بريزبين

}}}}

| Brisbane Queensland | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

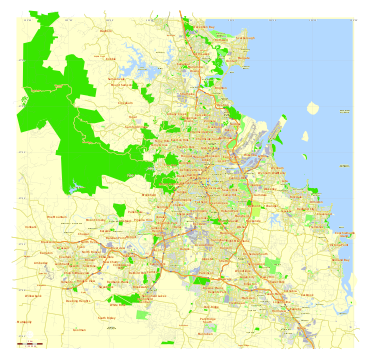

Map of the Greater Brisbane | |||||||||

| Coordinates | 27°28′04″S 153°01′41″E / 27.46778°S 153.02806°E | ||||||||

| Population | 2,780,063 (2024)[1] (3rd) | ||||||||

| • Density | 159/km2 (410/sq mi) [2] (2021 GCCSA) | ||||||||

| Established | مايو 1825 (exact date unknown) [3] | ||||||||

| Elevation | 32 m (105 ft) | ||||||||

| Area | 15٬842 km2 (6٬116٫6 sq mi)[2][4] | ||||||||

| Time zone | AEST (UTC+10:00) | ||||||||

| Location | |||||||||

| LGA(s) | |||||||||

| Region | South East Queensland | ||||||||

| County | Stanley, Canning, Cavendish, Churchill, Ward | ||||||||

| State electorate(s) | 41 divisions | ||||||||

| Federal division(s) | 17 divisions | ||||||||

| |||||||||

بريزبين (Brisbane) هي عاصمة ولاية كوينزلاند، أستراليا، وأكبر مدن الولاية من حيث عدد السكان. بلغ عدد سكانها 1774890 نسمة عام 2003، معظمهم مسيحيين كاثوليك أو بروتستانت. المدينة تقع بالقرب من المحيط الهادي، على ضفاف نهر بريزبين، في السهول بين خليج موريتون وسلسلة جبال گريت دڤايدنگ، جنوب شرق كوينزلاند.[10][11]

سميت المدينة بهذا الاسم تيمناً بالحاكم الاستعماري والفلكي الإسكتلندي السير توماس بريزبين، الذي كان يشغل منصب الحاكم لولاية نيوساوث ويلز بأستراليا. تلقب المدينة محلياً باسم "Brissie". تأسست المدينة عام 1824.

The Moreton Bay penal settlement was founded in 1824 at Redcliffe as a place for secondary offenders from the Sydney colony, but in May 1825 moved to North Quay on the banks of the Brisbane River, so named for the Governor of New South Wales Sir Thomas Brisbane. German Lutherans established the first free settlement of Zion Hill at Nundah in 1838, and in 1859 Brisbane was chosen as Queensland's capital when the state separated from New South Wales. During World War II, the Allied command in the South West Pacific was based in the city, along with the headquarters for General Douglas MacArthur of the United States Army.[12]

Brisbane is a global centre for research and innovation[13][14] and is a transportation hub, being served by large rail, bus and ferry networks, as well as Brisbane Airport and the Port of Brisbane, Australia's third-busiest airport and seaport. A diverse city with over 36% of its metropolitan population being foreign-born, Brisbane is frequently ranked highly in lists of the most liveable cities.[15][16] Brisbane has hosted major events including the 1982 Commonwealth Games, World Expo 88 and the 2014 G20 summit, and will host the 2032 Summer Olympics.[17]

Brisbane is one of Australia's most popular tourist destinations and is Australia's most biodiverse and greenest city.[18] Brisbane's attractions include the Queensland Cultural Centre (which includes the Queensland Art Gallery, the Gallery of Modern Art and the State Library of Queensland), South Bank Parklands, Queen's Wharf, the City Botanic Gardens, the Mount Coot-tha Botanic Gardens, the Brisbane Riverwalk, Moreton Bay and the D'Aguilar National Park. Brisbane's inner-city neighbourhoods are known for their historic Queenslander houses.

اسم المكان

Brisbane is named after the Brisbane River, which in turn was named after Sir Thomas Brisbane, the governor of New South Wales from 1821 to 1825.[19][20][21] The name is derived from the Scottish Gaelic bris, meaning 'to break or smash' and the Old English word ban meaning 'bone'.[22][23] Popular nicknames for Brisbane include Brissie (pronounced "Brizzie"), Brisvegas, and the River City.[24][25]

Part of the Brisbane conurbation is located on traditional indigenous land known also as Meanjin, Meaanjin, Maganjin or Magandjin amongst other spellings.[26] There is a difference of opinion between local traditional owners over the spelling, provenance and pronunciation of indigenous names for Brisbane.[27] Tom Petrie in 1901 stated that the name Meeannjin referred to the area that Brisbane CBD now straddles. Some sources state that the name means 'place shaped as a spike' or 'the spearhead' referencing the shape of the Brisbane River along the area of the Brisbane CBD.[28][29][30][31] A contemporary Turrbal organisation has also suggested it means 'the place of the blue water lilies'.[32] Local Elder Gaja Kerry Charlton posits that Meanjin is based on a European understanding of 'spike', and that the phonetically similar Yagara name Magandjin — after the native tulipwood trees (magan) at Gardens Point — is a more accurate and appropriate Aboriginal name for Brisbane.[33]

Aboriginal groups claiming traditional ownership of the area include the Yagara, Turrbal and Quandamooka peoples.[34][35] Brisbane is home to the land of a number of Aboriginal language groups, primarily the Yagara language group which includes the Turrbal language.[36][37][38][39]

التاريخ

قبل الاستعمار

Aboriginal Australians have lived in coastal South East Queensland for at least 22,000 years, with an estimated population between 6,000 and 10,000 individuals before European settlement in the 1820s.[40][41] Aboriginal groups claiming traditional ownership of the area include the Yagara, Turrbal and Quandamooka peoples.[42][43][44] A website representing a Turrbal culture organisation claims that historical documents suggest that the Turrbal peoples were the only traditional owners of Brisbane when British settlers first arrived.[45]

Archaeological evidence suggests frequent habitation around the Brisbane River, and notably at the site now known as Musgrave Park.[46] The rivers were integral to life and supplied an abundance of food included fish, shellfish, crab, and prawns. Good fishing places became campsites and the focus of group activities. The district was defined by open woodlands with rainforest in some pockets or bends of the Brisbane River.[47]

Being a resource-rich area and a natural avenue for seasonal movement, Meanjin and the surrounding areas acted as a way station for groups travelling to ceremonies and spectacles. The region had several large (200–600 person) seasonal camps, the biggest and most important located along waterways north and south of the current city heart: Barambin or York's Hollow camp (today's Victoria Park) and Woolloon-cappem (Woolloongabba/South Brisbane), also known as Kurilpa. These camping grounds continued to function well into colonial times, and were the basis of European settlement in parts of Brisbane.[48]

القرنان 18 و 19

In 1770, British navigator James Cook sailed through South Passage between the main offshore islands leading to the bay, which he named after James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton, misspelled as "Moreton".[49]

Matthew Flinders initially explored the Moreton Bay area on behalf of the British authorities. On 17 July 1799, Flinders landed at present-day Woody Point, which he named Red Cliff Point after the red-coloured cliffs visible from the bay.[50]

In 1823 the Governor of New South Wales, Sir Thomas Brisbane, gave instructions for the development of a new northern penal settlement, and an exploration party commanded by John Oxley further explored Moreton Bay in November 1823.[51]

Oxley explored the Brisbane River as far as Goodna, 20 km (12 mi) upstream from the present-day central business district of Brisbane.[51] He also named the river after the governor of the time.[51] Oxley also recommended Red Cliff Point for the new colony, reporting that ships could land at any tide and easily get close to the shore.[52] The convict settlement party landed in Redcliffe on 13 September 1824 formally establishing the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement that would become Brisbane. The party was under the command of Lieutenant Henry Miller and consisted of 14 soldiers (some with wives and children) and 29 convicts. However, the settlers abandoned this site after a year and moved to an area on the Brisbane River now known as North Quay, 28 km (17 mi) south, which offered a more reliable water-supply. The newly selected Brisbane region was plagued by mosquitoes at the time.[53]

After visiting the Redcliffe settlement, Sir Thomas Brisbane then travelled 45 km (28 mi) up the Brisbane River in December 1824. Governor Brisbane stayed overnight in a tent and often landed ashore, thus bestowing upon the future Brisbane City the distinction of being the only Australian capital city visited by its namesake.[54] Chief Justice Forbes gave the new settlement the name of Edenglassie before it was named Brisbane.[55][need quotation to verify]

The penal settlement under the control of Captain Patrick Logan (Commandant from 1826 to 1830) flourished, with the numbers of convicts increasing dramatically from around 200 to over 1,000 men.[56] He developed a substantial settlement of brick and stone buildings, complete with school and hospital. He formed additional outstations and made several important journeys of exploration. Logan became infamous for his extreme use of the cat o' nine tails on convicts. The maximum allowed limit of lashes was 50; however, Logan regularly applied sentences of 150 lashes.[56]

During this period raids on maize fields were conducted by local Aboriginal groups in the Corn Field Raids of 1827-1828. These groups destroyed and plundered the maize fields in South Bank and Kangaroo Point, with the possible motive of extracting compensation from the settlers or warning them not to expand beyond their current area.[57][58]

Between 1824 and 1842, almost 2,400 men and 145 women were detained at the Moreton Bay convict settlement under the control of military commandants.[59] However, non-convict European settlement of the Brisbane region commenced in 1838 and the population grew strongly thereafter, with free settlers soon far outstripping the convict population.[60] German missionaries settled at Zions Hill, Nundah as early as 1837, five years before Brisbane was officially declared a free settlement. The band consisted of ministers Christopher Eipper (1813–1894), Carl Wilhelm Schmidt, and lay missionaries Haussmann, Johann Gottried Wagner, Niquet, Hartenstein, Zillman, Franz, Rode, Doege and Schneider.[61] They were allocated 260 hectares and set about establishing the mission, which became known as the German Station.[62] Later in the 1860s many German immigrants from the Uckermark region in Prussia as well as from other German regions settled in the areas of Bethania, Beenleigh and the Darling Downs. These immigrants were selected and assisted through immigration programs established by Rev Dr John Dunmore Lang and Johann Christian Heussler and were offered free passage, good wages, and selections of land.[63][64]

Scottish immigrants from the ship Fortitude arrived in Brisbane in 1849, enticed by Lang on the promise of free land grants. Denied land, the immigrants set up camp in York's Hollow waterholes in the vicinity of today's Victoria Park, Herston, Queensland. A number of the immigrants moved in and settled the suburb, naming it Fortitude Valley after the ship on which they arrived.[65]

Free settlers entered the area from 1835,[citation needed] and by the end of 1840, Robert Dixon had begun work on the first plan of Brisbane Town, in anticipation of future development.[66] The Roman Catholic church erected the Pugin Chapel in 1850, to the design by the gothic revivalist Augustus Pugin. Letters patent dated 6 June 1859, proclaimed by Sir George Ferguson Bowen on 10 December 1859, separated Queensland from New South Wales, whereupon Bowen became Queensland's first governor,[67] with Brisbane chosen as the capital.[68] Old Government House was constructed in 1862 to house Sir George Bowen's family, including his wife, the noblewoman Diamantina, Lady Bowen di Roma. During the tenure of Lord Lamington, Old Government House was the likely site of the origin of Lamingtons.[69]

During the War of Southern Queensland, Indigenous attacks occurred across the city, committing robberies and terrorising unarmed residents.[70][71] Reprisal raids took place against the Duke of York's clan in Victoria Park in 1846 and 1849 by British soldiers of the 11th Regiment, however the clan had been wrongfully targeted as the attacks on Brisbane had not been committed by the Turrbal themselves but other tribes farther north.[72][73] In 1855, Dundalli, a prominent leader during the conflict, was captured and executed by hanging at the present site of the GPO.

In 1862, the first sugarcane plantation in Queensland was established near Brisbane by Captain Louis Hope and John Buhôt.[citation needed]

In 1864, the Great Fire of Brisbane burned through the central parts of the city, destroying much of Queen Street.[74] The 1860s were a period of economic and political turmoil leading to high unemployment, in 1866 hundreds of impoverished workers convened a meeting at the Treasury Hotel, with a cry for "bread or blood", rioted and attempted to ransack the Government store.[75]

The City Botanic Gardens were originally established in 1825 as a farm for the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement, and were planted by convicts in 1825 with food crops to feed the prison colony.[76] In 1855, several acres was declared a Botanic Reserve under the Superintendent Walter Hill, a position he held until 1881.[77][78] Some trees planted in the Gardens were among the first of their species to be planted in Australia, including the jacaranda and poinciana.[79]

Charles Tiffin was appointed as Queensland Government Architect in 1859, and pursued an intellectual policy in the design of public buildings based on Italianate and Renaissance revivalism, with such buildings as Government House, the Department of Primary Industries Building in 1866, and the Queensland Parliament built in 1867. The 1880s brought a period of economic prosperity and a major construction boom in Brisbane, that produced an impressive number of notable public and commercial buildings. John James Clark was appointed Queensland Government Architect in 1883, and continuing in Tiffin's design for public buildings, asserted the propriety of the Italian Renaissance, drawing upon typological elements and details from conservative High Renaissance sources. Building in this trace of intellectualism, Clark designed the Treasury Building in 1886, and the Yungaba Immigration Centre in 1885.[80] Other major works of the era include Customs House in 1889, and the Old Museum Building completed in 1891.

Fort Lytton was constructed in 1882 at the mouth of the Brisbane river, to protect the city against foreign colonial powers such as Russia and France, and was the only moated fort ever built in Australia.

The city's slum district of Frog's Hollow, named so for its location being low-lying and swampy, was both the red light district of colonial Brisbane and its Chinatown, and was the site of prostitution, sly grog, and opium dens. In 1888, Frog's Hollow was the site of anti-Chinese riots, where more than 2000 people attacked Chinese homes and businesses.[81]

In 1893 Brisbane was affected by the Black February flood, when the Brisbane River burst its banks on three occasions in February and again in June in the same year, with the city receiving more than a year's rainfall during February 1893, leaving much of the city's population homeless. In 1896, the Brisbane river saw its worst maritime disaster with the capsize of the ferry Pearl, between the 80–100 people on board there were only 40 survivors.[82]

20th century

When the colonies federated in 1901, celebrations were held in Brisbane to mark the event, with a triumphal arch erected in Queen Street. In May that year, the Duke of Cornwall and York (later King George V) laid the foundation stone of St John's Cathedral, one of the great cathedrals of Australia. The University of Queensland was founded in 1909 and first sited at Old Government House, which became vacated as the government planned for a larger residence. Fernberg House, built in 1865, became the temporary residence in 1910, and later made the permanent government house.

In 1912, Tramway employees were stood down for wearing union badges which sparked Australia's first general strike, the 1912 Brisbane General Strike, which became known as Black Friday, for the savagery of the police baton charges on crowds of trade unionists and their supporters. In 1917, during World War I, the Commonwealth Government conducted a raid on the Queensland Government Printing Office, with the aim of confiscating copies of Hansard that covered debates in the Queensland Parliament where anti-conscription sentiments had been aired.

Russian immigration took place in the years 1911–1914. Many were radicals and revolutionaries seeking asylum from tsarist political repression in the final chaotic years of the Russian Empire; considerable numbers were Jews escaping state-inspired pogroms. They had fled Russia via Siberia and Northern China, most making their way to Harbin, in Manchuria, then taking passage from the port of Dalian to Townsville or Brisbane, the first Australian ports of call.[83]

Following the First World War, conflict arose between returned servicemen of the First Australian Imperial Force and socialists along with other elements of society that the ex-servicemen considered to be disloyal toward Australia.[84] Over the course of 1918–1919, a series of violent demonstrations and attacks known as the Red Flag riots, were waged throughout Brisbane. The most notable incident occurred on 24 March 1919, when a crowd of about 8,000 ex-servicemen clashed violently with police who were preventing them from attacking the Russian Hall in Merivale Street, South Brisbane, which was known as the Battle of Merivale Street. Over 20 small municipalities and shires were amalgamated in 1925 to form the City of Brisbane, governed by the Brisbane City Council.[85] A significant year for Brisbane was 1930, with the completion of Brisbane City Hall, then the city's tallest building and the Shrine of Remembrance, in ANZAC Square, which has become Brisbane's main war memorial.[86]

These historic buildings, along with the Story Bridge which opened in 1940, are key landmarks that help define the architectural character of the city. Following the death of King George V in 1936, Albert square was widened to include the area which had been Albert Street, and renamed King George Square in honour of the King. An equestrian statue of the king and two Bronze Lion sculptures were unveiled in 1938.[citation needed]

In 1939, armed farmers marched on the Queensland Parliament and stormed the building in an attempt to take hostage the Queensland Government led by Labor Premier William Forgan Smith, in an event that became known as the Pineapple rebellion.[87]

During World War II, Brisbane became central to the Allied campaign, since it was the northernmost city with adequate communications facilities. From July 1942 to September 1944, AMP Building (now called MacArthur Central) was used as the headquarters for South West Pacific Area under General MacArthur. MacArthur had previously rejected use of the University of Queensland complex as his headquarters, as the distinctive bends in the river at St Lucia could have aided enemy bombers. Also used as a headquarters by the American troops during World War II was the T & G Building.[88] About one million US troops passed through Australia during the war, as the primary co-ordination point for the South West Pacific.[89] Wartime Brisbane was defined by the racial segregation of African American servicemen, prohibition and sly grog, crime, and jazz ballrooms.[90][91] It became Australia's third-most populous city in the post-war era, overtaking Adelaide in the early 1940s.[92]

In 1942, Brisbane was the site of a violent clash between visiting US military personnel and Australian servicemen and civilians, which resulted in one death and hundreds of injuries. This incident became known colloquially as the Battle of Brisbane.[93]

Post-war Brisbane had developed a big country town stigma, an image the city's politicians and marketers were very keen to remove.[94] In the late 1950s, an anonymous poet known as The Brisbane Bard generated much attention to the city which helped shake this stigma.[95][96] In 1955, Wickham Terrace was the site of a terrorist incident involving shootings and bombs, by the German immigrant Karl Kast. Despite steady growth, Brisbane's development was punctuated by infrastructure problems. The state government under Joh Bjelke-Petersen began a major program of change and urban renewal, beginning with the central business district and inner suburbs. Trams in Brisbane were a popular mode of public transport until the network was closed in 1969, in part the result of the Paddington tram depot fire.

Between 1968 and 1987, Queensland was governed by Bjelke-Petersen, whose government was characterised by social conservatism, police corruption, and the brutal suppression of protest and has been described as a police state.[97] However, during this time Brisbane developed a counterculture focused on the University of Queensland, street marches and Brisbane punk rock music.[citation needed]

In 1971, the touring Springboks were to play against the Australian Rugby team. This was met with plans for protests due to the growing international and local opposition to apartheid in South Africa. However, before their arrival Bjelke-Petersen declared a state of emergency for a month, citing the importance of the tour.[98] This did not stop the protest however with violent clashes between protestors and police erupting when several hundred demonstrators assembled outside a Brisbane motel on Thursday, 22 July 1971, where the Springbok team was staying. A second protest saw a large number of demonstrators assembled once more outside the Tower Mill Motel and after 15 minutes of peaceful protest, a brick was thrown into the motel room and police took action to clear the road and consequently disproportionate violence was used against demonstrators.[99]

In the lead up to the 1980s Queensland fell subject to many forms of censorship. In 1977 things had escalated from prosecutions and book burnings, under the introduction of the Literature Board of Review, to a statewide ban on protests and street marches. In September 1977 the Queensland Government introduced a ban on all street protests, resulting in a statewide civil liberties campaign of defiance.[100] This saw two thousand people arrested and fined, with another hundred being imprisoned, at a cost of almost five million dollars to the State Government.[101] Bjelke-Petersen publicly announced on 4 September 1977 that "the day of the political street march is over ... Don't bother to apply for a permit. You won't get one. That's government policy now."[102] In response to this, protesters came up with the idea of Phantom Civil Liberties Marches where protesters would gather and march until the police and media arrived. They would then disperse, and gather together again until the media and police returned, repeating the process over and over again.[103]

The end of the Bjelke-Petersen era began with the Fitzgerald Inquiry of 1987 to 1989, a judicial inquiry presided over by Tony Fitzgerald investigating Queensland Police corruption. The inquiry resulted in the resignation of Premier Bjelke-Petersen, the calling of two by-elections, the jailing of three former ministers and the Police Commissioner Terry Lewis (who also lost his knighthood). It also contributed to the end of the National Party of Australia's 32-year run as the governing political party in Queensland.[citation needed]

In 1973, the Whiskey Au Go Go nightclub in the city's entertainment district, was firebombed that resulted in 15 deaths, in what is one of Australia's worst mass killings.[104] The 1974 Brisbane flood was a major disaster which temporarily crippled the city, and saw a substantial landslip at Corinda. During this era, Brisbane grew and modernised, rapidly becoming a destination of interstate migration. Some of Brisbane's popular landmarks were lost to development in controversial circumstances, including the Bellevue Hotel in 1979 and Cloudland in 1982. Major public works included the Riverside Expressway, the Gateway Bridge, and later, the redevelopment of South Bank. Starting with the monumental Robin Gibson-designed Queensland Cultural Centre, with the first stage the Queensland Art Gallery completed in 1982, the Queensland Performing Arts Centre in 1985, and the Queensland Museum in 1986.[citation needed]

Brisbane hosted the 1982 Commonwealth Games and World Expo 88. These events were accompanied by a scale of public expenditure, construction, and development not previously seen in the state of Queensland.[105][106] Brisbane's population growth far exceeded the national average in the last two decades of the 20th century, with a high level of interstate migration from Victoria and New South Wales. In the late 1980s Brisbane's inner-city areas were struggling with economic stagnation, urban decay and crime which resulted in an exodus of residents and business to the suburban fringe, in the early 1990s the city undertook an extensive and successful urban renewal of the Woolstore precinct as well as the development of South Bank Parklands.[107]

21st century

Brisbane was impacted by major floods in January 2011 and February 2022. The Brisbane River did not reach the same height as the previous 1974 flood on either occasion, but caused extensive disruption and damage to infrastructure.[108][109]

The Queensland Cultural Centre has been expanded, with the completion of the State Library and the Gallery of Modern Art in 2006, and the Kurilpa Bridge in 2009, which is the world's largest hybrid tensegrity bridge.[110] Brisbane also hosted major international events including the final Goodwill Games in 2001, the Rugby League World Cup final in 2008 and again in 2017, as well as the 2014 G20 Brisbane summit.

Population growth has continued to be among the highest of the Australian capital cities in the first two decades of the 21st century, and a number of major infrastructure projects have been completed or are under construction, including the Howard Smith Wharves, Roma Street Parklands, Brisbane Riverwalk, Queen's Wharf hotel and casino precinct, Brisbane International Cruise Terminal, the Clem Jones, Airport Link, and Legacy Way road tunnels, and the Airport, Springfield, Redcliffe Peninsula and Cross River Rail commuter railway lines.

Furthermore, the city has seen a renewed construction boom, with the rise of many new skyscrapers and apartment buildings throughout the city, though largely concentrated in the CBD and inner suburbs.[111][112] Some of these new buildings include Riparian Plaza, Aurora Tower, Brisbane Square, Soleil, 111 Eagle Street, Infinity, 1 William Street, Brisbane Skytower, Brisbane Quarter and 443 Queen Street.

Brisbane will also host the 2032 Summer Olympics and 2032 Summer Paralympics.[113][114]

Geography and environment

Brisbane is in the southeast corner of Queensland. The city is centred along the Brisbane River, and its eastern suburbs line the shores of Moreton Bay, a bay of the Coral Sea. The greater Brisbane region is on the coastal plain east of the Great Dividing Range, with the Taylor and D'Aguilar ranges extending into the metropolitan area. Brisbane's metropolitan area sprawls along the Moreton Bay floodplain between the Gold and Sunshine coasts, approximately from Caboolture in the north to Beenleigh in the south, and across to Ipswich in the south west.

The Brisbane River is a wide tidal estuary and its waters throughout most of the metropolitan area are brackish and navigable. The river takes a winding course through the metropolitan area with many steep curves from the southwest to its mouth at Moreton Bay in the east. The metropolitan area is also traversed by several other rivers and creeks including the North Pine and South Pine rivers in the northern suburbs, which converge to form the Pine River estuary at Bramble Bay, the Caboolture River further north, the Logan and Albert rivers in the south-eastern suburbs, and tributaries of the Brisbane River including the Bremer River in the south-western suburbs, Breakfast Creek in the inner-north, Norman Creek in the inner-south, Oxley Creek in the south, Bulimba Creek in the inner south-east and Moggill Creek in the west. The city is on a low-lying floodplain,[115] with the risk of flooding addressed by various state and local government regulations and plans.[116]

The waters of Moreton Bay are sheltered from large swells by Moreton, Stradbroke and Bribie islands, so whilst the bay can become rough in windy conditions, the waves at the Moreton Bay coastline are generally not surfable. Unsheltered surf beaches lie on the eastern coasts of Moreton, Stradbroke and Bribie islands and on the Gold Coast and Sunshine Coast to the south and north respectively. The southern part of Moreton Bay also contains smaller islands such as St Helena Island, Peel Island, Coochiemudlo Island, Russell Island, Lamb Island and Macleay Island.

The city of Brisbane is hilly.[117] The urban area, including the central business district, are partially elevated by spurs of the Herbert Taylor Range, such as the summit of Mount Coot-tha, reaching up to 300 m (980 ft) and Enoggera Hill. The D'Aguilar National Park, encompassing the D'Aguilar Range, bounds the north-west of Brisbane's built-up area, and contains the taller peaks of Mount Nebo, Camp Mountain, Mount Pleasant, Mount Glorious, Mount Samson and Mount Mee. Other prominent rises in Brisbane are Mount Gravatt, Toohey Mountain, Mount Petrie, Highgate Hill, Mount Ommaney, Stephens Mountain, and Whites Hill, which are dotted across the city.

Much of the rock upon which Brisbane is located is the characteristic Brisbane tuff, a form of welded ignimbrite,[118] which is most prominently found at the Kangaroo Point Cliffs at Kangaroo Point and the New Farm Cliffs on the Petrie Bight reach of the Brisbane River. The stone was used in the construction of historical buildings such as the Commissariat Store and Cathedral of St Stephen, and the roadside kerbs in inner areas of Brisbane are still manufactured of Brisbane tuff.

Ecology

Brisbane is located within the South East Queensland biogeographic region, and is home to numerous Eucalyptus varieties. Common trees in Brisbane include the Moreton Bay fig, an evergreen banyan with large buttress roots named for the region which are often lit with decorative lights in the inner city, as well as the jacaranda, a subtropical tree native to South America which line many avenues and parks and bloom with purple flowers during October.[119] Other trees common to the metropolitan area include Moreton Bay chestnut, broad-leaved paperbark, poinciana, weeping lilli pilli and Bangalow palm. Some of the banks of the Brisbane River and Moreton Bay are home to mangrove wetlands. The red poinsettia is the original official floral emblem of Brisbane, however it is native to Central America.[120] An additional floral emblem, the Brisbane wattle, which is native to the Brisbane area, was added in 2023.[121]

Brisbane is home to numerous bird species, with common species including rainbow lorikeets, kookaburras, galahs, Australian white ibises, Australian brushturkeys, Torresian crows, Australian magpies and noisy miners. Common reptiles include common garden skinks, Australian water dragons, bearded dragons and blue-tongued lizards. Common ringtail possums and flying foxes are common in parks and yards throughout the city, as are common crow butterflies, blue triangle butterflies, golden orb-weaver spiders and St Andrew's Cross spiders. The Brisbane River is home to many fish species including yellowfin bream, flathead, Australasian snapper, and bull sharks. The waters of Moreton Bay are home to dugongs, humpback whales, dolphins, mud crabs, soldier crabs, Moreton Bay bugs and numerous shellfish species. The koala and the graceful tree frog are the official faunal emblems of Brisbane, however both are increasingly less common due to the effects of increased development and climate-change.[120][122]

Climate

Brisbane has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfa)[123] with hot, wet summers and moderately drier, mild winters.[124][125] Brisbane experiences an annual mean minimum of 16.6 °C (62 °F) and mean maximum of 26.6 °C (80 °F), making it Australia's second-hottest capital city after Darwin.[126] Seasonality is not pronounced, and average maximum temperatures of above 26 °C (79 °F) persist from October through to April.

Due to its proximity to the Coral Sea and a warm ocean current, Brisbane's overall temperature variability is somewhat less than most Australian capitals. Summers are long, hot, and wet, but temperatures only occasionally reach 35 °C (95 °F) or more. Eighty percent of summer days record a maximum temperature of 27 إلى 33 °C (81 إلى 91 °F). Winters are short and warm, with average maximums of about 22 °C (72 °F); maximum temperatures below 20 °C (68 °F) are rare.

The city's highest recorded temperature was 43.2 °C (109.8 °F) on Australia Day 1940 at the Brisbane Regional Office,[127] with the highest temperature at the current station being 41.7 °C (107.1 °F) on 22 February 2004;[128] but temperatures above 38 °C (100 °F) are uncommon. On 19 July 2007, Brisbane's temperature fell below the freezing point for the first time since records began, registering −0.1 °C (31.8 °F) at the airport station.[129] The city station has never dropped below 2 °C (36 °F),[130] with the average coldest night during winter being around 6 °C (43 °F), however locations in the west of the metropolitan area such as Ipswich have dropped as low as −5 °C (23 °F) with heavy ground frost.[131]

In 2009, Brisbane recorded its hottest winter day (from June to August) at 35.4 °C (95.7 °F) on 24 August;[132] The average July day however is around 22 °C (72 °F) with sunny skies and low humidity, occasionally as high as 27 °C (81 °F), whilst maximum temperatures below 18 °C (64 °F) are uncommon and usually associated with brief periods of cloud and winter rain.[130] The highest minimum temperature ever recorded in Brisbane was 28.0 °C (82.4 °F) on 29 January 1940 and again on 21 January 2017, whilst the lowest maximum temperature was 10.2 °C (50.4 °F) on 12 August 1954.[127]

Sleet or snow is exceptionally rare in Brisbane. The Bureau of Meteorology has only three official records of snow in Brisbane: June 1927, June 1932 (witnessed by seven people), and September 1958 (light flakes were seen by four people at 5:15pm in Moorooka, Wooloowin, Bowen Hills and Taringa). Unofficial eports exist of earlier snowfalls, such as follows from July 1882:[اقتباس بدون مصدر] "The snow was most noticeable in Woolloongabba, but in Stanley Street, South Brisbane it was sufficiently heavy to allow of people wiping it from their clothing. "In the vicinity of the museum the fall was, though very slight, plainly noticeable. "It is said that snow fell in this city 35 years ago, and the summer following the period of the fall was remarkable for its excessive heat."

Annual precipitation is ample. From November to March, thunderstorms are common over Brisbane, with the more severe events accompanied by large damaging hail stones, torrential rain and destructive winds. On an annual basis, Brisbane averages 124 clear days, with overcast skies more common in the warmer months.[133] Dewpoints in the summer average at around 20 °C (68 °F); the apparent temperature exceeds 30 °C (86 °F) on almost all summer days.[130] Brisbane's wettest day occurred on 21 January 1887, when 465 ميليمتر (18.3 in) of rain fell on the city, the highest maximum daily rainfall of Australia's capital cities. The wettest month on record was February 1893, when 1،025.9 ميليمتر (40.39 in) of rain fell, although in the last 30 years the record monthly rainfall has been a much lower 479.8 ميليمتر (18.89 in) from December 2010. Very occasionally a whole month will pass with no recorded rainfall, the last time this happened was August 1991.[127] The city has suffered four major floods since its founding, in February 1893, January 1974 (partially a result of Cyclone Wanda), January 2011 (partially a result of Cyclone Tasha) and February 2022.

Brisbane is within the southern reaches of the tropical cyclone risk zone. Full-strength tropical cyclones rarely affect Brisbane, but occasionally do so. The biggest risk is from ex-tropical cyclones, which can cause destructive winds and flooding rains.[134]

The average annual temperature of the sea ranges from 21.0 °C (69.8 °F) in July to 27.0 °C (80.6 °F) in February.[135]

| بيانات المناخ لـ Brisbane (1999–2024 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| القصوى القياسية °س (°ف) | 40.0 (104.0) |

41.7 (107.1) |

37.9 (100.2) |

33.7 (92.7) |

30.7 (87.3) |

29.0 (84.2) |

29.1 (84.4) |

35.4 (95.7) |

37.0 (98.6) |

38.7 (101.7) |

38.9 (102.0) |

41.2 (106.2) |

41.7 (107.1) |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °س (°ف) | 30.4 (86.7) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.2 (84.6) |

27.2 (81.0) |

24.5 (76.1) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.0 (71.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

25.7 (78.3) |

27.1 (80.8) |

28.3 (82.9) |

29.6 (85.3) |

26.7 (80.1) |

| المتوسط اليومي °س (°ف) | 26.1 (79.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

24.8 (76.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

19.2 (66.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

16.3 (61.3) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.8 (67.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

23.6 (74.5) |

25.1 (77.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °س (°ف) | 21.7 (71.1) |

21.5 (70.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

17.4 (63.3) |

13.9 (57.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

10.5 (50.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

13.9 (57.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.8 (65.8) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

| الصغرى القياسية °س (°ف) | 17.0 (62.6) |

16.5 (61.7) |

12.2 (54.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

2.6 (36.7) |

4.1 (39.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

14.0 (57.2) |

2.6 (36.7) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار mm (inches) | 141.1 (5.56) |

181.9 (7.16) |

129.3 (5.09) |

60.5 (2.38) |

69.8 (2.75) |

56.9 (2.24) |

30.4 (1.20) |

34.6 (1.36) |

29.7 (1.17) |

85.8 (3.38) |

100.1 (3.94) |

140.0 (5.51) |

1٬048٫2 (41.27) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 8.8 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 7.2 | 7.9 | 8.9 | 82.8 |

| متوسط الرطوبة النسبية بعد الظهر (%) | 57 | 59 | 57 | 54 | 49 | 52 | 44 | 43 | 48 | 51 | 56 | 57 | 52 |

| Mean monthly ساعات سطوع الشمس | 267 | 235 | 233 | 237 | 239 | 198 | 239 | 270 | 267 | 270 | 273 | 264 | 2٬989 |

| نسبة السطوع المحتمل للشمس | 63 | 65 | 62 | 69 | 71 | 63 | 73 | 78 | 74 | 68 | 67 | 62 | 68 |

| متوسط مؤشر فوق البنفسجية | 13 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 9 |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[136] | |||||||||||||

الحكم

الاقتصاد

الديمغرافيا

| Significant overseas born populations[137] | |

| Country of Birth | Population (2006) |

|---|---|

| المملكة المتحدة | 95,199 |

| نيوزيلندا | 72,811 |

| جنوب أفريقيا | 12,796 |

| Vietnam | 11,922 |

| People's Republic of China | 11,447 |

| Philippines | 9,920 |

| ألمانيا | 8,615 |

| الهند | 7,564 |

| ماليزيا | 6,682 |

| Fiji | 6,762 |

| إيطاليا | 6,743 |

| الولايات المتحدة | 6,083 |

| Croatia | 6,059 |

| Hong Kong | 6,039 |

| كوريا الجنوبية | 4,870 |

| لبنان | 3,250 |

مواقع المعالم

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ "Regional population, 2023–24 financial year". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 26 March 2023. Retrieved 12 April 2025.

- ^ أ ب "2021 Greater Brisbane, Census Community Profiles". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Uncovering the secrets behind the City of Brisbane's settlement 190 years ago". ABC News. 13 May 2015. Archived from the original on 3 August 2024. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ "What is the greater Brisbane area?" Archived 11 أكتوبر 2022 at the Wayback Machine, brisbanetour.com.au

- ^ "Great Circle Distance from between Brisbane and Sydney". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between Brisbane and Canberra". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between Brisbane and Melbourne". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between Brisbane and Adelaide". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between Brisbane and Perth". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ "Brisbane City Council Local Government Area Map" (PDF). Electoral Commission of Queensland. Retrieved 2024-09-30.

- ^ "About Brisbane – Visit Brisbane". Visit Brisbane. 16 January 2022. Archived from the original on 16 January 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ "South West Pacific campaign". Queensland World War II Historic Places. Queensland Government. 30 June 2014. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ "Brisbane: A hub for innovation and the gateway to Asia". Business Chief. 19 May 2020. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Brisbane". startupgenome. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ "2016 Census Community Profiles: Greater Brisbane". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 23 October 2017. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ "Announced: Melbourne Remains the World's Second Most Liveable City". Broadsheet. 4 September 2019. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ "Brisbane wakes as Olympics 2032 city after IOC's landslide vote of confidence". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 22 July 2021. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Brisbane. Clean, Green, Sustainable". brisbane.qld.gov.au (in الإنجليزية). 15 February 2024.

- ^ Brisbane Australia.com. "Brisbane River History". Brisbane Australia.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

It was then that he named the river after Sir Brisbane, the Governor of NSW.

- ^ "Go back in time when Brisbane was named after a river". Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2025-03-09.

200 years ago when the explorer John Oxley visited Moreton Bay in 1823, he named the river Brisbane in honour of the then Governor of New South Wales, Sir Thomas Makdougall Brisbane (1773-1860). Later, in 1825, a settlement on its banks to house Sydney's most unruly convicts was called Brisbane.

- ^ Heydon, J. D. (1966). "Sir Thomas Makdougall Brisbane (1773–1860)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 1. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 23 July 2024.

The city of Brisbane, Queensland's capital since 1859, was founded as a convict settlement in 1824, and it and its river were named for the governor at the suggestion of the explorer Oxley, the first European to survey the area.

- ^ "Brisbane Surname Meaning & Brisbane Family History at Ancestry.com®". www.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2024-07-23.

- ^ Moffet, Rodger (17 October 2021). "Clan Brisbane History". ScotClans. Archived from the original on 14 June 2024. Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ Scott, Noel; Clark, Stephen (2006). "The Development and Tracking of a Branding Campaign for Brisbane". In Prideaux, Bruce; Moscardo, Gianna; Laws, Eric (eds.). Managing Tourism and Hospitality Services: Theory and International Applications. CABI. ISBN 9781845930158. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Asher, Morris (31 July 1907). "Brisbane: The Queen City of the North". Trove. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Calligeros, Marissa (2024-09-30). "And it will be called ... Albert Street station". Brisbane Times (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ "Community shapes station name". statements.qld.gov.au (in الإنجليزية). Queensland Government. 30 September 2024. Archived from the original on 27 October 2024.

- ^ "Meanjin: exploring the Traditional Place name of Brisbane". Australia Post (in الإنجليزية). 2023-07-14.

- ^ "Our Shared Vision: Living in Brisbane in 2026" (PDF). Brisbane City Council. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-27.

- ^ "Jenine Godwin-Thompson". christinejoycuration.com.au (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2024-12-13.

- ^ McIlwraith, Phoebe (2024-01-24). "A Guide To The Aboriginal / First Nations Name For Every Major Australian City". Pedestrian (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ Turrbal Dippil. "Our Story". Turrbal (in الإنجليزية الأسترالية). Archived from the original on 7 December 2020. Retrieved 2023-10-25.

- ^ Charlton, Gaja Kerry (15 June 2023). "Makunschan, Meeanjan, Miganchan, Meanjan, Magandjin". Meanjin. Archived from the original on 6 February 2024. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

In 1843, [ Ludwig Leichhardt ] was given two names: Makandschin from an original Brisbane man and Megandsin from an original speaker from a different country... Meston listed Magoo-jin then Magandjin, based on Magan, the name of the Tulipwood tree, from elderly Goori [Aboriginal] speakers who asserted they were 'Brisbane natives'... From a Goori knowledge base the names based on the Tulipwood tree fits best for the original Goori name. The suffix -djin indicates plural, e.g. people, district, river. The Migan-dar-gu-n (Mi'andjan) version describes the use of a sharp tool, possibly ground being dug up, likely the first convict garden, which the Petrie map shows multiplied across the whole of the promontory. Another explanation of this name is 'land shaped like a spike'. Both these are based on Dugai [European] activity and Dugai lens... Magandjin fits as the original word for an area of what is now called Brisbane. Migandjan refers to digging the ground—either gardens or buildings. However, the term Migandjan spread. As demonstrated, language repatriation is a work in progress.

- ^ National Native Title Tribunal. "Yagara/YUgarapul People (QC2011/008)". National Native Title Tribunal. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ National Native Title Tribunal. "Quandamooka People #4 (QC2014/006)". National Native Title Tribunal. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ Crump, Desmond (16 March 2015). "Aboriginal languages of the Greater Brisbane Area". State Library of Queensland. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ "E23: Yuggera". Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Collection. n.d. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ "E86: Turrbal". Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Collection. n.d. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ Ridley, WM (1866). Kamilaroi, Dippil, and Turrubul: Languages Spoken by Australian Aborigines (in الإنجليزية الأسترالية). Sydney: New South Wales Government Printing Office. p. 61.

- ^ Archibald Meston. "Aboriginal Indigeneous [[[كذا|ك]]] Tribes of Brisbane and Moreton Bay". Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help)CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Tony Moore (17 May 2012). "The indigenous history of Musgrave Park". Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Anonymous (26 July 2019). "E23: Yuggera". collection.aiatsis.gov.au (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Anonymous (26 July 2019). "E86: Turrbal". collection.aiatsis.gov.au (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Anonymous (26 July 2019). "E21: Moondjan". collection.aiatsis.gov.au (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "Welcome to Country Ceremony". Turrbal Dippil. n.d. Archived from the original on 7 January 2023. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ Ros Kidd. "Aboriginal History of the Princess Alexandra Hospital Site". Diamantina Health Care Museum Association Inc. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Jones, Ryan. "Indigenous Aboriginal Sites of Southside Brisbane | Mapping Brisbane History". mappingbrisbanehistory.com.au (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Kerkhove, Ray (2015). Aboriginal Campsites of Greater Brisbane: An Historical Guide. Salibury: Boolarong Press.

- ^ "Moreton Bay". Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ "Redcliffe". The Sydney Morning Herald. 8 February 2004. Archived from the original on 23 May 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- ^ أ ب ت "John Oxley Governor Report". Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ^ Potter, Ron. "Place Names of South East Queensland". Piula Publications. Archived from the original on 23 May 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- ^ Irving, Robert (1998). Reader's Digest Book of Historic Australian Towns. Reader's Digest (Australia). p. 70. ISBN 0-86449-271-5.

- ^ "Sir Thomas 28 miles up the Brisbane River". MOST Brisbane. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ compiled by Royal Automobile Club of Queensland. (1980). Seeing South-East Queensland (2 ed.). RACQ. p. 7. ISBN 0-909518-07-6.

- ^ أ ب "Patrick Logan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ "Corn Fields Raids 1827–1828". Frontier Battle. 17 July 2017. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ Evans, Raymond (2008). "On the Utmost Verge: Race and Ethnic Relations at Moreton Bay, 1799–1842". Queensland Review. 15 (1): 14. doi:10.1017/S1321816600004542. ISSN 1321-8166. S2CID 147375003. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ Harrison, Jennifer (16 March 2016). "Moreton Bay convict settlement". Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ "About Redcliffe". Redcliffe City Council. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- ^ Lybaek, Lena; Konrad Raiser; Stefanie Schardien (2004). Gemeinschaft der Kirchen und gesellschaftliche Verantwortung. Münster: LIT. p. 114. ISBN 978-3-8258-7061-4.

- ^ "Christopher Eipper (1813–1894)". Street Signs – And What They Mean. Pelican Waters Shire Council. Archived from the original on 18 November 2007. Retrieved 20 December 2007.

- ^ "Frank Henry Vogler | German Immigrant | Johann Cesar 1863". mcnamarafamily.id.au. Archived from the original on 27 February 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "German Settlement in Queensland in the 19th Century". Germanaustralia.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "Fortitude Valley – suburb in City of Brisbane (entry 49857)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ de Strzelecki, Paul Edmond (1845). Physical Description of New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land: Accompanied by a Geological Map, Sections, and Diagrams. London, United Kingdom: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

- ^ "The Queensland Proclamation" (PDF). Queensland Government Archives. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ Evans, Raymond (2007). A History of Queensland. Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780521545396.

- ^ Shrimpton, James (6 October 2007). "Australia: The tale of Baron Lamington and an improvised cake". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ "The Black War in Queensland – Outrages in Brisbane district" (PDF). UQ. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ Raymond Constant Kerkhove (2014). "Tribal alliances with broader agendas – Terror (psychological warfare)". Cosmopolitan Civil Societies Journal. 6 (3). doi:10.5130/ccs.v6i3.4218.

- ^ "Local Intelligence". The Moreton Bay Courier. Vol. I, no. 35. Queensland, Australia. 13 February 1847. p. 2. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Domestic Intelligence". The Moreton Bay Courier. Vol. IV, no. 182. Queensland, Australia. 8 December 1849. p. 2. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The Great Fire of Brisbane, 1864". State Library of Queensland. 11 September 2008. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "150th anniversary – Brisbane's Bread or Blood Riot". SLQ. 4 October 2016. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ "City Botanical Gardens – Brisbane Visitors Guide". Brisbane Australia. Archived from the original on 13 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "Botanic Gardens, Brisbane". New South Wales Government Gazette. No. 32. New South Wales, Australia. 23 February 1855. p. 483. Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Fagg, Murray (26 May 2009). "City Botanic Gardens (Brisbane)". Australian National Botanic Gardens. Council of Heads of Australian Botanic Gardens. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ^ Jessica Hinchliffe (1 November 2017). "Why Brisbane, not Grafton, is the original jacaranda capital of Australia". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ King, Stuart (2010). "Colony and Climate: Positioning Public Architecture in Queensland 1859–1909". ABE Journal. Open Edition Journals. 2 (2). doi:10.4000/abe.402.

- ^ Evans, Raymond. "Anti Chinese Riot: Lower Albert Street" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ "Terrible disaster". The Brisbane Courier. 14 February 1896. p. 5. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022 – via Trove.

- ^ قالب:Cite QHR

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, pg. 165.

- ^ قالب:Cite Australian Dictionary of Biography

- ^ "Brisbane". ANZAC Day Commemoration Committee (Qld) Incorporated. 1998. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 28 December 2007.

- ^ "Raid on Parliament". Trove. 23 August 1939. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ Peter Dunn (2 March 2005). "Hirings Section". Australia @ War. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ "QM Supply in the Pacific during WWII". Quartermaster Professional Bulletin. Spring 1999. Archived from the original on 21 February 2004. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ Dan Nancarrow (5 July 2012). "Theatre play explores Brisbane's boundaries". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ E.J. Tait (14 August 1942). "Unspeakable orgy in Brisbane". Trove. Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ "A History of Australian Capital City Centres Since 1945". openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au. Australian National University. October 1997. Archived from the original on 20 May 2025. Retrieved 31 May 2025.

- ^ Peter Dunn (27 August 2005). "The Battle of Brisbane – 26 & 27 November 1942". Australia @ War. Archived from the original on 10 January 2008. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ Brisbane's last in but best-dressed, Brooke Falvey, City news, 11 July 2008. Archived 15 ديسمبر 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Swanwick, Tristan (12 December 2010). "Filmmakers on trail of Brisbane Bard". The Courier-Mail. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "She picked me up at a dance one night", Joan and Bill Bentson, Queensland Government. Archived 18 يونيو 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Robinson, Shirleene (3 May 2019). "Issues that swung elections: the dramatic and inglorious fall of Joh Bjelke-Petersen". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 16 February 2023. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Bryce, Alex. "We Would Live in Peace and Tranquility and No One Would Know Anything", Australian Academic and Research Libraries 31.3 (2000): 65–81.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Ross. "A History of Queensland, from 1915 to the 1980s", University of Queensland Press, 1985. Print.

- ^ Keim, Stephen. "The State of (Civil Liberties in Queensland): New Broom – Same Dirt." Legal Service Bulletin 13.1(1988):10–11. Web.

- ^ Plunkett, Mark and Ralph Summy 'Civil Liberties in Queensland: A nonviolent political campaign.' "Social Alternatives" Vol 1 no. 6/7, 1980 p 73-90

- ^ Bjelke-Petersen, in Patience The Bjelke-Petersen premiership 1968–1983 : issues in public policy. Longman Cheshire: Melbourne. 1985.

- ^ Summy, Ralph. Bruce Dickson and Mark Plunkett. "Phantom Civil Liberties Marches – Queensland University 1978–79" Archived 5 أكتوبر 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Plunkett, Geoff (5 May 2018). The Whiskey Au Go Go massacre: murder, arson and the crime of the century. Newport, NSW: Blue Sky Publishing. ISBN 9781925675443. OCLC 1041112112.

- ^ "ACGA Past Games 1982". Commonwealth Games Australia. Archived from the original on 17 September 2007. Retrieved 28 December 2007.

- ^ Rebecca Bell. "Expo 88 / Brisbane". OZ Culture. Archived from the original on 28 January 1999. Retrieved 28 December 2007.

- ^ "Brisbane City Council. Urban Renewal Brisbane – 20 Years Celebration Magazine. p 14" (PDF). Brisbane.qld.gov.au. Retrieved 12 January 2018.[dead link]

- ^ Berry, Petrina (13 January 2011). "Brisbane braces for flood peak as Queensland's flood crisis continues". The Courier-Mail. Archived from the original on 16 August 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ "Before and after photos of the floods in Brisbane". Abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ "Cox Rayner + Arup complete worlds largest tensegrity bridge in Brisbane". World Architecture News. 13 October 2009. Archived from the original on 17 October 2009. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

- ^ "Why Brisbane's Perceived 'Apartment Boom' Is Actually Here to Stay". Brisbane Development. 10 March 2016. Archived from the original on 23 June 2025. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ Tilley, Elizabeth (26 December 2022). "The high life: 10k apartments bound for inner Brisbane in 2023". Real Estate. Archived from the original on 23 June 2025. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةauto2 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةauto3 - ^ "Flood-proof road destroyed in deluge". ABC News. 12 October 2010. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014.

- ^ "Brisbane's FloodSmart Future Strategy". 9 May 2019. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Gregory, Helen (2007). Brisbane Then and Now. Wingfield, South Australia: Salamander Books. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-74173-011-1.

- ^ "Brisbane Tuff". Windsor and Districts Historical Society. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ "Get out and explore Brisbane's top jacaranda trees hotspots". Visit Brisbane. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ أ ب Brisbane City Council. "Symbols used by Council". Brisbane City Council. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ Brisbane City Council. "Symbols used by Council". Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- ^ Brisbane City Council. "Koala facts". Brisbane City Council. Archived from the original on 26 June 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ "Climate: Brisbane – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ Tapper, Andrew; Tapper, Nigel (2006). "Sub-Synoptic-Scale Processes and Phenomena". In Gray, Kathleen (ed.). The weather and climate of Australia and New Zealand (Second ed.). Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-19-558466-0.

- ^ Linacre, Edward; Geerts, Bart (1997). "Southern Climates". Climates and Weather Explained. London: Routledge. p. 379. ISBN 0-415-12519-7. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "Climate statistics for Australian stations – Brisbane". Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت قالب:BoM Aust stats

- ^ "Daily Maximum Temperature – 040913 – Bureau of Meteorology". Bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Daniel Sankey and Tony Moore (19 July 2007). "Coldest day on record for Brisbane". Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2008.

- ^ أ ب ت قالب:BoM Aust stats

- ^ قالب:BoM Aust stats

- ^ Unknown (24 August 2009). "Hot August day as Records Fall". Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on 27 August 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ قالب:BoM Aust stats

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone Risks" (PDF). Geoscience Australia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ "Brisbane Climate Guide". Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ^ Bureau of Meteorology. "Brisbane". Archived from the original on 17 January 2025. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (25 October 2007). "Community Profile Series : Brisbane (Major Statistical Region)". 2006 Census of Population and Housing. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

وصلات خارجية

- BRISbites: Suburban Sites (History)

- Our Brisbane - Council administered information site

- City of Brisbane

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأسترالية-language sources (en-au)

- CS1 errors: URL–wikilink conflict

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Articles with dead external links from October 2022

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing غالية اسكتلندية-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية القديمة (ح. 450-1100)-language text

- Articles containing Yagara-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Wikipedia articles needing factual verification from September 2020

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2020

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2024

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2022

- Articles with unsourced quotes

- Pages with empty portal template

- Host cities of the Commonwealth Games

- بريزبين

- Australian capital cities

- Coastal cities in Australia

- Towns and cities with limited zero-fare transport

- مدن أستراليا