فيروز (حجر كريم)

| Turquoise | |

|---|---|

| |

| العامة | |

| التصنيف | معادن الفوسفات |

| الصيغة (repeating unit) | CuAl 6(PO 4) 4(OH) 8·4H2O |

| تصنيف سترونز | 8.DD.15 |

| النظام البلوري | Triclinic |

| Crystal class | Pinacoidal (1) (same H–M symbol) |

| التعرف | |

| Colour | Turquoise, blue, blue-green, green |

| Crystal habit | Massive, nodular |

| Cleavage | Perfect on {001}, good on {010}, but cleavage rarely seen |

| Fracture | Conchoidal |

| Mohs scale hardness | 5–6 |

| Luster | Waxy to subvitreous |

| Streak | Bluish white |

| Diaphaneity | Opaque |

| الجاذبية النوعية | 2.6–2.9 |

| الصفات البصرية | Biaxial (+) |

| Refractive index | nα = 1.610 nβ = 1.615 nγ = 1.650 |

| Birefringence | +0.040 |

| Pleochroism | Weak |

| قابلية الانصهار | Fusible in heated HCl |

| قابلية الذوبان | Soluble in HCl |

| References | [1][2][3] |

الفيروز ((بالإنجليزية : Turquoise)) نوع من أنواع الأحجار الكريمة, وهو أزرق اللون عادة وهو عبارة عن فوسفات متميه من الألمنيوم والنحاس, ويتضمن تركيبه على معدن الحديد في بعض الأحيان, يتكون عن طريق ترسب المحاليل. نحاسي, يتكون من أبخرة النحاس الصاعدة في معدنه وسبب هذا الرأي وجود كميات قليلة من فوسفات النحاس فيه والتي تمنحه اللون الأزرق ويضفي معدن الحديد في نركيبه اللون الأخضر. حجر سهل الخدش وخفيف الوزن ضعيف جدا تتخلله كسور محارية الشكل, معرض للإصابة بالشروخ (بسبب أن بعض خاماته شديدة المسامية) ويمكن المحافظة على شكل الحجر عبر طبعه على مادة الراتنج الصمغية أو على الشمع, ذو قيمة عالية مميزة من بين المجوهرات.

من أسمائه : الفيروزج - الماكفات - البيروزة - حجر العين - التوركواز - حجر الكاليه - الشذر.

أماكن تواجده

موطنه الأصلي

بلاد فارس - مصر - العراق - الهند

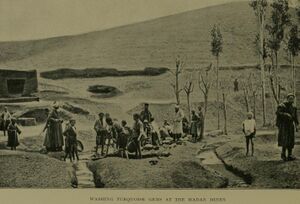

أماكن تواجده حاليا

إيران - مصر - الصين - الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية (كاليفورنيا ,نيفادا وأريزونا) - المكسيك - روسيا - أستراليا - انجلترا - تايلاند - تركستان - تشيلي - سيريلانكا.

تاريخ الحجر

لقد عرف الفيروز في مصر, إذ استعمل فيها منذ عصر النيوليتي وخلال فترة البداري. كما اعتبر بعض المؤرخين أن المصريين القدماء قد اكتشفوا هذا الحجر منذ عصور ما قبل الأسرات, وعصر ما قبل التاريخ. إذ كان يوجد هذا الحجر النفيس في مناجم الفيروز في المغارة بشبه جزيرة سيناء.

ومن محتويات مقبرةتوت عنخ آمون ما يؤكد ولع الفراعنة وملوك الأسرات من قدماء المصريين بالأحجار الكريمة ومن ضمنها حجر الفيروز :

- خاتم من الذهب فصه مكون من الفيروز

- عقاب ناشر جناحيه ومتوج بقرص الشمس من الذهب المرصع بالفيروز, اللازورد والعقيق.

- سوار قابل للإلتواء مؤلف من خرز وجعلان دقيقة الحجم من الذهب والفيروز واللازورد والعقيق, ومشبكه قطعة مسطحة بيضية من الذهب.

واستعمل حجر الفيروز في ترصيع عدد من الخلاخيل التي عثر عليها في مقبرة الملكة حتب حرس من الأسرة الرابعة في الجيزة. كما وجد الفيروز بكثرة في الحلى التي اكتشفت في دهشور من عهد الأسرة الثانية عشر. وتشير الأبحاث التاريخية إلى أن المصريين القدماء هم أول من عرف الفيروز واستخدمه للزينة منذ ثلاثة آلاف عام قبل الميلاد.

التقليد

The Egyptians were the first to produce an artificial imitation of turquoise, in the glazed earthenware product faience. Later glass and enamel were also used, and in modern times more sophisticated porcelain, plastics, and various assembled, pressed, bonded, and sintered products (composed of various copper and aluminium compounds) have been developed: examples of the latter include "Viennese turquoise", made from precipitated aluminium phosphate coloured by copper oleate; and "neolith", a mixture of bayerite and copper(II) phosphate. Most of these products differ markedly from natural turquoise in both physical and chemical properties, but in 1972 Pierre Gilson introduced one fairly close to a true synthetic (it does differ in chemical composition owing to a binder used, meaning it is best described as a simulant rather than a synthetic). Gilson turquoise is made in both a uniform colour and with black "spiderweb matrix" veining not unlike the natural Nevada material.

The most common imitation of turquoise encountered today is dyed howlite and magnesite, both white in their natural states, and the former also having natural (and convincing) black veining similar to that of turquoise. Dyed chalcedony, jasper, and marble is less common, and much less convincing. Other natural materials occasionally confused with or used in lieu of turquoise include: variscite and faustite;[5] chrysocolla (especially when impregnating quartz); lazulite; smithsonite; hemimorphite; wardite; and a fossil bone or tooth called odontolite or "bone turquoise", coloured blue naturally by the mineral vivianite. While rarely encountered today, odontolite was once mined in large quantities—specifically for its use as a substitute for turquoise—in southern France.

These fakes are detected by gemologists using a number of tests, relying primarily on non-destructive, close examination of surface structure under magnification; a featureless, pale blue background peppered by flecks or spots of whitish material is the typical surface appearance of natural turquoise, while manufactured imitations will appear radically different in both colour (usually a uniform dark blue) and texture (usually granular or sugary). Glass and plastic will have a much greater translucency, with bubbles or flow lines often visible just below the surface. Staining between grain boundaries may be visible in dyed imitations.

Some destructive tests may be necessary; for example, the application of diluted hydrochloric acid will cause the carbonates odontolite and magnesite to effervesce and howlite to turn green, while a heated probe may give rise to the pungent smell so indicative of plastic. Differences in specific gravity, refractive index, light absorption (as evident in a material's absorption spectrum), and other physical and optical properties are also considered as means of separation.

المعالجات

Turquoise is treated to enhance both its colour and durability (increased hardness and decreased porosity). As is so often the case with any precious stones, full disclosure about treatment is frequently not given. Gemologists can detect these treatments using a variety of testing methods, some of which are destructive, such as the use of a heated probe applied to an inconspicuous spot, which will reveal oil, wax or plastic treatment.

التشميع والتزييت

Historically, light waxing and oiling were the first treatments used in ancient times, providing a wetting effect, thereby enhancing the colour and lustre. This treatment is more or less acceptable by tradition, especially because treated turquoise is usually of a higher grade to begin with. Oiled and waxed stones are prone to "sweating" under even gentle heat or if exposed to too much sun, and they may develop a white surface film or bloom over time. (With some skill, oil and wax treatments can be restored.)

Backing

Since finer turquoise is often found as thin seams, it may be glued to a base of stronger foreign material for reinforcement. These stones are termed "backed", and it is standard practice that all thinly cut turquoise in the Southwestern United States is backed. Native indigenous peoples of this region, because of their considerable use and wearing of turquoise, have found that backing increases the durability of thinly cut slabs and cabochons of turquoise. They observe that if the stone is not backed it will often crack. Backing of turquoise is not widely known outside of the Native American and Southwestern United States jewellery trade. Backing does not diminish the value of high quality turquoise, and indeed the process is expected for most thinly cut American commercial gemstones.[citation needed]

معالجة زاكري

A proprietary process was created by electrical engineer and turquoise dealer James E. Zachery in the 1980s to improve the stability of medium to high-grade turquoise. The process can be applied in several ways: either through deep penetration on rough turquoise to decrease porosity, by shallow treatment of finished turquoise to enhance color, or both. The treatment can enhance color and improve the turquoise's ability to take a polish. Such treated turquoise can be distinguished in some cases from natural turquoise, without destruction, by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, which can detect its elevated potassium levels. In some instances, such as with already high-quality, low-porosity turquoise that is treated only for porosity, the treatment is undetectable.[6][7]

الصبغ

The use of Prussian blue and other dyes (often in conjunction with bonding treatments) to "enhance” its appearance, make uniform or completely change the colour, is regarded as fraudulent by some purists,[8] especially since some dyes may fade or rub off on the wearer. Dyes have also been used to darken the veins of turquoise.

التثبيت

Material treated with plastic or water glass is termed "bonded" or "stabilized" turquoise. This process consists of pressure impregnation of otherwise unsaleable chalky American material by epoxy and plastics (such as polystyrene) and water glass (sodium silicate) to produce a wetting effect and improve durability. Plastic and water glass treatments are far more permanent and stable than waxing and oiling, and can be applied to material too chemically or physically unstable for oil or wax to provide sufficient improvement. Conversely, stabilization and bonding are rejected by some as too radical an alteration.[8]

The epoxy binding technique was first developed in the 1950s and has been attributed to Colbaugh Processing of Arizona, a company that still operates today.

إعادة التكوين

Perhaps the most extreme of treatments is "reconstitution", wherein fragments of fine turquoise material, too small to be used individually, are powdered and then bonded with resin to form a solid mass. Very often the material sold as "reconstituted turquoise" is artificial, with little or no natural stone, made entirely from resins and dyes. In the trade reconstituted turquoise is often called "block turquoise" or simply "block".

التقييم والعناية

Hardness and richness of colour are two of the major factors in determining the value of turquoise; while colour is a matter of individual taste, generally speaking, the most desirable is a strong sky to robin egg blue (in reference to the eggs of the American robin).[9] Whatever the colour, for many applications, turquoise should not be soft or chalky; even if treated, such lesser material (to which most turquoise belongs) is liable to fade or discolour over time and will not hold up to normal use in jewellery.

The mother rock or matrix in which turquoise is found can often be seen as splotches or a network of brown or black veins running through the stone in a netted pattern;[1] this veining may add value to the stone if the result is complementary, but such a result is uncommon. Such material is sometimes described as "spiderweb matrix"; it is most valued in the Southwest United States and Far East, but is not highly appreciated in the Near East where unblemished and vein-free material is ideal (regardless of how complementary the veining may be). Uniformity of colour is desired, and in finished pieces the quality of workmanship is also a factor; this includes the quality of the polish and the symmetry of the stone. Calibrated stones—that is, stones adhering to standard jewellery setting measurements—may also be more sought after. Like coral and other opaque gems, turquoise is commonly sold at a price according to its physical size in millimetres rather than weight.

Turquoise is treated in many different ways, some more permanent and radical than others. Controversy exists as to whether some of these treatments should be acceptable, but one can be more or less forgiven universally: This is the light waxing or oiling applied to most gem turquoise to improve its colour and lustre; if the material is of high quality to begin with, very little of the wax or oil is absorbed and the turquoise therefore does not rely on this impermanent treatment for its beauty. All other factors being equal, untreated turquoise will always command a higher price. Bonded and reconstituted material is worth considerably less.

Being a phosphate mineral, turquoise is inherently fragile and sensitive to solvents; perfume and other cosmetics will attack the finish and may alter the colour of turquoise gems, as will skin oils, as will most commercial jewellery cleaning fluids. Prolonged exposure to direct sunlight may also discolour or dehydrate turquoise. Care should therefore be taken when wearing such jewels: cosmetics, including sunscreen and hair spray, should be applied before putting on turquoise jewellery, and they should not be worn to a beach or other sun-bathed environment. After use, turquoise should be gently cleaned with a soft cloth to avoid a buildup of residue, and should be stored in its own container to avoid scratching by harder gems. Turquoise can also be adversely affected if stored in an airtight container.[citation needed]

ذكر الفيروز في

الشعر

| فالأرض فيروزج والجو لؤلؤة | والروض ياقوته, والماء بلور |

الإمام علي بن أبي طالب

في علل الشرائع عن عبد الخير ، قال : كان لعلي بن أبي طالب (ع) أربعة خواتيم يتختم بها ياقوت لنبله وفيروزج لنصره والحديد الصيني لقوته وعقيق لحرزه وكان نقش الفيروزج الله الملك الحق. [1]

الإمام الحسين بن علي

من تختم بالفيروزج لم يفتقر كفه. [2]

انظر أيضاً

- Bisbee Blue, with a deep blue color

- Lapis lazuli, with a deep blue color

- Lazurite, with a deep blue color

- List of minerals

- Variscite of pale green color due to trivalent chromium (Cr3+ )

المراجع

- ^ أ ب Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis (1985). Manual of Mineralogy (20th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-80580-9.

- ^ "Turquoise". Mindat.org. Retrieved 2006-10-04.. "Turquoise: Turquoise mineral information and data". Archived from the original on 2006-11-12. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). - ^ Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C., eds. (2000). "Turquoise" (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Vol. IV. Chantilly, Virginia: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 978-0-9622097-3-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-02-11.

- ^ Warr, L. N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةUSGS - ^ Fritsch, Emmanuel; McClure, Shane F.; Ostrooumov, Mikhail; Andres, Yves; Moses, Thomas; Koivula, John I.; Kammerling, Robert C. (Spring 1999). "The identification of Zachery-treated turquoise" (PDF). Gems & Gemology. 35: 4–16. doi:10.5741/GEMS.35.1.4. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Schwarzinger, Bettina; Schwarzinger, Clemens (May 2017). "Investigation of turquoise imitations and treatment with analytical pyrolysis and infrared spectroscopy". Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. 125: 24–31. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2017.05.002.

- ^ أ ب Harriss, Joseph A. "Tantalizing Turquoise". Archived from the original on 2008-02-01. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةdharamsalanet.com

للاستزادة

- British Museum (2000). "Aztec turquoise mosaics". www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved November 15, 2004.

- King, J.C.H., Max Carocci, Caroline Cartwright (2012). Turquoise in Mexico and North America: Science, Conservation, Culture and Collections. British Museum, London, UK.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pogue, J. E. (1915). The Turquoise: A study of its history, mineralogy, geology, ethnology, archaeology, mythology, folklore, and technology. Glorieta, NM: National Academy of Sciences, The Rio Grande Press. ISBN 0-87380-056-7.

- Schadt, H. (1996). Goldsmith's Art: 5000 Years of Jewelry and Hollowware. Stuttgart & New York, NY: Arnoldsche Art Publisher. ISBN 3-925369-54-6.

- Schumann, W. (2000). Gemstones of the World (revised ed.). Sterling Publishing. ISBN 0-8069-9461-4.

- Webster, R. (2000). Gems: Their Sources, Descriptions and Identification (5th ed.). Great Britain: Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 254–263. ISBN 0-7506-1674-1.

وسلات خارجية

Media related to Turquoise (mineral) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Turquoise (mineral) at Wikimedia Commons

- CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using Infobox mineral with unknown parameters

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2007

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2020

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- أحجار كريمة

- Aluminium minerals

- Copper(II) minerals

- Phosphate minerals

- Symbols of New Mexico

- Triclinic minerals

- Symbols of Arizona

- Tetrahydrate minerals

- Minerals in space group 2