نيوساوث ويلز

نيوساوث ويلز | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s): The First State The Premier State | |

| Motto: Orta Recens Quam Pura Nites (Newly Risen, How Brightly You Shine) | |

| صفة المواطن | New South Welshman[1][2] |

• Water (%) | 1.09 |

| Time zone | UTC+10 (AEST) UTC+11 (AEDT) UTC+9:30 (ACST) (Broken Hill) UTC+10:30 (ACDT) (Broken Hill) UTC+10:30 (LHST) (Lord Howe Island) UTC+11:00 (LHDT) (Lord Howe Island) |

| Website | www.nsw.gov.au |

| Coordinates[3] Emblems[4] | |

نيوساوث ويلز (بالإنجليزية: New South Wales) هي أقدم ولايات أستراليا وأكثرها اكتظاظاً بالسكان، حيث بلغ عدد سكانها 6764600 نسمة في نهاية مارس عام 2005. تقع جنوب شرق أستراليا، شمال ولاية فكتوريا، وجنوب ولاية كوينزلاند. تأسست عام 1788.

تغطي نيوساوث ويلز مساحة قدرها 809444 كم2، وهي خامس أكبر ولاية أسترالية. عاصمة الولاية هي مدينة سيدني، أقدم وأكبر مدن أستراليا، والتي تعتبر مركزاً اقتصادياً هاماً في البلاد.

تاريخ

أبورجيني (السكان الأصليون)

The original inhabitants of New South Wales were the Aboriginal tribes who arrived in Australia about 40,000 to 60,000 years ago. Before European settlement there were an estimated 250,000 Aboriginal people in the region.[9]

The Wodi wodi people, who spoke a variant of the Dharawal language, are the original custodians of an area south of Sydney which was approximately bounded by modern Campbelltown, Shoalhaven River and Moss Vale and included the Illawarra.[10]

The Bundjalung people are the original custodians of parts of the northern coastal areas.[citation needed]

There are other Aboriginal peoples whose traditional lands are within what is now New South Wales, including the Wiradjuri, Gamilaray, Yuin, Ngarigo, Gweagal, and Ngiyampaa peoples.

1788—الاستيطان البريطاني

في عام 1770، اكتشف القبطان جيمس كوك الساحل الشرقي لهولندا الجديدة (التي أخذت اسمها من هولندا)، والتي أصبحت الآن نيوساوث ويلز، التي أخذت هي الأخرى اسمها من جنوب ويلز. وفي عام 1788، أسس القبطان آرثر فيليب مستعمرة بريطانية جزائية في ميناء جاكسون، والتي هي الآن مدينة سيدني.

In 1770, James Cook charted the unmapped eastern coast of the continent of New Holland, now Australia, and claimed the entire coastline that he had just explored as British territory. Contrary to his instructions, Cook did not gain the consent of the Aboriginal inhabitants.[11][12] Cook originally named the land New Wales, but on his return voyage to Britain he settled on the name New South Wales.[13][أ]

In January 1788 Arthur Phillip arrived in Botany Bay with the First Fleet of 11 vessels, which carried over a thousand settlers, including 736 convicts.[16] A few days after arrival at Botany Bay, the fleet moved to the more suitable Port Jackson, where Phillip established a settlement at the place he named Sydney Cove (in honour of the Secretary of State, Lord Sydney) on 26 January 1788.[17] This date later became Australia's national day, Australia Day. Governor Phillip formally proclaimed the colony on 7 February 1788 at Sydney. Phillip, as Governor of New South Wales, exercised nominal authority over all of Australia east of the 135th meridian east between the latitudes of 10°37'S and 43°39'S, and "all the islands adjacent in the Pacific Ocean". The area included modern New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria, Tasmania.[18] He remained as governor until 1792.[19]

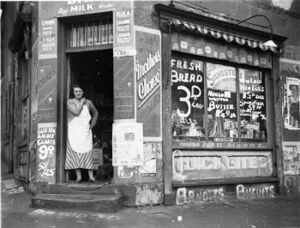

The settlement was initially planned to be a self-sufficient penal colony based on subsistence agriculture. Trade and shipbuilding were banned to keep the convicts isolated. However, after the departure of Governor Phillip, the colony's military officers began acquiring land and importing consumer goods obtained from visiting ships. Former convicts also farmed land granted to them and engaged in trade. Farms spread to the more fertile lands surrounding Paramatta, Windsor and Camden, and by 1803 the colony was self-sufficient in grain. Boat building was developed to make travel easier and exploit the marine resources of the coastal settlements. Sealing and whaling became important industries.[20]

In March 1804, Irish convicts led around 300 rebels in the Castle Hill Rebellion, an attempt to march on Sydney, commandeer a ship, and sail to freedom.[21] Poorly armed, and with their leader Philip Cunningham captured, about 100 troops and volunteers routed the main body of insurgents at Rouse Hill. At least 39 convicts were killed in the uprising and subsequent executions.[22][23]

Lachlan Macquarie (governor 1810–1821) commissioned the construction of roads, wharves, churches and public buildings, sent explorers out from Sydney, and employed a planner to design the street layout of Sydney.[24] A road across the Blue Mountains was completed in 1815, opening the way for large scale farming and grazing in the lightly wooded pastures west of the Great Dividing Range.[25]

In 1825 Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania) became a separate colony and the western border of New South Wales was extended to the 129th meridian east (now the West Australian border).[26]

New South Wales established a military outpost on King George Sound in Western Australia in 1826 which was later transferred to the Swan River colony.[27][28][29]

In 1839, the UK decided to formally annex at least part of New Zealand to New South Wales.[30] It was administered as a dependency until becoming the separate Colony of New Zealand on 3 May 1841.[31][32]

From the 1820s, squatters increasingly established unauthorised cattle and sheep runs beyond the official limits of the settled colony. In 1836, an annual licence was introduced in an attempt to control the pastoral industry, but booming wool prices and the high cost of land in the settled areas encouraged further squatting. The expansion of the pastoral industry led to violent episodes of conflict between settlers and traditional Aboriginal landowners, such as the Myall Creek massacre of 1838.[33] By 1844 wool accounted for half of the colony's exports and by 1850 most of the eastern third of New South Wales was controlled by fewer than 2,000 pastoralists.[34]

The transportation of convicts to New South Wales ended in 1840, and in 1842 a Legislative Council was introduced, with two-thirds of its members elected and one-third appointed by the governor. Former convicts were granted the vote, but a property qualification meant that only one in five adult males were enfranchised.[35]

By 1850 the settler population of New South Wales had grown to 180,000, not including the 70,000 living in the area which became the separate colony of Victoria in 1851.[36]

1850s to 1890s

In 1856 New South Wales achieved responsible government with the introduction of a bicameral parliament comprising a directly elected Legislative Assembly and a nominated Legislative Council. William Charles Wentworth was prominent in this process, but his proposal for a hereditary upper house was widely ridiculed and subsequently dropped.[37][38]

The property qualification for voters had been reduced in 1851, and by 1856 95 per cent of adult males in Sydney, and 55 per cent in the colony as a whole, were eligible to vote. Full adult male suffrage was introduced in 1858. In 1859 Queensland became a separate colony.[39]

In 1861 the NSW parliament legislated land reforms intended to encourage family farms and mixed farming and grazing ventures. The amount of land under cultivation subsequently increased from 246,000 acres in 1861 to 800,000 acres in the 1880s. Wool production also continued to grow, and by the 1880s New South Wales produced almost half of Australia's wool. Coal had been discovered in the early years of settlement and gold in 1851, and by the 1890s wool, gold and coal were the main exports of the colony.[40]

The NSW economy also became more diversified. From the 1860s, New South Wales had more people employed in manufacturing than any other Australian colony. The NSW government also invested strongly in infrastructure such as railways, telegraph, roads, ports, water and sewerage. By 1889 it was possible to travel by train from Brisbane to Adelaide via Sydney and Melbourne. The extension of the rail network inland also encouraged regional industries and the development of the wheat belt.[41]

In the 1880s trade unions grew and were extended to lower skilled workers. In 1890 a strike in the shipping industry spread to wharves, railways, mines, and shearing sheds. The defeat of the strike was one of the factors leading the Trades and Labor Council to form a political party. The Labor Electoral League won a quarter of seats in the NSW elections of 1891 and held the balance of power between the Free Trade Party and the Protectionist Party.[42][43]

The suffragette movement was developing at this time. The Womanhood Suffrage League of New South Wales was founded in 1891.[44]

1901—Federation of Australia

A Federal Council of Australasia was formed in 1885 but New South Wales declined to join. A major obstacle to the federation of the Australian colonies was the protectionist policies of Victoria which conflicted with the free trade policies dominant in New South Wales. Nevertheless, the NSW premier Henry Parkes was a strong advocate of federation and his Tenterfield Oration in 1889 was pivotal in gathering support for the cause. Parkes also struck a deal with Edmund Barton, leader of the NSW Protectionist Party, whereby they would work together for federation and leave the question of a protective tariff for a future Australian government to decide.[45]

In early 1893 the first citizens' Federation League was established in the Riverina region of New South Wales and many other leagues were soon formed in the colony. The leagues organised a conference in Corowa in July 1893 which developed a plan for federation. The new NSW premier, George Reid, endorsed the "Corowa plan" and in 1895 convinced the majority of other premiers to adopt it. A constitutional convention held sessions in 1897 and 1898 which resulted in a proposed constitution for a Commonwealth of federated states. However, a referendum on the constitution failed to gain the required majority in New South Wales after that colony's Labor party campaigned against it and premier Reid gave it such qualified support that he earned the nickname "yes-no Reid".[46]

The premiers of the other colonies agreed to a number of concessions to New South Wales (particularly that the future Commonwealth capital would be located in NSW), and in 1899 further referendums were held in all the colonies except Western Australia. All resulted in yes votes, with the yes vote in New South Wales meeting the required majority. The Imperial Parliament passed the necessary enabling legislation in 1900 and Western Australia subsequently voted to join the new federation. The Commonwealth of Australia was inaugurated on 1 January 1901, and Barton was sworn in as Australia's first prime minister.[47]

1901 to 1945

The first post-federation NSW governments were Progressive or Liberal Reform and implemented a range of social reforms with Labor support. Women won the right to vote in NSW elections in 1902, but were ineligible to stand for parliament until 1918. Labor increased its parliamentary representation in every election from 1904 before coming to power in 1910 with a majority of one seat.[48][49]

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 saw more NSW volunteers for service than the federal authorities could handle, leading to unrest in camps as recruits waited for transfer overseas. In 1916 NSW premier William Holman and a number of his supporters were expelled from the Labor party over their support for military conscription. Holman subsequently formed a Nationalist government which remained in power until 1920. Despite a huge victory for Holman's pro-conscription Nationalists in the elections of March 1917, a second referendum on conscription held in December that year was defeated in New South Wales and nationally.[50]

Following the war, NSW governments embarked on large public works programs including road building, the extension and electrification of the rail network and the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. The works were largely funded by loans from London, leading to a debt crisis after the onset of the Great Depression in 1929. New South Wales was hit harder by the depression than other states, and by 1932 one third of union members in the state were unemployed, compared with 20 per cent nationally.[51]

Labor won the November 1930 NSW elections and Jack Lang became premier for the second time. In 1931 Lang proposed a plan to deal with the depression which included a suspension of interest payments to British creditors, diverting the money to unemployment relief. The Commonwealth and state premiers rejected the plan and later that year Lang's supporters in the Commonwealth parliament brought down James Scullin's federal Labor government. The NSW Lang government subsequently defaulted on overseas interest payments and was dismissed from office in May 1932 by the governor, Sir Phillip Game.[52][53]

The following elections were won comfortably by the United Australia Party in coalition with the Country Party. Bertram Stevens became premier, remaining in office until 1939, when he was replaced by Alexander Mair.[54]

A contemporary study by sociologist A. P. Elkin found that the population of New South Wales responded to the outbreak of war in 1939 with pessimism and apathy. This changed with the threat of invasion by Japan, which entered the war in December 1941. In May 1942 three Japanese midget submarines entered Sydney harbour and sank a naval ship, killing 29 men aboard. The following month Sydney and Newcastle were shelled by Japanese warships. American troops began arriving in the state in large numbers. Manufacturing, steelmaking, shipbuilding and rail transport all grew with the war effort and unemployment virtually disappeared.[55]

A Labor government led by William McKell was elected in May 1941. The McKell government benefited from full employment, budget surpluses, and a co-operative relationship with John Curtin's federal Labor government. McKell became the first Labor leader to serve a full term and to be re-elected for a second. The Labor party was to govern New South Wales until 1965.[56]

فترة ما بعد الحرب

Post-war period

The Labor government introduced two weeks of annual paid leave for most NSW workers in 1944, and the 40-hour working week was implemented by 1947. The post-war economic boom brought near-full employment and rising living standards, and the government engaged in large spending programs on housing, dams, electricity generation and other infrastructure. In 1954 the government announced a plan for the construction of an opera house on Bennelong Point. The design competition was won by Jørn Utzon. Controversy over the cost of the Sydney Opera House and construction delays became a political issue and was a factor in the eventual defeat of Labor in 1965 by the conservative Liberal Party and Country Party coalition led by Robert Askin.[57]

The Askin government promoted private development, law and order issues and greater state support for non-government schools. However, Askin, a former bookmaker, became increasingly associated with illegal bookmaking, gambling and police corruption.[58]

In the late 1960s, a secessionist movement in the New England region of the state led to a 1967 referendum on the issue which was narrowly defeated. The new state would have consisted of much of northern NSW including Newcastle.[59]

Askin's resignation in 1975 was followed by a number of short-lived premierships by Liberal Party leaders. When a general election came in 1976, the ALP under Neville Wran came to power.[60] Wran was able to transform this narrow one seat victory into landslide wins (known as Wranslides) in 1978 and 1981.[61]

After winning a comfortable though reduced majority in 1984, Wran resigned as premier and left parliament. His replacement Barrie Unsworth struggled to emerge from Wran's shadow and lost a 1988 election against a resurgent Liberal Party led by Nick Greiner. The Greiner government embarked on an efficiency program involving public sector cost-cutting, the corporatisation of government agencies and the privatisation of some government services. An Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) was created.[62] Greiner called a snap election in 1991 which the Liberals were expected to win. However, the ALP polled extremely well and the Liberals lost their majority and needed the support of independents to retain power.

In 1992, Greiner was investigated by ICAC for possible corruption over the offer of a public service position to a former Liberal MP. Greiner resigned but was later cleared of corruption. His replacement as Liberal leader and Premier was John Fahey, whose government narrowly lost the 1995 election to the ALP under Bob Carr, who was to become the longest serving premier of the state.[63]

The Carr government (1995–2005) largely continued its predecessors' focus on the efficient delivery of government services such as health, education, transport and electricity. There was an increasing emphasis on public-private partnerships to deliver infrastructure such as freeways, tunnels and rail links. The Carr government gained popularity for its successful organisation of international events, especially the 2000 Sydney Olympics, but Carr himself was critical of the federal government over its high immigration intake, arguing that a disproportionate number of new migrants were settling in Sydney, putting undue pressure on state infrastructure.[64]

Carr unexpectedly resigned from office in 2005 and was replaced by Morris Iemma, who remained premier after being re-elected in the March 2007 state election, until he was replaced by Nathan Rees in September 2008.[65] Rees was subsequently replaced by Kristina Keneally in December 2009, who became the first female premier of New South Wales.[66] Keneally's government was defeated at the 2011 state election and Barry O'Farrell became Premier on 28 March. On 17 April 2014 O'Farrell stood down as Premier after misleading an ICAC investigation concerning a gift of a bottle of wine.[67] The Liberal Party then elected Treasurer Mike Baird as party leader and Premier. Baird resigned as Premier on 23 January 2017, and was replaced by Gladys Berejiklian.[68]

On 23 March 2019, Berejiklian led the Coalition to a third term in office. She maintained high personal approval ratings for her management of a bushfire crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. However, Berejiklian resigned as premier on 5 October 2021, following the opening of an ICAC investigation into her actions between 2012 and 2018. She was replaced by Dominic Perrottet.[69]

الجغرافيا

مدن ولاية نيوساوث ويلز الثلاثة الرئيسية من الشمال إلى الجنوب هم: نيوكاسل، وسيدني، ووولونغونغ، ويقع جميعها على الساحل. المدن الأخرى المعروفة في الولاية هي: ألبري، وبروكن هيل، ودوبو، وميناء ماكواري، وتاموورث، وآرمدال، وإنفيريل، وليسمور، ونورا، وغريفيث، وكوينبيان، وجيرابومبيرا، وليتون، وواغا واغا، وغوولبورن، وميناء كوفس.

تجاور نيوساوث ويلز كوينزلاند من الشمال، وجنوب أستراليا من الغرب، وولاية فكتوريا من الجنوب. يواجه ساحلها بحر تاسمان.

New South Wales is bordered on the north by Queensland, on the west by South Australia, on the south by Victoria and on the east by the Coral and Tasman Seas. The Australian Capital Territory and the Jervis Bay Territory form a separately administered entity that is bordered entirely by New South Wales. The state can be divided geographically into four areas. New South Wales's three largest cities, Sydney, Newcastle and Wollongong, lie near the centre of a narrow coastal strip extending from cool temperate areas on the far south coast to subtropical areas near the Queensland border. Gulaga National Park in the South Coast features the southernmost subtropical rainforest in the state.[70]

The Illawarra region is centred on the city of Wollongong, with the Shoalhaven, Eurobodalla and the Sapphire Coast to the south. The Central Coast lies between Sydney and Newcastle, with the Mid North Coast and Northern Rivers regions reaching northwards to the Queensland border. Tourism is important to the economies of coastal towns such as Coffs Harbour, Lismore, Nowra and Port Macquarie, but the region also produces seafood, beef, dairy, fruit, sugar cane and timber.[71][72]

The Great Dividing Range extends from Victoria in the south through New South Wales to Queensland, parallel to the narrow coastal plain. This area includes the Snowy Mountains, the Northern, Central and Southern Tablelands, the Southern Highlands and the South West Slopes. Whilst not particularly steep, many peaks of the range rise above 1،000 متر (3،281 ft), with the highest Mount Kosciuszko at 2،228 m (7،310 ft). Skiing in Australia began in this region at Kiandra around 1861. The relatively short ski season underwrites the tourist industry in the Snowy Mountains. Agriculture, particularly the wool industry, is important throughout the highlands. Major centres include Armidale, Bathurst, Bowral, Goulburn, Inverell, Orange, Queanbeyan and Tamworth.[citation needed]

There are numerous forests in New South Wales, with such tree species as Red Gum Eucalyptus and Crow Ash (Flindersia australis), being represented.[73] Forest floors have a diverse set of understory shrubs and fungi. One of the widespread fungi is Witch's Butter (Tremella mesenterica).[74]

The western slopes and plains fill a significant portion of the state's area and have a much sparser population than areas nearer the coast. Agriculture is central to the economy of the western slopes, particularly the Riverina region and Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area in the state's south-west. Regional cities such as Albury, Dubbo, Griffith and Wagga Wagga and towns such as Deniliquin, Leeton and Parkes exist primarily to service these agricultural regions. The western slopes descend slowly to the western plains that comprise almost two-thirds of the state and are largely arid or semi-arid. The mining town of Broken Hill is the largest centre in this area.[75]

One possible definition of the centre for New South Wales is located 33 كيلومتر (21 mi) west-north-west of Tottenham.[76]

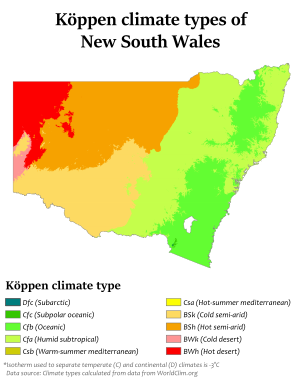

Climate

A little more than half of the state has an arid to semi arid climate, where the rainfall averages from 150 إلى 500 ميليمتر (5.9 إلى 19.7 in) a year throughout most of this climate zone. Summer temperatures can be very hot, while winter nights can be quite cold in this region. Rainfall varies throughout the state. The far north-west receives the least, less than 180 mm (7 in) annually, while the east receives between 700 و 1،400 mm (28 و 55 in) of rain.[77]

The climate along the flat, coastal plain east of the range varies from oceanic in the south to humid subtropical in the northern half of the state, right above Wollongong. Rainfall is highest in this area; however, it still varies from around 800 ميليمتر (31 in) to as high as 3،000 ميليمتر (120 in) in the wettest areas, for example Dorrigo. In the state's south, on the westward side of the Great Dividing Range, rainfall is heaviest in winter due to cold fronts which move across southern Australia, while in the north, around Lismore, rain is heaviest in summer from tropical systems and occasionally even cyclones.[77] During late winter, the coastal plain is relatively dry due to foehn winds that originate from the Great Dividing Range;[78] the mountain range block the moist, westerly cold fronts that arrive from the Southern Ocean, whereby providing generally clear conditions on the leeward side.[79][80]

The climate in the southern half of the state is generally warm to hot in summer and cool in the winter. The seasons are more defined in the southern half of the state, especially as one moves inland towards South West Slopes, Central West and the Riverina region. The climate in the northeast region of the state, or the North Coast, bordering Queensland, is hot and humid in the summer and mild in winter. The Northern Tablelands, which are also on the North coast, have relatively mild summers and cold winters, due to their high elevation on the Great Dividing Range.

Peaks along the Great Dividing Range vary from 500 متر (1،640 ft) to over 2،000 متر (6،562 ft) above sea level. Temperatures can be cool to cold in winter with frequent frosts and snowfall, and are rarely hot in summer due to the elevation. Lithgow has a climate typical of the range, as do the regional cities of Orange, Cooma, Oberon and Armidale. Such places fall within the subtropical highland (Cwb) variety. Rainfall is moderate in this area, ranging from 600 إلى 800 mm (24 إلى 31 in).

Snowfall is common in the higher parts of the range, sometimes occurring as far north as the Queensland border. On the highest peaks of the Snowy Mountains, the climate can be subpolar oceanic and even alpine on the higher peaks with very cold temperatures and heavy snow. The Blue Mountains, Southern Tablelands and Central Tablelands, which are situated on the Great Dividing Range, have mild to warm summers and cold winters, although not as severe as those in the Snowy Mountains.[77]

The highest maximum temperature recorded was 49.7 °C (121 °F) at Menindee in the west of the state on 10 January 1939. The lowest minimum temperature was −23 °C (−9 °F) at Charlotte Pass in the Snowy Mountains on 29 June 1994. This is also the lowest temperature recorded in the whole of Australia excluding the Antarctic Territory.[81]

| بيانات المناخ لـ New South Wales | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| القصوى القياسية °س (°ف) | 49.7 (121.5) |

48.5 (119.3) |

45.0 (113.0) |

40.0 (104.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.7 (89.1) |

37.8 (100.0) |

39.6 (103.3) |

43.9 (111.0) |

46.8 (116.2) |

48.9 (120.0) |

49.7 (121.5) |

| الصغرى القياسية °س (°ف) | −5.6 (21.9) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

−19.6 (−3.3) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−16.7 (1.9) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[82] | |||||||||||||

السكان

The estimated population of New South Wales at the end of December 2021 was 8,095,430 people, representing approximately 31.42% of nationwide population.[5]

In June 2017 Sydney was home to almost two-thirds (65.3%) of the NSW population.[83]

المدن والبلدات

| NSW rank | Statistical Area Level 2 | Population (30 June 2014)[84] |

10-year growth rate | Population density (people/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Greater Sydney | 4,940,628 | 15.7 | 397.4 |

| 2 | Newcastle and Lake Macquarie | 368,131 | 9.0 | 423.1 |

| 3 | Illawarra | 296,845 | 9.3 | 192.9 |

| 4 | Hunter Valley excluding Newcastle | 264,087 | 16.2 | 12.3 |

| 5 | Richmond Tweed | 242,116 | 8.9 | 23.6 |

| 6 | Capital region | 220,944 | 10.9 | 4.3 |

| 7 | Mid North Coast | 212,787 | 9.2 | 11.3 |

| 8 | Central West | 209,850 | 7.9 | 3.0 |

| 9 | New England and North West | 186,262 | 5.3 | 1.9 |

| 10 | Riverina | 158,144 | 4.7 | 2.8 |

| 11 | Southern Highlands and Shoalhaven | 146,388 | 10.4 | 21.8 |

| 12 | Coffs Harbour-Grafton | 136,418 | 7.6 | 10.3 |

| 13 | Far West and Orana | 119,742 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| 14 | Murray | 116,130 | 4.0 | 1.2 |

| New South Wales | 7,518,472 | 10.4 | 13.0 |

| NSW rank | Significant Urban Area | Population (30 June 2018/2021 Census)[85] |

Australia rank | 10-year growth rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sydney | 4,835,206 | 1 | 19.3 |

| – | Gold Coast – Tweed Heads | 654,073 | 6 | – |

| 2 | Newcastle – Maitland | 505,489 | 7 | 11.3 |

| 3 | Gosford (Central Coast) | 338,567 | 9 | 19.5 |

| 4 | Wollongong | 312,167 | 11 | 11.2 |

| – | Albury – Wodonga | 97,274 | 20 | 14.9 |

| 5 | Coffs Harbour | 71,822 | 25 | 11.8 |

| 6 | Wagga Wagga | 67,609 | 28 | 6.7 |

| 7 | Albury | 56,093 | 30 | 14.9 |

| 8 | Port Macquarie | 47,973 | 33 | 15.6 |

| 9 | Tamworth | 42,872 | 34 | 10.9 |

| 10 | Orange | 40,493 | 36 | 12.9 |

| 11 | Bowral – Mittagong | 39,887 | 37 | 13.5 |

| 12 | Dubbo | 38,392 | 39 | 12.2 |

| 13 | Nowra – Bomaderry | 37,420 | 42 | 14 |

| 14 | Bathurst | 33,801 | 43 | 15.0 |

| 15 | Lismore | 28,720 | 49 | −0.9 |

| 16 | Nelson Bay | 28,051 | 50 | 13.2 |

| 17 | Tweed Heads– Tweed Heads South | |||

| 18 | Taree | 26,448 | 55 | 2.3 |

| 19 | Ballina | 26,381 | 55 | 10.1 |

| 20 | Morisset – Cooranbong | 25,309 | 57 | 15.1 |

| 21 | Armidale | 24,504 | 58 | 7.0 |

| 22 | Goulburn | 23,835 | 59 | 12 |

| 23 | Forster – Tuncurry | 21,159 | 65 | 7.3 |

| 24 | Griffith | 20,251 | 66 | 11.5 |

| 25 | St Georges Basin – Sanctuary Point | 19,251 | 68 | 19.1 |

| 26 | Grafton | 19,078 | 69 | 3.5 |

| 27 | Camden Haven | 17,835 | 73 | 12.4 |

| 28 | Broken Hill | 17,734 | 74 | −9.5 |

| 29 | Batemans Bay | 16,485 | 78 | 4.4 |

| 30 | Singleton | 16,346 | 79 | −0.6 |

| 31 | Ulladulla | 16,213 | 81 | 11.8 |

| 32 | Kempsey | 15,309 | 84 | 5.8 |

| 33 | Lithgow | 12,973 | 93 | 4.8 |

| 34 | Mudgee | 12,410 | 95 | 21.5 |

| 35 | Muswellbrook | 12,364 | 96 | 5.0 |

| 36 | Parkes | 11,224 | 98 | 2.1 |

| New South Wales | 7,480,228 | N/A | 17.6 | |

Ancestry and immigration

| Birthplace[note 2] | Population |

|---|---|

| 5,277,497 | |

| 247,595 | |

| 231,385 | |

| 208,962 | |

| 118,527 | |

| 106,930 | |

| 97,995 | |

| 64,946 | |

| 63,293 | |

| 55,353 | |

| 53,046 | |

| 42,347 |

At the تعداد 2021, the most commonly nominated ancestries were:[note 4][87][86]

At the تعداد 2021, there were 2,794,666 people living in New South Wales that were born overseas, accounting for 34.6% of the population. Only 43.7% of the population had both parents born in Australia.[note 7][87]

3.4% of the population, or 278,043 people, identified as Indigenous Australians (Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders) in 2021.[note 8][87]

Language

According to the تعداد 2021, 29.5% of people in New South Wales speak a language other than English at home with Mandarin (3.4%), Arabic (2.8%), Cantonese (1.8%), Vietnamese (1.5%) and Hindi (1.0%) being the most popular.[87]

Religion

Religious Affiliations in New South Wales (2021 Census)

In the تعداد 2021, Christianity was the primary religious affiliation in New South Wales (NSW), comprising 47.6% of the population, mostly Roman Catholicism (22.4%) and Anglicanism (11.9%). This percentage has declined over time, while the number of people identifying with no religious affiliation has risen. In 2016, the Christian affiliation rate was 55.2%, and in 1971 it was 88.4%. About 33.2% of people in NSW reported having no religious affiliation in 2021.[87][89]

About 12.1% of the population in 2021 identified with a non-Christian religion, with Islam (4.3%), Hinduism (3.4%), and Buddhism (2.8%) being the most common.[90]

الاقتصاد

الزراعة

الثقافة

الولايات الشقيقة

New South Wales in recent history has pursued bilateral partnerships with other federated states/provinces and metropolises through establishing a network of sister state relationships. The state currently has 7 sister states:[91]

- Guangdong, China (since 1979)

- Tokyo, Japan (since 1984)

- Ehime, Japan (since 1999)[92]

- North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany (since 1989)

- Seoul, South Korea (since 1991)

- Jakarta, Indonesia (since 1994)

- California, United States (since 1997)

انظر أيضاً

- قالب:Books-inline

- Outline of Australia

- Index of Australia-related articles

- Geology of New South Wales

- NSW Volunteer of the Year

- Postage stamps and postal history of New South Wales

- Selection (Australian history)

- Squattocracy

- Territorial evolution of Australia

ملاحظات

المراجع

- ^ "The origin of the term 'cockroach'". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 13 June 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ Jopson, Debra (23 May 2012). "Origin of the species: what a state we're in". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ قالب:NSW GNR

- ^ "NSW State Flag & Emblems". NSW Government. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب "Australian Demographic Statistics, Dec 2018". 20 June 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2019. Estimated Resident Population – 1 December 2018

- ^ "5220.0 – Australian National Accounts: State Accounts, 2017–18". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 16 November 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ "Floral Emblem of New South Wales". www.anbg.gov.auhi. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ^ "New South Wales". Parliament@Work. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ "Aboriginal settlement". About NSW. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ History of Aboriginal People of the Illawarra 1770 to 1970. Department of Environment and Conservation, NSW. 2005. p. 8.

- ^ Beagleole, J. C. (1974). The Life of Captain James Cook. London: Adam and Charles Black. p. 249. ISBN 9780713613827.

- ^ Blainey, Geoffrey (2020). Captain Cook's Epic Voyage: the Strange Quest for a Missing Continent. Melbourne and Sydney: Viking. pp. 238–239. ISBN 9781760895099.

- ^ Lipscombe, Trevor (December 2020). "The origins of the name New South Wales" (PDF). Placenames Australia. ISSN 1836-7976.

- ^ "Colony of Australia Bill 1887". Parliament of New South Wales. Retrieved 2024-07-25.

- ^ "Queensland's history—1800s". Queensland Government. 18 July 2018.

- ^ Karskens, Grace (2013). "The early colonial presence, 1788-1822". In Bashford, Alison; MacIntyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 91. ISBN 9781107011533.

- ^ Peter Hill (2008) p.141-150; Andrew Tink, Lord Sydney: The Life and Times of Tommy Townshend, Melbourne, Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2011.

- ^ "Governor Phillip's Instructions 25 April 1787 (UK)". Documenting a Democracy. National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 28 May 2006. Robert J. King, "Terra Australis, New Holland, and New South Wales: the Treaty of Tordesillas and Australia", The Globe, no.47, 1998, pp.35–55.

- ^ قالب:Cite Australian Dictionary of Biography

- ^ Karskens, Grace (2013). "The early colonial presence, 1788-1822". In Bashford, Alison; MacIntyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume I, Indigenous and colonial Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–114. ISBN 9781107011533.

- ^ Karskens (2009). pp. 29–297

- ^ "Castle Hill Rebellion". nma.gov.au (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 30 June 2021. Archived from the original on 10 August 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ Whitaker, Anne-Maree (2009). "Castle Hill convict rebellion 1804". Dictionary of Sydney. Archived from the original on 4 March 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ Karskens, Grace (2013). pp. 115–17

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). A History of New South Wales. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 118–19. ISBN 9780521833844.

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). p. 2

- ^ Battye, James Sykes (2005) [1924]. Western Australia: A History from its Discovery to the Inauguration of the Commonwealth. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 4362013. Retrieved 24 September 2021 – via Project Gutenberg of Australia.

- ^ Uren, Malcolm John Leggoe (1948). Land Looking West: The Story of Governor James Stirling in Western Australia. London: Oxford University Press. p. 24.

- ^ قالب:LandInfo WA

- ^ Ministry for Culture and Heritage (April 3, 2023). "Treaty timeline".

- ^ "Crown colony era – the Governor-General". NZHistory. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. March 2009. Archived from the original on 2 March 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Moon, Paul (2010). New Zealand Birth Certificates – 50 of New Zealand's Founding Documents. AUT Media. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-95829971-8.

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 19–21

- ^ Ford, Lisa; Roberts, David Andrew (2013). "Expansion, 1821–1850". The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume I.

- ^ Hirst, John (2016). Australian History in 7 Questions. Victoria: Black Inc. pp. 51–54. ISBN 9781922231703.

- ^ Ford, Lisa; Roberts, David Andrew (2013). p.138

- ^ Tink, Andrew (2009). William Charles Wentworth : Australia's greatest native son. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-192-5.

- ^ Hirst (2016). pp. 56–57

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 36, 55–57

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 57, 62, 64, 67

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 63, 76–77, 104

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 91–94

- ^ Hirst, John (2014). pp. 83–86

- ^ Godden, Judith, Pottie, Eliza (1837–1907), Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/pottie-eliza-13155, retrieved on 27 February 2021

- ^ Irving, Helen (2013). "Making the federal Commonwealth". The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume I. pp. 249–51.

- ^ Irving, Helen (2013). pp. 257–62

- ^ Irving, Helen (2013). pp. 263–65

- ^ Croucher, John S. (2020). A Concise History of New South Wales. NSW: Woodslane Press. p. 128. ISBN 9781925868395.

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 110. 118-19

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 122–25

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 132, 142

- ^ Bongiorno, Frank (2013). "Search for a solution, 1923–39". The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 2. pp. 79–81.

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 148–49

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 151, 157

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 157–58

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 161–62

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 156, 162, 168–75, 184–86

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 188, 193, 196–98

- ^ Rhodes, Campbell (27 October 2017). "Breaking up is hard to do: secession in Australia". Museum of Australian Democracy. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ "Parliament of New South Wales, Legislative Assembly election: Election of 1 May 1976". Australian Politics and Elections Archive 1856–2018. University of Western Australia. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ Bramston, Troy (2006). The Wran era. Leichhardt, N.S.W.: Federation Press. p. 31. ISBN 1-86287-600-2. OCLC 225332582.

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 231–34

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 234–238

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 238, 241–46

- ^ Benson, Simon; Hildebrand, Joe (5 September 2008). "Nathan Rees new NSW premier after Morris Iemma quits". Courier Mail. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ "Keneally sworn in as state's first female premier". Herald Sun. Australia. 4 December 2009. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ^ "NSW Premier Barry O'Farrell to resign over 'massive memory fail' at ICAC". ABC news. 17 April 2014. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ Croucher, John S. (2020).p. 130

- ^ Gerathy, Sarah; Kennedy, Jean (2 October 2021). "Gladys Berejiklian seemed invincible as Premier — now Superwoman is on ICAC's political scrap heap". ABC News. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Rainforest In Southern New South Wales by the University of New England. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ "Agriculture Industry Snapshot for Planning: Illawarra/Shoalhaven Region" (PDF). NSW Department of Primary Industries.

- ^ Dayal, E. (January 1980). "Agricultural adjustments in the Illawarra region". University of Wollongong.

- ^ Joseph Henry Maiden. 1908. The Forest Flora of New South Wales, v. 3, Australian Government Printing Office.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan, Witch's Butter: Tremella mesenterica, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed; N. Stromberg Archived 21 سبتمبر 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Australian Encyclopaedia, Vol. 7, Grolier Society.

- ^ "Geoscience Australia – Center of Australia, States and Territories". Archived from the original on 22 August 2008.

- ^ أ ب ت "Stormy Weather" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ Sharples, J.J. Mills, G.A., McRae, R.H.D., Weber, R.O. (2010) Elevated fire danger conditions associated with foehn-like winds in southeastern Australia. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology.

- ^ Rain Shadows Archived 22 سبتمبر 2021 at the Wayback Machine by Don White. Australian Weather News. Willy Weather. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ And the outlook for winter is ... wet Archived 25 يوليو 2021 at the Wayback Machine by Kate Doyle from The New Daily. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Rainfall and Temperature Records: National" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. Bureau of Meteorology. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ "3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2016–17: Main Features". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 24 April 2018. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018. Estimated resident population, 30 June 2017.

- ^ "3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2013–14". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 31 March 2015. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ "3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2017–18". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 27 March 2019. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ أ ب "2021 New South Wales, Census Community Profile". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "2021 New South Wales, Census All persons QuickStats". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 12 September 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ "Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Australia (Feature Article)". Australian Bureau of Statistics. January 1995. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ "Faith and Religion for International Students in NSW". Study NSW (in الإنجليزية). 2023-07-21. Retrieved 2024-11-01.

- ^ "Faith and Religion for International Students in NSW". Study NSW (in الإنجليزية). 2023-07-21. Retrieved 2024-11-01.

- ^ "Building international relationships". NSW Government. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "International exchange activated with globalization". Ehime Prefecture. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

وصلات خارجية

- Official NSW Website

- NSW Parliament

- Official NSW Tourism Website

- New South Wales at the Open Directory Project

Geographic data related to نيوساوث ويلز at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to نيوساوث ويلز at OpenStreetMap

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "note"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="note"/>

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using infobox political division with unknown parameters

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2024

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2024

- Pages with empty portal template

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- New South Wales

- دول وأقاليم تأسست في 1788

- 1788 establishments in Australia

- ولايات وأقاليم أستراليا