جليد

| Ice | |

|---|---|

An ice block | |

| Physical properties | |

| الكثافة (ρ) | 0.9167[1]–0.9168[2] g/cm3 |

| Refractive index (n) | 1.309 |

| Mechanical properties | |

| معامل ينگ (E) | 3400 to 37,500 kg-force/cm3[2] |

| Tensile strength (σt) | 5 to 18 kg-force/cm2[2] |

| Compressive strength (σc) | 24 to 60 kg-force/cm2[2] |

| Poisson's ratio (ν) | 0.36±0.13[2] |

| Thermal properties | |

| Thermal conductivity (k) | 0.0053(1 + 0.0015 θ) cal/(cm s K), θ = temperature in °C[2] |

| Linear thermal expansion coefficient (α) | 5.5×10−5[2] |

| Specific heat capacity (c) | 0.5057 − 0.001863 θ cal/(g K), θ = absolute value of temperature in °C[2] |

| Electrical properties | |

| Dielectric constant (εr) | ~95[3] |

| The properties of ice vary substantially with temperature, purity and other factors. | |

الجليد Ice ، هو شكل ترسيبي يتكون من كتل من بلورات جليدية صغيرة. تنمو هذه البلورات معًا من بخار الماء في السحب الباردة. لتكون الندف الثلجية عند اصطدامها وتماسك بعضها ببعض. فهو الحالة الصلبة المتبلورة غير الفلزية لمادة قد تكون سائلة أو غازية في درجة حرارة الغرفة، ومن الأمثلة عليها الجليد المائي أو جليد الأمونيا. كما في اللغة الإنجليزية، كلمة جليد تعني غالبا جليدا مائيا.

Ice is water that is frozen into a solid state, typically forming at or below temperatures of 0 °C, 32 °F, or 273.15 K. It occurs naturally on Earth, on other planets, in Oort cloud objects, and as interstellar ice. As a naturally occurring crystalline inorganic solid with an ordered structure, ice is considered to be a mineral. Depending on the presence of impurities such as particles of soil or bubbles of air, it can appear transparent or a more or less opaque bluish-white color.

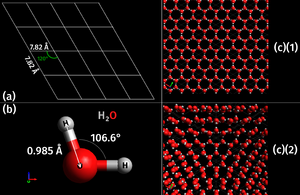

Virtually all of the ice on Earth is of a hexagonal crystalline structure denoted as ice Ih (spoken as "ice one h"). Depending on temperature and pressure, at least nineteen phases (packing geometries) can exist. The most common phase transition to ice Ih occurs when liquid water is cooled below 0 °C (273.15 K, 32 °F) at standard atmospheric pressure. When water is cooled rapidly (quenching), up to three types of amorphous ice can form. Interstellar ice is overwhelmingly low-density amorphous ice (LDA), which likely makes LDA ice the most abundant type in the universe. When cooled slowly, correlated proton tunneling occurs below −253.15 °C (20 K, −423.67 °F) giving rise to macroscopic quantum phenomena.

Ice is abundant on the Earth's surface, particularly in the polar regions and above the snow line, where it can aggregate from snow to form glaciers and ice sheets. As snowflakes and hail, ice is a common form of precipitation, and it may also be deposited directly by water vapor as frost. The transition from ice to water is melting and from ice directly to water vapor is sublimation. These processes plays a key role in Earth's water cycle and climate. In the recent decades, ice volume on Earth has been decreasing due to climate change. The largest declines have occurred in the Arctic and in the mountains located outside of the polar regions. The loss of grounded ice (as opposed to floating sea ice) is the primary contributor to sea level rise.

Humans have been using ice for various purposes for thousands of years. Some historic structures designed to hold ice to provide cooling are over 2,000 years old. Before the invention of refrigeration technology, the only way to safely store food without modifying it through preservatives was to use ice. Sufficiently solid surface ice makes waterways accessible to land transport during winter, and dedicated ice roads may be maintained. Ice also plays a major role in winter sports.

الخصائص الطبيعية

Ice possesses a regular crystalline structure based on the molecule of water, which consists of a single oxygen atom covalently bonded to two hydrogen atoms, or H–O–H. However, many of the physical properties of water and ice are controlled by the formation of hydrogen bonds between adjacent oxygen and hydrogen atoms; while it is a weak bond, it is nonetheless critical in controlling the structure of both water and ice.[6]

An unusual property of water is that its solid form—ice frozen at atmospheric pressure—is approximately 8.3% less dense than its liquid form; this is equivalent to a volumetric expansion of 9%. The density of ice is 0.9167[1]–0.9168[2] g/cm3 at 0 °C and standard atmospheric pressure (101,325 Pa), whereas water has a density of 0.9998[1]–0.999863[2] g/cm3 at the same temperature and pressure. Liquid water is densest, essentially 1.00 g/cm3, at 4 °C and begins to lose its density as the water molecules begin to form the hexagonal crystals of ice as the freezing point is reached. This is due to hydrogen bonding dominating the intermolecular forces, which results in a packing of molecules less compact in the solid. The density of ice increases slightly with decreasing temperature and has a value of 0.9340 g/cm3 at −180 °C (93 K).[7]

When water freezes, it increases in volume (about 9% for fresh water).[8] The effect of expansion during freezing can be dramatic, and ice expansion is a basic cause of freeze-thaw weathering of rock in nature and damage to building foundations and roadways from frost heaving. It is also a common cause of the flooding of houses when water pipes burst due to the pressure of expanding water when it freezes.[9]

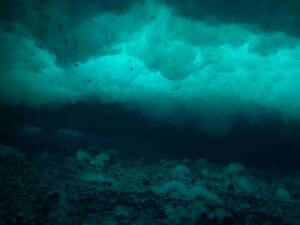

Because ice is less dense than liquid water, it floats, and this prevents bottom-up freezing of the bodies of water. Instead, a sheltered environment for animal and plant life is formed beneath the floating ice, which protects the underside from short-term weather extremes such as wind chill. Sufficiently thin floating ice allows light to pass through, supporting the photosynthesis of bacterial and algal colonies.[10] When sea water freezes, the ice is riddled with brine-filled channels which sustain sympagic organisms such as bacteria, algae, copepods and annelids. In turn, they provide food for animals such as krill and specialized fish like the bald notothen, fed upon in turn by larger animals such as emperor penguins and minke whales.[11]

When ice melts, it absorbs as much energy as it would take to heat an equivalent mass of water by 80 °C (176 °F).[12] During the melting process, the temperature remains constant at 0 °C (32 °F). While melting, any energy added breaks the hydrogen bonds between ice (water) molecules. Energy becomes available to increase the thermal energy (temperature) only after enough hydrogen bonds are broken that the ice can be considered liquid water. The amount of energy consumed in breaking hydrogen bonds in the transition from ice to water is known as the heat of fusion.[12][8]

As with water, ice absorbs light at the red end of the spectrum preferentially as the result of an overtone of an oxygen–hydrogen (O–H) bond stretch. Compared with water, this absorption is shifted toward slightly lower energies. Thus, ice appears blue, with a slightly greener tint than liquid water. Since absorption is cumulative, the color effect intensifies with increasing thickness or if internal reflections cause the light to take a longer path through the ice.[13] Other colors can appear in the presence of light absorbing impurities, where the impurity is dictating the color rather than the ice itself. For instance, icebergs containing impurities (e.g., sediments, algae, air bubbles) can appear brown, grey or green.[13]

Because ice in natural environments is usually close to its melting temperature, its hardness shows pronounced temperature variations. At its melting point, ice has a Mohs hardness of 2 or less, but the hardness increases to about 4 at a temperature of −44 °C (−47 °F) and to 6 at a temperature of −78.5 °C (−109.3 °F), the vaporization point of solid carbon dioxide (dry ice).[14]

الأطوار

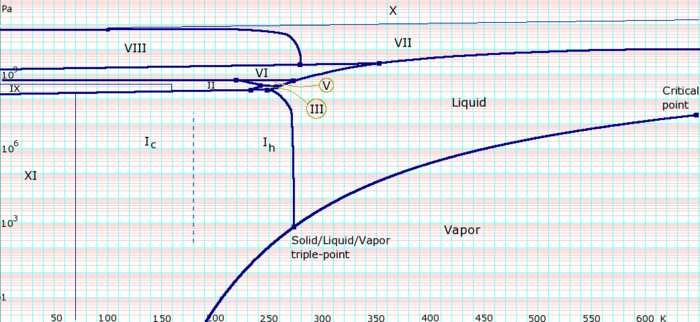

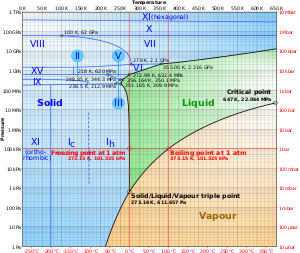

Most liquids under increased pressure freeze at higher temperatures because the pressure helps to hold the molecules together. However, the strong hydrogen bonds in water make it different: for some pressures higher than 1 atm (0.10 MPa), water freezes at a temperature below 0 °C (32 °F). Ice, water, and water vapour can coexist at the triple point, which is exactly 273.16 K (0.01 °C) at a pressure of 611.657 Pa.[16][17] The kelvin was defined as 1/273.16 of the difference between this triple point and absolute zero,[18] though this definition changed in May 2019.[19] Unlike most other solids, ice is difficult to superheat. In an experiment, ice at −3 °C was superheated to about 17 °C for about 250 picoseconds.[20]

Subjected to higher pressures and varying temperatures, ice can form in nineteen separate known crystalline phases at various densities, along with hypothetical proposed phases of ice that have not been observed.[21] With care, at least fifteen of these phases (one of the known exceptions being ice X) can be recovered at ambient pressure and low temperature in metastable form.[22][23] The types are differentiated by their crystalline structure, proton ordering,[24] and density. There are also two metastable phases of ice under pressure, both fully hydrogen-disordered; these are Ice IV and Ice XII. Ice XII was discovered in 1996. In 2006, Ice XIII and Ice XIV were discovered.[25] Ices XI, XIII, and XIV are hydrogen-ordered forms of ices Ih, V, and XII respectively. In 2009, ice XV was found at extremely high pressures and −143 °C.[26] At even higher pressures, ice is predicted to become a metal; this has been variously estimated to occur at 1.55 TPa[27] or 5.62 TPa.[28]

As well as crystalline forms, solid water can exist in amorphous states as amorphous solid water (ASW) of varying densities. In outer space, hexagonal crystalline ice is present in the ice volcanoes,[29] but is extremely rare otherwise. Even icy moons like Ganymede are expected to mainly consist of other crystalline forms of ice.[30][31] Water in the interstellar medium is dominated by amorphous ice, making it likely the most common form of water in the universe.[32] Low-density ASW (LDA), also known as hyperquenched glassy water, may be responsible for noctilucent clouds on Earth and is usually formed by deposition of water vapor in cold or vacuum conditions.[33] High-density ASW (HDA) is formed by compression of ordinary ice Ih or LDA at GPa pressures. Very-high-density ASW (VHDA) is HDA slightly warmed to 160 K under 1–2 GPa pressures.[34]

Ice from a theorized superionic water may possess two crystalline structures. At pressures in excess of 500،000 bar (7،300،000 psi) such superionic ice would take on a body-centered cubic structure. However, at pressures in excess of 1،000،000 bar (15،000،000 psi) the structure may shift to a more stable face-centered cubic lattice. It is speculated that superionic ice could compose the interior of ice giants such as Uranus and Neptune.[35]

خصائص الاحتكاك

Ice is "slippery" because it has a low coefficient of friction. This subject was first scientifically investigated in the 19th century. The preferred explanation at the time was "pressure melting" -i.e. the blade of an ice skate, upon exerting pressure on the ice, would melt a thin layer, providing sufficient lubrication for the blade to glide across the ice.[36] Yet, 1939 research by Frank P. Bowden and T. P. Hughes found that skaters would experience a lot more friction than they actually do if it were the only explanation. Further, the optimum temperature for figure skating is −5.5 °C (22 °F; 268 K) and −9 °C (16 °F; 264 K) for hockey; yet, according to pressure melting theory, skating below −4 °C (25 °F; 269 K) would be outright impossible.[37] Instead, Bowden and Hughes argued that heating and melting of the ice layer is caused by friction. However, this theory does not sufficiently explain why ice is slippery when standing still even at below-zero temperatures.[36]

Subsequent research suggested that ice molecules at the interface cannot properly bond with the molecules of the mass of ice beneath (and thus are free to move like molecules of liquid water). These molecules remain in a semi-liquid state, providing lubrication regardless of pressure against the ice exerted by any object. However, the significance of this hypothesis is disputed by experiments showing a high coefficient of friction for ice using atomic force microscopy.[37] Thus, the mechanism controlling the frictional properties of ice is still an active area of scientific study.[38] A comprehensive theory of ice friction must take into account all of the aforementioned mechanisms to estimate friction coefficient of ice against various materials as a function of temperature and sliding speed. 2014 research suggests that frictional heating is the most important process under most typical conditions.[39]

Natural formation

The term that collectively describes all of the parts of the Earth's surface where water is in frozen form is the cryosphere. Ice is an important component of the global climate, particularly in regard to the water cycle. Glaciers and snowpacks are an important storage mechanism for fresh water; over time, they may sublimate or melt. Snowmelt is an important source of seasonal fresh water.[42][43] The World Meteorological Organization defines several kinds of ice depending on origin, size, shape, influence and so on.[44] Clathrate hydrates are forms of ice that contain gas molecules trapped within its crystal lattice.[45][46]

In the oceans

Ice that is found at sea may be in the form of drift ice floating in the water, fast ice fixed to a shoreline or anchor ice if attached to the seafloor.[47] Ice which calves (breaks off) from an ice shelf or a coastal glacier may become an iceberg.[48] The aftermath of calving events produces a loose mixture of snow and ice known as Ice mélange.[49]

Sea ice forms in several stages. At first, small, millimeter-scale crystals accumulate on the water surface in what is known as frazil ice. As they become somewhat larger and more consistent in shape and cover, the water surface begins to look "oily" from above, so this stage is called grease ice.[50] Then, ice continues to clump together, and solidify into flat cohesive pieces known as ice floes. Ice floes are the basic building blocks of sea ice cover, and their horizontal size (defined as half of their diameter) varies dramatically, with the smallest measured in centimeters and the largest in hundreds of kilometers.[51] An area which is over 70% ice on its surface is said to be covered by pack ice.[52]

Fully formed sea ice can be forced together by currents and winds to form pressure ridges up to 12 متر (39 ft) tall.[53] On the other hand, active wave activity can reduce sea ice to small, regularly shaped pieces, known as pancake ice.[54] Sometimes, wind and wave activity "polishes" sea ice to perfectly spherical pieces known as ice eggs.[55][56]

Grease ice in the Bering Sea

A first-year sea ice ridge in the Central Arctic, photographed by the MOSAiC expedition on July 4, 2020

Anchor ice on the seafloor at McMurdo Sound, Antarctica.

On land

The largest ice formations on Earth are the two ice sheets which almost completely cover the world's largest island, Greenland, and the continent of Antarctica. These ice sheets have an average thickness of over 1 km (0.6 mi) and have existed for millions of years.[57][58]

Other major ice formations on land include ice caps, ice fields, ice streams and glaciers. In particular, the Hindu Kush region is known as the Earth's "Third Pole" due to the large number of glaciers it contains. They cover an area of around 80،000 km2 (31،000 sq mi), and have a combined volume of between 3,000-4,700 km3.[42] These glaciers are nicknamed "Asian water towers", because their meltwater run-off feeds into rivers which provide water for an estimated two billion people.[43]

Permafrost refers to soil or underwater sediment which continuously remains below 0 °C (32 °F) for two years or more.[59] The ice within permafrost is divided into four categories: pore ice, vein ice (also known as ice wedges), buried surface ice and intrasedimental ice (from the freezing of underground waters).[60] One example of ice formation in permafrost areas is aufeis - layered ice that forms in Arctic and subarctic stream valleys. Ice, frozen in the stream bed, blocks normal groundwater discharge, and causes the local water table to rise, resulting in water discharge on top of the frozen layer. This water then freezes, causing the water table to rise further and repeat the cycle. The result is a stratified ice deposit, often several meters thick.[61] Snow line and snow fields are two related concepts, in that snow fields accumulate on top of and ablate away to the equilibrium point (the snow line) in an ice deposit.[62]

On rivers and streams

Ice which forms on moving water tends to be less uniform and stable than ice which forms on calm water. Ice jams (sometimes called "ice dams"), when broken chunks of ice pile up, are the greatest ice hazard on rivers. Ice jams can cause flooding, damage structures in or near the river, and damage vessels on the river. Ice jams can cause some hydropower industrial facilities to completely shut down. An ice dam is a blockage from the movement of a glacier which may produce a proglacial lake. Heavy ice flows in rivers can also damage vessels and require the use of an icebreaker vessel to keep navigation possible.[63][64]

Ice discs are circular formations of ice floating on river water. They form within eddy currents, and their position results in asymmetric melting, which makes them continuously rotate at a low speed.[65][66]

On lakes

Ice forms on calm water from the shores, a thin layer spreading across the surface, and then downward. Ice on lakes is generally four types: primary, secondary, superimposed and agglomerate.[67][68] Primary ice forms first. Secondary ice forms below the primary ice in a direction parallel to the direction of the heat flow. Superimposed ice forms on top of the ice surface from rain or water which seeps up through cracks in the ice which often settles when loaded with snow. An ice shove occurs when ice movement, caused by ice expansion and/or wind action, occurs to the extent that ice pushes onto the shores of lakes, often displacing sediment that makes up the shoreline.[69]

Shelf ice is formed when floating pieces of ice are driven by the wind piling up on the windward shore. This kind of ice may contain large air pockets under a thin surface layer, which makes it particularly hazardous to walk across it.[70] Another dangerous form of rotten ice to traverse on foot is candle ice, which develops in columns perpendicular to the surface of a lake. Because it lacks a firm horizontal structure, a person who has fallen through has nothing to hold onto to pull themselves out.[71]

As precipitation

Snow and freezing rain

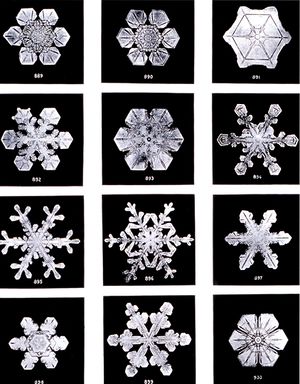

Snow crystals form when tiny supercooled cloud droplets (about 10 μm in diameter) freeze. These droplets are able to remain liquid at temperatures lower than −18 °C (255 K; 0 °F), because to freeze, a few molecules in the droplet need to get together by chance to form an arrangement similar to that in an ice lattice; then the droplet freezes around this "nucleus". Experiments show that this "homogeneous" nucleation of cloud droplets only occurs at temperatures lower than −35 °C (238 K; −31 °F).[72] In warmer clouds an aerosol particle or "ice nucleus" must be present in (or in contact with) the droplet to act as a nucleus. Our understanding of what particles make efficient ice nuclei is poor – what we do know is they are very rare compared to that cloud condensation nuclei on which liquid droplets form. Clays, desert dust and biological particles may be effective,[73] although to what extent is unclear. Artificial nuclei are used in cloud seeding.[74] The droplet then grows by condensation of water vapor onto the ice surfaces.[75]

Ice storm is a type of winter storm characterized by freezing rain, which produces a glaze of ice on surfaces, including roads and power lines. In the United States, a quarter of winter weather events produce glaze ice, and utilities need to be prepared to minimize damages.[76]

Hard forms

Hail forms in storm clouds when supercooled water droplets freeze on contact with condensation nuclei, such as dust or dirt. The storm's updraft blows the hailstones to the upper part of the cloud. The updraft dissipates and the hailstones fall down, back into the updraft, and are lifted up again. Hail has a diameter of 5 ميليمتر (0.20 in) or more.[77] Within METAR code, GR is used to indicate larger hail, of a diameter of at least 6.4 ميليمتر (0.25 in) and GS for smaller.[78] Stones of 19 ميليمتر (0.75 in), 25 ميليمتر (1.0 in) and 44 ميليمتر (1.75 in) are the most frequently reported hail sizes in North America.[79] Hailstones can grow to 15 سنتيمتر (6 in) and weigh more than 0.5 كيلوغرام (1.1 lb).[80] In large hailstones, latent heat released by further freezing may melt the outer shell of the hailstone. The hailstone then may undergo 'wet growth', where the liquid outer shell collects other smaller hailstones.[81] The hailstone gains an ice layer and grows increasingly larger with each ascent. Once a hailstone becomes too heavy to be supported by the storm's updraft, it falls from the cloud.[82]

Hail forms in strong thunderstorm clouds, particularly those with intense updrafts, high liquid water content, great vertical extent, large water droplets, and where a good portion of the cloud layer is below freezing 0 °C (32 °F).[77] Hail-producing clouds are often identifiable by their green coloration.[83][84] The growth rate is maximized at about −13 °C (9 °F), and becomes vanishingly small much below −30 °C (−22 °F) as supercooled water droplets become rare. For this reason, hail is most common within continental interiors of the mid-latitudes, as hail formation is considerably more likely when the freezing level is below the altitude of 11،000 أقدام (3،400 m).[85] Entrainment of dry air into strong thunderstorms over continents can increase the frequency of hail by promoting evaporative cooling which lowers the freezing level of thunderstorm clouds giving hail a larger volume to grow in. Accordingly, hail is actually less common in the tropics despite a much higher frequency of thunderstorms than in the mid-latitudes because the atmosphere over the tropics tends to be warmer over a much greater depth. Hail in the tropics occurs mainly at higher elevations.[86]

Ice pellets (METAR code PL[78]) are a form of precipitation consisting of small, translucent balls of ice, which are usually smaller than hailstones.[87] This form of precipitation is also referred to as "sleet" by the United States National Weather Service.[88] (In British English "sleet" refers to a mixture of rain and snow.) Ice pellets typically form alongside freezing rain, when a wet warm front ends up between colder and drier atmospheric layers. There, raindrops would both freeze and shrink in size due to evaporative cooling.[89] So-called snow pellets, or graupel, form when multiple water droplets freeze onto snowflakes until a soft ball-like shape is formed.[90] So-called "diamond dust", (METAR code IC[78]) also known as ice needles or ice crystals, forms at temperatures approaching −40 °C (−40 °F) due to air with slightly higher moisture from aloft mixing with colder, surface-based air.[91]

On surfaces

As water drips and re-freezes, it can form hanging icicles, or stalagmite-like structures on the ground.[92] On sloped roofs, buildup of ice can produce an ice dam, which stops melt water from draining properly and potentially leads to damaging leaks.[93] More generally, water vapor depositing onto surfaces due to high relative humidity and then freezing results in various forms of atmospheric icing, or frost. Inside buildings, this can be seen as ice on the surface of un-insulated windows.[94] Hoar frost is common in the environment, particularly in the low-lying areas such as valleys.[95] In Antarctica, the temperatures can be so low that electrostatic attraction is increased to the point hoarfrost on snow sticks together when blown by wind into tumbleweed-like balls known as yukimarimo.[96]

Sometimes, drops of water crystallize on cold objects as rime instead of glaze. Soft rime has a density between a quarter and two thirds that of pure ice,[97] due to a high proportion of trapped air, which also makes soft rime appear white. Hard rime is denser, more transparent, and more likely to appear on ships and aircraft.[98][99] Cold wind specifically causes what is known as advection frost when it collides with objects. When it occurs on plants, it often causes damage to them.[100] Various methods exist to protect agricultural crops from frost - from simply covering them to using wind machines.[101][102] In recent decades, irrigation sprinklers have been calibrated to spray just enough water to preemptively create a layer of ice that would form slowly and so avoid a sudden temperature shock to the plant, and not be so thick as to cause damage with its weight.[101]

Frost on a thistle in Hausdülmen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

A spiderweb covered in frost

Ice on deciduous tree after freezing rain

Yukimarimo at South Pole Station, Antarctica, in 2008

Ablation

Ablation of ice refers to both its melting and its dissolution.[103]

The melting of ice entails the breaking of hydrogen bonds between the water molecules. The ordering of the molecules in the solid breaks down to a less ordered state and the solid melts to become a liquid. This is achieved by increasing the internal energy of the ice beyond the melting point. When ice melts it absorbs as much energy as would be required to heat an equivalent amount of water by 80 °C. While melting, the temperature of the ice surface remains constant at 0 °C. The rate of the melting process depends on the efficiency of the energy exchange process. An ice surface in fresh water melts solely by free convection with a rate that depends linearly on the water temperature, T∞, when T∞ is less than 3.98 °C, and superlinearly when T∞ is equal to or greater than 3.98 °C, with the rate being proportional to (T∞ − 3.98 °C)α, with α = 5/3 for T∞ much greater than 8 °C, and α = 4/3 for in between temperatures T∞.[104]

In salty ambient conditions, dissolution rather than melting often causes the ablation of ice. For example, the temperature of the Arctic Ocean is generally below the melting point of ablating sea ice. The phase transition from solid to liquid is achieved by mixing salt and water molecules, similar to the dissolution of sugar in water, even though the water temperature is far below the melting point of the sugar. However, the dissolution rate is limited by salt concentration and is therefore slower than melting.[105]

Role in human activities

Cooling

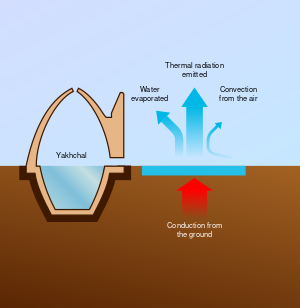

Ice has long been valued as a means of cooling. In 400 BC Iran, Persian engineers had already developed techniques for ice storage in the desert through the summer months. During the winter, ice was transported from harvesting pools and nearby mountains in large quantities to be stored in specially designed, naturally cooled refrigerators, called yakhchal (meaning ice storage). Yakhchals were large underground spaces (up to 5000 m3) that had thick walls (at least two meters at the base) made of a specific type of mortar called sarooj made from sand, clay, egg whites, lime, goat hair, and ash. The mortar was resistant to heat transfer, helping to keep the ice cool enough not to melt; it was also impenetrable by water. Yakhchals often included a qanat and a system of windcatchers that could lower internal temperatures to frigid levels, even during the heat of the summer. One use for the ice was to create chilled treats for royalty.[106][107]

Harvesting

There were thriving industries in 16th–17th century England whereby low-lying areas along the Thames Estuary were flooded during the winter, and ice harvested in carts and stored inter-seasonally in insulated wooden houses as a provision to an icehouse often located in large country houses, and widely used to keep fish fresh when caught in distant waters. This was allegedly copied by an Englishman who had seen the same activity in China. Ice was imported into England from Norway on a considerable scale as early as 1823.[108]

In the United States, the first cargo of ice was sent from New York City to Charleston, South Carolina, in 1799,[108] and by the first half of the 19th century, ice harvesting had become a big business. Frederic Tudor, who became known as the "Ice King", worked on developing better insulation products for long distance shipments of ice, especially to the tropics; this became known as the ice trade.[109]

Between 1812 and 1822, under Lloyd Hesketh Bamford Hesketh's instruction, Gwrych Castle was built with 18 large towers, one of those towers is called the 'Ice Tower'. Its sole purpose was to store Ice.[110]

Trieste sent ice to Egypt, Corfu, and Zante; Switzerland, to France; and Germany sometimes was supplied from Bavarian lakes.[108] From 1930s and up until 1994, the Hungarian Parliament building used ice harvested in the winter from Lake Balaton for air conditioning.[111]

Ice houses were used to store ice formed in the winter, to make ice available all year long, and an early type of refrigerator known as an icebox was cooled using a block of ice placed inside it. Many cities had a regular ice delivery service during the summer. The advent of artificial refrigeration technology made the delivery of ice obsolete.[112]

Ice is still harvested for ice and snow sculpture events. For example, a swing saw is used to get ice for the Harbin International Ice and Snow Sculpture Festival each year from the frozen surface of the Songhua River.[113]

Artificial production

The earliest known written process to artificially make ice is by the 13th-century writings of Arab historian Ibn Abu Usaybia in his book Kitab Uyun al-anba fi tabaqat-al-atibba concerning medicine in which Ibn Abu Usaybia attributes the process to an even older author, Ibn Bakhtawayhi, of whom nothing is known.[114]

Ice is now produced on an industrial scale, for uses including food storage and processing, chemical manufacturing, concrete mixing and curing, and consumer or packaged ice.[115] Most commercial icemakers produce three basic types of fragmentary ice: flake, tubular and plate, using a variety of techniques.[115] Large batch ice makers can produce up to 75 tons of ice per day.[116] In 2002, there were 426 commercial ice-making companies in the United States, with a combined value of shipments of $595,487,000.[117] Home refrigerators can also make ice with a built in icemaker, which will typically make ice cubes or crushed ice. The first such device was presented in 1965 by Frigidaire.[118]

Land travel

Ice forming on roads is a common winter hazard, and black ice particularly dangerous because it is very difficult to see. It is both very transparent, and often forms specifically in shaded (and therefore cooler and darker) areas, i.e. beneath overpasses.[119]

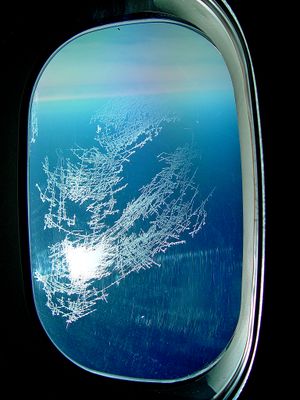

Whenever there is freezing rain or snow which occurs at a temperature near the melting point, it is common for ice to build up on the windows of vehicles. Often, snow melts, re-freezes, and forms a fragmented layer of ice which effectively "glues" snow to the window. In this case, the frozen mass is commonly removed with ice scrapers.[120] A thin layer of ice crystals can also form on the inside surface of car windows during sufficiently cold weather. In the 1970s and 1980s, some vehicles such as Ford Thunderbird could be upgraded with heated windshields as the result. This technology fell out of style as it was too expensive and prone to damage, but rear-window defrosters are cheaper to maintain and so are more widespread.[121]

In sufficiently cold places, the layers of ice on water surfaces can get thick enough for ice roads to be built. Some regulations specify that the minimum safe thickness is 4 in (10 cm) for a person, 7 in (18 cm) for a snowmobile and 15 in (38 cm) for an automobile lighter than 5 tonnes. For trucks, effective thickness varies with load - i.e. a vehicle with 9-ton total weight requires a thickness of 20 in (51 cm). Notably, the speed limit for a vehicle moving at a road which meets its minimum safe thickness is 25 km/h (15 mph), going up to 35 km/h (25 mph) if the road's thickness is 2 or more times larger than the minimum safe value.[122] There is a known instance where a railroad has been built on ice.[123]

The most famous ice road had been the Road of Life across Lake Ladoga. It operated in the winters of 1941–1942 and 1942–1943, when it was the only land route available to the Soviet Union to relieve the Siege of Leningrad by the German Army Group North.[124] The trucks moved hundreds of thousands tonnes of supplies into the city, and hundreds of thousands of civilians were evacuated.[125] It is now a World Heritage Site.[126]

Water-borne travel

For ships, ice presents two distinct hazards. Firstly, spray and freezing rain can produce an ice build-up on the superstructure of a vessel sufficient to make it unstable, potentially to the point of capsizing.[127] Earlier, crewmembers were regularly forced to manually hack off ice build-up. After 1980s, spraying de-icing chemicals or melting the ice through hot water/steam hoses became more common.[128] Secondly, icebergs – large masses of ice floating in water (typically created when glaciers reach the sea) – can be dangerous if struck by a ship when underway. Icebergs have been responsible for the sinking of many ships, the most famous being the Titanic.[129]

For harbors near the poles, being ice-free, ideally all year long, is an important advantage. Examples are Murmansk (Russia), Petsamo (Russia, formerly Finland), and Vardø (Norway). Harbors which are not ice-free are opened up using specialized vessels, called icebreakers.[130] Icebreakers are also used to open routes through the sea ice for other vessels, as the only alternative is to find the openings called "polynyas" or "leads". A widespread production of icebreakers began during the 19th century. Earlier designs simply had reinforced bows in a spoon-like or diagonal shape to effectively crush the ice. Later designs attached a forward propeller underneath the protruding bow, as the typical rear propellers were incapable of effectively steering the ship through the ice [130]

Air travel

For aircraft, ice can cause a number of dangers. As an aircraft climbs, it passes through air layers of different temperature and humidity, some of which may be conducive to ice formation. If ice forms on the wings or control surfaces, this may adversely affect the flying qualities of the aircraft. In 1919, during the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic, the British aviators Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten Brown encountered such icing conditions – Brown left the cockpit and climbed onto the wing several times to remove ice which was covering the engine air intakes of the Vickers Vimy aircraft they were flying.[133]

One vulnerability effected by icing that is associated with reciprocating internal combustion engines is the carburetor. As air is sucked through the carburetor into the engine, the local air pressure is lowered, which causes adiabatic cooling. Thus, in humid near-freezing conditions, the carburetor will be colder, and tend to ice up. This will block the supply of air to the engine, and cause it to fail. Between 1969 and 1975, 468 such instances were recorded, causing 75 aircraft losses, 44 fatalities and 202 serious injuries.[134] Thus, carburetor air intake heaters were developed. Further, reciprocating engines with fuel injection do not require carburetors in the first place.[135]

Jet engines do not experience carb icing, but they can be affected by the moisture inherently present in jet fuel freezing and forming ice crystals, which can potentially clog up fuel intake to the engine. Fuel heaters and/or de-icing additives are used to address the issue.[136]

Recreation and sports

Ice plays a central role in winter recreation and in many sports such as ice skating, tour skating, ice hockey, bandy, ice fishing, ice climbing, curling, broomball and sled racing on bobsled, luge and skeleton. Many of the different sports played on ice get international attention every four years during the Winter Olympic Games.[137]

Small boat-like craft can be mounted on blades and be driven across the ice by sails. This sport is known as ice yachting, and it had been practiced for centuries.[138][139] Another vehicular sport is ice racing, where drivers must speed on lake ice, while also controlling the skid of their vehicle (similar in some ways to dirt track racing). The sport has even been modified for ice rinks.[140]

Other uses

As thermal ballast

- Ice is still used to cool and preserve food in portable coolers.[112]

- Ice cubes or crushed ice can be used to cool drinks. As the ice melts, it absorbs heat and keeps the drink near 0 °C (32 °F).[141]

- Ice can be used as part of an air conditioning system, using battery- or solar-powered fans to blow hot air over the ice. This is especially useful during heat waves when power is out and standard (electrically powered) air conditioners do not work.[142]

- Ice can be used (like other cold packs) to reduce swelling (by decreasing blood flow) and pain by pressing it against an area of the body.[143]

As structural material

- Engineers used the substantial strength of pack ice when they constructed Antarctica's first floating ice pier in 1973.[144] Such ice piers are used during cargo operations to load and offload ships. Fleet operations personnel make the floating pier during the winter. They build upon naturally occurring frozen seawater in McMurdo Sound until the dock reaches a depth of about 22 أقدام (6.7 m). Ice piers are inherently temporary structures, although some can last as long as 10 years. Once a pier is no longer usable, it is towed to sea with an icebreaker.[145]

- Structures and ice sculptures are built out of large chunks of ice or by spraying water[123] The structures are mostly ornamental (as in the case with ice castles), and not practical for long-term habitation. Ice hotels exist on a seasonal basis in a few cold areas.[146] Igloos are another example of a temporary structure, made primarily from snow.[147]

- Engineers can also use ice to destroy. In mining, drilling holes in rock structures and then pouring water during cold weather is an accepted alternative to using dynamite, as the rock cracks when the water expands as ice.[9]

- During World War II, Project Habbakuk was an Allied programme which investigated the use of pykrete (wood fibers mixed with ice) as a possible material for warships, especially aircraft carriers, due to the ease with which a vessel immune to torpedoes, and a large deck, could be constructed by ice. A small-scale prototype was built,[148] but it soon turned out the project would cost far more than a conventional aircraft carrier while being many times slower and also vulnerable to melting.[149]

- Ice has even been used as the material for a variety of musical instruments, for example by percussionist Terje Isungset.[150]

Impacts of climate change

Historical

Greenhouse gas emissions from human activities unbalance the Earth's energy budget and so cause an accumulation of heat.[152] About 90% of that heat is added to ocean heat content, 1% is retained in the atmosphere and 3-4% goes to melt major parts of the cryosphere.[152] Between 1994 and 2017, 28 trillion tonnes of ice were lost around the globe as the result.[151] Arctic sea ice decline accounted for the single largest loss (7.6 trillion tonnes), followed by the melting of Antarctica's ice shelves (6.5 trillion tonnes), the retreat of mountain glaciers (6.1 trillion tonnes), the melting of the Greenland ice sheet (3.8 trillion tonnes) and finally the melting of the Antarctic ice sheet (2.5 trillion tonnes) and the limited losses of the sea ice in the Southern Ocean (0.9 trillion tonnes).[151]

Other than the sea ice (which already displaces water due to Archimedes' principle), these losses are a major cause of sea level rise (SLR) and they are expected to intensify in the future. In particular, the melting of the West Antarctic ice sheet may accelerate substantially as the floating ice shelves are lost and can no longer buttress the glaciers. This would trigger poorly understood marine ice sheet instability processes, which could then increase the SLR expected for the end of the century (between 30 cm (1 ft) and 1 m (3+1⁄2 ft), depending on future warming), by tens of centimeters more.[153]

Ice loss in Greenland and Antarctica also produces large quantities of fresh meltwater, which disrupts the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) and the Southern Ocean overturning circulation, respectively.[154] These two halves of the thermohaline circulation are very important for the global climate. A continuation of high meltwater flows may cause a severe disruption (up to a point of a "collapse") of either circulation, or even both of them. Either event would be considered an example of tipping points in the climate system, because it would be extremely difficult to reverse.[154] AMOC is generally not expected to collapse during the 21st century, while there is only limited knowledge about the Southern Ocean circulation.[153]

Another example of ice-related tipping point is permafrost thaw. While the organic content in the permafrost causes CO2 and methane emissions once it thaws and begins to decompose,[154] ice melting liqufies the ground, causing anything built above the former permafrost to collapse. By 2050, the economic damages from such infrastructure loss are expected to cost tens of billions of dollars.[155]

Predictions

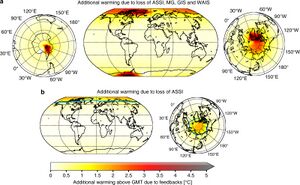

In the future, the Arctic Ocean is likely to lose effectively all of its sea ice during at least some Septembers (the end of the ice melting season), although some of the ice would refreeze during the winter. I.e. an ice-free September is likely to occur once in every 40 years if global warming is at 1.5 °C (2.7 °F), but would occur once in every 8 years at 2 °C (3.6 °F) and once in every 1.5 years at 3 °C (5.4 °F).[157] This would affect the regional and global climate due to the ice-albedo feedback. Because ice is highly reflective of solar energy, persistent sea ice cover lowers local temperatures. Once that ice cover melts, the darker ocean waters begin to absorb more heat, which also helps to melt the remaining ice.[160]

Global losses of sea ice between 1992 and 2018, almost all of them in the Arctic, have already had the same impact as 10% of greenhouse gas emissions over the same period.[161] If all the Arctic sea ice was gone every year between June and September (polar day, when the Sun is constantly shining), temperatures in the Arctic would increase by over 1.5 °C (2.7 °F), while the global temperatures would increase by around 0.19 °C (0.34 °F).[156]

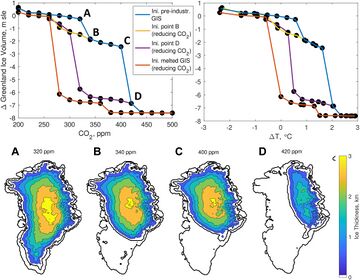

By 2100, at least a quarter of mountain glaciers outside of Greenland and Antarctica would melt,[163] and effectively all ice caps on non-polar mountains are likely to be lost around 200 years after global warming reaches 2 °C (3.6 °F).[158][159] The West Antarctic ice sheet is highly vulnerable and will likely disappear even if the warming does not progress further,[164][165][166][167] although it could take around 2,000 years before its loss is complete.[158][159] The Greenland ice sheet will most likely be lost with the sustained warming between 1.7 °C (3.1 °F) and 2.3 °C (4.1 °F),[168] although its total loss requires around 10,000 years.[158][159] Finally, the East Antarctic ice sheet will take at least 10,000 years to melt entirely, which requires a warming of between 5 °C (9.0 °F) and 10 °C (18 °F).[158][159]

If all the ice on Earth melted, it would result in about 70 m (229 ft 8 in) of sea level rise,[169] with some 53.3 m (174 ft 10 in) coming from East Antarctica.[58] Due to isostatic rebound, the ice-free land would eventually become 301 m (987 ft 6 in) higher in Greenland and 494 m (1،620 ft 9 in) in Antarctica, on average. Areas in the center of each landmass would become up to 783 m (2،568 ft 11 in) and 936 m (3،070 ft 10 in) higher, respectively.[170] The impact on global temperatures from losing West Antartica, mountain glaciers and the Greenland ice sheet is estimated at 0.05 °C (0.090 °F), 0.08 °C (0.14 °F) and 0.13 °C (0.23 °F), respectively,[156] while the lack of the East Antarctic ice sheet would increase the temperatures by 0.6 °C (1.1 °F).[158][159]

Non-water

The solid phases of several other volatile substances are also referred to as ices; generally a volatile is classed as an ice if its melting or sublimation point lies above or around 100 K (−173 °C; −280 °F) (assuming standard atmospheric pressure). The best known example is dry ice, the solid form of carbon dioxide. Its sublimation/deposition point occurs at 194.7 K (−78.5 °C; −109.2 °F).[171]

A "magnetic analogue" of ice is also realized in some insulating magnetic materials in which the magnetic moments mimic the position of protons in water ice and obey energetic constraints similar to the Bernal-Fowler ice rules arising from the geometrical frustration of the proton configuration in water ice. These materials are called spin ice.[172]

See also

References

- ^ أ ب ت Harvey, Allan H. (2017). "Properties of Ice and Supercooled Water". In Haynes, William M.; Lide, David R.; Bruno, Thomas J. (eds.). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (97th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4987-5429-3.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر Voitkovskii, K. F., Translation of: "The mechanical properties of ice" ("Mekhanicheskie svoistva l'da"), Academy of Sciences (USSR), قالب:DTIC

- ^ Evans, S. (1965). "Dielectric Properties of Ice and Snow–a Review". Journal of Glaciology. 5 (42): 773–792. doi:10.3189/S0022143000018840. S2CID 227325642.

- ^ Physics of Ice, V. F. Petrenko, R. W. Whitworth, Oxford University Press, 1999, ISBN 9780198518945

- ^ Bernal, J. D.; Fowler, R. H. (1933). "A Theory of Water and Ionic Solution, with Particular Reference to Hydrogen and Hydroxyl Ions". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1 (8): 515. Bibcode:1933JChPh...1..515B. doi:10.1063/1.1749327.

- ^ Bjerrum, N (11 April 1952). "Structure and Properties of Ice". Science. 115 (2989): 385–390. Bibcode:1952Sci...115..385B. doi:10.1126/science.115.2989.385. PMID 17741864.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ أ ب Richardson, Eliza (20 June 2021). "Ice, Water, and Vapor". LibreTexts Geosciences (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ أ ب Akyurt, M.; Zaki, G.; Habeebullah, B. (15 May 2002). "Freezing phenomena in ice–water systems". Energy Conversion and Management. 43 (14): 1773–1789. Bibcode:2002ECM....43.1773A. doi:10.1016/S0196-8904(01)00129-7.

- ^ Tyson, Neil deGrasse. "Water, Water". haydenplanetarium.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011.

- ^ Sea Ice Ecology Archived 21 مارس 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Acecrc.sipex.aq. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ أ ب "Ice – a special substance" (in الإنجليزية). European Space Agency. 16 April 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ أ ب Lynch, David K.; Livingston, William Charles (2001). Color and light in nature. Cambridge University Press. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-0-521-77504-5.

- ^ Walters, S. Max (January 1946). "Hardness of Ice at Low Temperatures". Polar Record. 4 (31): 344–345. Bibcode:1946PoRec...4..344.. doi:10.1017/S003224740004239X. S2CID 250049037.

- ^ David, Carl (8 August 2016). "Verwiebe's '3-D' Ice phase diagram reworked". Chemistry Education Materials.

- ^ Wagner, Wolfgang; Saul, A.; Pruss, A. (May 1994). "International Equations for the Pressure Along the Melting and Along the Sublimation Curve of Ordinary Water Substance". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 23 (3): 515–527. Bibcode:1994JPCRD..23..515W. doi:10.1063/1.555947.

- ^ Murphy, D. M. (2005). "Review of the vapour pressures of ice and supercooled water for atmospheric applications". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 131 (608): 1539–1565. Bibcode:2005QJRMS.131.1539M. doi:10.1256/qj.04.94. S2CID 122365938.

- ^ "SI base units". Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ^ "Information for users about the proposed revision of the SI" (PDF). Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Iglev, H.; Schmeisser, M.; Simeonidis, K.; Thaller, A.; Laubereau, A. (2006). "Ultrafast superheating and melting of bulk ice". Nature. 439 (7073): 183–186. Bibcode:2006Natur.439..183I. doi:10.1038/nature04415. PMID 16407948. S2CID 4404036.

- ^ Metcalfe, Tom (9 March 2021). "Exotic crystals of 'ice 19' discovered". Live Science (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ La Placa, S. J.; Hamilton, W. C.; Kamb, B.; Prakash, A. (1972). "On a nearly proton ordered structure for ice IX". Journal of Chemical Physics. 58 (2): 567–580. Bibcode:1973JChPh..58..567L. doi:10.1063/1.1679238.

- ^ Klotz, S.; Besson, J. M.; Hamel, G.; Nelmes, R. J.; Loveday, J. S.; Marshall, W. G. (1999). "Metastable ice VII at low temperature and ambient pressure". Nature. 398 (6729): 681–684. Bibcode:1999Natur.398..681K. doi:10.1038/19480. S2CID 4382067.

- ^ Dutch, Stephen. "Ice Structure". University of Wisconsin Green Bay. Archived from the original on 16 October 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ^ Salzmann, Christoph G.; Radaelli, Paolo G.; Hallbrucker, Andreas; Mayer, Erwin; Finney, John L. (24 March 2006). "The Preparation and Structures of Hydrogen Ordered Phases of Ice". Science. 311 (5768): 1758–1761. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1758S. doi:10.1126/science.1123896. PMID 16556840. S2CID 44522271.

- ^ Sanders, Laura (11 September 2009). "A Very Special Snowball". Science News. Archived from the original on 14 September 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- ^ Militzer, Burkhard; Wilson, Hugh F. (2 November 2010). "New Phases of Water Ice Predicted at Megabar Pressures". Physical Review Letters. 105 (19): 195701. arXiv:1009.4722. Bibcode:2010PhRvL.105s5701M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.195701. PMID 21231184. S2CID 15761164.

- ^ MacMahon, J. M. (1970). "Ground-State Structures of Ice at High-Pressures". Physical Review B. 84 (22): 220104. arXiv:1106.1941. Bibcode:2011PhRvB..84v0104M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.84.220104. S2CID 117870442.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (9 December 2004). "Astronomers Contemplate Icy Volcanoes in Far Places". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Prockter, Louise M. (2005). "Ice in the Solar System" (PDF). Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest. 26 (2): 175. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ Showman, A. (1997). "Coupled Orbital and Thermal Evolution of Ganymede" (PDF). Icarus. 129 (2): 367–383. Bibcode:1997Icar..129..367S. doi:10.1006/icar.1997.5778.

- ^ Debennetti, Pablo G.; Stanley, H. Eugene (2003). "Supercooled and Glassy Water" (PDF). Physics Today. 56 (6): 40–46. Bibcode:2003PhT....56f..40D. doi:10.1063/1.1595053. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ Lübken, F.-J.; Lautenbach, J.; Höffner, J.; Rapp, M.; Zecha, M. (March 2009). "First continuous temperature measurements within polar mesosphere summer echoes". Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics. 71 (3–4): 453–463. Bibcode:2009JASTP..71..453L. doi:10.1016/j.jastp.2008.06.001.

- ^ Loerting, Thomas; Salzmann, Christoph; Kohl, Ingrid; Mayer, Erwin; Hallbrucker, Andreas (2001). "A second distinct structural "state" of high-density amorphous ice at 77 K and 1 bar". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 3 (24): 5355–5357. Bibcode:2001PCCP....3.5355L. doi:10.1039/b108676f. S2CID 59485355.

- ^ Zyga, Lisa (25 April 2013). "New phase of water could dominate the interiors of Uranus and Neptune". Phys.org.

- ^ أ ب Rosenberg, Robert (2005). "Why Is Ice Slippery?". Physics Today. 58 (12): 50–54. Bibcode:2005PhT....58l..50R. doi:10.1063/1.2169444.

- ^ أ ب Chang, Kenneth (21 February 2006). "Explaining Ice: The Answers Are Slippery". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- ^ Canale, L. (4 September 2019). "Nanorheology of Interfacial Water during Ice Gliding". Physical Review X. 9 (4): 041025. arXiv:1907.01316. Bibcode:2019PhRvX...9d1025C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.9.041025.

- ^ Makkonen, Lasse; Tikanmäki, Maria (June 2014). "Modeling the friction of ice". Cold Regions Science and Technology. 102: 84–93. Bibcode:2014CRST..102...84M. doi:10.1016/j.coldregions.2014.03.002.

- ^ Dorbolo, S. (2016). "Rotation of melting ice disks due to melt fluid flow". Physical Review E. 93 (3): 033112. arXiv:1510.06505. Bibcode:2016PhRvE..93c3112D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.93.033112. PMID 27078452.

- ^ Stepanova, E. V.; Chaplina, T. O. (December 2019). "Vortex Flow Formation by a Melting Ice Block". Fluid Dynamics (in الإنجليزية). 54 (7): 1002–1008. Bibcode:2019FlDy...54.1002S. doi:10.1134/S0015462819070140. ISSN 0015-4628.

- ^ أ ب Bolch, Tobias; Shea, Joseph M.; Liu, Shiyin; Azam, Farooq M.; Gao, Yang; Gruber, Stephan; Immerzeel, Walter W.; Kulkarni, Anil; Li, Huilin; Tahir, Adnan A.; Zhang, Guoqing; Zhang, Yinsheng (5 January 2019). "Status and Change of the Cryosphere in the Extended Hindu Kush Himalaya Region". The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment. pp. 209–255. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92288-1_7. ISBN 978-3-319-92287-4. S2CID 134814572.

- ^ أ ب Scott, Christopher A.; Zhang, Fan; Mukherji, Aditi; Immerzeel, Walter; Mustafa, Daanish; Bharati, Luna (5 January 2019). "Water in the Hindu Kush Himalaya". The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment. pp. 257–299. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92288-1_8. ISBN 978-3-319-92287-4. S2CID 133800578.

- ^ "WMO SEA-ICE NOMENCLATURE" Archived 5 يونيو 2013 at the Wayback Machine (Multi-language Archived 14 أبريل 2012 at the Wayback Machine) World Meteorological Organization / Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ^ Englezos, Peter (1993). "Clathrate hydrates". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 32 (7): 1251–1274. doi:10.1021/ie00019a001.

- ^ Gas Hydrate: What is it?, U.S. Geological Survey, 31 August 2009, https://woodshole.er.usgs.gov/project-pages/hydrates/what.html, retrieved on 28 December 2014

- ^ WMO Sea-ice Nomenclature. Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization. 2014. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://library.wmo.int/records/item/41953-wmo-sea-ice-nomenclature. - ^ Benn, D.; Warren, C.; Mottram, R. (2007). "Calving processes and the dynamics of calving glaciers" (PDF). Earth-Science Reviews. 82 (3–4): 143–179. Bibcode:2007ESRv...82..143B. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2007.02.002.

- ^ Robel, Alexander A. (2017-03-01). "Thinning sea ice weakens buttressing force of iceberg mélange and promotes calving". Nature Communications (in الإنجليزية). 8: 14596. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814596R. doi:10.1038/ncomms14596. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5339875. PMID 28248285.

- ^ Smedsrud, Lars H.; Skogseth, Ragnheid (2006). Field Measurements of Arctic Grease Ice Properties and Processes. Cold Regions Science and Technology 44. pp. 171–183.

- ^ Roach, Lettie A.; Horvat, Christopher; Dean, Samuel M.; Bitz, Cecilia M. (6 May 2018). "An Emergent Sea Ice Floe Size Distribution in a Global Coupled Ocean-Sea Ice Model". Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 123 (6): 4322–4337. Bibcode:2018JGRC..123.4322R. doi:10.1029/2017JC013692.

- ^ Qin Zhang; Roger Skjetne (13 February 2018). Sea Ice Image Processing with MATLAB. CRC. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-351-06918-2.

- ^ Leppäranta, Matti; Hakala, Risto (25 April 1991). "The structure and strength of first-year ice ridges in the Baltic Sea". Cold Regions Science and Technology. 20 (3): 295–311. doi:10.1016/0165-232X(92)90036-T.

- ^ Squire, Vernon A. (2020). "Ocean Wave Interactions with Sea Ice: A Reappraisal". Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 52 (1): 37–60. Bibcode:2020AnRFM..52...37S. doi:10.1146/annurev-fluid-010719-060301. ISSN 0066-4189. S2CID 198458049.

- ^ "'Ice eggs' cover Finland beach in rare weather event". BBC News (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). 2019-11-07. Retrieved 2022-04-22.

- ^ geographyrealm (2019-11-14). "How Ice Balls Form". Geography Realm (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- ^ "How Greenland would look without its ice sheet". BBC News. 14 December 2017. Archived from the original on 7 December 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ أ ب Fretwell, P.; Pritchard, H. D.; Vaughan, D. G.; Bamber, J. L.; Barrand, N. E.; Bell, R.; Bianchi, C.; Bingham, R. G.; Blankenship, D. D.; Casassa, G.; Catania, G.; Callens, D.; Conway, H.; Cook, A. J.; Corr, H. F. J.; Damaske, D.; Damm, V.; Ferraccioli, F.; Forsberg, R.; Fujita, S.; Gim, Y.; Gogineni, P.; Griggs, J. A.; Hindmarsh, R. C. A.; Holmlund, P.; Holt, J. W.; Jacobel, R. W.; Jenkins, A.; Jokat, W.; Jordan, T.; King, E. C.; Kohler, J.; Krabill, W.; Riger-Kusk, M.; Langley, K. A.; Leitchenkov, G.; Leuschen, C.; Luyendyk, B. P.; Matsuoka, K.; Mouginot, J.; Nitsche, F. O.; Nogi, Y.; Nost, O. A.; Popov, S. V.; Rignot, E.; Rippin, D. M.; Rivera, A.; Roberts, J.; Ross, N.; Siegert, M. J.; Smith, A. M.; Steinhage, D.; Studinger, M.; Sun, B.; Tinto, B. K.; Welch, B. C.; Wilson, D.; Young, D. A.; Xiangbin, C.; Zirizzotti, A. (28 February 2013). "Bedmap2: improved ice bed, surface and thickness datasets for Antarctica". The Cryosphere. 7 (1): 375–393. Bibcode:2013TCry....7..375F. doi:10.5194/tc-7-375-2013. hdl:1808/18763.

- ^ McGee, David; Gribkoff, Elizabeth (4 August 2022). "Permafrost". MIT Climate Portal. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ Lacelle, Denis; Fisher, David A.; Verret, Marjolaine; Pollard, Wayne (17 February 2022). "Improved prediction of the vertical distribution of ground ice in Arctic-Antarctic permafrost sediments". Communications Earth & Environment. 3 (31): 31. Bibcode:2022ComEE...3...31L. doi:10.1038/s43247-022-00367-z. S2CID 246872753.

- ^ Huryn, Alexander D.; Gooseff, Michael N.; Hendrickson, Patrick J.; Briggs, Martin A.; Tape, Ken D.; Terry, Neil C. (2020-10-13). "Aufeis fields as novel groundwater-dependent ecosystems in the arctic cryosphere". Limnology and Oceanography. 66 (3): 607–624. doi:10.1002/lno.11626. ISSN 0024-3590. S2CID 225139804.

- ^ Johnson, Chris; Affolter, Matthew D.; Inkenbrandt, Paul; Mosher, Cam (July 1, 2017). "14 Glaciers". An Introduction to Geology.

- ^ "Ice Jams". Nws.noaa.gov. 2013-03-13. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ Staff writer (7 February 2006). "Ice Dams: Taming An Icy River". Popular Mechanics (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ "Crop Circles in the Ice: How Do Ice Circles Form?". Modern Notion (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 22 December 2015. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ Dorbolo, S; Adami, N.; Dubois, C.; Caps, H.; Vandewalle, N.; Barbois-Texier, B. (2016). "Rotation of melting ice disks due to melt fluid flow". Phys. Rev. E. 93 (3): 1–5. arXiv:1510.06505. Bibcode:2016PhRvE..93c3112D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.93.033112. hdl:2268/195696. PMID 27078452. S2CID 118380381.

- ^ Petrenko, Victor F. and Whitworth, Robert W. (1999) Physics of ice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 27–29, ISBN 0191581348

- ^ Eranti, E. and Lee, George C. (1986) Cold region structural engineering. New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 51, ISBN 0070370346.

- ^ Dionne, J (November 1979). "Ice action in the lacustrine environment. A review with particular reference to subarctic Quebec, Canada". Earth-Science Reviews. 15 (3): 185–212. Bibcode:1979ESRv...15..185D. doi:10.1016/0012-8252(79)90082-5.

- ^ Schwarz, Phil (19 February 2018). "Dangerous shelf ice forms along Lake Michigan". abc7chicago.com. Retrieved 2020-02-05.

- ^ "Candle ice". Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. 2012-02-20. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

- ^ Mason, Basil John (1971). Physics of Clouds. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-851603-3.

- ^ Christner, Brent C.; Morris, Cindy E.; Foreman, Christine M.; Cai, Rongman; Sands, David C. (29 February 2008). "Ubiquity of Biological Ice Nucleators in Snowfall". Science. 319 (5867): 1214. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1214C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.714.4002. doi:10.1126/science.1149757. PMID 18309078. S2CID 39398426.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "Cloud seeding". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ^ Pelley, Janet (30 May 2016). "Does cloud seeding really work?". Chemical and Engineering News. 94 (22): 18–21. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ Sanders, Kristopher J.; Barjenbruch, Brian L. (1 August 2016). "Analysis of Ice-to-Liquid Ratios during Freezing Rain and the Development of an Ice Accumulation Model". Weather Forecasting. 31 (4): 1041–1060. Bibcode:2016WtFor..31.1041S. doi:10.1175/WAF-D-15-0118.1.

- ^ أ ب Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "Hail". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ أ ب ت Alaska Air Flight Service Station (10 April 2007). "SA-METAR". Federal Aviation Administration via the Internet Wayback Machine. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ Jewell, Ryan; Brimelow, Julian (17 August 2004). "P9.5 Evaluation of an Alberta Hail Growth Model Using Severe Hail Proximity Soundings in the United States" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ National Severe Storms Laboratory (23 April 2007). "Aggregate hailstone". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 10 August 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ Brimelow, Julian C.; Reuter, Gerhard W.; Poolman, Eugene R. (2002). "Modeling Maximum Hail Size in Alberta Thunderstorms". Weather and Forecasting. 17 (5): 1048–1062. Bibcode:2002WtFor..17.1048B. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2002)017<1048:MMHSIA>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Marshall, Jacque (10 April 2000). "Hail Fact Sheet". University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Archived from the original on 15 October 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ "Hail storms rock southern Qld". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 19 October 2004. Archived from the original on 6 March 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ Bath, Michael; Degaura, Jimmy (1997). "Severe Thunderstorm Images of the Month Archives". Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ Wolf, Pete (16 January 2003). "Meso-Analyst Severe Weather Guide". University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Archived from the original on 20 March 2003. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ Downing, Thomas E.; Olsthoorn, Alexander A.; Tol, Richard S. J. (1999). Climate, change and risk. Routledge. pp. 41–43. ISBN 978-0-415-17031-4.

- ^ "Hail (glossary entry)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2007.

- ^ "Sleet (glossary entry)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 18 February 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2007.

- ^ "What causes ice pellets (sleet)?". Weatherquestions.com. Archived from the original on 30 November 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ "Rime and Graupel". U.S. Department of Agriculture Electron Microscopy Unit, Beltsville Agricultural Research Center. Archived from the original on 2017-07-11. Retrieved 2020-03-23.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Diamond Dust". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 3 April 2009. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ Makkonen, Lase (15 November 2000). "Models for the growth of rime, glaze, icicles and wet snow deposits on structures". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A. 358 (1776): 2913–2939. doi:10.1098/rsta.2000.0690.

- ^ "Dealing with and preventing ice dams". University of Minnesota Extension. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "What causes frost?". Archived from the original on 2007-12-10. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- ^ "Weather Facts: Frost hollow – Weather UK – weatheronline.co.uk". weatheronline.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2013-02-12.

- ^ Kameda, T.; Yoshimi, H.; Azuma, N.; Motoyama, H. (1999). "Observation of "yukimarimo" on the snow surface of the inland plateau, Antarctic ice sheet". Journal of Glaciology (in الإنجليزية). 45 (150): 394–396. Bibcode:1999JGlac..45..394K. doi:10.1017/S0022143000001891. ISSN 0022-1430.

- ^ Podolskiy, Evgeny Andreevich; Nygaard, Bjørn Egil Kringlebotn; Nishimura, Kouichi; Makkonen, Lasse; Lozowski, Edward Peter (27 June 2012). "Study of unusual atmospheric icing at Mount Zao, Japan, using the Weather Research and Forecasting model". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 112 (D2). Bibcode:2012JGRD..11712106P. doi:10.1029/2011JD017042.

- ^ "hard rime (Glossary of Meteorology)" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). American Meteorological Society. 30 March 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "soft rime (Glossary of Meteorology)" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). American Meteorological Society. 30 March 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Beerling, D. J.; Terry, A. C.; Mitchell, P. L.; Callaghan, T. V.; Gwynn-Jones, D.; Lee, J. A. (April 2001). "Time to chill: effects of simulated global change on leaf ice nucleation temperatures of subarctic vegetation". American Journal of Botany (in الإنجليزية). 88 (4): 628–633. doi:10.2307/2657062. JSTOR 2657062. PMID 11302848.

- ^ أ ب Pan, Qingmin; Lu, Yongzong; Hu, Huijie; Hu, Yongguang (15 December 2023). "Review and research prospects on sprinkler irrigation frost protection for horticultural crops". Scientia Horticulture. 326. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112775.

- ^ "Wind machines for minimizing cold injury to horticultural crops". Ontario state government. June 2010. Retrieved 30 May 2024.

- ^ Paterson, W. S. B. (1994). Physics of Glaciers (in الإنجليزية). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-7506-4742-7.

- ^ Keitzl, Thomas; Mellado, Juan Pedro; Notz, Dirk (2016). "Impact of Thermally Driven Turbulence on the Bottom Melting of Ice". J. Phys. Oceanogr. 46 (4): 1171–1187. Bibcode:2016JPO....46.1171K. doi:10.1175/JPO-D-15-0126.1. hdl:2117/189387.

- ^ Woods, Andrew W. (1992). "Melting and dissolving". J. Fluid Mech. 239: 429–448. Bibcode:1992JFM...239..429W. doi:10.1017/S0022112092004476 (inactive 1 November 2024). S2CID 122680287.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of نوفمبر 2024 (link) - ^ Hosseini, Bahareh; Namazian, Ali (2012). "An Overview of Iranian Ice Repositories, an Example of Traditional Indigenous Architecture". METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture. 29 (2): 223–234. doi:10.4305/METU.JFA.2012.2.10. hdl:11511/50831.

- ^ "Yakhchal: Ancient Refrigerators". Earth Architecture. 9 September 2009.

- ^ أ ب ت

"[[s:Collier's New Encyclopedia (1921)/{{{1}}}|{{{1}}}]]". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

"[[s:Collier's New Encyclopedia (1921)/{{{1}}}|{{{1}}}]]". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- ^ Hutton, Mercedes (23 January 2020). "The icy side to Hong Kong history". BBC. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ "Gwrych Castle: The astonishing fantasy castle saved by the dreams and bravery of a 12-year-old boy". 11 November 2020.

- ^ Kay, Nathan (3 January 2019). "The secrets and symbols of Hungary's Parliament building". CNN. Archived from the original on 17 March 2019.

- ^ أ ب Prewitt, Laura (23 July 2023). "A Chilling History" (in الإنجليزية). Science History Institute. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Ice is money in China's coldest city". The Sydney Morning Herald. AFP. 13 November 2008. Archived from the original on 2 October 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- ^ Weir, Caroline; Weir, Robin (2010). Ice Creams, Sorbets & Gelati:The Definitive Guide. p. 217.

- ^ أ ب ASHRAE. "Ice Manufacture". 2006 ASHRAE Handbook: Refrigeration. Inch-Pound Edition. قالب:Nat ISBN 1-931862-86-9.

- ^ Rydzewski, A.J. "Mechanical Refrigeration: Ice Making." Marks' Standard Handbook for Mechanical Engineers. 11th ed. McGraw Hill: New York. pp. 19–24. ISBN 978-0-07-142867-5.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau. "Ice manufacturing: 2002." Archived 22 يوليو 2017 at the Wayback Machine 2002 Economic Census.

- ^ Wroclawski, Daniel (21 July 2015). "How Does an Ice Maker Work?" (in الإنجليزية). USA Today. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ Donegan, Brian (15 December 2016). "What Is Black Ice And Why Is It So Dangerous?" (in الإنجليزية). The Weather Channel. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Dhyani, Abhishek; Choi, Wonjae; Golovin, Kevin; Tuteja, Anish (4 May 2022). "Surface design strategies for mitigating ice and snow accretion". Matter. 5 (5): 1423–1454. doi:10.1016/j.matt.2022.04.012.

- ^ Braithwaite-Smith, Gavin (14 December 2022). "A brief history of the heated windshield" (in الإنجليزية). Hagerty. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Daly, Steven; Connor, Billy; Garron, Jessica; Stuefer, Svetlana; Belz, Nathan; Bjella, Kevin (1 February 2023). Design and Operation of Ice Roads. University of Alaska Fairbanks. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://aidc.uaf.edu/media/1580/ice-road-manual_final.pdf. Retrieved on 11 April 2024. - ^ أ ب Makkonen, L. (1994) "Ice and Construction". E & FN Spon, London. ISBN 0-203-62726-1.

- ^ Glantz, David M. (2001). The Siege of Leningrad, 1941–1944: 900 Days of Terror. Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN 1-86227-124-0.

- ^ Bidlack, Richard; Lomagin, Nikita (2012). The Leningrad Blockade, 1941–1944: A New Documentary History from the Soviet Archives. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11029-6.

- ^ "Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments". Unesco World Heritage Centre.

- ^ Mintu, Shafiul; Molyneux, David (15 August 2022). "Ice accretion for ships and offshore structures. Part 1 - State of the art review". Ocean Engineering. 258. Bibcode:2022OcEng.25811501M. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.111501.

- ^ Rashid, Taimur; Khawaja, Hassan Abbas; Edvardsen, Kåre (17 August 2016). "Review of marine icing and anti-/de-icing systems". Ocean Engineering. 15 (2): 79–87. Bibcode:2016JMEnT..15...79R. doi:10.1080/20464177.2016.1216734. hdl:10037/10923.

- ^ Halpern, Samuel; Weeks, Charles (2011). Halpern, Samuel (ed.). Report into the Loss of the SS Titanic: A Centennial Reappraisal. Stroud, UK: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6210-3.

- ^ أ ب Sahari, Aaro; Matala, Saara (9 December 2021). "Of a titan, winds and power: Transnational development of the icebreaker, 1890-1954". International Journal of Maritime History. 33 (4): 722–747. doi:10.1177/08438714211062493. hdl:11250/3105943.

- ^ "Overshoes For Planes End Ice Danger". Popular Science. November 1931. p. 28 – via Google Books.

- ^ Leary, William M. (2002). We Freeze to Please: A History of NASA's Icing Research Tunnel and the Quest for Flight Safety. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. p. 10. OCLC 49558649.

- ^ "Capt. John Alcock and Lt. Arthur Whitten Brown". The Aviation History On-Line Museum. 22 July 2014.

- ^ Newman, Richard L. (1981). "Carburetor Ice Flight Testing: Use of an Anti-Icing Fuel Additive". Journal of Aircraft. 18 (1): 5–6. doi:10.2514/3.57458.

- ^ "Chapter 7: Aircraft Systems". Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge, FAA-H-8083-25B (PDF). US Dept. of Transportation, FAA. 2016. pp. 7–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-12-06. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

Carburetor heat is an anti-icing system that preheats the air before it reaches the carburetor and is intended to keep the fuel-air mixture above freezing to prevent the formation of carburetor ice.

- ^ Schmitz, Mathias; Schmitz, Gerhard (15 August 2022). "Experimental study on the accretion and release of ice in aviation jet fuel". Aerospace Science and Technology. 83: 294–303. Bibcode:2022OcEng.25811501M. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.111501.

- ^ Dichter, Heather L.; Teetzel, Sarah (23 March 2021). "The Winter Olympics: A Century of Games on Ice and Snow". The International Journal of the History of Sport. 37 (13): 1215–1235. doi:10.1080/09523367.2020.1866474.

- ^ Levine, David (19 November 2013). "Explore the History of Ice Yachting in the Hudson Valley". www.hvmag.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ "IDNIYRA | International DN Ice Yacht Racing Association". December 27, 2017. Archived from the original on December 27, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Markus, Frank. "Racing Fast 'n' Cheap: Ice Racing". Motor Trend. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ Bramen, Lisa (12 August 2011). "Why Don't Other Countries Use Ice Cubes?" (in الإنجليزية). Smithsonian. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "California utility augments 1,800 air conditioning units with "ice battery"". Ars Technica. 4 May 2017.

- ^ Deuster, Patricia A.; Singh, Anita; Pelletier, Pierre A. (2007). The U.S. Navy Seal Guide to Fitness and Nutrition. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-60239-030-0.

- ^ "Unique ice pier provides harbor for ships", Archived 23 فبراير 2011 at Wikiwix Antarctic Sun. 8 January 2006; McMurdo Station, Antarctica.

- ^ "Ocean Disposal of Man-Made Ice Piers". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 10 February 2023. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023.

- ^ O'Brien, Harriet (19 January 2007). "Ice Hotels: Cold comforts". The Independent. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ Cruickshank, Dan (2 April 2008). "What house-builders can learn from igloos". BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ Gold, L.W. (1993). "The Canadian Habbakuk Project: a Project of the National Research Council of Canada". International Glaciological Society. ISBN 0946417164.

- ^ Sir Charles Goodeve (19 April 1951). "The Ice Ship Fiasco". Evening Standard. London.

- ^ Talkington, Fiona (3 May 2005). "Terje Isungset Iceman Is Review". BBC Music. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Slater, Thomas; Lawrence, Isobel R.; Otosaka, Inès N.; Shepherd, Andrew; Gourmelen, Noel; Jakob, Livia; Tepes, Paul; Gilbert, Lin; Nienow, Peter (25 Jan 2021). "Review article: Earth's ice imbalance". The Cryosphere. 15 (1): 233–246

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Bibcode:2021TCry...15..233S. doi:10.5194/tc-15-233-2021. hdl:20.500.11820/df343a4d-6b66-4eae-ac3f-f5a35bdeef04.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Bibcode:2021TCry...15..233S. doi:10.5194/tc-15-233-2021. hdl:20.500.11820/df343a4d-6b66-4eae-ac3f-f5a35bdeef04.

- ^ أ ب von Schuckmann, Karina; Minière, Audrey.; Gues, Flora; Cuesta-Valero, Francisco José; Kirchengast, Gottfried; Adusumilli, Susheel; Straneo, Flammetta; Ablain, Michaël; Allen, Richard P.; Barker, Paul M. (17 April 2023). "Heat stored in the Earth system 1960-2020: where does the energy go?". Earth System Science Data. 15 (4): 1675-1709

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Bibcode:2023ESSD...15.1675V. doi:10.5194/essd-15-1675-2023. hdl:20.500.11850/619535.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Bibcode:2023ESSD...15.1675V. doi:10.5194/essd-15-1675-2023. hdl:20.500.11850/619535.

- ^ أ ب Fox-Kemper, B.; Hewitt, Helene T.; Xiao, C.; Aðalgeirsdóttir, G.; Drijfhout, S. S.; Edwards, T. L.; Golledge, N. R.; Hemer, M.; Kopp, R. E.; Krinner, G.; Mix, A. (2021). Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S. L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L. (eds.). "Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change" (PDF). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, US.

- ^ أ ب ت Lenton, T. M.; Armstrong McKay, D.I.; Loriani, S.; Abrams, J.F.; Lade, S.J.; Donges, J.F.; Milkoreit, M.; Powell, T.; et al. (2023). The Global Tipping Points Report 2023. University of Exeter. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://global-tipping-points.org/download/4608/. - ^ Hjort, Jan; Streletskiy, Dmitry; Doré, Guy; Wu, Qingbai; Bjella, Kevin; Luoto, Miska (11 January 2022). "Impacts of permafrost degradation on infrastructure". Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. 3 (1): 24–38. Bibcode:2022NRvEE...3...24H. doi:10.1038/s43017-021-00247-8. hdl:10138/344541. S2CID 245917456.

- ^ أ ب ت Wunderling, Nico; Willeit, Matteo; Donges, Jonathan F.; Winkelmann, Ricarda (27 October 2020). "Global warming due to loss of large ice masses and Arctic summer sea ice". Nature Communications (in الإنجليزية). 10 (1): 5177. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5177W. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18934-3. PMC 7591863. PMID 33110092.

- ^ أ ب Sigmond, Michael; Fyfe, John C.; Swart, Neil C. (2 April 2018). "Ice-free Arctic projections under the Paris Agreement". Nature Climate Change (in الإنجليزية). 2 (5): 404–408. Bibcode:2018NatCC...8..404S. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0124-y. S2CID 90444686.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Armstrong McKay, David; Abrams, Jesse; Winkelmann, Ricarda; Sakschewski, Boris; Loriani, Sina; Fetzer, Ingo; Cornell, Sarah; Rockström, Johan; Staal, Arie; Lenton, Timothy (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points". Science (in الإنجليزية). 377 (6611): eabn7950. doi:10.1126/science.abn7950. hdl:10871/131584. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 36074831. S2CID 252161375.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Armstrong McKay, David (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points – paper explainer". climatetippingpoints.info (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Dai, Aiguo; Luo, Dehai; Song, Mirong; Liu, Jiping (10 January 2019). "Arctic amplification is caused by sea-ice loss under increasing CO2". Nature Communications (in الإنجليزية). 10 (1): 121. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..121D. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07954-9. PMC 6328634. PMID 30631051.