ردوود، المنتزهات الوطنية والولائية

| منتزهات ردوودز الولائية والوطنية Redwood National and State Parks | |

|---|---|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

الضباب في الغابة. | |

| الموقع | مقاطعة همبولت ودل نورتى، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة |

| أقرب مدينة | مدينة كرسنت |

| الإحداثيات | 41°18′N 124°00′W / 41.3°N 124°W |

| المساحة | 112،618 acre (45،575 ha)[1] |

| تأسست | 1 يناير 1968 |

| الزوار | 380,167 (in 2011)[2] |

| الهيئة الحاكمة | إدارة مشتركة بين مصلحة المنتزهات الوطنية وادارة كاليفورنيا للمنتزهات والترفيه |

| الاسم الرسمي | منتزه ردوودز الوطني |

| النوع | طبيعي |

| المعيار | vii, ix |

| التوصيف | 1980 (القسم الرابع) |

| الرقم المرجعي | 134 |

| الدولة | |

| المنطقة | أوروپا وأمريكا الشمالية |

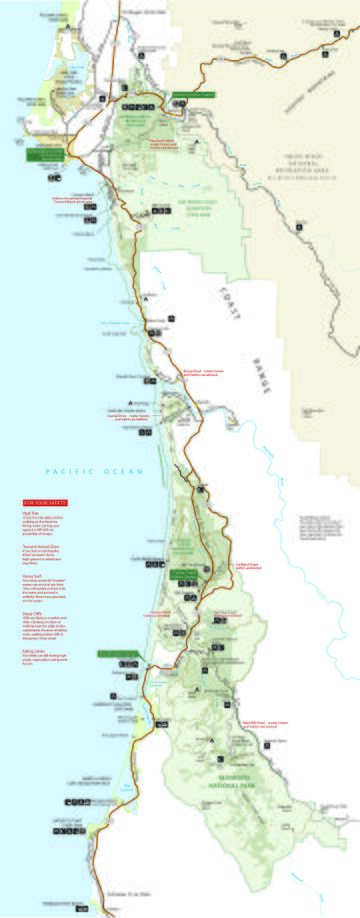

منتزهات ردوودز الوطني والولائية Redwood National and State Parks (RNSP)، يقع في الولايات المتحدة، على امتداد الساحل الشمالي لكاليفورنيا. ويتكون من منتزهات ردوودز الوطني (تأسس عام 1968)، منتزه ساحل دل نورتى، منتزه جديديا سميث، وبراري كريك (تعود إلى العشرينيات)، ويمتد على مساحة 133،000 acre (540 km2).[3] يقع المنتزه داخل مقاطعتي دل نورت وهمبولت، المنتزهات الأربعة معاً، تحمي 45% من ساحل ردوودز (Sequoia sempervirens)، غابات النمو القديم، بإجمالي مساحة 38،982 acre (157.75 km2) على الأقل. هذه الأشجار هي أطول وأضخم أنواع الأشجار على كوكب الأرض. بالإضافة إلى غابات ردوودز، تحفظ المنتزهات الحياة النباتية والحيوانية الأصلية الأخرى، سهوب البراري الشعبية، الموارد الثقافية، أجزاء من أنهار ومجاري مائية أخرى، وإمتداد 37 ميل (60 km) من الشريط الساحلي البكر..

Located in Del Norte and Humboldt counties, the four parks protect the endangered coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens)—the tallest, among the oldest, and one of the most massive tree species on Earth—which thrives in the humid temperate rainforest. The park region is highly seismically active and prone to tsunamis. The parks preserve 37 miles (60 km) of pristine coastline, indigenous flora, fauna, grassland prairie, cultural resources, waterways, as well as threatened animal species, such as the Chinook salmon, northern spotted owl, and Steller's sea lion.

Redwood forest originally covered more than two million acres (8,100 km2) of the California coast, and the region of today's parks largely remained wild until after 1850. The gold rush and attendant timber business unleashed a torrent of activity, adversely affecting the indigenous peoples of the area and supplying lumber to the West Coast. Decades of unrestricted clear-cut logging ensued, followed by ardent conservation efforts. In the 1920s, the Save the Redwoods League helped create Prairie Creek, Del Norte Coast, and Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Parks, among others. After lobbying from the league and the Sierra Club, Congress created Redwood National Park in 1968 and expanded it in 1978. In 1994, the National Park Service (NPS) and the California Department of Parks and Recreation combined Redwood National Park with the three abutting Redwoods State Parks into a single administrative unit. Modern RNSP management seeks to both protect and restore the coast redwood forests to their condition before 1850, including by controlled burning.

In recognition of the rare ecosystem and cultural history found in the parks, the United Nations designated them a World Heritage Site in 1980. Local tribes declared an Indigenous Marine Stewardship Area in 2023, protecting the parks region, the coastline, and coastal waters. Park admission is free except for special permits, and visitors may camp, hike, bike, and ride horseback along about 200 ميل (320 km) of park system trails.

التاريخ

Modern-day Native American nations such as the Yurok, Tolowa, Karuk, Chilula, and Wiyot have historical ties to the region,[4] which has had various indigenous occupants for millennia.[5] Describing "a diversity in an area that size that probably has never been equaled anywhere else in the world", historian David Stannard accounts for more than thirty native nations that lived in northwestern California.[6] Scholar Gail L. Jenner estimates that "at least fifteen" tribal groups inhabited the coastline.[7]

The Yurok, Chilula, and Tolowa were the most connected to the current parks' areas.[8] Based on an 1852 census, anthropologist Alfred Kroeber estimated that the Yurok population in that year was around 2,500.[4] Historian Ed Bearss described the Yurok as the most populous in the area, estimating that there were around 55 villages.[4] Until the 1860s, the Chilula lived in the middle region of the Redwood Creek valley in close company with the redwood trees.[9] They primarily settled along Redwood Creek between the coast and Minor Creek, California, and in summer they would range into and camp in the Bald Hills.[10] The Tolowa were located near the Smith River, and on lands that are now part of Jedediah Smith State Park, an area which 21st century excavation found has been inhabited for at least 8,500 years.[11]

Native Americans residing within the park areas relied on redwood trees as a construction material, and some featured the trees in their mythology, including the Chilula, who viewed the trees as gifts from a creator.[12] The tribes harvested coast redwoods and processed them into planks, using them as building material for boats, houses, and small villages.[13] To construct buildings, the planks would be erected side by side in a narrow trench, with the upper portions lashed with willow or hazel and held by notches cut into the supporting roof beams. Redwood boards were used to form a two- or three-pitch roof.[14]

وصول الأمريكان الأوروبيين

Historians believe that the first Europeans to visit land near what is now the parks were members of the Cabrillo expedition led by Bartolomé Ferrer.[15] In 1543, Ferrer's ship made landfall at Cape Mendocino and may have reached waters off Oregon as far north as the 43rd parallel.[15] Hubert Howe Bancroft disagreed, believing that Ferrer's ship did not travel so far north.[15] Explorers including Francis Drake sailed past[16] the foggy, rocky coast, but generally did not set anchor until 1775, when Bruno de Heceta and Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra of Spain spent about ten days at the Yurok village of Tsurai south of the parks.[17] George Vancouver and Francisco de Eliza followed in 1793.[17] American fur trading ships under contract to Russians stopped at Tsurai during the early 19th century.[18]

Prior to Jedediah Smith in 1828, no other explorer of European descent is known to have explored the interior of the Northern California coastal region. Smith and nineteen companions left San Jose, California, and explored what are now called the Trinity, Smith, and Klamath rivers, passing through coast redwood forests and trading with Native American groups. They reached the coast near Requa, parts of which are within the parks' boundaries.[19]

The California Gold Rush of 1848 brought hundreds of thousands of Europeans and Americans to California,[20] and the discovery of gold along the Trinity River in 1850 brought many of them to the region of the parks. This quickly led to conflicts wherein native peoples were displaced, raped, enslaved, and massacred.[21] By 1895, only one third of the Yurok in one group of villages remained; by 1919, virtually all members of the Chilula tribe had either died or been assimilated into other tribes.[22] The Tolowa—whose numbers Bearss estimates at "well under 1,000" by the 1850s—had a population of about 120 in 1910,[23] having been nearly extinguished in massacres by settlers between 1853 and 1855.[24]

Redwood logging followed gold mining, and most mining companies became lumber interests.[25] Redwood has a straight grain, making planks easy to cut. Because redwood can defy the weather and does not warp, it became a valuable commodity.[26] Jenner says a good team of two men could saw through a redwood tree at about a foot per hour with a crosscut saw, their preferred tool until after World War II.[27] Because wheeled vehicles could not travel the landscape, teams of six or twelve oxen transported logs to logging roads.[28] Rivers or railroads took them to the region's lumber mills.[29] After the 1881 invention of the steam donkey and later its successor the bull donkey, the need to fell intervening trees so the donkeys could work spawned the practice called clearcutting.[30] Caterpillar tractors began to compete with manual labor in the late 1920s.[31]

جهود الحفاظ على المنتزه الولائي

After extensive logging, conservationists and concerned citizens began to seek ways to preserve remaining trees, which they saw being logged at an alarming rate.[32] Stumbling blocks slowed conservation: objections and some innovations came from the logging industry,[أ] construction of the Redwood Highway brought roadside attractions and more visitors to the trees,[35] Congress failed to act,[ب] and voracious demand for lumber came with the post-World War II construction boom.[ت]

Organizations formed to preserve the surviving trees:[37] concerned about the sequoia of Yosemite, John Muir cofounded the Sierra Club in 1892.[38] The Sempervirens Club was cofounded in 1900 by artist Andrew P. Hill who lobbied the media, and saw the oldest state park created along with the California state park system.[39] In 1916, politician William Kent purchased land outright and helped to write the bill founding the National Park Service (NPS). In 1918, John Merriam and other members of the Boone and Crockett Club[40] founded the Save the Redwoods League.[41] The league bought land and donated funds for land purchases. Historian Susan Schrepfer writes that, in a sixty-year-long marathon, the Save the Redwoods League and the Sierra Club were racing the logging companies for the old trees.[42]

At first, in 1919, with Congress showing interest but no appropriations, NPS director Stephen Mather formed the NPS system with private wealth[43]—he and his wealthy friends purchased parkland with their own money.[44] Balancing opponents and supporters, the Save the Redwoods League saw their compromise bill pass in 1923, allowing condemnation for park acquisition with state oversight.[45] In 1925, the league backed a bill that would authorize a statewide survey by a landscape architect and permit land acquisition and condemnation for parks. In 1926, the league retained Frederick Law Olmsted to make that survey.[46] The league added to their bill a proposed state constitutional amendment authorizing up to $6 million ($78.8 million في 2022) in bonds to equally match private donations for state land purchases.[47] After sustaining a governor's veto in 1925,[46] the league broadened its efforts to include the whole state, mounted a publicity campaign, and gained the support of the Los Angeles Times.[48] A new governor signed the parks bill into law in 1927, a bond issue was approved in the 1928 election.[48]

In 1927, Olmsted's survey was complete and concluded that only three percent of the state's redwoods could be preserved. He recommended four redwood areas for parks, including three areas that became Prairie Creek Redwoods, Del Norte Coast Redwoods, and Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Parks. A fourth became Humboldt Redwoods State Park, by far the largest of the individual Redwoods State Parks, but not in the Redwood National and State Parks system.[49] Now armed with matching funds after 1928, the league bought more land and added to these parks as conditions allowed.[50]

المنتزه الوطني

The NPS proposed a redwoods national park in 1938. The Save the Redwoods League opposed it, highlighting a division between preservationists who preferred unembellished nature and a segment of the park service who wished to provide recreation and playgrounds for the public.[51] Both the league and the Sierra Club wanted a redwoods national park by the 1960s, but the club and the league supported different locations.[52] The club and the league were antagonists during the 1960s,[53] often on opposite sides of national park arguments, until 1971 when the league backed a club position,[54] and the late 1970s when the league became a club member.[55]

The Sierra Club wanted the largest possible park and usually sought help from the federal government.[56] More cautious, the Save the Redwoods League tended to accommodate industry and support the state of California.[57] When the agency had no funds in 1963, the National Geographic Society funded an NPS survey of the redwoods.[58] In 1964, NPS released its ideas for three different sized redwood national parks.[59] In 1964, Congress passed the Land and Water Conservation Fund to allow federal funds to purchase parkland.[60]

Describing a reason for the club's success, Willard Pratt of the Arcata lumber company wrote, "The Sierra Club demonstrated a basic political fact of life: Opposition to particular preservation proposals usually is local while support is national. If decision making can be placed at the national level, preservation usually can win".[61]

Initially opposing the park in the 1960s, the Arcata, Georgia-Pacific, and Miller lumber businesses operated up to the boundaries being discussed.[62] In 1965, five logging companies formally objected to any redwood national park.[61] Schrepfer writes that the final bill divided the impact between the lumber companies, between California counties, and tried to appeal to both the league and the club. Schrepfer says that in large part, the bill was framed on the loggers' terms.[63] After intense lobbying of Congress, the bill creating Redwood National Park was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson in October 1968.[64]

The Save the Redwoods League donated parcels in 1974 and 1976.[65] The club found the Olmsted plan of delicately choosing sites was the wrong approach to defend against tractor clearcutting.[66] In 1977, the club said that only ridge-to-ridge land acquisition around a water channel could preserve a watershed and thus the trees.[67] Amidst both local support of environmentalists and opposition from local loggers and logging companies, 48،000 acre (190 km2) were added to Redwood National Park in an expansion signed by President Jimmy Carter in 1978.[68] The purchase included lands that had already been logged, and the NPS was charged with restoring the land and reducing soil erosion.[69] At hundreds of millions of dollars, it was the most expensive land purchase ever approved by Congress.[68] By 1979, the league had preserved 150،000 acre (610 km2), nearly twice the area that the federal government was able to save with park legislation.[66]

المزيد من العرفان

The United Nations designated the Redwood National and State Parks a World Heritage Site in 1980. The evaluation committee noted cooperative management and ongoing research in the parks by Cal Poly Humboldt University and other partners.[70] The parks are within the California Coast Ranges and their resources are considered irreplaceable.[71] In 1983, the parks were designated an International Biosphere Reserve.[72] In 2017, the US withdrew them along with more than a dozen other reserves from the World Network of Biosphere Reserves.[73]

In 2023, following the lead of First Nations in Canada and Aboriginal people in Australia, three federally recognized indigenous tribes—the Resighini Rancheria of the Yurok People, Tolowa Dee-ni' Nation, and Cher-Ae Heights Indian Community of the Trinidad Rancheria—announced that as sovereign governments they have protected the Yurok-Tolowa-Dee-ni' Indigenous Marine Stewardship Area.[74] The effort protected 700 ميل مربع (1،800 km2) of territorial ocean waters and coastline reaching from Oregon to just south of Trinidad, California,[74] and contributed to the California 30x30 plan to conserve 30 percent of the state's land and coastal water by 2030.[75] The tribes invited cooperation with US agencies and other indigenous nations.[76]

إدارة المتنزه

Redwood National Park is directly managed by the NPS from its office in Crescent City, California.[77] The three state parks are overseen by the California Department of Parks and Recreation.[78] The park management coordinates with tribal leaders, as the parks contain land and village sites belonging to groups including the Yurok and Tolowa.[10][21] NPS manages about 1،400 acre (5.7 km2) of federal park land and waters that lie within the Yurok Indian Reservation.[78]

Redwood National Park management oversees many other details aside from the redwoods and organic species that reside within the park boundaries. They regulate areas that are off limits to motor vehicles, boats, drones, horses, pets and even bicycles. In addition, park management establishes limitations on camping, campfires, food storage and backcountry use, as well as necessary permits.[79]

When it opened in 1969, Redwood National Park had six permanent employees.[80] As of 2023, the combined RNSP had 96 permanent and 52 temporary staff members.[72] Early park managers prioritized restoring existing structures, rehabilitating the watershed, and developing wildlife management plans.[81] Until 1980, managers assumed that the three state parks, which are contained within the boundaries of the national park, would be donated to the NPS.[78] The donation did not happen,[78] and NPS and the state signed a memorandum of understanding in 1994 governing joint management, and agreeing to the name "Redwood National and State Parks".[82] As of 2021, the combined RNSP had 1,185,000 annual visitors.[72]

الموارد الطبيعية

الحياة النباتية

الحياة الحيوانية

الفصائل الغازية

الجيولوجيا

Both coastline and the mountains of the California Coast Ranges can be found within park boundaries. The majority of the rocks in the parks are part of the Franciscan assemblage.[83] Assemblage metamorphic and sedimentary rocks of the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, along with marine and alluvial sedimentary deposits of the Tertiary and Quaternary periods, are underneath the Redwood Creek basin.[84] These sedimentary rocks are primarily sandstone, siltstone, and shale, with lesser amounts of chert, greenstone, and metamorphic rocks.[83]

The parks are located in the most seismically active area in the country. Frequent minor earthquakes in the park and offshore under the Pacific Ocean have resulted in shifting river channels, landslides, and erosion of seaside cliffs. The North American, Pacific, and Gorda Plates are tectonic plates that all meet at the Mendocino triple junction, about 100 ميل (160 km) southwest of the parks. During the 1990s, more than nine magnitude 6.0 earthquakes occurred along this fault zone.[85] More recently, a 6.4 magnitude quake in 2022 with a hypocenter off the coast caused two deaths. Visitors' centers closed but the parks remained open.[86] The area is the most tsunami-prone in the continental US, and visitors to the seacoast are told to seek higher ground immediately after any significant earthquake.[87] The parks' altitude ranges from below sea level up to 837 متر (2،746 ft) at Rodgers Peak.[70]

المناخ

The Redwood National and State Parks have a warm-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csb).[ث] They receive abundant rain during most of the year, with a peak in winter, a decrease in June and September, and two dry summer months (July and August).[89]

The parks are part of a temperate rainforest that runs along the western United States coast.[90] The nearby Pacific Ocean has major effects on the climate in the parks. Temperatures near the coast mostly remain between 40 and 60 degrees Fahrenheit (4–15 °C) all year.[91] Redwoods tend to grow in this area of steadily temperate climate, though most grow at least a mile or two (1.5–3 km) from the coast to avoid the saltier air, and they never grow more than 50 ميل (80 km) from it. In this humid coastal zone, the trees receive moisture from both heavy winter rains and persistent summer fog.[92] The presence and consistency of the summer fog is actually more important to overall health of the trees than the precipitation. This fact is borne out in precipitation totals of around 71 بوصات (180 cm) annually,[93] with healthy redwood forests throughout the areas of less precipitation because excessive needs for water are mitigated by the ever-present summer fog and the cooler temperatures it ensures. The rare snow falls mostly on the hills and mountains in and adjacent to the park.[94]

Parts of the parks are threatened by climate change. Increasing average temperatures have led to reduced water quality, affecting the fish and other fauna, and rising sea levels threaten to damage park structures near the coast. The redwoods benefit from higher carbon levels and are resilient against temperature changes.[95] Scientists fear climate change is likely to shift the range in which coast redwoods live to outside protected areas,[96] and many have done research on assisted migration.[97][ج]

| بيانات المناخ لـ منتزه ردوود الوطني والولائي؛ (جددياه سميث ردوودز، المتنزه الولائي؛ كاليفورنيا الشمالية | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| القصوى القياسية °ف (°س) | 75 (24) |

80 (27) |

81 (27) |

86 (30) |

91 (33) |

98 (37) |

89 (32) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

90 (32) |

78 (26) |

72 (22) |

98 (37) |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °ف (°س) | 53.4 (11.9) |

55.0 (12.8) |

56.0 (13.3) |

56.9 (13.8) |

60.7 (15.9) |

63.4 (17.4) |

65.0 (18.3) |

65.1 (18.4) |

65.2 (18.4) |

62.6 (17.0) |

56.6 (13.7) |

52.7 (11.5) |

59.4 (15.2) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °ف (°س) | 35.8 (2.1) |

36.5 (2.5) |

38.1 (3.4) |

39.9 (4.4) |

44.0 (6.7) |

47.6 (8.7) |

50.4 (10.2) |

50.8 (10.4) |

47.4 (8.6) |

42.9 (6.1) |

38.8 (3.8) |

35.5 (1.9) |

42.3 (5.7) |

| الصغرى القياسية °ف (°س) | 18 (−8) |

19 (−7) |

24 (−4) |

27 (−3) |

24 (−4) |

33 (1) |

34 (1) |

36 (2) |

24 (−4) |

28 (−2) |

22 (−6) |

16 (−9) |

16 (−9) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار inches (mm) | 12.18 (309) |

10.65 (271) |

10.31 (262) |

6.27 (159) |

3.94 (100) |

2.00 (51) |

0.37 (9.4) |

0.53 (13) |

1.21 (31) |

5.00 (127) |

11.42 (290) |

15.72 (399) |

79.60 (2٬022) |

| متوسط هطول الثلج inches (cm) | 0.4 (1.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

1.1 (2.8) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 17.6 | 15.7 | 17.1 | 14.0 | 9.0 | 5.3 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 3.8 | 7.7 | 16.3 | 17.4 | 127.8 |

| [citation needed] | |||||||||||||

ادارة الحريق

الترفيه

في السينما

انظر أيضاً

- ساحل دل نورتى ردوودز، المنتزه الولائي

- جديديا سميث ردوودز، المنتزه الولائي

- براري كريك ردوودز، المنتزه الولائي

الهوامش

- ^ "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- ^ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- ^ "National or State Park?" (PDF). Redwood National and State Parks Visitor Guide. National Park Service. June 24, 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ^ أ ب ت Bearss 1982, Section I. A. The Yurok.

- ^ Trask 2004, p. 8.

- ^ Stannard 1993.

- ^ Jenner 2016, p. 20.

- ^ Jenner 2016, pp. 20–21.

- ^ "The Chilula: Bald Hills People" (PDF). Park Newspaper (Visitor's Guide). National Park Service. 2002. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 11, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023 – via National Park Service History eLibrary.

- ^ أ ب Bearss 1982, Section I. C. The Chilula.

- ^ Tushingham 2013.

- ^ Jenner 2016, pp. VII–VIII, 35.

- ^ Castillo, Edward D. (1998). "Short Overview of California Indian History". California Native American Heritage Commission. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ^ Nabokov & Easton 1990, p. 290.

- ^ أ ب ت Bearss 1982, Section II. A. The Cabrillo–Ferrelo Expedition.

- ^ Bearss 1982, II. Coastal Exploration.

- ^ أ ب Heizer & Mills 2022, p. 1.

- ^ Heizer & Mills 2022, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Jenner 2016, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Jenner 2016, p. 44.

- ^ أ ب "American Indians". Area History. National Park Service. February 5, 2008. Archived from the original on December 2, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ^ "The Chilula". The Indians of the Redwoods. National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 27, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ Bearss 1982, Section I. B. The Tolowa.

- ^ Jenner 2016, p. 54.

- ^ Jenner 2016, p. 60.

- ^ Jenner 2016, pp. 61, 63.

- ^ Jenner 2016, pp. 60, 77.

- ^ Jenner 2016, p. 79.

- ^ Jenner 2016, p. 77.

- ^ Jenner 2016, pp. 80-81.

- ^ Jenner 2016, p. 81.

- ^ أ ب "Logging". Area History. National Park Service. Archived from the original on December 2, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ Jenner 2016, pp. 112–114.

- ^ Rosalsky, Greg (June 21, 2022). "The tale of a distressed American town on the doorstep of a natural paradise". NPR. Archived from the original on September 11, 2022. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- ^ Jenner 2016, Chapter 12: The Redwood Highway Cuts a Path Through the Trees.

- ^ Jenner 2016, p. 96.

- ^ Jenner 2016, p. 99.

- ^ Jenner 2016, p. 91.

- ^ Jenner 2016, pp. 92–95.

- ^ Jenner 2016, p. 127.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, pp. 4, 12.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, p. xiv.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, p. 231.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, pp. 18, 20.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, p. 29.

- ^ أ ب Schrepfer 1983, p. 31.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, p. 32.

- ^ أ ب Schrepfer 1983, p. 33.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, pp. 33–36.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, p. 36.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, p. 52, 60–61.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, p. 237.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, p. 214.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, pp. 79, 110–111, 124, 127, 204.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, pp. 111, 122.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, pp. 111, 230, 239.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, p. 117.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, pp. 118, 121.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, pp. 120–121.

- ^ أ ب Pratt (Arcata), Willard E. "Chronology: Establishment of the Redwood National Park" (PDF). NPS History. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 7, 2023. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, pp. 140–141, 150–151, 154.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, pp. 156, 162.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, p. 159.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, p. 212.

- ^ أ ب Schrepfer 1983, p. 239.

- ^ Schrepfer 1983, p. 203.

- ^ أ ب Schrepfer 1983, p. 226.

- ^ Crapsey 1997, pp. 59,62.

- ^ أ ب "Redwood National and State Parks". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on October 28, 2023. Retrieved October 29, 2023.

- ^ "Area History". National Park Service. November 23, 2022. Archived from the original on December 2, 2022. Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت "Park Facts". National Park Service. February 21, 2023. Archived from the original on January 30, 2024. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Casey; Greshko, Michael (June 14, 2017). "UN Announces 23 New Nature Reserves While U.S. Removes 17". National Geographic. Archived from the original on December 7, 2023. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ أ ب Hill, Jos; Hayden, Bobby (January 26, 2024). "Tribal Nations Designate First US Indigenous Marine Stewardship Area". Pew Charitable Trusts. Archived from the original on January 30, 2024. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ "What is 30x30?". State of California. Archived from the original on February 1, 2024. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ Kimbrough, Kim (January 29, 2024). "First ever U.S. Indigenous Marine Stewardship Area declared in California". Mongabay. Archived from the original on February 15, 2024. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ "Directions". National Park Service. January 7, 2023. Archived from the original on June 4, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Redwood National and State Parks: General Management Plan, General Plan (Summary)" (PDF). National Park Service and State of California. pp. 3, 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 17, 2023. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- ^ "Superintendent's Compendium". National Park Service. May 17, 2023. Archived from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ Jenner 2016, p. 167.

- ^ Jenner 2016, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Jenner 2016, p. 168.

- ^ أ ب "Redwood National & State Parks". International Union for Conservation of Nature and UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre. May 22, 2017. Archived from the original on January 15, 2024. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Cashman, Kelsey & Harden 1995, p. B1.

- ^ "Natural Features & Ecosystems". National Park Service. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- ^ Song, Sharon (December 20, 2022). "Redwood parks in Humboldt County remain open after Tuesday's 6.4 magnitude quake". KTVU TV. Fox Television Stations. Archived from the original on January 15, 2024. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Your Safety". National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 18, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- ^ "Table 2 Overview of the Köppen-Geiger climate classes including the defining criteria". Nature: Scientific Data (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on October 22, 2022. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ أ ب "CA Klamath". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 2017-05-25. Retrieved June 27, 2013. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "NCDC" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ Jenner 2016, p. 4.

- ^ "Weather". National Park Service. October 13, 2022. Archived from the original on December 28, 2008. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- ^ Jenner 2016, p. 6.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةNOWclimate - ^ Jenner 2016, p. 25.

- ^ "Redwoods and Climate Change". National Park Service. October 25, 2022. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- ^ Moukaddem, Karimeh (May 24, 2011). "iPhone app uses Google Earth to track climate change impact on redwoods". Mongabay. Archived from the original on December 30, 2023. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ Gilles, Nathan (December 28, 2023). "As tree species face decline, 'assisted migration' gains popularity in Pacific Northwest". Associated Press. Columbia Insight. Archived from the original on December 28, 2023. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ^ Dagley, Christa M.; Berrill, John-Pascal; Johnson, Forrest T.; Kerhoulas, Lucy P. (2017). Adaptation to climate change? Moving coast redwood seedlings northward and inland. US Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station: 219–227. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://research.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/55431. Retrieved on December 30, 2023. - ^ Douhovnikoff & Dodd 2011.

- ^ Winder, R.S.; Waring, V.R.; Jones, A.; Valance, A.; Eddy, I. (2022). Potential for Assisted Migration of Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) to Vancouver Island. Pacific Forestry Centre. ISBN 978-0-660-45861-8. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/publications?id=40819. Retrieved on December 30, 2023. - ^ "Klamath, California". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

المصادر

- National Park Service. "Redwood National and State Parks". Retrieved in 2006.

- Redwood National and State Parks. "Visitor Guide" (PDF). Retrieved in 2006.

- Redwood: A Guide to Redwood National and State Parks, California. Interior Dept., National Park Service, Division of Publications. 1997. ISBN 0-912627-61-1.

{{cite book}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

وصلات خارجية

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- IUCN Category V

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2011

- CS1 errors: missing name

- Official website different in Wikidata and Wikipedia

- ردوود، المتنزه الوطني والولائي

- منتزهات ولاية في كاليفورنيا

- منتزهات وطنية في كاليفورنيا

- غابات نمو قديم

- منتزهات في مقاطعة دل نورت، كاليفورنيا

- منتزهات في مقاطعة همبولت، كاليفورنيا

- مناطق محمية تأسست في 1968

- مواقع التراث العالمي في الولايات المتحدة