توحيد ألمانيا

| الأحداث المؤدية إلى الحرب العالمية الأولى |

|---|

|

|

توحيد ألمانيا Unification of Germany، هي عملية اتحاد مجموعة من الولايات في إطار دولة قومية تمت رسميا في 18 يناير 1871 في قاعة المرايا بقصر ڤرساي في فرنسا بدفع من رئيس الوزراء الألماني آنذاك اوتو فون بسمارك. توافد أمراء الولايات الألمانية على القصر ليعلنوا ڤيلهلم الأول ملك پروسيا إمبراطور الإمبراطورية الألمانية بعد استسلام فرنسا في الحرب الپروسية الفرنسية. يمثل توحيد ألمانيا في 1871 لحظة واحدة فقط في عمليات التوحيد التي شهدتها الولايات الألمانية فيما بينها والتي دامت أكثر من قرن قبل الإعلان الرسمي في 1871 بسبب الفوارق الدينية واللغوية والثقافية بين سكان البلاد الفدرالية الجديدة.

انتهت الإمبراطورية الرومانية المقدسة للأمة الجرمانية من الوجود حينما تنازل الإمبراطور فرانسيس الثاني عن العرش (6 أغسطس 1806) خلال الحروب الناپوليونية. على الرغم من التشتت القانوني والإداري والسياسي الذي عقب نهاية الإمبراطورية، تشارك سكان المناطق الناطقة باللغة الألمانية من الإمبراطورية القديمة في تقاليد لغوية وثقافية وقانونية ازدادت خلال خبرتهم المشتركة في حروب الثورة الفرنسية والحروب النابوليونية. وفرت الليبرالية الأوروبية أساسا فكريا للتوحيد عبر تحدي الأنظمة السلالية والمطلقة للتنظيم الاجتماعي والسياسي وركز فرعها الألماني على أهمية التقاليد والتربية والوحدة اللغوية بين سكان منطقة جغرافية. أما اقتصاديا، أدى التسولفـِراين البروسي (الاتحاد الجمركي الألماني) في 1818 وتوسعه اللاحق ليشمل ولايات أخرى من الاتحاد الألماني إلى تقليص التنافس بين وداخل هذه الولايات. سهلت أنظمة النقل الناشئة ممارسة الأعمال التجارية والسفر الترفيهي وقادت إلى تحقيق التواصل -وفي بعض الأحيان النزاع- بين الناطقين بالألمانية في جميع أنحاء أوروبا الوسطى.

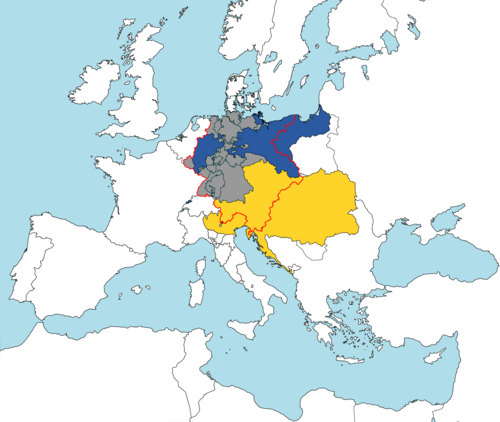

قوـّى نموذج مناطق النفوذ الدبلوماسية الناتج عن مؤتمر ڤيينا في 1814-1815 عقب الحروب الناپوليونية شوكة الإمبراطورية النمساوية وسيطرتها على أوروبا الوسطى. لكن المفاوضات التي جرت في فيينا لم تأخذ في الحسبان القوة النامية بين الولايات الألمانية التي هي بروسيا وفشلت في التوقع بتحدي بروسيا للنمسا في زعامة الولايات الألمانية. فقدمت هذه الازدواجية الألمانية حلين لمشكلة التوحيد الألمانية: Kleindeutsche Lösung (حل ألمانيا الصغرى بدون النمسا) أو Großdeutsche Lösung (حل ألمانيا الكبرى بها النمسا).

يتناقش المؤرخون حول هل كان أوتو فون بسمارك وزير-رئيس پروسيا يملك مخططا لتوسيع الكونفدرالية الألمانية الشمالية لسنة 1866 لتشمل باقي الولايات الألمانية في دولة واحدة أم أنه فقط سعى إلى توسيع نفوذ بروسيا. استنتج المؤرخون أن عدة عوامل بالإضافة إلى قوة سياسة بسمارك الواقعية أدت إلى مجموعة من السياسات المبكرة للاعتراف بالعلاقات السياسية والاقتصادية والعسكرية والدبلوماسية في القرن التاسع عشر. شكل رد فعل الألمان تجاه الوحودية الدنماركية والقومية الفرنسية بؤرة للتعبير عن وحدتهم. وحققت المكاسب العسكرية (خاصة مكاسب بروسيا) في ثلاث حروب جهوية الحماسة والفخر اللذان سخرهما السياسيون لتعزيز الوحدة. استحضرت هذه التجربة ذكريات الإنجاز المتبادل في الحروب النابليونية خاصة في حرب التحرير في 1813-1814. وحـُلت مشكلة الازدواجية، على الأقل مؤقتا، بتوحيد ألمانيا سياسيا وإداريا بدون النمسا في 1871.

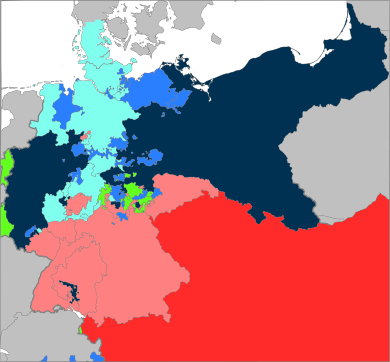

أوروپا الوسطى الناطقة بالألمانية في أوائل القرن 19

قبل 1806، تضمنت أوروبا الوسطى الناطقة بالألمانية أكثر من 300 كيان سياسي أغلبها كان جزءا من الإمبراطورية الرومانية المقدسة أو من توابع دولة الهابسبورگ التوسعية الملكية. تراوحت هذه الكيانات السياسية في الحجم من المتناهية الصغر إلى الصغيرة إلى المتوسطة إلى الكبيرة كمملكتي پروسيا وبافاريا. تنوعت أشكال الحكم في هذه الكيانات وتضمنت المدن الإمبراطورية المستقلة، والتي هي أيضا متنوعة في الحجم، كأوگسبورگ القوية وفيل دير سادت الصغيرة والأراضي الكنسية، والتي بدورها متنوعة النفوذ والحجم، كدير ريشينو الغنية وانتخابية كولونيا القوية والولايات السلالية كڤورتمبرگ. شكلت هذه الأراضي (أو أجزاء منها بالأحرى لأن ملكيات الهابسبورگ وپروسيا الهوهنتسولرن تضمنت مناطق خارج الإمبراطورية) مناطق نفوذ الإمبراطورية الرومانية المقدسة والتي احتوت في بعض الأوقات على أكثر من 1000 كيان. منذ القرن الخامس عشر، مع بعض الاستثناءات، اختار الأمراء الناخبون حكام هابسبورگ المتلاحقين ليحملوا لقب الإمبراطور الروماني المقدس. وفرت آليات الإمبراطورية الرومانية المقدسة الإدارية والقانونية فرصة لحل النزاعات بين الفلاحين وملاك الأراضي والنزاعات بين وداخل السلطات القضائية المتغيرة عبر الولايات الناطقة بالألمانية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك راكم تنظيم الولايات في دوائر إمبراطورية (Reichskreise) الموارد وعزز المصالح الإقليمية والتنظيمية بما فيها التعاون الاقتصادي والحماية العسكرية[1].

نتج عن حرب الائتلاف الثاني (1799-1802) هزيمة قوات الإمبراطورية والائتلاف على يد نابليون بونابرت وإبرام معاهدتي لونيڤيل (1801) وأميان (1802) ونقل تعويض 1803 سيادة عدة مناطق من الإمبراطورية الرومانية المقدسة إلى ممالك سلالية وعلمن الولايات الكنسية واختفت أغلب المدن الإمبراطورية من الخريطة السياسية وغير سكان هذه المناطق الولاء إلى ملوك ودوقات جدد. عززت هذه التغيرات من نفوذ ڤورتمبرگ وبادن. في 1806، بعد غزو ناجح لبروسيا وهزيمة مشتركة لپروسيا وروسيا في معركتي ينا-آورشتت المتزامنتين، فرض نابوليون معاهدة پرسبورگ التي حل بموجبها الإمبراطور الإمبراطورية الرومانية المقدسة[2].

صعود القومية الألمانية تحت النظام الناپليوني

في عهد تفوق الإمبراطورية الفرنسية الأولى (1804-1814)، ازدهرت الحركة القومية الألمانية في الولايات الألمانية الجديدة. ظهرت مبررات مختلفة لتحديد ألمانيا كدولة واحدة ويرجع ذلك جزئيا إلى الخبرة المشتركة (وإن كانت تحت الهيمنة الفرنسية). تمثلت المبررات للفيلسوف الألماني يوهان گوتليب فيخته في أن:

الحدود الأولى والأصلية والطبيعية الحقة للدول هي بدون شك الحدود الداخلية. إن الذين يتحدثون نفس اللغة مربوطون ببعضهم البعض من خلال عدة حبال غير مرئية بشكل طبيعي، وذلك منذ زمن بعيد قبل بداية الفن البشري؛ يفهمون بعضهم البعض ولهم القدرة المستمرة على جعل أنفسهم يتفاهمون أكثر فأكثر؛ ينتمون إلى كيان كامل ويشكلونه وذلك بطبعهم[3].

يمكن للغة المشتركة أن تشكل أساسا للأمة لكن كما لاحظ المؤرخون المعاصرون لألمانيا القرن التاسع عشر، استلزم أمر توحيد عدة مئات من الأنظمة السياسية الحاكمة أكثر من تشابه لغوي[4]. ساهمت تجربة أوروبا الوسطى الناطقة بالألمانية خلال سنوات التفوق الفرنسي في خلق وعي مشترك لطرد الغزاة الفرنسيين واستعادة السيطرة على أراضيها. أثارت احتياجات حملة نابوليون على بولندا (1806-1807) وشبه جزيرة أيبيريا وألمانيا الغربية وغزوه الفاشل لروسيا في 1812 حفيظة الألمان، أمراء وفلاحين بينما خرب حصار نابوليون القاري اقتصاد أوروبا الوسطى. شمل غزو روسيا حوالي 125000 مقاتل من الأراضي الألمانية وشجعت خسارة هذا الجيش الألمان (شماليين وجنوبيين) للتفكير في أوروبا وسطى خالية من نفوذ نابوليون[5]. ولعل خير مثال على ذلك إنشاء ميليشيا التلاميذ المسماة فيلق لوتزوفي الحر[6].

خفف التعثر في روسيا قبضة فرنسا على الأمراء الألمان. في 1813، شن نابوليون حملة على الولايات الألمانية ليعيدهم إلى طاعته؛ بلغت هذه الحرب التي سميت حرب التحرير لاحقا ذروتها في معركة لايبزيغ المعروفة أيضا باسم معركة الأمم. في أكتوبر 1813، قاتل أكثر من 500000 محارب بضرواة على مدى ثلاثة أيام ليجعلوا من هذه المعركة أكبر معركة برية أوروبية في القرن التاسع عشر. نتج عن هذا الصراع انتصار حاسم لائتلاف النمسا وروسيا وبروسيا والسويد وساكسونيا ودفع بالنفوذ الفرنسي شرق الراين. شجع هذا النجاح قوات الائتلاف لملاحقة نابوليون عبر الراين وقضوا على حكومته وجيشه وحبسوه في جزيرة إلبا. خلال فترة استعادة نابوليون لحكمه في 1815 والتي تعرف في التاريخ باسم المائة يوم انتصر الائتلاف السابع المشكل من جيش إنجليزي بالإضافة إلى قوات الائتلاف بقيادة دوق ويلنگتون وجيش بروسي بقيادة گبهارد فون بلوثر في معركة واترلو على جيش نابليون (18 يونيو 1815)[7]. ساعد الدور المحوري لقوات بلوثر على قلب مستوى القتال ضد الفرنسيين خاصة بعد انسحابها من أرض معركة ليني يوما قبل بدأ الأعمال القتالية. لاحق سلاح الفرسان البروسي الجيش الفرنسي المهزوم خلال مساء 18 يونيو ليختموا انتصار الائتلاف. وفر المنظور الألماني لدور قوات بلوثر في معركة واترلو والجهود المشتركة خلال معركة لايبزيغ حماسا وفخرا للشعوب الناطقة بالألمانية[8]. ولعب هذا التأويل دورا أساسيا في تصديق الأسطورة البوروسية التي افتعلها المؤرخون البروسيون القوميون في القرن التاسع عشر[9].

اعادة تنظيم اوروپا المركزية وصعود الإزدواجية الألمانية

بعد هزيمة نابوليون، أقام مؤتمر ڤيينا نظاما أوروبيا سياسيا-دبلوماسيا جديدا يرتكز على توازن القوى. أعاد هذا النظام تنظيم أوروبا ووزعها إلى بواثق نفوذ، والتي في بعض الحالات، قمعت تطلعات بعض القوميات بمن فيهم الألمان والإيطاليون[10].

تشكلت بروسيا المتوسعة وثمان وثلاثون ولاية أخرى من الأراضي المعوضة في 1803 وأصبحت تابعة لمنطقة نفوذ الإمبراطورية النمساوية. أسس المؤتمر اتحادا ألمانيا رخوا (1815-1866) تترأسه النمسا ويتكون من مجلس فدرالي (سمي بوندستاغ (بالألمانية: Bundestag) أو بوندسڤيرزاملونگ (بالألمانية: Bundesversammlung) وكان مجلسا للقادة المعينين) مقره في مدينة فرانكفورت أم ماين. تقديرا للمكانة الإمبراطورية التي تبوأها من قبل الهابسبورگ، أصبح أباطرة النمسا الرؤساء الفخريين لهذا البرلمان. لم يأخذ في الحسبان بناء الهيمنة النمساوية دخول بروسيا في القرن الثامن عشر في السياسة الإمبراطورية. أصبحت قوة بروسيا جلية في حرب الخلافة النمساوية وحرب السنوات السبع[11] دون نسيان المشاكل التي نجمت عن جهود جوزيف الثاني بعد 1760 لموازنة هيمنة بروسيا بهيمنة هابسبورگ متوسعة في حرب الخلافة الباڤارية. استمر جوزيف في البحث عن ريادة الهابسبورگ داخل الإمبراطورية الرومانية المقدسة وواجه فريدريك الثاني ذلك بإنشاء عصبة الأمراء (بالألمانية: Fürstenbund) في 1785. رسخت الازدواجية النمساوية-الپروسية في السياسات الإمبراطورية القديمة. حتى بعد انتهاء الإمبراطورية، أثر هذا التنافس على نمو وتطور الصحوات الوطنية في القرن التاسع عشر[12].

مشكلات اعادة التنظيم

على الرغم من التسمية بوندسڤيرزاملونگ، لا يجب الاعتقاد أنه كان مجلسا شعبيا أي ينتخب من مجموعة ممثلين. لم تكن بعض الولايات تمتلك دساتيرا، مثل دوقية بادن، فاستنادا على متطلبات الاقتراع الصارمة اقتصر الاقتراع على جزء صغير من الساكنة الذكورية[13]. علاوة على ذلك، لم يعكس هذا الحل غير العملي الوضع الجديد لبروسيا في الساحة السياسية. رغم الهزيمة القاسية للجيش البروسي في 1806 في معركتي جينا-أويرستايد، قدم البروسيون وخصوصا سلاح الفرسان أداءا بطوليا في عودة إلى مستواهم المعهود في واترلو. وبناء على ذلك، توقع القادة البروسيون أن تلعب بلادهم دورا محوريا في السياسة الألمانية[14].

تحول تصاعد النزعة القومية الألمانية، محفزا بتجربة الألمان المشتركة في الفترة النابليونية ومرفقا منذ البداية بالليبرالية، إلى علاقات سياسية واجتماعية وثقافية بين الولايات الألمانية[15]. وفي هذا السياق، يمكن استشعار جذور القومية في تجربة الألمان في الفترة النابليونية[16]. ساهمت بورشنشافت ((بالألمانية: Burschenschaft) وهي تنظيمات طلابية يمينية متشبعة بأفكار ليبرالية وقومية) والمظاهرات الشعبية كالتي عقدت في قلعة وارتبرغ في أكتوبر 1817 في تنمية حس الوحدة بين الناطقين بالألمانية في أوروبا الوسطى. زيادة على ذلك، قطع السياسيون وعودا ضمنية وأخرى صريحة خلال حرب التحرير خلفت ترقبا لسيادة شعبية ومشاركة واسعة في إطار العملية السياسية؛ وعود غالبا ما تم الوفاء بها في وقت السلام. أقلق تحرك المنظمات الطلابية القادة المحافظين مثل الأمير كليمنس فينزل ميترنيخ وجعلهم يتخوفون من تصاعد الحس القومي ومن جهة أخرى دفع اغتيال المسرحي الألماني أوغوست فون كوتزيبو في مارس 1819 على يد طالب متطرف وحودي إلى إقرار مراسيم كارلسباد في 20 سبتمبر 1819 التي أعاقت القيادة الفكرية للحركة القومية[17]. تمكن ميترنيخ من إقناع المحافظين على ضرورة تعزيز التشريعات لتقييد الصحافة والحد من تصاعد الحركات الليبرالية والقومية بعد الاغتيال. نتيجة لذلك، قضت هذه المراسيم على البورشنشافت وقلصت عدد الكتب القومية المنشورة ووسعت الرقابة على الصحافة والمراسلات الخاصة وحدت من الخطاب الأكاديمي عبر منع أساتذة الجامعات من الخوض في النقاشات القومية. ناقش يوهان جوزيف غورس المراسيم في كتيبه ألمانيا والثورة ((بالألمانية: Teutschland und die Revolution) و Teutschland هي الاسم القديم لألمانيا (بالألمانية: Deutschland)) (1820) الذي خلص فيه إلى أنه كان من المستحيل وغير المرغوب فيه قمع حرية الرأي العام من خلال تدابير رجعية[18].

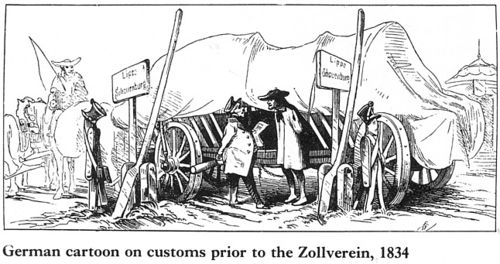

التكامل الاقتصادي: الاتحاد الجمركي

مثل الزولڤراين عاملا آخر لتوحيد الولايات الألمانية وساعد على خلق شعور كبير بالارتباط الاقتصادي. تشكل الزولڤراين في البدء كاتحاد جمركي پروسي في 1818 على يد وزير التمويل البروسي هانز كونت فون بولوف ثم ربط بين الممتلكات الپروسية والهوهنتسولرنية وعلى مر أكثر من ثلاثين سنة انضمت ولايات ألمانية أخرى إلى الاتحاد. أزال الاتحاد الحواجز الحمائية بين الولايات الألمانية خصوصا بتحسين تنقل المواد الخام والسلع المصنوعة وجعل من مرور البضائع سهلا في الحدود ومن ثمن شراء ونقل وبيع المواد الخام أرخص. ظهرت نتائج الاتحاد الجمركي جلية في تطور المراكز الصناعية والتي أغلبها يقع في وديان الراينلاند والسار والرور[19].

الطرق وخطوط السكك الحديدية

في أوائل القرن التاسع عشر، تدهورت الطرق في ألمانيا بشكل مزري. اشتكى المسافرون أجانب ومحليين من حالة هيرشتراسن (بالألمانية: Heerstraßen) وهي الطرق العسكرية التي أنشئت لأجل تنقل القوات. وبما أن الولايات الألمانية لم تعد مفترق طرق عسكرية، تحسنت حالة الطرق وازداد طول الطرق صلبة السطح في بروسيا من 3٬800 كيلومتر (2٬361 ميل) في 1816 و16٬600 كيلومتر (10٬315 ميل) في 1852 خصوصا بعد اختراع الصرار. في عام 1835، كتب هنريك فون غاغرن حول الطرق قائلا أنها "أوردة وشرايين الجسم السياسي..." وتوقع أنها سترفع من مستوى الحرية والاستقلالية والرخاء[21]. بفعل تنقلهم، التقى الناس مع بعضهم على القطارات وفي الفنادق والمطاعم والبعض في المنتجعات العصرية مثل الذي في بادن-بادن. تحسن أيضا النقل البحري. كانت الحواجز على الراين قد أزيلت بأمر من نابوليون وفي عشرينيات القرن التاسع عشر زودت قوارب الأنهار بالمحركات البخارية. وبحلول 1846، بلغ عدد السفن البخارية 180 على الأنهار الألمانية وبحيرة كونستانس وأنهار الدانوب وفيزر وإلبه[22].

لم تكن لتتحقق هذه الإنجازات المهمة دون دور السكك الحديدية. لقب الاقتصادي الألماني فريدريك لست السكك الحديدية والاتحاد الجمركي بالتوأم السيامي مبينا علاقتهما المتبادلة[23]. ولم يكن وحيدا في ذلك فقد كتب الشاعر اوگست هنريك هوفمان فون فالرسليبن قصيدة أشاد فيها بمزايا الزولفيرين وبدأها بقائمة سلع ساهمت في توحيد ألمانيا أكثر من السياسة أو الدبلوماسية[24]. اعتبر مؤرخو الرايخ الثاني السكك الحديدية أول مؤشر على دولة موحدة ومنهم الروائي القومي فيلهلم رابي الذي كتب:"تأسست الإمبراطورية الألمانية عند بناء أول سكة حديد..."[25]. لم يتحمس الجميع لصالح بناء الوحش الحديدي فلم يرى ملك بروسيا فريدريك ويليام الثالث أي نفع من السفر من برلين إلى بوتسدام في وقت أقل أما ميترنيخ فقد رفض الركوب على قطار في حياته. وحذر آخرون من أن تكون السكك الحديدية "شرا" يفسد جمالية الطبيعة ومنهم نيكلوس لينو في قصيدته لسنة 1838 آن دين فخولينغ (وتعني إلى الربيع (بالألمانية: An den Frühling)) التي تحسر فيها على تدمير السكك الحديدية للغابات الألمانية الهادئة[26].

كانت سكة حديد لودڤيگ الباڤارية أول خط شحن وخط ركاب في أراضي ألمانيا وتربط بين نورنبيرغ وفورث في 1835 وبلغت 6 كيلومتر (4 ميل) طولا وتعمل فقط في النهار لكنها كانت مربحة وشعبية. خلا ثلاث سنوات، تم بناء 141 كيلومتر (88 ميل) من السكك الحديدية وبحلول عام 1840 462 كيلومتر (287 ميل) وفي 1860 أصبحت 11٬157 كيلومتر (6٬933 ميل). لم يكن هناك مركز للسكك الحديدية بحكم تعدد الولايات فتوسع السكك على شكل شبكات وربطت المدن والأسواق ضمن مناطق والمناطق ضمن مناطق أكبر. وبعد تطور شبكة السكك أصبح ثمن نقل السلع أرخص ففي 1840 بلغ نقل طن 18 بفينينغ لكل كيلومتر أما في 1870 بلغ الثمن خمس بفينينغ. كان تأثير السكك على الاقتصاد فوريا. فعلى سبيل المثال، أمكن نقل المواد الأولية صعودا وهبوطا في حوض الرور دون الحاجة إلى التفريغ وإعادة التحميل. شجعت السكك النشاط الاقتصادي عبر خلق الطلب على السلع وتسهيل التجارة. في 1850، كانت حمولة الشحن البحري الداخلي تعادل ثلاثة أضعاف حمولة الشحن في القطارات وبحلول علم 1870 انقلبت الكفة لتصبح حمولة الشحن في القطارات معادلة لأربعة أضعاف حمولة الشحن البحري الداخلي. بدلت السكك الحديدية شكل المدن وطريقة سفر الناس وبلغ تأثيرها جميع الطبقات الاجتماعية: من الأغنى إلى الأفقر. حتى لو أن بعض المناطق الحدودية والبعيدة عن وسط ألمانيا لم تربط بالسكك حتى 1890 كان أغلب الساكنة وأهم المراكز الصناعية والإنتاجية مربوطا بخطوط القطارات في 1865[27].

الجغرافيا، حب الوطن واللغة

حينما أصبح السفر أسهل وأسرع وأقل كلفة، بدأ الألمان يرون عوامل أخرى تدعو إلى التوحيد غير اللغة. جمع الأخوان گريم، اللذان كانا السبب وراء صدور معجم غريم للغة الألمانية، العديد من القصص الشعبية الألمانية وأبرزا الاختلاف في الرواية بين مختلف المناطق[28]. كتب كارل بايديكر كـُتب دليل لمختلف المدن والمناطق في أوروبا الوسطى مبينا أماكن للإقامة وأخرى للزيارة ومبرزا قصص قصيرة للقلاع وميادين المعارك والمباني المعروفة والناس المشهورين. تضمنت كتبه أيضا المسافات والطرق التي يجب تجنبها والأخرى التي يجب اتباعها[29].

عبرت كلمات اوگست هنريك هوفمان فون فالرسليبن عن وحدة الشعب الألماني لغويا كما جغرافيا. في ألمانيا ألمانيا فوق كل شيء (بالألمانية: Deutschland Deutschland über Alles) المدعو رسميا نشيد الألمان (بالألمانية: Das Lied der Deutschen)، دعا فالرسليبن حكام الولايات الألمانية إلى الإقرار بالخصائص الموحدة للشعب الألماني[30]. كما ركزت أغاني قومية أخرى كأغنية المراقبة على الراين (بالألمانية: Die Wacht am Rhein) لماكس شنيكنبورگر على الفضاء الجغرافية عوض على اللغة الموحدة. كتب شنيكنبورگر المراقبة على الراين كردة فعل وطنية لمحاولات فرنسا جعل نهر الراين حدها الطبيعي الشرقي. في البيت الشعري وطن أسلافي العزيز، وطن أسلافي العزيز، اتخذ لك استراحة/ فهناك مراقبة على الراين وقصائد أخرى في الشعر القومي مثل أغنية الراين (بالألمانية: Das Rheinlied) لنيكلوس لينو دعا الشعراء الألمان إلى الدفاع عن وطنهم. في 1807، ادعى ألكسندر فون هومبولت أن الطابع الوطني يعكس التأثير الجغرافي الذي يربط الطبيعة بالناس. وبالتزامن مع هذه الأفكار، تطورت الحركات الداعية إلى المحافظة على القلاع القديمة والمواقع التاريخية وخصوصا في منطقة الراينلاند التي شهدت الكثير مع المواجهات مع فرنسا وإسبانيا[31].

ڤورمارز وليبرالية القرن 19

أصبحت فترة الدولة البوليسية في النمسا وبروسيا والرقابة الكبيرة قبل ثورات 1848 في ألمانيا تعرف لاحقا باسم فورمارز أو ما قبل مارس (بالألمانية: Vormärz) في إشارة إلى شهر مارس في سنة 1848. خلال هذه الفترة، تزايد نشاط الليبرالية الأوروبية وتضمنت أجندتها القضايا الاقتصادية والسياسية والاجتماعية. رأى معظم الليبراليين الأوروبيين في ما قبل مارس التوحيد بمبادئ وطنية وشجعوا على التحول إلى الرأسمالية وسعوا نحو تحقيق حق التصويت للذكور وقضايا أخرى. اعتمدت حسهم الراديكالي على تعريف حق الاقتراع: وحق الاقتراع للذكور كان تعريفهم[32].

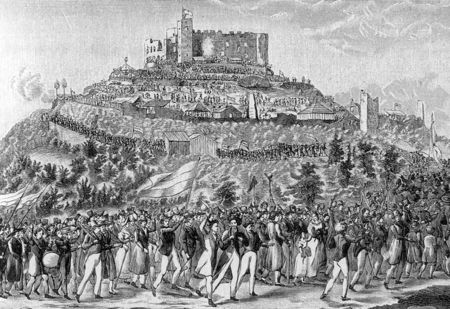

مهرجان هامباخ: القومية الليبرالية والاستجابة المحافظة

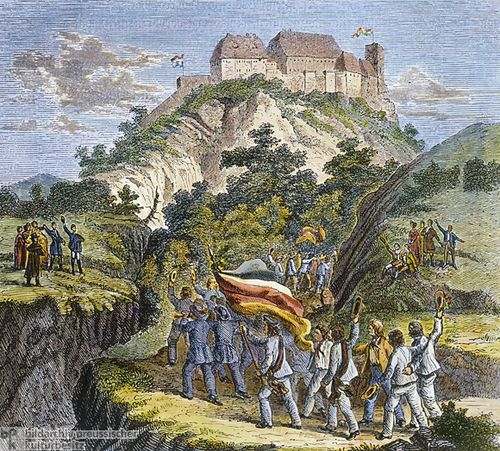

ارتبطت أفكار التوحيد بمبادئ السيادة الشعبية في الأراضي الناطقة بالألمانية رغم ردود فعل المحافظين الواضحة. ارتاد مهرجان هامباخ في مايو 1832 ما يزيد عن 30000 شخص[33]. أصبح المهرجان فيما بعد معرضا للمقاطعة [34] حيث يتوافد المشاركون فيه للاحتفال بمبادئ الأخوة والحرية والوحدة الوطنية. يجتمع المشاركون في بلدة هامباخ ثم يسيرون نحو أنقاض قلعة هامباخ الواقعة أعلى البلدة في مقاطعة بالاتينات البافارية حاملين الأعلام وقارعين الطبول وهم يغنون. كان المشاركون يمشون من بداية النهار حتى منتصفه ليصلوا إلى الأنقاض حيث يستمعون إلى خطب القوميين من محافظين وراديكاليين. اقترحت الخطب في محتواها اختلافا أساسيا بين الحركة القومية الألمانية في ثلاثينيات القرن التاسع عشر والحركة القومية الفرنسية في ثورة يوليو: كان هم القوميين الألمان تعليم الشعب وحين سيتعلم الشعب ماذا يحتاج إليه أو ينقصه، سيحققه. شددت بلاغة وفصاحة خطباء همباخ على الطابع العام السلمي للحركة القومية الألمانية: الهدف لم يكن بناء حواجز، الشكل الفرنسي للقومية، بل مد جسور عاطفية بين المجموعات[35].

استخدم ميترنيخ، كما استخدم جريمة اغتيال كوتزيبو في 1819، المسيرات الشعبية في هامباخ ذريعة ليمرر سياسات اجتماعية محافظة. أكدت "المواد الستة" ل 28 يونيو 1832 أوليا مبدأ السلطة الملكية. في 5 يوليو صوت برلمان فرانكفورت على عشرة مواد إضافية أكدت القوانين القائمة حول الرقابة وقيدت المنظمات السياسية وحدت من أي نشاط شعبي آخر. زيادة على ذلك، وافقت الولايات الأعضاء على إرسال مساعدة عسكرية إلى أي حكومة من بينها مهددة باضطرابات[36]. قاد الأمير فريد نصف الجيش البافاري نحو بالاتينات لقمع المقاطعة. اعتقل العديد من خطباء هامباخ التعساء وحوكموا وسجنوا وأرسل أحدهم، وهو كارل هينريخ بروغمان (1810-1887) طالب قانون وممثل لمنظمة بورشنشافت السرية، إلى بروسيا حيث حكم عليه أوليا بالإعدام ثم أعفي عنه[33].

الليبرالية والاستجابة للمشكلات الاقتصادية

عقدت عدة عوامل أخرى من توسع الحركة القومية في الولايات الألمانية. تشكلت العوامل البشرية في التنافسات السياسية بين أعضاء الكونفدرالية الألمانية خاصة بين النمساويين والبروسيين والتنافس الاجتماعي الاقتصادي بين مصالح التجار وبين ملاك الأراضي القدامى والطبقة الأرسطقراطية. تضمنت العوامل الطبيعية الجفاف الواسع في ثلاثينيات وأربعينيات القرن التاسع عشر وأزمة الغذاء في الأربعينيات. ظهرت تعقيدات أخرى تمثلت في نتائج تناوب التصنيع والمكننة حيث بحث الناس عن فرصة عمل فغادروا بلداتهم وقراهم الصغيرة للعمل خلال الأسبوع في المدن ثم العودة في نهاية الأسبوع ليوم ونصف[37].

ساهم كل من التشويش الاقتصادي والاجتماعي والثقافي لعامة الشعب والصعوبات الاقتصادية التي يمر بها اقتصاد في تحول وضغط الكوارث الطبيعية في تصاعد المشاكل في أوروبا الوسطى[38]. شجع فشل أغلب الحكومات المتتالية في التعامل مع أزمة الغذاء في أربعينيات القرن التاسع عشر الذي سببته لفحة البطاطس المتأخرة (متعلقة بالمجاعة الأيرلندية الكبرى) وتعدد المواسم سيئة الطقس، العديد في التفكير أن الأغنياء والسلطة لا تهتمان بمشاكله. أصبحت الطبقة الحاكمة تهتم أكثر بالاضطرابات المتصاعدة والهياج السياسي والاجتماعي في أوساط الطبقة العاملة وسخط النخبة المثقفة. لم يستطع ازدياد الرقابة والغرامات والحبس والنفي خفض الانتقادات. علاوة عن ذلك، أصبح واضحا أن كل من النمسا وبروسيا تودان قيادة وتزعم أي توحيد ألماني مرتقب وكل واحدة منهما تسعى لكبح مساعي الأخرى لتحقيق التوحيد[39].

التأثيرات الأولى للتوحيد

افتقدت كل من مظاهرة وارتبرگ في 1817 ومهرجان هامباخ في 1832، للأسف، إلى أي برنامج واضح للتوحيد. في هامباخ، عرضت مواقف الخطباء المتعددين برامج متباينة. كان القاسم المشترك الوحيد بينهم هو فكرة التوحيد ولم تتضمن نواياهم خططا معينة حول كيفية تحقيق هذا التوحيد بل مجرد فكرة غامضة تتمثل في أنه إذا كان الفولك (تعني الشعب (بالألمانية: Volk)) متعلما بشكل جيد وواعيا فسيحقق لنفسه ولوحده التوحيد. ولا تعني خطب فضفاضة وأعلام وطلاب مندفعون ووجبات غذاء في نزهات جهازا سياسيا وإداريا وبيروقراطيا جديدا. وللإضافة فقط، لا تظهر الدساتير من عدم لذلك كثر في ذلك الوقت الحديث عن الدساتير. وبالفعل، فكر القوميون في حل لهذا المشكل في 1848[40].

الثورات الألمانية عام 1848 وبرلمان فرانكفورت

هدفت ثورات 1848-1849 المتفرقة في ألمانيا تحقيق التوحيد ودستورا ألمانيا موحدا. ضغط الثوار على حكومات عدة ولايات، وخصوصا في الراينلاند، لتأسيس مجمع تمثيلي (أو برلمان) سيكون من اختصاصه سن دستور. أساسا، عقد الثوار اليساريون آمال حول إمكانية إقرار حق الاقتراع للذكور في الدستور واستحداث برلمان وطني وتحقيق ألمانيا موحدة وكان المرشح الأبرز لقيادتها هو ملك بروسيا وتتمثل الأسباب في ذلك في أن بروسيا كانت أكبر الولايات مساحة وأقواها. أما الثوار من يمين الوسط فسعوا نحو توسيع حق الاقتراع في ولاياتهم ومبدئيا تحقيق شكل رخو من التوحيد. نتج عن هذه الضغوطات عدة انتخابات، مبنية على أنماط مختلفة من شروط الاقتراع، مثل حق الاقتراع ثلاثي الدرجات البروسي والذي منح لبعض المجموعات الانتخابية والمتمثلة في الأثرياء وملاك الأراضي سلطة تمثيلية واسعة[41].

في أبريل 1849، منح برلمان فرانكفورت لقب قيصر (أو إمبراطور (بالألمانية: Kaiser)) لملك بروسيا، فريدريك فيلهم الرابع. رفض الملك اللقب لعدة أسباب كان الرسمي منها أنه لن يقبل تاجا دون موافقة الولايات التي سيحكمها وعنى بذلك حكام تلك الولايات. أما السبب الخفي كان خوفه من معارضة أمراء الولايات الأخرى ومن تدخل عسكري روسي أو نمساوي كما أنه لم يرض بفكرة تقبل تاج سيمنحه له برلمان منتخب شعبيا وقال: لن أقبل تاجا من طين[43]. رغم متطلبات وشروط حق الاقتراع ثلاثي الدرجات والتي فاقمت مشاكل السيادة والمشاركة السياسية والتي حاول الليبراليون التغلب عليها، فقد حقق برلمان فرانكفورت عدة مكاسب أهمها سن الدستور والتوصل إلى حل ألمانيا الصغرى (بالألمانية: kleindeutsch) للمسألة الألمانية. فشل البرلمان في تحقيق الهدف الأكبر وهو التوحيد لكن فشله كان جزئيا فقد عمل الليبراليون على عدة مواضيع دستورية وإصلاحات مشتركة بين الأمراء الألمان[44].

تنامي قوة پروسيا: الواقعية السياسية

King Frederick William IV suffered a stroke in 1857 and could no longer rule. This led to his brother William becoming prince regent of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1858. Meanwhile, Helmuth von Moltke had become chief of the Prussian General Staff in 1857, and Albrecht von Roon would become Prussian Minister of War in 1859.[45] This shuffling of authority within the Prussian military establishment would have important consequences. Von Roon and William (who took an active interest in military structures) began reorganizing the Prussian army, while Moltke redesigned the strategic defense of Prussia by streamlining operational command. Prussian army reforms (especially how to pay for them) caused a constitutional crisis beginning in 1860 because both parliament and William—via his minister of war—wanted control over the military budget. William, crowned King Wilhelm I in 1861, appointed Otto von Bismarck to the position of Minister-President of Prussia in 1862. Bismarck resolved the crisis in favor of the war minister.[46]

The Crimean War of 1854–55 and the Italian War of 1859 disrupted relations among Great Britain, France, Austria, and Russia. In the aftermath of this disarray, the convergence of von Moltke's operational redesign, von Roon and Wilhelm's army restructure, and Bismarck's diplomacy influenced the realignment of the European balance of power. Their combined agendas established Prussia as the leading German power through a combination of foreign diplomatic triumphs—backed up by the possible use of Prussian military might—and an internal conservatism tempered by pragmatism, which came to be known as Realpolitik.[47]

Bismarck expressed the essence of Realpolitik in his subsequently famous "Blood and Iron" speech to the Budget Committee of the Prussian Chamber of Deputies on 30 September 1862, shortly after he became Minister President: "The great questions of the time will not be resolved by speeches and majority decisions—that was the great mistake of 1848 and 1849—but by iron and blood."[48] Bismarck's words, "iron and blood" (or "blood and iron", as often attributed), have often been misappropriated as evidence of a German lust for blood and power.[49] First, the phrase from his speech "the great questions of time will not be resolved by speeches and majority decisions" is often interpreted as a repudiation of the political process—a repudiation Bismarck did not himself advocate.[أ] Second, his emphasis on blood and iron did not imply simply the unrivaled military might of the Prussian army but rather two important aspects: the ability of the assorted German states to produce iron and other related war materials and the willingness to use those war materials if necessary.[51]

By 1862, when Bismarck made his speech, the idea of a German nation-state in the peaceful spirit of Pan-Germanism had shifted from the liberal and democratic character of 1848 to accommodate Bismarck's more conservative Realpolitik. Bismarck sought to link a unified state to the Hohenzollern dynasty, which for some historians remains one of Bismarck's primary contributions to the creation of the German Empire in 1871.[52] While the conditions of the treaties binding the various German states to one another prohibited Bismarck from taking unilateral action, the politician and diplomat in him realized the impracticality of this.[53] To get the German states to unify, Bismarck needed a single, outside enemy that would declare war on one of the German states first, thus providing a casus belli to rally all Germans behind. This opportunity arose with the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. Historians have long debated Bismarck's role in the events leading up to the war. The traditional view, promulgated in large part by late 19th- and early 20th-century pro-Prussian historians, maintains that Bismarck's intent was always German unification. Post-1945 historians, however, see more short-term opportunism and cynicism in Bismarck's manipulation of the circumstances to create a war, rather than a grand scheme to unify a nation-state.[54] Regardless of motivation, by manipulating events of 1866 and 1870, Bismarck demonstrated the political and diplomatic skill that had caused Wilhelm to turn to him in 1862.[55]

Three episodes proved fundamental to the unification of Germany. First, the death without male heirs of Frederick VII of Denmark led to the Second War of Schleswig in 1864. Second, the unification of Italy provided Prussia an ally against Austria in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. Finally, France—fearing Hohenzollern encirclement—declared war on Prussia in 1870, resulting in the Franco-Prussian War. Through a combination of Bismarck's diplomacy and political leadership, von Roon's military reorganization, and von Moltke's military strategy, Prussia demonstrated that none of the European signatories of the 1815 peace treaty could guarantee Austria's sphere of influence in Central Europe, thus achieving Prussian hegemony in Germany and ending the dualism debate.[56]

مسألة شلسڤيگ-هولشتاين

The first episode in the saga of German unification under Bismarck came with the Schleswig-Holstein Question. On 15 November 1863, Christian IX became king of Denmark and duke of Schleswig, Holstein, and Lauenburg, which the Danish king held in personal union. On 18 November 1863, he signed the Danish November Constitution which replaced The Law of Sjælland and The Law of Jutland, which meant the new constitution applied to the Duchy of Schleswig. The German Confederation saw this act as a violation of the London Protocol of 1852, which emphasized the status of the Kingdom of Denmark as distinct from the three independent duchies. The German Confederation could use the ethnicities of the area as a rallying cry: Holstein and Lauenburg were largely of German origin and spoke German in everyday life, while Schleswig had a significant Danish population and history. Diplomatic attempts to have the November Constitution repealed collapsed, and fighting began when Prussian and Austrian troops crossed the Eider river on 1 February 1864.[citation needed]

Initially, the Danes attempted to defend their country using an ancient earthen wall known as the Danevirke, but this proved futile. The Danes were no match for the combined Prussian and Austrian forces and their modern armaments. The needle gun, one of the first bolt action rifles to be used in conflict, aided the Prussians in both this war and the Austro-Prussian War two years later. The rifle enabled a Prussian soldier to fire five shots while lying prone, while its muzzle-loading counterpart could only fire one shot and had to be reloaded while standing. The Second Schleswig War resulted in victory for the combined armies of Prussia and Austria, and the two countries won control of Schleswig and Holstein in the concluding peace of Vienna, signed on 30 October 1864.[57]

الحرب بين پروسيا والنمسا 1866

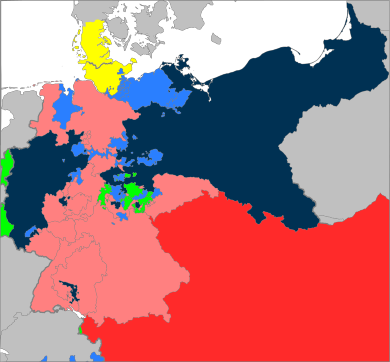

The second episode in Bismarck's unification efforts occurred in 1866. In concert with the newly formed Italy, Bismarck created a diplomatic environment in which Austria declared war on Prussia. The dramatic prelude to the war occurred largely in Frankfurt, where the two powers claimed to speak for all the German states in the parliament. In April 1866, the Prussian representative in Florence signed a secret agreement with the Italian government, committing each state to assist the other in a war against Austria. The next day, the Prussian delegate to the Frankfurt assembly presented a plan calling for a national constitution, a directly elected national Diet, and universal suffrage. German liberals were justifiably skeptical of this plan, having witnessed Bismarck's difficult and ambiguous relationship with the Prussian Landtag (State Parliament), a relationship characterized by Bismarck's cajoling and riding roughshod over the representatives. These skeptics saw the proposal as a ploy to enhance Prussian power rather than a progressive agenda of reform.[58]

اختيار طرف

The debate over the proposed national constitution became moot when news of Italian troop movements in Tyrol and near the Venetian border reached Vienna in April 1866. The Austrian government ordered partial mobilization in the southern regions; the Italians responded by ordering full mobilization. Despite calls for rational thought and action, Italy, Prussia, and Austria continued to rush toward armed conflict. On 1 May, Wilhelm gave von Moltke command over the Prussian armed forces, and the next day he began full-scale mobilization.[59]

In the Diet, the group of middle-sized states, known as Mittelstaaten (Bavaria, Württemberg, the grand duchies of Baden and Hesse, and the duchies of Saxony–Weimar, Saxony–Meiningen, Saxony–Coburg, and Nassau), supported complete demobilization within the Confederation. These individual governments rejected the potent combination of enticing promises and subtle (or outright) threats Bismarck used to try to gain their support against the Habsburgs. The Prussian war cabinet understood that its only supporters among the German states against the Habsburgs were two small principalities bordering on Brandenburg that had little military strength or political clout: the Grand Duchies of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Strelitz. They also understood that Prussia's only ally abroad was Italy.[60]

Opposition to Prussia's strong-armed tactics surfaced in other social and political groups. Throughout the German states, city councils, liberal parliamentary members who favored a unified state, and chambers of commerce—which would see great benefits from unification—opposed any war between Prussia and Austria. They believed any such conflict would only serve the interests of royal dynasties. Their own interests, which they understood as "civil" or "bourgeois", seemed irrelevant. Public opinion also opposed Prussian domination. Catholic populations along the Rhine—especially in such cosmopolitan regions as Cologne and in the heavily populated Ruhr Valley—continued to support Austria. By late spring, most important states opposed Berlin's effort to reorganize the German states by force. The Prussian cabinet saw German unity as an issue of power and a question of who had the strength and will to wield that power. Meanwhile, the liberals in the Frankfurt assembly saw German unity as a process of negotiation that would lead to the distribution of power among the many parties.[61]

انعزال النمسا

Although several German states initially sided with Austria, they stayed on the defensive and failed to take effective initiatives against Prussian troops. The Austrian army therefore faced the technologically superior Prussian army with support only from Saxony. France promised aid, but it came late and was insufficient.[62] Complicating the situation for Austria, the Italian mobilization on Austria's southern border required a diversion of forces away from battle with Prussia to fight the Third Italian War of Independence on a second front in Venetia and on the Adriatic sea.[63]

A quick peace was essential to keep Russia from entering the conflict on Austria's side.[64] In the day-long Battle of Königgrätz, near the village of Sadová, Friedrich Carl and his troops arrived late, and in the wrong place. Once he arrived, however, he ordered his troops immediately into the fray. The battle was a decisive victory for Prussia and forced the Habsburgs to end the war with the unfavorable Peace of Prague,[65] laying the groundwork for the Kleindeutschland (little Germany) solution, or "Germany without Austria."

تأسيس دولة موحدة

There is, in political geography, no Germany proper to speak of. There are Kingdoms and Grand Duchies, and Duchies and Principalities, inhabited by Germans, and each [is] separately ruled by an independent sovereign with all the machinery of State. Yet there is a natural undercurrent tending to a national feeling and toward a union of the Germans into one great nation, ruled by one common head as a national unit.

— article from The New York Times published on July 1, 1866[66]

سلام پراگ وكونفدرالية ألمانيا الشمالية

The Peace of Prague sealed the dissolution of the German Confederation. Its former leading state, the Austrian Empire, was along with the majority of its allies excluded from the ensuing North German Confederation Treaty sponsored by Prussia which directly annexed Hanover, Hesse-Kassel, Nassau, and the city of Frankfurt, while Hesse Darmstadt lost some territory but kept its statehood. At the same time, the original East Prussian cradle of the Prussian statehood as well as the Prussian-held Polish- or Kashubian-speaking territories of Province of Posen and West Prussia were formally annexed into the North German Confederation, thus Germany. Following adoption of the North German Constitution, the new state obtained its own constitution, flag, and governmental and administrative structures.[citation needed]

Through military victory, Prussia under Bismarck's influence had overcome Austria's active resistance to the idea of a unified Germany. The states south of the Main River (Baden, Württemberg, and Bavaria) signed separate treaties requiring them to pay indemnities and to form alliances bringing them into Prussia's sphere of influence.[67] Austria's influence over the German states may have been broken, but the war also splintered the spirit of pan-German unity, as many German states resented Prussian power politics.[68]

إيطاليا الموحدة والتسوية المجرية-النمساوية

The Peace of Prague offered lenient terms to Austria but its relationship with the new nation-state of Italy underwent major restructuring. Although the Austrians were far more successful in the military field against Italian troops, the monarchy lost the important province of Venetia. The Habsburgs ceded Venetia to France, which then formally transferred control to Italy.[69]

The end of Austrian dominance of the German states shifted Austria's attention to the Balkans. The reality of defeat for Austria also caused a reevaluation of internal divisions, local autonomy, and liberalism.[70] In 1867, the Austrian emperor Franz Joseph accepted a settlement (the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867) in which he gave his Hungarian holdings equal status with his Austrian domains, creating the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary.[71]

الحرب مع فرنسا

The French public resented the Prussian victory and demanded Revanche pour Sadová ("Revenge for Sadova"), illustrating anti-Prussian sentiment in France—a problem that would accelerate in the months leading up to the Franco-Prussian War.[72] The Austro-Prussian War also damaged relations with the French government. At a meeting in Biarritz in September 1865 with Napoleon III, Bismarck had let it be understood (or Napoleon had thought he understood) that France might annex parts of Belgium and Luxembourg in exchange for its neutrality in the war. These annexations did not happen, resulting in animosity from Napoleon towards Bismarck.[citation needed]

خلفية

By 1870 three of the important lessons of the Austro-Prussian war had become apparent. The first lesson was that, through force of arms, a powerful state could challenge the old alliances and spheres of influence established in 1815. Second, through diplomatic maneuvering, a skilful leader could create an environment in which a rival state would declare war first, thus forcing states allied with the "victim" of external aggression to come to the leader's aid. Finally, as Prussian military capacity far exceeded that of Austria, Prussia was clearly the only state within the Confederation (or among the German states generally) capable of protecting all of them from potential interference or aggression. In 1866, most mid-sized German states had opposed Prussia, but by 1870 these states had been coerced and coaxed into mutually protective alliances with Prussia. If a European state declared war on one of their members, then they all would come to the defense of the attacked state. With skilful manipulation of European politics, Bismarck created a situation in which France would play the role of aggressor in German affairs, while Prussia would play that of the protector of German rights and liberties.[73]

At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Metternich and his conservative allies had reestablished the Spanish monarchy under King Ferdinand VII. Over the following forty years, the great powers supported the Spanish monarchy, but events in 1868 would further test the old system, finally providing the external trigger needed by Bismarck.[citation needed]

دوائر النفوذ تتساقط في إسبانيا

A revolution in Spain overthrew Queen Isabella II, and the throne remained empty while Isabella lived in sumptuous exile in Paris. The Spanish, looking for a suitable Catholic successor, had offered the post to three European princes, each of whom was rejected by Napoleon III, who served as regional power-broker. Finally, in 1870 the Regency offered the crown to Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, a prince of the Catholic cadet Hohenzollern line. The ensuing furor has been dubbed by historians as the Hohenzollern candidature.[74] Over the next few weeks, the Spanish offer turned into the talk of Europe. Bismarck encouraged Leopold to accept the offer.[75] A successful installment of a Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen king in Spain would mean that two countries on either side of France would both have German kings of Hohenzollern descent. This may have been a pleasing prospect for Bismarck, but it was unacceptable to either Napoleon III or to Agenor, duc de Gramont, his minister of foreign affairs. Gramont wrote a sharply formulated ultimatum to Wilhelm, as head of the Hohenzollern family, stating that if any Hohenzollern prince should accept the crown of Spain, the French government would respond—although he left ambiguous the nature of such response. The prince withdrew as a candidate, thus defusing the crisis, but the French ambassador to Berlin would not let the issue lie.[76] He approached the Prussian king directly while Wilhelm was vacationing in Ems Spa, demanding that the King release a statement saying he would never support the installation of a Hohenzollern on the throne of Spain. Wilhelm refused to give such an encompassing statement, and he sent Bismarck a dispatch by telegram describing the French demands. Bismarck used the king's telegram, called the Ems Dispatch, as a template for a short statement to the press. With its wording shortened and sharpened by Bismarck—and further alterations made in the course of its translation by the French agency Havas—the Ems Dispatch raised an angry furor in France. The French public, still aggravated over the defeat at Sadová, demanded war.[77]

اندلاع الكراهية والنهاية الكارثية للإمبراطورية الفرنسية الثانية

Napoleon III had tried to secure territorial concessions from both sides before and after the Austro-Prussian War, but despite his role as mediator during the peace negotiations, he ended up with nothing. He then hoped that Austria would join in a war of revenge and that its former allies—particularly the southern German states of Baden, Württemberg, and Bavaria—would join in the cause. This hope would prove futile since the 1866 treaty came into effect and united all German states militarily—if not happily—to fight against France. Instead of a war of revenge against Prussia, supported by various German allies, France engaged in a war against all of the German states without any allies of its own.[78]

The reorganization of the military by von Roon and the operational strategy of Moltke combined against France to great effect. The speed of Prussian mobilization astonished the French, and the Prussian ability to concentrate power at specific points—reminiscent of Napoleon I's strategies seventy years earlier—overwhelmed French mobilization. Utilizing their efficiently laid rail grid, Prussian troops were delivered to battle areas rested and prepared to fight, whereas French troops had to march for considerable distances to reach combat zones. After a number of battles, notably Spicheren, Wörth, Mars la Tour, and Gravelotte, the Prussians defeated the main French armies and advanced on the primary city of Metz and the French capital of Paris. They captured Napoleon III and took an entire army as prisoners at Sedan on 1 September 1870.[79]

إعلان الإمبراطورية الألمانية

The humiliating capture of the French emperor and the loss of the French army itself, which marched into captivity at a makeshift camp in the Saarland ("Camp Misery"), threw the French government into turmoil; Napoleon's energetic opponents overthrew his government and proclaimed the Third Republic.[80] "In the days after Sedan, Prussian envoys met with the French and demanded a large cash indemnity as well as the cession of Alsace and Lorraine. All parties in France rejected the terms, insisting that any armistice be forged "on the basis of territorial integrity." France, in other words, would pay reparations for starting the war, but would, in Jules Favre's famous phrase, "cede neither a clod of our earth nor a stone of our fortresses".[81] The German High Command expected an overture of peace from the French, but the new republic refused to surrender. The Prussian army invested Paris and held it under siege until mid-January, with the city being "ineffectually bombarded".[82] Nevertheless, in January, the Germans fired some 12,000 shells, 300–400 grenades daily into the city.[83] On January 18, 1871, the German princes and senior military commanders proclaimed Wilhelm "German Emperor" in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles.[84] Under the subsequent Treaty of Frankfurt, France relinquished most of its traditionally German regions (Alsace and the German-speaking part of Lorraine); paid an indemnity, calculated (on the basis of population) as the precise equivalent of the indemnity that Napoleon Bonaparte imposed on Prussia in 1807;[85] and accepted German administration of Paris and most of northern France, with "German troops to be withdrawn stage by stage with each installment of the indemnity payment".[86]

الحرب كتتويج لعملية التوحيد

Victory in the Franco-Prussian War proved the capstone of the unification process. In the first half of the 1860s, Austria and Prussia both contended to speak for the German states; both maintained they could support German interests abroad and protect German interests at home. In responding to the Schleswig-Holstein Question, they both proved equally diligent in doing so. After the victory over Austria in 1866, Prussia began internally asserting its authority to speak for the German states and defend German interests, while Austria began directing more and more of its attention to possessions in the Balkans. The victory over France in 1871 expanded Prussian hegemony in the German states (aside from Austria) to the international level. With the proclamation of Wilhelm as Kaiser, Prussia assumed the leadership of the new empire. The southern states became officially incorporated into a unified Germany at the Treaty of Versailles of 1871 (signed 26 February 1871; later ratified in the Treaty of Frankfurt of 10 May 1871), which formally ended the war.[87] Although Bismarck had led the transformation of Germany from a loose confederation into a federal nation state, he had not done it alone. Unification was achieved by building on a tradition of legal collaboration under the Holy Roman Empire and economic collaboration through the Zollverein. The difficulties of the Vormärz, the impact of the 1848 liberals, the importance of von Roon's military reorganization, and von Moltke's strategic brilliance all played a part in political unification.[88] "Einheit – unity – was achieved at the expense of Freiheit – freedom. The German Empire became," in Karl Marx's words, "a military despotism cloaked in parliamentary forms with a feudal ingredient, influenced by the bourgeoisie, festooned with bureaucrats and guarded by police." Indeed, many historians would see Germany's "escape into war" in 1914 as a flight from all of the internal-political contradictions forged by Bismarck at Versailles in the fall of 1870.[89]

التوحيد السياسي والإداري

The new German Empire included 26 political entities: twenty-five constituent states (or Bundesstaaten) and one Imperial Territory (or Reichsland). It realized the Kleindeutsche Lösung ("Lesser German Solution", with the exclusion of Austria) as opposed to a Großdeutsche Lösung or "Greater German Solution", which would have included Austria. Unifying various states into one nation required more than some military victories, however much these might have boosted morale. It also required a rethinking of political, social, and cultural behaviors and the construction of new metaphors about "us" and "them". Who were the new members of this new nation? What did they stand for? How were they to be organized?[90]

الولايات المكونة للإمبراطورية

Though often characterized as a federation of monarchs, the German Empire, strictly speaking, federated a group of 26 constituent entities with different forms of government, ranging from the main four constitutional monarchies to the three republican Hanseatic cities.[91]

| الولاية | العاصمة | |

|---|---|---|

| الممالك (Königreiche) | ||

| پروسيا (Preußen) | برلين | |

| باڤاريا (Bayern) | ميونخ | |

| ساكسونيا (Sachsen) | درسدن | |

| ڤورتمبرگ | شتوتگارت | |

| الگراندوقيات (Großherzogtümer) | ||

| بادن | كارلسروه | |

| Hesse (Hessen) | دارمشتات | |

| Mecklenburg-Schwerin | Schwerin | |

| Mecklenburg-Strelitz | Neustrelitz | |

| اولدنبورگ | اولدنبورگ | |

| زاكسه-ڤايمار-آيزناخ (Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach) | ڤايمار | |

| الدوقيات (Herzogtümer) | ||

| آنهالت | دساو | |

| برونزويك (Braunschweig) | براونشڤايگ | |

| Saxe-Altenburg (Sachsen-Altenburg) | Altenburg | |

| Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha) | Coburg | |

| Saxe-Meiningen (Sachsen-Meiningen) | Meiningen | |

| الإمارات (Fürstentümer) | ||

| ليپه | دتمولد | |

| Reuss, junior line | گـِرا | |

| Reuss, senior line | Greiz | |

| Schaumburg-Lippe | Bückeburg | |

| Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt | Rudolstadt | |

| Schwarzburg-Sondershausen | Sondershausen | |

| Waldeck-Pyrmont | Arolsen | |

| المدن الهانزية الحرة (Freie Hansestädte) | ||

| برمن | ||

| هامبورگ | ||

| لوبك | ||

| أراضي امبراطورية (Reichsland) | ||

| الألزاس-اللورين (Elsaß-Lothringen) | شتراسبورگ | |

كانت الإمبراطورية، رغم اعتبارها فدرالية ملوك، فدرالية تجمع الولايات[92].

البنية السياسية للإمبراطورية

The 1866 North German Constitution became (with some semantic adjustments) the 1871 Constitution of the German Empire. With this constitution, the new Germany acquired some democratic features: notably the Imperial Diet, which—in contrast to the parliament of Prussia—gave citizens representation on the basis of elections by direct and equal suffrage of all males who had reached the age of 25. Furthermore, elections were generally free of chicanery, engendering pride in the national parliament.[93] However, legislation required the consent of the Bundesrat, the federal council of deputies from the states, in and over which Prussia had a powerful influence; Prussia could appoint 17 of 58 delegates with only 14 votes needed for a veto. Prussia thus exercised influence in both bodies, with executive power vested in the Prussian King as Kaiser, who appointed the federal chancellor. The chancellor was accountable solely to, and served entirely at the discretion of, the Emperor. Officially, the chancellor functioned as a one-man cabinet and was responsible for the conduct of all state affairs; in practice, the State Secretaries (bureaucratic top officials in charge of such fields as finance, war, foreign affairs, etc.) acted as unofficial portfolio ministers. With the exception of the years 1872–1873 and 1892–1894, the imperial chancellor was always simultaneously the prime minister of the imperial dynasty's hegemonic home-kingdom, Prussia. The Imperial Diet had the power to pass, amend, or reject bills, but it could not initiate legislation. (The power of initiating legislation rested with the chancellor.) The other states retained their own governments, but the military forces of the smaller states came under Prussian control. The militaries of the larger states (such as the Kingdoms of Bavaria and Saxony) retained some autonomy, but they underwent major reforms to coordinate with Prussian military principles and came under federal government control in wartime.[94]

الحجج التاريخية والتحليل الاجتماعي للإمبراطورية

The Sonderweg hypothesis attributed Germany's difficult 20th century to the weak political, legal, and economic basis of the new empire. The Prussian landed elites, the Junkers, retained a substantial share of political power in the unified state. The Sonderweg hypothesis attributed their power to the absence of a revolutionary breakthrough by the middle classes, or by peasants in combination with the urban workers, in 1848 and again in 1871. Recent research into the role of the Grand Bourgeoisie—which included bankers, merchants, industrialists, and entrepreneurs—in the construction of the new state has largely refuted the claim of political and economic dominance of the Junkers as a social group. This newer scholarship has demonstrated the importance of the merchant classes of the Hanseatic cities and the industrial leadership (the latter particularly important in the Rhineland) in the ongoing development of the Second Empire.[95]

Additional studies of different groups in Wilhelmine Germany have all contributed to a new view of the period. Although the Junkers did, indeed, continue to control the officer corps, they did not dominate social, political, and economic matters as much as the Sonderweg theorists had hypothesized. Eastern Junker power had a counterweight in the western provinces in the form of the Grand Bourgeoisie and in the growing professional class of bureaucrats, teachers, professors, doctors, lawyers, scientists, etc.[96]

وراء الآلية السياسية: تأسيس الأمة

If the Wartburg and Hambach rallies had lacked a constitution and administrative apparatus, that problem was addressed between 1867 and 1871. Yet, as Germans discovered, grand speeches, flags, and enthusiastic crowds, a constitution, a political reorganization, and the provision of an imperial superstructure; and the revised Customs Union of 1867–68, still did not make a nation.[97]

A key element of the nation-state is the creation of a national culture, frequently—although not necessarily—through deliberate national policy.[98][90] In the new German nation, a Kulturkampf (1872–78) that followed political, economic, and administrative unification attempted to address, with a remarkable lack of success, some of the contradictions in German society. In particular, it involved a struggle over language, education, and religion. A policy of Germanization of non-German people of the empire's population, including the Polish and Danish minorities, started with language, in particular, the German language, compulsory schooling (Germanization), and the attempted creation of standardized curricula for those schools to promote and celebrate the idea of a shared past. Finally, it extended to the religion of the new Empire's population.[99]

كولتوركامپف

كولتوركامپف، مصطلح ألماني (ويعني حرفياً "صراع الثقافات") يشير إلى السياسات الألمانية فيما يتعلق بالعلمانية وتأثير الكنيسة الكاثوليكية الرومانية، والتي أصدرها من 1871 إلى 1878 رئيس وزراء پروسيا، اوتو فون بسمارك. ولم تمتد الكولتوركامپف إلى الدويلات الألمانية الأخرى مثل باڤاريا. وكما يقول أحد الباحثين، "الهجوم على الكنيسة تضمن سلسلة من القوانين التمييزية الپروسية التي جعلت الكاثوليك يشعرون بالاضطهاد في أمة ذات أغلبية پروتستانتية." الجزويت، الفرنسيسكان والدومنيكان والطوائف الأخرى تم طردهم في ذروة هيستريا التي دامت نحو 20 سنة من المواجهات المناهضة للأديرة وللجزويت.[100]

For some Germans, the definition of nation did not include pluralism, and Catholics in particular came under scrutiny; some Germans, and especially Bismarck, feared that the Catholics' connection to the papacy might make them less loyal to the nation. As chancellor, Bismarck tried without much success to limit the influence of the Roman Catholic Church and of its party-political arm, the Catholic Centre Party, in schools and education- and language-related policies. The Catholic Centre Party remained particularly well entrenched in the Catholic strongholds of Bavaria and southern Baden, and in urban areas that held high populations of displaced rural workers seeking jobs in the heavy industry, and sought to protect the rights not only of Catholics, but other minorities, including the Poles, and the French minorities in the Alsatian lands.[101] The May Laws of 1873 brought the appointment of priests, and their education, under the control of the state, resulting in the closure of many seminaries, and a shortage of priests. The Congregations Law of 1875 abolished religious orders, ended state subsidies to the Catholic Church, and removed religious protections from the Prussian constitution.[102]

دمج الجالية اليهودية

The Germanized Jews remained another vulnerable population in the new German nation-state. Since 1780, after emancipation by the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II, Jews in the former Habsburg territories had enjoyed considerable economic and legal privileges that their counterparts in other German-speaking territories did not: they could own land, for example, and they did not have to live in a Jewish quarter (also called the Judengasse, or "Jews' alley"). They could also attend universities and enter the professions. During the Revolutionary and Napoleonic eras, many of the previously strong barriers between Jews and Christians broke down. Napoleon had ordered the emancipation of Jews throughout territories under French hegemony. Like their French counterparts, wealthy German Jews sponsored salons; in particular, several Jewish salonnières held important gatherings in Frankfurt and Berlin during which German intellectuals developed their own form of republican intellectualism. Throughout the subsequent decades, beginning almost immediately after the defeat of the French, reaction against the mixing of Jews and Christians limited the intellectual impact of these salons. Beyond the salons, Jews continued a process of Germanization in which they intentionally adopted German modes of dress and speech, working to insert themselves into the emerging 19th-century German public sphere. The religious reform movement among German Jews reflected this effort.[103]

By the years of unification, German Jews played an important role in the intellectual underpinnings of the German professional, intellectual, and social life. The expulsion of Jews from Russia in the 1880s and 1890s complicated integration into the German public sphere. Russian Jews arrived in north German cities in the thousands; considerably less educated and less affluent, their often dismal poverty dismayed many of the Germanized Jews. Many of the problems related to poverty (such as illness, overcrowded housing, unemployment, school absenteeism, refusal to learn German, etc.) emphasized their distinctiveness for not only the Christian Germans, but for the local Jewish populations as well.[104]

كتابة قصة الأمة

Another important element in nation-building, the story of the heroic past, fell to such nationalist German historians as the liberal constitutionalist Friedrich Dahlmann (1785–1860), his conservative student Heinrich von Treitschke (1834–1896), and others less conservative, such as Theodor Mommsen (1817–1903) and Heinrich von Sybel (1817–1895), to name two. Dahlmann himself died before unification, but he laid the groundwork for the nationalist histories to come through his histories of the English and French revolutions, by casting these revolutions as fundamental to the construction of a nation, and Dahlmann himself viewed Prussia as the logical agent of unification.[105]

Heinrich von Treitschke's History of Germany in the Nineteenth Century, published in 1879, has perhaps a misleading title: it privileges the history of Prussia over the history of other German states, and it tells the story of the German-speaking peoples through the guise of Prussia's destiny to unite all German states under its leadership. The creation of this Borussian myth (Borussia is the Latin name for Prussia) established Prussia as Germany's savior; it was the destiny of all Germans to be united, this myth maintains, and it was Prussia's destiny to accomplish this.[106] According to this story, Prussia played the dominant role in bringing the German states together as a nation-state; only Prussia could protect German liberties from being crushed by French or Russian influence. The story continues by drawing on Prussia's role in saving Germans from the resurgence of Napoleon's power in 1815, at Waterloo, creating some semblance of economic unity, and uniting Germans under one proud flag after 1871.[ب]

Mommsen's contributions to the Monumenta Germaniae Historica laid the groundwork for additional scholarship on the study of the German nation, expanding the notion of "Germany" to mean other areas beyond Prussia. A liberal professor, historian, and theologian, and generally a titan among late 19th-century scholars, Mommsen served as a delegate to the Prussian House of Representatives from 1863 to 1866 and 1873 to 1879; he also served as a delegate to the Reichstag from 1881 to 1884, for the liberal German Progress Party (Deutsche Fortschrittspartei) and later for the National Liberal Party. He opposed the antisemitic programs of Bismarck's Kulturkampf and the vitriolic text that Treitschke often employed in the publication of his Studien über die Judenfrage (Studies of the Jewish Question), which encouraged assimilation and Germanization of Jews.[108]

انظر أيضاً

- توحيد إيطاليا

- Formation of Romania

- Reichsbürgerbewegung

- Pan-Germanism

- Qin's wars of Chinese unification

كتاب قصة الأمة

ملاحظات

- ^ Bismarck had "cut his teeth" on German politics, and German politicians, in Frankfurt: a quintessential politician, Bismarck had built his power-base by absorbing and co-opting measures from throughout the political spectrum. He was first and foremost a politician, and in this lied his strength. Furthermore, since he trusted neither Moltke nor Roon, he was reluctant to enter a military enterprise over which he would have no control.[50]

- ^ Many modern historians describe this myth, without subscribing to it.[صفحة مطلوبة][107]

المصادر

هوامش

- ^ أنظر على سبيل المثال The Swabian Kreis: Institutional Growth in the Holy Roman Empire 1648–1715. المجلد 3 لجيمس ألان فان وهي دراسة مقدمة للجنة الدولية لتأريخ المؤسسات التمثيلية والبرلمانية ببروكسيل 1975. وGerman home towns: community, state, and general estate, 1648–1871 لمارك والكر (إيثاكا 1998).

- ^ Robert A. Kann. History of the Habsburg Empire: 1526–1918,Los Angeles, 1974, p. 221. عند تنازله قام فرانسيس بتحرير الولايات السابقة من واجباتها ومهامها اتجاهه واختار لنفسه لقب ملك النمسا والتي أنشأت في سنة 1804. Golo Mann, Deutsche Geschichte des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts, Frankfurt am Main, 2002, p. 70.

- ^

فيخته, يوهان گوتليب (1808). "خطاب إلى الأمة الألمانية". www.historyman.co.uk. Retrieved 08 أغسطس 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ James Sheehan, German History, 1780–1866, Oxford, 1989, pp. 434.

- ^ Jakob Walter, and Marc Raeff. The diary of a Napoleonic foot soldier. Princeton, N.J., 1996.

- ^ Sheehan, pp. 384–387.

- ^ حقق الجيش البروسي سمعة طيبة في حرب السنوات السبع إلا أن هزيمته في معركتي جينا وأويرستايد حطمت كبرياء الجنود البروسيين. وخلال منفاهم، فكر عدة ضباط منهم كارل فون كلاوزفيتس في إعادة تنظيم الجيش وابتكروا طرقا تدريبية جديدة. انظر Sheehan صفحة 323.

- ^ Sheehan, pp. 322–23.

- ^ David Blackbourn, and Geoff Eley. The peculiarities of German history: bourgeois society and politics in nineteenth-century Germany. Oxford & New York, 1984, part 1; Thomas Nipperdey, German History From Napoleon to Bismarck, 1800–1871, New York, Oxford, 1983. Chapter 1.

- ^ Sheehan, pp. 398–410; Hamish Scott, The Birth of a Great Power System, 1740–1815, US, 2006, pp. 329–361.

- ^ Sheehan, pp. 398–410.

- ^ Jean Berenger. A History of the Habsburg Empire 1700-1918. C. Simpson, Trans. New York: Longman, 1997, ISBN 0-582-09007-5. pp. 96-97.

- ^ Lloyd Lee, Politics of Harmony: Civil Service, Liberalism, and Social Reform in Baden, 1800–1850, Cranbury, NJ, 1980.

- ^ Adam Zamoyski, Rites of Peace: The Fall of Napoleon and the Congress of Vienna, New York, 2007, pp. 98–115, 239–40.

- ^ L.B. Namier, (1952) Avenues of History. London, ONT, 1952, p. 34.

- ^ Nipperdey, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Sheehan, pp. 407–408, 444.

- ^ Sheehan, pp. 442–445.

- ^ Sheehan, pp. 465–67; Blackbourn, Long Century, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Sheehan, pp. 460–470. معهد التاريخ الألماني

- ^ Sheehan, p. 465.

- ^ Sheehan, p. 466.

- ^ Sheehan, pp. 467–468.

- ^ Sheehan, p. 502.

- ^ Sheehan, p. 469.

- ^ Sheehan, p. 458.

- ^ Sheehan, pp. 466–467.

- ^ تتبعا جذور اللغة الألمانية ورسما خطوط تطورها معا. الأخوان غريم أونلاين. إصدارات مشتركة.

- ^ (بالألمانية) Hans Lulfing, Baedecker, Karl, Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 1, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1953, p. 516 f.

- ^ (بالألمانية) Peter Rühmkorf, Heinz Ludwig Arnold, Das Lied der Deutschen Göttingen: Wallstein, 2001, ISBN 3892444633, pp. 11–14.

- ^ Raymond Dominick III, The Environmental Movement in Germany, Bloomington, University of Indiana, 1992, pp. 3–41.

- ^ Jonathan Sperber, Rhineland radicals: the democratic movement and the revolution of 1848–1849. Princeton, N.J., 1993.

- ^ أ ب Sheehan, pp. 610–613.

- ^ Sheehan, p. 610.

- ^ Sheehan, p. 612.

- ^ Sheehan, p. 613.

- ^ David Blackbourn, Marpingen: apparitions of the Virgin Mary in nineteenth-century Germany. New York, 1994.

- ^ Sperber, Rhineland radicals. p. 3.

- ^ Blackbourn, Long Century, p. 127.

- ^ Sheehan, pp. 610–615.

- ^ Blackbourn, Long Century, pp. 138–164.

- ^ (بالألمانية) Badische Heimat/Landeskunde online 2006 Veit's Pauls Church Germania. حقق في 22 نوفمبر 2010.

- ^ Jonathan Sperber, Revolutionary Europe, 1780–1850, New York, 2000.

- ^ Blackbourn, Long Century, pp. 176–179.

- ^ Holt & Chilton 1917, p. 27.

- ^ Holt & Chilton 1917, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Blackbourn 1998, pp. 175–179.

- ^ Hollyday, Frederic B. M. (1970). Bismarck. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 16–18. ISBN 978-0-1307-7362-3. OL 4576160M.

- ^ Blackbourn & Eley 1984, Part I.

- ^ Mann 1971, Chapter 6.

- ^ Hull, Isabel V. (2005). Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany (New ed.). Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 90–108, 324–333. ISBN 978-0-8014-7293-0. OL 7848816M.

- ^ Howard 1968, p. 40.

- ^ Mann 1971, pp. 390–395.

- ^ Taylor 1988, Chapter 1 and Conclusion.

- ^ Howard 1968, pp. 40–57.

- ^ Sheehan 1989, pp. 900–904; Wawro 1996, pp. 4–32; Holt & Chilton 1917, p. 75

- ^ Holt & Chilton 1917, p. 75.

- ^ Sheehan, pp. 900–906.

- ^ Sheehan 1989, p. 96; Wawro 1996, pp. 82–84.

- ^ Sheehan 1989, pp. 905–906.

- ^ Sheehan 1989, p. 909.

- ^ Wawro 1996, pp. 50–60, 75–79.

- ^ Wawro 1996, pp. 57–75.

- ^ Taylor 1988, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Sheehan 1989, pp. 908–909.

- ^ The Situation of Germany. (PDF) – The New York Times, July 1, 1866.

- ^ Sheehan 1989, p. 910.

- ^ Blackbourn 1998, Chapter V: From Reaction to Unification.

- ^ Schjerve, Rosita Rindler (2003). Diglossia and Power: Language Policies and Practice in the Nineteenth Century Habsburg Empire. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 199–200. ISBN 978-3-1101-7654-4. OL 9017475M.

- ^ Sheehan 1989, pp. 909–910; Wawro 1996, Chapter 11.

- ^ Sheehan 1989, pp. 905–910.

- ^ Bridge, Roy; Bullen, Roger (2004). The Great Powers and the European States System 1814–1914 (2nd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-0-5827-8458-1. OL 7882098M.[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ Howard 1968, pp. 4–60.

- ^ Howard 1968, pp. 50–57.

- ^ Howard 1968, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Howard 1968, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Howard 1968, pp. 55–59.

- ^ Howard 1968, pp. 64–68.

- ^ Howard 1968, pp. 218–222.

- ^ Howard 1968, pp. 222–230.

- ^ Wawro 2003, p. 235.

- ^ Taylor 1988, p. 126.

- ^ Howard 1968, pp. 357–370.

- ^ Die Reichsgründung 1871 (The Foundation of the Empire, 1871), Lebendiges virtuelles Museum Online, accessed 2008-12-22. German text translated: [...] on the wishes of Wilhelm I, on the 170th anniversary of the elevation of the House of Brandenburg to princely status on January 18, 1701, the assembled German princes and high military officials proclaimed Wilhelm I as German Emperor in the Hall of Mirrors at the Versailles Palace.

- ^ Taylor 1988, p. 133.

- ^ Crankshaw, Edward (1981). Bismarck. New York: The Viking Press. p. 299. ISBN 0-3333-4038-8. OL 28022489M.

- ^ Howard 1968, Chapter XI: the Peace.

- ^ Blackbourn 1998, pp. 255–257.

- ^ Wawro 2003, p. 302.

- ^ أ ب Confino 1997.

- ^ Evans 2005, p. 1.

- ^ Richard J. Evans, Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years, 1830–1910. New York, 2005, p. 1.

- ^ Blackbourn 1998, p. 267.

- ^ Blackbourn 1998, pp. 225–301.

- ^ Blackbourn & Eley 1984; Blickle 2004; Scribner & Ogilvie 1996.[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ See, e.g.: Eley, Geoff (1980). Reshaping the German Right: Radical Nationalism and Political Change After Bismarck. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-3000-2386-3. OCLC 5353122. OL 4416729M.; Evans 2005; Evans, Richard J. (1978). Society and politics in Wilhelmine Germany. London and New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 0-06-492036-4. OCLC 3934998. OL 21299242M.; Nipperdey 1996; Sperber 1984.[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ Blackbourn 1998, pp. 240–290.

- ^ See, e.g.: Llobera & Goldsmiths' College 1996; (in ألمانية) Alexandre Escudier, Brigitte Sauzay, and Rudolf von Thadden. Gedenken im Zwiespalt: Konfliktlinien europäischen Erinnerns, Genshagener Gespräche; vol. 4. Göttingen: 2001

- ^ Blackbourn 1998, pp. 243–282.

- ^ Gross, Michael B., The war against Catholicism: liberalism and the anti-Catholic imagination in nineteenth-century Germany, p. 1, University of Michigan Press, 2004

- ^ Blackbourn 1998, pp. 283, 285–300.

- ^ Sperber 1984.

- ^ Kaplan 1991.

- ^ Kaplan 1991, in particular, pp. 4–7 and Conclusion.

- ^ Blackbourn & Eley 1984, p. 241.

- ^ Friedrich, Karin (2000). The Other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and Liberty, 1569–1772. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-5210-2775-5. OL 7714437M.

- ^ See, e.g.: Koshar, Rudy (1998). Germany's Transient Pasts: Preservation and the National Memory in the Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4701-5. OCLC 45729918. OL 689805M.; Kohn, Hans (1954). German History; Some New German Views. Boston: Beacon. OCLC 987529. OL 24208090M.; Nipperdey 1996.

- ^ Llobera & Goldsmiths' College 1996.

المراجع

- Berghahn, Volker. Modern Germany: Society, Economy and Politics in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0521347488

- Beringer, Jean. A History of the Habsburg Empire 1700–1918. C. Simpson, Trans. New York: Longman, 1997, ISBN 0-582-09007-5.

- Blackbourn, David. Marpingen: apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Bismarckian Germany. New York: Knopf, 1994. ISBN 0679418431

- __. The long nineteenth century: a history of Germany, 1780–1918. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0195076729

- __ and Geoff Eley. The peculiarities of German history: bourgeois society and politics in nineteenth-century Germany. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0198730576

- Blickle, Peter. Heimat: a critical theory of the German idea of homeland. Studies in German literature, linguistics and culture. Columbia, South Carolina: Camden House Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0582784581

- Bridge, Roy and Roger Bullen, The Great Powers and the European States System 1814–1914, 2nd ed. Longman, 2004. ISBN 978-0582784581

- Confino, Alon. The Nation as a Local Metaphor: Württemberg, Imperial Germany, and National Memory, 1871–1918. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-8078-4665-0

- Crankshaw, Edward. Bismarck. New York, The Viking Press, 1981. ISBN 0333340388

- (بالألمانية) Dahrendorf, Ralf. Gesellschaft und Demokratie in Deutschland. Munich:, Piper, 1965. OCLC 2996408

- Dominick, Raymond III, The Environmental Movement in Germany, Bloomington, Indiana University, 1992. ISBN 0-253-31819-X

- (بالألمانية) Escudier, Alexandre, Brigitte Sauzay, and Rudolf von Thadden. "Gedenken im Zwiespalt: Konfliktlinien europäischen Erinnerns", in Genshagener Gespräche Vol. 4. Göttingen, Wallstein, 2001. ISBN 978-3525358702

- Evans, Richard J. Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years, 1830–1910. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0143036364

- __. Rethinking German history: nineteenth-century Germany and the origins of the Third Reich. London, Routledge, 1987. ISBN 978-0003020908

- Flores, Richard R. Remembering the Alamo: memory, modernity, and the master symbol. Austin: University of Texas, 2002. ISBN 978-0292725409

- Friedrich, Karin, The other Prussia: royal Prussia, Poland and liberty, 1569–1772, New York, 2000. ISBN 978-0521027755

- Grew, Raymond. Crises of Political Development in Europe and the United States. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1978. ISBN 0691075980

- Hollyday, F. B. M. Bismarck. New Jersey, Prentice Hall, 1970. ISBN 978-0130773623

- Holt, Alexander W. The History of Europe from 1862–1914: From the Accession of Bismarck to the Outbreak of the Great War. New York: MacMillan, 1917. OCLC 300969997

- Howard, Michael Eliot. The Franco-Prussian War: the German invasion of France, 1870–1871. New York, MacMillan, 1961. ISBN 978-0415027878

- Hull, Isabel. Absolute Destruction: Military culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany. Ithaca, New York, Syracuse University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0801472930

- Kann, Robert A. History of the Habsburg Empire: 1526–1918. Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1974 ISBN 978-0520042063

- Kaplan, Marion. The making of the Jewish middle class: women, family, and identity in Imperial Germany. New York, Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0195093964

- Kocka, Jürgen and Allan Mitchell. Bourgeois society in nineteenth century Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0854964147

- __. "German History before Hitler: The Debate about the German Sonderweg." Journal of Contemporary History Vol. 23, No. 1 (January 1988), p. 3–16.

- __. "Comparison and Beyond.'" History and Theory Vol. 42, No. 1 (February 2003), p. 39–44.

- __. "Asymmetrical Historical Comparison: The Case of the German Sonderweg". History and Theory Vol. 38, No. 1 (February 1999), p. 40–50.

- Kohn, Hans. German history; some new German views. Boston: Beacon, 1954. OCLC 987529

- Koshar, Rudy, Germany's Transient Pasts: Preservation and the National Memory in the Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill, 1998. ISBN 978-0807847015

- Krieger, Leonard. The German Idea of Freedom, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1957. ISBN 978-1597405195

- Lee, Lloyd. The politics of Harmony: Civil Service, Liberalism, and Social Reform in Baden, 1800–1850. Cranbury, New Jersey, Associated University Presses, 1980. ISBN 978-0874131437

- Llobera, Josep R. and Goldsmiths' College. "The role of historical memory in (ethno)nation-building." Goldsmiths Sociology Papers. London, Goldsmiths College, 1996. ISBN 978-0902986060

- (بالألمانية) Mann, Golo. Deutsche Geschichte des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 2002. ISBN 978-3103479058

- Namier, L.B.. Avenues of History. New York, Macmillan, 1952. OCLC 422057575

- Nipperdey, Thomas. Germany from Napoleon to Bismarck, 1800–1866. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0691026367

- Schjerve, Rosita Rindler, Diglossia and Power: Language Policies and Practice in the nineteenth century Habsburg Empire. Berlin, De Gruyter, 2003. ISBN 978-3110176544

- Schulze, Hagen. The course of German nationalism: from Frederick the Great to Bismarck, 1763–1867. Cambridge & New York, Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0521377591

- Scott, H. M. The Birth of a Great Power System. London & New York, Longman, 2006. ISBN 978-0582217171

- Scribner, Robert W. and Sheilagh C. Ogilvie. Germany: a new social and economic history. London: Arnold Publication, 1996. ISBN 978-0340513323

- Sheehan, James J. German history 1770–1866. Oxford History of Modern Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0198204329

- Sked, Alan. Decline and Fall of the Habsburg Empire 1815–1918. London, Longman, 2001. ISBN 978-0582356665

- Smith, Denis Mack (editor). Garibaldi (Great Lives Observed), Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1969. ASIN: B001Q8OJZ2

- Sorkin, David, The transformation of German Jewry, 1780–1840, Studies in Jewish history. New York, Wayne State University Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0814328286

- Sperber, Jonathan. The European Revolutions, 1848–1851. New Approaches to European History. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0521547796

- __. Popular Catholicism in nineteenth century Germany. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0691054322

- __. Rhineland radicals: the democratic movement and the revolution of 1848–1849. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0691008660

- Stargardt, Nicholas. The German idea of militarism: radical and socialist critics, 1866–1914. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0521466929

- Taylor, A. J. P., The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1914–1918, Oxford, Clarendon, 1954. ISBN 978-0198812708

- __. Bismarck: The Man and the Statesman. Oxford: Clarendon, 1988. ISBN 978-0394703879

- Vann, James Allen. The Swabian Kreis: Institutional Growth in the Holy Roman Empire 1648–1715. Vol. LII, Studies Presented to the International Commission for the History of Representative and Parliamentary Institutions. Bruxelles, Editions de la librairie encyclopedique, 1975. ISBN 978-0801415531

- Victoria and Albert Museum, Dept. of Prints and Drawings, and Susan Lambert. The Franco-Prussian War and the Commune in caricature, 1870–71. London, 1971. ISBN 0901486302

- Walter, Jakob and Marc Raeff (trans/ed). The diary of a Napoleonic foot soldier. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0140165593

- Walker, Mack. German home towns: community, state, and general estate, 1648–1871. Ithaca, Syracuse University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0801485084

- Wawro, Geoffrey. The Austro-Prussian War. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-62951-9

- ___. Warfare and Society in Europe, 1792–1914. 2000. ISBN 978-0415214452

- (بالألمانية) Wehler, Hans Ulrich. Das Deutsche Kaiserreich, 1871–1918. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1973. ISBN 978-0907582328

- (بالألمانية) "wr/as", Die Reichsgründung 1871 (The Foundation of the Empire, 1871), Lebendiges virtuelles Museum Online, Accessed 2008-12-22. The article is signed "wr/as".

- Zamoyski, Adam. Rites of Peace: The Fall of Napoleon and the Congress of Vienna. New York, HarperCollins, 2007. ISBN 978-0060775193

قراءات إضافية

- Bazillion, Richard J. Modernizing Germany: Karl Biedermann's career in the kingdom of Saxony, 1835–1901. American university studies. Series IX, History, vol. 84. New York, Peter Lang, 1990. ISBN 082041185X

- Bucholz, Arden. Moltke, Schlieffen, and Prussian war planning. New York, Berg Pub Ltd, 1991. ISBN 0854966536

- ___. Moltke and the German Wars 1864–1871. New York, Palgrave MacMillan, 2001. ISBN 0333687582

- Clark, Christopher. Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947. Cambridge, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006, 2009. ISBN 978-0674031968

- Clemente, Steven E. For King and Kaiser!: the making of the Prussian Army officer, 1860–1914. Contributions in military studies, no. 123. New York: Greenwood, 1992. ISBN 0313280045