كانبرا

}}}}

| Canberra Kanbarra (Ngunawal) Australian Capital Territory | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

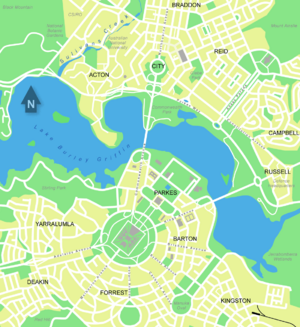

City map plan of Canberra | |||||||||

| Coordinates | 35°17′35″S 149°07′37″E / 35.29306°S 149.12694°E | ||||||||

| Population | 473,855 (June 2024)[1] (8th) | ||||||||

| • Density | 503٫932/km2 (1،305.18/sq mi) | ||||||||

| Established | 12 March 1913 | ||||||||

| Elevation | 578 m (1،896 ft)[2] | ||||||||

| Area | 814٫2 km2 (314٫4 sq mi)[3] | ||||||||

| Time zone | AEST (UTC+10:00) | ||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | AEDT (UTC+11:00) | ||||||||

| Location | |||||||||

| Territory electorate(s) | |||||||||

| Federal division(s) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

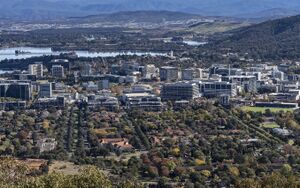

كانبرا ( Canberra ؛ /ˈkænbrə/ (![]() استمع) KAN-brə؛ Ngunawal: Kanbarra)[10])، هي العاصمة الاتحادية القومية لأستراليا. تأسست عقب federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city, and the eighth-largest Australian city by population. The city is located at the northern end of the Australian Capital Territory[11] at the northern tip of the Australian Alps, the country's highest mountain range. اعتبارا من June 2024[تحديث] Canberra's estimated population was 473,855.[1]

استمع) KAN-brə؛ Ngunawal: Kanbarra)[10])، هي العاصمة الاتحادية القومية لأستراليا. تأسست عقب federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city, and the eighth-largest Australian city by population. The city is located at the northern end of the Australian Capital Territory[11] at the northern tip of the Australian Alps, the country's highest mountain range. اعتبارا من June 2024[تحديث] Canberra's estimated population was 473,855.[1]

ويبلغ عدد سكانها ما يزيد عن 332,000 نسمة. وتقع ضمن ولاية نيو ساوث ويلز التي عاصمتها مدينة سيدني.

The area chosen for the capital had been inhabited by Aboriginal Australians for up to 21,000 years,[12] by groups including the Ngunnawal and Ngambri.[13] European settlement commenced in the first half of the 19th century, as evidenced by surviving landmarks such as St John's Anglican Church and Blundells Cottage. On 1 January 1901, federation of the colonies of Australia was achieved. Following a long dispute over whether Sydney or Melbourne should be the national capital,[14] a compromise was reached: the new capital would be built in New South Wales, so long as it was at least 100 mi (160 km) from Sydney. The capital city was founded and formally named as Canberra in 1913. A plan by the American architects Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin was selected after an international design contest, and construction commenced in 1913.[15][16] Unusual among Australian cities, it is an entirely planned city. The Griffins' plan featured geometric motifs and was centred on axes aligned with significant topographical landmarks such as Black Mountain, Mount Ainslie, Capital Hill and City Hill. Canberra's mountainous location makes it the only mainland Australian city where snow-capped mountains can be seen for much of the winter, although snow in the city itself is uncommon.

As the seat of the Government of Australia, Canberra is home to many important institutions of the federal government, national monuments and museums. These include Parliament House, Government House, the High Court building and the headquarters of numerous government agencies. It is the location of many social and cultural institutions of national significance such as the Australian War Memorial, the Australian National University, the Royal Australian Mint, the Australian Institute of Sport, the National Gallery, the National Museum and the National Library. The city is home to many important institutions of the Australian Defence Force including the Royal Military College Duntroon and the Australian Defence Force Academy. It hosts all foreign embassies in Australia as well as regional headquarters of many international organisations, not-for-profit groups, lobbying groups and professional associations.

Canberra has been ranked among the world's best cities to live in and visit.[17][18][19][20][21] Although the Commonwealth Government remains the largest single employer in Canberra, it is no longer the majority employer. Other major industries have developed in the city, including in health care, professional services, education and training, retail, accommodation and food, and construction.[22] Compared to the national averages, the unemployment rate is lower and the average income higher; tertiary education levels are higher, while the population is younger. At the 2021 Census, 28.7% of Canberra's inhabitants were reported as having been born overseas.[23]

Canberra's design is influenced by the garden city movement and incorporates significant areas of natural vegetation. Its design can be viewed from its highest point at the Telstra Tower and the summit of Mount Ainslie. Other notable features include the National Arboretum, born out of the 2003 Canberra bushfires, and Lake Burley Griffin, named for Walter Burley Griffin. Highlights in the annual calendar of cultural events include Floriade, the largest flower festival in the Southern Hemisphere,[24][25] the Enlighten Festival, Skyfire, the National Multicultural Festival and Summernats. Canberra's main sporting venues are Canberra Stadium and Manuka Oval. The city is served with domestic and international flights at Canberra Airport, while interstate train and coach services depart from Canberra railway station and the Jolimont Centre respectively. City Interchange and Alinga Street station form the main hub of Canberra's bus and light rail transport network.

الاسم

The word "Canberra" is derived from the Ngunnawal language of a local Ngunnawal or Ngambri clan who resided in the area and were referred to by the early British colonists as either the Canberry, Kanberri or Nganbra tribe.[26][27] Joshua John Moore, the first European land-owner in the region, named his grant "Canberry" in 1823 after these people. "Canberry Creek" and "Canberry" first appeared on regional maps from 1830, while the derivative name "Canberra" started to appear from around 1857.[28][29][30] Other early recorded variants of the spelling include "Canbury" (potentially influenced by the settlement of the same name in England), "Canburry" and "Kembery".[31]

Numerous local commentators, including the Ngunnawal elder Don Bell, have speculated upon possible meanings of "Canberra" over the years. These include "meeting place", "woman's breasts" and "the hollow between a woman's breasts".[32][33]

Alternative proposals for the name of the city during its planning included Austral, Australville, Aurora, Captain Cook, Caucus City, Cookaburra, Dampier, Eden, Eucalypta, Flinders, Gonebroke, Home, Hopetoun, Kangaremu, Myola, Meladneyperbane, New Era, Olympus, Paradise, Shakespeare, Sydmelperadbrisho, Swindleville, The National City, Union City, Unison, Wattleton, Wheatwoolgold, Yass-Canberra.[34][35][36]

التاريخ

كان سكان أستراليا الأصليون يعيشون في منطقة كانبرا منذ أربعة آلاف سنة على الأقل. وقد اكتشف كهف يحتوي على رسومات حائطية في منطقة جدجنبي جنوبي مدينة كانبرا.

وزار المستكشفون الأوروبيون لأول مرة السهول الجيرية في شهر ديسمبر 1820. وقام جوسف وايلد مع تشارلز ثروزبي سميث، وهو جراح سابق في البحرية البريطانية، ومعهم جيمس نوجان بنصب خيامهم في نفس المكان الذي تقوم عليه المدينة الآن. وفي سنة 1821، زار ثروزبي ووايلد المنطقة مرة أخرى واكتشفا نهر مرمبيجي.[37]

وفي سنة 1824م، أقام جاشوا مور مزرعة لتربية المواشي بالقرب من الموقع الحالي لمستشفى كانبرا، التي أطلق عليها اسم كانبري اعتقادًا منه بأن ذلك هو الاسم الأصلي للمكان. ويعتقد أن كلمة كانبري تعني في لغة السكان الأصليين مكان اللِّقاء. وبعد تسعين عامًا، تحول الاسم مع الاستخدام إلى كانبرا، واختير اسمًا للعاصمة الوطنية.

وفي سنة 1900م، وافق البرلمان البريطاني على قانون دستور الكومنولث الأسترالي الذي نص على أن يكون للحكومة عضوية في المجلس التشريعي الفدرالي.

بعد سنوات من الخلاف والصراع، اختار س. آر. سكريفنز، وهو مسّاح مناطق ولاية نيو ساوث ويلز موقع كانبرا في عام 1908م. وفي 1 يناير 1911م، تمّ ميلاد إقليم أستراليا الأساسي. وفي 1915م، قدمت ولاية نيو ساوث ويلز منطقة تبلغ مساحتها 73 كم² على الساحل عند خليج جافاز لاستخدامها ميناءً للعاصمة الفيدرالية.

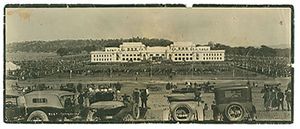

أعلنت الحكومة الفدرالية في 1911 عن مسابقة عالمية لتصميم العاصمة الوطنية، ومن بين العروض المقدمة والتي بلغ عددها 137 عرضًا، تم منح المهندس المعماري الأمريكي والتر برلي گريفن Walter Burley Griffin وهو مهندس مناظر معماري من مدينة شيكاغو الجائزة الأولى وقدرها 1,750 جنيهًا أستراليًا، وقامت لجنة وزارية عينتها الحكومة بتغيير خطة جريفين واقترحت أخرى خاصة بها، تبنتها الحكومة في 10 يناير 1913. وشرع وزير الشؤون الداخلية كينج أومالي في الشهر التالي في أعمال البناء. وفي يوم 12 مارس 1913، أطلقت السيدة زوجة الحاكم العام حينئذ، دينمان ، اسم كانبرا رسميًا على العاصمة الوطنية.[37]

وفي نهاية عام 1913، وصل والتر بيرلي جريفين إلى أستراليا وقبل وظيفة مدير العاصمة الفيدرالية للتصميم والتعمير. وأعيد قبول خطته وأُسْقِطَت الخطة الوزارية. وفي عام 1920م، قطع والتر بيرلي جريفين صلته بتخطيط كانبرا إلا أنه كان قد أكمل بالفعل قواعد خطته وأقامت الحكومة عندئذ اللجنة الاستشارية للعاصمة الوطنية تحت رئاسة المعماري السير جون سولمان. وفي عام 1925، عينت الحكومة جهازًا آخر للتخطيط، وهي لجنة العاصمة الفدرالية والتي رأسها المهندس السير جون بتارز. ونمت مدينة كانبرا بسرعة.

وبدأت الحكومة في نقل الموظفين الحكوميين من ملبورن. وفي عام 1930، تم حل لجنة العاصمة الفيدرالية، ومع الكساد توقفت تقريبًا أعمال البناء.

في عام 1941، تم الانتهاء من إقامة النصب التذكاري الحربي الأسترالي. وبدأت الحكومة عام 1948 في نقل المزيد من الموظفين الحكوميين من ملبورن وتم إنشاء لجنة تنمية العاصمة الوطنية عام 1958، التي قررت بناء البحيرات على نهر مولونجلو، التي كانت من معالم خطة والتر بيرلي جريفين. وقد تم بناء بحيرة بيرلي جريفين في أوائل الستينيات وتبعتها بحيرة جينْيندار في السبعينيات من القرن العشرين.

وفي عام 1980، قام ستة من القضاة باختيار تصميم ريتشارد ثورب لمبنى البرلمان الجديد الذي يقع على تل مرتفع خلف مبنى البرلمان القديم. وقامت الملكة إليزابيث الثانية بافتتاح مبنى البرلمان الجديد يوم 9 مايو عام 1988، في أثناء احتفالات الذكرى المائتين لأستراليا.

الجغرافيا

تقع كانبرا شمال أستراليا، 300 كم جنوب غرب سيدني و 650 كم شمال شرق ملبورن. وقد تمّ اختيارها عاصمة لأستراليا في 1908 وذلك نظرا لموقعها بين أكبر مدينتين، سيدني وملبورن.

تقع كانبرا على ارتفاع 600م فوق مستوى سطح البحر، فوق المنحدرات الدنيا من المرتفعات الشرقية الأسترالية، وتبعد عن شاطئ المحيط الهادئ غرباً نحو 145كم. وعن سدني نحو 306 كم، وتبعد عن ملبورن نحو 600 كم. يمرّ فيها خط العرض 20 َ 30 ْ جنوب خط الاستواء، وخط طول 143 ْ شرق گرينتش. وتشغل المدينة مساحة نحو 600كم²، في حين يغطي إقليم العاصمة الاسترالية نحو 2359كم²،ممتداً على المدن المجاورة الملاصقة لها.

المناخ

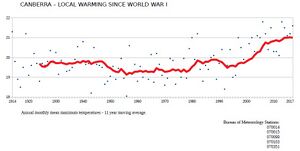

يسود كانبرا مناخ حار صيفاً معتدل مائل للبرودة شتاء، إذ إن متوسط حرارة أبرد شهور السنة تموز/يوليو يبلغ نحو 5.4 ْم، ويبلغ متوسط حرارة أحر الشهور فبراير نحو 20°م. والهطل في المدينة دائم طوال السنة، مع تركيز معظمه في نصف السنة الصيفي نوفمبر - أبريل الذي يكون على شكل أمطار تسببها الرياح البحرية الرطبة القادمة من الضغط المرتفع فوق المحيط الهادي، في حين تهطل أمطار الشتاء بفعل المنخفضات الجوية المدفوعة بالرياح الغربية، ولا تزيد نسبتها على 35%، لوقوع كانبرا في ظل الجبال. يهطل الثلج شتاء مرات عدة، ويبلغ معدل الهطل السنوي نحو 640مم، وتغطي الثلوج الجبال غربي كانبرا شتاء مما يعطي منظراً غربياً جميلاً، يضاف إلى منظر الغابات الجبلية، بعد تحرر الأرض من ثلوجها.

تتمتع كانبرا بفصول السنة الأربعة وذلك لقربها من الشاطئ ، مثلها مثل معظم المدن الأسترالية الساحلية. والطقس بصفة عامة طقس معتدل بارد في الشتاء ، حار جاف صيفا. ونادرا ما يسقط بعض الثلوج في الشتاء. [38]

Under the Köppen-Geiger classification, Canberra has an oceanic climate (Cfb).[39] In January, the warmest month, the average high is approximately 29 °C (84 °F); in July, the coldest month, the average high drops to approximately 12 °C (54 °F).

Frost is common in the winter months. Snow is rare in the CBD (central business district) due to being on the leeward (eastern) side of the dividing range, but the surrounding areas get annual snowfall through winter and often the snow-capped Brindabella Range can be seen from the CBD. The last significant snowfall in the city centre was in 1968.[40] Canberra is often affected by foehn winds, especially in winter and spring, evident by its anomalously warm maxima relative to altitude.

The highest recorded maximum temperature was 44.0 °C (111.2 °F) on 4 January 2020.[41] Winter 2011 was Canberra's warmest winter on record, approximately 2 °C (4 °F) above the average temperature.[42]

The lowest recorded minimum temperature was −10.0 °C (14.0 °F) on the morning of 11 July 1971.[40] Light snow falls only once in every few years, and is usually not widespread and quickly dissipates.[40]

Canberra is protected from the west by the Brindabellas which create a strong rain shadow in Canberra's valleys.[40] Canberra gets 100.4 clear days annually.[43] Annual rainfall is the third lowest of the capital cities (after Adelaide and Hobart)[44] and is spread fairly evenly over the seasons, with late spring bringing the highest rainfall.[45] Thunderstorms occur mostly between October and April,[40] owing to the effect of summer and the mountains. The area is generally sheltered from a westerly wind, though strong northwesterlies can develop. A cool, vigorous afternoon easterly change, colloquially referred to as a 'sea-breeze' or the 'Braidwood Butcher',[46][47] is common during the summer months[48] and often exceeds 40 km/h in the city. Canberra is also less humid than the nearby coastal areas.[40]

Canberra was severely affected by smoke haze during the 2019/2020 bushfires. On 1 January 2020, Canberra had the worst air quality of any major city in the world, with an AQI of 7700 (USAQI 949).[49]

| بيانات المناخ لـ مقارنة مطار كانبرا (1991–2010 averages, extremes 1939–2023); 578 m AMSL; 35.30° S, 149.20° E | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| القصوى القياسية °س (°ف) | 44.0 (111.2) |

42.7 (108.9) |

37.5 (99.5) |

32.6 (90.7) |

24.5 (76.1) |

20.1 (68.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

24.0 (75.2) |

30.2 (86.4) |

32.7 (90.9) |

39.9 (103.8) |

41.6 (106.9) |

44.0 (111.2) |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °س (°ف) | 28.8 (83.8) |

27.8 (82.0) |

24.9 (76.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

16.6 (61.9) |

12.9 (55.2) |

12.1 (53.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.4 (74.1) |

26.5 (79.7) |

20.4 (68.7) |

| المتوسط اليومي °س (°ف) | 21.4 (70.5) |

20.8 (69.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.3 (45.1) |

6.2 (43.2) |

7.5 (45.5) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °س (°ف) | 14.0 (57.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.9 (51.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.4 (38.1) |

1.6 (34.9) |

0.3 (32.5) |

1.2 (34.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.1 (53.8) |

7.0 (44.6) |

| متوسط الدنيا °س (°ف) | 7.7 (45.9) |

7.7 (45.9) |

4.1 (39.4) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

2.2 (36.0) |

5.3 (41.5) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

| الصغرى القياسية °س (°ف) | 1.6 (34.9) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

0.3 (32.5) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار mm (inches) | 61.3 (2.41) |

55.2 (2.17) |

37.6 (1.48) |

27.3 (1.07) |

31.5 (1.24) |

50.0 (1.97) |

44.3 (1.74) |

43.1 (1.70) |

55.8 (2.20) |

50.9 (2.00) |

68.4 (2.69) |

54.1 (2.13) |

579.5 (22.81) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 6.8 | 6.7 | 5.7 | 5.4 | 6.3 | 9.7 | 10.0 | 8.5 | 9.8 | 9.1 | 10.2 | 7.2 | 95.4 |

| متوسط الرطوبة النسبية بعد الظهر (%) | 37 | 40 | 42 | 46 | 54 | 60 | 58 | 52 | 49 | 47 | 41 | 37 | 47 |

| متوسط نقطة الندى °س (°ف) | 8.6 (47.5) |

9.8 (49.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

6.4 (43.5) |

5.0 (41.0) |

3.5 (38.3) |

2.3 (36.1) |

2.1 (35.8) |

3.7 (38.7) |

5.4 (41.7) |

6.3 (43.3) |

6.9 (44.4) |

5.7 (42.3) |

| Mean monthly ساعات سطوع الشمس | 294.5 | 254.3 | 251.1 | 219.0 | 186.0 | 156.0 | 179.8 | 217.0 | 231.0 | 266.6 | 267.0 | 291.4 | 2٬813٫7 |

| Source 1: Climate averages for Canberra Airport Comparison (1939–2010); averages given are for 1991–2010[43][50][51] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Records from Canberra Airport for more recent extremes[52] | |||||||||||||

البنية الحضرية

Canberra is a planned city and the inner-city area was originally designed by Walter Burley Griffin, a major 20th-century American architect.[53] Within the central area of the city near Lake Burley Griffin, major roads follow a wheel-and-spoke pattern rather than a grid.[54] Griffin's proposal had an abundance of geometric patterns, including concentric hexagonal and octagonal streets emanating from several radii.[54] However, the outer areas of the city, built later, are not laid out geometrically.[55]

Lake Burley Griffin was deliberately designed so that the orientation of the components was related to various topographical landmarks in Canberra.[56][57] The lakes stretch from east to west and divided the city in two; a land axis perpendicular to the central basin stretches from Capital Hill—the eventual location of the new Parliament House on a mound on the southern side—north northeast across the central basin to the northern banks along Anzac Parade to the Australian War Memorial.[58] This was designed so that looking from Capital Hill, the War Memorial stood directly at the foot of Mount Ainslie. At the southwestern end of the land axis was Bimberi Peak,[57] the highest mountain in the ACT, approximately 52 km (32 mi) south west of Canberra.[59]

The straight edge of the circular segment that formed the central basin of Lake Burley Griffin was perpendicular to the land axis and designated the water axis, and it extended northwest towards Black Mountain.[57] A line parallel to the water axis, on the northern side of the city, was designated the municipal axis.[60] The municipal axis became the location of Constitution Avenue, which links City Hill in Civic Centre and both Market Centre and the Defence precinct on Russell Hill. Commonwealth Avenue and Kings Avenue were to run from the southern side from Capital Hill to City Hill and Market Centre on the north respectively, and they formed the western and eastern edges of the central basin. The area enclosed by the three avenues was known as the Parliamentary Triangle, and formed the centrepiece of Griffin's work.[57][60]

The Griffins assigned spiritual values to Mount Ainslie, Black Mountain, and Red Hill and originally planned to cover each of these in flowers. That way each hill would be covered with a single, primary colour which represented its spiritual value.[61] This part of their plan never came to fruition, as World War I slowed construction and planning disputes led to Griffin's dismissal by Prime Minister Billy Hughes after the war ended.[62][63][64]

The urban areas of Canberra are organised into a hierarchy of districts, town centres, group centres, local suburbs as well as other industrial areas and villages. There are seven residential districts, each of which is divided into smaller suburbs, and most of which have a town centre which is the focus of commercial and social activities.[65] The districts were settled in the following chronological order:

- Canberra Central, mostly settled in the 1920s and 1930s, with expansion up to the 1960s,[66] 25 suburbs

- Woden Valley, first settled in 1964,[67] 12 suburbs

- Belconnen, first settled in 1966,[67] 27 suburbs (2 not yet developed)

- Weston Creek, settled in 1969, 8 suburbs[68]

- Tuggeranong, settled in 1974,[69] 18 suburbs

- Gungahlin, settled in the early 1990s, 18 suburbs (3 not yet developed)

- Molonglo Valley, development began in 2010, 13 suburbs planned.

The Canberra Central district is substantially based on Walter Burley Griffin's designs.[57][60][70] In 1967 the then National Capital Development Commission adopted the "Y Plan" which laid out future urban development in Canberra around a series of central shopping and commercial area known as the 'town centres' linked by freeways, the layout of which roughly resembled the shape of the letter Y,[71] with Tuggeranong at the base of the Y and Belconnen and Gungahlin located at the ends of the arms of the Y.[71]

Development in Canberra has been closely regulated by government,[72][73] both through planning processes and the use of crown lease terms that have tightly limited the use of parcels of land. Land in the ACT is held on 99-year crown leases from the national government, although most leases are now administered by the Territory government.[74] There have been persistent calls for constraints on development to be liberalised,[73] but also voices in support of planning consistent with the original 'bush capital' and 'urban forest' ideals that underpin Canberra's design.[75]

Many of Canberra's suburbs are named after former Prime Ministers, famous Australians, early settlers, or use Aboriginal words for their title.[76] Street names typically follow a particular theme; for example, the streets of Duffy are named after Australian dams and reservoirs, the streets of Dunlop are named after Australian inventions, inventors and artists and the streets of Page are named after biologists and naturalists.[76] Most diplomatic missions are located in the suburbs of Yarralumla, Deakin, and O'Malley.[77] There are three light industrial areas: the suburbs of Fyshwick, Mitchell, and Hume.[78]

| المعالم، متجهين جنوباً من جبل إينسلي | |||

الاستدامة والبيئة

The average Canberran was responsible for 13.7 tonnes of greenhouse gases in 2005.[80] In 2012, the ACT Government legislated greenhouse gas targets to reduce its emissions by 40 per cent from 1990 levels by 2020, 80 per cent by 2050, with no net emissions by 2060.[81] The government announced in 2013 a target for 90% of electricity consumed in the ACT to be supplied from renewable sources by 2020,[82] and in 2016 set an ambitious target of 100% by 2020.[83][84]

In 1996, Canberra became the first city in the world to set a vision of no waste, proposing an ambitious target of 2010 for completion.[85] The strategy aimed to achieve a waste-free society by 2010, through the combined efforts of industry, government and community.[86] By early 2010, it was apparent that though it had reduced waste going to landfill, the ACT initiative's original 2010 target for absolutely zero landfill waste would be delayed or revised to meet the reality.[87][88]

Plastic bags made of polyethylene polymer with a thickness of less than 35 μm were banned from retail distribution in the ACT from November 2011.[89][90][91] The ban was introduced by the ACT Government in an effort to make Canberra more sustainable.[90]

Of all waste produced in the ACT, 75 per cent is recycled.[92] Average household food waste in the ACT remains above the Australian average, costing an average $641 per household per annum.[93]

Canberra's annual Floriade festival features a large display of flowers every Spring in Commonwealth Park. The organisers of the event have a strong environmental standpoint, promoting and using green energy, "green catering", sustainable paper, the conservation and saving of water.[79] The event is also smoke-free.[79]

الحكومة والسياسة

الحكومة الإقليمية

There is no local council or city government for the city of Canberra. The Australian Capital Territory Legislative Assembly performs the roles of both a city council for the city and a territory government for the rest of the Australian Capital Territory.[94] However, the vast majority of the population of the Territory reside in Canberra and the city is therefore the primary focus of the ACT Government.

The assembly consists of 25 members elected from five districts using proportional representation. The five districts are Brindabella, Ginninderra, Kurrajong, Murrumbidgee and Yerrabi, which each elect five members.[95] The Chief Minister is elected by the Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) and selects colleagues to serve as ministers alongside him or her in the Executive, known informally as the cabinet.[94]

Whereas the ACT has federally been dominated by Labor,[96][97] the Liberals have been able to gain some footing in the ACT Legislative Assembly and were in government during a period of 61⁄2 years from 1995 and 2001. Labor took back control of the Assembly in 2001.[98] At the 2004 election, Chief Minister Jon Stanhope and the Labor Party won 9 of the 17 seats allowing them to form the ACT's first majority government.[98] Since 2008, the ACT has been governed by a coalition of Labor and the Greens.[98][99][100] اعتبارا من 2022[تحديث], the Chief Minister was Andrew Barr from the Australian Labor Party.

The Australian federal government retains some influence over the ACT government. In the administrative sphere, most frequently this is through the actions of the National Capital Authority which is responsible for planning and development in areas of Canberra which are considered to be of national importance or which are central to Griffin's plan for the city,[101] such as the Parliamentary Triangle, Lake Burley Griffin, major approach and processional roads, areas where the Commonwealth retains ownership of the land or undeveloped hills and ridge-lines (which form part of the Canberra Nature Park).[101][102][103] The national government also retains a level of control over the Territory Assembly through the provisions of the Australian Capital Territory (Self-Government) Act 1988.[104] This federal act defines the legislative power of the ACT assembly.[105]

التمثيل الاتحادي

The ACT was given its first federal parliamentary representation in 1949 when it gained a seat in the House of Representatives, the Division of Australian Capital Territory.[106][107] However, until 1966, the ACT member could only vote on matters directly affecting the territory and did not count for purposes of forming government.[107] In 1974, the ACT was allocated two Senate seats and the House of Representatives seat was divided into two.[106] A third was created in 1996, but was abolished in 1998 because of changes to the regional demographic distribution.[96] At the 2019 election, the third seat has been reintroduced as the Division of Bean.

The House of Representatives seats have mostly been held by Labor and usually by comfortable margins.[96][97] The Labor Party has polled at least seven percentage points more than the Liberal Party at every federal election since 1990 and their average lead since then has been 15 percentage points.[98] The ALP and the Liberal Party held one Senate seat each until the 2022 election when Independent candidate David Pocock unseated the Liberal candidate Zed Seselja.[108]

القضاء والشرطة

The Australian Federal Police (AFP) provides all of the constabulary services in the territory in a manner similar to state police forces, under a contractual agreement with the ACT Government.[109] The AFP does so through its community policing arm ACT Policing.[110]

People who have been charged with offences are tried either in the ACT Magistrates Court or, for more severe offences, the ACT Supreme Court.[111] Prior to its closure in 2009, prisoners were held in remand at the Belconnen Remand Centre in the ACT but usually imprisoned in New South Wales.[112] The Alexander Maconochie Centre was officially opened on 11 September 2008 by then Chief Minister Jon Stanhope. The total cost for construction was $130 million.[113] The ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal deal with minor civil law actions and other various legal matters.[114][115]

Canberra has the lowest rate of crime of any capital city in Australia اعتبارا من 2019[تحديث].[116] اعتبارا من 2016[تحديث], the most common crimes in the ACT were property related crimes, unlawful entry with intent and motor vehicle theft. They affected 2,304 and 966 people (580 and 243 per 100,000 persons respectively). Homicide and related offences—murder, attempted murder and manslaughter, but excluding driving causing death and conspiracy to murder—affect 1.0 per 100,000 persons, which is below the national average of 1.9 per 100,000. Rates of sexual assault (64.4 per 100,000 persons) are also below the national average (98.5 per 100,000).[117][118][119] However the 2017 crime statistics showed a rise in some types of personal crime, notably burglaries, thefts and assaults.

الاقتصاد

In February 2020, the unemployment rate in Canberra was 2.9% which was lower than the national unemployment rate of 5.1%.[120] As a result of low unemployment and substantial levels of public sector and commercial employment, Canberra has the highest average level of disposable income of any Australian capital city.[121] The gross average weekly wage in Canberra is $1827 compared with the national average of $1658 (November 2019).[122]

The median house price in Canberra as of February 2020 was $745,000, lower than only Sydney among capital cities of more than 100,000 people, having surpassed Melbourne and Perth since 2005.[122][123][124] The median weekly rent paid by Canberra residents is higher than rents in all other states and territories.[125] As of January 2014 the median unit rent in Canberra was $410 per week and median housing rent was $460, making the city the third most expensive in the country.[126] Factors contributing to this higher weekly rental market include; higher average weekly incomes, restricted land supply,[127] and inflationary clauses in the ACT Residential Tenancies Act.[128]

The city's main industry is public administration and safety, which accounted for 27.1% of Gross Territory Product in 2018-19 and employed 32.49% of Canberra's workforce.[129][22] The headquarters of many Australian Public Service agencies are located in Canberra, and Canberra is also host to several Australian Defence Force establishments, most notably the Australian Defence Force headquarters and إتشإمإيهإس Harman, which is a naval communications centre that is being converted into a tri-service, multi-user depot.[130] Other major sectors by employment include Health Care (10.54%), Professional Services (9.77%), Education and Training (9.64%), Retail (7.27%), Accommodation & Food (6.39%) and Construction (5.80%).

The former RAAF Fairbairn, adjacent to the Canberra Airport was sold to the operators of the airport,[131] but the base continues to be used for RAAF VIP flights.[132][133] A growing number of software vendors have based themselves in Canberra, to capitalise on the concentration of government customers; these include Tower Software and RuleBurst.[134][135] A consortium of private and government investors is making plans for a billion-dollar data hub, with the aim of making Canberra a leading centre of such activity in the Asia-Pacific region.[136] A Canberra Cyber Security Innovation Node was established in 2019 to grow the ACT's cyber security sector and related space, defence and education industries.[137]

السكان

يبلغ عدد سكان مدينة كانبرا نحو 300 ألف نسمة، في حين يصل عدد سكان إقليمها إلى 500 ألف نسمة تقريباً لعام 2004. وتعدّ كانبرا مدينة الشباب، إذ يشكل السكان الذين تقل أعمارهم على 18 سنة نحو 40% من إجمالي سكانها، والذين تزيد أعمارهم على 65 سنة يشكّلون نحو 3% فقط. ويسجل معدل النمو السنوي للسكان في مدينة كانبرا أكبر معدل في أستراليا، بسبب تيار الهجرة الكبيرة من الريف والمدن الأخرى نحوها، ولغلبة من هم في سن الشباب. ويحمل ما يقارب من 15% من السكان الذين أعمارهم فوق 25 سنة، شهادات جامعية. يعمل نحو ثلث القوة العاملة من السكان موظفين في الإدارات العامة والدفاع، والخمس في الخدمات الاجتماعية، ونحو 38% في وظائف غير حكومية. وربع الطلاب يتعلّمون في مدارس خاصة تديرها الكنيسة الكاثوليكية. وفي كانبرا الجامعة الوطنية الأسترالية، والعديد من الكليات والمعاهد المتخصصة.

المعالم

تضم كانبرا القاعة الوطنية الأسترالية للفنون، ومكتبة وطنية تحتوي ما يقارب من مليوني كتاب، والمتحف الحربي الذي يعدّ من أشهر معالمها السياحية، وحديقة للحيوان ودار صك العملة الملكية الأسترالية، ومعرض تخطيط المدينة، ودارَ الحكومة الذي شيد عام 1891م كبيت ريفي آنذاك، وفيها الكلية الحربية الملكية والبرلمان ومجموعة من الحدائق النباتية ومتحف وطني للأعشاب.

انظر أيضا

الهامش

- ^ أ ب "Regional population, 2023-24". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 27 March 2025. Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ "GFS / BOM data for CANBERRA AIRPORT". Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةarea - ^ "Great Circle Distance between CANBERRA and SYDNEY". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between CANBERRA and MELBOURNE". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between CANBERRA and ADELAIDE". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between CANBERRA and BRISBANE". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between CANBERRA and PERTH". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ Augmented Electoral Commission for the Australian Capital Territory (July 2018). "Redistribution of the Australian Capital Territory into electoral divisions" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

The electoral divisions described in this report came into effect from Friday 13 July 2018 ... However, members of the House of Representatives will not represent or contest these electoral divisions until ... a general election.

- ^ Macquarie Dictionary (6 ed.). Sydney: Macquarie Dictionary Publishers. 2013. Entry "Canberra". ISBN 9781876429898.

- ^ "Canberra map". Britannica (in الإنجليزية). 2013. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:1 - ^ "Community Stories: Canberra Region". National Museum of Australia (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:2 - ^ Nowroozi, Isaac (19 February 2021). "Celebrating Marion Mahony Griffin, the woman who helped shape Canberra". ABC News (in الإنجليزية الأسترالية). Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ Lewis, Wendy; Balderstone, Simon; Bowan, John (2006). Events That Shaped Australia. New Holland. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-74110-492-9.

- ^ "Canberra ranked 'best place to live' by OECD". BBC News (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). 8 October 2014. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Riordan, Primrose (7 October 2014). "Canberra named the best place in the world...again". The Canberra Times (in الإنجليزية الأسترالية). Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Why Canberra is Australia's most liveable city". Switzer Daily (in الإنجليزية الأسترالية). 4 February 2020. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "'Criminally overlooked': Canberra named third-best travel city in the world". ABC News (in الإنجليزية الأسترالية). 24 October 2017. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Lonely Planet lists Canberra as one of the world's three hottest destinations". The Guardian (in الإنجليزية). 24 October 2017. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت "EDA ACT Economic Indicators". EDA Australia. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةquickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au - ^ "Canberra blooms: Australia's biggest celebration of spring - People's Daily Online". en.people.cn. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Floriade - the biggest blooming show in Australia". Australian Traveller. 5 September 2014. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Osborne, Tegan (3 April 2016). "What is the Aboriginal history of Canberra?". ABC News (in الإنجليزية الأسترالية). Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ "Ngambri people consider claiming native title over land in Canberra after ACT government apologises". ABC News (in الإنجليزية الأسترالية). 29 April 2023. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

The name 'Canberra' is derived from the name of our people and country: the Ngambri, the Kamberri.

- ^ Selkirk, Henry (1923). "The Origins of Canberra". The Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. 9: 49–78. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ Cambage, Richard Hind (1919). "Part X, The Federal Capital Territory". Notes on the Native Flora of New South Wales. Linnean Society of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- ^ "A Skull Where Once The Native Roamed". The Canberra Times. Vol. 37, no. 10,610. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 9 August 1963. p. 2. Retrieved 23 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Koch, Harold (2009). "The methodology of reconstructing Indigenous placenames: Australian Capital Territory and south-eastern New South Wales". In Koch, Harold; Hercus, Luise (eds.). Aboriginal Placenames: Naming and Renaming the Australian Landscape (PDF). ANU E Press. pp. 155–56.

- ^ Frei, Patricia. "Discussion on the Meaning of 'Canberra'". Canberra History Web. Patricia Frei. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Hull, Crispin (6 February 2009). "European settlement and the naming of Canberra". Canberra – Australia's National Capital. Crispin Hull. Archived from the original on 26 April 2010. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ "Suggested names for Australia's new capital | naa.gov.au". www.naa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Australia For Everyone: Canberra - The Names of Canberra". Australia Guide (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Salvage, Jess (25 August 2016). "The Siting and Naming of Canberra". www.nca.gov.au (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ أ ب [1]

- ^ المناخ في كانبرا

- ^ "Climate: Canberra – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةbom - ^ "Australian heatwave: Canberra and Penrith smash temperature records that stood for 80 years". The Guardian. Australian Associated Press. 4 January 2020. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ "Canberra's warmest winter". abc.net.au. 31 August 2011. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ أ ب "Climate statistics for Australian locations: Canberra Airport Comparison". Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ^ "Australia – Climate of Our Continent". Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "Climate information for Canberra Aero". Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ The Yowie Man, Tim (23 February 2017). "Summer saviour". Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Bureau of Meteorology Australian Capital Territory". Twitter. Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Taylor, John R.; Kossmann, Meinolf; Low, David J.; Zawar-Reza, Peyman (September 2005). "Summertime easterly surges in southeastern Australia: a case study of thermally forced flow" (PDF). Australian Meteorological Magazine (54): 213–223. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Canberra chokes on world's worst air quality as city all but shut down". TheGuardian.com. 3 January 2020. Archived from the original on 4 January 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Climate statistics for Australian locations: Canberra Airport Comparison (1991–2020)". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ "Climate data online (Station number: 070014)". BOM. Retrieved 27 Jun 2025.

- ^ "Climate statistics for Australian locations: Canberra Airport". Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Wigmore 1971, pp. 60-63.

- ^ أ ب Wigmore 1971, p. 67.

- ^ Universal Publishers 2007, pp. 10-120.

- ^ National Capital Development Commission 1988, p. 3.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Wigmore 1971, p. 64.

- ^ Sparke 1988, pp. 1-3.

- ^ Penguin Books Australia 2000, p. 28.

- ^ أ ب ت National Capital Development Commission 1988, p. 17.

- ^ Wigmore 1971, pp. 64-67.

- ^ National Capital Development Commission 1988, p. 4.

- ^ Wigmore 1971, pp. 69-79.

- ^ "Timeline Entries for William Morris Hughes". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ Universal Publishers 2007, pp. 10-60.

- ^ Gibbney 1988, pp. 110-200.

- ^ أ ب Sparke 1988, p. 180.

- ^ "About Weston Creek, Canberra". Weston Creek Community Council. Archived from the original on 8 April 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1987, p. 167.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةmap - ^ أ ب Sparke 1988, pp. 154-155.

- ^ "How to cut through the ACT's planning thicket". The Canberra Times. 2 March 2005. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ أ ب Trail, Jim (9 April 2010). "It's time to review the grand plan for Canberra, says the NCA". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "Grants of leases". ACT Planning & Land Authority. Archived from the original on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ Alexandra, Jason; Norman, Barbara (23 July 2020). "The city as forest - integrating living infrastructure, climate conditioning and urban forestry in Canberra, Australia". Sustainable Earth. 3 (1): 10. Bibcode:2020SuERv...3...10A. doi:10.1186/s42055-020-00032-3. ISSN 2520-8748.

- ^ أ ب "Place name processes". ACT Planning & Land Authority. 11 May 2009. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ "Foreign Embassies in Australia". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ Johnston, Dorothy (September 2000). "Cyberspace and Canberra Crime Fiction". Australian Humanities Review. Archived from the original on 7 January 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت "Environmental care". www.floriadeaustralia.com. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Sustainability issues in Canberra – background". ACT Government. 13 June 2012. Archived from the original on 26 April 2013.

- ^ Corbell, Simon (28 August 2013). "Minister showcases Canberra's sustainability success" (Press release). Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةrenewable - ^ Lawson, Kirsten (29 April 2016). "ACT commits to 100 per cent renewable energy target by 2020: Simon Corbell". The Canberra Times. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016.

- ^ "ACT to be powered by 100pc renewable energy by 2020". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 29 April 2016. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Zero waste" (PDF). Residua. September 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2011.

- ^ Lauer, Sandra (23 May 2007). "Reducing commercial waste going to landfill in Canberra by improving the waste management practices of micro businesses" (PDF). ACT Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2013.

- ^ "Canberra's waste dilemma". CityNews. Canberra. 2 March 2011. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013.

- ^ Allen, Craig (1 March 2010). "No waste". ABC News. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- ^ "Plastic Bag Ban". Canberra Connect. ACT Government. 1 November 2011. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ أ ب Dyett, Kathleen (1 November 2011). "ACT bag ban begins". ABC News. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012.

- ^ "Bin bag sales booming". ABC News. 9 January 2012. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012.

- ^ Nash, Lucy (18 January 2010). "No waste 2010=some waste 2010". 666 ABC Canberra. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015.

- ^ Pryor, Penny (30 October 2011). "Saving money can help save others". The Canberra Times. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةass - ^ "Electorates 2016 election". Elections ACT. 27 April 2016. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ أ ب ت "Canberra". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 29 December 2007. Archived from the original on 9 March 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ أ ب "Fraser". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 29 December 2007. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Past election results". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ "Turbulent 20yrs of self-government". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 11 May 2009. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ Green, Antony. "2016 ACT Election Preview". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ أ ب "Administration of National Land". National Capital Authority. 18 December 2008. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "Capital Works Overview". National Capital Authority. 23 October 2008. Archived from the original on 16 May 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "Maintenance and Operation of Assets". National Capital Authority. 23 October 2008. Archived from the original on 16 May 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ قالب:Cite Legislation AU

- ^ قالب:Cite Legislation AU Schedule 4.

- ^ أ ب Sparke 1988, p. 289.

- ^ أ ب "ACT Representation (House of Representatives) Act 1974 (Cth)". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 16 December 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ^ "ACT elects David Pocock as first independent senator, unseating Liberal Zed Seselja". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 14 June 2022. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Australian Federal Police. 19 November 2009. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ "ACT Policing". Australian Federal Police. 16 March 2010. Archived from the original on 27 January 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "History of the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court". The Supreme Court of the ACT. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ Laverty, Jo (21 May 2009). "The Belconnen Remand Centre". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 29 April 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Kittel, Nicholas (26 November 2008). "ACT prison built to meet human rights obligations". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Canberra Court List". Family Court of Australia. Archived from the original on 3 May 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "Court Listing". ACT Law Courts and Tribunals. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "Crime". Australian Federal Police. ACT Policing. 7 March 2016. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ "4510.0 – Recorded Crime – Victims, Australia, 2016". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 6 July 2017. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Australian Capital Territory". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Australia". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ "CMTED Brief". ACT Government. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "ACT Stats, 2005". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 12 September 2005. Archived from the original on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ أ ب "CMTED Brief". ACT Government. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Janda, Michael (29 October 2009). "House prices surge as rate hike looms". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 4 August 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "It's official: the property market has cooled". Real Estate Institute of Australia. 9 September 2010. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing Australia in Profile A Regional Analysis". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2004. Archived from the original on 2 April 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ Clisby, Meredith (16 January 2014). "ACT still expensive place to live despite fall in rent prices". The Canberra Times. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014.

- ^ All of the land in the ACT land is held by the government.

- ^ s68 allows for an annual increase linked to a Rental Housing CPI index, which is usually significantly higher than CPI. For 2008 this deems an increase up to 10.12% as not excessive on the face of it.

- ^ "CMTED Brief". ACT Government. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "HMAS Harman". Royal Australian Navy. 2008. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ "Fairbairn: Australian War Memorial". Australian War Memorial. 2010. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "RAAF Museum Fairbairn". RAAF Museum. 2009. Archived from the original on 20 November 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "No 34 Squadron". RAAF Museum. 2009. Archived from the original on 20 November 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ Sutherland, Tracy (15 January 2007). "USFTA begins to reap results". Australian Financial Review. Archived from the original on 13 October 2009. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ Sharma, Mahesh (2 April 2008). "HP bids for Tower Software". The Australian. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ Colley, Andrew (2 October 2007). "HP bids for Tower Software". The Australian. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ "Canberra Cyber Security Innovation Node launches". IT Brief. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

المراجع

- Lake Burley Griffin, Canberra: Policy Plan. Canberra: National Capital Development Commission. 1988. ISBN 0-642-13957-1.

- The Penguin Australia Road Atlas. Ringwood, Victoria: Penguin Books Australia. 2000. ISBN 0-670-88980-6.

- UBD Canberra. North Ryde, New South Wales: Universal Publishers. 2007. ISBN 0-7319-1882-7.

- Fitzgerald, Alan (1987). Canberra in Two Centuries: A Pictorial History. Torrens, Australian Capital Territory: Clareville Press. ISBN 0-909278-02-4.

- Gibbney, Jim (1988). Canberra 1913–1953. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-08060-4.

- Gillespie, Lyall (1991). Canberra 1820–1913. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-08060-4.

- Growden, Greg (2008). Jack Fingleton: The Man Who Stood Up To Bradman. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-548-0.

- Sparke, Eric (1988). Canberra 1954–1980. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-08060-4.

- Vaisutis, Justine (2009). Australia. Footscray, Victoria: Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-74179-160-X.

- Wigmore, Lionel (1971). Canberra: History of Australia's National Capital. Canberra: Dalton Publishing Company. ISBN 0-909906-06-8.

- Williams, Dudley (2006). The Biology of Temporary Waters. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-852811-6.

- Leigh, Andrew (3 October 2010). "Canberra is the Best City in Australia". Retrieved 12 August 2012.

وصلات خارجية

كانبرا travel guide from Wikitravel

- WikiSatellite view of Canberra at WikiMapia

- A general Canberra tourist site

- The ACT Government webpage

- Canberra region map – all districts

- ACT Locate – land and planning maps

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأسترالية-language sources (en-au)

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- Australian Statistical Geography Standard 2016 ID different from Wikidata

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing Ngunawal-language text

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages including recorded pronunciations

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ June 2024

- جميع المقالات التي فيها عبارات متقادمة

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 2022

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 2019

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 2016

- كانبرا

- Australian capital cities

- Capitals in Oceania

- Planned capitals

- Cities planned by Walter Burley Griffin

- Populated places established in 1913

- Australian Aboriginal placenames

- Populated places on the Murrumbidgee River

- مدن أستراليا