قبل الزواج كورسكادن) بلير.[9] كان ليو بلير ابن غير شرعي لفنانين، وقد تبناه عندما كان طفلاً عامل حوض بناء السفن في گلاسگو، جيمس بلير وزوجته ماري.[10] لأما والدته هازل كورسكادن فهي ابنة جورج كورسكادن، جزار وعضو الأخوية البرلتقالية انتقل إلى گلاسگو عام 1916. في عام 1923، عاد إلى باليشانون، مقاطعة دونگال، أيرلندا (وتوفي فيها لاحقاً). في باليشانون، أنجبت سارة مارگريت (لقبها قبل الزواج ليپست)، زوجة كورسكادن، والدة بلير، هازل، فوق متجر البقالة الخاص بالعائلة.[11][12]

لبلير أخ أكبر، وليام، وأخت صغرى، سارة. سكن بلير مع عائلته في پايزلي تـِراس بمنطقة ويلوبراي بإدنبرة. خلال هذه الفترة، عمل والده مفتشاً ضريبياً مبتدئاً أثناء دراسته للحصول على شهادة في القانون من جامعة إدنبرة.[5]

انتقل بلير لأول مرة عندما كان عمره تسعة عشر شهراً. في نهاية عام 1954، انتقل والدا بلير وابناهما من پايزلي تـِراس إلى أدليد، جنوب أستراليا.[13] كان والده محاضراً في القانون بجامعة أدليك.[14] في أستراليا، وُلدت سارة، شقيقة بلير. عاشت عائلة بلير في ضاحية دولويتش، جنوب أستراليا، بالقرب من الجامعة. عادت العائلة إلى المملكة المتحدة في منتصف عام 1958. عاشوا لفترة مع والدة هازل وزوج أمها (وليام ماكلاي) في منزلهم في ستپس، على مشارف شمال شرق گلاسگو. قبل والد بلير وظيفة محاضر في جامعة درم، وانتقل مع العائلة إلى درم عندما كان بلير في الخامسة من عمره. كانت هذه بداية علاقة طويلة الأمد بين بلير ودرم.[13]

منذ طفولته، كان بلير من مشجعي نادي نيوكاسل يونايتد لكرة القدم.[15][16][17]

التعليم ومسيرته القانونية

مع استقرار والديه في درم، التحق بلير بمدرسة كوريستر من عام 1961 حتى 1966.[18] عندما كان في الثالثة عشر من عمره، أُرسل إلى مدرسة فتس كولدج الداخلية في إدنبرة من عام 1966 حتى 1971.[19] بحسب بلير، كان يكره الفترة التي قضاها في فتس.[20] لم يكن أساتذته معجبين به؛ فقد ذكر كاتب سيرته الذاتية، جون رنتول، أن "جميع المعلمين الذين تحدثت إليهم أثناء البحث في الكتاب قالوا أنه كان مصدر إزعاج كبير وكانوا سعداء للغاية برؤيته وهو على قيد الحياة".[19] يقال إن بلير استوحى شخصيته من ميك جاگر، المغني الرئيسي لفرقة رولنگ ستونز.[21] بعد مغادرته فتس كولدج في سن الثامنة عشر، أمضى بلير عاماً فاصلاً في لندن يعمل كمروج لموسيقى الروك.[22]

عام 1972، وفي سن التاسعة عشرة، التحق بلير بكلية سانت جون، أكسفورد، ودرس فقه القضاء لثلاث سنوات.[23] عندما كان طالبًا، كان يعزف على الجيتار ويغني في فرقة روك تسمى أوگلي رومورز،[24][25] وكان يؤدي عروض كوميديا ارتجالية.[26] تأثر بلير بزميله في الدراسة، القس الأنگليكاني پيتر طومسون، الذي أيقظ إيمانه الديني وتوجهاته السياسية اليسارية. أثناء دراسته في أكسفورد، صرّح بلير بأنه كان تروتسكياً لفترة وجيزة، بعد قراءته المجلد الأول من سيرة ليون تروتسكي التي كتبها إيزاك دويتشر، والتي كانت بمثابة "ضوء ساطع".[27][28] تخرج بلير من جامعة أكسفورد عام 1975 وهو في الثانية والعشرين من عمره، بدرجة البكالوريوس في فقه القضاء مع مرتبة الشرف من الدرجة الثانية.[29][30]

عام 1975، بينما كان بلير في أكسفورد، توفيت والدته هازل عن عمر يناهز 52 عاماً بسرطان الغدة الدرقية، مما أثر عليه بشكل كبير.[31][32] بعد أكسفورد، تدرب بلير في كلية حقوق إنز أوف كورت، وهي جزء لاحق من كلية حقوق ذا سيتي[33] وتدرب على مهنة المحاماة في لنكنز إن، حيث دُعي إلى نقابة المحامين. التقى بزوجته المستقبلية، شيري بوث، في الغرف التي أسسها دري إيرفڤن، الذي كان أول مستشار قانوني لبلير.[34]

مسيرته السياسية المبكرة

انضم بلير إلى حزب العمال بعد تخرجه من جامعة أكسفورد عام 1975 بفترة وجيزة. في أوائل الثمانينيات، انخرط في العمل السياسي في منطقتي هاكني الجنوبية وشورديتش، حيث انحاز إلى تيار اليسار المعتدل في الحزب. ترشح لانتخابات مجلس هاكني عام 1982 في حي كوينزبردج، وهو منطقة آمنة لحزب العمال، لكنه لم يتم اختياره.[35]

عام 1982، أُختير بلير كمرشح لحزب العمال لمقعد المحافظين الآمن في بيكونزفيلد، حيث كانت هناك انتخابات تكميلية قادمة.[36] وعلى الرغم من خسارة بلير لانتخابات بيكونسفيلد التكميلية وانخفاض حصة حزب العمال من الأصوات بنحو عشر نقاط مئوية، فقد اكتسب مكانة مرموقة داخل الحزب.[citation needed] وعلى الرغم من هزيمته، وصف وليام رسل، المراسل السياسي لصحيفة گلاسگو هرالد، بلير بأنه "مرشح جيد للغاية"، في حين اعترف بأن النتيجة كانت "كارثية" بالنسبة لحزب العمال.[37] وعلى النقيض من وسطيته اللاحقة، أوضح بلير في رسالة كتبها إلى زعيم حزب العمال مايكل فوت في يوليو 1982 (نُشرت عام 2006) أنه "وصل إلى الاشتراكية من خلال الماركسية" واعتبر نفسه على اليسار.[38] مثل توني بين، كان بلير يعتقد أن "يمين حزب العمال" قد أفلس،[39] قائلاً "إن الاشتراكية في نهاية المطاف يجب أن تجذب أفضل عقول الناس. لا يمكنك فعل ذلك إذا كنت ملوثاً إلى حد كبير بفترة پراگماتية في السلطة".[38][39] ومع ذلك، فقد رأى أن اليسار المتشدد ليس أفضل حالاً، قائلاً:

هناك غطرسة وغرور في العديد من المجموعات في أقصى اليسار وهو أمر غير جذاب على الإطلاق للعضو العادي المحتمل... هناك الكثير من الاختلاط مع الأشخاص [مع] من يتفقون معهم فقط.[38]

مع اقتراب موعد الانتخابات العامة، لم يُختر بلير كمرشح في أي مكان. دُعي للترشح مجدداً في بيكونسفيلد، وكان ميالاً للموافقة في البداية، لكن رئيس غرفته، دري إيرڤين، نصحه بالبحث عن مكان آخر قد يكون مرشحاً فيه.[40] ازداد الوضع تعقيداً لأن حزب العمال كان يخوض معركة قانونية ضد تغييرات الحدود المخطط لها، واختار مرشحيه بناءً على الحدود السابقة. وعندما رُفض الطعن القانوني، اضطر الحزب إلى إعادة جميع الاختيارات على الحدود الجديدة؛ وكان معظمها قائمًا على المقاعد الحالية، ولكن على غير العادة في مقاطعة دورهام، أُنشئت دائرة انتخابية جديدة سدجفيلد من مناطق تصويت حزب العمال التي لم يكن لها مقعد سابق واضح.[41]

لم يبدأ اختيار سدجفيلد إلا بعد الانتخابات العامة 1983 كشفت التحقيقات الأولية لبلير أن اليسار كان يحاول ترتيب اختيار ليس هوكفيلد، النائب الحالي عن نونيتون، الذي كان يحاول في مكان آخر؛ وكان العديد من النواب الحاليين الذين شردتهم تغييرات الحدود مهتمين أيضًا بالأمر. عندما اكتشف أن فرع تريمدون لم يقدم ترشيحًا بعد، زارهم بلير وحصل على دعم سكرتير الفرع جون بيرتون، وبمساعدة بيرتون رشحه الفرع. في اللحظة الأخيرة، أُضيف اسمه إلى القائمة المختصرة وفاز بالاختيار على هوكفيلد. كان هذا آخر اختيار للمرشحين قام به حزب العمال قبل الانتخابات، وتم ذلك بعد أن أصدر حزب العمال السير الذاتية لجميع مرشحيه ("من هو من انتخابات حزب العمال").[42]

لقد أصبح جون بيرتون وكيل بلير الانتخابي وأحد حلفائه الأقدم والأكثر ثقة.[43] أيدت أدبيات بلير الانتخابية في الانتخابات العامة 1983 السياسات اليسارية التي دعا إليها حزب العمال في أوائل الثمانينيات.[44] ودعا بريطانيا إلى الخروج من السوق الأوروپية المشتركة[45] في أوائل السبعينيات،[46] على الرغم من أنه أخبر مؤتمر اختياره أنه يفضل شخصياً استمرار العضوية[citation needed] وصوّت بـ"نعم" في استفتاء عام 1975 حول عضوية المملكة المتحدة في المجموعة الأوروپية . عارض بلير آلية سعر الصرف عام 1986، لكنه أيّدها عام 1989.[47] كان عضواً في حملة نزع السلاح النووي، على الرغم من أنه لم يكن مؤيداً بقوة لنزع السلاح النووي أحادي الجانب.[48] في حملته الانتخابية حظي بلير بدعم من ممثلة المسلسلات التلفزيونية پات فينيكس، صديقة والد زوجته. وفي سن الثلاثين، انتُخب نائباً عن سدجفيلد عام 1983، على الرغم من هزيمة الحزب الساحقة في الانتخابات العامة.[citation needed]

في خطابه الأول أمام مجلس العموم في 6 يوليو 1983، صرّح بلير: "أنا اشتراكي، ليس من خلال قراءتي لكتاب مدرسي لفت انتباهي، ولا من خلال تقاليد غير مدروسة، بل لأنني أعتقد أن الاشتراكية، في أفضل حالاتها، تتوافق بشكل وثيق مع وجود عقلاني وأخلاقي. إنها تدعو إلى التعاون، لا المواجهة؛ إلى الرفقة، لا الخوف. إنها تدعو إلى المساواة".[49]

بمجرد انتخاب بلير، كان صعوده السياسي سريعاً. عينه نيل كينوك عام 1984 مساعداً للمتحدث باسم وزارة الخزانة تحت قيادة روي هاترسلي الذي كان وزير خزانة الظل.[50][51] في مايو 1985، ظهر في برنامج كوسشن تايم على بي بي سي، حيث زعم أن الكتاب الأبيض للنظام العام الصادر عن الحكومة المحافظة عام 1986 يشكل تهديداً للحريات المدنية.[52]

طالب بلير بإجراء تحقيق في قرار بنك إنگلترة بإنقاذ بنك جونسون ماثي المنهار في أكتوبر 1985. وبحلول ذلك الوقت، كان بلير منسجماً مع التوجهات الإصلاحية في الحزب وفي عام 1988 تمت ترقيته إلى فريق التجارة والصناعة في حكومة الظل كمتحدث باسم مدينة لندن.[53]

المناصب القيادية

عام 1987، ترشح بلير لانتخابات وزارة الظل، وحصل على 71 صوتاً.[54] عندما استقال كينوك بعد فوز المحافظين الرابع على التوالي في الانتخابات العامة 1992 أصبح بلير وزيراً للداخلية في حكومة الظل برئاسة جون سميث. جادل الحرس القديم بأن الاتجاهات أظهرت أنهم يستعيدون قوتهم تحت قيادة سميث القوية. في هذه الأثناء، اندمج فصيل الحزب الديمقراطي الاجتماعي المنشق مع الحزب الليبرالي؛ وبدا أن الديمقراطيين الليبراليين الناتجين يشكلون تهديداً كبيراً لقاعدة حزب العمال. كان لدى بلير، زعيم الفصيل التحديثي، رؤية مختلفة تماماً، مجادلاً بأنه يجب عكس الاتجاهات طويلة المدى. كان حزب العمال محصوراً للغاية في قاعدة آخذة في التقلص، لأنه كان يعتمد على الطبقة العاملة والنقابات العمالية وسكان المساكن المدعومة من المجلس. تم تجاهل الطبقة المتوسطة سريعة النمو إلى حد كبير، وخاصةً عائلات الطبقة العاملة الأكثر طموحاً. طمحت هذه الطبقة إلى مكانة الطبقة المتوسطة، لكنها قبلت حجة المحافظين بأن حزب العمال يعيق طموحات الطموحين بسياساته الهادفة إلى تحقيق المساواة. ونظروا بشكل متزايد إلى حزب العمال من منظور المعارضة، فيما يتعلق برفع الضرائب وأسعار الفائدة. كانت الخطوات نحو ما سيصبح حزب العمال الجديد إجرائية لكنها جوهرية. متمسكًا بشعار "عضو واحد، صوت واحد"، نجح جون سميث، بمساهمة محدودة من بلير، في إنهاء تصويت الكتلة النقابية لاختيار مرشحي وستمنستر في مؤتمر عام 1993.[55] لكن بلير والمُجددين أرادوا من سميث أن يذهب أبعد من ذلك، ودعوا إلى تعديل جذري لأهداف الحزب بإلغاء "البند الرابع"، وهو الالتزام التاريخي بتأميم الصناعة. وسيتحقق هذا عام 1995.[56]

زعيم المعارضة

توفي جون سميث فجأةً بنوبة قلبية في 12 مايو 1994، مما أدى إلى إجراء انتخابات زعامة داخل الحزب. هزم بلير كل من جون پرسكوت ومارگرت بكت في انتخابات زعامة الحزب، وأصبح بلير زعيماً للمعارضة.[57]

وكما جرت العادة بالنسبة لشاغل هذا المنصب، عُين بلير مستشاراً لمجلس الخاصة.[58] ترددت شائعات منذ فترة طويلة حول عقد صفقة بين بلير ووزير خزانة الظل گوردون براون في مطعم گرانيتا السابق في إزلنگتون، حيث وعد بلير بمنح براون السيطرة على السياسة الاقتصادية في مقابل عدم ترشح براون ضده في انتخابات زعامة الحزب.[59][60][61] سواء كان هذا صحيحاً أم لا، فإن العلاقة بين بلير وبراون كانت محورية في مصير حزب العمال الجديد، وظلا متحدين في العلن غالباً، على الرغم من الخلافات الخاصة الخطيرة التي وردت في التقارير.[62]

خلال خطابه في مؤتمر حزب العمال عام 1994، أعلن بلير عن اقتراح قادم لتحديث أهداف الحزب وأغراضه، والذي تم تفسيره على نطاق واسع على أنه يتعلق باستبدال البند الرابع من دستور الحزب ببيان جديد للأهداف والقيم.[57][63][64] وتضمن ذلك حذف التزام الحزب المعلن "بالملكية المشتركة لوسائل الإنتاج والتبادل"، وهو ما كان يُفهم عموماً على أنه يعني التأميم الشامل للصناعات الكبرى.[57][65] وفي مؤتمر خاص عقد في أبريل 1995، أُستبدل البند ببيان مفاده أن الحزب "اشتراكي ديمقراطي"،[65][66][67] وفي العام نفسه، ادعى بلير أيضاً أنه "اشتراكي ديمقراطي".[68] ومع ذلك، فإن التحرك بعيداً عن التأميم في البند الرابع القديم جعل العديد من الجناح اليساري في حزب العمال يشعرون بأن حزب العمال كان يبتعد عن المبادئ الاشتراكية التقليدية للتأميم التي وُضعت عام 1918، وكان ينظر إليهم على أنهم جزء من تحول الحزب نحو "حزب العمال الجديد".[69]

ورث بلير زعامة حزب العمال في وقت كان فيه الحزب متفوقاً على المحافظين في استطلاعات الرأي، منذ تراجع سمعة الحكومة المحافظة في السياسة النقدية نتيجة لكارثة الأربعاء الأسود الاقتصادية في سبتمبر 1992. وشهد انتخاب بلير كزعيم ارتفاعاً في دعم حزب العمال[70] على الرغم من التعافي الاقتصادي المستمر وانخفاض معدلات البطالة التي أشرفت عليها حكومة جون ميجور المحافظة منذ نهاية الركود الاقتصادي الذي شهدته البلاد في الفترة 1990-1992.[70] في مؤتمر حزب العمال عام 1996، ذكر بلير أن أولوياته الثلاث عند توليه منصبه هي "التعليم، ثم التعليم، ثم التعليم".[71]

وبمساعدة عدم شعبية حكومة جون ميجور المحافظة، التي كانت منقسمة بشدة بشأن الاتحاد الأوروپي،[72] حقق بلير فوزاً ساحقاً لحزب العمال في الانتخابات العامة 1997، منهياً بذلك ثمانية عشر عاماً من حكومة حزب المحافظين، مع أكبر هزيمة للمحافظين منذ 1906.[73]

عام 1996، نُشر البيان السياسي حزب العمال الجديد، حياة جديدة لبريطانيا، الذي حدد نهج الحزب الجديد "الطريق الثالث" الوسطي في السياسة، وقُدّم على أنه نموذج لحزب مُصلح حديثاً عدّل البند الرابع من الدستور، وأيد اقتصاد السوق. في مايو 1995، حقق حزب العمال نجاحاً كبيراً في الانتخابات المحلية والأوروپية، وفاز بأربع انتخابات فرعية. بالنسبة لبلير، كانت هذه الإنجازات مصدر تفاؤل، إذ أشارت إلى تراجع شعبية المحافظين. وقد وضعت جميع استطلاعات الرأي تقريبًا منذ أواخر عام 1992 حزب العمال في صدارة المحافظين، مع حصوله على دعم كافي لتشكيل أغلبية مطلقة.[74]

رئيس الوزراء (1997–2007)

أصبح بلير رئيس وزراء المملكة المتحدة في 2 مايو 1997؛ وكان عمره 43 عاماً، وكان أصغر شخص يصل إلى هذا المنصب بعد أن أصبح لورد ليڤرپول رئيساً للوزراء في سن 42 عاماً، عام 1812.[75] وكان أيضاً أول رئيس وزراء يُولد بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية وتولي إليزابث الثانية العرش. وبانتصاراته في أعوام 1997 و2001 و2005، كان بلير رئيس وزراء الأطول خدمةً من حزب العمال،[76] وأول شخص يقود الحزب إلى ثلاثة انتصارات متتالية في الانتخابات العامة.[77]

أيرلندا الشمالية

حظيت مساهمة بلير في عملية السلام في أيرلندا الشمالية من خلال المساعدة في التفاوض على اتفاق الجمعة العظيمة باعتراف واسع النطاق.[78][79] في أعقاب تفجير أوما في 15 أغسطس 1998، الذي نفذه أعضاء الجيش الجمهوري الأيرلندي الحقيقي المعارض لعملية السلام، والذي أسفر عن مقتل 29 شخصاً وإصابة المئات، زار بلير بلدة مقاطعة تايرون والتقى بالضحايا في مستشفى رويال ڤيكتوريا، بلفاست.[80]

المشاركة العسكرية في الحرب على الإرهاب

خلال سنواته الست الأولى في منصبه، أمر بلير القوات البريطانية بالقتال خمس مرات، وهو عدد أكبر من أي رئيس وزراء آخر في تاريخ بريطانيا. وشمل ذلك العراق في كل من 1998 و2003، وكوسوڤو (1999)، وسيراليون (2000)، وأفغانستان (2001).[81]

حرب كوسوڤو، التي دافع عنها بلير لأسباب أخلاقية، كانت فاشلة في البداية لاعتمادها على الضربات الجوية فقط؛ وأقنع التهديد بهجوم بري الرئيس الصربي سلوبودان ميلوشڤتش، بالانسحاب. كان بلير من أشد المؤيدين لشن هجوم بري، وهو ما تردد الرئيس الأمريكي بيل كلنتون في القيام به، وأمر بتجهيز 50.000 جندي - معظم الجيش البريطاني المتاح - للحرب.[82] وفي العام التالي، أدت العملية پاليسر المحدودة في سيراليون إلى تحويل مجرى الأمور ضد القوات المتمردة بسرعة؛ فقبل نشرها، كانت بعثة الأمم المتحدة في سيراليون على وشك الانهيار.[83] كان من المقرر أن تكون پاليسر بمثابة مهمة إخلاء، لكن العميد ديڤد رتشاردز تمكن من إقناع بلير بالسماح له بتوسيع دوره؛ في ذلك الوقت، لم يكن تصرف رتشاردز معروفاً، وكان من المفترض أن بلير كان وراء ذلك.[84]

أمر بلير بتنفيذ العملية باراس، وهي ضربة ناجحة للغاية لقوات الخدمة الجوية الخاصة/فوج المظلات لإنقاذ رهائن من جماعة متمردة في سيراليون.[85] وقد زعم الصحفي أندرو مار أن نجاح الهجمات البرية، الحقيقية والمهددة، مقارنة بالضربات الجوية وحدها كان مؤثراً على كيفية تخطيط بلير لحرب العراق، وأن نجاح الحروب الثلاث الأولى التي خاضها بلير "لعب على إحساسه بنفسه كزعيم حرب أخلاقي".[86] وعندما سُئل عام 2010 عما إذا كان نجاح پاليسر قد "شجع السياسيين البريطانيين" على التفكير في العمل العسكري كخيار سياسي، أقر الجنرال السير ديڤد رتشاردز بأن "هذا قد يكون شيئاً إيجابياً".[84]

منذ بداية الحرب على الإرهاب عام 2001، أيّد بلير بشدة السياسة الخارجية التي انتهجها جورج بوش الابن، وشارك في غزو أفغانستان 2001 وغزو العراق 2003. كان غزو العراق مثيراً للجدل بشكل خاص، إذ استقطب معارضة شعبية واسعة، وعارضه 139 من نواب بلير.[87] نتيجة لذلك، واجه انتقاداتٍ بشأن السياسة نفسها وظروف القرار. وصف ألستير كامبل تصريح بلير بأن المعلومات المخابراتية المتعلقة بأسلحة الدمار الشامل "لا شك فيها" بأنه "تقييمه للتقييم الذي قُدِّم له".[88] عام 2009، صرح بلير أنه كان سيؤيد إسقاط نظام صدام حسين حتى في مواجهة الدليل على أنه لا يمتلك مثل هذه الأسلحة.[89] اتهم الكاتب المسرحي هارولد پنتر ورئيس الوزراء الماليزي السابق مهاتير محمد بلير بارتكاب جرائم حرب.[90][91]

وفي شهادته أمام لجنة التحقيق في حرب العراق في 29 يناير 2010، قال بلير إن صدام حسين كان "وحشاً، وأعتقد أنه لم يكن يهدد المنطقة فحسب بل والعالم أيضاً".[92] قال بلير إن الموقف البريطاني والأمريكي تجاه صدام حسين قد "تغير جذرياً" بعد هجمات 11 سبتمبر. ونفى بلير أنه كان سيؤيد غزو العراق حتى لو كان يعتقد أن صدام حسين لا يمتلك أسلحة دمار شامل. وقال أنه يعتقد أن العالم أصبح أكثر أماناً نتيجة الغزو.[93] وقال أنه "لا يوجد فرق حقيقي بين الرغبة في تغيير النظام والرغبة في نزع سلاح العراق: إن تغيير النظام كان سياسة الولايات المتحدة لأن العراق كان ينتهك التزاماته تجاه الأمم المتحدة".[94]

في مقابلة مع فريد زكريا أجرته سي إن إن في أكتوبر 2015، اعتذر بلير عن "أخطائه" بشأن حرب العراق واعترف بوجود "عناصر من الحقيقة" في الرأي القائل بأن الغزو ساعد في تعزيز صعود الدولة الإسلامية (داعش).[95]

أعطى تقرير تحقيق حرب العراق 2016 تقييماً مدمراً لدور بلير في حرب العراق، على الرغم من أن رئيس الوزراء السابق رفض مرة أخرى الاعتذار عن قراره بدعم الغزو الذي قادته الولايات المتحدة.[96]

علاقته بالبرلمان

كان من أوائل قرارات بلير كرئيس للوزراء استبدال جلسات أسئلة رئيس الوزراء التي كانت تُعقد مرتين أسبوعياً، كل منها مدته 15 دقيقة، يومي الثلاثاء والخميس، بجلسة واحدة مدتها 30 دقيقة يوم الأربعاء. بالإضافة إلى هذه الجلسات، كان بلير يعقد مؤتمرات صحفية شهرية يجيب فيها على أسئلة الصحفيين،[97] ومنذ عام 2002، خالف السابقة بالموافقة على الإدلاء بشهادته مرتين سنوياً أمام أعلى لجنة مختارة في مجلس العموم، وهي لجنة الاتصال.[98] كان يُنظر إلى بلير في بعض الأحيان على أنه لا يولي اهتماماً كافياً لآراء زملائه في مجلس الوزراء وآراء مجلس العموم.[99][100] أُنتقد بلير في بعض الأحيان بأنه لا يتمتع بأسلوب رئيس وزراء ورئيس حكومة، وهو ما كان عليه، بل أسلوب رئيس ورأس دولة، وهو ما لم يكن عليه.[101] واتهم بلير بالاعتماد المفرط على التضليل السياسي.[102][103] كان بلير أول رئيس وزراء للمملكة المتحدة يُستجوب رسمياً من قبل الشرطة، رغم أنه لم يكن تحت التحذير، أثناء وجوده في منصبه.[104]

أحداث قبل الاستقالة

ومع تزايد خسائر حرب العراق، اتُهم بلير بتضليل البرلمان،[105][106] وتراجعت شعبيته نتيجة لذلك،[107][108] مع تراجع الأغلبية الإجمالية لحزب العمال في انتخابات 2005 من 167 إلى 66 مقعداً. ونتيجةً لاتفاق بلير-براون، وحرب العراق، وانخفاض نسب التأييد، ازداد الضغط داخل حزب العمال لاستقالة بلير.[109] خلال صيف 2006، انتقد العديد من أعضاء البرلمان بلير لعدم دعوته إلى وقف إطلاق النار في الصراع الإسرائيلي اللبناني.[110] في 7 سبتمبر 2006، أعلن بلير عزمه التنحي عن منصبه كزعيم بحلول موعد مؤتمر النقابات العمالية الذي عقد في 10-13 سبتمبر 2007،[111] على الرغم من وعده بإكمال فترة ولايته خلال حملة الانتخابات العامة السابقة. في 10 مايو 2007، وخلال خطاب ألقاه في نادي العمال في تريمدون، أعلن بلير عزمه الاستقالة من منصبه كزعيم لحزب العمال ورئيس للوزراء،[112] مما عجل بانتخابات الزعامة التي كان براون المرشح الوحيد فيها.[113]

وفي مؤتمر خاص للحزب عقد في مانشستر في 24 يونيو 2007، سلم بلير رسمياً قيادة حزب العمال إلى براون، الذي كان يشغل منصب وزير الخزانة في وزارات بلير الثلاث.[114] قدّم بلير استقالته من رئاسة الوزراء في 27 يونيو، وتولى براون منصبه في عصر اليوم نفسه. استقال بلير من مقعده البرلماني عن دائرة سدجفيلد بالطريقة التقليدية، بقبوله منصب رعاية تشيلترن هاندردز، الذي عيّنه براون فيه في أحد آخر قراراته كوزير للخزانة؛[115] فاز مرشح حزب العمال فيل ويلسون في الانتخابات التكميلية.[116] قرر بلير عدم إصدار قائمة أوسمة الاستقالة، مما جعله أول رئيس وزراء في العصر الحديث لا يفعل ذلك.[117]

سياساته

عام 2001، قال بلير: "نحن حزب يساري-وسطي، نسعى إلى تحقيق الرخاء الاقتصادي والعدالة الاجتماعية كشركاء وليس كمتضادِّين".[118] نادراً ما يطلق بلير مثل هذه التسميات على نفسه؛ فقد وعد قبل انتخابات 1997 بأن حزب العمال الجديد سيحكم "من الوسط الراديكالي"، ووفقاً لأحد أعضاء حزب العمال مدى الحياة، فقد وصف بلير نفسه دائماً بأنه ديمقراطي اشتراكي.[119] في مقال رأي نشرته الگارديان عام 2007، وصف المعلق اليساري نيل لوسون بلير بأنه من يميني-وسطي.[120] أظهر استطلاع للرأي أجرته يوگوڤ عام 2005 أن أغلبية صغيرة من الناخبين البريطانيين، بما في ذلك العديد من أنصار حزب العمال الجديد، وضعوا بلير على يمين الطيف السياسي.[121] وزعمت فايننشال تايمز أن بلير ليس محافظاً، بل هو "شعبوياً".[122]

يميل النقاد والمعجبون إلى الاتفاق على أن نجاح بلير الانتخابي استند إلى قدرته على احتلال مركز الوسط وجذب الناخبين من مختلف الأطياف السياسية، لدرجة أنه كان على خلاف جوهري مع قيم حزب العمال التقليدية. جادل بعض النقاد اليساريين، مثل مايك ماركوسي عام 2001، بأن بلير أشرف على المرحلة الأخيرة من تحول طويل الأمد لحزب العمال نحو اليمين.[123]

هناك بعض الأدلة التي تشير إلى أن هيمنة بلير طويلة الأمد على الوسط أجبرت معارضيه المحافظين على التحول مسافة كبيرة نحو اليسار لتحدي هيمنته هناك.[124] كان المحافظون البارزون في حقبة ما بعد حزب العمال الجديد يكنون لبلير احتراماً كبيراً: فقد وصفه جورج أوزبورن بأنه "السيد"، بينما صرح مايكل گوڤ في فبراير 2003 أنه "يستحق احترام المحافظين"، في حين ورد أن ديڤد كامرون أبقى على بلير كمستشار غير رسمي.[125][126][127] أعلنت رئيسة الوزراء السابقة من حزب المحافظين مارگريت ثاتشر أن بلير وحزب العمال الجديد هما أعظم إنجازاتها.[128]

الإصلاحات الاجتماعية

أدخل بلير إصلاحات دستورية هامة؛ وعزز حقوقاً جديدة للمثليين؛ ووقع معاهدات تُعزز تكامل المملكة المتحدة مع الاتحاد الأوروپي. وفيما يتعلق تحديداً بإصلاحاته المتعلقة بمجتمع المثليين، قدم بلير قانون الشراكة المدنية 2004 الذي منح الشركاء المدنيين حقوقاً ومسؤوليات مماثلة لتلك الموجودة في الزواج المدني، وساوى سن الرشد بين الأزواج المغايرين والمثليين، وأنهى حظر خدمة المثليين في الجيش البريطاني، وطرح قانون الاعتراف بالجندر 2004 الذي يسمح لمن يعانون من اضطراب الهوية الجنسية بتغيير نوعهم قانونياً، وألغى المادة 28، ومنح الأزواج المثليين الحق في التبني، وسنّ العديد من سياسات مكافحة التمييز. عام 2014، وصفته صحيفة جاي تايمز بأنه "رمز للمثليين".[129]

عملت حكومة حزب العمال الجديدة على زيادة صلاحيات الشرطة من خلال إضافة عدد من الجرائم التي تستوجب الاعتقال، والتسجيل الإلزامي للحمض النووي واستخدام أوامر الفصل.[130] في ظل حكومة بلير، زادت كمية التشريعات الجديدة[131] الذي أثار الكثير من النقد.[132] كما طرح تشريعات صارمة لمكافحة الإرهاب وتشريعات بطاقات الهوية.[citation needed]

السياسات الاقتصادية

يُنسب إلى بلير الإشراف على اقتصاد قوي، حيث نمى الدخل الحقيقي للمواطنين البريطانيين بنسبة 18% بين عامي 1997 و2006. وشهدت بريطانيا نمواً سريعاً في الإنتاجية ونمواً ملحوظاً في الناتج المحلي الإجمالي، بالإضافة إلى انخفاض معدلات الفقر وعدم المساواة، والتي، على الرغم من إصرارها على عدم انخفاضها، توقفت بفضل السياسات الاقتصادية لحزب العمال الجديد (مثل الإعفاءات الضريبية). وعلى الرغم من تنامي الفقاعة المالية في أسواق العقارات، فقد عزت الدراسات هذا النمو إلى الاستثمارات في التعليم والحفاظ على المسؤولية المالية، وليس إلى ارتفاع مستوى السكر في الدم.[133]

خلال فترة توليه منصب رئيس الوزراء، أبقى بلير الضرائب المباشرة منخفضة، في حين رفع الضرائب غير المباشرة؛ واستثمر مبلغاً كبيراً في رأس المال البشري؛ وطرح الحد الأدنى للأجور الوطنية وبعض حقوق العمل الجديدة (مع الحفاظ على إصلاحات مارگريت ثاتشر النقابية).[134] أدخل بلير إصلاحات جوهرية قائمة على السوق في قطاعي التعليم والصحة؛ وفرض رسوماً دراسية على الطلبة؛ وقدّم برنامجاً للرعاية الاجتماعية للعمل، وسعى إلى خفض فئات معينة من مدفوعات الرعاية الاجتماعية. لم يُلغِ أثر خصخصة السكك الحديدية البريطانية التي سنّها سلفه جون ميجور، بل عزز التنظيم (بإنشاء مكتب تنظيم السكك الحديدية) وحدد ارتفاعات الأجرة بحيث لا يتجاوز مؤشر أسعار التجزئة 1%.[135][136][137]

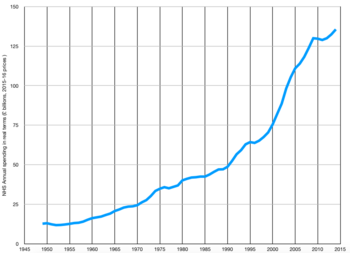

قام بلير وبراون بزيادة الإنفاق على هيئة الصحة الوطنية وغيرها من الخدمات العامة، مما أدى إلى زيادة الإنفاق من 39.9% من الناتج المحلي الإجمالي إلى 48.1% في عامي 2010 و2011.[139][140] وقد تعهدا عام 2001 برفع إنفاق هيئة الصحة الوطنية إلى مستويات البلدان الأوروپية الأخرى، وضاعفا الإنفاق من حيث القيمة الحقيقية إلى أكثر من 100 بليون جنيه إسترليني في إنگلترة وحدها.[141]

الهجرة

ارتفعت الهجرة غير الأوروپية بشكل ملحوظ خلال الفترة من عام 1997، ويرجع ذلك جزئياً إلى إلغاء حكومة بلير الأولى لقاعدة الغرض الأساسي في يونيو 1997.[142] سهّل هذا التغيير على المقيمين في المملكة المتحدة جلب أزواجهم/زوجاتهم الأجانب إلى البلاد. صرّح المستشار الحكومي السابق أندرو نيذر في صحيفة إيڤننگ ستاندرد بأن السياسة المتعمدة للوزراء من أواخر عام 2000 حتى أوائل عام 2008 كانت فتح المملكة المتحدة أمام الهجرة الجماعية.[143][144] صرح نيذر لاحقاً بأن كلماته قد حُرفت، قائلاً: "كان الهدف الرئيسي هو السماح بدخول المزيد من العمال المهاجرين في وقت - يصعب تصوره الآن - كان الاقتصاد المزدهر يواجه نقصاً في المهارات... بطريقةٍ ما، تم تحريف هذا من قِبل كتاب الأعمدة الصحافيين اليمينيين المتحمسين، ليُصبح 'مؤامرة' لجعل بريطانيا متعددة الثقافات. لم تكن هناك أي مؤامرة".[145]

السجل البيئي

انتقد بلير الحكومات الأخرى لتقصيرها في حل مشكلة تغير المناخ العالمي. وفي زيارة للولايات المتحدة عام 1997، علّق على "الدول الصناعية الكبرى" التي تفشل في خفض انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة. وفي عام 2003، مثّل بلير أمام الكونگرس الأمريكي، وقال أنه "لا يمكن تجاهل تغير المناخ"، مصراً على "ضرورة تجاوز كيوتو".[146] وعد بلير وحزبه بخفض انبعاثات ثاني أكسيد الكربون بنسبة 20%.[147] كما زعم حزب العمال أنه بحلول عام 2010 سوف يأتي 10% من الطاقة من مصادر متجددة؛ إلا أنها لم تصل إلا إلى 7% بحلول تلك النقطة.[148]

عام 2000، خصص بلير 100 مليون يورو للسياسات الخضراء، وحث أنصار البيئة وقطاع الأعمال على العمل معاً.[149]

السياسة الخارجية

بنى بلير سياسته الخارجية على مبادئ أساسية (علاقات وثيقة مع الولايات المتحدة والاتحاد الأوروپي)، وأضاف إليها فلسفةً جديدةً ناشطةً هي "التدخلية". في عام 2001، انضمت بريطانيا إلى الولايات المتحدة في الحرب العالمية على الإرهاب.[150]

أقام بلير صداقات مع العديد من الزعماء الأوروپيين، بما في ذلك رئيس الوزراء الإيطالي سيلڤيو برلوسكوني،[151] المستشارة الألمانية أنگلا مركل،[152] وأخيراً الرئيس الفرنسي نيكولا ساركوزي.[153]

إلى جانب علاقته الوثيقة ببيل كلنتون، شكّل بلير تحالفاً سياسياً قوياً مع جورج بوش الابن، لا سيما في مجال السياسة الخارجية. من جانبه، أشاد بوش ببلير والمملكة المتحدة. ففي خطابه ما بعد أحداث 11 سبتمبر، على سبيل المثال، صرّح قائلاً: "ليس لأمريكا صديق أصدق من بريطانيا العظمى".[154]

لقد ألحق التحالف بين بوش وبلير ضرراً بالغاً بمكانة بلير في نظر البريطانيين الغاضبين من النفوذ الأمريكي؛[155] كشف استطلاع للرأي أجري عام 2002 أن عدداً كبيراً من البريطانيين ينظرون إلى بلير باعتباره "كلب بوش المدلل".[156] وقال بلير إن من مصلحة بريطانيا "حماية وتعزيز الروابط" مع الولايات المتحدة بغض النظر عمن يتولى السلطة في البيت الأبيض.[157]

ومع ذلك، فإن تصور التقارب الشخصي والسياسي من جانب واحد أدى إلى مناقشة مصطلح "الكلب-المدلل" في وسائل الإعلام في المملكة المتحدة، لوصف "العلاقة الخاصة" بين حكومة ورئيس وزراء المملكة المتحدة مع البيت الأبيض والرئيس الأمريكي.[158] تم تسجيل محادثة مكشوفة بين بوش وبلير، حيث خاطب الأول الثاني باسم "يا [أو نعم]، بلير" عندما لم يكونا على علم بوجود ميكروفون مباشر في قمة مجموعة الثماني التي عُقدت في سانت پطرسبورگ عام 2006.[159]

الشرق الأوسط

في 30 يناير 2003، وقع بلير على رسالة الثمانية التي تدعم السياسة الأمريكية تجاه العراق.[160]

أظهر بلير شعوراً عميقاً تجاه إسرائيل، والذي ينبع جزئياً من إيمانه.[161] كان بلير قديماً لفترة في جماعة الضغط المؤيدة لإسرائيل، أصدقاء حزب العمال لإسرائيل.[162]

عام 1994، أقام بلير علاقات وثيقة مع مايكل لـِڤي، أحد زعماء مجلس القيادة اليهودي.[163] أدار لـِڤي صندوق مكتب زعيم حزب العمال لتمويل حملة بلير قبل انتخابات عام 1997، وجمع 12 مليون جنيه إسترليني لتحقيق فوز ساحق لحزب العمال. وكافأه بلير بلقب نبيل مدى الحياة، وفي عام 2002، عيّنه بلير مبعوثاً شخصياً إلى الشرق الأوسط. وأشاد لـِڤي ببلير على "دعمه الراسخ والملتزم لدولة إسرائيل".[164] عام 2003، اقترح تام دالييل، بينما كان أب مجلس العموم، أن قرارات بلير في مجال السياسة الخارجية كانت متأثرة بشكل غير ملائم "بعصابة" من المستشارين اليهود، بما في ذلك لـِڤي ، وپيتر ماندلسون وجاك سترو (الاثنان الأخيران ليسا يهوديين لكن لديهما بعض الأصول اليهودية).[165]

كان بلير، عند توليه منصبه، "بارداً في تعامله مع حكومة نتنياهو اليمينية".[166] During his first visit to Israel, Blair thought the Israelis bugged him in his car.[167] وبعد انتخاب إيهود باراك عام 1999، والذي أقام معه بلير علاقة وثيقة، أصبح أكثر تعاطفاً مع إسرائيل.[166] منذ عام 2001، بنى بلير علاقات [مطلوب توضيح] مع خليفة باراك، أرييل شارون، واستجاب بشكل إيجابي لياسر عرفات، الذي التقى به ثلاث عشرة مرة منذ أن أصبح بلير رئيساً للوزراء واعتبره ضرورياً للمفاوضات المستقبلية.[166] عام 2004، صرح خمسون دبلوماسياً سابقاً، بمن فيهم سفراء في بغداد وتل أبيب، بأنهم "راقبوا بقلق متزايد" بريطانيا وهي تتبع الولايات المتحدة في حرب العراق 2003. وانتقدوا دعم بلير لخارطة الطريق التي تضمنت الاحتفاظ بالمستوطنات الإسرائيلية في الضفة الغربية.[168]

عام 2006 تعرض بلير لانتقادات بسبب فشله في الدعوة فوراً إلى وقف إطلاق النار في حرب لبنان 2006 وزعمت الأوبزرڤر أنه في اجتماع لمجلس الوزراء قبل أن يغادر بلير إلى قمة مع بوش في 28 يوليو 2006، ضغط عدد كبير من الوزراء على بلير لانتقاد إسرائيل علناً بسبب حجم القتلى والدمار في لبنان.[169]

تعرض بلير لانتقادات بسبب موقفه الثابت إلى جانب الرئيس الأمريكي جورج بوش الابن بشأن سياسة الشرق الأوسط.[170]

سوريا وليبيا

كشف طلب للحصول على معلوماتٍ قدمته صحيفة صنداي تايمز عام 2012 بموجب قانون حرية المعلومات أن حكومة بلير درست منح الرئيس السوري بشار الأسد لقب فارس. وأظهرت الوثائق أن بلير كان مستعداً للظهور إلى جانب الأسد في مؤتمر صحفي مشترك، رغم أن السوريين كانوا سيكتفون على الأرجح بمصافحة وداع أمام الكاميرات؛ وسعى المسؤولون البريطانيون إلى التلاعب بوسائل الإعلام لتصوير الأسد بصورةٍ إيجابية؛ وحاول مساعدو بلير مساعدة زوجة الأسد "الجذابة في التصوير" أسماء الأسد على تعزيز مكانتها. وأشارت الصحيفة إلى:

حظي الزعيم العربي بلقاءات مع الملكة وأمير ويلز، وتناول الغداء مع بلير في داوننگ ستريت، وحصل على منصة في البرلمان والعديد من الامتيازات الأخرى... إن المعاملة الراقية التي حظي بها هو وحاشيته محرجة للغاية بالنظر إلى حمام الدم الذي حدث منذ ذلك الحين في ظل حكمه في سوريا... إن هذه الخطوبة تشبه العلاقات الودية التي كانت تربط بلير بمعمر القذافي.[171]

كان بلير على علاقة ودية مع الزعيم الليبي معمر القذافي، عندما رفعت الولايات المتحدة والمملكة المتحدة العقوبات المفروضة على البلاد.[172][173]

كان بلير على علاقة ودية مع الزعيم الليبي معمر القذافي، عندما رفعت الولايات المتحدة والمملكة المتحدة العقوبات المفروضة على البلاد.[174] خلال رئاسة بلير للوزراء، سلمت المخابرات البريطانية عبد الحكيم بلحاج إلى نظام القذافي عام 2004، على الرغم من أن بلير زعم لاحقاً أنه "لا يتذكر" الحادث.[175]

زيمبابوي

كانت علاقة بلير مع رئيس زيمبابوي روبرت موگابى عدائية، ويُزعم أنه خطط لتغيير نظام موگابى في أوائل ع. 2000.[176] شرعت زيمبابوي في برنامج إعادة توزيع الأراضي دون تعويض من المزارعين التجاريين البيض في البلاد إلى السكان السود، وهي سياسة عطّلت الإنتاج الزراعي ودفعت اقتصاد زيمبابوي إلى حالة من الفوضى. كشف الجنرال تشارلز گثري، رئيس أركان الدفاع، عام 2007 أنه وبلير ناقشا غزو زيمبابوي.[177] أوصى گثري بعدم اللجوء إلى العمل العسكري، قائلاً: "اصبروا، لأن ذلك سيجعل الأمور أسوأ".[177] في عام 2013، صرّح الرئيس الجنوب أفريقي ثابو مبيكي أن بلير ضغط على جنوب أفريقيا للانضمام إلى "مخطط لتغيير النظام، حتى أنه وصل إلى حد استخدام القوة العسكرية" في زيمبابوي.[176] ورفض مبيكي ذلك لأنه شعر بأن "موگابي هو جزء من حل هذه المشكلة".[176] لكن متحدثاً باسم بلير قال أنه "لم يطلب من أحد قط التخطيط أو المشاركة في أي تدخل عسكري من هذا القبيل".[176]

روسيا

عام 2000، سافر بلير إلى موسكو لحضور عرض لأوپرا الحرب والسلام مع ڤلاديمير پوتن، عندما كان رئيساً لروسيا بالإنابة. وقد انتقدت منظمات مثل هيومان رايتس واتش ومنظمة العفو الدولية هذا اللقاء.[178] عام 2018، صرّح السير رتشارد ديرلوڤ، الرئيس السابق لمصلحة المخابرات السرية البريطانية (MI6)، أن هناك "ندم شديد" على هذه الرحلة التي ساعدت پوتين على الوصول إلى السلطة. وزعم ديرلوڤ أيضاً أنه في عام 2000، تواصل معه ضابط من المخابرات السوڤيتية ، طالباً مساعدة بريطانيا في تعزيز مكانة پوتن السياسية، ولهذا السبب التقى بلير بپوتن في روسيا.[179]

في أبريل 2000 استضاف بلير پوتين في لندن، رغم تردد قادة العالم الآخرين تجاهه، ومعارضة منظمات حقوق الإنسان لجرائم الحرب الشيشانية الثانية والإرهاب المرتكبة في الشيشان. وصرح بلير لجيم هوگلاند من واشنطن پوست أن "رؤية پوتن للمستقبل هي رؤية نرتاح لها. فلدى پوتن أجندة واضحة جداً لتحديث روسيا. وعندما يتحدث عن روسيا قوية، فإنه لا يعني القوة التي تُهدد، بل تعني أن البلاد قادرة اقتصادياً وسياسياً على الدفاع عن نفسها، وهو هدف نبيل".[180][181] خلال الاجتماع، اعترف بلير وناقش "المخاوف بشأن الشيشان"،[182][183] لكنه وصف پوتن بالمصلح السياسي "المستعد لتبني علاقة جديدة مع الاتحاد الأوروپي والولايات المتحدة، ويريد روسيا قوية وحديثة وعلاقة قوية مع الغرب".[184][185]

علاقته بالإعلام

روپرت مردوخ

عام 2006، أفادت الگارديان أن بلير كان يحظى بدعم سياسي من روپرت مردوخ، مؤسس مؤسسة نيوز كورپوريشن.[186] في عام 2011، أصبح بلير الأب الروحي لأحد أطفال مردوخ من وندي دنگ،[187] لكن صداقتهما انتهت فيما بعد في عام 2014، بعد أن اشتبه مردوخ في أنه كان على علاقة غرامية مع دنگ بينما كانا لا يزالان متزوجين، وفقاً للإكونومست.[188][189][190][191][مطلوب مصدر أفضل]

تواصله مع أصحاب وسائل الإعلام البريطانية

A Cabinet Office freedom of information response, released the day after Blair handed over power to Gordon Brown, documents Blair having various official phone calls and meetings with Rupert Murdoch of News Corporation and Richard Desmond of Northern and Shell Media.[192]

The response includes contacts "clearly of an official nature" in the specified period, but excludes contacts "not clearly of an official nature."[193] No details were given of the subjects discussed. In the period between September 2002 and April 2005, Blair and Murdoch are documented speaking six times; three times in the nine days before the Iraq War, including the eve of the 20 March US and UK invasion, and on 29 January, 25 April, and 3 October 2004. Between January 2003 and February 2004, Blair had three meetings with Richard Desmond; on 29 January and 3 September 2003, and 23 February 2004.[194]

The information was disclosed after a 31⁄2-year battle by the Liberal Democrats' Lord Avebury.[192] Lord Avebury's initial October 2003 information request was dismissed by then leader of the Lords, Baroness Amos.[192] A following complaint was rejected, with Downing Street claiming the information compromised "free and frank discussions", while Cabinet Office claimed releasing the timing of the PM's contacts with individuals is "undesirable", as it might lead to the content of the discussions being disclosed.[192] While awaiting a following appeal from Lord Avebury, the cabinet office announced that it would release the information. Lord Avebury said: "The public can now scrutinise the timing of his (Murdoch's) contacts with the former prime minister, to see whether they can be linked to events in the outside world."[192]

Blair appeared before the Leveson Inquiry on Monday 28 May 2012.[195] During his appearance, a protester, later named as David Lawley-Wakelin, got into the court-room and claimed he was guilty of war crimes before being dragged out.[196]

صورته في الإعلام

اشتهر بلير بأنه متحدث كاريزمي وواضح وذو أسلوب غير رسمي.[57] قال المخرج السينمائي والمسرحي رتشارد إير إن "بلير يتمتع بمهارة كبيرة كممثل".[197] بعد بضعة أشهر من توليه منصب رئيس الوزراء، ألقى بلير كلمة تكريمية للأميرة ديانا، صباح يوم وفاتها في أغسطس 1997، حيث وصفها بأنها "أميرة الشعب".[198][199]

بعد توليه منصبه عام 1997، أولى بلير أهمية خاصة لسكرتيره الصحفي، الذي عُرف بالمتحدث الرسمي باسم رئيس الوزراء (وقد فُصل الدوران منذ ذلك الحين). وكان أليستير كامبل أول من شغل هذا المنصب في عهد بلير، حيث شغله من مايو 1997 حتى 8 يونيو 2001، ثم شغل منصب مدير الاتصالات والاستراتيجية في مكتب رئيس الوزراء حتى استقالته في 29 أغسطس 2003 في أعقاب تحقيق هوتون.[200]

كانت لبلير علاقات وثيقة مع عائلة كلنتون. وقد تجسدت هذه الشراكة القوية مع بيل كلنتون في فيلم العلاقة الخاصة عام 2010.[201]

علاقته بحزب العمال

انتقدت الصحافة البريطانية وأعضاء البرلمان رفض بلير الواضح لتحديد موعد رحيله. وأفادت التقارير أن عدداً من الوزراء يعتقدون أن رحيل بلير في الوقت المناسب من منصبه سيكون ضرورياً للفوز في انتخابات رابعة.[202] اعتبر بعض الوزراء أن إعلان بلير عن المبادرات السياسية في سبتمبر 2006 بمثابة محاولة لصرف الانتباه عن هذه القضايا.[202]

گوردون براون

بعد وفاة جون سميث عام 1994، أصبح بلير وزميله المقرب گوردون براون (الذي تقاسما مكتباً في مجلس العموم[57]) يُنظر إليهما كمرشحين محتملين لقيادة الحزب. واتفقا على عدم التنافس، كما يُقال، كجزء من تحالف مزعوم بين بلير وبراون. أدرك براون، الذي اعتبر نفسه الأكبر سناً، أن بلير سيفسح المجال له. إلا أن استطلاعات الرأي سرعان ما أشارت إلى أن بلير يحظى بدعم أكبر بين الناخبين.[203] أصبحت علاقتهما في السلطة مضطربة للغاية لدرجة أنه قيل إن نائب رئيس الوزراء جون پرسكوت كان يضطر في كثير من الأحيان إلى العمل "كمستشار إرشاد زواج".[204]

أثناء الحملة الانتخابية 2010، أيد بلير علناً زعامة براون، وأشاد بالطريقة التي تعامل بها مع الأزمة المالية.[205]

Post-premiership (2007–present)

Diplomacy

On 27 June 2007, Blair officially resigned as prime minister after ten years in office, and he was officially confirmed as Middle East envoy for the United Nations, European Union, United States, and Russia.[206] Blair originally indicated that he would retain his parliamentary seat after his resignation as prime minister came into effect; however, on being confirmed for the Middle East role he resigned from the Commons by taking up an office of profit.[115] President George W. Bush had preliminary talks with Blair to ask him to take up the envoy role. White House sources stated that "both Israel and the Palestinians had signed up to the proposal".[207][208] In May 2008 Blair announced a new plan for peace and for Palestinian rights, based heavily on the ideas of the Peace Valley plan.[209] Blair resigned as envoy in May 2015.[210]

In 2025, according to a report in The Wall Street Journal, the Donald Trump administration is considering a plan to appoint Blair as the "Interim Gaza Administrator" within the framework of an entity called the "International Gaza Transition Organization."[211]

Private sector

In January 2008, it was confirmed that Blair would be joining investment bank JPMorgan Chase in a "senior advisory capacity"[212] and that he would advise Zurich Financial Services on climate change. His salary for this work is unknown, although it has been claimed it may be in excess of £500,000 per year.[212] Blair also gives lectures, earning up to US$250,000 for a 90-minute speech, and in 2008 he was said to be the highest paid speaker in the world.[213]

Blair taught a course on issues of faith and globalisation at the Yale University Schools of Management and Divinity as a Howland distinguished fellow during the 2008–09 academic year. In July 2009, this accomplishment was followed by the launching of the Faith and Globalisation Initiative with Yale University in the US, Durham University in the UK, and the National University of Singapore in Asia, to deliver a postgraduate programme in partnership with the Foundation.[214][215]

Blair's links with, and receipt of an undisclosed sum from, UI Energy Corporation, have also been subject to media comment in the UK.[216]

In July 2010 it was reported that his personal security guards claimed £250,000 a year in expenses from the taxpayer. Foreign Secretary William Hague said; "we have to make sure that [Blair's security] is as cost-effective as possible, that it doesn't cost any more to the taxpayer than is absolutely necessary".[217]

Tony Blair Associates

Blair established Tony Blair Associates to "allow him to provide, in partnership with others, strategic advice on a commercial and pro bono basis, on political and economic trends and governmental reform".[218] The profits from the firm go towards supporting Blair's "work on faith, Africa and climate change".[219]

Blair has been subject to criticism for potential conflicts of interest between his diplomatic role as a Middle East envoy, and his work with Tony Blair Associates,[220][221][222] and a number of prominent critics have even called for him to be sacked.[223] Blair has used his Quartet Tony Blair Associates works with the Kazakhstan government, advising the regime on judicial, economic and political reforms, but has been subject to criticism after accusations of "whitewashing" the image and human rights record of the regime.[224]

Blair responded to such criticism by saying his choice to advise the country is an example of how he can "nudge controversial figures on a progressive path of reform", and has stated that he receives no personal profit from this advisory role.[225] The Kazakhstan foreign minister said that the country was "honoured and privileged" to be receiving advice from Blair.[226][227] A letter obtained by The Daily Telegraph in August 2014 revealed Blair had given damage-limitation advice to Nursultan Nazarbayev after the December 2011 Zhanaozen massacre.[228] Blair was reported to have accepted a business advisory role with President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt, a situation deemed incompatible with his role as Middle East envoy. Blair described the report as "nonsense".[229][230]

Charity and non-profits

In November 2007 Blair launched the Tony Blair Sports Foundation, which aims to "increase childhood participation in sports activities, especially in the North East of England, where a larger proportion of children are socially excluded, and to promote overall health and prevent childhood obesity."[231] On 30 May 2008, Blair launched the Tony Blair Faith Foundation as a vehicle for encouraging different faiths to join in promoting respect and understanding, as well as working to tackle poverty. Reflecting Blair's own faith but not dedicated to any particular religion, the Foundation aims to "show how faith is a powerful force for good in the modern world". "The Foundation will use its profile and resources to encourage people of faith to work together more closely to tackle global poverty and conflict", says its mission statement.[232]

In February 2009 he applied to set up a charity called the Tony Blair Africa Governance Initiative: the application was approved in November 2009.[233] Blair's foundation hit controversy in October 2012, when news emerged that it was taking on unpaid interns.[234]

In December 2016, Blair created the Tony Blair Institute to promote global outlooks by governments and organisations.[235][236] In September 2023 former Finnish prime minister Sanna Marin joined him as a strategic adviser on political leaders' reform programmes in the institute.[237]

Books

A Journey

In March 2010, it was reported that Blair's memoirs, titled The Journey, would be published in September 2010.[238][239] In July 2010 it was announced the memoirs would be retitled A Journey.[240] The memoirs were seen by many as controversial and a further attempt to profit from his office and from acts related to overseas wars that were widely seen as wrong,[241][242][243] leading to anger and suspicion prior to launch.[242]

On 16 August 2010 it was announced that Blair would give the £4.6 million advance and all royalties from his memoirs to the Royal British Legion – the charity's largest ever single donation.[241][244]

Media analysis of the sudden announcement was wide-ranging, describing it as an act of "desperation" to obtain a better launch reception of a humiliating "publishing flop"[245] that had languished in the ratings,[241][245] "blood money" for the lives lost in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars,[241][243] an act with a "hidden motive" or an expression of "guilt",[241][242] a "genius move" to address the problem that "Tony Blair ha[d] one of the most toxic brands around" from a PR perspective, and a "cynical stunt to wipe the slate", but also as an attempt to make amends.[245] Friends had said that the act was partly motivated by the wish to "repair his reputation".[241]

The book was published on 1 September and within hours of its launch had become the fastest-selling autobiography of all time.[246] On 3 September Blair gave his first live interview since publication on The Late Late Show in Ireland, with protesters lying in wait there for him.[247] On 4 September, Blair was confronted by 200 anti-war and hardline Irish nationalist demonstrators before the first book signing of his memoirs at Eason's bookstore on O'Connell Street in Dublin, with angry activists chanting "war criminal" and that he had "blood on his hands", and clashing with Irish Police (Garda Síochána) as they tried to break through a security cordon outside the Eason's store. Blair was pelted with eggs and shoes, and encountered an attempted citizen's arrest for war crimes.[248]

On Leadership

Published in 2024, and described by George Osborne as "the most practically useful guide to politics I have ever read."[249]

Accusations of war crimes

Since the Iraq War, Blair has been the subject of war crimes accusations. Critics of his actions, including Bishop Desmond Tutu,[250] Harold Pinter[251] and Arundhati Roy[252] have called for his trial at the International Criminal Court.

In November 2011, a war crimes tribunal of the Kuala Lumpur War Crimes Commission, established by Malaysia's former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad, reached a unanimous conclusion that Blair was guilty of crimes against peace, as a result of his role in the Iraq War.[253] The proceedings lasted for four days, and consisted of five judges of judicial and academic backgrounds, a tribunal-appointed defence team in lieu of the defendants or representatives, and a prosecution team including international law professor Francis Boyle.[254]

In September 2012, Desmond Tutu suggested that Blair should follow the path of former African leaders who had been brought before the International Criminal Court in The Hague.[250] The human rights lawyer Geoffrey Bindman concurred with Tutu's suggestion that there should be a war crimes trial.[255] In a statement made in response to Tutu's comments, Blair defended his actions.[250] He was supported by Lord Falconer, who stated that the war had been authorised by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1441.[255]

In July 2017, former Iraqi general Abdulwaheed al-Rabbat launched a private war crimes prosecution in the High Court in London, asking for Blair, former foreign secretary Jack Straw and former attorney general Lord Goldsmith to be prosecuted for "the crime of aggression" for their role in the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The High Court ruled that, although the crime of aggression was recognised in international law, it was not an offence under UK law, and therefore the prosecution could not proceed.[256][257][258][259]

Blair defended

Some, such as John Rentoul, John McTernan, Geoffrey Robertson and Iain Dale, have countered accusations that Blair committed war crimes during his premiership, often highlighting how no case against Blair has ever made it to trial, suggesting that Blair broke no laws.[260][261][262][بحاجة لمصدر غير رئيسي]

Blair himself has defended his involvement in the Iraq War by highlighting the findings of the Iraq Survey Group, which found that Saddam had attempted to get sanctions lifted by undermining them, which would have enabled him to restart his WMD program.[263]

Political interventions and views

Response to the Iraq Inquiry

The Chilcot report issued after the conclusion of the Iraq Inquiry was published on 6 July 2016; it criticised Blair for joining the US in the war in Iraq in 2003. Afterward, Blair issued a statement and held a two-hour press conference to apologise, to justify the decisions he had made in 2003 "in good faith" and to deny allegations that the war had led to a significant increase in terrorism.[264] He acknowledged that the report made "real and material criticisms of preparation, planning, process and of the relationship with the United States" but cited sections of the report that he said "should lay to rest allegations of bad faith, lies or deceit". He stated: "whether people agree or disagree with my decision to take military action against Saddam Hussein; I took it in good faith and in what I believed to be the best interests of the country. ... I will take full responsibility for any mistakes without exception or excuse. I will at the same time say why, nonetheless, I believe that it was better to remove Saddam Hussein and why I do not believe this is the cause of the terrorism we see today whether in the Middle East or elsewhere in the world".[265][266]

Iran–West tensions

In an op-ed published by The Washington Post on 8 February 2019, Blair said: "Where Iran is exercising military interference, it should be strongly pushed back. Where it is seeking influence, it should be countered. Where its proxies operate, it should be held responsible. Where its networks exist, they should be disrupted. Where its leaders are saying what is unacceptable, they should be exposed. Where the Iranian people — highly educated and connected, despite their government — are protesting for freedom, they should be supported."[267] The Tony Blair Institute for Global Change warned of a growing Iranian threat.[268] The Tony Blair Institute confirmed that it has received donations from the U.S. State Department and Saudi Arabia.[269][270]

European Union

Blair did not want the UK to leave the EU and called for a referendum on the Brexit withdrawal agreement. Blair also maintained that once the terms deciding how the UK leaves the EU were known, the people should be able to vote again on those terms. Blair stated, "We know the options for Brexit. Parliament will have to decide on one of them. If Parliament can't then it should decide to go back to the people."[271]

However, after the 2019 general election in which the pro-withdrawal Conservative party won a sizeable majority of seats, Blair argued that remain supporters should "face up to one simple point: we lost" and "pivot to a completely new position...We're going to have to be constructive about it and see how Britain develops a constructive relationship with Europe and finds its new niche in the world."[272]

American power

Blair was interviewed in June 2020 for an article in the American magazine The Atlantic on European views of U.S. foreign policy concerning the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting recession, the rise of China, and the George Floyd protests. He affirmed his belief in the continued strength of American soft power and the need to address Iranian military aggression, European military underinvestment, and illicit Chinese trade practices. He said, however, "I think it's fair to say a lot of political leaders in Europe are dismayed by what they see as the isolationism growing in America and the seeming indifference to alliances. But I think there will come a time when America decides in its own interest to reengage, so I'm optimistic that America will in the end understand that this is not about relegating your self-interest behind the common interest; it's an understanding that by acting collectively in alliance with others you promote your own interests." Blair warned that structural issues plaguing American domestic policy needed to be addressed imminently.[273]

In August 2021, Blair criticised the withdrawal of U.S. and NATO troops from Afghanistan, saying that it was "in obedience to an imbecilic slogan about ending 'the forever wars'". Blair admitted mistakes in the management of the war but warned that "the reaction to our mistakes has been, unfortunately, further mistakes".[274]

Labour Party

Jeremy Corbyn

Blair was a critic of Jeremy Corbyn's leadership of the Labour Party, seeing it as too left-wing. He wrote in an opinion piece for The Guardian during the party's 2015 leadership election that if the party elected Corbyn, it would face a "rout, possibly annihilation" at the next election.[275] After the 2019 general election, Blair accused Corbyn of turning the party into a "glorified protest movement" and in a May 2021 New Statesman article, Blair suggested that the party needed to undergo a programme of "total deconstruction and reconstruction" and also said the party needed to shift to the centre on social issues in order to survive.[276] Blair touched on controversial topics such as transgender rights, the Black Lives Matter movement and climate change.[277][278][279]

Keir Starmer

Keir Starmer's leadership of the party has been widely compared to Blair's leadership and New Labour, having taken the party rightward to gain electability. Initially saying in 2021 that Starmer lacked a compelling message, Blair has since reacted more positively towards Starmer's leadership of the party, telling him he's "done a great job" in reforming the party during a Tony Blair Institute for Global Change's Future of Britain conference in 2023.[280] Blair's continued influence on the party, and on Starmer led him to be ranked sixteenth in the New Statesman's Left Power List 2023, described by the paper as electorally an "incomparable authority on how to win".[281] After Labour won the 2024 general election and Starmer became prime minister, Blair congratulated him on his victory, saying Starmer was "determined and ruthlessly effective" and appointed "exceptional talent to conduct the change and put the most capable frontbenchers in the most important positions for future government." He also offered Starmer advice, recommending he controls immigration amid the rise of the Reform UK party led by Nigel Farage, saying that the party poses a threat to Labour and not just the Conservatives.[282]

Personal life

Family

Blair married Cherie Booth on 29 March 1980.[283] They have four children: Euan, Nicky, Kathryn, and Leo.[284] Leo was the first legitimate child born to a serving prime minister in over 150 years – since Francis Russell was born to Lord John Russell on 11 July 1849.[285] All four children have Irish passports, by virtue of Blair's mother, Hazel Elizabeth Rosaleen Corscadden (12 June 1923 – 28 June 1975).[286] The family's primary residence is in Connaught Square; the Blairs own eight residences in total.[287] His first grandchild, a girl, was born in October 2016.[288]

Wealth

Blair's financial assets are structured in an opaque manner, and estimates of their extent vary widely.[289] These include figures of up to £100 million. Blair stated in 2014 that he was worth "less than £20 million".[290] A 2015 assertion, by Francis Beckett, David Hencke and Nick Kochan, concluded that Blair had acquired $90 million and a property portfolio worth $37.5 million in the eight years since he had left office.[291]

In October 2021, Blair was named in the Pandora Papers.[292]

Religious faith

In 2006, Blair referred to the role of his Christian faith in his decision to go to war in Iraq, stating that he had prayed about the issue, and saying that God would judge him for his decision: "I think if you have faith about these things, you realise that judgement is made by other people ... and if you believe in God, it's made by God as well."[293]

According to Press Secretary Alastair Campbell's diary, Blair often read the Bible before taking any important decisions. He states that Blair had a "wobble" and considered changing his mind on the eve of the bombing of Iraq in 1998.[294]

A longer exploration of his faith can be found in an interview with Third Way Magazine. There he says that "I was brought up as [a Christian], but I was not in any real sense a practising one until I went to Oxford. There was an Australian priest at the same college as me who got me interested again. In a sense, it was a rediscovery of religion as something living, that was about the world around me rather than some sort of special one-to-one relationship with a remote Being on high. Suddenly I began to see its social relevance. I began to make sense of the world".[295]

At one point Alastair Campbell intervened in an interview, preventing Blair from answering a question about his Christianity, explaining, "We don't do God."[296] Campbell later said that he had intervened only to end the interview because the journalist had been taking an excessive time, and that the comment had just been a throwaway line.[297]

Cherie Blair's friend and "spiritual guru" Carole Caplin is credited with introducing her and her husband to various New Age symbols and beliefs, including "magic pendants" known as "BioElectric Shields".[298] The most controversial of the Blairs' New Age practices occurred when on holiday in Mexico. The couple, wearing only bathing costumes, took part in a rebirthing procedure, which involved smearing mud and fruit over each other's bodies while sitting in a steam bath.[299]

In 1996, Blair, then an Anglican, was reprimanded by Cardinal Basil Hume for receiving Holy Communion while attending Mass at Cherie Blair's Catholic church, in contravention of canon law.[300] On 22 December 2007, it was disclosed that Blair had joined the Catholic Church. The move was described as "a private matter".[301][302] He had informed Pope Benedict XVI on 23 June 2007 — four days before he stepped down as Prime Minister — that he wanted to become a Catholic. The Pope and his advisors criticised some of Blair's political actions, but followed up with a reportedly unprecedented red carpet welcome, which included the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, Cormac Murphy-O'Connor, who would be responsible for Blair's Catholic instruction.[303] In 2009, Blair questioned the Pope's attitude towards homosexuality, arguing that religious leaders must start "rethinking" the issue.[304] In 2010, The Tablet named him as one of Britain's most influential Catholics.[305]

Honours

- United Kingdom: Privy Counsellor (1994)[58]

- United States: Congressional Gold Medal (2003)

- United Kingdom: Honorary Doctor of Law (LLD) from Queen's University Belfast (2008)

- United States:

Presidential Medal of Freedom (2009)

Presidential Medal of Freedom (2009) - Dan David Prize (2009)

- United States:

Liberty Medal (2010)

Liberty Medal (2010) - Kosovo:

Order of Freedom (2010)

Order of Freedom (2010) - United Kingdom:

Knight Companion of the Most Noble Order of the Garter (2022)

Knight Companion of the Most Noble Order of the Garter (2022)

In May 2007, Blair was invested as a paramount chief by the chiefs and people of the village of Mahera in Sierra Leone. The honour was bestowed upon him in recognition of the role played by his government in the Sierra Leone Civil War.[306]

On 22 May 2008, Blair received an honorary law doctorate from Queen's University Belfast, alongside Bertie Ahern, for distinction in public service and roles in the Northern Ireland peace process.[307]

On 13 January 2009, Blair was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush.[308] Bush stated that Blair was given the award "in recognition of exemplary achievement and to convey the utmost esteem of the American people"[309] and cited Blair's support for the War on Terror and his role in achieving peace in Northern Ireland as two reasons for justifying his being presented with the award.[310]

On 16 February 2009, Blair was awarded the Dan David Prize by Tel Aviv University for "exceptional leadership and steadfast determination in helping to engineer agreements and forge lasting solutions to areas in conflict". He was awarded the prize in May 2009.[311][312][313]

On 8 July 2010, Blair was awarded the Order of Freedom by President Fatmir Sejdiu of Kosovo.[314] As Blair is considered to have been instrumental in ending the conflict in Kosovo, some boys born in the country following the war have been given the name Toni or Tonibler.[315][316]

On 13 September 2010, Blair was awarded the Liberty Medal at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[317] It was presented by former president Bill Clinton, and is awarded annually to "men and women of courage and conviction who strive to secure the blessings of liberty to people around the globe".[317][318]

On 31 December 2021, it was announced that Queen Elizabeth II had appointed Blair a Knight Companion of the Order of the Garter (KG).[319][320] Blair had reportedly indicated when he left office that he did not want the traditional knighthood or peerage bestowed on former prime ministers.[321] A petition cited his role in the Iraq War as a reason to remove the knighthood and garnered more than one million signatures.[322] He received his Garter insignia on 10 June 2022 from the Queen during an audience at Windsor Castle.[323]

Works

- Blair, Tony (2024). On Leadership: Lessons for the 21st Century. London: Hutchinson Heinemann. ISBN 9781529151510.

- Blair, Tony (2010). A Journey. London: Random House. ISBN 0-09-192555-X. OCLC 657172683.

- Blair, Tony (2002). The Courage of Our Convictions. London: Fabian Society. ISBN 0-7163-0603-4.

- Blair, Tony (2000). Superpower: Not Superstate? (Federal Trust European Essays). London: Federal Trust for Education & Research. ISBN 1-903403-25-1.

- Blair, Tony (1998). The Third Way: New Politics for the New Century. London: Fabian Society. ISBN 0-7163-0588-7.

- Blair, Tony (1998). Leading the Way: New Vision for Local Government. London: Institute for Public Policy Research. ISBN 1-86030-075-8.

- Blair, Tony (1997). New Britain: My Vision of a Young Country. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-8133-3338-5.

- Blair, Tony (1995). Let Us Face the Future. London: Fabian Society. ISBN 0-7163-0571-2.

- Blair, Tony (1994). What Price a Safe Society?. London: Fabian Society. ISBN 0-7163-0562-3.

- Blair, Tony (1994). Socialism. London: Fabian Society. ISBN 0-7163-0565-8.

See also

- Blatcherism

- Bush–Blair 2003 Iraq memo

- Cash-for-Honours scandal

- Cultural depictions of Tony Blair

- Parliamentary motion to impeach Tony Blair

- Halsbury's Laws of England (2004), reference to impeachment in volume on Constitutional Law and Human Rights, paragraph 416

- Taking Liberties (film)

Notes and references

Notes

References

- ^ Seldon, Anthony (10 August 2015). "Why is Tony Blair so unpopular?". BBC News (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). Archived from the original on 15 May 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ "Tony Blair: a controversial knight". The Week. 7 January 2022. Archived from the original on 15 May 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick (20 March 2023). "How Iraq war destroyed UK's trust in politicians and left Labour in turmoil". The Guardian (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 15 May 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ Farand, Chloe (1 August 2017). "A huge number of Britons want to see Tony Blair tried for Iraq war crimes". The Independent. Archived from the original on 15 May 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ أ ب "Blair's birthplace is bulldozed in Edinburgh". Edinburgh Evening News. Johnston Press. 9 August 2006. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 18 November 2006.

- ^ قالب:Who's Who

- ^ "Tony Blair profile". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ "Blair's birthplace is bulldozed in Edinburgh". The Scotsman. 9 August 2006. Archived from the original on 9 May 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "Leo Blair". The Telegraph. 18 November 2012. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ "Blair: 'Why adoption is close to my heart'". The Guardian. 21 December 2000. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017.

- ^ "Local Map". Ballyshannon Town Council. Archived from the original on 21 November 2009. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

Lipsett's Grocery Shop: This is the birthplace of Hazel (Corscadden) Blair, mother of British Prime Minister Tony Blair. Her mother's maiden name was Lipsett and Hazel was born over the shop.

- ^ Watt, Nicholas; Bowcott, Owen (14 March 2007). "We had no file on him but it was clear he was up for the business". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

In the second part of our series on the peace process, Sinn Féin chief negotiator Martin McGuinness recalls his first encounter with the PM and explains how he saved the Good Friday deal

- ^ أ ب Langdon, Julia (17 November 2012). "Leo Blair obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Ahmed, Kamal (27 April 2003). "Tony's big adventure". The Observer. London. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2006.

- ^ Waugh, Chris (20 September 2018). "Newcastle fan Tony Blair shock candidate for key Premier League role". Chronicle Live. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ Marriage, Madison (29 June 2010). "British Prime Ministers and their passion for football". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ "Blair football 'myth' cleared up". BBC. 26 November 2008. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ "Alumni Roll Call". Durham Chorister School website. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- ^ أ ب Ed Black's diary (23 July 2004). "Tony Blair's revolting schooldays". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 27 March 2008. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- ^ Rentoul 2001, pp. 15–17

- ^ Rentoul 2001, p. 21

- ^ Rentoul 2001, pp. 28–31

- ^ Michaelmas Term 1974. Complete Alphabetical List of the Resident Members of the University of Oxford. Oxford University Press. 1974. p. 10.

- ^ Rentoul 2001, pp. 37–38

- ^ Huntley, John (1990). Mark Ellen talks about Tony Blair in Ugly Rumours. Film 90788 (YouTube video). HuntleyFilmArchives. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ Wiegand, Chris (27 November 2015). "Tony Blair recalls 'dire' standup attempts and his role as 'Captain Kink'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ^ Merrick, Rob (10 August 2017). "Tony Blair reveals he was a student 'Trot' inspired to enter politics by the life of Bolshevik leader Leon Trotsky". The Independent. UK. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

I suddenly thought the world's full of these extraordinary causes and injustices and here's this this guy Trotsky who was so inspired by all of this that he went out to create a Russian revolution and change the world. It was like a light going on.

- ^ Asthana, Anushka (10 August 2017). "Blair reveals he 'toyed with Marxism' after reading book on Trotsky". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ Nimmo, Joe (5 October 2016). "Why have so many PMs gone to Oxford?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ "British Prime Ministers". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 19 November 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ Ahmed, Kamal (27 April 2003). "Family tragedy at the heart of Blair's ambition". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ McGreevy, Ronan (2 September 2010). "Mother described as an 'almost saintly woman'". Irish Times. Archived from the original on 4 May 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ "Law school to merge with City". Times Higher Education. 24 August 2001. Retrieved 17 February 2025.

- ^ Segell, Glen (2001). Electronic Democracy and the UK 2001 Elections. Glen Segell Publishers. ISBN 978-1-901414-23-3. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ (Rentoul 1996, p. 101)

- ^ "Labour's Old Romantic: A Film Portrait of Michael Foot" Archived 17 فبراير 2016 at the Wayback Machine, BBC Two, Friday 5 March 2010 . Portion available here [1] Archived 4 ديسمبر 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Russell, William (28 May 1982). "By-election boost for Thatcher's stance". The Glasgow Herald. p. 1. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ أ ب ت Blair, Tony (July 1982). "The full text of Tony Blair's letter to Michael Foot written in July 1982". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2006.

- ^ أ ب (Marquand 2010, p. 197)

- ^ (Rentoul 1996, p. 109)

- ^ (Rentoul 1996, p. 115)

- ^ "Labour's Election Who's Who", Labour Party, 1983, Appendix p. 2.

- ^ "Blair's agent suspended over foul-mouthed threat". The Guardian. Press Association. 10 October 2007. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ "1983 Election Leaflet for Tony Blair". George Ferguson. 9 June 1983. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Coleman, Vernon (2006). The Truth They Won't Tell You (And Don't Want You To Know) About The EU. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ "1975: Labour votes to leave the EEC". BBC News. Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ Johnston, Philip (26 April 2004). "Home front". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ Seldon, Anthony (4 September 2008). Blair Unbound. Simon & Schuster. p. 454. ISBN 978-1-84739-499-6. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ Seddon, Mark (2004). "America's Friend: Reflections on Tony Blair". Logos 3.4. Archived from the original on 18 November 2006. Retrieved 18 November 2006.

- ^ Langdon, Julia (8 November 1984). "Shadow team gets infusion of new blood". The Guardian. p. 2.

- ^ Watt, Nicholas (30 April 2007). "'He's a bastard but he's our bastard'". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ "BBC Archive". BBC Programme Catalogue. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ Jeffreys 1999, p. 216

- ^ Carvel, John (9 July 1987). "A fresh team of 'Yaks' will take on Labour's burden". The Guardian. p. 2.

- ^ (Rentoul 2001, pp. 206–18)

- ^ (Rentoul 2001, pp. 249–66)

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Timeline: The Blair Years". BBC News. 10 May 2007. Archived from the original on 27 March 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ أ ب Leigh, Rayment. "Privy Counsellors 1969–present". Archived from the original on 7 June 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ White, Michael (6 June 2003). "The guarantee which came to dominate new Labour politics for a decade". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ Mayer, Catherine (16 January 2005). "Fight Club". Time. Archived from the original on 27 January 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ Brown, Colin; d'Ancona, Matthew. "The night that power was on the menu". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ Wheeler, Brian (10 May 2007). "The Tony Blair story". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ "Leader's speech, Blackpool 1994". British Political Speech. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ White, Michael (5 October 1994). "Blair defines the new Labour". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 July 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ أ ب Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York City: Basic Books. p. 326. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

- ^ Peter Barberis; John McHugh; Mike Tyldesley (2000). Encyclopedia of British and Irish Political Organizations: Parties, Groups and Movements of the 20th Century. A&C Black. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-8264-5814-8. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "About Labour". The Labour Party. 2006. Archived from the original on 16 November 2006. Retrieved 18 November 2006.

- ^ Blair, Tony (1995). "2: Labour Past, Present and Future". Let Us Face the Future. Fabian Pamphlets. Vol. 571. Fabian Society. p. 2. ISBN 0-7163-0571-2. ISSN 0307-7523. Retrieved 3 January 2016 – via LSE Digital Library.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ignored ISSN errors (link) - ^ Gani, Aisha (9 August 2015). "Clause IV: a brief history". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ أ ب "1997: Labour landslide ends Tory rule". BBC News. 15 April 2005. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ Coughlan, Sean (14 May 2007). "Education, education, education". BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 May 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ See Maastricht Rebels

- ^ Early, Chas (2 May 2015). "May 2, 1997: Labour win general election by a landslide to end 18 years of Conservative rule". BT News. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

The Labour Party won its greatest-ever number of seats in a landslide general election victory on this day in 1997, ending 18 years of Conservative rule... In their worst election defeat since 1906, the Conservatives retained just 165 MPs, with their smallest share of the vote since 1832 under the Duke of Wellington.

- ^ All Guardian/ICM poll results Archived 14 فبراير 2016 at the Wayback Machine (Google Docs). Via this Archived 12 مارس 2017 at the Wayback Machine article.

- ^ "Biography: The Prime Minister Tony Charles Lynton Blair". Prime Minister's Office. Archived from the original on 4 June 2007. Retrieved 18 November 2006.

- ^ "Blair Labour's longest-serving PM". BBC News. 6 February 2005. Archived from the original on 10 September 2007. Retrieved 7 February 2024.

- ^ Rawnsley, Andrew (30 April 2017). "Tony Blair: 'Labour can win at any point that it wants to get back to winning ways'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

... made possible only by his unique feat of winning three back-to-back terms for his party

- ^ "1998: Northern Ireland peace deal reached". BBC News Archive. 10 April 1998. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008.

- ^ Stephens, Philip (10 May 2007). "Blair's remarkable record". Financial Times.

- ^ "Omagh, Northern Ireland's worst atrocity". Telegraph.co.uk. 24 December 2007.

- ^ "Blair: The Inside Story". BBC. 22 February 2007. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007.

- ^ Andrew Marr, A History of Modern Britain (2008 printing), p. 550